Inter-Rater Reliability, Construct Validity, and Feasibility of the Modified “Which Health Approaches and Treatments Are You Using?” (WHAT) Questionnaires for Assessing the Use of Complementary Health Approaches in Pediatric Oncology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

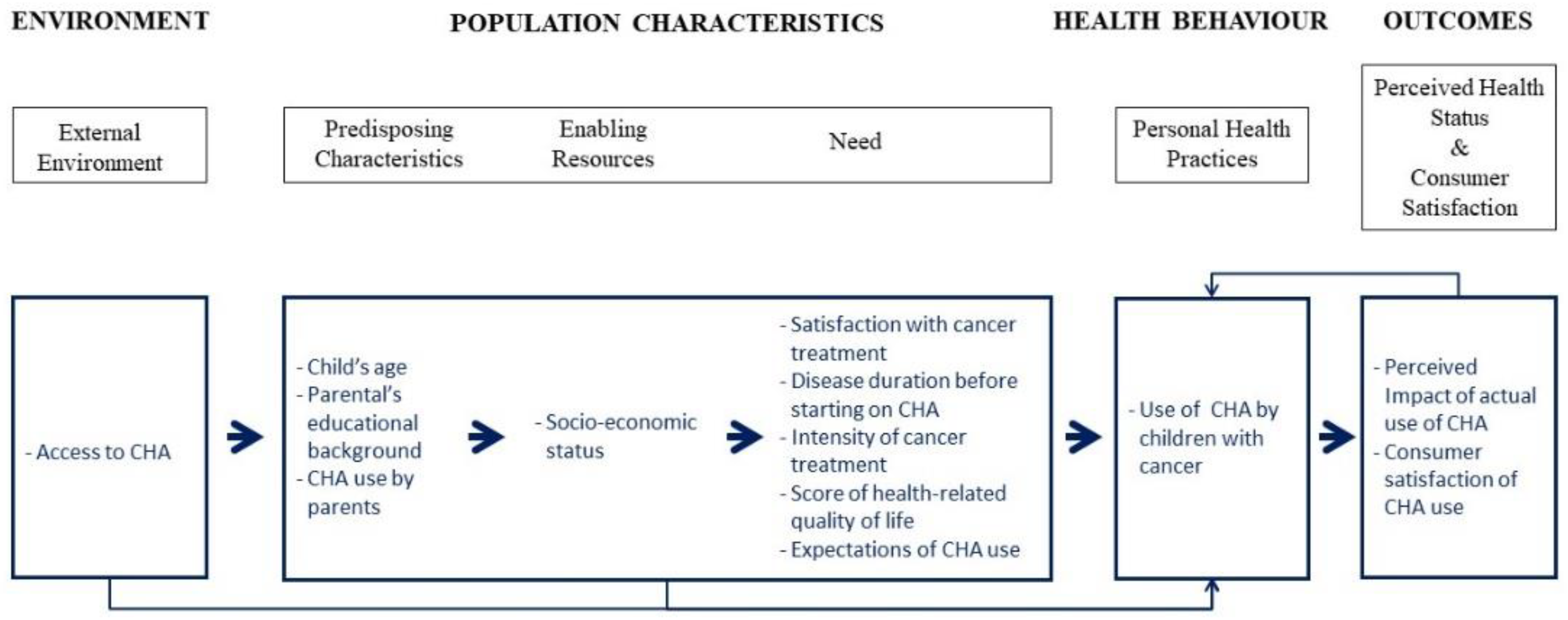

2.1. Hypotheses

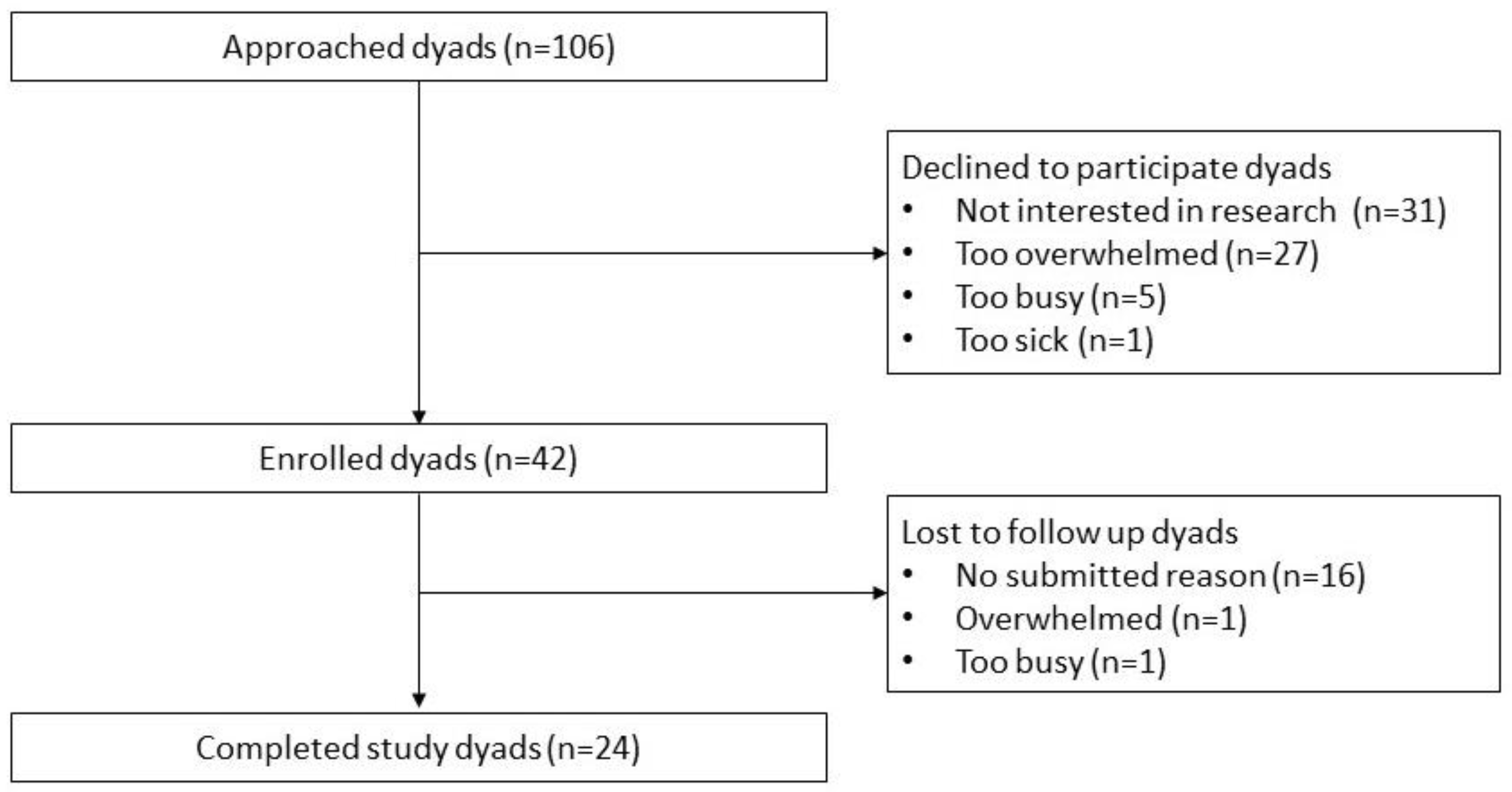

2.2. Participants

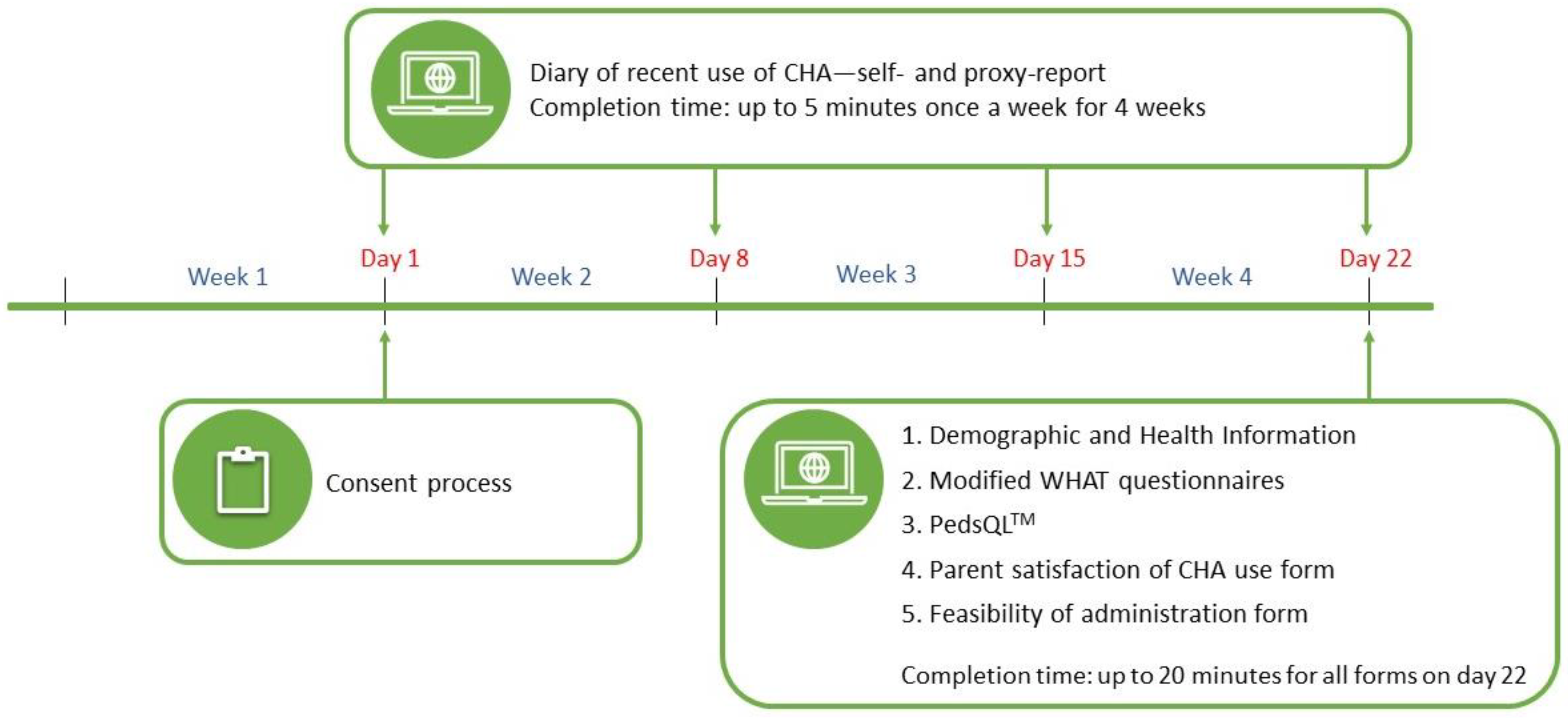

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measures

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Inter-Rater Reliability

3.3. Construct Validity

3.3.1. Convergent Construct Validity

3.3.2. Relationships between Variables Measured via the Modified WHAT and Theoretically Relevant Factors

3.4. Feasibility of Administration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diorio, C.; Lam, C.G.; Ladas, E.; Njuguna, F.; Afungchwi, G.M.; Taromina, K.; Marjerrison, S. Global Use of Traditional and Complementary Medicine in Childhood Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Glob. Oncol. 2017, 3, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s in a Name? Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Luthi, E.; Diezi, M.; Danon, N.; Dubois, J.; Pasquier, J.; Burnand, B.; Rodondi, P.Y. Complementary and alternative medicine use by pediatric oncology patients before, during, and after treatment. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qudimat, M.R.; Rozmus, C.L.; Farhan, N. Family strategies for managing childhood cancer: Using complementary and alternative medicine in Jordan. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, F.L.; Prescott, P.; Chan, Y.K.; Saville, J.; von Elm, E.; Lewith, G.T. Prevalence of complementary medicine use in pediatric cancer: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschling, S.; Reindl, T.; Meyer, S.; Berrang, J.; Henze, G.; Graeber, S.; Ong, M.; Graf, N. Acupuncture to alleviate chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in pediatric oncology—A randomized multicenter crossover pilot trial. Klin. Padiatr. 2008, 220, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reindl, T.K.; Geilen, W.; Hartmann, R.; Wiebelitz, K.R.; Kan, G.; Wilhelm, I.; Lugauer, S.; Behrens, C.; Weiberlenn, T.; Hasan, C.; et al. Acupuncture against chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in pediatric oncology. Interim results of a multicenter crossover study. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2006, 14, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokshi, S.K.; Ladas, E.J.; Taromina, K.; McDaniel, D.; Rooney, D.; Jin, Z.; Hsu, W.C.; Kelly, K.M. Predictors of acupuncture use among children and adolescents with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.M. Bringing evidence to complementary and alternative medicine in children with cancer: Focus on nutrition-related therapies. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2008, 50, 490–493; discussion 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanski, S.L.; Greenwald, M.; Perkins, A.; Simon, H.K. Herbal Therapy Use in a Pediatric Emergency Department Population: Expect the Unexpected. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, M.; Spinetta, J.; Martins, A.; Pessio, A.; Sullivan, M.; D’Angio, G.; Eden, T.; Arush, M.X.S.; Punkko, L.R.; Epelman, C.; et al. Non-Conventional Therapies in Childhood Cancer: Guidelines for Distinguishing Non-Harmful From Harmful Therapies: A Report of the SIOP Working Committee on Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2004, 42, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, R.D.; Rogovik, A.L.; Lai, D.; Vohra, S. Potential interactions of drugnatural health products and natural health products-natural health products among children. J. Pediatr. 2008, 152, 521–526.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.; Gordon, C.; Megason, G. Complementary and alternative medicine use in pediatric hematology/oncology patients at the University of Mississippi. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2013, 60, S84. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanoa, A.; Yong, T.L.; Yeap, S.J.; Lee, I.S.; Singh, V.A. Complementary and alternative medicine use amongst Malaysian orthopaedic oncology patients. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, K.J.; Vohra, S.; Walls, R. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, B.N.; Vincent, N.; Fortier, M.A. Differences in referral and use of complementary and alternative medicine between pediatric providers and patients. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chong, Y.J.; Hie, S.L.; Sultana, R.; Lee, S.H.D.; Chan, W.S.D.; Chan, S.Y.; Cheong, H.H. Complementary and alternative medicines use among pediatric patients with epilepsy in a multiethnic community. Epilepsy Behav. 2016, 60, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, J.F.; Thompson, M.D.; Parks, P.H.; Jacobs, R.Q.; Goyal, M. Caregiver-reported religious beliefs and complementary and alternative medicine use among children admitted to an epilepsy monitoring unit. Epilepsy Behav. 2017, 69, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omari, A.; Al-Qudimat, M.; Abu Hmaidan, A.; Zaru, L. Perception and attitude of Jordanian physicians towards complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in oncology. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2013, 19, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Dagenais, S.; Clifford, T.; Baydala, L.; King, W.J.; Hervas-Malo, M.; Moher, D.; Vohra, S. Complementary and alternative medicine use by pediatric specialty outpatients. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magi, T.; Kuehni, C.E.; Torchetti, L.; Wengenroth, L.; Luer, S.; Frei-Erb, M. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Children with Cancer: A Study at a Swiss University Hospital. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naja, F.; Alameddine, M.; Abboud, M.; Bustami, D.; Al Halaby, R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among pediatric patients with leukemia: The case of Lebanon. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaac-Otero, G.; Molina-Alonso, D.; Asencio-Lopez, L.; Leal-Leal, C. The use of alternative or complementary treatment in pediatric oncologic patients: Survey of 100 cases in a level III attention institute. Gac. Med. Mex. 2016, 152, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sandar, K.; Win Lai, M.; Han, W. Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in children with cancer at Yangon Children’s Hospital. Myanmar Health Sci. Res. J. 2013, 25, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Suen, Y.I.; Gau, B.S.; Chao, S.C. Survey of parents of children with cancer who look for alternative therapies. Ju Li Zhi 2005, 52, 29–38. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Njuguna, F.; Mostert, S.; Seijffert, A.; Musimbi, J.; Langat, S.; van der Burgt, R.H.; Skiles, J.; Sitaresmi, M.N.; van de Ven, P.M.; Kaspers, G.J. Parental experiences of childhood cancer treatment in Kenya. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada [Internet]. Cancer in Young People in Canada: A Report from the Enhanced Childhood Cancer Surveillance System. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Cancda; 2017. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/publications/science-research-data/cancer-young-peoplecanada-surveillance-2017-eng.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Watt, L.; Gulati, S.; Shaw, N.T.; Sung, L.; Dix, D.; Poureslami, I.; Klassen, A.F. Perceptions about complementary and alternative medicine use among Chinese immigrant parents of children with cancer. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toupin April, K.; Stinson, J.; Boon, H.; Duffy, C.M.; Huber, A.M.; Gibbon, M.; Descarreaux, M.; Spiegel, L.; Vohra, S.; Tugwell, P. Development and Preliminary Face and Content Validation of the “Which Health Approaches and Treatments Are You Using?” (WHAT) Questionnaires Assessing Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in Pediatric Rheumatology. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merz, A.; Feifer, D.; Avery, M.; Tsuchiyose, E.; Eche, I.; Awofeso, O.; Wolfe, J.; Dussel, V.; Requena, M.L. Patient-Reported Outcome Benefits for Children with Advanced Cancer and Parents: A Qualitative Study. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2023, 66, e327–e334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudimat, M.R.; Toupin April, K.; Hundert, A.; Jibb, L.; Victor, C.; Nathan, P.C.; Stinson, J. Questionnaires assessing the use of complementary health approaches in pediatrics and their measurement properties: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 53, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudimat, M.R.; Toupin April, K.; Nathan, P.C.; Jibb, L.; Victor, C.; Stinson, J. Validating a questionnaire to assess the use of complementary health approaches in children with cancer: Face and content validity testing (Phase 2). In Proceedings of the 54th Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology, Barcelona, Spain, 28 September–1 October 2022; Pediatric Blood & Cancer: Barcelona, Spain, 2022; p. S528. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Chiarotto, A.; Westerman, M.J.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Mokkink, L.B. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: A Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremeens, J.; Eiser, C.; Blades, M. Factors influencing agreement between child self-report and parent proxy-reports on the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL) generic core scales. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2006, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, D.; Khadka, J.; Mpundu-Kaambwa, C.; Lay, K.; Russo, R.; Ratcliffe, J.; Quality of Life in Kids: Key Evidence to Strengthen Decisions in Australia Project Team. Are We Agreed? Self-Versus Proxy-Reporting of Paediatric Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) Using Generic Preference-Based Measures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2022, 40, 1043–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; McFatrich, M.; Withycombe, J.S.; Maurer, S.H.; Jacobs, S.S.; Lin, L.; Lucas, N.R.; Baker, J.N.; Mann, C.M.; Sung, L.; et al. Agreement Between Child Self-report and Caregiver-Proxy Report for Symptoms and Functioning of Children Undergoing Cancer Treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e202861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndao, D.H.; Ladas, E.J.; Bao, Y.; Cheng, B.; Nees, S.N.; Levine, J.M.; Kelly, K.M. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Among Children, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors: A Survey Study. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 35, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gozum, S.; Arikan, D.; Buyukavci, M. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in Pediatric Oncology Patients in Eastern Turkey. Cancer NursingTM 2007, 30, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladas, E.J.; Rivas, S.; Ndao, D.; Damoulakis, D.; Bao, Y.Y.; Cheng, B.; Kelly, K.M.; Antillon, F. Use of traditional and complementary/alternative medicine (TCAM) in children with cancer in Guatemala. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschling, S.; Meyer, S.; Langler, A.; Scharifi, G.; Ebinger, F.; Gronwald, B. Differences in use of complementary and alternative medicine between children and adolescents with cancer in Germany: A population based survey. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, N.; Graham, D.; O’Meara, A.; Devins, M.; Jennings, V.; O’Leary, D.; O’Reilly, M. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by Irish Pediatric Cancer Patients. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 35, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valji, R.; Adams, D.; Dagenais, S.; Clifford, T.; Baydala, L.; King, W.J.; Vohra, S. Complementary and alternative medicine: A survey of its use in pediatric oncology. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 527163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, I.; Sandler, E.; Garnica, G.R.; Wiltrout, S.A. Factors Influencing Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in a Multisite Pediatric Oncology Practice. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2007, 29, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post-White, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Hageness, S.; Sencer, S.F. Complementary and alternative medicine use in children with cancer and general and specialty pediatrics. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2009, 26, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singendonk, M.; Kaspers, G.J.; Naafs-Wilstra, M.; Meeteren, A.S.; Loeffen, J.; Vlieger, A. High prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in the Dutch pediatric oncology population: A multicenter survey. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 172, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revuelta-Iniesta, R.; Wilson, M.L.; White, K.; Stewart, L.; McKenzie, J.M.; Wilson, D.C. Complementary and alternative medicine usage in Scottish children and adolescents during cancer treatment. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2014, 20, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.V.; Stutzer, C.A.; MacWilliam, L.; Fryer, C. Alternative and complementary therapy use in pediatric oncology patients in British Columbia: Prevalence and reasons for use and non-use. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laengler, A.; Spix, C.; Seifert, G.; Gottschling, S.; Graf, N.; Kaatsch, P. Complementary and alternative treatment methods in children with cancer: A population-based retrospective survey on the prevalence of use in Germany. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 2233–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, D.; Bussieres, J.F.; Theoret, Y.; Lebel, D.; Kish, S.; Moghrabi, A.; Laurier, C. Use of alternative and complementary therapies in children with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2005, 44, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Lin, J.; Kim, M.; Moody, K.P. Pediatric Oncologists’ Views Toward the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Children With Cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2009, 31, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, B.H.; Oxman, A.D. An Assessment of the Sensibility of a Quality-of-Life Instrument. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1993, 11, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudimat, M.R.; Toupin April, K.; Jibb, L.; Victor, C.; Nathan, P.C.; Stinson, J. Assessment of complementary health approaches use in pediatric oncology: Modifying and preliminary validation of the “Which Health Approaches and Treatments Are you Using?” (WHAT) questionnaires. PLoS ONE, 2023; manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, D.; Hogg-Johnson, S. Lecture Notes for the Measurement in Clinical Research Course (HAD5302); Bombardier, C., Wright, J., Davis, A., Young, N., Smith, P., Eds.; The University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Varni, J.W.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Katz, E.R.; Meeske, K.M.; Dickinson, P. The PedsQL™ in Pediatric Cancer: Reliability and Validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer 2002, 94, 2090–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.E.; Shin, J.S.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, M.R.; Choi, A.; Park, K.B.; Lee, H.J.; Ha, I.H. Quality of medical service, patient satisfaction and loyalty with a focus on interpersonal-based medical service encounters and treatment effectiveness: A cross-sectional multicenter study of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) hospitals. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazak, A.E.; Hocking, M.C.; Ittenbach, R.F.; Meadows, A.T.; Hobbie, W.; DeRosa, B.W.; Leahey, A.; Kersun, L.; Reilly, A. Revision of the Intensity of Treatment Rating Scale: Classifying the Intensity of Pediatric Cancer Treatment. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2012, 59, 69–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 28.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Baharum, N. Guidelines of the minimum sample size requirements for Cohen’s Kappa. Epidemiol. Biostat. Public Health 2017, 14, e12267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlson, C.W.; Rapoff, M.A. Attrition in randomized controlled trials for pediatric chronic conditions. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matza, L.S.; Patrick, D.L.; Riley, A.W.; Alexander, J.J.; Rajmil, L.; Pleil, A.M.; Bullinger, M. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: Report of the ISPOR PRO good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force. Value Health 2013, 16, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bot, S.D.; Terwee, C.B.; van der Windt, D.A.; Bouter, L.M.; Dekker, J.; de Vet, H.C. Clinimetric evaluation of shoulder disability questionnaires: A systematic review of the literature. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2004, 63, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangunkusumo, R.T.; Duisterhout, J.S.; de Graaff, N.; Maarsingh, E.J.; de Koning, H.J.; Raat, H. Internet versus paper mode of health and health behavior questionnaires in elementary schools: Asthma and fruit as examples. J. Sch. Health 2006, 76, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussaffi, H.; Omer, R.; Prais, D.; Mei-Zahav, M.; Weiss-Kasirer, T.; Botzer, Z.; Blau, H. Computerised paediatric asthma quality of life questionnaires in routine care. Arch. Dis. Child. 2007, 92, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Raat, H.; Mangunkusumo, R.T.; Landgraf, J.M.; Kloek, G.; Brug, J. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of adolescent health status measurement by the Child Health Questionnaire Child Form (CHQ-CF): Internet administration compared with the standard paper version. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.W.; Limbers, C.A.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Bryant, W.P.; Wilson, D.P. The ePedsQL in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Internet administration. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N.L.; Varni, J.W.; Snider, L.; McCormick, A.; Sawatzky, B.; Scott, M.; King, G.; Hetherington, R.; Sears, E.; Nicholas, D. The Internet is valid and reliable for child-report: An example using the Activities Scale for Kids (ASK) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL). J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, A. A multi-dimensional model of clinical utility. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2006, 18, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulley, S.B.; Cummings, S.R.; Browner, W.S.; Grady, D.G.; Newman, T.B. Designing Clinical Research, 4th ed.; Eolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, M.; Alexander, S.; Shama, W.; Mills, D.; Desjardins, L.; Hancock, K. Perceived benefits of and barriers to psychosocial risk screening in pediatric oncology by health care providers. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e27429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Focus on Research Methods—Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada, Census of Population 2021: Immigration, Place of Birth, and Citizenship. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/dt-td/Index-eng.cfm?LANG=E&SUB=98P1008&SR=0&RPP=10&SORT=releasedate (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Afungchwi, G.M.; Hesseling, P.B.; Ladas, E.J. The role of traditional healers in the diagnosis and management of Burkitt lymphoma in Cameroon: Understanding the challenges and moving forward. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afungchwi, G.M.; Kruger, M.; Hesseling, P.; van Elsland, S.; Ladas, E.J.; Marjerrison, S. Survey of the use of traditional and complementary medicine among children with cancer at three hospitals in Cameroon. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiasuddin, A.; Wong, J.; Siu, A.M. Ethnicity, traditional healing practices, and attitudes towards complementary medicine of a pediatric oncology population receiving healing touch in Hawaii. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 2, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, V.; Castillo, L.; Ladas, E.J.; Lin, M.; Ginn, E.; Kelly, K.M.; Cacciavillano, W.; Chantada, G. Beliefs and determinants of use of traditional complementary/alternative medicine in pediatric patients who undergo treatment for cancer in South America. J. Glob. Oncol. 2017, 3, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, H.; Lai, D.; Johnson, D.; Verhoef, M.; Musto, R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among Chinese and white Canadians. Can. Fam. Physician 2008, 54, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roth, M.A.; Kobayashi, K.M. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Chinese Canadians: Results from a national survey. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2008, 10, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questionnaires | Type | # of Items | Content | Time (min) | Evidence of Reliability and Validity | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diary of CHA use | Self-report | 3 | Items:

