Abstract

IoT (Internet of Things)-enabled products are increasingly used by consumers and continuously propagate in daily life. Billions of networked objects not only increase the complexity of development but also raise user interaction and adaptation to individual needs. The more non-expert users are involved in decision making, interaction, and adaptation processes, the more user-centric IoT design is crucial, particularly when the number of elderly users is steadily increasing. In this paper, we study the capabilities of adopting IoT products through user-informed adaptation in a major IoT application domain, home healthcare. We review evidence from established practice in the field on how users can be supported when aiming to adapt medical IoT (M-IoT) home applications to their needs. We examine the empirically grounded use of IoT sensors and actuators, as well as the adaptation process users adopt when using an IoT application in a personalized environment. Our analysis (technological evidence) reveals various IoT devices that have already been applied in M-IoT adaptation settings to effectively support users. Our analysis reveals that only few empirically sound findings exist on how users actually perceive interactive adaptation features and redesign M-IoT applications. Based on the analysis of these empirically grounded findings, we suggest the development of a domain-specific user-centric adaptation feature. Specifically, we exemplify a tangible adaptation device for user-informed M-IoT application in home healthcare. It has been developed prototypically and tested in an environment for personalized home healthcare.

1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) is increasingly propagating in our lives. IoT applications are driven by the vision of digitally enriched or digital everyday objects, termed “things”, being interconnected and capable of transmitting and receiving data through the Internet. Users and other “things” perceive and sense information as well as interacting via Internet-based services. They perform tasks and rely on both collective intelligence and individual capabilities to sense and act [1]. Besides objects and the environment, people form the main context of operating and evolving IoT applications. Since life expectancy is increasing markedly worldwide, the population—and, thus, user groups—are getting older and older. This development challenges specific application domains, such as medical care, to deliver healthcare services in a demand-driven and user-centred way [2].

As older adults have a desire to stay in their own residence as long as possible, home healthcare is promoted [3]. Medical IoT (M-IoT) technology can help provide relevant services, particularly for personalizing their environment [2,4]. Many systems already offer technological assistance such as monitoring devices, memory aid systems, and emergency response devices. These are mostly designed for a specific disease or scenario, and collect and process the corresponding vital parameters. The sensing capability of M-IoT systems can capture those parameters, thus changing the healthcare sector significantly [5]—they shift healthcare operations to an individual’s home [3]. The connectivity of IoT components enables scalability, resulting in a large number of sensors and communicating systems or actors [6].

Adaptable IoT services have the capability to meet the different expectations of users. Flexible feature arrangements, which can be adapted to the skills and specific requests of users, allow products to be used effectively [2]. However, in mainstream technology, the elderly’s needs and capabilities to adopt complex digital systems for individual use are often neglected [7]. Recent surveys in the QoS of IoT applications mainly focus on technological development topics, such as interoperability, security, and service composition [8,9,10]. Considering user-centred requirements related to reliability and trustworthiness [11], the crucial question is how to design IoT systems that can be adapted to support people in a specific domain given their individual needs and mental models [12]. IoT systems should be easily adaptable by users regardless of their prior IT knowledge (cf. [13]) and in a dynamic way, allowing for just-in-time interventions [14]. Correspondingly, the research question we need to tackle is: How can home healthcare systems be created that can be adapted to support people with different needs?

User-centric adaptation concerns the cognitive and behavioural effort of users appropriating a technology (cf. [15,16]). Hence, the term “adaptation” in this study is understood as a continuous and progressive process involving mutual adjustments, accommodations, and improvisations [16], and requires user involvement in (iterative) design activities [17]. As this process is grounded by the user’s assignment of meaning and significance to technological artefacts, it is a matter of pleasurable products [18] and user experience [19]. We term it user-informed adaptation to better express its meaning.

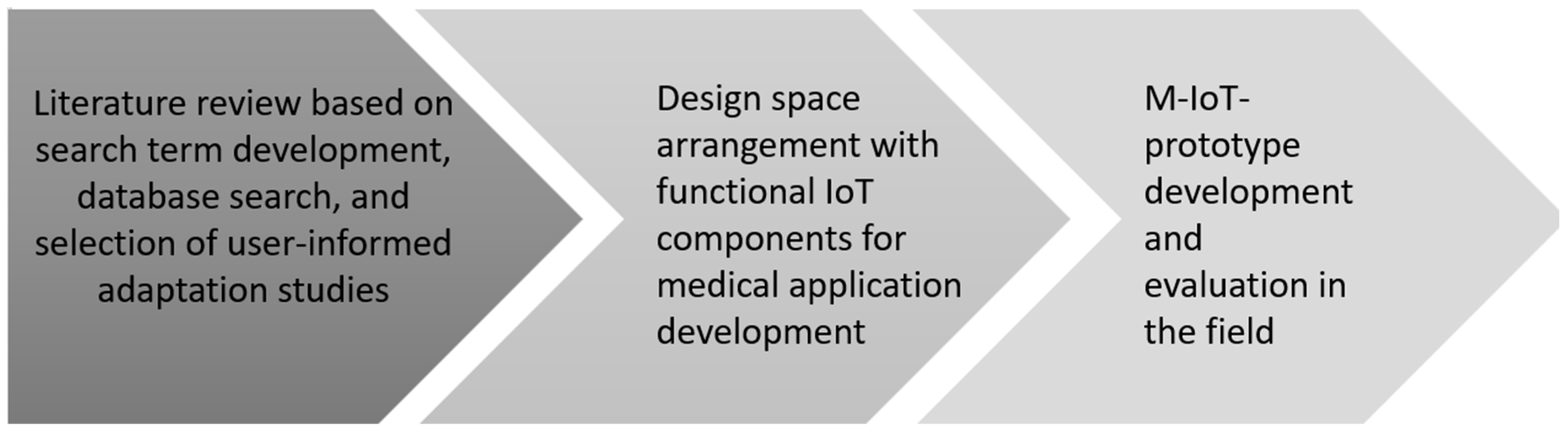

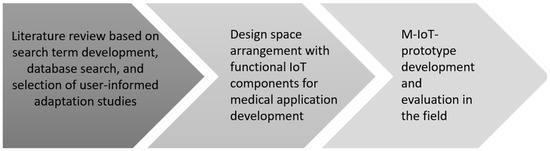

To study adaptable IoT systems based on technological and empirical evidence, we searched for specific user studies. We aimed to reveal the needs of and success factors behind system development, and how needs and success factors can be put into practice. The literature review and analysis are described in Section 2 (see also Figure 1). The findings are structured to design a user-informed adaptation of M-IoT applications. Although many papers referred to various adaptation concepts for technological systems in general, they mainly considered the technological feasibility of an adaptation concept rather than its evaluation from user tests or empirical validation. In addition, since few of the analysed systems had been evaluated with respect to useful and playful user task experience in detail, we had to propose a novel approach following the authors of reference [20], who demonstrated the benefits of tangible user interfaces (TUIs).

Figure 1.

Overall research process.

The developed prototype for the user-informed adaptation of T-Care in Section 3 has been tested in a field study. Questionnaires were used to identify actual use scenarios and check the usability. The involved healthcare users were able to adapt the prototype to the specific scenarios, which indicates that the domain-specific tangible adaptation IoT systems can meet the adaptation requirements in a user-informed way. In Section 4, we conclude by summarizing the findings and sketch future research avenues.

2. Related Work and Research Procedure

Several analyses in the field of Medical Internet of Things (M-IoT) have been performed. They mainly address various healthcare systems and services in terms of accuracy, reliability, performance, and effectiveness. Ref. [4] refers to system architectures, including networked M-IoT devices linked to cloud systems for data collection, storage, and analysis. Capturing, interpreting, and distributing health data using the proper tools brings up security issues (see also reference [9], in particular if users consume services in their residences). In order to improve the users’ quality of life, lower prices, and expand their expertise, smartphones, wearable medical devices, and embedded medical devices are used—they ensure continuous and smooth operation.

Although smart services, e.g., through sensing, are considered a crucial part of Quality of Service (QoS) (cf. [8]), user-informed adaptation is still urged as a research topic on just-in-time interventions [14]. It is envisioned to ‘harness rich data on users’ contexts’, as many adaptation features ‘fall short in leveraging the value of the data while sculpting the interventions’ (ibid.) The study revealed the lack of user-centred design (processes) of adaptation. In particular, informed critical design decisions should be based on user involvement. Users should have the opportunity to control the adaptation process according to their needs.

Ref. [17] studied user needs when users strive for a healthy lifestyle, concerning monitoring and recommending physical activities, and diet habits. The developed coaching system followed clinical and ethical guidelines when referring to individual health status, condition, and preferences. The user involvement targeted the context of use and features for self-managing healthcare procedures. The iterative design process included application prototyping and personalized recommendations including their visualization. Although such approaches enrich the solution space for user-centred QoS-aware services, the composition of services is still one of the big challenges in IoT application development [10]. The mainly used evolution approaches lead to sub-optimal service compositions in reasonable computational time (ibid.). They hinder the user-informed adaptation of healthcare systems, as they also need to connect heterogeneous (wearable) devices [21].

