A Composite Tool for Forecasting El Niño: The Case of the 2023–2024 Event

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Natural Time Analysis of SOI Values

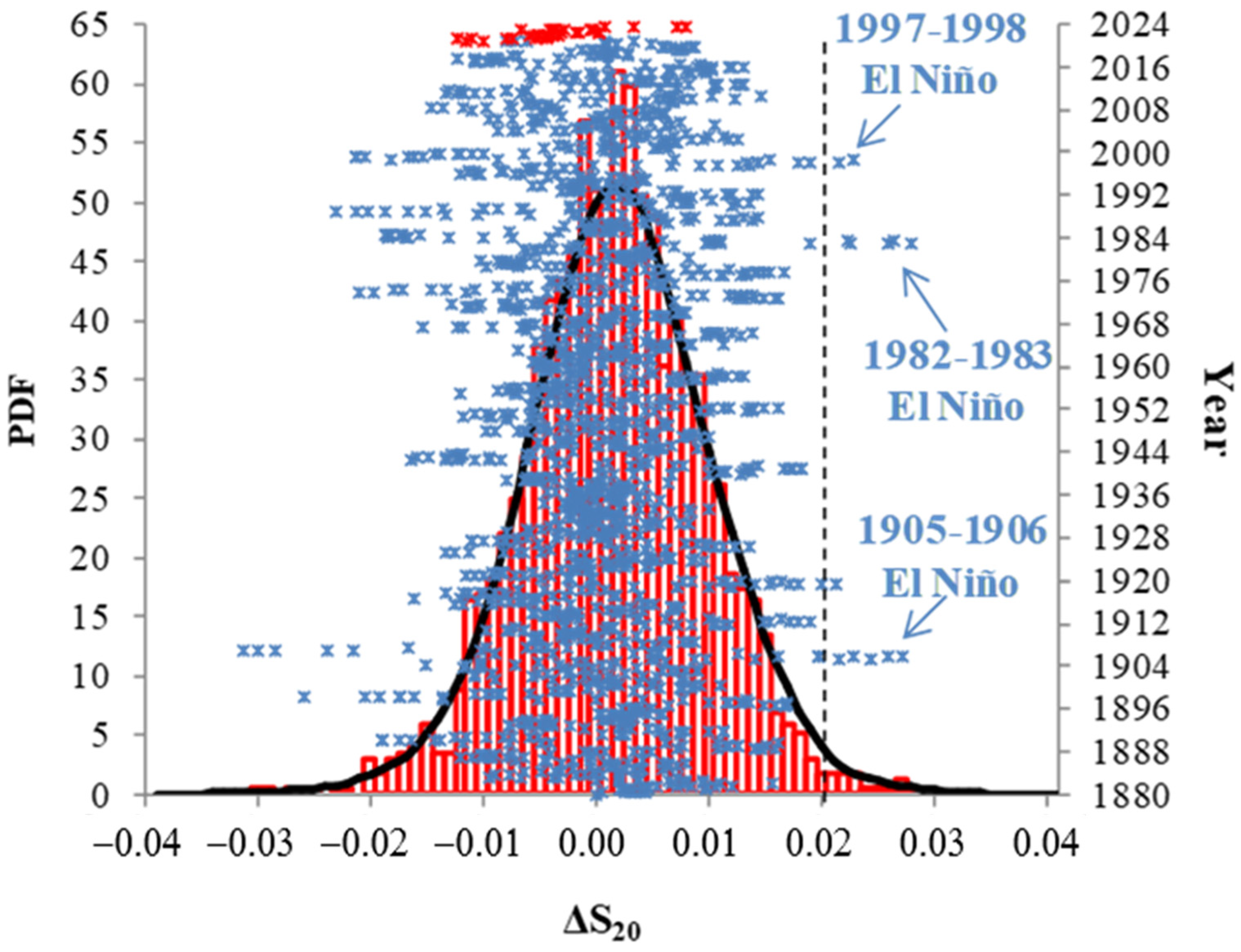

2.2. Estimation of the Probability Density Function of Δ

