Epidemiology and Screening of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Europe: A Scoping Review

Abstract

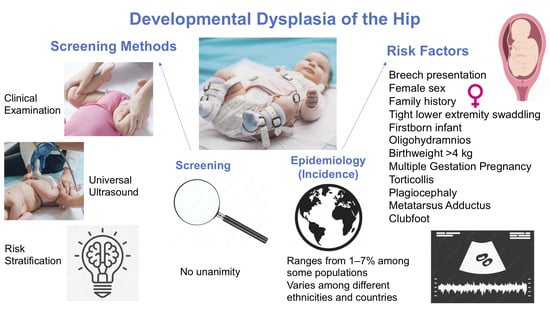

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological Studies

3.2. DDH Screening

| References | Focus of the Study | Country or Region | Time Period | Study Type | Objective | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perry DC, 1 November 2011 [31] | Association between clubfoot and DDH | UK | 2002–2008 | observational cohort | epidemiology | Among children with clubfoot and DDH, 5.9% will require treatment |

| Price et al., 1 June 2013 [32] | Evaluation of current screening practices; only two examinations: at birth and then at six to ten weeks of age | UK, Nottinghmam | 1990–2005 | retrospective review | screening | Established a final examination for DDH during the first six to nine months of life that would potentially prevent a significant increase in the presentation of DDH beyond walking age |

| Phelan et al., 1 June 2015 [33] | Incidence and treatment outcomes of DDH | Southest Ireland | 2009 | retrospective study | epidemiology | The incidence of DDH was estimated 6.73 per 1000 live births. The rate of open procedures was 1.08 per 1000 live births |

| Olsen et al., 1 February 2018 [16] | Evaluation of screening effectiveness when adding universal ultrasound hip examinations within three days of life | Norway, Kongsberg Hospital | 1998–2006 | screening | The treatment rate was doubled, without influencing the already low numbers of late cases | |

| O’Grady MJ, 1 June 2010 [34] | Current practices in Ireland; most units (84%) were dependent on radiographs at 4–6 months for imaging hips; only two units primarily used ultrasound (10.5%) | Ireland | 2006 | prospective and retrospective study | screening | Selective ultrasound and examination by an experienced clinician are not widely practiced |

| Talbot CL, 1 September 2013 [35] | Evaluation of current screening methods; the Newborn and Infant Physical Examination (NIPE) programme in the UK recommends selective ultrasound screening for at-risk infants (breech presentation and family history) | UK | 2008–2013 | observational, longitudinal cohort study | screening | The risk of DDH in males referred with risk factors but clinically stable hips was found to be low |

| Wenger D, 1 December 2020 [29] | Evaluation of the addition of secondary screening for hip dislocations | Sweeden | 2000–2009 | retrospective analysis | screening | Secondary screening at 6–8 weeks, 6 months, and 10–12 months of age has decreased the age of late diagnosis in half of children that were not diagnosed through primary screening |

| Biedermann R, 1 October 2018 [36] | Incidence study | Austria | 1998–2014 | prospective follow-up | epidemiology | Incidence of DDH: 8 per 1000 live births, treatment rate: 1% |

| Geertsema D, 1 August 2019 [37] | Does delayed radiological hip screening at five months (versus ultrasound at 3 months) result in a higher incidence of persistent developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) at 18 months? | Northern Ireland | 2011–2017 | a prospective observational study | screening | No significant difference in incidence or severity of persistent DDH at 18 months between the two screening groups |

| Treiber M, 1 January 2008 [38] | To assess the results of the general screening program of newborns’ hips in Maribor between 1997 and 2005 in comparison to results from 1985 for the same region | Maribor | 1997–2005 | retrospective analysis | screening | Universal US in neonates led to a reduction in the overall treatment rate |

| Milligan DJ, 1 April 2020 [39] | To assess the quality of services for DDH in Northern Ireland (neonates with a positive screening examination should undergo ultrasound scanning) | Musgrave Park Hospital, Belfast, UK | prospective observational study | screening | Conformity to the regional neonate hip screening protocols led to reduction in the rates of open procedures and in the number of pelvic x-rays in infants | |

| Maxwell Sl, 27 April 2002 [9] | Evaluation of screening methods in Northern Ireland | Northern Ireland | 1983–1987 | comparative retrospective study | epidemiology | The true incidence of DDH still remains unknown |

| Salut C, 1 November 2011 [26] | To identify the value of US screening for DDH. Systematic US evaluation of the hips using the Couture technique was performed at 1 month with all girls with a normal physical examination at birth over a 1-year period. | Limoges, France | 2009 | retrospective study | screening | A total of 74 abnormal hips undetected during the initial clinical evaluation in girls without risk factors were detected and treated |

| von Kries R, 1 February 2012 [20] | To assess the effectiveness of general ultrasound screening to prevent first operative procedures of the hip | Munich, Germany | 1996–2001 | case-control study | screening | Universal ultrasound reduces the rate of operative procedures for DDH |