Hence, we need to study user-informed adaptation and configuration from a technological and empirical perspective. The methodology, starting with the literature review, is captured in the first subsection. Subsequently, we present the analysis of existing findings, and structure the design space to meet the objectives of user-informed system adaptation.

2.1. Methodology

The research process we followed was based on a literature analysis. Its findings formed the technological basis and empirical evidence for prototype development. The prototype was tested in the field of home healthcare. We detail each step below. Steps 1–3 comprise the methodology we followed for the literature review. Steps 4–6 refer to the design and implementation of the user-centric artefact.

2.1.1. Literature Review

Step 1: Search for Technological and Empirical Evidence

The literature search on user-centric adaptation in home healthcare has been conducted in English and German, based on keywords including “healthcare”, “home”, “digitization”, “system”, and “architecture”. The various search terms were grouped into five categories: personalization, smart home, healthcare, application systems, and intelligibility (for details of the comprehensive list, see Appendix A). The respective items were then combined in different ways, such as “ambient assisted living” AND “home” AND “prototype” AND “tangible user interface” or “tangible user interface” AND “Internet of Medical Things”.

In the literature search, we examined various databases including Scopus, IEEE, SpringerLink, Google Scholar, Eric, Fachportal Pädagogik, PubMed, and Cochrane Library. Pedagogic databases, such as Eric and Fachportal Pädagogik, were used to better understand the ease of technology adaptation under existing approaches. Domain-specific sources, such as PubMed and Cochrane Library, were searched to find whether medical papers also meet our objective. IEEE was used as a technological library source, in addition to the overarching sources of Scopus, SpringerLink, and Google Scholar.

Step 2: Selection of Papers for Analysis

According to the selected domain, home healthcare systems or prototyping papers focusing on adaptation to users’ needs were of central interest. Scientific rigor was required to perform three selection cycles, in order to identify the final set of papers to be included in our analysis. The first focused on paper titles referring to the home healthcare setting and system development/prototyping. The results of the first selection round were revisited by reviewing the abstracts to ensure all papers on individually adaptable systems were included. Overall, we identified 22 papers in the first round. From these, only seven papers that provided data for analysing user-centric adaptation from empirical and technological perspectives remained for the final analysis.

Although many papers referred to various adaptation concepts for technological systems in general, they mainly considered the technological feasibility of an adaptation concept rather than its evaluation from user tests or empirical validation. However, the paper by the authors of reference [22] was re-examined when developing the prototype, as it seemed suitable for implementing T-Care. It provided validated data on intuitive and easy use.

Step 3: Structured Analysis

To evaluate the papers selected in Step 2, a matrix was created. We used this matrix to document the findings given our research question. We captured the addressed requirements, design process, runtime characteristics in the context of base technologies, user needs, and use cases.

2.1.2. Result Generation

Step 4: Development of Adaptation Concept and Hardware for the Prototype

All the technologies, including Playte [22], as the base for the adaptability concept to be implemented, had to be prepared. A representative set of IoT components for the development of the prototype was selected from the analysis of existing findings. Their combination and the integration with the Tangible User Interface (TUI) then had to be designed. As the base technology for the prototype, a Raspberry Pi was adopted and a database including communication interfaces was created.

Step 5: Development of T-Care Prototype

The development procedure followed a bottom-up strategy. We addressed each IoT component separately, pre-processing its input and controlling the actuators, before combining them. Not all the required sensors could be connected to a single Raspberry Pi unit at the same time. As a Raspberry Pi has insufficient pins to control and process the information of all the required sensors and actuators simultaneously, we had to use three separate computing devices. Further, since the external LCD screen of the Raspberry Pis were unsuitable as user interfaces, an M5Stack (https://m5stack.com, accessed on 5 October 2023) was used instead. The M5Stack could display more characters at the same time and the design of the output would be adapted in a more pleasant way.

Step 6: User Tests

For testing, T-Care domain-specific test cases needed to be defined. We created a questionnaire to collect possible scenarios of use from healthcare practitioners. We asked healthcare professionals to describe candidates for test cases concerning a person’s adaptation needs at home in the context of T-Care. After selecting possible scenarios and running a corresponding pre-test, a field test with three healthcare professionals with different backgrounds was performed. We provided the participants with an information sheet showing the main functionalities of T-Care. After completing the scenario using T-Care, the participants answered an extended version of the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ) [23]. Feedback was finally gathered to make further improvements.

2.2. Literature Analysis

Both the technological and empirical findings of the selected papers have been analysed. For each paper, the study’s purpose, its results, and open issues are provided. Table 1 shows the analysis scheme referring to the technological and empirical evidence, including base technologies, user needs, and use cases, respectively. Hence, we take a closer look at user interventions, beyond the primarily technological features compared to other survey studies, such as in reference [21].

Table 1.

Structure of the analysis.

“Requirements” concern all the necessary equipment and knowledge for using the M-IoT system. The “Design Process” column includes information about the architecture and how the system is constructed and communicates with the user. “Runtime Characteristics” refer to the characteristics, including assistance, and additional tools. “Base Technologies” refer to all the technological evidence of the M-IoT system including technical devices, control possibilities, and notifications during runtime. “User Needs” describe the required user knowledge, adaptation process, user support, and tools for operation. “Use Cases” are the addressed use scenarios captured in the analysed studies, completing the empirical evidence.

In the following, we summarize both types of evidence and conclude, for each study, whether its findings can be directly used for M-IoT developments.

In their work on heterogeneous devices for daily routine monitoring, the authors of reference [24] created an adaptation prototype suitable for working environments, such as technicians/chemists. Although not specifically designed for health conditions, this prototype enables prediction and prevention to detect earlier disorder functionality. The application can be used to monitor daily routines and investigate medical research. The prototype is composed of components that can be worn on the wrist and chest. It can be utilized by users in their residence. Measurable values include temperature, humidity, air pressure, ultraviolet conditions, noise toxic/hazardous gases, indoor and outdoor air quality, heart rate, respiration rate, body temperature, and blood pressure parameters. The configurable platform enables users to monitor diverse ambient, environmental, and physiological parameters. Usability tests concerned real-time configuration, sensor activation, and data measurement, collection, and transmission. All the applied sensors worked reliably, making them candidates for M-IoT developments.

Although the authors of reference [24] did not perform dedicated adaptation tests, they mentioned that healthcare workers could activate/deactivate target sensors and adaptability parameters as well as set up and configure the parameters for each person individually. Sensor activation/deactivation is possible through a smartphone or a graphical user interface (GUI). Given the validation of functionality, the sensors can be used for user-centric M-IoT developments.

The authors of ref. [25] targeted health IoT services for measuring physiological conditions and observing medication adherence. They designed a system to provide home-based healthcare services and optimize the accessibility of medical drugs, although it was not designed for a specific health condition. The addressed scenarios comprised intelligent pharmaceutical packaging (iMedPack), an intelligent medicine box (iMedBox), and a Bio-Patch for measuring the physiological condition of a person. The iMedPack enables a person to access the corrected number of pills that need to be taken at that moment. Therefore, it communicates via passive radio frequency identification with the iMedBox. Furthermore, a Bio-Patch that is worn on the body was designed using inkjet printing and system-on-chip technology. The Bio-Patch detects and transmits the user’s bio-signals to the iMedBox in real time. In the iMedBox, the collected information is stored, interpreted, and displayed on the included tablet. The main functionalities of this system are remote prescriptions, medication reminders, medication non-compliance controls, intelligent analysis, and a first aid alarm.

The application facilitated personalized medication, vital sign monitoring, on-site diagnosis, and interaction with remote physicians. As the feasibility of the system was tested with the IoT components working reliably, all the sensors are possible candidates for further development, such as the T-Care prototype. In particular, the medication reminders and alarm can be used by users in their residence, and be considered for further developments. However, the adaptation of the system was not fully described in the paper, preventing us from drawing conclusions about implementing such a feature. The authors mentioned that a more user-friendly GUI is required to improve the user experience and that the Bio-Patch needs further functional improvements. Hence, new ways for users to interact should be part of M-IoT developments to improve the system’s user-friendliness.

The authors of ref. [2], when looking for unobtrusive IoT sensors for independent elderly people, used different smart objects to create the HABITAT platform, a home care service for domestic and community contexts. A wall light was used for indoor localization, a belt for movement analysis, an armchair for the sitting posture, and a wall panel as a GUI for communication between the user and system. This system was designed to extend elderly people’s autonomy in their own residence. Elderly people with visibility, physical, cognitive, and/or sensory disabilities should also be able to use the system.

The sensors of the devices and beta operating system were tested and turned out to work reliably. Learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors, and satisfaction were analysed and tested for the evaluation. Overall, the assessment was satisfactory. However, the technical aspects were not evaluated during the test phase, as the aim was to verify the overall design and understand its interaction with people. The visual perception of the user interface was found to be pleasant for users. The belt was described as comfortable and the armchair as easy to personalize. The wall light was perceived as adaptable to different domestic contexts and easy to install.

