Effectiveness of Nurses’ Training in Identifying, Reporting and Handling Elderly Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

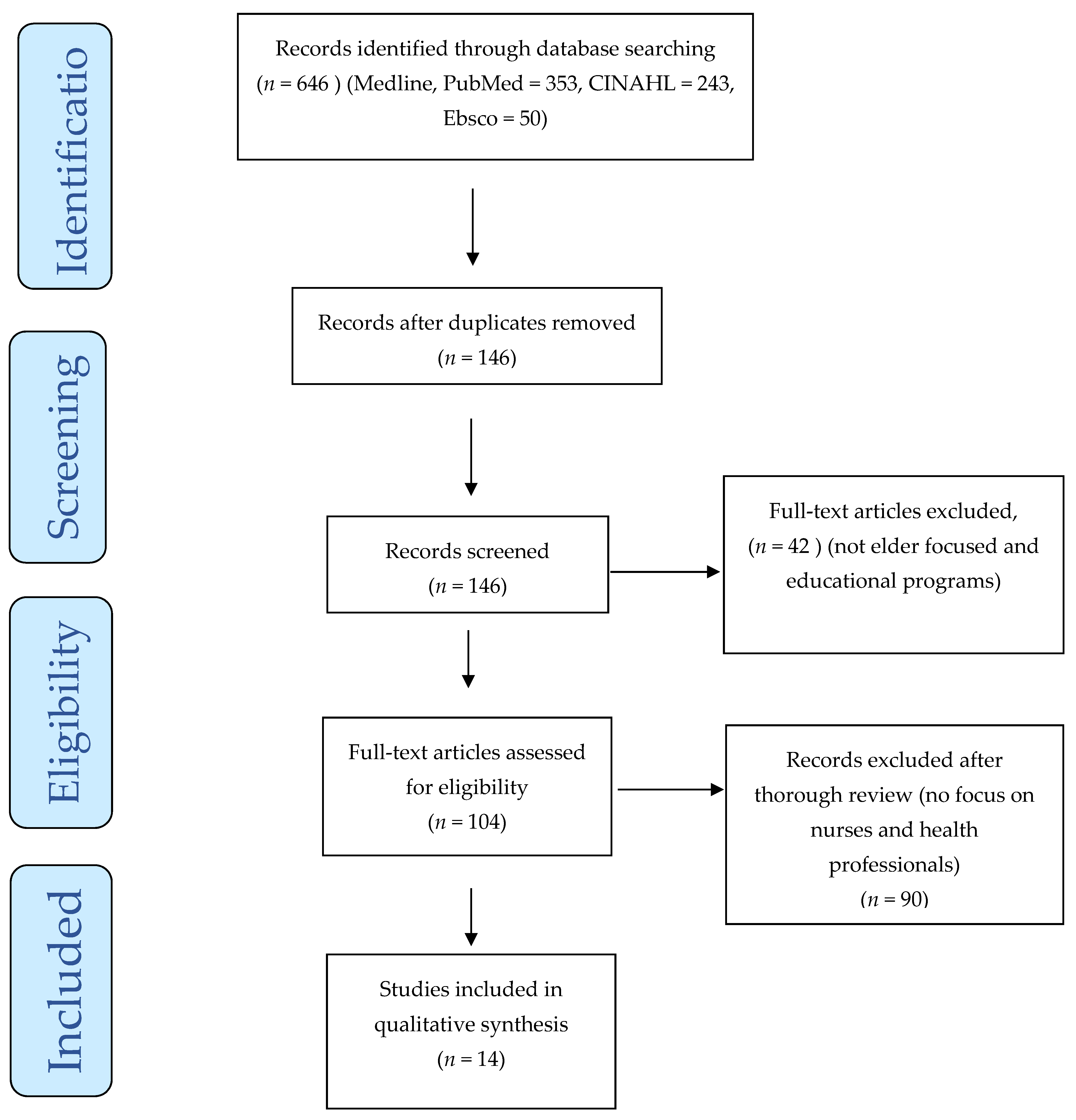

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Questions

- What is the effectiveness of a nurse training program in elder abuse management?