| Barr LV, 1 January 2013 [5] | Do multiple births lead to a higher incidence of DDH and is there a need for selective US? | Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge, UK | 2004–2008 | retrrospective study | epidemiology | Multiple births were not found to be a risk factor for DDH |

| von Kries R, 6 December 2003 [21] | Evaluation of current screening practices (universal ultrasound screening at first 6 weeks of life) | Germany | 1996–2001 | retrospective study | screening | US seems to prevent the many cases that require open surgery for DDH |

| Reidy M, 1 October 2019 [19] | Evaluation of current screening practices (neonate hip examination at 6–8 weeks of life) | UK | 2006–2011 | longitudinal observational study | screening | Four out of five children with DDH were not identified at 6–8 weeks. This screening method in its current form is not reliable |

| Jashi R, 12 May 2017 [40] | What is the prevalence of hip dysplasia among relatives with family history of hip dysplasia operated with periacetabular osteotomy (PAO)? | Denmark | 1998–2014 | cross sectional study | epidemiology | Females seemed to have an increased familial prevalence of hip dysplasia in comparison to males, but the increased prevalence was not statistically significant |

| McAllister et al., 1 November 2018 [41] | To calculate the risk of open surgery for DDH for infants up to 3 years old before and after the improved DDH detection services (Ortolani and Barlow tests shortly after birth vs. increased use of US) | Scotland | 1997/98–2010/11 | retrospective cohort study | epidemiology | The improved DDH detection services have reduced the number operative procedures for DDH from April 2005 and after |

| Davies R, 1 April 2020 [42] | Evaluation of current screening methods (clinical examination of the hips at 6–8 weeks) | Royal Blackburn Hospital, England | 1996–2010 | observational cohort | screening | 6- to 8-week clinical hip assessments yielded sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive, and negative predictive values of 16.7%, 99.8%, 3.5%, and 100.0%, respectively |

| Colta RC, 1 January 2016 [43] | Analysis of risk factors for DDH | Bucharest, Romania | 2013–2015 | retrospective study | epidemiology | Increased gestational age and increased birthweight were associated with a higher risk for DDH |

| Laborie Lb., 1 September 2013 [17] | Evaluation of the addition of universal or selective ultrasound screening for DDH | Norway | 2011–2013 | randomized control trial | screening | Selective and universal ultrasound screening led to a nonsignificant reduction in the rate of late diagnoses |

| Muresan S,1 January 2019 [27] | Epidemiological study in Romania | Romania | 2016 | retrospective study | screening epidemiology | The most frequently diagnosed stage was type IA, and the rarest stage was III. The incidence of type III hip dysplasia was 0.2% |

| Peterlein CD, 1 June 2014 [44] | Epidemiological study in Marburg | Franziskus Hospital, Marburg | 1985–2009 | retrospective study | epidemiology | Breech presentation was significantly correlated with decentering and eccentric hips. Treatment of hip type II a according to Graf was inconsistent over time. Inexperienced physicians recommended therapeutic interventions more frequently |

| Broadhurst et al., 1 March 2019 [30] | Epidemiology study | Southampton Children’s Hospital, UK | 1990–2016 | observational study | epidemiology | The incidence of the late DDH diagnosis was 1.28 per 1000 live births and 71.1% of cases were detected in children between one and two years of age, with a female-to-male ratio of 4.2:1 |

| Elbourne D, 21 December 2002 [25] | To assess the effectiveness and net cost of US compared with clinical examination alone | UK | 1994–1998 | randomised control trial | other | Utilizing ultrasound for infants with clinically detected hip instability lowered the need for abduction splinting |

| Lambeek AF et al., 1 April 2013 [4] | To assess the effect of a successful external cephalic version on the incidence of DDH requiring treatment in singleton breech presentation at term | The Netherlands | 2006–2009 | observational cohort study | epidemiology | Achieving a successful external cephalic version is linked to a reduced occurrence of DDH, but a notable proportion of children born following a successful external cephalic version still exhibit DDH |

| Kamath S et al., 1 May 2007 [45] | To determine if employing ultrasound for screening infants with risk factors has resulted in a decrease in late DDH | Whiston Hospital, UK | 1992–2001 | epidemiology | The annual incidence from 1992 to 1996 was reported to be 0.84, and from 1997 to 2001, it was 0.57 per 1000 births. The decline was not significant | |

| Laborie et al., 1 April 2014 [17] | To assess the use of selective US as part of the screening programme | Bergen, Norway | 1991–2006 | prospective survey | screening epidemiology | Selective and universal ultrasound screening led to a nonsignificant reduction in the rate of late diagnosis in comparison to clinical examination |

| Čustović S et al., 1 August 2018 [18] | What is the relationship between the clinical sign of limited abduction of the hips and DDH? | Tuzla, Sweeden | 2011–2012 | prevalence study | screening epidemiology | Limited abduction of the hips had a positive predictive value 40.3% and a negative predictive value of 80.4% for DDH. Limitation of the abduction of the hip is an important sign of DDH |