Each sensor/smart object from this study could be used for further development, as the reported tests showed that they worked reliably and that users accepted them. Furthermore, in the testing phase, users were interested in HABITAT and its devices. In terms of requirements, it was mentioned that adding/removing devices should be an effective and easy task as well as that the system should be flexible. However, how sensors/smart objects could be added, removed, or adapted was not described. Users could only change the colours or text size. The authors also reported several suggestions to improve the created devices, such as the armchair and belt.

The authors of ref. [3], to build a platform for individual IoT services, designed the IoT-based Aging-in-Place (AIP) service platform. It supports the use of heterogeneous IoT products. People can efficiently create their own tailored AIP service using the platform. The platform should help patients comply with medication prescriptions. The pillbox is equipped with an NFC (near field communication) tag writer and is placed on its container in the user’s residence. The container is equipped with an NFC reader to read the medication data stored in the NFC tag writer. The medication directions, medication schedule, and information about the pharmacy, pharmacist, and prescription are stored in the pillbox. The pillbox holder (Raspberry Pi with an NFC tag reader) reads the stored information from the pillbox. The collected information is then sent to the AIP platform. The smart app can retrieve all the information on medication routine from the AIP platform. If the suggestion is “take with food”, the system monitors when the user is eating (e.g., when the user is opening the rice cooker) and provides a suitable alarm. The alarms are triggered according to the location of the user in his/her residence via a smartphone, light, speaker, or wristband.

As the functionality of the medication reminder system of the AIP platform has been evaluated and worked well, all the sensors are possible candidates for further development. However, usability and adaptability have not been evaluated. Hence, the usability of the AIP service platform as a composition tool has not yet been proven to be usable by non-IT experts. Furthermore, the authors created the service composition platform for use by medical professionals and informal caregivers. They mentioned the need for a more intuitive way to adapt or create services for older adults. The idea of the rice cooker as an indicator of food intake can be revisited and other everyday objects can serve as indicators, if it is to be used in a country with a different lifestyle. Finally, the authors reported that a more intuitive and user-friendly GUI-based tool was required. Computing devices such as tablets were inappropriate for alerting older adults with mental disorders. Hence, an alternative such as colour-changing room lights or voice-playing commands is needed to help older adults in their everyday lives.

The authors of ref. [6] examined the people-centric monitoring of elderly and disabled individuals. They developed a system for monitoring wheelchair users in their residence that included sensors to detect a fall, environmental evaluation, and ECG and heart rate measurement. The ECG sensor could detect abnormalities in real time. The heart sensor, attached at the wrist of the patient, was used to measure his/her pulse. To detect whether a patient had fallen, a pressure cushion was sewn into the seat of the wheelchair. An algorithm could then detect whether a person had fallen out of the wheelchair. Furthermore, an accelerator sensor was integrated into the wheelchair to detect whether the whole wheelchair was falling. If the wheelchair moved from one room to another, it could receive data from the sensors in the radio reading range of the sink node attached to the belt of the wheelchair user.

For people in wheelchairs such as the elderly and disabled, daily mobile healthcare services are crucial. An intelligent system with real-time monitoring and interacting, tailored to the healthcare of wheelchair users in their residence, has been introduced by the authors of reference [6]. It aimed to overcome the drawbacks of existing home healthcare systems, including their poor mobility, weak interaction, and simple functionality. In a research lab environment, a people-centric prototype was implemented and tested successfully. As the system can interact with the living environment and monitor human activities efficiently, all the sensors are potential candidates for further development. To improve adaptability, the state of the connected devices could be changed through a smartphone. Therefore, the ability to activate/deactivate sensors should be integrated into future systems.

The authors of ref. [26] designed a system for the remote monitoring of patients. This system was designed to not only monitor, but also manage and control diverse types of sensors and IoT medical devices. The study did not mention the health conditions for which this system was designed, as the architecture of the system was the focus. The authors conducted tests with the system. The camera could be turned on and off as needed to monitor the patient. However, how the camera was used (e.g., for detecting falls or something else) was not described. Furthermore, only the performance of the system in combination with the camera was tested successfully.

This study of the control and monitoring capabilities of medical devices considered adapting the system to improve several aspects, including improving the user experience, simplifying the deployment, making setup easier, and adding a remote control. A scalable solution for the management of many sensors and medical devices, and interoperability with different IoT sensors/devices/IP cameras, were also assessed. Effectiveness in real-time eHealth services and utility were measured during the tests. The tests revealed that the developed solution was suitable for remote monitoring and controlling devices, making the components of this prototype possible components for future development. However, usability and adaptability were not tested. In addition, how the user could control the system remotely was not precisely described. The authors only mentioned that it was possible to turn the camera on/off, change the camera angle, and use the camera’s zoom through an active WebRTC session. Therefore, only a browser was necessary. For easy-to-adapt solutions, it is not necessary to include each device to show its functionality. However, which image-based computer vision algorithm the authors used to analyse the camera recordings was not described. Although this algorithm showed the benefits of the prototype, it cannot be embedded in M-IoT developments without further experimentation due to a lack of details.

The system by the authors of reference [27] aimed to create a user-friendly interface for a mobile health app. It contained a developed app based on Android. It was designed for autonomous health management (i.e., home-based health monitoring) rather than a specific health condition. In the prototype, six services were included: health status tracing and 24 h real-time monitoring, emergency care referral and health consultation, home visits, return visit scheduling, prescription delivery, and the delivery of social welfare services. Patients’ vital signs and daily activity data could be monitored and managed by the system through the provided interface, which is useful for clinical staff and the assisted patient. Patients’ physiological data were reported continuously using the cloud-based Telecare Information System. Therefore, the risk of diseases occurring for users in their residence could be effectively monitored. The patient profiles could be used by healthcare professionals to make clinical decisions based on the collected data and degree of illness. A blood pressure gauge connected to a home box and an Android OS smartphone with a user interface were included in the mobile telecare architecture.

Although this study addressed user satisfaction in terms of usability, ease of interface customization, and the availability of plug-ins and function compatibility, it did not describe how the system could be adapted. However, it mentioned that the system could be expanded by adding equipment for measuring physiological information as a patient-centric approach. The tests showed that the system fulfilled the requirements for functional usefulness, ease of learning, information quality, and interface quality. Therefore, all the mentioned sensors are possible candidates for M-IoT developments. In order to assess the effectiveness of platform-based interactions, future work should account for user-informed interface concepts and usability testing.

2.3. Structuring the Design Space

The related work is structured to specify the design space of an adaptable M-IoT system in a user-informing way. Following existing taxonomies of IoT sensor/actuator components, such as that provided by the authors of reference [28], we include sensors and actuators, as given in the previously described technological utility in user residences (technological evidence). Furthermore, the various adaptation approaches used in the analysed work are cross-checked according to their effectiveness for supporting users (empirical evidence).

2.3.1. Sensors and Actuators

The sensors and actuators from the analysed work are summarized to identify relevant sensor candidates for developing an M-IoT adaptation component. The functionality of the sensors and actuators is detailed in the presented scenarios. Additionally, these sensors are categorized by their functionality. Based on this categorization, a set of sensors is selected for further developments. Table 2 summarizes all tested sensors and actuators used by the authors from the analysed work. In this table, the cell of a sensor or actuator contains ‘X’ when it has been used for IoT system development and tested in a use-case scenario successfully. When the possibility of adding further components, such as household products (e.g., by the authors of reference [6]), was mentioned, but not included in the tested scenarios, these products, sensors, and actuators have not been included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of the sensors and actuators used in the analysed studies.

Furthermore, some authors used fully implemented devices, such as a smartwatch with different sensor functionalities included. For instance, the authors of reference [24] used, among other devices/sensors, a fully implemented smartwatch that included various elements. In these cases, the functionalities of such products are mentioned in terms of its sensors (thermistor, accelerator, heart rate sensor, ECG). If sensors and actuators from devices (e.g., a smartphone) are specifically mentioned in the paper and necessary for the tested use case scenario of the authors, they are also mentioned in Table 2. The display from the authors of reference [24] is only included because it is integrated into their developed hardware prototype Ubiqsense and there is no possibility of interacting with this display. However, it converts an electrical input command into an output, according to the definition of actuators used by the authors of reference [29].

The iMedPack [25] can dispense the required number of pills through CDM (a special glue), an RFID reader, and a 10–50 V DC voltage. As the iMedPack is a self-created device and its functionality does not belong to any other off-the-shelf components, it is not mentioned in Table 2. Ref. [25] also mentioned that the air conditions are measured for the test scenario. While the air conditions are not precisely described, smoke, humidity, and temperature detection are mentioned explicitly. Therefore, air conditions are not included in Table 2.

The authors of ref. [27] used a home box in combination with a blood pressure gauge. Data processing happens on a smartphone, advanced data processing occurs in the cloud, and a smartphone is used as a user interface. However, the role of the home box remains unclear—it was only mentioned that it is used to enhance data mobility. Therefore, it could be used to transmit data from the blood pressure gauge to the smartphone.

