Organizational Structure and Artificial Intelligence. Modeling the Intraorganizational Response to the AI Contingency

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Basic Assumptions for the Model’s Development

- RQ1: What are the plausible influences of the development of AI on the single organizational variables of micro and meso levels of analysis?

- RQ2: How do employees vary according to their explicit attitudes towards organizational changes related to the increasing development and adoption of AI by businesses?

- RQ3: What is the best strategy to implement AI-driven changes in the organization given the potential of organizational inertia and resistance resulting from employees’ negative attitudes towards novel intelligent technologies?

2. Best Organizational Fits to the AI Contingency. Evidence from the Literature

2.1. Micro-Organizational Variables. Job Variety and Job Richness

2.2. Horizontal Axis of Meso-Organizational Specialization. Span of Control

2.3. Vertical Axis of Meso-Organizational Specialization. Decentralization and Chain of Command

2.4. Coordination Mechanisms of Meso-Organizational Specialization. Standardization, Formalization, and Incentives

2.5. Overview of the Formulated Hypotheses

3. Understanding the Attitudes of Jobholders towards Hypothesized Organizational Changes

3.1. Operationalization and Data Gathering

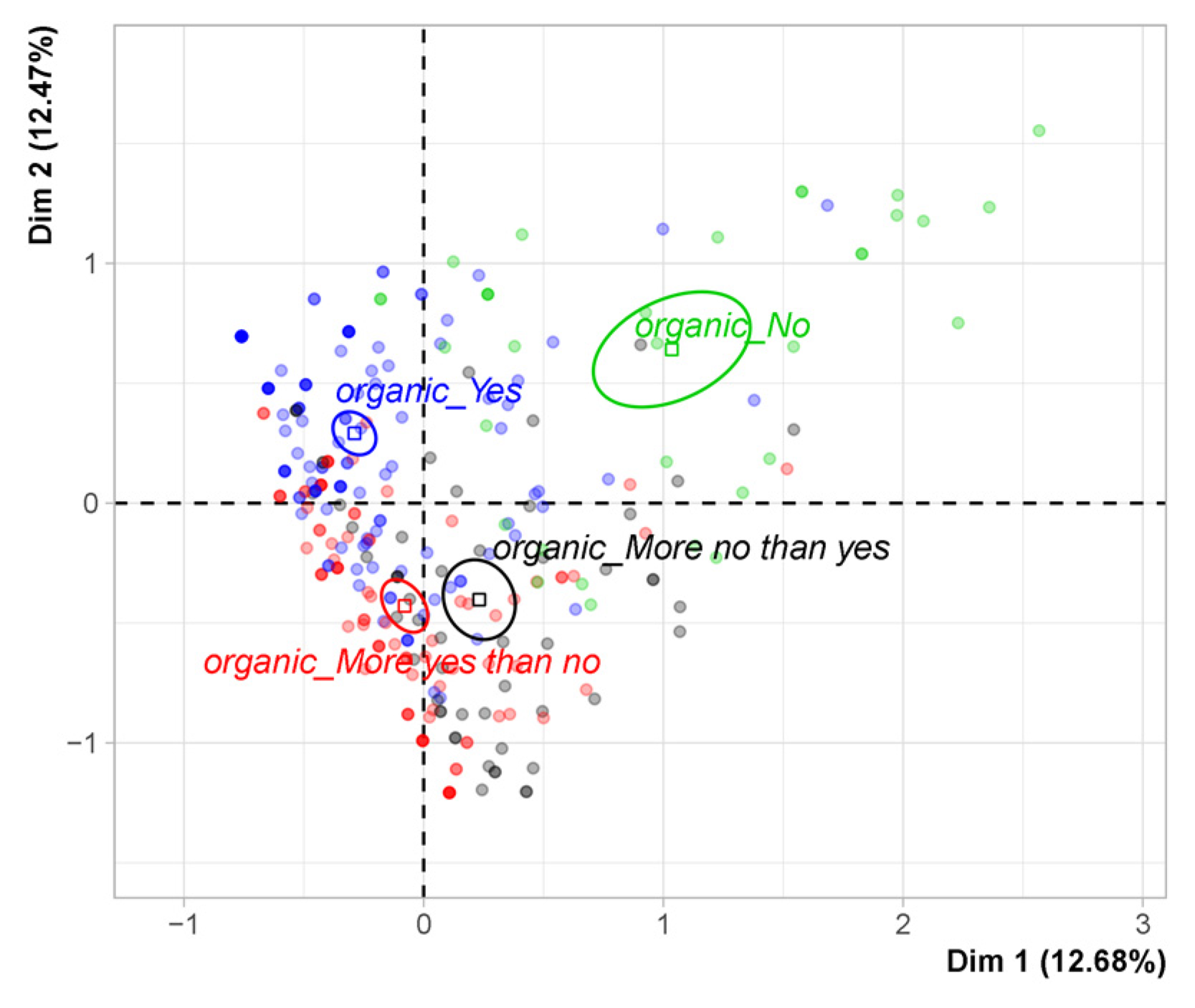

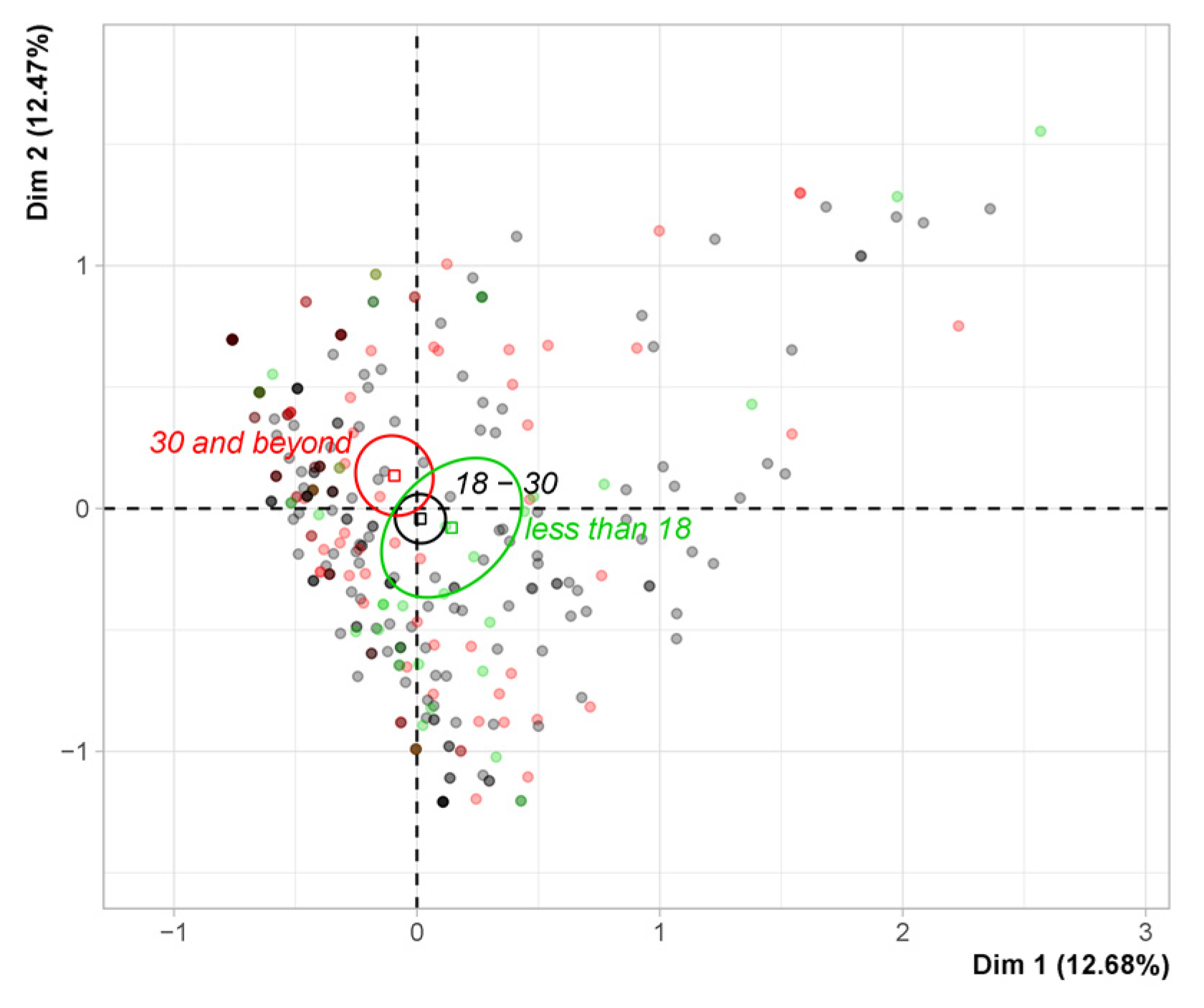

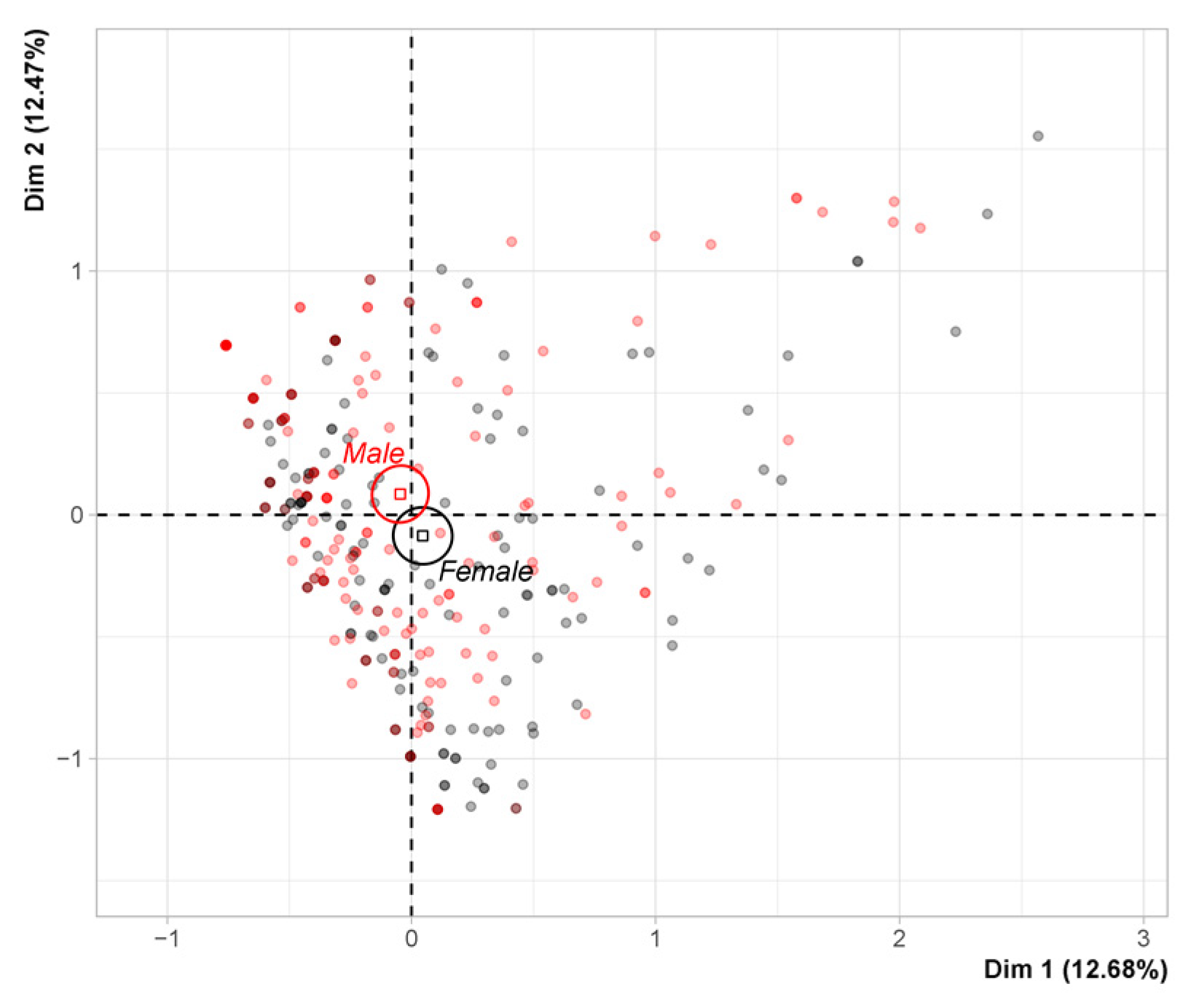

3.2. Exploratory Analysis

4. Formalization of the Model and Discussion

- Individuals within the group hold weaker positive attitudes towards the imminent organizational changes, and therefore their attitudes may easily become negative in the future.