| Giannakopoulou C, 1 January 2002 [11] | Epidemiology of DDH in Crete | Crete, Greece | 1996–2000 | retrospective study | epidemiology | The incidence of DDH was estimated to be 10.83 per 1000, higher than in the rest of Greece. Medical and family history and clinical examination contribute to the diagnosis of hip instability |

| Burger BJ, 22 December 1990 [46] | Epidemiology of DDH in The Netherlands | The Netherlands | 1971–1979 | prospective follow-up study | screening epidemiology | The percentage of missed dislocations of hips during screening was 0.02%. Dysplasia was detected at 5 months in 15% of infants with a positive family history and a negative Barlow test |

| Wenger D, 1 October 2013 [29] | X-ray findings at 1 year of age in children who received early treatment for neonatal instability of the hips | 2002–2007 | cohort study | screening epidemiology | The incidence of instability of hips in newborns was 7 per 1000 live births, and the referral rate was 15 per 1000. Girls were 82% of cases | |

| Lewis K et al., 1 November 1999 [22] | What is the use of static US in DDH screening? | Morison Hospital, Wales | 1988–1992 | prospective study | screening | Simple static ultrasound is an effective screening test for DDH that should be applied to the general population |

| Lange AE, 16 March 2017 [47] | Compare the incidence of DDH between preterm and full-term babies | Germany | 2002–2008 | retrospective study | epidemiology | Preterm infants with gestational age < 36 weeks have a decreased risk of DDH |

| Rühmann O et al., 1999 [13] | The contribution of risk factors to the development of DDH | Germany | 1987–1995 | retrospective study | epidemiology | A higher rate of treatment needed was associated with family history of DDH, breech presentation, and female sex |

| Paton RW et al. 2005 [48] | The contribution of risk factors in screening with US | England, UK | 1992–2002 | prospective study | other | Risk factors and/or clinical instability of the hip was present in 7.4% of newborns, and 31% of the newborns with clinical instability had an associated risk factor. Family history, breech presentation, and foot deformity were the principal risk factors |

| Rosendahl K et al., 2 September 1996 [14] | Estimation of prevalence based on US diagnosis | Bergen, Norway | 1988–1990 | retrospective study | epidemiology | More females than males had minor and major dysplasia. Having a first-degree relative with DDH was found to be a risk factor. Breech presentation at birth was an important risk factor only for females |

| Jones D, 1 August 1977 [49] | Evaluation of current screening methods | England, UK | 1968–1972 | screening | Clinical examination of neonate hips is not an adequate screening tool; repeated examinations should be performed | |

| Czeizel A et al., 1 November 1974 [10] | Incidence of DDH in Hungary | Budapest, Hungary | 1970–1972 | retrospective study | epidemiology | The incidence was estimated to be 28–71 per 1000 live births |

| Dunn PM et al., 1 May 1985 [50] | Comparison between the frequency of early and late diagnosis | Bristol, United Kingdom | 1970–1979 | retrospective study | epidemiology | The frequency of DDH diagnosis among neonates was 1.9%. The frequency of DDH diagnosis after the neonatal period ranged from 0.04 to 0.1% |

| Merk H et al., 1 October 1999 [51] | Evaluation of diagnostic strategy for DDH (clinical and sonographic screening examination) | Germany | 1984–1995 | retrospective study | epidemiology | Among the 4177 observed newborns, 39 cases of congenital dislocation of the hip joint in 27 children were found. After 12 months, a complete healing rate of 95 percent was exhibited with the functional management strategy |

| Zenios M et al., 1 October 2000 [52] | Impact of selective US screening on the late diagnosis of DDH in the Salford region | Hope Hospital, UK | 1991–1995 | retrospective study | screening | The incidence of late diagnosis was not reduced when compared with two previous cohorts at the same center |

| Sionek A et al., 1 March 2018 [53] | Effect of gender on the development of DDH | Warsaw, Poland | 2008 | retrospective study | screening | Gender seems to be a significant risk factor. Type IIa hips were more common in females |

| Boere-Boonekamp MM, 1 February 1998 [54] | To assess the validity of a standardized screening protocol for DDH in neonates (physical examination and possible referal) | Hengelo, The Netherlands | 1992–1993 | prospective studies | screening | The validity of this screening protocol for DDH is low. The addition of US to current screening protocols needs further evaluation |

| Krismer M et al., 1 January 1996 [55] | The contribution of US screening and treatment with a Pavlik harness to the incidence of DDH. | Austria | 1979–1988 | prospective studies | screening epidemiology | A significantly decreased dislocation rate was detected, suggesting that early use of US is valuable in the early detection of hip dislocation |

| Hindrraker et al., 1994 [56] | The contribution of intra-uterine factors to the hip instability of neonates (NIH) | Norway | 1970–1988 | regression analysis | epidemiology | The prevalence of NHI at birth was 0.9%: (0.6% in boys, 1.4% in girls). Among children born in breech presentation, the rate was 4.4% |