To decide which sensors should be used for developing the M-IoT prototype T-Care, the sensors are first categorized. The authors of ref. [24] categorized the sensors used in their study according to their area of functionality: environmental and physiological measurements. This approach is expanded so that the sensors from other studies can also be assigned to a specific category. According to their functionality, the following categories are derived:

- Physiological sensors: Heart rate, ECG, EEG, skin temperature, respiration rate (interval), blood pressure gauge

- Environmental sensors: Air temperature, smoke sensor, gas sensor, air humidity, air pressure, UV, NO2, noise sensor

- Sensors for data exchange: RFID, NFC

- Force transducer sensors: Weight sensor, load cells pressure cushion

- Movement detection: Ultrasonic sensor, proximity sensor, IR sensor, accelerator, intertial sensor

- Image Processing: Camera

Furthermore, the actuators are categorized according to their position relative to the body of a person. Therefore, some actuators need to be worn by the person, whereas others require the person to be next to a stationary system or device to recognize reminder signals:

- Close Distance: Vibrating motor, display

- Wide Distance: Light, beeper, speaker

For developing a showcase for an easily adaptable home healthcare system, such as T-Care, we did not include all the sensors and actuators mentioned in Table 2. To exemplify effective adaptability, at least one sensor and actuator from each category has been used. Some of the sensors could not be considered because they were self-developed by the authors and no off-the-shelf components are available. Moreover, since the camera needs a considerable amount of memory space for images and videos, and we are interested in a lean approach, it was not chosen for developing the showcase. The selected sensors for T-Care are highlighted in color in Table 2.

2.3.2. Adaptation Concepts

According to the objectives of the study, we also needed to structure the analysed findings according to the characteristics of user-centred adaptation features. The variants of how adaptation has been understood using existing approaches can be either termed as adaptable/flexible, people-centric, individual-based, or expandable. Table 3 summarizes the authors’ understanding of the system capabilities needed to adapt to users’ and situational needs.

Table 3.

Adaptation context as described by the authors.

When referring to adaptability, the authors of reference [2] denoted IoT services that have the capability to meet the different expectations of users. Such services require flexible feature arrangements that can be organized according to the skills and requests of users, thereby leading to successful product use. The term people-centric was used by the authors of reference [6], who developed a monitoring system for elderly and disabled individuals using wheelchairs at home. According to them, focusing on people requires sensors and actuators that provide human-centred interaction and system feedback, such as comfortable IoT body devices; further, sensitive care must be taken through the convenient measuring of pressure using cushions in the wheelchair. Although not explicitly termed individualized, people-centric approaches could be counted as individualized, similar to the other analysed approaches. Referring to enrichment and dynamic development, expandable adaptation was mentioned as a design concern by most authors.

It can be concluded that the foci of adaptation were on the individual user and on the extension of a system with further IoT components and services to provide more convenience to users.

3. Results

After having prepared the design space in terms of structuring the currently applied technological components and the concepts of user-centred adaptation, a lean showcase can be developed. In the following, we detail its architecture and context of use, before reporting on the performed user tests.

3.1. T-Care: M-IoT Prototype for User-Informed Home Healthcare

Previous architectures and concepts are extended towards the user-informed adaptation of a healthcare showcase to be used in user residences. Taking a step forward, we propose a Tangible User Interface (TUI) approach for adaptation. In this way, we implement a more user-friendly user interface to improve the user experience [25]. It should also provide a more intuitive way to adapt or create services for older adults [3]. Its capabilities need to be tested with respect to usability (cf. [27]), as reported later on in this section.

3.1.1. User Interface

TUIs have already been explored in the literature in different contexts. The authors of ref. [30] stated that, through TUI systems, the experience of students in higher education is enhanced in comparison to traditional lecturing. The authors of ref. [31] highlighted that the knowledge gain through a TUI in learning IoT concepts is considerable. Furthermore, the authors of ref. [32] studied the ease of use of a TUI for an educational game with two versions, one with a TUI and one with PC interaction. The results of this study suggested that the tangible version of the game was easier for children to use.

Ref. [33] showed that tangibility helps test subjects aged 16 to 40 years achieve a higher learning gain and perform tasks better. The TUI provided the user with a strong feeling of directness and problem solving and was considered as playful. Additionally, exploratory behaviours were also encouraged through tangibility. Ref. [34] showed that a TUI is preferred over a GUI by users aged 19 to 31 years, as it provides rich feedback, produces high levels of realism, and enables physical interaction. The test subjects in the study called the TUI enjoyable and stimulating.

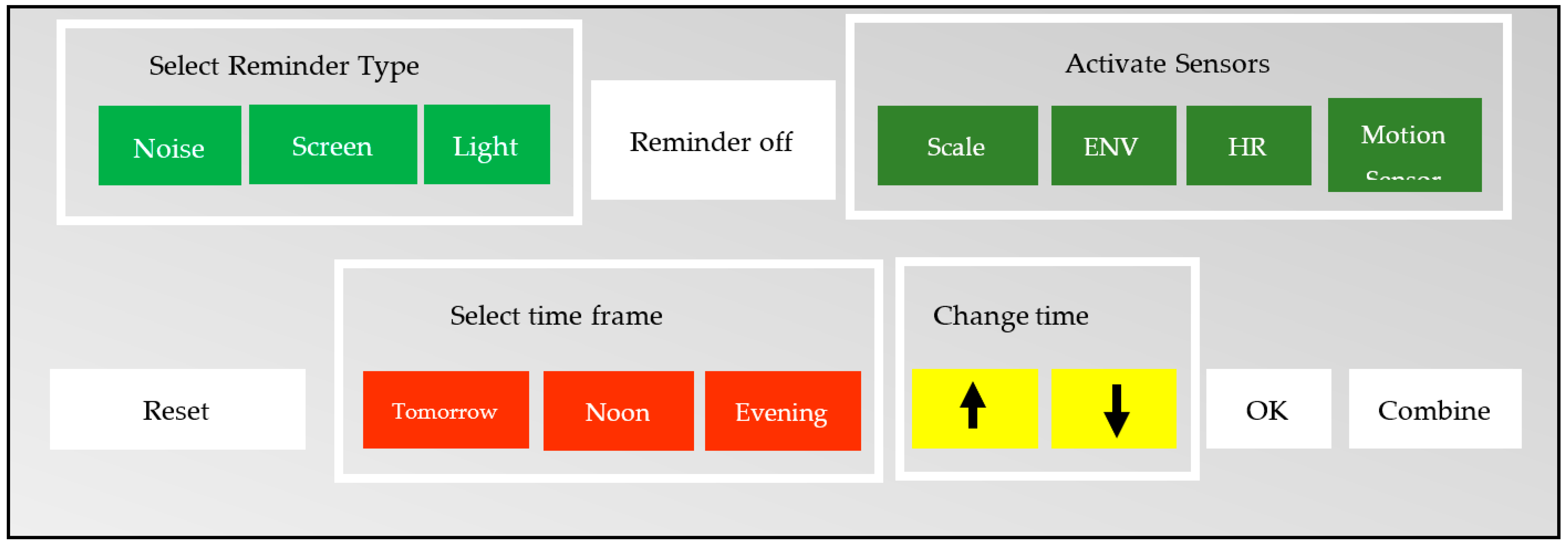

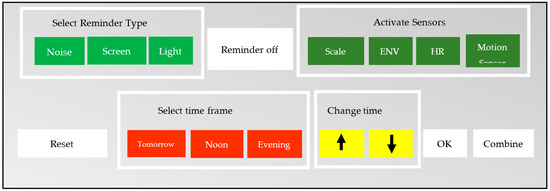

The authors of ref. [7] mentioned that elderly people’s needs are often neglected in mainstream technology. A TUI should thus help them bridge the gap between the physical and digital worlds by providing a more natural and intuitive interaction with the system. Ref. [20] proved the ease of use of TUIs for elderly people. The findings led to the conclusion that TUIs can be effectively used for the user-centred adaptation of M-IoT applications. Consequently, T-Care’s TUI concept is based on Playte [22], enabling M-IoT-relevant interaction buttons. A total of 16 buttons were required to provide the necessary functionality—see Figure 2. They are marked green, white, brown, red, and yellow, and grouped according to user-centred function categories.

Figure 2.

TUI concept representation for implementing T-Care using Playte.

3.1.2. Functionality

T-Care aims to help a patient in his/her residence take the required medication at the right time. Therefore, the user can change the time of the reminder to fit individual needs. Furthermore, he/she can also activate different kinds of actuators for the reminder (e.g., via a loud sound, a light, or a message on a screen). These reminders can also be turned off using the “reminder off” button. In addition, the system enables the activation of different sensors. A scale, an environment sensor, a heart rate sensor, and a motion sensor can be activated or deactivated by pressing the according buttons. Through the “reset” button, it is possible to reset all the reminder settings to the default settings saved in the system. Finally, the “combine” and “OK” buttons enable the changing of the time and kind of reminder.

We selected specific places for the buttons because Playte mostly used similar places for similar functionalities. Hence, behaviors can be activated and deactivated using the slots in the first row of Playte. Therefore, the activation of the kind of reminder and activation/deactivation of the sensors is placed in the first row, too. In addition, the button to stop an active reminder is placed in the first row.

