Analysis of Touristification Processes in Historic Town Centers: The City of Seville

Abstract

:1. Introduction

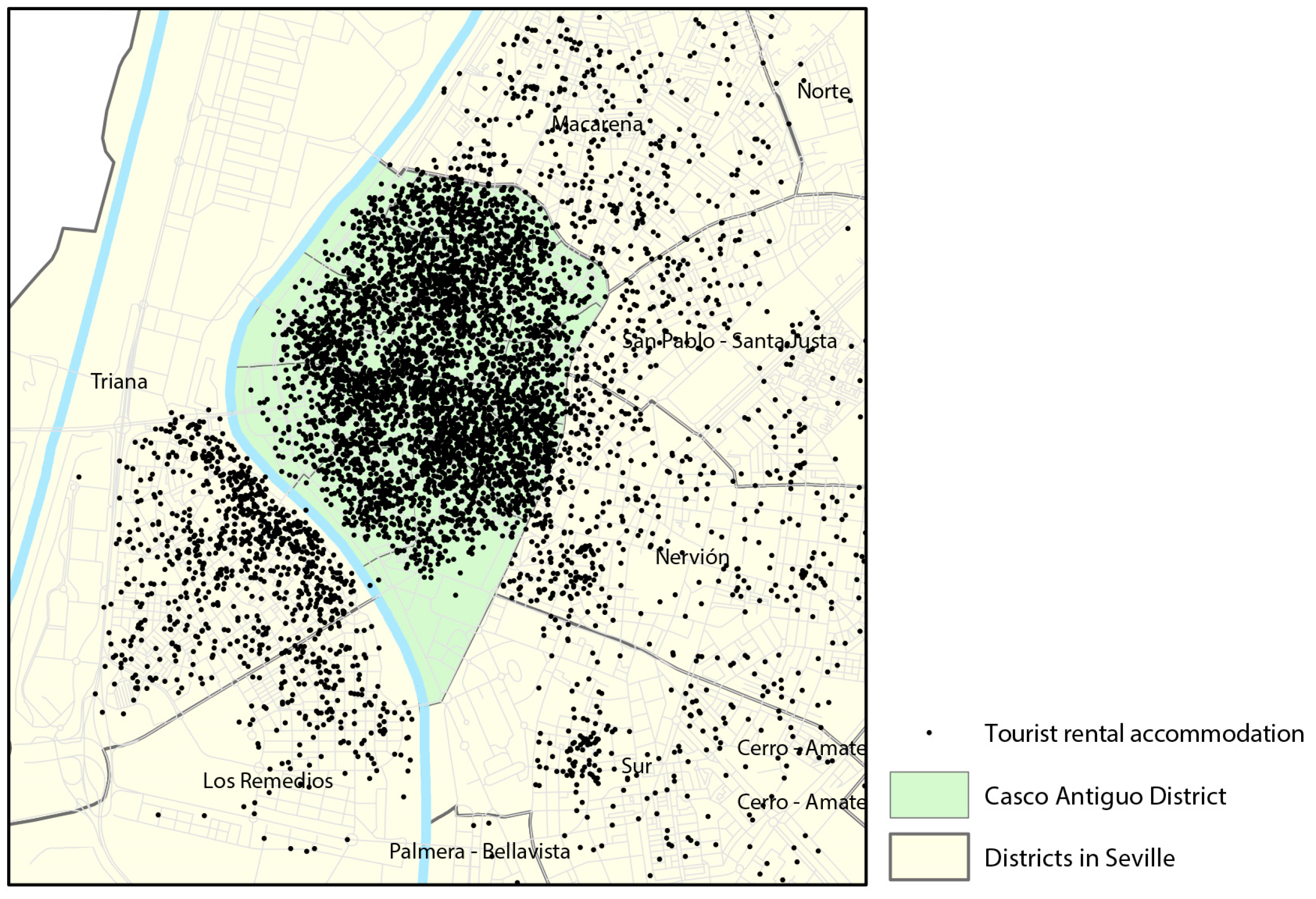

2. Methodology

3. Results

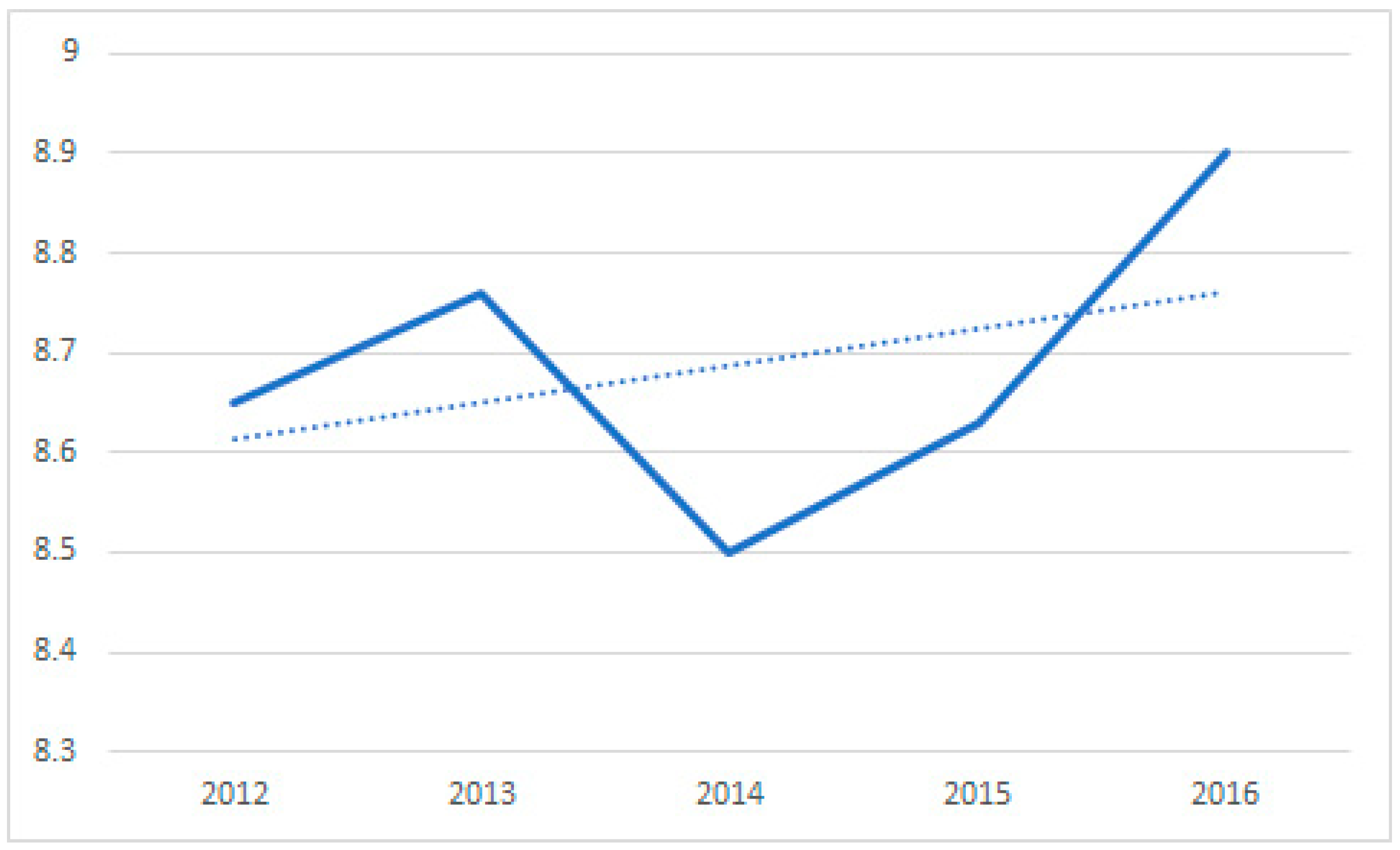

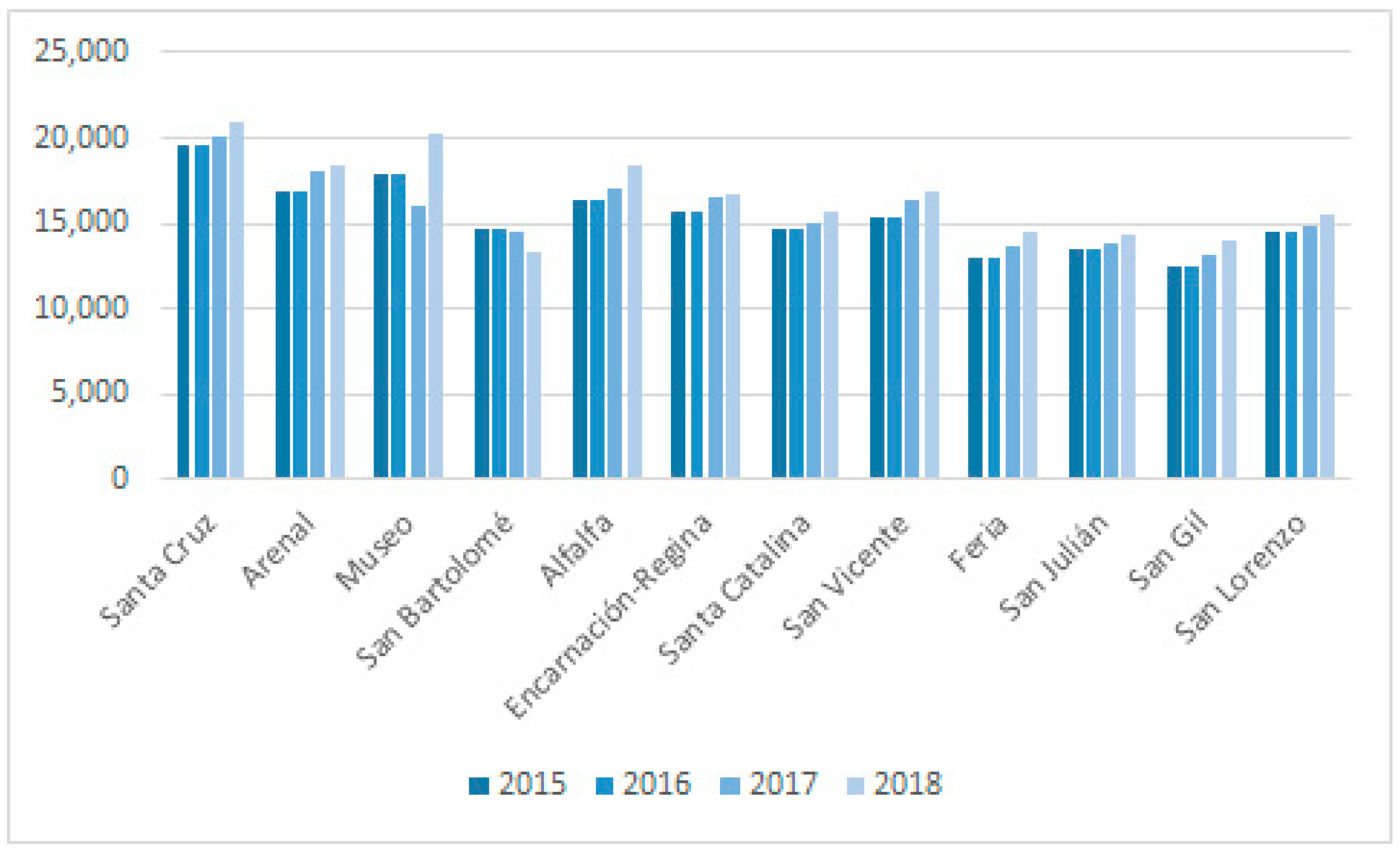

3.1. Demographic Analysis

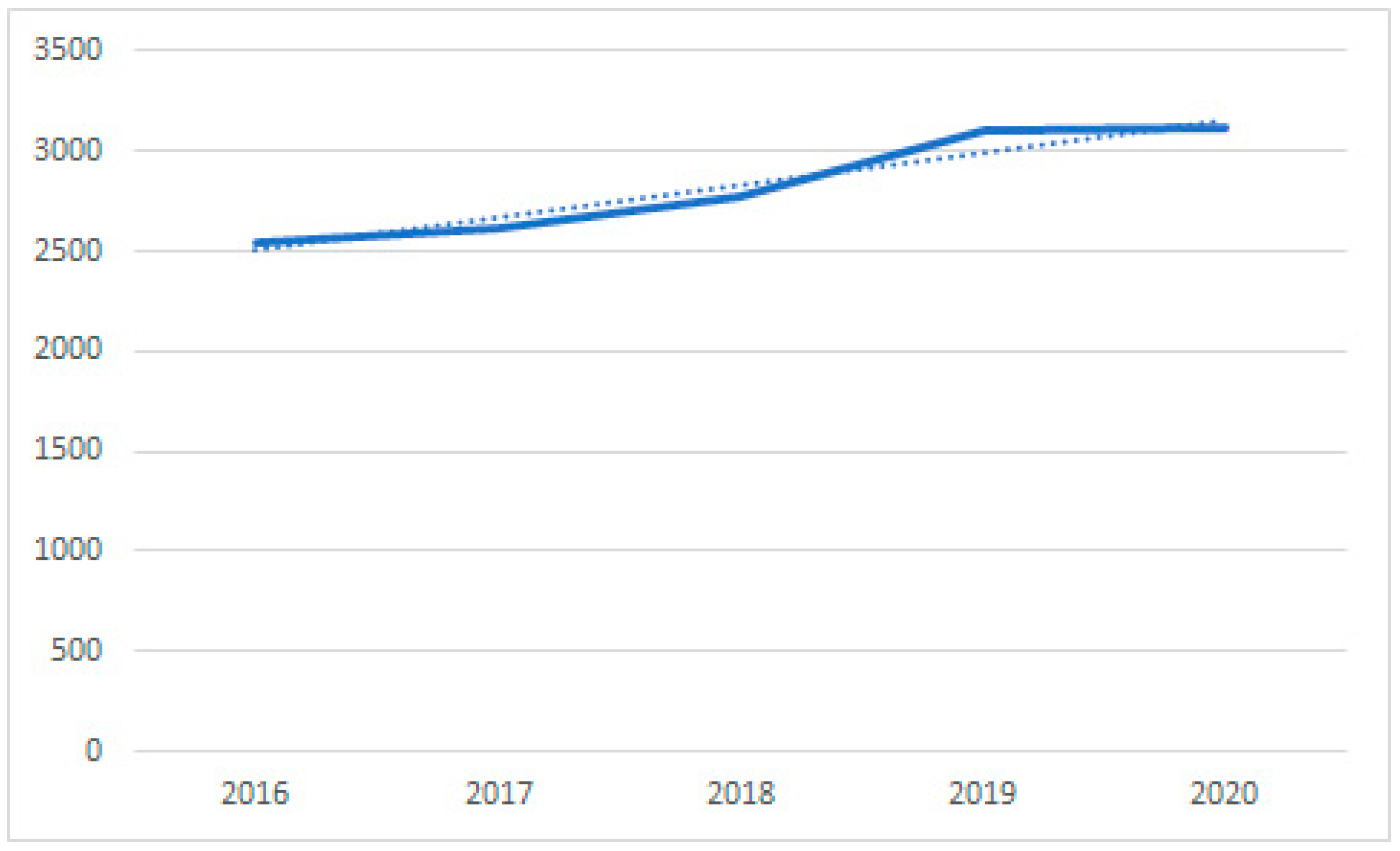

3.2. Economic Analysis

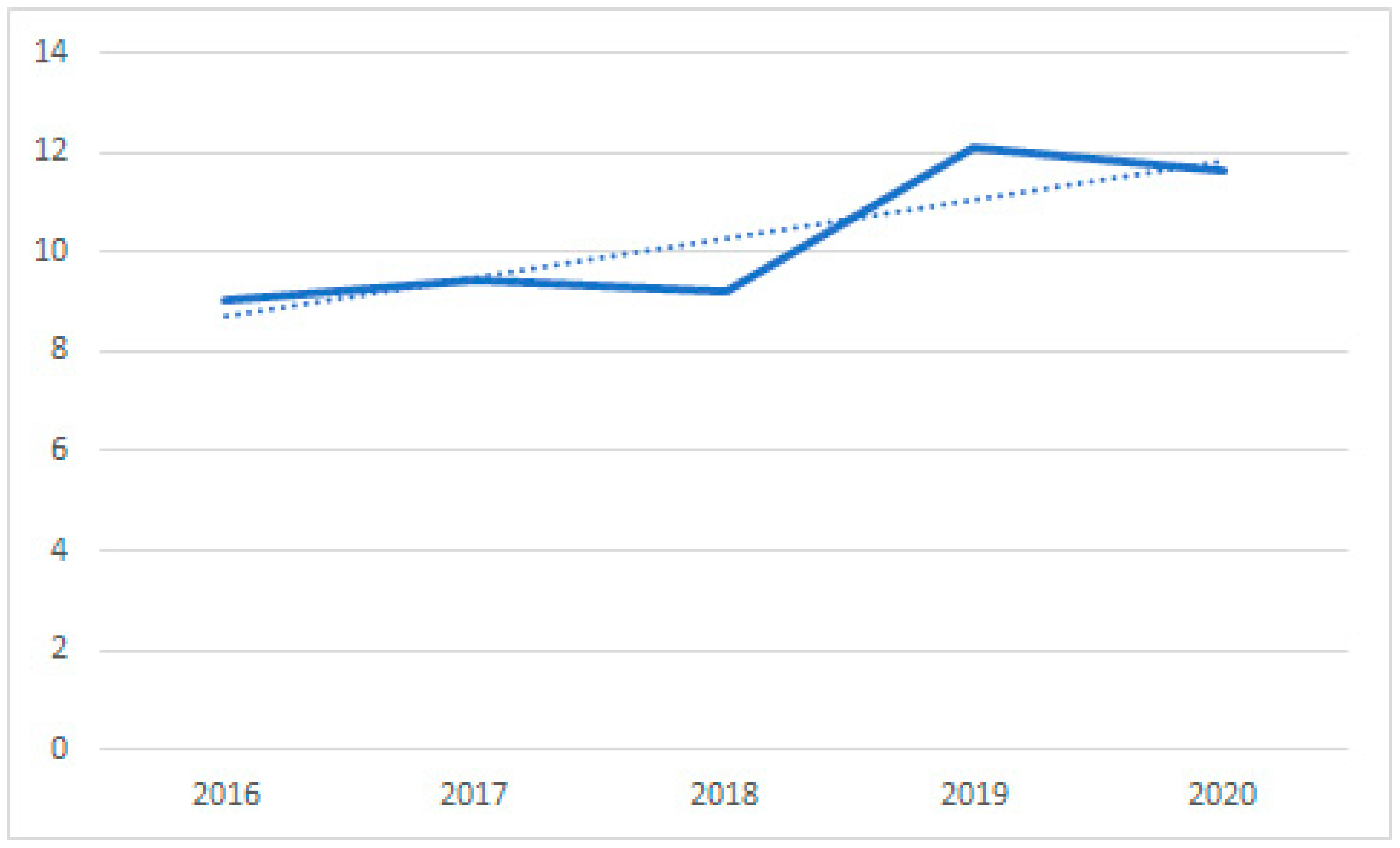

3.3. Socio-Cultural Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Díaz Parra, I. Vender Una Ciudad: Gentrificación y Turistificación en los Centros Históricos; Sostenibilidad n° 10; Editorial Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, P. Research for TRAN Committee–Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses. 2018. Available online: http://bit.ly/2srgoyg (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Rebollo, J.F.V.; Gómez, M.M. Turismo y Desarrollo: Un planteamiento actual. Pap. Tur. 1990, 3, 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Füller, H.; Michel, B. ‘Stop Being a Tourist!’ New Dynamics of Urban Tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrado, J.M.; Duque-Calvache, R.; Zondag, R.N. Towards a dual city? suburbanization and centralization in spain’s largest cities. Rev. Esp. Investig. Sociol. 