| Lennox IA et al., 1 January 1993 [57] | Evaluation of screening methods for DDH | Scotland | 1980–1989 | retrospective study | screening | Many dislocations have not been detected during newborn examinations (this referred to 0.13% of live births); 0.08% of live births required operative treatment |

| Falliner et al., 1998 [58] | Diagnosis and therapeutic management of DDH during the last seven years | Germany | 1991–1997 | retrospective study | Screening | Approximately 81% of newborns with clinical hip instability during birth obtained a sonographic DDH diagnosis. In 38% of them, it was possible to diagnose DDH within the first week of life |

| Engesaeter IØ et al., 1 June 2008 [24] | Does neonate hip instability increase the risk of total hip replacement (THR) in young adulthood? | 1967–2004 | retrospective study | other | Hip instability of neonates increases the risk of THR in young adulthood, although only 8% of those who had a THR due to hip dysplasia had unstable hips as neoantes. The authors conclude that clinical examination alone is insufficient as a screening method | |

| Günther KP et al., 1 November 1998 [23] | Evaluation of universal ultrasound screening for DDH in Germany since 1996 | Germany | 05/1997–10/1998 | cross-sectional study | screening epidemiology | US was performed too late and not at all in 35% of cases |

| Kramer et al., 1 January 1988 [59] | Evaluation of risk factors; does a positive family history contribute to DDH development? | Norway | 1964–1984 | comparative study | epidemiology | Having a first-degree relative with DDH resulted in a 10-fold increase in the DDH risk on average |

| Kramer et al., 1 January 1987 [60] | Evaluation of screening methods (with Barlow and Ortolani tests) | Norway | 1964–1983 | retrospective study | epidemiology | Breech presentation and early parity situation were linked to a higher risk of DDH. Neonatal screening programs in Norway may have demonstrated limited accuracy |

| Garvey M et al., 1 September 1992 [28] | Implementation of a screening programme for infants at four months of age who were clinically normal at neonatal examination but were considered to be ‘at risk’ for congenital dislocation (family history, breech presentation, persistent click) | Dublin | 1986–1988 | prospective pilot study | screening | Performing a hip radiography four months after birth significantly enhances neonatal screening for infants who face a higher risk of hip-related issues |

| Heikkilä E, 1 April 1984 [61] | Epidemiology of DDH in Finland | Uusima, Finland | 1966–1975 | epidemiology | The incidence was calculated to be 0.68% of liveborns | |

| Husum et al., February 2019 [62] | Assessment of the pubo-femoral distance (PFD) in the lateral position as an indicator for unstable DDH | Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark | 2013–2016 | epidemiology | A PFD value above 4.4 mm was 100% sensitive and 93% specific for the detection of unstable DDH | |

| Krikler SJ, 1 September 1992 [15] | Evaluation of screening methods; only clinical tests on new-born infants | Royal Orthopaedic Hospital, Birmingham|England | 1980–1990 | comparative study | screening | Screening for all neonates at birth and follow-ups of children at high risk for DDH by an appropriate and experienced team with a well-designed protocol are recommended |

| Godward et al., 18 April 1998 [63] | Evaluation of screening methods in the UK (universal clinical screening) | England | 1993–1994 | retrospective study | epidemiology | The percentage of neonates requiring an operative procedure for congenital dislocation of the hip in the UK was similar to that reported before screening was introduced |

| Ferris et al., 1 April 1997 [64] | Evaluation of protective factors against DDH | Ireland | 1983–1995 | retrospective study | other | Neonates in the supine or lateral position and the contribution of hip screening were correlated to a reduction in the incidence of late diagnoses of CDH. X-rays should be performed at 6 months old for infants with risk factors |

| Czeizel et al., 1 June 1975 [65] | Evaluation of risk factors (two family studies) | Hungary | 1962–1967 | retrospective study | epidemiology | The incidence of DDH was calculated 28.7 per 1000 live births. (In total, 523 infants required treatment from the total of 18,219 live births registered.) The impact of genetic predisposition could not be confirmed |

| Clausen et al., 1988 [66] | Epidemiological correlations between birth presentation, mode of delivery, and DDH | Denmark | 1973–1986 | retrospective observational study | epidemiology | Breech presentation was associated with DDH—13.3% of the neonates in this presentation were later diagnosed with DDH. No significant correlation between the mode of delivery and DDH diagnosis |

| Bernard et al., 1987 [67] | Evaluation of screening methods | West Midlands, England | 1977–1983 | retrospective observational study | screening | Repeated screening of high-risk newborns by physiotherapists effectively decreased the frequency of late DDH diagnoses |

| Bjerkreim et al., 1 May 1987 [68] | Late diagnosis of DDH in Norway during 1970–1974 | Norway | 1970–1974 | retrospective observational study | epidemiology | Late DDH diagnosis may be associated with progressing dysplasia of the hip during the first twelve months of life |