The “combine” functionality of Playte is used for the TUI of T-Care as well. Since it does not work with small plastic bricks that can be programmed, this functionality is replaced by pressing buttons in a specified order. After pressing “combine”, users are required to select a time; afterwards, either the arrows to adapt the reminder time or one of the actuators to change the kind of reminder must be pressed. The “OK” button ends a combination process.

Finally, the TUI allows users to reset the system to the default settings. The T-Care user interface supports the following adaptation activities:

- Activate/deactivate different sensors for monitoring and control: Scale, Environment sensor, Heart rate sensor, Motion sensor;

- Change medication reminder settings: Change kind of reminder (buzzer, screen, light), Change time of reminder;

- Turn off the reminder;

- Reset reminder settings to the default settings.

When starting T-Care, it is necessary to put the pillbox on the RFID reader. The bottom of the pillbox contains an NFC tag, which is read by the RFID reader and compares the ID with the ID values from a database of the values of the default settings for the medication intake. This means it includes the name, kind of reminder, and time of day that the medication must be taken. Through these default settings, the system is configured by the database automatically. Afterwards, additional adaptations can be made. The TUI enables activating a scale, the environment sensor (ENV), heart rate sensor (HR), and motion sensor by pushing a button; these are deactivated when the button is pushed again.

- Scale: If the scale is active, the medication can be placed on the scale sensor. The scale then measures the weight of the medication and senses whether the patient is taking his/her medication accordingly. It measures the weight difference before and after the pills are taken. Both values are stored in a database.

- ENV: The environment sensor measures the temperature and humidity of the environment. It measures these values, at the time of activation and, once set active, every hour, and saves them in the database.

- HR: The heart rate sensor measures the heart rate of the patient when he/she places a finger on the sensor, and saves the values in the database.

- Motion: The motion sensor can recognize whether a person is located in a room and moving around. If this sensor is active and the light reminder for medication intake starts, the buzzer will also start, even though it was not activated manually by the user. However, if the patient is not in the room and not next to the system, he/she will not recognize the reminder. Therefore, if the patient is in another room and the motion sensor realizes that, it will activate the buzzer as a reminder.

Furthermore, some buttons have a special functionality. Of these, “combine” is the most important, as it can be used to change the reminder settings.

- Reminder off: When a reminder is active, it can be turned off by pushing the “reminder off” button.

- Combine: The “combine” button is used to change the medication time or kind of reminder. Once the time is selected, the kind of reminder can be set by pushing the buttons for the buzzer, screen, or light. It is possible to select one, two, or all three options. Additionally, it is possible to select one of the arrows on the TUI to change the time.

- OK: The “OK” button (as mentioned above) is pressed after setting the time or changing the kind of reminder. Once the “OK” button is pressed, the new settings are saved in the database.

- Reset: If it is required to return the settings for a medication reminder to the default settings, the “reset” button needs to be pressed.

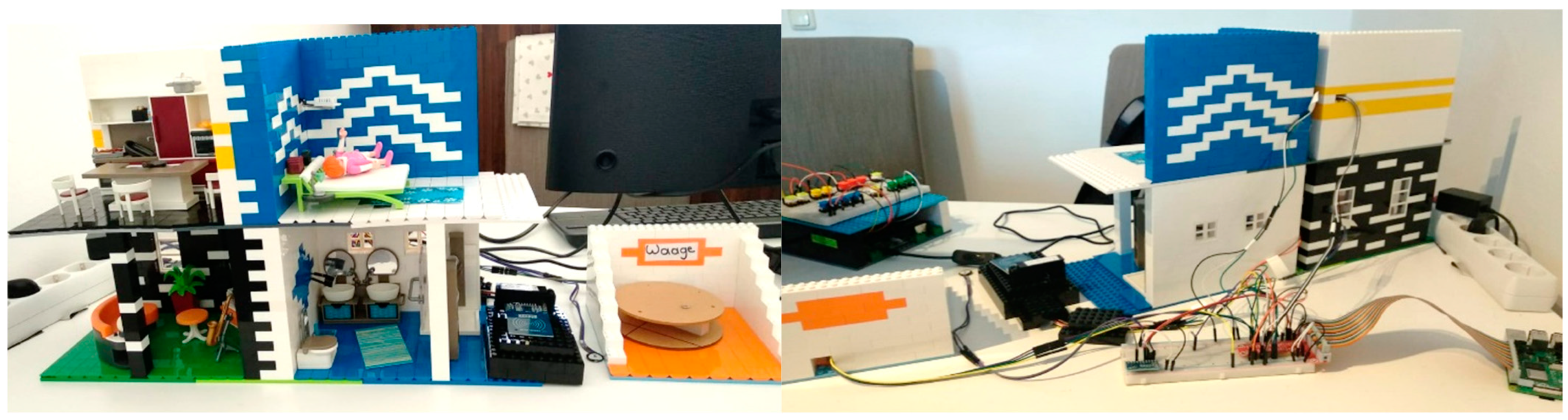

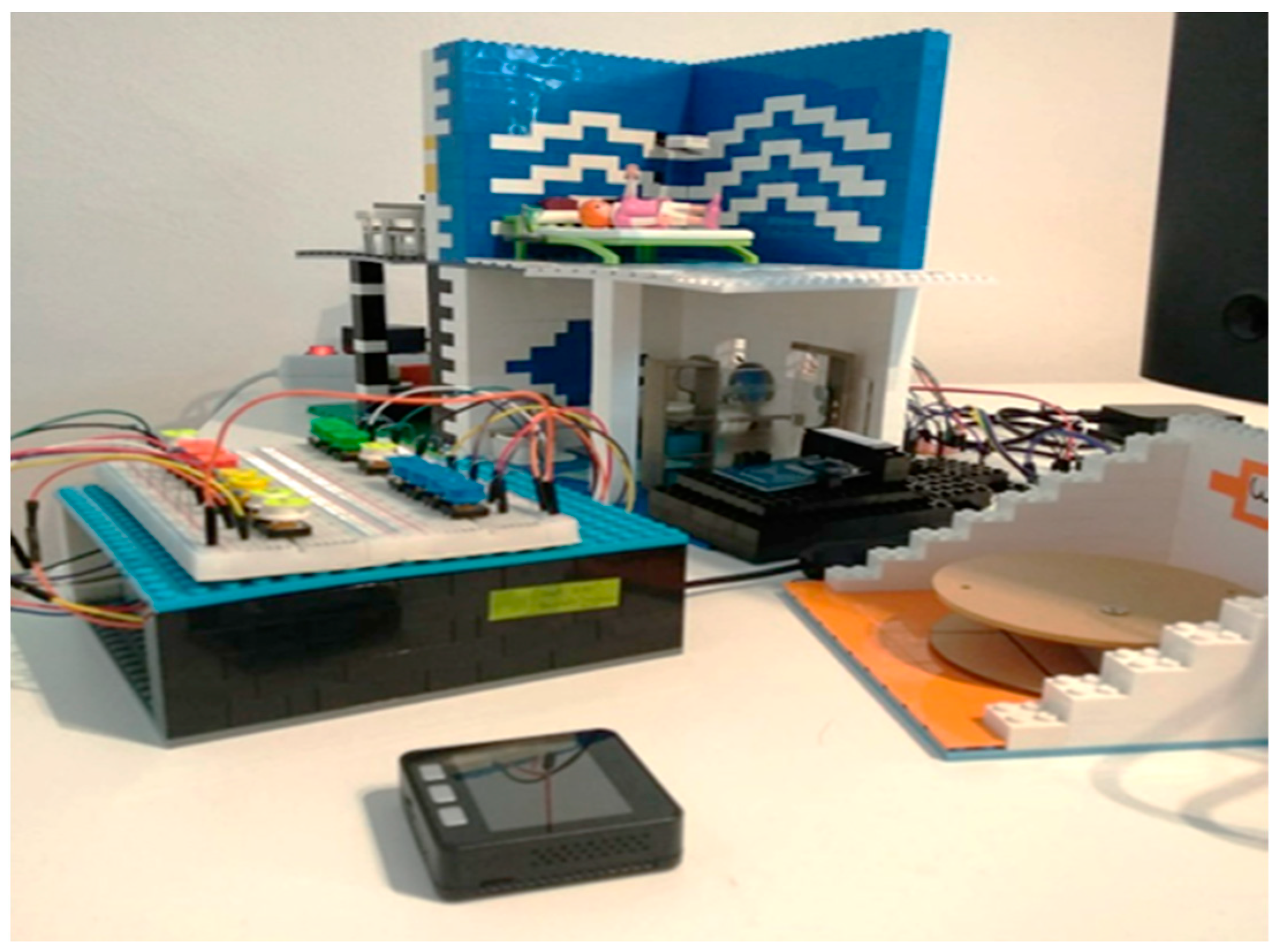

In Figure 3, T-Care is depicted, as it was finally used for the user evaluation. The T-Care sensors and actuators were placed in a house of small plastic bricks to help testers better understand the usage in a patient’s residence.

Figure 3.

T-Care test setting.

