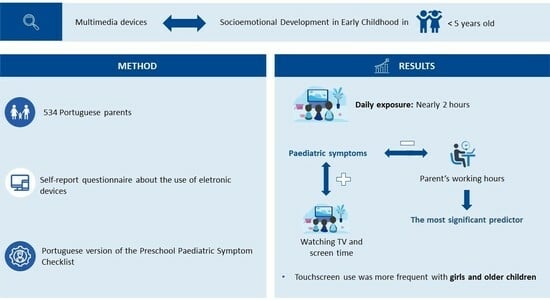

The Dark Side of Multimedia Devices: Negative Consequences for Socioemotional Development in Early Childhood

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

Use of Multimedia Devices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dardanou, M.; Unstad, T.; Brito, R.; Dias, P.; Fotakopoulou, O.; Sakata, Y.; O’Connor, J. Use of touchscreen technology by 0–3-year-old children: Parents’ practices and perspectives in Norway, Portugal and Japan. J. Early Child. Lit. 2020, 20, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, S.D.C.; Morais, R.L.D.S.; Santos, L.R.; Leite, H.R.; Nobre, J.N.P.; Santos, J.N. Children’s use of interactive media in early childhood-an epidemiological study. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2019, 38, e2018165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.; Choe, D.E. Mobile media and young children’s cognitive skills: A review. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 996–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesky, J.S.; Peacock-Chambers, E.; Zuckerman, B.; Silverstein, M. Use of mobile technology to calm upset children: Associations with social-emotional development. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; McArthur, B.A.; Anhorn, C.; Eirich, R.; Christakis, D.A. Associations between Screen Use and Child Language Skills: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobre, J.N.P.; Vinolas Prat, B.; Santos, J.N.; Santos, L.R.; Pereira, L.; Guedes, S.D.C.; Ribeiro, R.F.; Morais, R.L.D.S. Quality of interactive media use in early childhood and child development: A multicriteria analysis. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.) 2020, 96, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Alencar Rocha, M.F.; de Alencar Bezerra, R.E.; de Almeida Gomes, L.; Mendes, A.L.D.A.C.; de Lucena, A.B. Consequências do uso excessivo de telas para a saúde infantil: Uma revisão integrativa da literatura. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e39211427476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Jabarkheel, Z. Sugar-sweetened beverages and screen time: Partners in crime for adolescent obesity. J. Pediatr. 2019, 215, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Mohedano, F.; Pinto Hernández, F. Predicción del bienestar sobre el uso de pantallas inteligentes de los niños. Comunicar 2021, 29, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, A.S.; Heath, A.M.; Lawrence, J.; Galland, B.C.; Gray, A.R.; Taylor, B.J.; Sayers, R.; Taylor, R.W. Parenting style and family type, but not child temperament, are associated with television viewing time in children at two years of age. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisak, P.; Chiranuwat, S.; Pongtong, P.; Sakda Arj-Ong, V. ICT exposure in children younger than 2 years: Rates, associated factors, and health outcomes. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2018, 101, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, B.; Yeates, M.; Meyer, D.; Fleckhammer, L.; Kaufman, J. The effects of screen media content on young children’s executive functioning. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2018, 170, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria. Manual de Orientação: Saúde de Crianças e Adolescentes na Era Digital. Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria. Available online: https://nutritotal.com.br/pro/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Manual_orienta%C3%A7%C3%B5es_era_digital.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2023).