- What is the efficiency of different training methods about elder abuse?

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Critical Appraisal

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

4. PRISMA Flow Diagram

4.1. Knowledge Enhancement

4.2. Increased Identification of Elder Abuse

4.3. Reporting of Elder Abuse

4.4. Improved Competency in Dealing with Elder Abuse

4.5. Training Methods

5. Discussion

- Which trainings are more effective and why?

- What types of elder abuse require more focused training?

- How should the topic of elder abuse and mistreatment be integrated in nursing curricula? What is the effectiveness of such integration?

- What is the impact of nurses’ training on long-term reduction in the prevalence of elder abuse?

- What other changes need to be made structurally, politically, and culturally in order to significantly decrease the rates of elder abuse?

- Which other groups, apart from nurses, need to be trained in order to decrease prevalence of elder abuse?

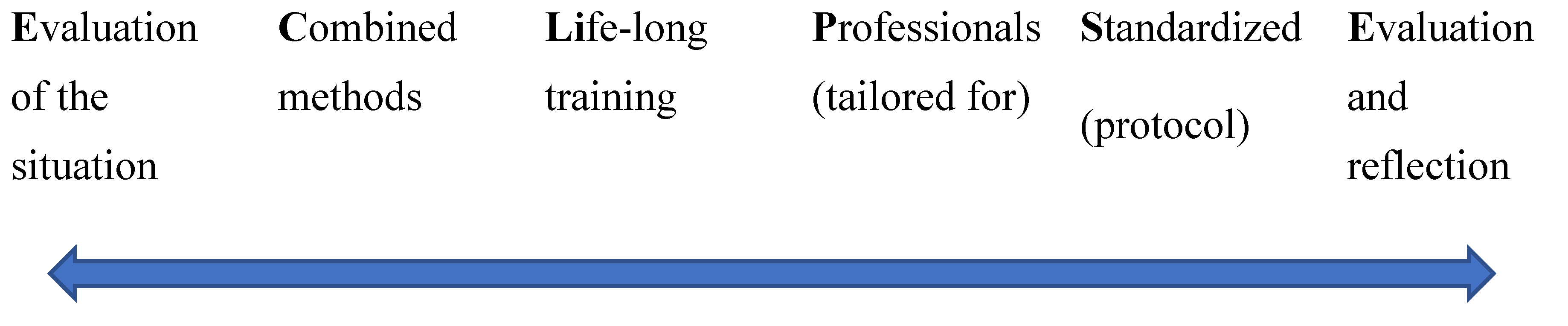

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dianati, M.; Azizi-Fini, I.; Oghalaee, Z.; Gilasi, H.; Savari, F. The Impacts of Nursing Staff Education on Perceived Abuse among Hospitalised Elderly People: A Filed Trail. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2021, 8, 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Elder Abuse. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/elder-abuse (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Mydin, M.H.F.; Yuen, W.C.; Hairi, M.N.N.; Hairi, M.F.; Ali, Z.; Aziz, A.S. Evaluating the Effectiveness of I-NEED Program: Improving Nurses’ Detection and Management of Elder Abuse and Neglect- A 6-Month Prospective Study. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, NP719–NP741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, T.E.M.; Bryan, L.J.; Thomas, L.K.; Pickens, L.S. Elder Abuse Education Using Standardized Patient Simulation in an Undergraduate Nursing Program. J. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 59, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, J.; Park, J. Educational needs related to elder abuse among undergraduate nursing students in Korea: An importance-performance analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 104, 104975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosa, D.S.; Mont, D.J. Development and Evaluation of an Elder Abuse Forensic Nurse Examiner e-Learning Curriculum. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yon, Y.; Mikton, C.R.; Gassoumis, Z.D.; Wilber, K.H. Elder Abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, P.; Yang, H.; Davies, M.; Gihooly, M.; Gilhooly, K.; Thompson, C. Identifying and enhancing risk thresholds in the detection of elder financial abuse: A signal detection analysis of professionals’ decision. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelotti, S.; Antone, D.E.; Ventrucci, C.; Mazzotti, C.M.; Salsi, G.; Dormi, A.; Ingravallo, F. Recognition of elder abuse by Italian nurses and nursing students: Evaluation by the Caregiving Scenario Questionnaire. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 2013, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooryanarayana, R.; Choo, W.Y.; Hairi, N.N.; Chinna, K.; Hairi, F.; Ali, Z.M.; Bulgiba, A. The prevalence and correlates of elder abuse and neglect in a rural community of Negeri Sembilan state: Baseline findings from The Malaysian Elder Mistreatment Project (MAESTRO), a population-based survey. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acierno, R.; Hernandez, M.A.; Amstadter, A.B.; Resnick, H.S.; Steve, K.; Muzzy, W.; Kilpatrick, D.G. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L. The mistreatment of older Canadians: Findings from the 2015 national prevalence study. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2018, 30, 176–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillemer, K.; Burnes, D.; Riffin, C.; Lachs, M.S. Elder Abuse: Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Prevention Strategies. Gerontologist 2016, 56 (Suppl. 