| Macnnicol, 1990 [69] | Results of a 25-year screening program for neonatal hip instability | Edinburgh, Scotland | 1962–1985 | prospective study | screening | The frequency of late DDH diagnoses was 0.5 per 1000 live births when the examinations were carried out by junior physicians. Examination by or together with senior physicians is recommended to decrease the rates of late DDH diagnosis |

| Finlay et al., 1967 [70] | DDH epidemiology in Northern Ireland | Northern Ireland, United Kingdom | 1962–1967 | prospective observational study | epidemiology | The frequency of DDH diagnosis with the Barlow test was approximately 0.4% (60 cases among 14,594 infants) |

| Βeckman et al.,1977 [12] | DDH epidemiology in Nothern Sweeden | Sweden | 1960–1973 | prospective study | epidemiology | The incidence of neonatally diagnosed with congenital dislocation of the hip (CDH) ranged between 10.0, 7.1, and 3.5 per one thousand in different centers |

| Czeizel et al., 1972 [10] | DDH epidemiology in Hungary | Hungary | 1962–1967 | retrospective study | epidemiology | Among 108,966 infants, DDH incidence was 27.53 per 1000 live births; 72.4% of the diagnoses were made within the first 6 months of life |

| Konijnendijk et al., 2021 [71] | Evaluation of risk factors for DDH | The Netherlands | 2021 | cross-sectional study | epidemiology, risk factors | Breech presentation after gestational week 37.0 was associated with a more than threefold higher DDH risk |

| Guindani, 2021 [72] | Screening for DDH during the COVID-19 lockdown | Italy | 2019–2020 | retrospective study | screening | DDH-USS was the only screening in newborns during lockdown. The study observed a 22% decrease in DDH screening rates; 29% of DDH diagnoses were delayed, made at a mean age of 114 days |

| Koob et al., 2020 [73] | Epidemiology, risk factors | Central Europe | 2013–2016 | retrospective study | epidemiology, risk factors | Prematurity was inversely associated with DDH. Premature birth at gestational week 31 had the lower DDH incidence |