2021, 176, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.F. Tourism Gentrification: The Case of New Orleans’ Vieux Carre (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 145–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas-Carbonell, A.; Anguelovski, I.; Oscilowicz, E.; Pérez-del-Pulgar, C.; Shokry, G. From greening the climate-adaptive city to green climate gentrification? Civic perceptions of short-lived benefits and exclusionary protection in Boston, Philadelphia, Amsterdam and Barcelona. Urban Clim. 2023, 48, 101295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerena-Rongvaux, N. ¿Renovación sin gentrificación? Hacia un abordaje crítico de procesos urbanos excluyentes en América Latina. Casos en Buenos Aires. EURE 2023, 49, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P. Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Overtourism: A Literature Review to Assess Implications and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, C.; Santos, M.C.; Águas, P.; Santos, J.A.C. Sustainability as a key driver to address challenges. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, F.; Zhai, W.; Wang, Z. Visualizing the Landscape of Green Gentrification: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Directions. Land 2023, 12, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Parra, I. Viaje solo de ida. Gentrificación e intervención urbanística en Sevilla. EURE 2015, 122, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez, J.J. Geography of shopping in historic districts: Between gentrification and heritagezation. A study case in Seville. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2019, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. El Derecho a la Ciudad; Ediciones Península: Barcelona, Spain, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. Thinking cities through elsewhere: Comparative tactics for a more global urban studies. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 40, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parralejo, J.J.; Díaz-Parra, I. Gentrification and Touristification in the Central Urban Areas of Seville and Cádiz. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescalvo, M.B.; Báez, J.J. Landscapes of touristification: A methodological approach through the case of Seville. Cuad. Geogr. 2021, 60, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parralejo, J.J.; Díaz-Parra, I.; Pedregal, B. Sociodemographic processes and tourist rentals in historic centers. The cases of Seville and Cadiz. EURE 2022, 48, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mínguez, C.; Piñeira, M.J.; Fernández-Tabales, A. Social vulnerability and touristification of historic