2), S194–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, S.; Khanal, P.; Chalise, H.N. Elderly abuse experienced by older adults prior to living in old age homes in Kathmandu. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2018, 7, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, I.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, E. Geriatrics fact sheet in Korea 2018 from national statistics. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2019, 23, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, D.J.; Kosa, D.; Yang, R.; Solomon, S.; Macdonald, S. Determining the effectiveness of an Elder Abuse Nurse Examiner Curriculum: A pilot study. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 55, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, Z.E.C.; Ridenour, K.; Salaysay, Z.; Reyes-Gastelum, D.; Pierce, J.S. EATI Island- A virtual-reality based elder abuse and neglect educational intervention. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2017, 39, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.K.; Bachuwa, G.; Evans, J.; Jackson-Johnson, V. Assessing barriers to the identification of elder abuse and neglect: A community-wide survey of primary care physicians. J. Natl. Med. 2006, 98, 403–404. [Google Scholar]

- Corbi, G.; Grattagliano, I.; Sabbà, C.; Fiore, G.; Spina, S.; Ferrara, N.; Campobasso, C.P. Elder abuse: Perception and knowledge of the phenomenon by healthcare workers from two Italian hospitals. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2019, 14, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.; Koh, K.C. Factors Related to Korean Nurses’ Willingness to Report Suspected Elder Abuse. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012, 6, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Teresi, A.J.; Ramirez, M.; Ellis, J.; Silver, S.; Boratgis, G.; Kong, J.; Eimicke, P.J.; Pillemer, K.; Lachs, S.M. A staff intervention targeting resident-to-resident elder mistreatment (R-REM) in long-term care increased staff knowledge, recognition, and reporting: Results from a cluster-randomized trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhre, J.; Saga, S.; Maleal, W.; Ostasz, J.; Nakrem, S. Elder abuse and neglect: An overlooked patient safety issue. A focus group study of nursing home leaders’ perceptions of elder abuse and neglect. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71?gclid=CjwKCAjwmJeYBhAwEiwAXlg0AWNYlJ8pRgUFCmOvEjNf1VDc1v3ftG-Ex04RTJB-yxW-3N6mMDTfSRoCGLQQAvD_BwE (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Tufanaru, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Campbell, J.; Hopp, L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Estebsari, F.; Dastoorpoor, M.; Khanjani, N.; Khalifehkandi, R.Z.; Foroushani, R.A.; Aghababaeian, H.; Taghdisi, H. Design and implementation of an empowerment model to prevent elder abuse: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Interv. Ageing 2018, 13, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari, F.; Alipour, A.; Forokian, Z. The Effects of Education on Nurses’ Ability to Recognize Elder Abuse Induced by Family Members. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2020, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ejaz, K.F.; Rose, M.; Anetzberger, G. Development and implementation of online training modules on abuse, neglect, and exploitation. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2017, 29, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, K.; Kääriäinen, M. Content Analysis in Systematic Reviews. In The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wildemuth, B.M. Qualitative analysis of content. In Applications of Social Research Methods tomQuestions in Information and Library Science; Wildemuth, B., Ed.; Libraries Unlimited: Westport, CT, USA, 2009; pp. 308–319. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion | Primary research articles or chapters |