- Gender aside, other relevant demographic characteristics of the group (age and academic status) fit the description of cultural intermediaries given by Featherstone [81]. Therefore, individuals belonging to the group are more likely to change the attitudes of others, and they are the most influential trendsetters and early adopters.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Theoretical Implications

5.4. Research Limitations and Further Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Kranzberg, M. The Information Age: Evolution or Revolution? In Information Technologies and Social Transformation; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Makridakis, S. The Forthcoming Artificial Intelligence (AI) Revolution: Its Impact on Society and Firms. Futures 2017, 90, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschen, U.; Pitt, C.; Kietzmann, J. Artificial Intelligence: Building Blocks and an Innovation Typology. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishya, R.; Javaid, M.; Khan, I.H.; Haleem, A. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Applications for COVID-19 Pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, M.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Gardner, L.M. A Dynamic Neural Network Model for Predicting Risk of Zika in Real Time. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bashirpour Bonab, A.; Rudko, I.; Bellini, F. A Review and a Proposal about Socio-Economic Impacts of Artificial Intelligence. In Business Revolution in a Digital Era; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Dima, A.M., D’Ascenzo, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 251–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lula, P.; Dospinescu, O.; Homocianu, D.; Sireteanu, N.-A. An Advanced Analysis of Cloud Computing Concepts Based on the Computer Science Ontology. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 66, 2425–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmert-Streib, F.; Yli-Harja, O.; Dehmer, M. A Clarification of Misconceptions, Myths and Desired Status of Artificial Intelligence. arXiv 2020, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirican, C. The Impacts of Robotics, Artificial Intelligence on Business and Economics. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. The Business of Artificial Intelligence. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Shi, Q.; Lee, C. From Flexible Electronics Technology in the Era of IoT and Artificial Intelligence toward Future Implanted Body Sensor Networks. APL Mater. 2019, 7, 031302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donaldson, L. The Contingency Theory of Organizations; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-7619-1574-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg, A.; Venkatraman, N. Contingency Perspectives of Organizational Strategy: A Critical Review of the Empirical Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isotta, F. La Progettazione Organizzativa; CEDAM: Padova, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-88-13-31748-5. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, A.; Jack, S.; Farmer, J.; Steinerowska-Streb, I. Are They Really a New Species? Exploring the Emergence of Social Entrepreneurs through Giddens’ Structuration Theory. Bus. Soc. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty, P.; Purdy, M. Why Artificial Intelligence Is a Future of Growth? Accenture 2017. Available online: https://dl.icdst.org/pdfs/files2/2aea5d87070f0116f8aaa9f545530e47.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2017).

- Hendler, J. Intelligent Agents: Where AI Meets Information Technology. IEEE Expert 1996, 11, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P. Robots and Organization Studies: Why Robots Might Not Want to Steal Your Job. Organ. Stud. 2019, 40, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, K.; Salvatier, J.; Dafoe, A.; Zhang, B.; Evans, O. Viewpoint: When Will AI Exceed Human Performance? Evidence from AI Experts. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 62, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Togay, G.; Côté, A.-M. Artificial Intelligence: A Destructive and yet Creative Force in the Skilled Labour Market. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2021, 24, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Jain, R.; Brennan-Tonetta, P.; Swartz, E.; Silver, D.; Paolini, J.; Mamonov, S.; Hill, C. Impact of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence on Industry: Developing a Workforce Roadmap for a Data Driven Economy. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2021, 22, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, L.; Azar, J.; Giné, M.; Samila, S.; Taska, B. The Demand for AI Skills in the Labor Market. Labour Econ. 2021, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volini, E.; Schwartz, J.; Denny, B.; Mallon, D.; von Durme, Y.; Hauptmann, M.; Yan, R.; Poynton, S. 2020 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends; Deloitte Report; Deloitte: Shanghai, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Volini, E.; Occean, P.; Stephan, M.; Walsh, B. 2017 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends; Deloitte Report; Deloitte: Shanghai, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, S.E. A Strategic Framework for Task Automation in Professional Services. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Mitchell, T.; Rock, D. What Can Machines Learn, and What Does It Mean for Occupations and the Economy? AEA Pap. Proc. 2018, 108, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKendrick, J. Artificial Intelligence Will Replace Tasks, Not Jobs. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/joemckendrick/2018/08/14/artificial-intelligence-will-replace-tasks-not-jobs/ (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Dospinescu, O.; Ilinca, L. The Recognition of Fingerprints on Mobile Applications—An Android Case Study. J. East. Eur. Res. Bus. Econ. 2016, 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Arun, C.J.; Varma, A. Rebooting Employees: Upskilling for Artificial Intelligence in Multinational Corporations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisskirchen, G.; Biacabe, B.T.; Bormann, U.; Muntz, A.; Niehaus, G.; Soler, G.J.; von Brauchitsch, B. Artificial Intelligence and Robotics and Their Impact on the Workplace; IBA Global Employment Institute: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarz, A.; Malinowska, D. From Psychological Theoretical Assumptions to New Research Perspectives in Sustainability and Sustainable Development: Motivation in the Workplace. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malik, N.; Tripathi, S.N.; Kar, A.K.; Gupta, S. Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employees Working in Industry 4.0 Led Organizations. Int. J. Manpow. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, S. A Critical Review of Impact of Job Enrichment and Employee Performance, Motivation and Productivity. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Dev. 2020, 3, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, J.R. Designing Organizations: Strategy, Structure, and Process. at the Business Unit and Enterprise Levels; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-40995-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, S.; Martin, R.; Harris, M. Decentralization, Integration and the Post-Bureaucratic Organization: The Case of R&d. J. Manag. Stud. 2000, 37, 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čudanov, M.; Jaško, O.; Jevtić, M. Influence of Information and Communication Technologies on Decentralization of Organizational Structure. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2009, 6, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, P.S.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Han, Y. Team Empowerment and the Organizational Context: Decentralization and the Contrasting Effects of Formalization. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 475–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.I. Automation as Part of the Solution. J. Manag. Inq. 2019, 28, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.W. Is “Empowerment” Just a Fad? Control, Decision-Making, and Information Technology. BT Technol. J. 1999, 17, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Vyas, S. Decentralized Autonomous Organizations = Blockchain + AI + IoT. In How to Compete in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: Implementing a Collaborative Human-Machine Strategy for Your Business; Mohanty, S., Vyas, S., Eds.; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 189–206. ISBN 978-1-4842-3808-0. [Google Scholar]