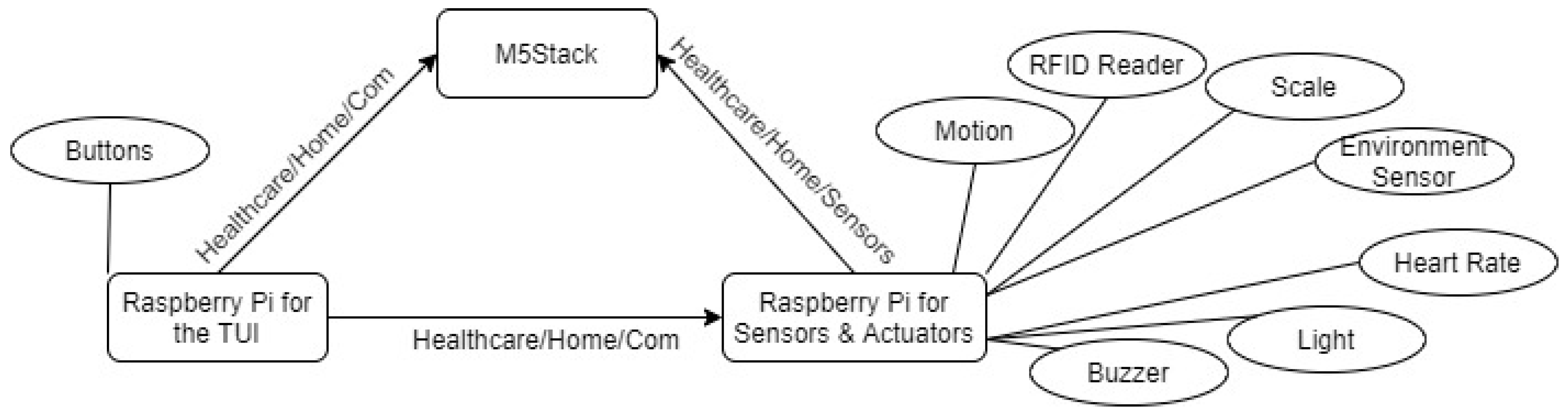

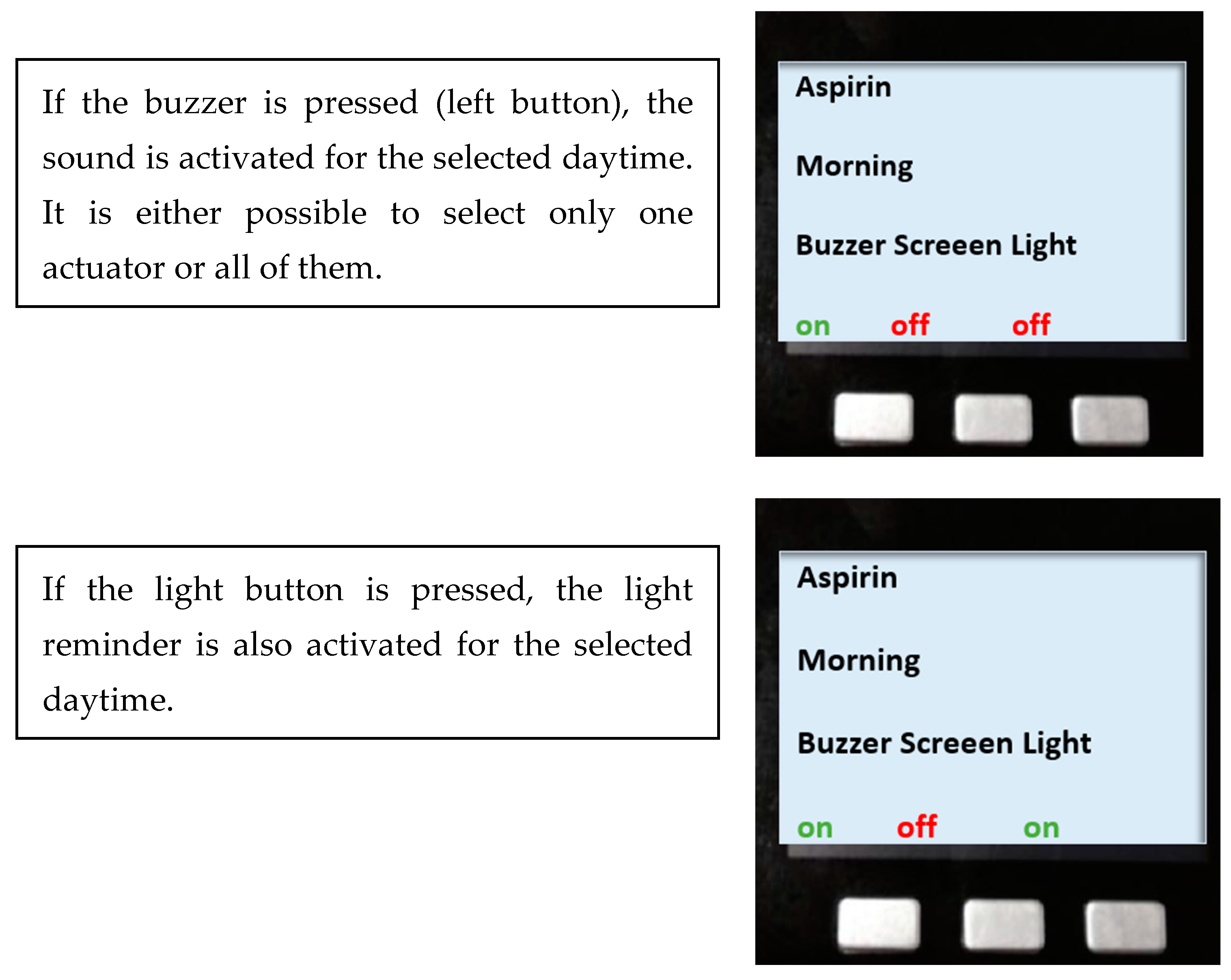

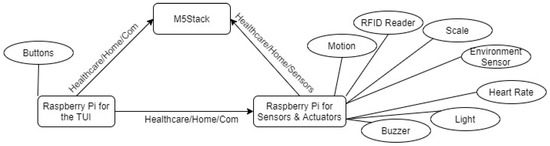

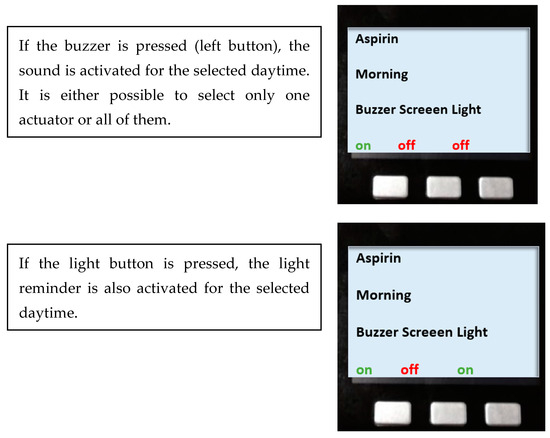

Figure 4 provides an overview of the computing devices, sensors, and actuators. It illustrates the communication, showing which sensor and actuator is connected to which coordination device (Raspberry Pi). Furthermore, this figure also illustrates the communication paths between the Raspberry Pis and M5Stack (https://m5stack.com/ - accessed on 5 October 2023) via MQTT. The M5Stack controller contains the interface of T-Care. It gives the user feedback and shows the values of the sensors and the pressed buttons. Figure 5 shows a sample combination of sensors and its control from the user’s adaptation perspective. The medication Aspirin has to be taken in the morning. The display shows which buttons are activated. The upper part of the figure shows the buzzer active as a reminder and the lower part the light active as an additional reminder.

Figure 4.

Overview of the components of T-Care and communication paths.

Figure 5.

Sample M5Stack sequence handling the combination of sensors.

Technologically, each button is connected to a different PIN of the Raspberry Pi, either through a 10 k or 1 k resistor to 3.3 V pin. The TUI requires libraries to be installed, such as Paho mqtt, in order to publish the text messages to the MQTT broker, after connecting the buttons to the Raspberry Pi. MariaDB is used as a mysql database. In a log_buttons table, the activation of each button is stored. It helps analysing the user behavior when interacting with the system. Based on these data, recommendations for users can be derived.

3.2. Field Study

To assess the usability of T-Care, the prototype has been tested and its usefulness assessed. Beforehand, a pre-test with a healthcare professional was conducted to check whether the test items are easy to understand and the prototype is usable with respect to its functionality and error handling. This pre-test led to minor changes to the prototype, the information sheet provided for the tests, and the way test subjects are introduced to the prototype. Afterwards, three further healthcare professionals were asked to test T-Care in the scenarios of use selected from a preliminary survey. Such an initial step generates authentic domain knowledge, and enhances the credibility of user tests. In Appendix B, the questionnaire of the preliminary survey for scenario selection is detailed.

