High-Power Ultrasonic Synthesis and Magnetic-Field-Assisted Arrangement of Nanosized Crystallites of Cobalt-Containing Layered Double Hydroxides

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

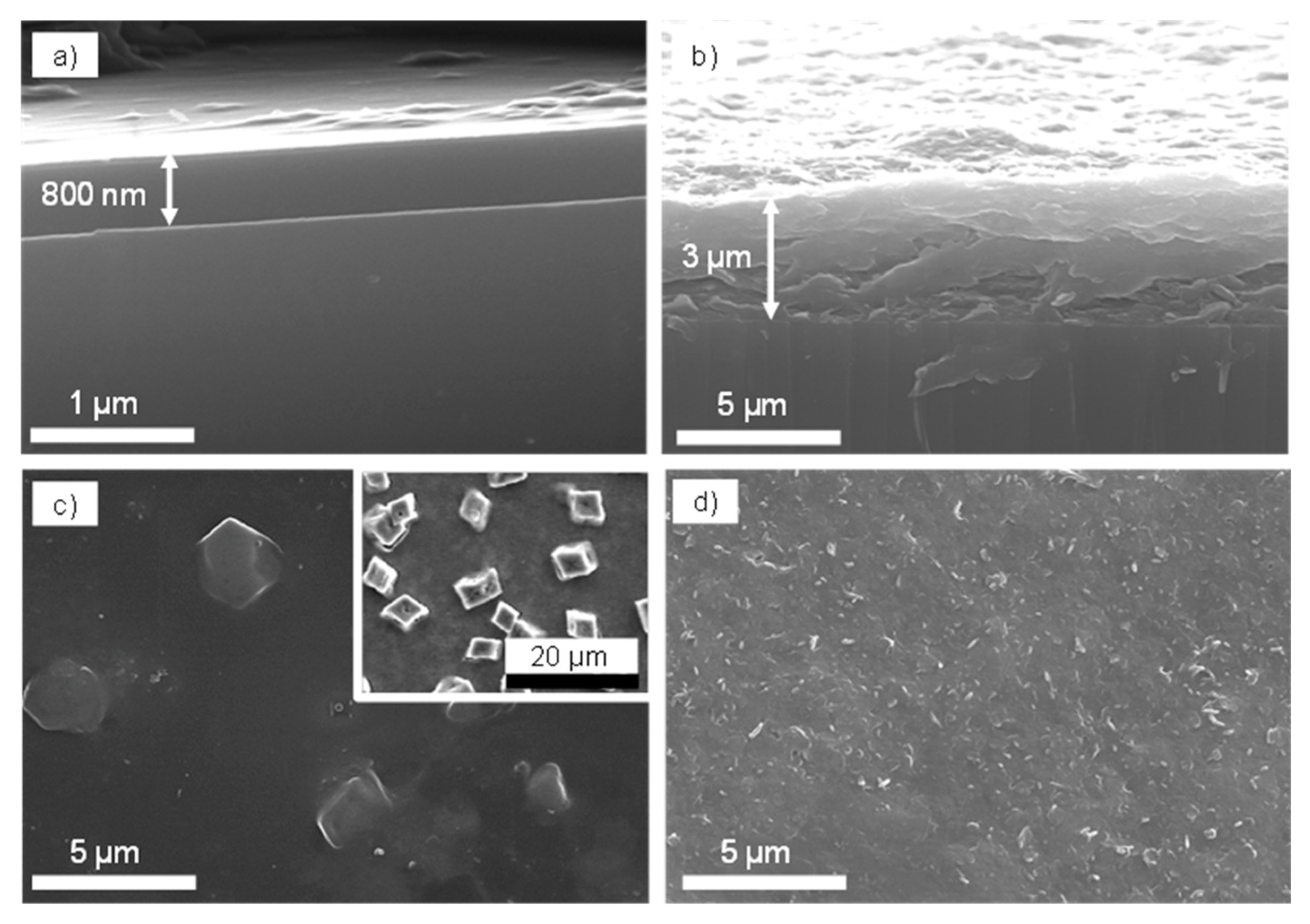

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mills, S.; Christy, A.; Génin, J.; Kameda, T.; Colombo, F. Nomenclature of the hydrotalcite supergroup: Natural layered double hydroxides. Miner. Mag. 2012, 76, 1289–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.G.; Slade, R.C.T. Structural aspects of Layered Double Hydroxides. Struct. Bond. 2006, 119, 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rives, V. Double Hydroxides: Present and Future; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; 439p. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, S.P.; Jones, W. Layered Double Hydroxides as Templates for the Formation of Supramolecular Structures. In Supramolecular Organization and Materials Design; Jones, W., Rao, C.N.R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 295–331. [Google Scholar]

- Serdechnova, M.; Salak, A.N.; Barbosa, F.S.; Vieira, D.E.L.; Tedim, J.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Interlayer intercalation and arrangement of 2-mercaptobenzothiazolate and 1,2,3-benzotriazolate anions in layered double hydroxides: In situ x-ray diffraction study. J. Solid State Chem. 2016, 233, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S. The syntheses of hydrotalcite-like compounds and their structures and physico-chemical properties-I: The Systems Mg2+-Al3+-NO3-, Mg2+-Al3+-Cl−, Mg2+-Al3+-ClO4−, Ni2+-Al3+-Cl− and Zn2+-Al3+-Cl−. Clays Clay Miner. 1975, 23, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S.; Okada, A. Synthesis of hydrotalcite-like compounds and their physico-chemical properties—The system Mg2+-Al3+-SO42- and Mg2+-Al3+-CrO42−. Clays Clay Miner. 1977, 25, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S.; Kimura, T. Synthesis of new hydrotalcite-like compounds and their physicochemical properties. Chem. Lett. 1973, 2, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.P.; Zeng, H.C. Abrupt structural transformation in hydrotalcite-like compounds Mg1-xAlx(OH)2(NO3)x nH2O as a continuous function of nitrate anions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 1743–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salak, A.N.; Tedim, J.; Kuznetsova, A.I.; Vieira, L.G.; Ribeiro, J.L.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Thermal behavior of layered double hydroxide Zn-Al-pyrovanadate: Composition, structure transformations, and recovering ability. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 4152–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, G.; Dash, B.; Pandey, S. Layered double hydroxides: A brief review from fundamentals to application as evolving biomaterials. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 153, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, V.R.R.; De Souza, R.B.; Da Fonseca Martins, A.M.C.R.P.; Koh, I.H.J.; Constantino, V.R.L. Accessing the biocompatibility of layered double hydroxide by intramuscular implantation: Histological and microcirculation evaluation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Preparation of layered double hydroxides and their applications as additives in polymers, as precursors to magnetic materials and in biology and medicine. Chem. Comm. 2006, 5, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalawade, P.; Aware, B.; Kadam, V.J.; Hirlekar, R.S. Layered double hydroxides: A review. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2009, 68, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, C.S.; Bastos, A.C.; Salak, A.N.; Starykevich, M.; Rocha, D.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Cunha, A.; Almeida, A.; Tedim, J.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Layered double hydroxide clusters as precursors of novel multifunctional layers: A bottom-up approach. Coatings 2019, 9, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J.; Caetano, A.F.; Kuznetsova, A.; Maia, F.; Salak, A.N.; Tedim, J.; Scharnagl, N.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Polyelectrolyte-modified layered double hydroxide nanocontainers as vehicles for combined inhibitors. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 39916–39929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poznyak, S.K.; Tedim, J.; Rodrigues, L.M.; Salak, A.N.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Dick, L.F.P.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Novel inorganic host layered double hydroxides intercalated with guest organic inhibitors for anticorrosion applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2009, 1, 2353–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, D.; Hankari, S.; El Zou, Y.; Wang, S. Recent progress on layered double hydroxides and their derivatives for electrocatalytic water splitting. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Goswami, A.; Asefa, T. Efficient noble metal-free (electro) catalysis of water and alcohol oxidations by zinc–cobalt layered double hydroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 17242–17245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.H.; Lim, T.T.; Dong, Z. Application of layered double hydroxides for removal of oxyanions: A review. Water Res. 2008, 42, 1343–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salak, A.N.; Lisenkov, A.D.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Carbonate-free Zn-Al (1:1) layered double hydroxide film directly grown on zinc-aluminum alloy coating. ECS Electrochem. Lett. 2014, 3, C9–C11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, P.; Pérez-Bernal, M.E.; Ruano-Casero, R.J.; Ananias, D.; Almeida Paz, F.A.; Rocha, J.; Rives, V. Luminescence properties of lanthanide-containing layered double hydroxides. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2016, 226, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalenskaite, A.; Vieira, D.E.L.; Salak, A.N.; Ferreira, M.G.S.; Katelnikovas, A.; Kareiva, A. A comparative study of co-precipitation and sol-gel synthetic approaches to fabricate cerium-substituted Mg-Al layered double hydroxides with luminescence properties. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 143, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalenskaite, A.; Salak, A.N.; Kareiva, A. Induced neodymium luminescence in sol-gel derived layered double hydroxides. Mendeleev Commun. 2018, 28, 493–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intissar, M.; Segni, R.; Payen, C.; Besse, J.P.; Leroux, F. Trivalent cation substitution effect into layered double hydroxides Co2FeyAl1-y(OH)6Cl nH2O: Study of the local order. Ionic conductivity and magnetic properties. J. Solid State Chem. 2002, 167, 508–516. [Google Scholar]