- DuBrin, A.J. Fundamentals of Organizational Behavior: An Applied Perspective; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4831-4817-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, R.G.; Wulf, J. The Flattening Firm: Evidence from Panel Data on the Changing Nature of Corporate Hierarchies. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2006, 88, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawler, E.E. Substitutes for Hierarchy. Organ. Dyn. 1988, 17, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.A.; Hammond, T.; Harrington, J. Disruptive Technology: Economic Consequences of Artificial Intelligence and the Robotics Revolution. J. Strat. Innov. Sustain. 2017, 12, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.C.; Bostrom, N. Future Progress in Artificial Intelligence: A Survey of Expert Opinion. In Fundamental Issues of Artificial Intelligence; Müller, V.C., Ed.; Synthese Library; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 555–572. ISBN 978-3-319-26485-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fountaine, T.; McCarthy, B.; Saleh, T. Building the AI-Powered Organization. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 97, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, M.A. Strategic Management of Technological Innovation, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-93-5316-846-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kanten, P.; Kanten, S.; Gurlek, M. The Effects of Organizational Structures and Learning Organization on Job Embeddedness and Individual Adaptive Performance. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powell, T.C. Organizational Alignment as Competitive Advantage. Strat. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z.; Haugaard, M. Liquid Modernity and Power: A Dialogue with Zygmunt Bauman. J. Power 2008, 1, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillerman, J. The Sociology of Consumption: A Global Approach; John Wiley & Son: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-7456-9691-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-7456-5701-1. [Google Scholar]

- Leiss, W.; Beck, U.; Ritter, M.; Lash, S.; Wynne, B. Risk Society, Towards a New Modernity. Can. J. Sociol. Cah. Can. Sociol. 1995, 19, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.; Stalker, G.M. Mechanistic and Organic Systems of Management. In Sociology of Organizations: Structures and Relationships; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4129-9196-4. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T.; Stalker, G.M. The Management of Innovation; Tavistock Publishing: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Puaschunder, J.M. Artificial Intelligence Market Disruption. In Proceedings of the International RAIS Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities, Rockville, MD, USA, 10–11 June 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner, S.E.; Sprinkle, G.B. The Effects of Monetary Incentives on Effort and Task Performance: Theories, Evidence, and a Framework for Research. Acc. Organ. Soc. 2002, 27, 303–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponta, L.; Delfino, F.; Cainarca, G.C. The Role of Monetary Incentives: Bonus and/or Stimulus. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdullah, A.A.; Wan, H.L. Relationships of Non-Monetary Incentives, Job Satisfaction and Employee Job Performance. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2013, 2, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, V.; Adams, O. Pay and Non-pay Incentives, Performance and Motivation. In Studies in HSO&P; ITGPress: Antwerp, Belgium, 2003; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, L.A.; Freeman, R.B. The Incentive for Working Hard: Explaining Hours Worked Differences in the US and Germany. Labour Econ. 2001, 8, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sparks, K.; Cooper, C.; Fried, Y.; Shirom, A. The Effects of Hours of Work on Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurgeon, A.; Harrington, J.M.; Cooper, C.L. Health and Safety Problems Associated with Long Working Hours: A Review of the Current Position. Occup. Environ. Med. 1997, 54, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.; Holton, R.J. Technology, Innovation, Employment and Power: Does Robotics and Artificial Intelligence Really Mean Social Transformation? J. Sociol. 2018, 54, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, I.M.; Henderson, R.; Stern, S. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Innovation; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Helbing, D.; Frey, B.S.; Gigerenzer, G.; Hafen, E.; Hagner, M.; Hofstetter, Y.; van den Hoven, J.; Zicari, R.V.; Zwitter, A. Will Democracy Survive Big Data and Artificial Intelligence? In Towards Digital Enlightenment: Essays on the Dark and Light Sides of the Digital Revolution; Helbing, D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 73–98. ISBN 978-3-319-90869-4. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, D.L. Bringing Bourdieu’s Master Concepts into Organizational Analysis. Theory Soc. 2008, 37, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977; ISBN 978-0-521-29164-4. [Google Scholar]