3.2.1. Pre-Test

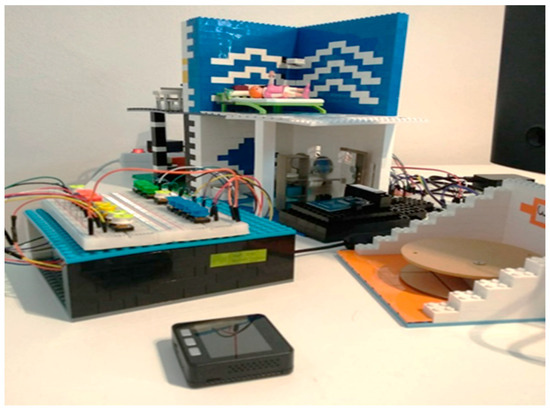

The healthcare professional understood the scenario and test items without further explanation and stated that they are easy to understand and self-explanatory. The pre-test scenario corresponded to the one used in the second user test later on. The healthcare professional was asked to set up the system, so that a patient with this disease and the required medication could adapt it to individual needs—see the setup depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Pre-test setup.

The selected scenario is described below:

Disease: epilepsy. Treatment at home:

- Medication: Antiepileptics twice a day (08:00 and 20:00 h).

- Vital parameter: Monitoring device with Sao2 and pulse. During a seizure, a drop-in saturation can be detected and O2 can be administered if necessary.

- Methods/tools: Mobile phone app on which the time can be quickly stopped with one click during a cramp event and in which a history is then created. Furthermore, the strength and various cramp symptoms can also be entered. A pulse oximeter provides an alert in the case of a drop-in saturation.

The healthcare professional was verbally introduced to the usage of the system and its functionality. Additionally, an information sheet was provided in case something remained unclear. The test phase with the prototype finished successfully, as the tester was able to set up the system accordingly. However, some misunderstandings led to a change in the explanation of the usage, the information sheet, and in the prototype as described below.

After setting up the system successfully, the healthcare professional was asked to answer the PSSUQ, including a complementary item about the additional functionalities the prototype should provide (see Appendix C). The answers of the PSSUQ were evaluated according to reference [23]. There was one major problem with the questionnaire in the pre-test. In the PSSUQ, which number meant strongly agree and which strongly disagree was unclear. Consequently, the pre-test was answered mirror inverted. It was explained to the tester that 1 meant strongly agree and 7 strongly disagree. Afterwards, the test subject corrected the answers. For the actual tests, the categories were marked accordingly to prevent such a misinterpretation. The evaluation of the PSSUQ provided the following results: Overall Satisfaction Score: 1.5, System Usefulness: 1.29, Information Quality: 1.43, and Interface Quality: 1.67.

In the course of the pre-test, a problem occurred when activating the sensor. The initial explanation did not make it clear that it was not required to press “combine” before the sensor button can be pressed. Therefore, an error message was added to make subsequent users aware of this.

Some problems would not have occurred when the additional information sheet had been read. Therefore, the introduction was changed for the subsequent tests, so that test subjects needed to read the information sheet before the system was explained to them verbally.

Using the PSSUQ required adjusting the explanation of the system demonstrating some functionalities. Furthermore, there were technical problems with the scale, as the explanation did not mention that the scale needs some time to prepare itself, and the medication needs to be placed on the scale accordingly. The respective information was added into the information sheet to avoid this problem in the future.

The changes mentioned above were all applied before the three test subjects tested the prototype and answered the questionnaires.

3.2.2. User Tests

First test case. The test items were mailed to a male nurse before the test. For the test subject, it was clear how to address the items. Therefore, he never asked any questions and returned the answered questionnaire with the scenarios.

Disease: psychosis. Treatment at home:

- Medication: take medication (depot neuroleptics) at both 08:00 and 19:00 h every 2 to 4 weeks.

- Vital parameter: measure body temperature.

- Methods/tools: Reminder for the medication intake, reminder for the appointment with the doctor regarding depot syringe.

Second test case. Test items were mailed to another male nurse before the test. As he was unclear about how to answer some questions, the nurse asked for an example addressing the scenario. After some exemplification from the first user test, another scenario (see below) was sent to him. Now, he was able to complete the user test without further questions.

Disease: epilepsy. Treatment at home:

- Medication: Antiepileptics to be taken twice a day (08:00 and 20:00 h).

- Vital parameter: Monitoring device with Sao2 and pulse. During a seizure, a drop-in saturation can be detected and O2 can be administered if necessary.

- Methods/tools: Mobile phone app on which the time can be quickly stopped with one click during a cramp event and in which a history is then created. Furthermore, the strength and various cramp symptoms can also be entered. A pulse oximeter provides an alert in the case of a drop-in saturation.

Third test case. The test items were initially mailed to a nurse in a retirement home. Although she answered the questionnaire, she added that none of the patients could look after themselves in her workplace. As this was a requirement described in the questionnaire, she turned out to be an unsuitable test subject. Therefore, another nurse was asked to test T-Care. Although she was working in an operating room, with little information about patients’ needs at home, she could use her knowledge from an earlier internship for addressing the items of the first test case.

Disease: psychosis. Treatment at home:

- Medication: take medication (depot neuroleptics) at both 08:00 and 19:00 h, every 2 to 4 weeks.

- Vital parameter: measure body temperature.

- Methods/tools: Reminder for the medication intake, reminder for the appointment with the doctor regarding depot syringe.

3.2.3. Test Results

We report the empirical findings in the context of each use case according to the collected data. Our observations of the test subjects using T-Care highlighted some problems with usage. The first test subject had problems using the “OK” button, as he also pressed “OK” after he had activated/deactivated the sensor. The second test subject seemed unsure about using the “combine” button. She spoke out loud the next steps she wanted to carry out and waited until this information was confirmed. During the test with the second test subject, the Raspberry Pi for the sensors and actuators paused a programme and therefore, the background settings were not set. However, this problem only occurred once. The test subject was asked to reset the system. During the resetting, he seemed more interested in the possible settings of the system, as he also turned the sensor for motion and environment on and then off. He first turned them off, as he did not think they were helpful for the scenario. At the end, he unintentionally pressed the wrong button (“reset” button), which led to confusion because the screen of the M5Stack no longer displayed any messages.

The third person also had trouble with the “combine” button. Sometimes she pressed it without knowing the next steps. For instance, she pressed “combine” before she pressed the “scale” button. Additionally, she wanted to set the scale for a specific time. However, the scale can only be activated or deactivated; afterwards, it measures the weight of the medication the whole time, if active.

Overall, two of the three test subjects had problems with using the “combine” button. One had problems using the “OK” button, but this incorrect use had no negative effect on the system. Furthermore, the scale caused some trouble, as the third test subject was not confident in using it. She wanted to set the scale for a specific time. In the course of testing, the subjects became more confident using the T-Care functionality. This is also reflected by the PSSUQ results in Table 4.

Table 4.

PSSUQ results.

Concerning the PSSUQ scoring, the worst result is 7 and the best result is 1. The overall satisfaction score is below 2 for each of the test cases. Regarding the subcategories (system usefulness, information quality, and interface quality), information quality always received the highest value and interface quality the lowest. Interface quality was always rated below 2.5, leaving room for improvement.

The first subject mentioned that if the TUI had been covered in a case, he would have rated it with a higher score. Furthermore, the colours of the buttons and structure of the TUI were mentioned in a positive way by two of the test subjects. Therefore, it can be concluded that the colour system of the buttons should be kept while covering the wires for the buttons would set up a more appealing design.

3.3. Discussion

The increasing need for an easy-to-grasp and individualized user support system in M-IoT home healthcare has led to the introduction of a TUI for the developed T-Care system. The user-centric adaptation facilities have been based on performing an in-depth analysis of empirical IoT findings. Although a variety of contexts and approaches to adaptation exist, existing approaches mainly considered the technological feasibility of an adaptation concept rather than its evaluation from user tests or empirical validation. To answer our research question of “How can home healthcare systems be created that can be adapted to support people with different needs?”, the developed adaptable user support should ensure a natural and intuitive interaction with the healthcare system in the course of adaptation.

The selection of sensors operated via the TUI corresponded to the set of IoT devices successfully applied in the field of medical user support (cf. [35]). We also followed the strategy to capture the practice of professionals working with patients to contribute to better interventions or post-interventions in the residence (cf. [36]). As such, we could implement a holistic M-IoT approach, as suggested by the authors of reference [37]: “The human experience in healthcare integrates the sum of all interactions, every encounter among patients, families and care partners and the healthcare workforce. It is driven by the culture of healthcare organizations and systems that work tirelessly to support a healthcare ecosystem that operates within the breadth of the care continuum into the communities they serve and the ever-changing environmental landscapes in which they are situated.” (p. 16).

Three healthcare professionals could test a scenario about the common treatment patients conduct at home to recover from their disease or treat it in the best way possible. Overall, all of them were able to successfully adapt the system. However, at the beginning, some of the functionalities of the TUI were unclear and they needed to ask questions about its usage. After using T-Care, they answered the PSSUQ. The results of this questionnaire showed that all the test subjects were satisfied with the usage of the prototype, including critical design elements, such as the visualization of data (cf. [38]), and user-centred evaluation (cf. [39]) through authentic scenario definitions.