- Coronado, E.; Galan-Mascaros, J.R.; Marti-Gastaldo, C.; Ribera, A.; Palacios, E.; Castro, M.; Burriel, R. Spontaneous magnetization in Ni-Al and Ni-Fe layered double hydroxides. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 9103–9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansa, J.J.; Coronado, E.; Martí-Gastaldo, C.; Ribera, A. Magnetic properties of NiIICrIII layered double hydroxide materials. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 2008, 5642–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, E.; Martí-Gastaldo, C.; Navarro-Moratalla, E.; Ribera, A. Intercalation of [M(ox)3]3− (M = Cr, Rh) complexes into NiIIFeIII-LDH. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 48, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannelli, F.; Zaghrioui, M.; Autret-Lambert, C.; Delorme, F.; Seron, A.; Chartier, T.; Pignon, B. Magnetic properties of Ni(II)-Mn(III) LDHs. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, G.; Martí-Gastaldo, C.; Ribera, A.; Coronado, E. Hybrid materials based on magnetic layered double hydroxides: A molecular perspective. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1601–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, G.; Jordá, J.L.; Atienzar, P.; Varela, M.; Jaafar, M.; Gómez-Herrero, J.; Zamora, F.; Ribera, A.; García, H.; Coronado, E. Stimuli-responsive hybrid materials: Breathing in magnetic layered double hydroxides induced by a thermoresponsive molecule. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, J.A.; Cardona-Serra, S.; Clemente-Juan, J.M.; Gaita-Ariño, A.; Abellán, G.; Coronado, E. Deciphering the role of dipolar interactions in magnetic layered double hydroxides. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 2013–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.A.; Abellán, G.; Coronado, E. Influence of morphology in the magnetic properties of layered double hydroxides. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.E.L.; Salak, A.N.; Fedorchenko, A.V.; Pashkevich, Y.G.; Fertman, E.L.; Desnenko, V.A.; Babkin, R.Y.; Čižmár, E.; Feher, A.; Lopes, A.B.; et al. Magnetic phenomena in Co-containing layered double hydroxides. Low Temp. Phys. 2017, 4, 1214–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babkin, R.Y.; Pashkevich, Y.G.; Fedorchenko, A.V.; Fertman, E.L.; Desnenko, V.A.; Prokhvatilov, A.I.; Galtsov, N.N.; Vieira, D.E.L.; Salak, A.N. Impact of temperature dependent octahedra distortions on magnetic properties of Co-containing double layered hydroxides. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 473, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Wei, M.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Magnetic-field-assisted assembly of CoFe layered double hydroxide ultrathin films with enhanced electrochemical behavior and magnetic anisotropy. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 3171–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, M.; Xu, X.; Han, J.; Zhao, J.; Shi, W.; Kong, X.; Wei, M.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Magnetic-field-assisted assembly of layered double hydroxide/metal porphyrin ultrathin films and their application for glucose sensors. Langmuir 2011, 27, 8233–8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastami, T.R.; Entezari, M.H. Synthesis of manganese oxide nanocrystal by ultrasonic bath: Effect of external magnetic field. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012, 19, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, R.A.; Ashokkumar, M.; Grieser, F. Sonochemical formation of colloidal platinum. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2000, 16, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Jones, R.C.; Caruntu, D.; O’Connor, C.J.; Tarr, M.A. Gold-magnetite nanocomposite materials formed via sonochemical methods. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008, 15, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavan, V.; Sivanand, P.S.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Koltypin, Y.; Gedanken, A. Catalytic aerobic oxidation of cycloalkanes with nanostructured amorphous metals and alloys. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 3521–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J.H.; Suslick, K.S. Applications of ultrasound to the synthesis of nanostructured materials. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 1039–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, A.V.; Vishnu Kamath, P.; Shivakumara, C. Order and disorder among the layered double hydroxides: Combined Rietveld and DIFFaX approach. Acta Cryst. B 2007, 63, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, R.E.; Krumeich, F.; Norby, P. Structural and microstructural changes during anion exchange of CoAl layered double hydroxides: An in situ X-ray powder diffraction study. J. Appl. Cryst. 2010, 43, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LDH Composition | a (Å) | c (Å) | d (Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co2Al–NO3 | Conventional co-precipitation followed by 4-h crystallization in a water bath | 3.063 | 26.732 | 8.911 |