| Theses and dissertations | |

| Literature reviews and meta-analyses | |

| Conference research papers | |

| Studies of nurses’ trainings and elderly abuse Published in English Period of publication 2010–2022 | |

| Exclusion | Research articles, chapters, reviews, theses or dissertations, conference research papers which do not relate to nurses’ trainings and elderly abuse |

| Any of the above publications published before 2010 | |

| Published in languages other than English |

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomized Control Trials. | |||||||||||||

| Reference | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 |

| [21] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| [8] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| [26] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| [27] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| [3] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies. | |||||||||||||

| Reference | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | ||||

| [6] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| [1] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| [4] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| [16] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| [17] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| [28] | √ | √ | √ | No | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies. | |||||||||||||

| Reference | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | |||||

| [9] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| [5] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| [20] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Reference | Methodology | Sample | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [20] | Cross-Sectional studies | 365 nurses | The sample consisted of 359 female and 6 male nurses. 18.6% of nurses were not willing to report suspected elder abuse. Reason: 50.0% Considering it family matter due to Korean tradition influence not intervening in family discussion:

(SD ¼ 1.83) on a scale of 0 to 7. Nurses willing to report were trained and had knowledge on elder abuse law. The years of experience, knowledge on elder abuse, and perceived severity were significant predictors of willingness to report the case. The nurses with knowledge of elder abuse had 1.27 times higher the willingness to report the case. |

| [21] | Randomized control trial | 1405 residents 325 nurses | Staff on the experimental units received training and implementation protocols and Staff on the comparison units did not Experimental Group Knowledge: nursing staff’s gain in knowledge was evidenced for both Module 1 (p < 0.001) and Module 2 (p < 0.001) in that the total post-test scores for each module were significantly different (indicative of higher levels of knowledge) from the total pre-test scores. After training experimental group recognized and reported twice as many incidents as the control group. (6 times higher than the controlled group) Higher levels of recognition and documentation of resident-to-resident mistreatment (R-REM) were observed in the experimental group. At six months the recognition and reporting in the experimental group increased seven times higher. Additionally, 10 times higher in 12 months. The average reported events per resident per year was 0.35 in control group and 2.06 were reported from intervention group. |

| [9] | Cross-Sectional studies | 193 nursing students 76 nurses | Neglect was identified by 25% nurses and 20% of students. Locking someone at home was identified half of them (18 nurses, 39 nurses), majority labelled it as bad idea but did not recognise as abusive. Most of the nurses and student identified non-abusive strategies. Corelation between education and work experience was found. The nurses were able to recognise abusive strategies more accurately. This was seen in relation to their work experience and the education received. 74 nurses and 184 student received education on elder abuse, 88 nurses worked for elderly, 53 taught what to do when elder abuse was noticed, who identified abusive strategy of putting table on lap to limit the mobility of elderly. |