2.3. The Modified Natural Time Analysis Method for Nowcasting ONI Anomalies

3. Results and Discussion

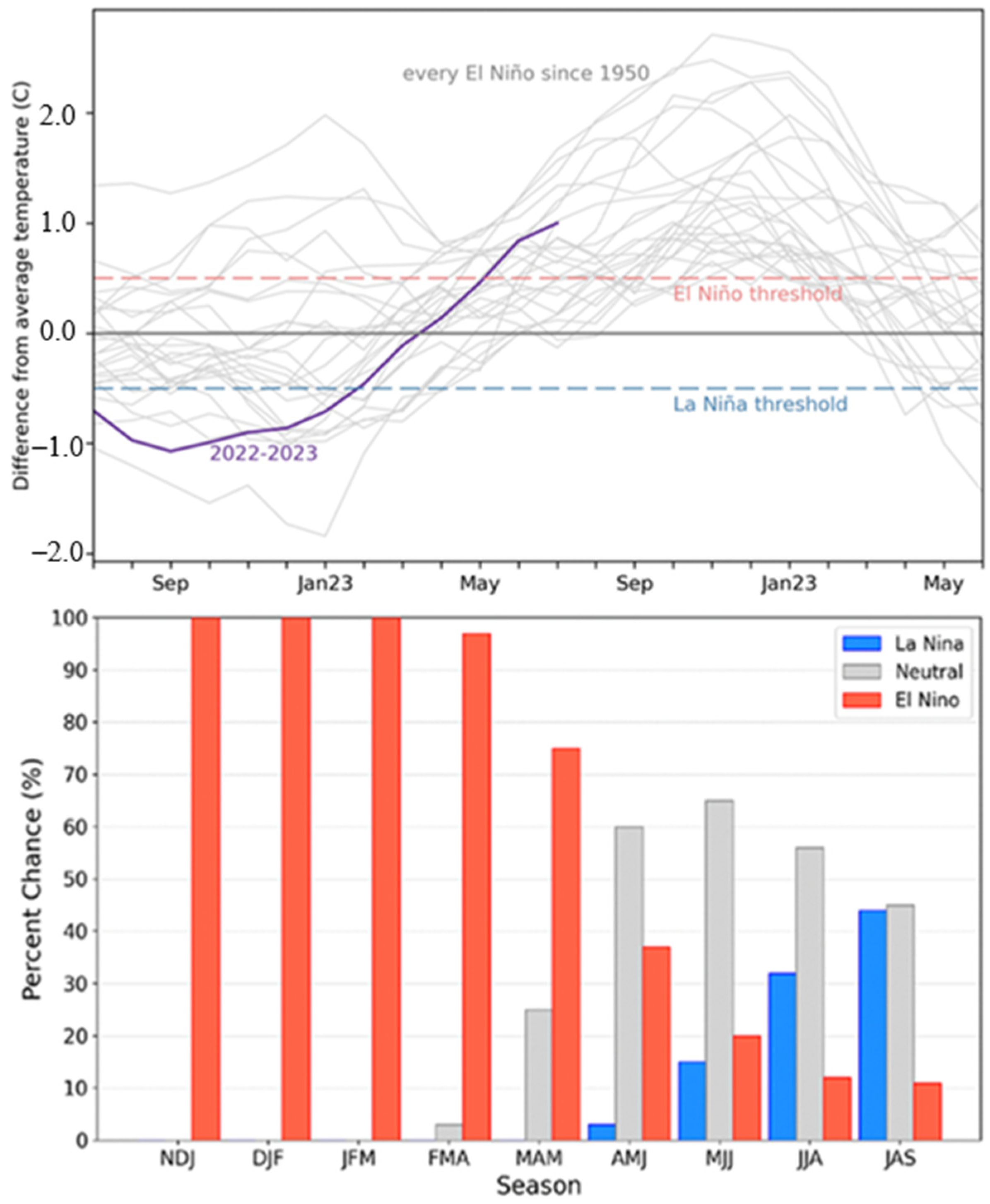

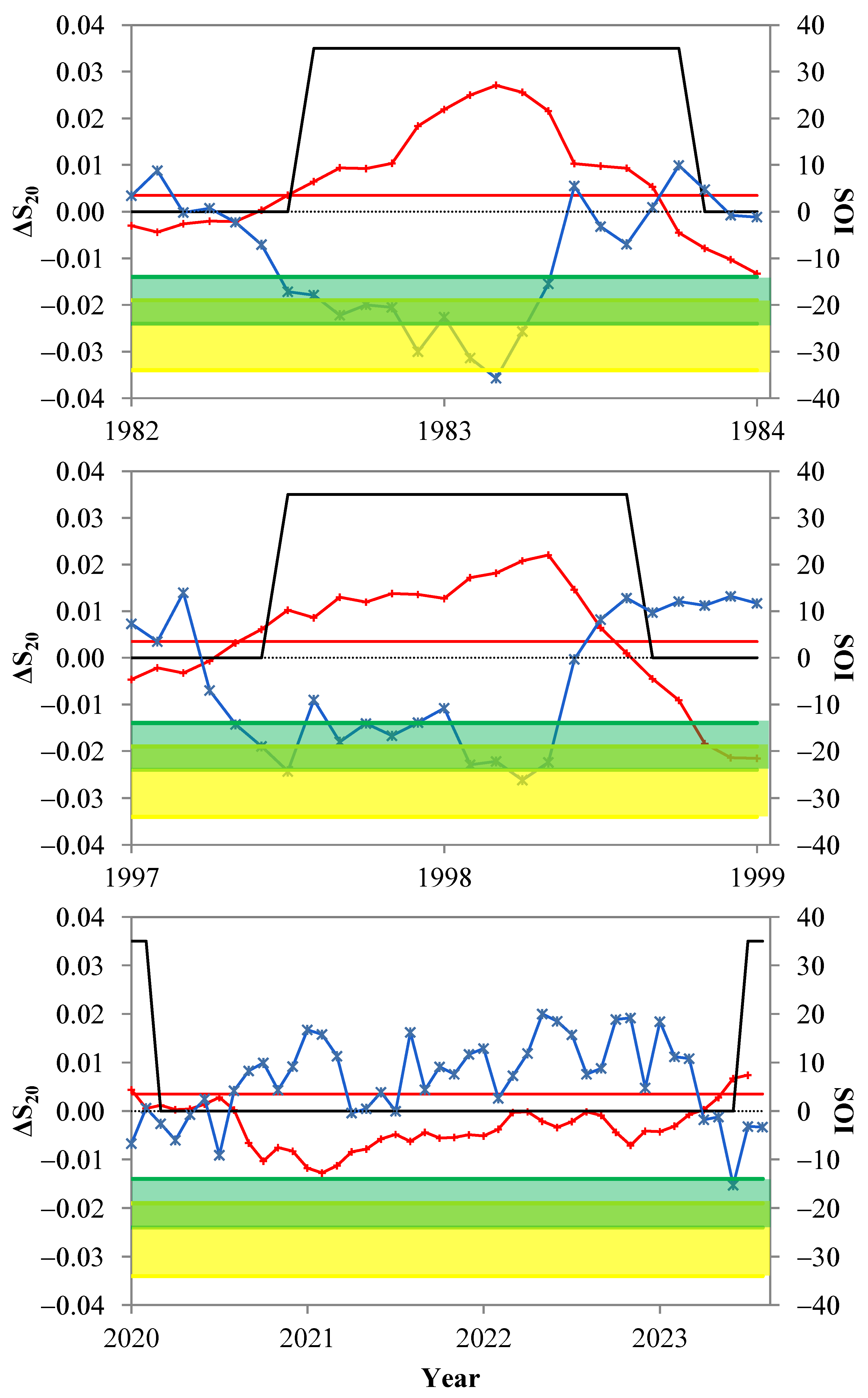

3.1. Experience Gained from Forecasting Previous Major El Niño Events as a Guide for Forecasting the 2023–2024 El Niño Using the ‘Natural Time Analysis”