- Varadarajan, S.; Venguidesvarane, A.G.; Ramaswamy, K.N.; Rajamohan, M.; Krupa, M.; Christadoss, S.B.W. Prevalence of excessive screen time and its association with developmental delay in children aged <5 years: A population-based cross-sectional study in India. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254102. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, J.; Howard, S.J.; Vella, S.A.; Cliff, D.P. Longitudinal Associations of Electronic Application Use and Media Program Viewing with Cognitive and Psychosocial Development in Preschoolers. Acad. Pediatr. 2019, 19, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N.; Campbell, W.K. Decreases in psychological well-being among American adolescents after 2012 and links to screen time during the rise of smartphone technology. Emotion 2018, 18, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Liao, X.; Li, Y. Association of problematic smartphone use with poor sleep quality, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigan, S.; Browne, D.; Racine, N.; Mori, C.; Tough, S. Association between Screen Time and Children’s Performance on a Developmental Screening Test. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalická, V.; Wold Hygen, B.; Stenseng, F.; Kårstad, S.B.; Wichstrøm, L. Screen time and the development of emotion understanding from age 4 to age 8: A community study. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 37, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domoff, S.E.; Harrison, K.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Gentile, D.A.; Lumeng, J.C.; Miller, A.L. Development and validation of the problematic media use measure: A parent report measure of screen media “addiction” in children. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2019, 8, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.P.; Chen, K.L.; Chou, W.; Yuan, K.S.; Yen, S.Y.; Chen, Y.S.; Chow, J.C. Prolonged touch screen device usage is associated with emotional and behavioral problems, but not language delay, in toddlers. Infant Behav. Dev. 2020, 58, 101424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niiranen, J.; Kiviruusu, O.; Vornanen, R.; Saarenpää-Heikkilä, O.; Juulia Paavonen, E. High-dose electronic media use in five-year-olds and its association with their psychosocial symptoms: A cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e040848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Communications and Media. Media and Young Minds. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, B.; Nunes, C. Benefits and damages of the use of touchscreen devices for the health and development of children from 0 to 5 years of age–A systematic review. Psicol. Reflex. Crit. 2020, 33, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, R.; Ramos, A. Digital technology in a family environment: The case of children from 0 to 6 years old. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE), Lisbon, Portugal, 9–11 November 2017; pp. 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Ponte, C.; Simões, J.A.; Baptista, S.; Jorge, A.; Castro, T.S. Crescendo Entre Ecrãs: Usos de Meios Eletrónicos por Crianças (3–8 Anos); ERC–Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017; pp. 5–166. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.; Monaghana, P.; Westermanna, G. Investigating the association between children’s screen media exposure and vocabulary size in the UK. J. Child. Media 2018, 12, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikken, P.; Schols, M. How and Why Parents Guide the Media Use of Young Children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 3423–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, R.; Saez de Urabain, I.R.; Cheung, C.H.M.; Karmiloff-Smith, A.; Smith, T.J. Toddlers’ fine motor milestone achievement is associated with early touchscreen scrolling. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.; Gama, A.; Machado-Rodrigues, A.; Nogueira, H.; Silva, M.; Marques, V.; Padez, C. Social inequalities in traditional and emerging screen devices among Portuguese children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, B.; Nunes, C. O uso de dispositivos eletrónicos por crianças dos 0 aos 5 anos de idade. RMd 2021, 4, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabali, H.K.; Irigoyen, M.M.; Nunez-Davis, R.; Budacki, J.G.; Mohanty, S.H.; Leister, K.P.; Bonner, R.L. Exposure and use of mobile media devices by young children. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, I.; León, O.G. A guide for naming research studies in Psychology. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2007, 7, 847–862. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, B.; Nunes, C. Psychometric characteristics of the Portuguese version of the Preschool Pediatric Symptom Checklist for children aged 18 to 60 months. Rev. Psicol. 2021, 35, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, B.; Nunes, C. Translation and validation of the European Portuguese version of the Baby Pediatric Symptom Checklist. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2022, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, I.; Obara, T.; Ishikuro, M.; Murakami, K.; Ueno, F.; Noda, A.; Onuma, T.; Shinoda, G.; Nishimura, T.; Tsuchiya, K.J.; et al. Screen Time at Age 1 Year and Communication and Problem-Solving Developmental Delay at 2 and 4 Years. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 117, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hwang, G.J. Roles and research trends of touchscreen mobile devices in early childhood education: Review of journal publications from 2010 to 2019 based on the technology-enhanced learning model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 1683–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Guo, H.; Ma, D.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J.; Kim, H. The Association between 24h Movement Guidelines and Internalising and Externalising Behaviour Problems among Chinese Preschool Children. Children 2023, 10, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priftis, N.; Panagiotakos, D. Screen Time and Its Health Consequences in Children and Adolescents. Children 2023, 10, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofaro, D.G.D.; De Andrade, S.M.; Mesas, A.E.; Fernandes, R.A.; Farias Júnior, J.C. Higher screen time is associated with overweight, poor dietary habits and physical inactivity in Brazilian adolescents, mainly among girls. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassul, C.; Corish, C.A.; Kearney, J.M. Associations between home environment, children’s and parents’ characteristics and children’s TV screen time behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollborn, S.; Limburg, A.; Pace, J.; Fomby, P. Family Socioeconomic Status and Children’s Screen Time. J. Marriage Fam. 2022, 84, 1129–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Nunes, L.; Jiménez, L.; Jesus, S.; Nunes, C.; Hidalgo, V. An Ecological Model of Well-Being in Child Welfare Referred Children. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 140, 811–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenstein, T.; Colasante, T. Socioemotional development in the digital age. Psychol. Inq. 2020, 31, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Ayala, M. Communication techniques used by pediatricians in the well-child program visits: A pilot study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 78, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parents (n = 340) | Children | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | M | SD | Range (Years) | M | SD | Range (Months) | |