| <5 |

| H2: Convergent construct validity |

| Proxy-report | 3 | <5 | ||||

| WHAT | Self-report | 13 | Domains:

| 10 |

| H1: Inter-rater reliability H2: Convergent construct validity H3: Hypotheses testing |

| Proxy-report | 15 | 10 | ||||

| Feasibility of administration | Self-report | 5 | Adapted items: the WHAT was

| 2 |

| H4: Feasibility of administration |

| Proxy-report | 5 | 2 | ||||

| PedsQL | Self-report | 23 | Domains:

| <5 |

| H3: Hypotheses testing |

| Proxy-report | 23 | <5 | ||||

| Satisfaction of CHA use | Proxy-report | 4 | Adapted items:

| <1 |

| H3: Hypotheses testing |

| ITR 3.0 | Chart review | 4 | Items:

| N/A |

| H3: Hypotheses testing |

| Children, n = 24 | |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 14.3 (2.8) |

| Female sex. n (%) | 12 (50) |

| School grade level, n (%) | |

| Grade 3 | 1 (4.2) |

| Grade 4 | 2 (8.3) |

| Grade 5 | 1 (4.2) |

| Grade 6 | 3 (12.5) |

| Grade 8 | 1 (4.2) |

| Grade 9 | 4 (16.7) |

| Grade 10 | 4 (16.7) |

| Grade 11 | 4 (16.7) |

| Grade 12 | 2 (8.3) |

| Child’s cancer diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Lymphoma | 8 (33.3) |

| Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | 5 (20.8) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 2 (8.3) |

| Ewing sarcoma | 3 (12.5) |

| Osteosarcoma | 2 (8.3) |

| Central nervous system tumour | 2 (8.3) |

| Neuroblastoma | 1 (4.5) |

| Other cancer diagnosis | 1 (4.2) |

| Duration of illness in years, mean (SD) | 2.8 (3.8) |

| Diagnosed with relapsed cancer, n (%) | 3 (12.5) |

| Cancer treatment +, n (%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 23 (95.8) |

| Radiation therapy | 9 (37.5) |

| Immunotherapy | 5 (20.8) |

| Surgery | 4 (16.7) |

| Stem Cell Transplant | 2 (8.3) |

| Other treatments | 2 (8.3) |

| Intensity of treatment score, mean (SD) | 3 (0.5) |

| Child’s PedsQL score (self-report), mean (SD) | 58.3 (15.2) |

| Parents, n = 24 | |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 42.4 (8.6) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 18 (75) |