3.2. On the Progress of the 2023–2024 El Niño Event Using the ‘Natural Time Analysis”

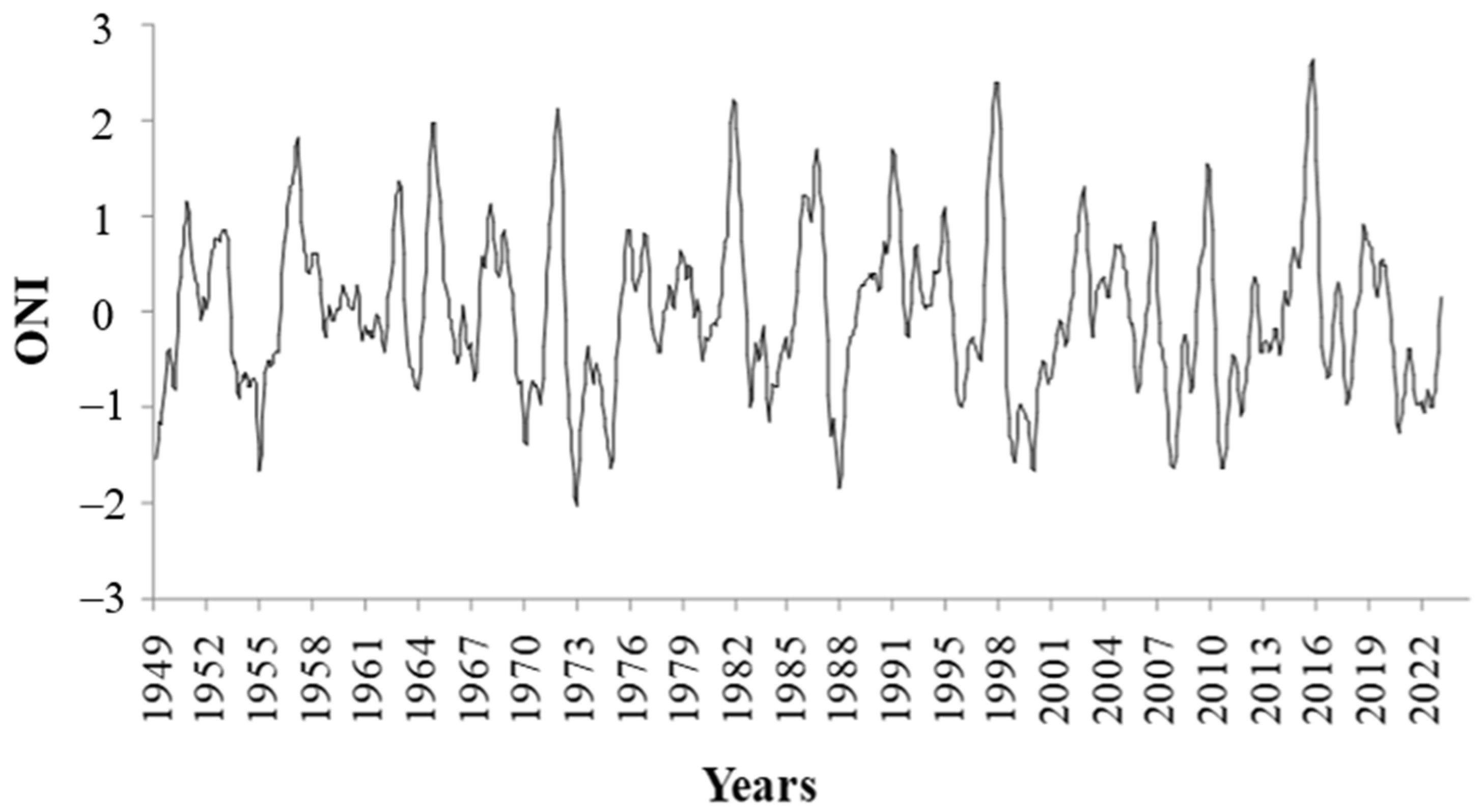

3.3. Forecasting El Niño Events Using the “Modified Natural Time Analysis” Applied to ONI

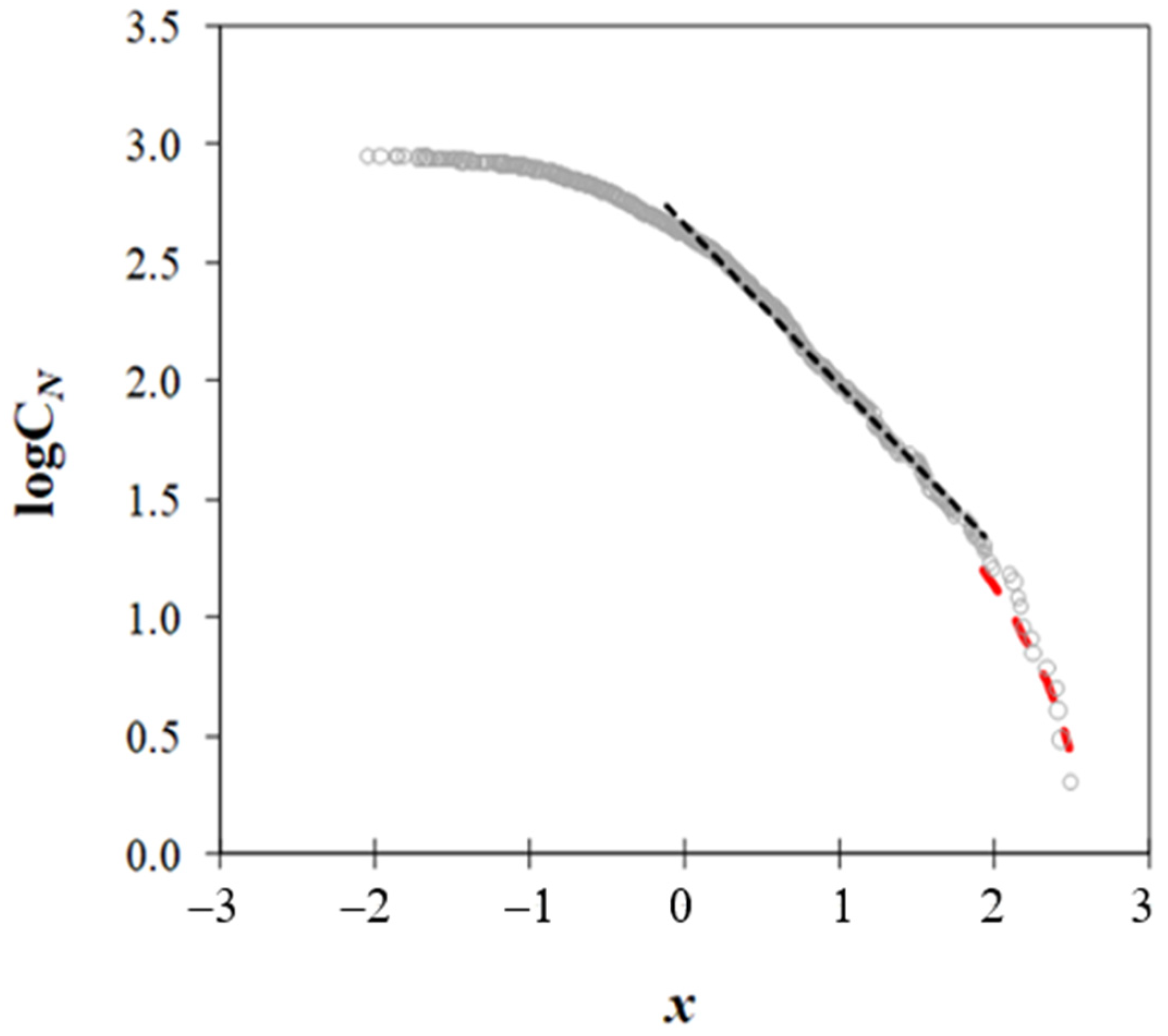

- (1)

- We plot the logarithm of the cumulative number (CN), see Section 2.3, of the ONI observations, equal to or above a certain x-value versus the x magnitude (Figure 7). For high ONI values, regression analysis reveals a statistically significant linear fit between logCN and x. The best linear fit is achieved for the range (−0.11, 1.93):

- (2)

- (3)

- To fit ONI values above rollover (i.e., x ≥ 1.93), we use an upper-truncated GR model developed by [38]where the values a0 and a1 are derived from Equation (4) and xmax = 2.72 is chosen to obtain the most accurate approximation.