| [8] | Randomized control trial | Novice health and social care professionals Intervention—78 (Online web-based decision training Control = 76 (no training) | 154 novices made judgements of risk of abuse (“certainty of abuse”) on the same set of 43 scenarios that the experienced clinicians had judged. The experts mean’ certainty of abuse was higher than of novice pre-intervention in 28 scenarios. The experts have consistency in their detection. Detection of financial abuse the scores of the control and intervention Control Group: Pre-test—0.45 and post-test—0.55 Intervention Group: Pre-test—0.45 and post-test—0.71 Expert were more certain than the novice in detection of financial abuse (Mean 70.61 vs. 58.04). The intervention group mean score (64.84) than control group (61.41) post-test in certainty of identification. The intervention group were sensitivity in saying at risk for incident was not more than control group pretraining. Post-training, the intervention group were more sensitive in stating risk of abuse. |

| [28] | Quasi-experimental study | Nurse, social worker, counsellors, nurse practitioners. (453) | It was composed of three modules covering background, screening, and reporting abuse. Of 453 enrolees, 273 completed at least one module and 212 completed all three. Pre- and post-training surveys for each module were used to examine changes in the proportion of correct answers for each question, using the related-samples Cochran’s Q statistic. Module 1: Knowledge on background on abuse significantly increased. (4 question: correct pretraining vs. post-training

Correct pretraining vs. post-training

|

| [16] | Quasi-experimental study | from 18 SANEs. Sexual Assault nurse examiner | A 52-item pre- and post-training questionnaire was administered that assessed participants’ self-reported knowledge and perceived skills-based competence related to elder abuse care. A curriculum training evaluation survey was also delivered following the training. Overall, Knowledge: Self-reported knowledge/expertise on elder abuse increased (2.36 pre vs. 3.45 post). Knowledge and Skill-based Competence: Increase in all six domain- Older adults and abuse (3.53 vs. 4.61), Documentation, legislation, legal issues (2.70 vs. 4.17), Interview with older adults, caregiver, and other relevant contacts (3.40 vs. 4.24), Assessment (3.28 vs. 4.17), Medical and Forensic Examination (3.83 vs. 4.41), Case summary discharge plan, follow-up care (3.37 vs. 4.04). There was increase in knowledge on 49 items out of 52 post-training. |

| [17] | Quasi-experimental study | 39 nurses from the introductory 101 course a 36 staff participated in virtual-reality-based advanced training | After virtual-reality-based advanced training: Participants appreciated the interactive nature of the training, receiving feedback in real-time, debriefings focused on clinical reasoning and the QualCare Scale. Participants were usually able to obtain the required information. The decision level regarding whether to report potential Elder Abuse and Neglect (EA/N), decisions had 99% accuracy. About specific changes implemented in practice revealed participants implemented a variety of changes including being more thoughtful about: the implications of the living environment, probing more about resource distribution, more detailed assessment of nutrition and food access, and utilizing questions from the human rights assessment subscale to better understand the relationship dynamics |

| [26] | Randomized control trialG | 464 participants | The demographic characteristics between intervention and control group were similar. The frequency of knowledge of elder abuse was similar pre training in both control and intervention (113 vs. 177). The knowledge, self-efficacy, health promoting behaviours increased post-training in intervention group compared to control (220 vs. 108) In logistic model, post- training social support showed connection with intervention, health status. The intervention did not directly help to prevent the risk of elder abuse but helped with other variables to prevent it. |

| [3] | Randomized control trial | 203 primary-care nurses | Baseline knowledge on Elder Abuse and Neglect (EAN), Controlled—4.49 Intervention—4.66(lecture) 4.51(video) There was increase in Knowledge after intervention: Control—4.96 Intensive Training Program (ITP)—6.50 ITP+ - 6.44 Attitude: Control: 20.91 ITP: 22.61 ITP+: 23.00 Confidence Control: 19.10 ITP: 21.72 ITP+: 22.75 Post-intervention There was increase in the knowledge, attitude and confidence to intervene in EAN among participant of ITP and ITP+ group compared to controlled group |