| Parent’s relationship with the child, n (%) | |

| Biological mother | 17 (70.8) |

| Biological father | 6 (25) |

| Other | 1 (4.2) |

| Parent’s marital status, n (%) | |

| Married or living common-law | 19 (79.2) |

| Separated | 2 (8.3) |

| Divorced | 2 (8.3) |

| Single | 1 (4.2) |

| Child’s caregiver at home, n (%) | |

| Child lives with one parent (mother or father) | 4 (16.7) |

| Child lives with both parents | 20 (83.3) |

| Ethnic background, n (%) | |

| White (Caucasian) | 9 (37.5) |

| Black (e.g., African, Haitian, Jamaican, Somali) | 8 (33.3) |

| Arab/West Asian (e.g., Armenian, Egyptian, Iranian, Lebanese, Moroccan) | 3 (12.5) |

| South East Asian | 2 (8.3) |

| Latin American | 1 (4.2) |

| South Asian | 1 (4.2) |

| Educational background, n (%) | |

| Graduated secondary/high school | 3 (12.5) |

| Some college/technical school | 1 (4.2) |

| Graduated college/technical school | 3 (12.5) |

| Graduate degree | 14 (58.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (12.5) |

| Work status, n (%) | |

| Full-time | 10 (41.7) |

| Not working | 7 (29.2) |

| Part-time | 4 (16.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (12.5) |

| Spouse’s educational background, n (%) | |

| Some high school | 1 (4.2) |

| Graduated secondary/high school | 3 (12.5) |

| Graduated college/technical school | 3 (12.5) |

| Some graduate school | 1 (4.2) |

| Graduate degree | 8 (33.3) |

| Other degree | 1 (4.2) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (8.3) |

| Missing data | 5 (20.8) |

| Spouse’s work status, n (%) | |

| Full-time | 8 (33.3) |

| Part-time | 4 (16.7) |

| Not working | 4 (16.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (12.5) |

| Missing data | 5 (20.8) |

| Household annual income in Canadian Dollar, n (%) | |

| Less than $24,999 | 2 (8.3) |

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 10 (41.7) |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 1 (4.2) |

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 3 (12.5) |

| $200,000 or more | 2 (8.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 (20.8) |

| Number of people live in the household, mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.6) |

| CHA use by parents, n (%) | |

| Yes | 11 (45.8) |

| CHA use intensity, n (%) | |

| High (more than five types of CHA) | 2 (8.3) |

| Medium (2–4 types of CHA) | 4 (16.7) |

| Low (1 type of CHA) | 5 (20.8) |

| No use of CHA | 13 (54.2) |

| Parent’s expectations of the child’s CHA use +, n (%) | |

| CHA use would let the child feel better | 17 (70.8) |

| CHA use would prevent the child’s illness/symptom | 2 (8.3) |

| CHA use was safe to use | 2 (8.3) |

| Other | 2 (8.3) |

| CHA use would treat the child’s symptoms | 1 (4.2) |

| Parent’s satisfaction of child’s recent CHA use outcome, n (%) | |

| Dissatisfied | 4 (16.7) |

| Neutral | 13 (54.2) |

| Satisfied | 5 (20.8) |

| Very satisfied | 2 (8.3) |

| Parent’s satisfaction of CHA cost, n (%) | |

| Very dissatisfied | 1 (4.2) |

| Dissatisfied | 8 (33.3) |

| Neutral | 6 (25) |

| Satisfied | 7 (28.2) |

| Very satisfied | 1 (4.2) |

| Not applicable | 1 (4.2) |

| Parent’s satisfaction of CHA availability, n (%) | |

| Dissatisfied | 3 (12.5) |

| Neutral | 12 (50) |

| Satisfied | 8 (33.3) |

| Very satisfied | 1 (4.2) |

| Parent’s satisfaction of the safety of CHA, n (%) | |

| Dissatisfied | 2 (8.3) |

| Neutral | 11 (45.8) |

| Satisfied | 10 (41.7) |

| Very satisfied | 1 (4.2) |

| Monthly cost of CHA in Canadian Dollar, mean (SD) | 155 (168) |

| Awareness of HCPs about child’s use of CHA (parent’s report), n (%) | |

| Yes | 7 (29.2) |

| No | 7 (29.2) |

| Do not know | 10 (41.7) |

| Parent’s satisfaction with conventional treatments, n (%) | |

| Very satisfied | 3 (12.5) |

| Satisfied | 15 (62.5) |

| Neutral | 6 (25) |

| Child’s PedsQL score (proxy-report), mean (SD) | 56.3 (15) |

| Raters | Weighted Kappa (SE) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Dyad 1 | 0.087 (0.089) * | −0.086 to 0.261 |

| Dyad 2 | 0.756 (0.065) | 0.628 to 0.884 |

| Dyad 3 | 0.540 (0.094) | 0.357 to 0.724 |

| Dyad 4 | 0.686 (0.079) | 0.532 to 0.841 |

| Dyad 5 | 0.867 (0.053) | 0.763 to 0.972 |

| Dyad 6 | 0.987 (0.009) | 0.968 to 1.005 |

| Dyad 7 | 0.890 (0.037) | 0.819 to 0.962 |

| Dyad 8 | 0.232 (0.143) * | −0.048 to 0.512 |

| Dyad 9 | 0.768 (0.061) | 0.648 to 0.888 |

| Dyad 10 | 0.794 (0.116) | 0.567 to 1.021 |

| Dyad 11 | 0.950 (0.019) | 0.912 to 0.988 |

| Dyad 12 | 0.835 (0.052) | 0.734 to 0.936 |

| Dyad 13 | 0.976 (0.016) | 0.944 to 1.008 |

| Dyad 14 | 0.962 (0.028) | 0.907 to 1.016 |

| Dyad 15 | 0.981 (0.019) | 0.943 to 1.019 |

| Dyad 16 | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 to 1.000 |

| Dyad 17 | 0.853 (0.053) | 0.750 to 0.957 |

| Dyad 18 | 0.615 (0.085) | 0.448 to 0.782 |

| Dyad 19 | 0.676 (0.053) | 0.573 to 0.780 |

| Dyad 20 | 0.749 (0.074) | 0.604 to 0.893 |

| Dyad 21 | 0.886 (0.082) | 0.725 to 1.047 |

| Dyad 22 | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 to 1.000 |

| Dyad 23 | 0.630 (0.084) | 0.465 to 0.795 |

| Dyad 24 | 0.763 (0.044) | 0.677 to 0.848 |

| All Dyads | 0.770 (0.056) | 0.660 to 0.881 |

| Respondents | Weighted Kappa (SE) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Child 2 | 0.951 (0.037) | 0.878 to 1.023 |