- (4)

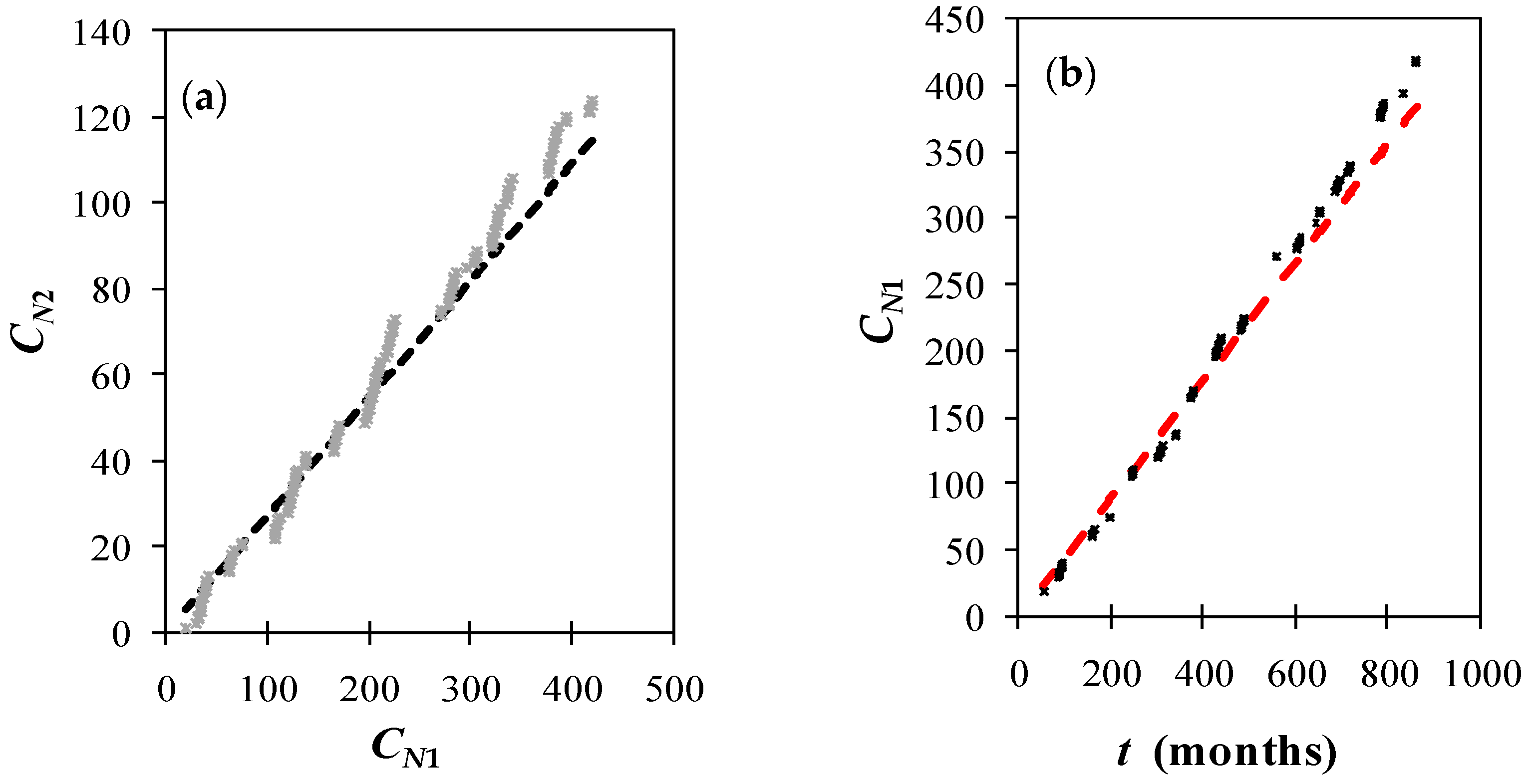

- Next, we use the M-NTA (see Section 2.3) to study the exceptional events in the time series of ONI anomalies. The x1 value is chosen as the average of the ONI dataset (i.e., −0.003), while the value x2 = 0.826 corresponds to the mean increased by the standard deviation of the dataset.The above-mentioned technique allows us to precisely test the accuracy of the GR fit by examining whether two values with a constant difference x2 − x1 have a constant ratio:where a0 is estimated from Equation (4) and CN1, CN2 is the cumulative number of ONI values with magnitude x ≥ x1 and x ≥ x2, respectively.

- (5)

- Indeed, we plot the pairs in Figure 8a, and an almost perfect linear fit (with A = and R2 = 0.97), thus confirming the accuracy of the GR-fit.

- (6)

- The NTA is also used to forecast the frequency of upcoming extreme ONI events, x2, by relying on the estimated average occurrence rate of the lowest ONI values, x1.