- Power, E.M. An Introduction to Pierre Bourdieu’s Key Theoretical Concepts. J. Study Food Soc. 1999, 3, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.K.; Mahmud, Z.; Noranee, S.; Noordin, F. Measuring Employee Happiness: Analyzing the Dimensionality of Employee Engagement. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Kansei Engineering and Emotion Research 2018; Lokman, A.M., Yamanaka, T., Lévy, P., Chen, K., Koyama, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 863–869. [Google Scholar]

- Saari, L.M.; Judge, T.A. Employee Attitudes and Job Satisfaction. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jost, J.T. The IAT Is Dead, Long Live the IAT: Context-Sensitive Measures of Implicit Attitudes Are Indispensable to Social and Political Psychology. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 28, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M. Predictive Models of Implicit and Explicit Attitudes. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 44, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and Managing the Threat of Common Method Bias: Detection, Prevention and Control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.W. Convenience Sampling, Random Sampling, and Snowball Sampling: How Does Sampling Affect the Validity of Research? J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2015, 109, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Tuten, T.L. Prepaid and Promised Incentives in Web Surveys: An Experiment. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2003, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutskens, E.; de Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M.; Oosterveld, P. Response Rate and Response Quality of Internet-Based Surveys: An Experimental Study. Mark. Lett. 2004, 15, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cobb-Clark, D.A.; Schurer, S. The Stability of Big-Five Personality Traits. Econ. Lett. 2012, 115, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reifman, A.; Arnett, J.J.; Colwell, M.J. Emerging Adulthood: Theory, Assessment and Application. J. Youth Dev. 2007, 2, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Featherstone, M. Lifestyle and Consumer Culture. Theory Cult. Soc. 1987, 4, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, J.S.; Matthews, J. Cultural Intermediaries and the Media. Sociol. Compass 2010, 4, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brougham, D.; Haar, J. Smart Technology, Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, and Algorithms (STARA): Employees’ Perceptions of Our Future Workplace. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minsky, M. The Emotion Machine: Commonsense Thinking, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of the Human Mind; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7432-7664-1. [Google Scholar]

| Intraorganizational Level | Organizational Variable | The Best Fit to AI Contingency (in Terms of the Degree Assumed by an Organizational Variable) | Main Reason | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro (horizontal division of labor) | Variety/scope of job | Low | Initially, AI will not eliminate jobs but remove tasks from jobs | [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] |

| Micro (vertical division of labor) | Richness/autonomy of job | High | Increased job autonomy is the most efficient way to compensate for the reduction in job variety | [20,29,30,31,32,33] |

| Meso (horizontal axis of specialization) | Span of control (size of organizational units) | The effect of AI is unclear | The optimal size of organizational units is the result of the interplay of multiple different factors | [34] |

| Meso (vertical axis of specialization) | Degree of centralization | Low | Decentralization is the major organizational trend significantly influenced by the development of IT | [35,36,37,38,39,40] |

| Meso (vertical axis of specialization) | Number of hierarchical levels (length of the chain of command) | Low | Given its intrinsic properties, AI may be considered the perfect substitute for the hierarchy | [14,41,42,43,44,45,46] |

| Meso (coordination mechanism) | Standardization | Low | As a set of disruptive technologies, AI is contributing to the uncertainty of the economy; therefore, organic structures will be more required | [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] |

| Meso (coordination mechanism) | Formalization | Low | As a set of disruptive technologies, AI is contributing to the uncertainty of the economy; therefore, organic structures will be more required | [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] |