| Child 3 | 0.000 (0.000) * | 0.000 to 0.000 |

| Child 4 | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 to 1.000 |

| Child 5 | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 to 1.000 |

| Child 6 | 0.746 (0.069) | 0.610 to 0.881 |

| Child 7 | 0.861 (0.090) | 0.685 to 1.037 |

| Child 8 | 0.000 (0.000) * | 0.000 to 0.000 |

| Child 9 | 0.865 (0.052) | 0.763 to 0.967 |

| Child 11 | 0.931 (0.053) | 0.826 to 1.036 |

| Child 12 | 0.821 (0.097) | 0.632 to 1.011 |

| Child 13 | 0.947 (0.050) | 0.849 to 1.045 |

| Child 14 | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 to 1.000 |

| Child 15 | 0.943 (0.057) | 0.831 to 1.055 |

| Child 17 | 0.884 (0.089) | 0.709 to 1.059 |

| Child 18 | 0.668 (0.133) | 0.406 to 0.929 |

| Child 19 | 0.770 (0.079) | 0.616 to 0.924 |

| Child 20 | 0.945 (0.058) | 0.832 to 1.057 |

| Child 23 | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 to 1.000 |

| Child 24 | 0.976 (0.018) | 0.941 to 1.010 |

| All children | 0.806 (0.046) | 0.715 to 0.897 |

| Respondents | Weighted Kappa (SE) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Parent 1 | 0.817 (0.101) | 0.618 to 1.015 |

| Parent 2 | 0.968 (0.024) | 0.921 to 1.014 |

| Parent 3 | 0.880 (0.060) | 0.764 to 0.997 |

| Parent 4 | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 to 1.000 |

| Parent 5 | 0.951 (0.049) | 0.855 to 1.046 |

| Parent 6 | 0.743 (0.065) | 0.616 to 0.871 |

| Parent 7 | 0.848 (0.100) | 0.653 to 1.044 |

| Parent 9 | 0.749 (0.101) | 0.551 to 0.947 |

| Parent 11 | 0.967 (0.025) | 0.917 to 1.016 |

| Parent 12 | 0.888 (0.070) | 0.751 to 1.026 |

| Parent 13 | 0.941 (0.055) | 0.832 to 1.049 |

| Parent 14 | 0.975 (0.025) | 0.926 to 1.025 |

| Parent 15 | 0.880 (0.086) | 0.711 to 1.048 |

| Parent 17 | 0.944 (0.058) | 0.831 to 1.058 |

| Parent 18 | 0.846 (0.094) | 0.661 to 1.031 |

| Parent 19 | 0.789 (0.074) | 0.644 to 0.934 |

| Parent 20 | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 to 1.000 |

| Parent 23 | 0.879 (0.064) | 0.753 to 1.005 |

| Parent 24 | 0.926 (0.033) | 0.861 to 0.991 |

| All parents | 0.894 (0.057) | 0.782 to 1.006 |

| Recent Use of CHA | Child Self-Report (n = 24) | Parent Proxy-Report (n = 24) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHA Users (n = 18) | CHA Non-User (n = 6) | CHA Users (n = 19) | CHA Non-User (n = 5) | |||||

| Variables | n (%) | n (%) | p-value ^ | n (%) | n (%) | p-value ^ | ||

| Easy access to CHA | ||||||||

| Yes | 14 (77.8%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0.020 * | 16 (84.2%) | 0 | <0.001 * | ||

| Parental education | ||||||||

| Graduated secondary/high school | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0.373 | 2 (10.5%) | 1 (20%) | 0.452 | ||

| Some college/technical school | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 1 (20%) | ||||

| Graduated college/technical school | 3 (16.7%) | 0 | 3 (15.8%) | 0 | ||||

| Graduate degree | 10 (55.6%) | 4 (66.7) | 11 (57.9%) | 3 (60%) | ||||

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (16.7%) | 0 | 3 (15.8%) | 0 | ||||

| Parent’s use of CHA | ||||||||

| Yes | 8 (44.4%) | 3 (50%) | 1.000 | 9 (81.8%) | 2 (40%) | 1.000 | ||

| Family annual income | ||||||||

| Less than $24,999 | 2 (11.1%) | 0 | 0.736 | 2 (10.5%) | 0 | 0.656 | ||

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 7 (38.9%) | 3 (50%) | 8 (42.1%) | 2 (40%) | ||||