| [4] | Quasi-experimental study | 119 students enrolled in the gerontology course were the participants | There was a significant difference in pre-test and post-test knowledge (4.71 vs. 6.02) and skills (3.87 vs. 4.52). Attitude even pre-test was 4.9 among students (max 5), so there was no space left for improvement. Training on how to identify, assess, and report elder abuse enhanced students learning. Lecture with M = 4.46, Simulation (M = 4.68), Debriefing (M = 4.68). There was comment space for students post-training, they stated that lecture, simulation, and debriefing increased their knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy in preventing, identifying, and advocating for victims of elder abuse. |

| [1] | Quasi-experimental study | 88 nurses were given training 431 elderly people were assessed with questionnaire | Characteristics: Mean age 71.68 years before and 73.33 years after interventions. The mean score on elder abuse was 29.16 before and 32.62 after which means that elder abuse occurrence was reduced. The highest subscale was scored by psychological abuse, which mean it was the lowest level of abuse among other type of abuse. The score of psychological abuse before intervention was 4.34 and 4.56 after intervention. The physical abuse before intervention 3.84 and 4.67 after intervention. (Identified more as it is more objective). Neglect was identified as least prevailed among others. Education reduced perceived abuse among hospitalised older adults |

| [27] | Randomized control trial | 120 nurses Intervention group—60 Controlled—60. Intervention—Received education via power point lectures, education booklets. | 21.7% participant experience at least one case of elder abuse (EA). 55.8% believed the EA reporting is not their responsibility. No significant difference in general characteristics. Baseline recognition ability score: controlled—224.9, intervention: 220.4. After intervention: Controlled 224.85, intervention255.96. After intervention, staff recognition skills increased. The highest score post intervention was related to physical component. Participants noted that elderly’s dependency on caregiver had high risk in occurrence of Elderly Abuse (EA) especially in case alcohol and drug dependency. There was slight decrease in score from 1 month to 3 month which suggest that continuing education is required. |

| [5] | Cross-Sectional studies | 324 nursing students | Characteristics, 90.3% female and rest male. 13.8% only received elder abuse education. 3.1% witnessed Elderly Abuse, 1.5 % psychological, 2.8% neglect, 2.8% reported. Level of importance on education was higher than of performance in elder abuse identification (4.29 vs. 3.08). Importance and performance-based score on educational topic: physical 4.49, psychological 4.47, understanding of physical an emotional change 4.1, human rights 4.40, neglect 4.43. Certain items have highest value in performance than in importance. |

| [6] | Quasi-experimental study | 54 nurses | Significant increase in expertise in caring for abused elderly after intervention Knowledge and competence score increase from Pre-M 3 to post Mean 4.4 on elder abuse care. Documentation, legal and legal issuers knowledge raised from 3.2 to 4.1 Initial assessment 3.6 vs. 4.6 Participant were satisfied with the curriculum: Clarity (90.6%), ability of material to engage and keep attention by 76.5%, Knowledge and management by 90.4%. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ranabhat, P.; Nikitara, M.; Latzourakis, E.; Constantinou, C.S. Effectiveness of Nurses’ Training in Identifying, Reporting and Handling Elderly Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7050108

Ranabhat P, Nikitara M, Latzourakis E, Constantinou CS. Effectiveness of Nurses’ Training in Identifying, Reporting and Handling Elderly Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review. Geriatrics. 2022; 7(5):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7050108

Chicago/Turabian StyleRanabhat, Pratibha, Monica Nikitara, Evangelos Latzourakis, and Costas S. Constantinou. 2022. "Effectiveness of Nurses’ Training in Identifying, Reporting and Handling Elderly Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review" Geriatrics 7, no. 5: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7050108

APA StyleRanabhat, P., Nikitara, M., Latzourakis, E., & Constantinou, C. S. (2022). Effectiveness of Nurses’ Training in Identifying, Reporting and Handling Elderly Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review. Geriatrics, 7(5), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7050108