| Meso (coordination mechanism) | Incentives | High | Incentives mainly concern the reduction of the average number of working hours per week (assuming the same wage). AI may significantly contribute to the trend given the high degree of sustainability between simple human tasks and the intelligent technology | [30,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] |

| Questions | Yes | More Yes than No | More No than Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In your future or the current job, would you like to perform less of the mundane activities (like replying to emails or filling in forms)? | 32% | 30.8% | 22.8% | 14.5% |

| Would you like your future or the current employer to provide you with more autonomy, control, and responsibility for the tasks you are performing? | 51.7% | 36.6% | 5.5% | 6.2% |

| Currently or in the future, would you prefer to work in larger work teams? | 27.1% | 18.5% | 35.4% | 19.1% |

| Would you like to work in an organization where your work team is independent of the upper management and is directly responsible for its own decisions and actions? | 49.5% | 34.2% | 10.5% | 5.8% |

| Would you like to work in an organization with fewer bureaucratic levels between you and your manager? | 56.3% | 28.3% | 7.1% | 8.3% |

| Would you like to work in an organization with less formal procedures, codes of behavior, practices, and rules? | 43.4% | 28.9% | 17.2% | 10.5% |

| Given the same wage, would you like to work fewer hours on average? | 52.6% | 26.2% | 12.6% | 8.6% |

| Categories | Dim. 1 | Ctr.% | Cos2 | v. Test | Dim. 2 | Ctr.% | Cos2 | v. Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scope_More no than yes | 0.254 | 0.642 | 0.019 | 2.480 | * | −0.243 | 0.600 | 0.017 | −2.377 | * |

| scope_More yes than no | 0.148 | 0.297 | 0.010 | 1.781 | −0.603 | 4.982 | 0.162 | −7.236 | * | |

| scope_No | 0.917 | 5.332 | 0.142 | 6.789 | * | 0.569 | 2.082 | 0.055 | 4.208 | * |

| scope_Yes | −0.738 | 7.633 | 0.256 | −9.110 | * | 0.496 | 3.504 | 0.116 | 6.123 | * |

| richness_More no than yes | 1.198 | 3.483 | 0.084 | 5.222 | * | 0.272 | 0.183 | 0.004 | 1.186 | |

| richness_More yes than no | 0.249 | 0.996 | 0.036 | 3.409 | * | −0.788 | 10.117 | 0.358 | −10.77 | * |

| richness_No | 0.730 | 1.439 | 0.035 | 3.367 | * | 0.983 | 2.651 | 0.063 | 4.533 | * |

| richness_Yes | −0.392 | 3.477 | 0.164 | −7.296 | * | 0.412 | 3.902 | 0.181 | 7.665 | * |

| decentralization_More no than yes | 0.604 | 1.672 | 0.043 | 3.716 | * | −0.748 | 2.606 | 0.065 | −4.602 | * |

| decentralization_More yes than no | −0.080 | 0.095 | 0.003 | −1.032 | −0.720 | 7.891 | 0.269 | −9.337 | * | |

| decentralization_No | 2.207 | 12.482 | 0.303 | 9.901 | * | 0.909 | 2.152 | 0.051 | 4.078 | * |

| decentralization_Yes | −0.333 | 2.410 | 0.109 | −5.942 | * | 0.547 | 6.607 | 0.294 | 9.759 | * |

| numb_of_levels_More no than yes | 0.829 | 2.131 | 0.052 | 4.118 | * | −0.580 | 1.061 | 0.026 | −2.883 | * |

| numb_of_levels_More yes than no | 0.169 | 0.352 | 0.011 | 1.906 | −1.013 | 12.945 | 0.405 | −11.46 | * | |

| numb_of_levels_No | 2.157 | 16.937 | 0.422 | 11.687 | * | 1.016 | 3.819 | 0.094 | 5.504 | * |

| numb_of_levels_Yes | −0.507 | 6.346 | 0.331 | −10.36 | * | 0.432 | 4.690 | 0.241 | 8.837 | * |

| organic_More no than yes | 0.376 | 1.066 | 0.029 | 3.087 | * | −0.658 | 3.324 | 0.090 | −5.405 | * |

| organic_More yes than no | −0.129 | 0.209 | 0.007 | −1.476 | −0.701 | 6.328 | 0.200 | −8.048 | * | |

| organic_No | 1.678 | 12.910 | 0.329 | 10.325 | * | 1.048 | 5.114 | 0.128 | 6.445 | * |