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 1 (5.3%) | 0 | ||||

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 1 (5.6%) | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (5.3%) | 2 (40%) | ||||

| $150,000 to $199.999 | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 1 (5.3%) | |||||

| $200,000 or more | 2 (11.1%) | 0 | 2 (10.5%) | 0 | ||||

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (16.7%) | 4 (21.1%) | 1 (20%) | ||||

| Parent’s employment status | ||||||||

| Full-time | 6 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7) | 0.124 | 8 (42.1%) | 2 (40%) | 0.499 | ||

| Part-time | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (33.3%) | 2 (10.5%) | 2 (40%) | ||||

| Not working | 7 (38.9%) | 0 | 6 (31.6%) | 1 (20%) | ||||

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (16.7%) | 0 | 3 (15.8%) | 0 | ||||

| Parent’s expectation of child’s use of CHA | ||||||||

| Feel better | 13 (72.2%) | 4 (66.7%) | 0.632 | 14 (73.7%) | 3 (60%) | 0.518 | ||

| Prevent illness/symptoms | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (20%) | ||||

| Treat symptoms | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 1 (5.3%) | 0 | ||||

| Safe to use | 2 (11.1%) | 0 | 2 (10.5%) | 0 | ||||

| Other | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (20%) | ||||

| Parent’s satisfaction with conventional treatment | ||||||||

| Very satisfied | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1.000 | 3 (15.8%) | 0 | 1.000 | ||

| Satisfied | 11 (61.1%) | 4 (66.7%) | 11 (57.9%) | 4 (80%) | ||||

| Neutral | 5 (27.8%) | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (26.3%) | 1 (20%) | ||||

| Median (Range) | Median (Range) | U | p-value | Median (Range) | Median (Range) | U | p-value | |

| Child’s age (y) | 14.9 (8.5–18) | 16.2 (9.8–17.3) | 30 | 0.109 | 15.3 (10.5–17.1) | 11.8 (8.5–18) | 27 | 0.145 |

| Period since cancer diagnosis (y) | 1.3 (0.3–15.8) | 0.9 (0.2–10.4) | 51 | 0.841 | 1.5 (0.3–15.8) | 1.4 (0.4–5.3) | 36 | 0.413 |

| PedsQL score | 60.9 (28.3–77.2) | 58.7 (45.7–80.4) | 47 | 0.640 | 55 (32.6–83.7) | 56.5 (30.4–80.4) | 32.5 | 0.286 |

| Intensity of cancer treatment | 3 (2–4) | 3 (3–4) | 52 | 0.873 | 3 (2–4) | 3 (3–4) | 28.5 | 0.107 |

| Parent’s satisfaction of CHA use | 4 (3–5) | 4 (0–4.5) | 48 | 0.710 | 3.1 (2.3–4) | 3 (2–4) | 43 | 0.773 |

| CHA monthly cost (CAD) | 100 (0–500) | 127.5 (0–500) | 42.5 | 0.436 | 100 (0–500) | 50 (0–50) | 36 | 0.427 |

| Future use of CHA | Yes (n = 27) | No or not sure (n = 3) | Yes (n = 32) | No or not sure (n = 2) | ||||

| Variables | n (%) | n (%) | p-value ^ | n (%) | n (%) | p-value ^ | ||

| Helpfulness of recent use of CHA + | ||||||||

| Helpful | 14 (51.9%) | 1/3 (33.3%) | 0.446 | 14 (43.8%) | 1 (50%) | 1.000 | ||

| Somewhat helpful | 11 (40.7% | 1/3 (33.3%) | 16 (50%) | 1 (50%) | ||||

| Not sure | 2 (7.4%) | 1/3 (33.3%) | 2 (6.3%) | 0 | ||||

| Future use of CHA | Yes (n = 14) | No or not sure (n = 3) | Yes (n = 17) | No or not sure (n = 7) | ||||

| Variables | Median (Range) | Median (Range) | U | p-value | Median (Range) | Median (Range) | U | p-value |

| CHA monthly cost (CAD) | 100 (100–500) | 50 (0–500) | 47 | 0.420 | 100 (0–500) | 155 (0–500) | 54 | 0.723 |

| Parent’s satisfaction of CHA use | 4 (3–5) | 4 (0–4.5) | 42 | 0.260 | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2.3–5) | 57 | 0.872 |

| Administration Feasibility Questions | Child’s Self-Report n = 24 | Parents’ Proxy-Report n = 24 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Cronbach’s Alpha | Mean (SD) | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

| Were the instructions and questions in the WHAT questionnaire easy to understand? * | 5.54 (1.29) | 0.853 | 5.67 (1.37) | 0.829 |

| Was the WHAT questionnaire easy to use? * | 5.67 (1.72) | 5.83 (1.69) | ||

| If you were given the WHAT questionnaire, would you complete it? * | 5.71 (1.06) | 5.83 (1.05) | ||

| Was the layout of the WHAT questionnaire easy to follow? * | 5.63 (1.52) | 5.83 (1.38) | ||

| How would you rate the amount of time taken to complete the WHAT questionnaire? ** | 5.67 (1.40) | 5.88 (1.36) | ||

| Overall | 5.64 (0.23) | 5.81 (0.22) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alqudimat, M.R.; Toupin April, K.; Jibb, L.; Victor, C.; Nathan, P.C.; Stinson, J. Inter-Rater Reliability, Construct Validity, and Feasibility of the Modified “Which Health Approaches and Treatments Are You Using?” (WHAT) Questionnaires for Assessing the Use of Complementary Health Approaches in Pediatric Oncology. Children 2023, 10, 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091500

Alqudimat MR, Toupin April K, Jibb L, Victor C, Nathan PC, Stinson J. Inter-Rater Reliability, Construct Validity, and Feasibility of the Modified “Which Health Approaches and Treatments Are You Using?” (WHAT) Questionnaires for Assessing the Use of Complementary Health Approaches in Pediatric Oncology. Children. 2023; 10(9):1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091500

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqudimat, Mohammad R., Karine Toupin April, Lindsay Jibb, Charles Victor, Paul C. Nathan, and Jennifer Stinson. 2023. "Inter-Rater Reliability, Construct Validity, and Feasibility of the Modified “Which Health Approaches and Treatments Are You Using?” (WHAT) Questionnaires for Assessing the Use of Complementary Health Approaches in Pediatric Oncology" Children 10, no. 9: 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091500

APA StyleAlqudimat, M. R., Toupin April, K., Jibb, L., Victor, C., Nathan, P. C., & Stinson, J. (2023). Inter-Rater Reliability, Construct Validity, and Feasibility of the Modified “Which Health Approaches and Treatments Are You Using?” (WHAT) Questionnaires for Assessing the Use of Complementary Health Approaches in Pediatric Oncology. Children, 10(9), 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091500