centers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuño, A.; Jiménez, J.L. Economía de plataformas y turismo en España a través de Airbnb. Cuad. Econ. ICE 2019, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, D.; Weisler, A. Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy. Environ. Plan. A 2018, 50, 1147–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle Ramos, C.; Jiménez, C.E.; Calmaestra, J.A.N. Urban renewal processes as mitigators of disadvantaged and vulnerable situations: Analysis in Seville city. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.J.P. Evaluación de Los Efectos de la Gentrificación y la Turistificación Sobre Áreas Urbanas Centrales: Los Casos de Sevilla y Cádiz. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Seville, Seville, Spain, 2021. Available online: https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/130653/Parralejo%20S%C3%A1nchez%2C%20Julio_tesis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Available online: https://www.ine.es/index.htm (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- DataHippo. Tourist Dwellings. Available online: https://datahippo.org/es/ (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Orellana-Alvear, B.; Calle-Jiménez, T. Analysis of the Gentrification Phenomenon Using GIS to Support Local Government Decision Making. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuario Estadístico de la Ciudad de Sevilla, Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, 2015–2020. Available online: https://www.sevilla.org/servicios/servicio-de-estadistica/datos-estadisticos/anuarios/anuario-estadistico-de-la-ciudad-de-sevilla-2020 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Indicadores Demográficos de Sevilla, 2017, Servicio de Estadística, Ayuntamiento de Sevilla. Available online: https://www.sevilla.org/servicios/servicio-de-estadistica/datos-estadisticos/indicadores-demograficos/analisis-indicadores-demograficos.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía (DERA). Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/dega/datos-espaciales-de-referencia-de-andalucia-dera (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Núñez-Camarena, G.M.; Clavijo-Núñez, S.; Rey-Pérez, J.; Aladro-Prieto, J.M.; Roa-Fernández, J. Memory and Identity: Citizen Perception in the Processes of Heritage Enhancement and Regeneration in Obsolete Neighborhoods—The Case of Polígono de San Pablo, Seville. Land 2023, 12, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasse, A.; Sarella-Robles, M.; Cáceres-Quiero, G.; Sabatini, F.; Gomez-Maturano, R.; Trebilcock, M.P. Methods for the identification of gentrifying zones. Santiago de Chile and Mexico City. Bitacora Urbano Territ. 2019, 29, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Bridge, G. Agustin Cocola-Grant the Order and Simplicity of Gentrification. A Political Challenge. In Gentrification in a Global Context: The New Urban Colonialism; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herruzo-Domínguez, G.; Aladro-Prieto, J.-M.; Rey-Pérez, J. Analysis of Touristification Processes in Historic Town Centers: The City of Seville. Architecture 2024, 4, 24-34. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture4010003

Herruzo-Domínguez G, Aladro-Prieto J-M, Rey-Pérez J. Analysis of Touristification Processes in Historic Town Centers: The City of Seville. Architecture. 2024; 4(1):24-34. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture4010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerruzo-Domínguez, Germán, José-Manuel Aladro-Prieto, and Julia Rey-Pérez. 2024. "Analysis of Touristification Processes in Historic Town Centers: The City of Seville" Architecture 4, no. 1: 24-34. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture4010003

APA StyleHerruzo-Domínguez, G., Aladro-Prieto, J.-M., & Rey-Pérez, J. (2024). Analysis of Touristification Processes in Historic Town Centers: The City of Seville. Architecture, 4(1), 24-34. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture4010003