| Gunther et al., 1993 [74] | Epidemiology, risk factors | United Kingdom | 1988–1990 | retrospective study | epidemiology, risk factors | Multigravidae and similarly multiparous women had a statistically significantly reduced risk of having a baby with CDH. Babies born by Caesarean section or in breech position had an increased risk of CDH (statistically significant). Cases were more likely to have a family history of CDH than subjects who were screened but found to be normal |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nandhagopal, T.; De Cicco, F.L. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, S.L.; Mubarak, S.J.; Wenger, D.R. Developmental hip dysplasia and dislocation: Part II. Instr. Course Lect. 2004, 53, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, B.A.; Segal, L.S.; Section on Orthopaedics; Otsuka, N.Y.; Schwend, R.M.; Ganley, T.J.; Herman, M.J.; Hyman, J.E.; Shaw, B.A.; Smith, B.G. Evaluation and Referral for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Infants. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20163107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambeek, A.; De Hundt, M.; Vlemmix, F.; Akerboom, B.; Bais, J.; Papatsonis, D.; Mol, B.; Kok, M. Risk of developmental dysplasia of the hip in breech presentation: The effect of successful external cephalic version. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 120, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, L.V.; Rehm, A. Should all twins and multiple births undergo ultrasound examination for developmental dysplasia of the hip? A retrospective study of 990 multiple births. Bone Jt. J. 2013, 95-B, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bache, C.E.; Clegg, J.; Herron, M. Risk factors for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: Ultrasonographic Findings in the Neonatal Period. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 2002, 11, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorter, D.; Hong, T.; Osborn, D.A. Cochrane Review: Screening programmes for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborn infants. Evid.-Based Child Health Cochrane Rev. J. 2013, 8, 11–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, S.L. Quality improvement report: Clinical screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in Northern Ireland. BMJ 2002, 324, 1031–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeizel, A.; Szentpetery, J.; Kellermann, M. Incidence of congenital dislocation of the hip in Hungary. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1974, 28, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulou, C.; Aligizakis, A.; Korakaki, E.; Velivasakis, E.; Hatzidaki, E.; Manoura, A.; Bakataki, A.; Hadjipavlou, A. Neonatal screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip on the maternity wards in Crete, Greece. correlation to risk factors. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 29, 148–152. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, L.; Lemperg, R.; Nordström, M. Congenital dislocation of the hip joint in Northern Sweden: Neonatal diagnosis and need for orthopaedic treatment. Clin. Genet. 1977, 11, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rühmann, O.; Lazović, D.; Bouklas, P.; Gossé, F.; Franke, J. Sonographisches Hüftgelenk—Screening bei Neugeborenen. Klin. Pädiatr. 1999, 211, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosendahl, K.; Markestad, T.; Lie, R. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. A population-based comparison of ultrasound and clinical findings. Acta Paediatr. 1996, 85, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krikler, S.; Dwyer, N. Comparison of results of two approaches to hip screening in infants. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1992, 74-B, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.F.; Blom, H.C.; Rosendahl, K. Introducing universal ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip doubled the treatment rate. Acta Paediatr. 2018, 107, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laborie, L.B.; Engesæter, I.Ø.; Lehmann, T.G.; Eastwood, D.M.; Engesæter, L.B.; Rosendahl, K. Screening Strategies for Hip Dysplasia: Long-term Outcome of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čustović, S.; Šadić, S.; Vujadinović, A.; Hrustić, A.; Jašarević, M.; Čustović, A.; Krupić, F. The predictive value of the clinical sign of limited hip abduction for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). Med. Glas. 2018, 15, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, M.; Collins, C.; MacLean, J.G.B.; Campbell, D. Examining the effectiveness of examination at 6–8 weeks for developmental dysplasia: Testing the safety net. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 953–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Kries, R.; Ihme, N.; Altenhofen, L.; Niethard, F.U.; Krauspe, R.; Rückinger, S. General Ultrasound Screening Reduces the Rate of First Operative Procedures for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: A Case-Control Study. J. Pediatr. 2012, 160, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Kries, R.; Ihme, N.; Oberle, D.; Lorani, A.; Stark, R.; Altenhofen, L.; Niethard, F.U. Effect of ultrasound screening on the rate of first operative procedures for developmental hip dysplasia in Germany. Lancet 2003, 362, 1883–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Jones, D.A.; Powell, N. Ultrasound and neonatal hip screening: The five-year results of a prospective study in high-risk babies. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1999, 19, 760–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, K.; Stoll, S.; Schmitz, A.; Niethard, F.; Altenhofen, L.; Melzer, C.H.; Kries, R. Erste Ergebnisse aus der Evaluationsstudie des sonographischen Hüftscreenings in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland*. Z. Orthop. Grenzgeb. 2008, 136, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engesæter, I.Ø.; Lie, S.A.; Lehmann, T.G.; Furnes, O.; Vollset, S.E.; Engesæter, L.B. Neonatal hip instability and risk of total hip replacement in young adulthood. Acta Orthop. 2008, 79, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbourne, D.; Dezateux, C.; Arthur, R.; Clarke, N.; Gray, A.; King, A.; Quinn, A.; Gardner, F.; Russell, G. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of developmental hip dysplasia (UK Hip Trial): Clinical and economic results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002, 360, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salut, C.; Moriau, D.; Pascaud, E.; Layré, B.; Peyrou, P.; Maubon, A. Résultats initiaux d’une expérience de dépistage échographique systématique de la luxation congénitale de hanche chez la fille. J. Radiol. 2011, 92, 920–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mureşan, S.; Mărginean, M.O.; Voidăzan, S.; Vlasa, I.; Sîntean, I. Musculoskeletal ultrasound: A useful tool for diagnosis of hip developmental dysplasia: One single-center experience. Medicine 2019, 98, e14081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, M.; Donoghue, V.; Gorman, W.; O’Brien, N.; Murphy, J. Radiographic screening at four months of infants at risk for congenital hip dislocation. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1992, 74-B, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenger, D.; Tiderius, C.J.; Düppe, H. Estimated effect of secondary screening for hip dislocation. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020, 105, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhurst, C.; Rhodes, A.M.L.; Harper, P.; Perry, D.C.; Clarke, N.M.P.; Aarvold, A. What is the incidence of late detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip in England?: A 26-year national study of children diagnosed after the age of one. Bone Jt. J. 2019, 101-B, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.C.; Tawfiq, S.M.; Roche, A.; Shariff, R.; Garg, N.K.; James, L.A.; Sampath, J.; Bruce, C.E. The association between clubfoot and developmental dysplasia of the hip. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2010, 92-B, 1586–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.R.; Dove, R.; Hunter, J.B. Current screening recommendations for developmental dysplasia of the hip may lead to an increase in open reduction. Bone Jt. J. 2013, 95-B, 846–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, N.; Thoren, J.; Fox, C.; O’Daly, B.J.; O’Beirne, J. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: Incidence and treatment outcomes in the Southeast of Ireland. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 1971- 2015, 184, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Grady, M.J.; Mujtaba, G.; Hanaghan, J.; Gallagher, D. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: Current practices in Ireland. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 179, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, C.L.; Paton, R.W. Screening of selected risk factors in developmental dysplasia of the hip: An observational study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedermann, R.; Riccabona, J.; Giesinger, J.M.; Brunner, A.; Liebensteiner, M.; Wansch, J.; Dammerer, D.; Nogler, M. Results of universal ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: A Prospective Follow-Up of 28 092 Consecutive Infants. Bone Jt. J. 2018, 100-B, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geertsema, D.; Meinardi, J.E.; Kempink, D.R.J.; Fiocco, M.; van de Sande, M.A.J. Screening program for neonates at risk for developmental dysplasia of the hip: Comparing first radiographic evaluation at five months with the standard twelve week ultrasound. A prospective cross-sectional cohort study. Int. Orthop. 2019, 43, 1933–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treiber, M.; Tomažič, T.; Tekauc-Golob, A.; Žolger, J.; Korpar, B.; Burja, S.; Takač, I.; Sikošek, A. Ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in the newborn: A population-based study in the Maribor region, 1997–2005. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2008, 120, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milligan, D.J.; Cosgrove, A.P. Monitoring of a hip surveillance programme protects infants from radiation and surgical intervention. Bone Jt. J. 2020, 102-B, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jashi, R.E.; Gustafson, M.B.; Jakobsen, M.B.; Lautrup, C.; Hertz, J.M.; Søballe, K.; Mechlenburg, I. The Association between Gender and Familial Prevalence of Hip Dysplasia in Danish Patients. HIP Int. 2017, 27, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.A.; Morling, J.R.; Fischbacher, C.M.; Reidy, M.; Murray, A.; Wood, R. Enhanced detection services for developmental dysplasia of the hip in Scottish children, 1997–2013. Arch. Dis. Child. 2018, 103, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.; Talbot, C.; Paton, R. Evaluation of primary care 6- to 8-week hip check for diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of the hip: A 15-year observational cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 70, e230–e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colta, R.C.; Stoicanescu, C.; Nicolae, M.; Oros, S.; Burnei, G. Hip dysplasia screening—Epidemiological data from Valcea County. J. Med. Life. 2016, 9, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peterlein, C.; Penner, T.; Schmitt, J.; Fuchs-Winkelmann, S.; Fölsch, C. Sonografisches Screening der Neugeborenenhüfte am Universitätsklinikum Marburg—Eine Langzeitanalyse. Z. Für Orthop. Unfallchirurgie 2014, 152, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamath, S.; Mehdi, A.; Wilson, N.; Duncan, R. The lack of evidence of the effect of selective ultrasound screening on the incidence of late developmental dysplasia of the hip in the Greater Glasgow Region. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 2007, 16, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, B.J.; Bos, C.F.A.; Rozing, P.M.; Obermann, W.M.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Burger, J.D. Neonatal screening and staggered early treatment for congenital dislocation or dysplasia of the hip. Lancet 1990, 336, 1549–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, A.E.; Lange, J.; Ittermann, T.; Napp, M.; Krueger, P.-C.; Bahlmann, H.; Kasch, R.; Heckmann, M. Population-based study of the incidence of congenital hip dysplasia in preterm infants from the Survey of Neonates in Pomerania (SNiP). BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, R.W. Screening for hip abnormality in the neonate. Early Hum. Dev. 2005, 81, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D. An assessment of the value of examination of the hip in the newborn. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1977, 59-B, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, P.M.; Evans, R.E.; Thearle, M.J.; Griffiths, H.E.; Witherow, P.J. Congenital dislocation of the hip: Early and late diagnosis and management compared. Arch. Dis. Child. 1985, 60, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merk, H.; Mahlfeld, K.; Wissel, H.; Kayser, R. Die angeborene Hüftluxation im sonographischen Verlauf—Häufigkeit, Diagnostik und Behandlungskonzept. Klin. Pädiatr. 1999, 211, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenios, M.; Wilson, B.; Galasko, C.S.B. The Effect of Selective Ultrasound Screening on Late Presenting DDH. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 2000, 9, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sionek, A.; Czubak, J.; Kornacka, M.; Grabowski, B. Evaluation of risk factors in developmental dysplasia of the hip in children from multiple pregnancies: Results of hip ultrasonography using Graf’s method. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2008, 10, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boere-Boonekamp, M.M.; Kerkhoff, T.H.; Schuil, P.B.; Zielhuis, G.A. Early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip in The Netherlands: The validity of a standardized assessment protocol in infants. Am. J. Public Health 1998, 88, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krismer, M.; Klestil, T.; Morscher, M.; Eggl, H. The effect of ultrasonographic screening on the incidence of developmental dislocation of the hip. Int. Orthop. 1996, 20, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinderaker, T.; Daltveit, A.K.; Irgens, L.M.; Udén, A.; Reikeräs, O. The impact of intra-uterine factors on neonatal hip instability. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1994, 65, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennox, I.; McLauchlan, J.; Murali, R. Failures of screening and management of congenital dislocation of the hip. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1993, 75-B, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falliner, A.; Hahne, H.-J.; Hassenpflug, J. Verlaufskontrollen und sonographisch gesteuerte Frühbehandlung der Hüftgelenksdysplasie. Z. Orthop. Grenzgeb. 2008, 136, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.A.; Berg, K.; Nance, W.E. Familial aggregation of congenital dislocation of the hip in a Norwegian population. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1988, 41, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.A.; Berg, K.; Nance, W.E. The Effect of Perinatal Screening in Norway on The Magnitude of Noninherited Risk Factors for Congenital Dislocation of the Hip. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1987, 125, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, E. Congenital dislocation of the hip in Finland: An epidemiologic analysis of 1035 cases. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1984, 55, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husum, H.-C.; Hellfritzsch, M.B.; Hardgrib, N.; Møller-Madsen, B.; Rahbek, O. Suggestion for new 4.4 mm pubo-femoral distance cut-off value for hip instability in lateral position during DDH screening. Acta Orthop. 2019, 90, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godward, S.; Dezateux, C. Surgery for congenital dislocation of the hip in the UK as a measure of outcome of screening. Lancet 1998, 351, 1149–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, H.; Ryan, C.A.; McGuinness, A. Decline in the incidence of late diagnosed congenital dislocation of the hip. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 1997, 166, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czeizel, A.; Szentpétery, J.; Tusnády, G.; Vizkelety, T. Two family studies on congenital dislocation of the hip after early orthopaedic screening Hungary. J. Med. Genet. 1975, 12, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clausen, I.; Nielsen, K.T. Breech position, delivery route and congenital hip dislocation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1988, 67, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, A.A.; O’Hara, J.N.; Bazin, S.; Humby, B.; Jarrett, R.; Dwyer, N.S. An Improved Screening System for the Early Detection of Congenital Dislocation of the Hip. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1987, 7, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerkreim, I.; Årseth, P.H.; Palmén, K. Congenital Dislocation of the Hip in Norway Late Diagnosis Cdh in the Years 1970 to 1974. Acta Paediatr. 1978, 67, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnicol, M. Results of a 25-year screening programme for neonatal hip instability. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1990, 72-B, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, H.V.L.; Maudsley, R.H.; Busfield, P.I. Dislocatable hip and dislocated hip in the newborn infant. BMJ 1967, 4, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnendijk, A.; Vrugteveen, E.; Voorthuis, B.; Boere-Boonekamp, M. Association between timing and duration of breech presentation during pregnancy and developmental dysplasia of the hip: A case-control study. J. Child Health Care 2023, 27, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindani, N.; De Pellegrin, M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip screening during the lockdown for COVID-19: Experience from Northern Italy. J. Child. Orthop. 2021, 15, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koob, S.; Garbe, W.; Bornemann, R.; Ploeger, M.M.; Scheidt, S.; Gathen, M.; Placzek, R. Is Prematurity a Protective Factor Against Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip? A Retrospective Analysis of 660 Newborns. Ultraschall Med. Eur. J. Ultrasound. 2022, 43, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, A.; Smith, S.J.; Maynard, P.V.; Beaver, M.W.; Chilvers, C.E.D. A case-control study of congenital hip dislocation. Public Health 1993, 107, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahan, S.T.; Katz, J.N.; Kim, Y.-J. To screen or not to screen? A decision analysis of the utility of screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2009, 91, 1705–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilsdonk, I.; Witbreuk, M.; Van Der Woude, H.-J. Ultrasound of the neonatal hip as a screening tool for DDH: How to screen and differences in screening programs between European countries. J. Ultrason. 2021, 21, e147–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, A.; Aarvold, A. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: Current UK practice and controversies. Orthop. Trauma. 2022, 36, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine; American College of Radiology. AIUM practice guideline for the performance of an ultrasound examination for detection and assessment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. J. Ultrasound Med. Off. J. Am. Inst. Ultrasound Med. 2009, 28, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.M.; Manara, J.; Chokotho, L.; Harrison, W.J. Back-carrying infants to prevent developmental hip dysplasia and its sequelae: Is a new public health initiative needed? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2015, 35, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidelman, M.; Chezar, A.; Bialik, V. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip Incidence in Ethiopian Jews Revisited: 7-Year Prospective Study. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 2002, 11, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den, H.; Ito, J.; Kokaze, A. Epidemiology of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: Analysis of Japanese National Database. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 33, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.H.; Eid, M.A.; Chow, W.; To, M.K. Screening for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Hong Kong. J. Orthop. Surg. 2011, 19, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loder, R.T.; Skopelja, E.N. The Epidemiology and Demographics of Hip Dysplasia. ISRN Orthop. 2011, 2011, 238607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Preventive health care, 2001 update: Screening and management of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. J. Assoc. Medicale Can. 2001, 164, 1669–1677. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laskaratou, E.D.; Eleftheriades, A.; Sperelakis, I.; Trygonis, N.; Panagopoulos, P.; Tosounidis, T.H.; Dimitriou, R. Epidemiology and Screening of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Europe: A Scoping Review. Reports 2024, 7, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports7010010

Laskaratou ED, Eleftheriades A, Sperelakis I, Trygonis N, Panagopoulos P, Tosounidis TH, Dimitriou R. Epidemiology and Screening of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Europe: A Scoping Review. Reports. 2024; 7(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports7010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaskaratou, Emmanuela Dionysia, Anna Eleftheriades, Ioannis Sperelakis, Nikolaos Trygonis, Periklis Panagopoulos, Theodoros H. Tosounidis, and Rozalia Dimitriou. 2024. "Epidemiology and Screening of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Europe: A Scoping Review" Reports 7, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports7010010