| Age | 36.36 | 4.58 | 22–50 | 25.33 | 10.44 | 18–57 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 86.5 | ||||||

| Male | 13.5 | ||||||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 82.6 | ||||||

| Not married | 17.4 | ||||||

| Educational level | |||||||

| Lower school degree | 34.1 | ||||||

| University degree | 65.9 | ||||||

| Employment status | |||||||

| Unemployed | 12.1 | ||||||

| Employed | 87.9 | ||||||

| Number of children per family | 1.59 | 0.65 | 1–2 | ||||

| Working hours per week | 38.48 | 8.62 | 0–63 | ||||

| Children’s Use of Multimedia | % | M | SD | Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Television | Watch TV | Yes | 91.80 | |||

| No | 8.20 | |||||

| Time (daily use min/day) | 83.94 | 79.11 | 0–600 | |||

| Smartphone | Use a device | Yes | 79.70 | |||

| No | 20.30 | |||||

| With adult supervision | Always or most of the time | 67.90 | ||||

| Often | 12.20 | |||||

| Sometimes | 12.90 | |||||

| Touchscreen | Use a device | Yes | 77.60 | |||

| No | 22.40 | |||||

| Time (daily use min/day) | 42.48 | 52.52 | 0–360 | |||

| Total screen exposure | 110.24 | 114.40 | 0–920 | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Paediatric symptoms | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Watch TV | −0.01 | 1 | ||||||

| 3. TV time | 0.18 ** | 0.32 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4. Use touchscreen | 0.07 | 0.17 ** | 0.13 * | 1 | ||||

| 5. Touchscreen time | 0.12 * | 0.12 * | 0.34 ** | 0.44 ** | 1 | |||

| 6. Child’s age | 0.04 | 0.23 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.26 ** | 1 | ||

| 7. Parents’ academic level | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.11 * | −0.07 | −0.19 ** | −0.07 | 1 | |

| 8. Parents’ working hours | −0.16 ** | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.09 | 1 |

| Domains | Boys (n = 184) | Girls (n = 156) | t (df) | p | d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| TV time | 87.99 | 85.40 | 79.18 | 70.97 | 1.02 (338) | 0.307 | 0.11 | |

| Touchscreen time | 38.55 | 53.05 | 47.12 | 51.68 | −1.50 (338) | 0.134 | −0.16 | |

| f | % | f | % | X2 | p | V | ||

| Watch TV | No | 16 | 8.7 | 12 | 7.7 | 0.11 | 0.737 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 168 | 91.3 | 144 | 92.3 | ||||

| Use touchscreen | No | 51 | 27.7 | 25 | 16.0 | 6.65 | 0.010 | 0.14 |

| Yes | 133 | 72.3 | 131 | 84.0 | ||||

| No University Degree (n = 116) | University Degree (n = 224) | t (df) | p | d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Total screen time | 141.16 | 144.80 | 94.22 | 91.26 | 3.18 (163.60) | 0.002 | 0.42 |

| TV time | 96.30 | 91.60 | 77.55 | 71.19 | 1.92 (188.67) | 0.056 | 0.24 |

| Touchscreen time | 56.11 | 65.80 | 35.42 | 42.60 | 3.07 (166.31) | 0.003 | 0.40 |

| Paediatric Symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | ∆R2 | Change in F | β | t | |

| Step 1—Control variables | 0.03 * | - | 4.09 * | ||

| Child’s gender | −0.01 | 0.02 | |||

| Parents’ working hours | −0.16 ** | −2.86 ** | |||

| Step 2—Main effects | 0.04 * | 0.01 | 3.17 | ||

| Child’s gender | −0.00 | −0.07 | |||

| Parents’ working hours | −0.16 | −2.81 ** | |||

| Total screen time | 0.10 | 1.78 # | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rocha, B.; Ferreira, L.I.; Martins, C.; Santos, R.; Nunes, C. The Dark Side of Multimedia Devices: Negative Consequences for Socioemotional Development in Early Childhood. Children 2023, 10, 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10111807

Rocha B, Ferreira LI, Martins C, Santos R, Nunes C. The Dark Side of Multimedia Devices: Negative Consequences for Socioemotional Development in Early Childhood. Children. 2023; 10(11):1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10111807

Chicago/Turabian StyleRocha, Bruno, Laura I. Ferreira, Cátia Martins, Rita Santos, and Cristina Nunes. 2023. "The Dark Side of Multimedia Devices: Negative Consequences for Socioemotional Development in Early Childhood" Children 10, no. 11: 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10111807