| Co2Al–NO3 (sonication-assisted crystallization) | 2 min | 3.049 | 26.585 | 8.862 |

| 5 min | 3.071 | 26.579 | 8.860 | |

| 10 min | 3.054 | 26.513 | 8.838 | |

| Co2Al–CO3 | Standard anion-exchange (7 days) | 3.072 | 22.878 | 7.626 |

| Sonication-assisted exchange (7 min) | 3.070 | 22.831 | 7.610 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salak, A.N.; Vieira, D.E.L.; Lukienko, I.M.; Shapovalov, Y.O.; Fedorchenko, A.V.; Fertman, E.L.; Pashkevich, Y.G.; Babkin, R.Y.; Shilin, A.D.; Rubanik, V.V.; et al. High-Power Ultrasonic Synthesis and Magnetic-Field-Assisted Arrangement of Nanosized Crystallites of Cobalt-Containing Layered Double Hydroxides. ChemEngineering 2019, 3, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering3030062

Salak AN, Vieira DEL, Lukienko IM, Shapovalov YO, Fedorchenko AV, Fertman EL, Pashkevich YG, Babkin RY, Shilin AD, Rubanik VV, et al. High-Power Ultrasonic Synthesis and Magnetic-Field-Assisted Arrangement of Nanosized Crystallites of Cobalt-Containing Layered Double Hydroxides. ChemEngineering. 2019; 3(3):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering3030062

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalak, Andrei N., Daniel E. L. Vieira, Irina M. Lukienko, Yuriy O. Shapovalov, Alexey V. Fedorchenko, Elena L. Fertman, Yurii G. Pashkevich, Roman Yu. Babkin, Aleksandr D. Shilin, Vasili V. Rubanik, and et al. 2019. "High-Power Ultrasonic Synthesis and Magnetic-Field-Assisted Arrangement of Nanosized Crystallites of Cobalt-Containing Layered Double Hydroxides" ChemEngineering 3, no. 3: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering3030062