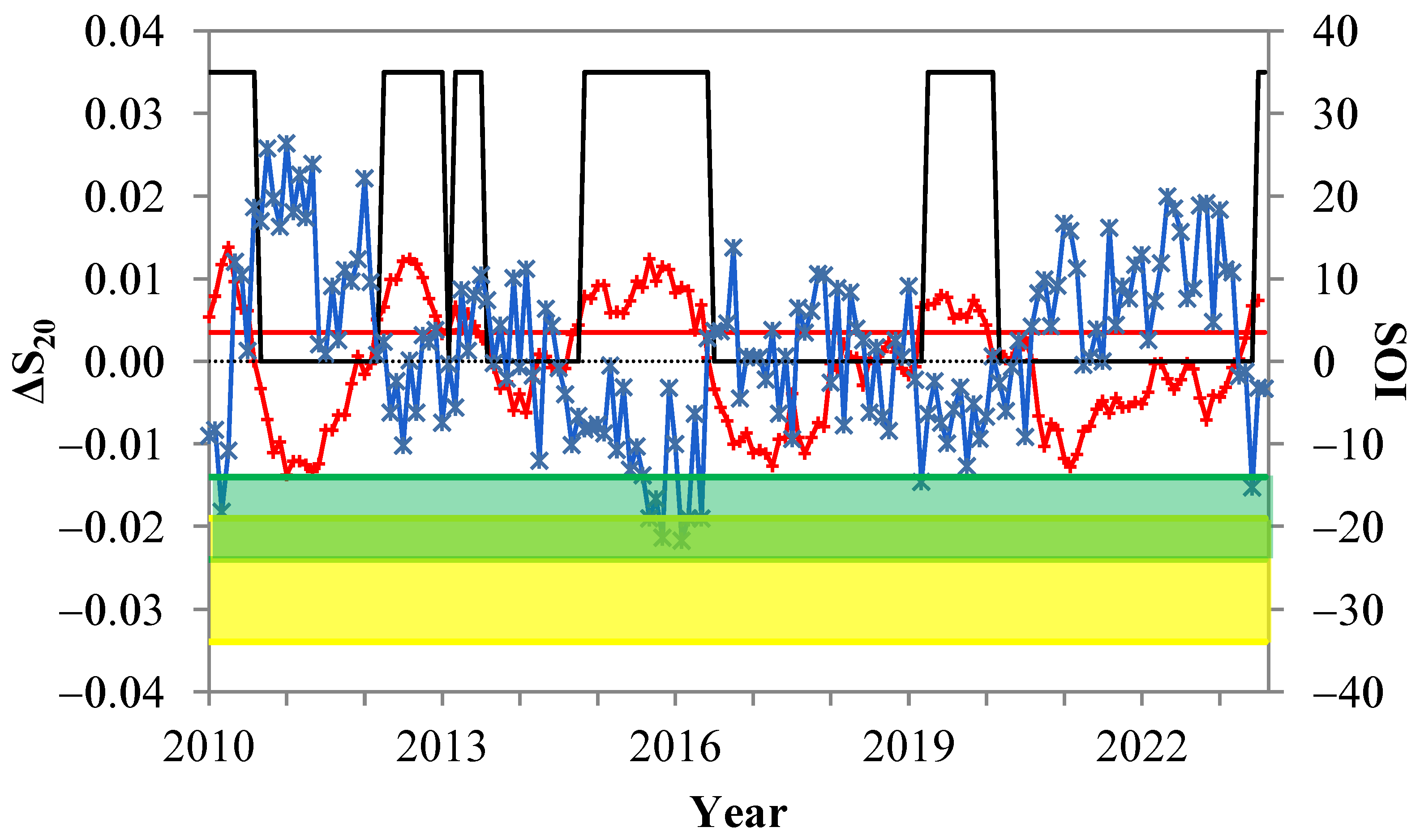

3.4. Forecasting El Niño Events Using the “Modified Natural Time Analysis” Applied to SOI

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Forecasting analysis performed by both NTA and M-NTA verified that the 2015–2016 El Niño was characterized as a “moderate to strong” event and not “one of the strongest on record”, as various forecasting reports of that period claimed.

- (2)

- The SOI time series during the period January 2021–July 2023 shows a variance that doesn’t foreshadow a strong 2023–2024 El Niño. Furthermore, the variation of entropy change in natural time during the 2023–2024 El Niño is less pronounced compared to the corresponding ones during past El Niño events. Finally, according to the probability density function of the ΔS_20 dataset, all the values during January 2021–July 2023 remain below the threshold m + s, where m (s) is the mean (standard deviation) of the dataset.

- (3)

- The M-NTA model appears to adequately estimate the interevent time from 1982 to 1997, two years that correspond to exceptional ONI values of the overall time series. The estimated time of the intermediate event between 1997 and 2016 is estimated to be (17.4, 26.1) years. The average recurrence time of the ONI extremes observed in 2015 was found to be between (18.9, 127.6) years.

- (4)

- Regarding the intensity of the ongoing 2023–2024 El Niño event, an ONI value of 2.64 occurred only in 2015 (moderate to strong El Niño), and the model predicts a recurrence period of over 85 years. So, it is unlikely to reappear in 2023. Instead, values from 2.14 to 2.40 coming from 1997 or 2016 may appear.

- (5)

- The extremely low SOI values observed in the last three strong ENSO events do not appear to be related to the ongoing ENSO event (2023–2024). On the other hand, the January 1983 SOI value could be related to the 2015–2016 ENSO, while the February 1983 SOI value is expected to affect years after 2038. The above-mentioned analytical tools may be applied to paleoclimatic data to predict extreme environmental phenomena that may lead to severe ecological impacts [31].