| organic_Yes | −0.468 | 4.168 | 0.168 | −7.378 | * | 0.476 | 4.379 | 0.174 | 7.501 | * |

| incentives_More no than yes | 0.239 | 0.316 | 0.008 | 1.635 | −0.333 | 0.624 | 0.016 | −2.279 | * | |

| incentives_More yes than no | 0.039 | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.421 | −0.607 | 4.293 | 0.131 | −6.503 | * | |

| incentives_No | 1.811 | 12.376 | 0.309 | 10.007 | * | 1.176 | 5.308 | 0.130 | 6.500 | * |

| incentives_Yes | −0.373 | 3.214 | 0.155 | −7.082 | * | 0.189 | 0.838 | 0.040 | 3.586 | * |

| Organizational Variable | The Best Fit to AI Contingency (in Terms of the Degree of org. Variable) | Survey Results | Level of Concordance between Overall Explicit Attitudes and the Hypothesized Best Fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variety/scope of job | Low (less of the mundane tasks) | In favor: 32%. Slightly in favor: 30.8%. Slightly in disfavor: 22.8%. In disfavor: 14.5% | Moderate >60% |

| Richness/autonomy of job | High | In favor: 51.7%. Slightly in favor: 36.6%. Slightly in disfavor: 5.5%. In disfavor: 6.2% | Strong >80% |

| Span of control (size of organizational units) | The effect of AI is unclear | In favor of larger teams: 27.1%. Slightly in favor of larger teams: 18.5%. In favor of smaller teams: 19.1%. Slightly in favor of smaller teams: 35.4% | Overall slight preference towards smaller work teams >50% |

| Degree of centralization | Low | In favor: 49.5%. Slightly in favor: 34.2%. Slightly in disfavor: 10.5%. In disfavor: 5.8% | Strong >80% |

| Number of hierarchical levels (length of the chain of command) | Low | In favor: 56.3%. Slightly in favor: 28.3%. Slightly in disfavor: 7.1%. In disfavor: 8.3% | Strong >80% |

| Standardization and formalization | Low (organic structure) | In favor: 43.4%. Slightly in favor: 28.9%. Slightly in disfavor: 17.2%. In disfavor: 10.5% | Moderately strong >70% |

| Incentives | High (fewer working hours on average given the same wage) | In favor: 52.6%. Slightly in favor: 26.2%. Slightly in disfavor: 12.6%. In disfavor: 8.6% | Strong >80% |

| Positive Attitudes | Negative Attitudes | |

|---|---|---|

| Strong attitudes | II Optimists The most stable cohort posing no threat in terms of organizational resistance to changes. MCA maps them as men mostly over 30 years old who have finished their education. Given the strength of their attitudes, no managerial efforts are recommended. | I Skeptics The most problematic group of individuals posing a significant resistance to the upcoming organizational changes. They are, however, significantly outnumbered by individuals belonging to other groups. Managerial efforts to convince them of the positive aspects of changes may be too expensive and ineffective; therefore, no action in their regard is recommended. |

| Weak attitudes | III Doubtful optimists The positive attitudes of this group’s members are weak; managers should implement proactive strategies to make those attitudes more stable. MCA maps the individuals belonging to the group as primarily female, under 30 years old, and still studying. The latter two characteristics fit the profile of cultural intermediaries. This subgroup is highly capable of influencing the attitudes of their own and other groups’ members. | IV Doubtful skeptics Although their attitudes are negative, those individuals remain quite unsure about them. No particular action is recommended, as addressing cultural intermediaries (in group III) more effectively may be the best strategy to convince doubtful skeptics about the positive aspects of organizational changes indirectly. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rudko, I.; Bashirpour Bonab, A.; Bellini, F. Organizational Structure and Artificial Intelligence. Modeling the Intraorganizational Response to the AI Contingency. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2341-2364. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16060129

Rudko I, Bashirpour Bonab A, Bellini F. Organizational Structure and Artificial Intelligence. Modeling the Intraorganizational Response to the AI Contingency. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2021; 16(6):2341-2364. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16060129

Chicago/Turabian StyleRudko, Ihor, Aysan Bashirpour Bonab, and Francesco Bellini. 2021. "Organizational Structure and Artificial Intelligence. Modeling the Intraorganizational Response to the AI Contingency" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16, no. 6: 2341-2364. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16060129

APA StyleRudko, I., Bashirpour Bonab, A., & Bellini, F. (2021). Organizational Structure and Artificial Intelligence. Modeling the Intraorganizational Response to the AI Contingency. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(6), 2341-2364. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16060129