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walker, G.T.; Bliss, E.W. World Weather V. Mem. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1932, 4, 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Power, S.B.; Kociuba, G. The impact of global warming on the Southern Oscillation Index. Clim. Dyn. 2011, 37, 1745–1754. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00382-010-0951-7 (accessed on 10 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Rasmusson, E.M.; Carpenter, T.H. Variations in tropical sea surface temperature and surface wind fields associated with the Southern Oscillation/El Niño. Mon. Weather Rev. 1982, 110, 354–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troup, A.J. The Southern Oscillation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1965, 91, 490–506. Available online: https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/qj.49709139009 (accessed on 10 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Yun, K.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Timmermann, A.; Stein, K.; Stuecker, M.F.; Fyfe, J.C.; Chung, E.S. Increasing ENSO–rainfall variability due to changes in future tropical temperature–rainfall relationship. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelin, J.D.; Latif, M. El Nino dynamics. Phys. Today 1998, 51, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Ng, B.; Geng, T.; Jia, F.; Wu, L.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Gan, B.; Yang, K.; Santoso, A.; et al. Anthropogenic impacts on twentieth-century ENSO variability changes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sah, S.; Singh, R. The 2023-24 El Niño event and its possible global consequences on food security with emphasis on India. Food Sec. 2023, 15, 1431–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubilava, D.; Abdolrahimi, M. The El Niño Impact on Maize Yields Is Amplified in Lower Income Teleconnected Countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 054008. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab0cd0/meta (accessed on 10 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Glantz, M.H.; Ramirez, I.J. Reviewing the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) to Enhance Societal Readiness for El Niño’s Impacts. Int. J. Disaster Risk. Sci. 2020, 11, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurdek-Bas, R.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Harrison, H.B.; Zenger, K.R.; van Herwerden, L. The El Niño Southern Oscillation drives multidirectional inter-reef larval connectivity in the Great Barrier Reef. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanke, H.R.; Azizi, M.; Asadipour, E.; Barati, M. Climate Changes and Vector-borne Diseases with an Emphasis on Parasitic Diseases: A Narrative Review. Health Emerg. Disasters Quart. 2023, 8, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A. El Niño May Break a Record and Reshape Weather around the Globe. Scientific American. 21 June 2023. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/el-nino-may-break-a-record-and-reshape-weather-around-the-globe/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Yin, J.; Xu, J.; Xue, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Ren, Y. Evaluating the impacts of El Niño events on a marine bay ecosystem based on selected ecological network indicators. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 144205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, R.T.; Chavez, F.P. Biological Consequences of El Nino. Science 1983, 222, 1203–1210. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.222.4629.1203 (accessed on 10 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- WMO. El Niño/La Niña Updates. 2022. Available online: https://public.wmo.int/en/our-mandate/climate/el-ni%C3%B1ola-ni%C3%B1a-update (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Hamlington, B.D.; Willis, J.K.; Vinogradova, N. The emerging golden age of satellite altimetry to prepare humanity for rising seas. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2023EF003673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omid, A. Advances and challenges in climate modeling. Clim. Chang. 2022, 170, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotsos, C.A.; Tzanis, C.G.; Sarlis, N.V. On the progress of the 2015–2016 El Niño event. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 2007–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotsos, C.A.; Tzanis, C.; Cracknell, A.P. Precursory Signals of the Major El Niño Southern Oscillation Events. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016, 124, 903–912. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00704-015-1464-4 (accessed on 10 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Diagnostic Discussion, Issued by Climate Prediction Center. 2023. Available online: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_advisory/ensodisc.shtml (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Varotsos, P.A. Is time continuous? arXiv 2006, arXiv:cond-mat/0605456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlis, N.V.; Skordas, E.S.; Varotsos, P.A. Similarity of fluctuations in systems exhibiting Self-Organized Criticality. EPL 2011, 96, 28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundle, J.B.; Turcotte, D.L.; Donnellan, A.; Grant Ludwig, L.; Luginbuhl, M.; Gong, G. Nowcasting earthquakes. Earth Space Sci. 2016, 3, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotsos, P.A.; Sarlis, N.V.; Skordas, E.S. Natural Time Analysis: The New View of Time, Part II. Advances in Disaster Prediction Using Complex Systems; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrekar, J.N. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve in Diagnostic Test Assessment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 1315–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalkhen, A.G.; McCluskey, A. Clinical tests: Sensitivity and specificity. CEACCP 2008, 8, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlis, N.V.; Christopoulos, S.-R.G. Visualization of the significance of Receiver Operating Characteristics based on confidence ellipses. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 1172–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guignard, F.; Mauree, D.; Lovallo, M.; Kanevski, M.; Telesca, L. Fisher–Shannon Complexity Analysis of High-Frequency Urban Wind Speed Time Series. Entropy 2019, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercik, S.; Weron, K.; Siwy, Z. Statistical analysis of ionic current fluctuations in membrane channels. Phys. Rev. E 1999, 60, 7343–7348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotsos, C.A.; Efstathiou, M.N.; Christodoulakis, J. The lesson learned from the unprecedented ozone hole in the Arctic in 2020 A novel nowcasting tool for such extreme event. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2020, 207, 105330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotsos, C.A.; Mazei, Y.; Novenko, E.; Tsyganov, A.N.; Olchev, A.; Pampura, T.; Mazei, N.; Fatynina, Y.; Saldaev, D.; Efstathiou, M.A. New Climate Nowcasting Tool Based on Paleoclimatic Data. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y. The “Natural Time” Method Used for the Potential Assessment for Strong Earthquakes in China Seismic Experimental Site. In Natural Hazards-New Insights; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutenberg, B.; Richter, C.F. Frequency of earthquakes in California. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1944, 34, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, D.L. Fractals and Chaos in Geology and Geophysics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, S.M.; Tebbens, S.F. The Upper-Truncated Power Law Applied to Earthquake Cumulative Frequency-Magnitude Distributions: Evidence for a Time-Independent Scaling Parameter. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2002, 92, 2983–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begun, R.A.; Lempert, R.J. Climate Reference Periods, Global Warming Levels and Common Climate Dimensions. In Point of Departure and Key Concepts; Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegria, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Loschke, S., Okem, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 121–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirani, A.; Fuglestvedt, J.S.; Byers, E.; O’Neill, B.; Riahi, K.; Lee, J.Y.; Marotzke, J.; Rose, S.K.; Schaeffer, R.; Tebaldi, C. Scenarios in IPCC assessments: Lessons from AR6 and opportunities for AR7. Npj Clim. Action 2024, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Kug, J.S.; An, S.I.; Jin, F.F.; McPhaden, M.J.; Shin, J. Emergent climate change patterns originating from deep ocean warming in climate mitigation scenarios. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Abraham, J.; Trenberth, K.E.; Boyer, T.; Mann, M.E.; Zhu, J.; Wang, F.; Yu, F.; Locarnini, R.; Fasullo, J.; et al. New Record Ocean Temperatures and Related Climate Indicators in 2023. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benschop, N.D.; Chironda-Chikanya, G.; Naidoo, S.; Jafta, N.; Ramsay, L.F.; Naidoo, R.N. El Niño, Rainfall and Temperature Patterns Influence Perinatal Mortality in South Africa: Health Services Preparedness and Resilience in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change and Human Health Scenarios: International Case Studies; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, R.R.; Feron, S.; Damiani, A.; Carrasco, J.; Karas, C.; Wang, C.; Kramwinkel, C.T.; Beaulieu, A. Extreme fire weather in Chile driven by climate change and El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira-Júnior, J.F.; Mendes, D.; Szabo, S.; Singh, S.K.; Jamjareegulgarn, P.; Cardoso, K.R.A.; Bertalan, L.; da Silva, M.V.; da Rosa Ferraz Jardim, A.M.; da Silva, J.L.B.; et al. Impact of the El Niño on Fire Dynamics on the African Continent. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 8, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, A.; Kumar, D.; Khati, B.S. A review on climate change impacts, models, and its consequences on different sectors: A systematic approach. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2024, 15, 104–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ONI Value x0 | Nowcasted Mean Inter-Event Time t [in Years] | The Lower Limit of the 95% Confidence Interval of t. | The Upper Limit of the 95% Confidence Interval of t. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.74 | 3.0 (2.6) | 2.5 (2.2) | 3.7 (3.2) |

| 1.84 | 3.5 (3.1) | 2.9 (2.6) | 4.3 (3.8) |

| 1.94 | 4.1 (3.6) | 3.4 (3.1) | 5.1 (4.4) |

| 2.04 | 4.8 (4.3) | 4.0 (3.6) | 6.0 (5.2) |

| 2.14 | 9.2 (8.2) | 7.6 (6.9) | 11.4 (10.0) |

| 2.24 | 12.1 (10.8) | 10.1 (9.2) | 15.1 (13.2) |

| 2.57 | 51.4 (45.9) | 42.8 (38.9) | 64.3 (56.0) |

| 2.64 | 102.1 (91.2) | 85.1 (77.3) | 127.6 (111.1) |

| SOI Value x0 | Nowcasted Mean Inter-Event Time t [in Years] | The Lower Limit of the 95% Confidence Interval of t | The Upper Limit of the 95% Confidence Interval of t |

|---|---|---|---|

| −19.0 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| −21.3 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 6.8 |

| −21.7 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 7.2 |

| −26.1 | 12.5 | 10.4 | 15.6 |

| −30.0 | 24.6 | 20.6 | 30.6 |

| −31.4 | 31.4 | 26.2 | 39.1 |

| −35.7 | 66.3 | 55.4 | 82.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varotsos, C.; Sarlis, N.V.; Mazei, Y.; Saldaev, D.; Efstathiou, M. A Composite Tool for Forecasting El Niño: The Case of the 2023–2024 Event. Forecasting 2024, 6, 187-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast6010011

Varotsos C, Sarlis NV, Mazei Y, Saldaev D, Efstathiou M. A Composite Tool for Forecasting El Niño: The Case of the 2023–2024 Event. Forecasting. 2024; 6(1):187-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast6010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarotsos, Costas, Nicholas V. Sarlis, Yuri Mazei, Damir Saldaev, and Maria Efstathiou. 2024. "A Composite Tool for Forecasting El Niño: The Case of the 2023–2024 Event" Forecasting 6, no. 1: 187-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast6010011

APA StyleVarotsos, C., Sarlis, N. V., Mazei, Y., Saldaev, D., & Efstathiou, M. (2024). A Composite Tool for Forecasting El Niño: The Case of the 2023–2024 Event. Forecasting, 6(1), 187-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast6010011