The scores in the PSSUQ could have been influenced by the prototypical design of the TUI, as it was not embedded in an attractive cladding. If the TUI had a more appealing case, the scores could have been higher. For further tests, it is recommended to build more appealing cladding. Furthermore, additional functionalities would be helpful according to the test subjects. For example, they expressed a wish for further reminders for weekly/monthly medication, appointments with the doctor, and measuring vital parameters. In that case, further design aspects, like privacy, will have to be tackled (cf. [40]).

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, further testing, e.g., in the course of an event with senior adults from a seniors’ association, was not possible. Hence, further studies should aim to test usability with seniors to adapt M-IoT systems in the course of operation, i.e., after healthcare professionals have configured it according to the individual medical prescription.

4. Conclusions

Since IoT applications in the domain of healthcare continuously propagate to people’s homes, user control becomes an immanent socio-technical system property, like other Internet-of-Behavior developments [41]. Users increasingly need to be informed of how to adapt medical IoT (M-IoT) applications to their individual needs. This study aimed to find out which M-IoT components and adaptation concepts could be effectively used for adaptation. Hence, exploring the user-centric adaptation facilities of M-IoT systems in the context of home healthcare led to a research methodology analysing technological and empirical evidence of user-informed M-IoT adaptation.

Given the results from both analyses, we propose a Tangible User Interface (TUI) to meet the quest for easy-to-adapt M-IoT applications. It informs users of the use and state of sensors and actuators for individualizing the settings according to their home healthcare needs. The developed device has been tested in an authentic environment after eliciting domain-specific scenarios from healthcare workers. The involved users experienced the application as useful in adapting the system to the daily medication routines of patients, and suggested improvements with respect to the intuitive use of the buttons designed for control and adaption. In particular, the combination of functions requires further studies.

Future work will have to overcome the limitations with respect to the Playte platform and allow for arranging control components dynamically. As such, future studies will not only focus on the user experience of tangible IoT application (cf. [42]) to increase user IoT competences, but also follow model-based approaches to the user-centred development of Cyber-Physical Systems. It qualifies users as designers that specify system behavior for further engineering [43]. The benefit of design-integrated engineering concerns the automated execution of system models, which enables direct user experience and task-specific feedback. Once metaverse applications propagate to user routines and healthcare (cf. [44]), model-based design-integrated engineering is a promising candidate for participatory development [45].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F. and C.S.; methodology, H.F. and C.S.; software, H.F.; validation, H.F.; formal analysis, H.F. and C.S.; investigation, H.F. and C.S.; resources, H.F. and C.S.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, H.F.; writing—review and editing, C.S.; visualization, H.F. and C.S.; supervision; project administration, H.F. and C.S.; funding acquisition, H.F. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All the answered questionnaires on the preparation of the field study and test subjects are in the following Google Drive folder. Furthermore, this also includes all the created algorithms for T-Care. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ngsu-TQpz6NXsd3Rtgnfy4e-C3Rm7CQz?usp=sharing (accessed on 5 October 2023).

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by a personal research university grant awarded to Hannah Fehringer. Open Access Funding by the University of Linz.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Terms of the Literature Search

A comprehensive literature search was conducted with search terms divided into five categories: individually adaptable, home, healthcare, system, and easily understandable. The items used for these categories are listed below—the search included German and English terms:

Individually adaptable: personalized, adaptable, user-centered design, user-centered, usability, customized, scenario-based design, dynamic, person-centered, personalisiert, user experience, personenzentriert, anpassbar, adaptierbar, individuell, adaptieren, Benutzerinteraktion

Home: in-house, ambient assisted living, In-Haus, zuhause

Healthcare: IoMT, Internet of Medical Things, healthcare, eHealth, MCPS, medical Cyber-Physical Systems, Gesundheitswesen, Internet der medizinischen Dinge, medizinisches cyber-physisches System, medizinisches System

System: prototype, CPS, Cyber-Physical Systems, App, system, wearables, technology, IoT, Internet of Things, monitoring, monitoring system, sensor, development board, development, Internet der Dinge, Prototyp, Digitalisierung, tragbare Sensoren, Technologie, Entwicklung.

Easily understandable: tangible, physical programming, Tangible User Interface, TUI, tangible user adaption, Human–Computer Interaction, touchable, tangible coding, tangible programming interface, Benutzungsschnittstelle, berührbare Programmierung, Benutzeroberfläche.

Appendix B. Questionnaire for Scenario Identification

These items were originally provided in German and translated into English:

- Which field(s) did you study for your current job in the health sector?

- What is your current job title?

- In which area are you currently working? Name the ward where you work or important characteristics of your field of activity.

- How long have you been working in this profession? It is sufficient to state the period of employment in half-year increments, e.g., 1.5 years.

- Have you had other professional experience in the health sector before? In the case of multiple work experiences, please answer the following questions about your work experience and clearly mark which profession is meant by your answers. If yes, please answer the following questions. If not, you can continue with the details on the use cases.

- In which area(s) did you work?

- How long were you employed in the activity or activities mentioned? It is sufficient to state the activity in half-year increments, e.g., 1.5 years.

- What was/were your exact job title/s?

- Do you have previous experience with adaptivity or IoT elements (e.g., Raspberry Pi)?

Details for Your Use Cases

This research is about supporting patients in their recovery and medical treatment at home. As diseases of different patients progress differently and those patients also need different types of support, the created prototype should be adaptable to patients’ needs. To ensure this adaptability, the system is equipped with an interface that allows it to be customized.

After developing the prototype, we need to check whether the prototype can also be used in real-life settings. We need information from you about the activities patients often have to carry out at home after a hospital stay to recover. This can be ...

… that certain medications must be taken once or at certain intervals.

… that certain devices/systems/sensors for measuring vital parameters must be used frequently by the patient at home (especially heart rate monitors or others), including how they are meant to be used.

… that certain tools have been provided (e.g., reminder tools, apps).

… that certain environmental parameters need to be measured.

Please do not include physical exercises in your selected use cases (e.g., necessary during/after physiotherapy). Likewise, the patients in your use cases should still be able to move for self-care. It is also important to give a rough description of the patient’s clinical picture from this case. A rough description, such as ‘the patient had an infection’, is sufficient.

A use case can consist of several objects, sensors, or devices that have to be used by the patient at home. Thus, for example, several medications can be specified in combination and certain vital parameters can also be monitored. Your selected use cases should occur regularly in everyday hospital life.

Take time to think about what you have encountered most often in your career so far.

1. Scenario:

Clinical picture of the patient:

Treatment at home:

Medication(s):

Vital parameters:

Methods/tools:

2. Scenario:

Clinical picture of the patient:

Treatment at home:

Medication(s):

Vital parameters:

Methods/tools:

3. Scenario:

Clinical picture of the patient:

Treatment at home:

Medication(s):

Vital parameters:

Methods/tools:

Appendix C. PSSUQ

The following questionnaire gives you an opportunity to tell us your reactions to the system you used. Your responses will help us understand what aspects of the system you are particularly concerned about and the aspects that satisfy you.

Think about all the tasks that you have carried out with the system while you answer these questions. Please read each statement and indicate how strongly you agree or disagree with the statement by circling a number on the scale. If a statement does not apply to you, circle n/a.

Please write comments to elaborate on your answers. After you have completed this questionnaire, we will go over your answers with you to make sure we understand all of your responses.

Thank you!

Strongly Agree = 1

Strongly Disagree = 7

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | n/a | Comments | |

| Overall, I am satisfied with how easy it is to use this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| It was simple to use this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| I could effectively complete the tasks and scenarios using this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| I was able to complete the tasks and scenarios quickly using this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| I was able to efficiently complete the tasks and scenarios using this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| I felt comfortable using this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| It was easy to learn to use this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| I believe I could become productive quickly using this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| The system gave error messages that clearly told me how to fix problems. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| Whenever I made a mistake using the system, I could recover easily and quickly. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| The information (such as on-screen messages and other documentation) provided with this system was clear. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| It was easy to find the information I needed. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| The information provided for the system was easy to understand. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| The information was effective in helping me complete the tasks and scenarios. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| The organization of information on the system screens was clear. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| The interface of this system was pleasant. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| I liked using the interface of this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| This system has all the functions and capabilities I expect it to have. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| Overall, I am satisfied with this system. | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

Are there functions that would still be helpful for using the system at home or for the scenario supported that are not currently included?

References

- Banafa, A. Secure and Smart Internet of Things (IoT); River Publishers: Delft, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9788770220309. [Google Scholar]

- Borelli, E.; Paolini, G.; Antoniazzi, F.; Barbiroli, M.; Benassi, F.; Chesani, F.; Chiari, L.; Fantini, M.; Fuschini, F.; Galassi, A.; et al. HABITAT: An IoT solution for independent elderly. Sensors 2019, 19, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, S.; Sung, N.-M.; Ahn, I.-Y.; Ryu, M.; Yun, J. Building IoT services for aging in place using standard-based IoT platforms and heterogeneous IoT products. Sensors 2017, 17, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Rahman, S.; Sadia, H.; Perwej, Y. A holistic analysis of Medical Internet of Things (MIoT). J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2021, 11, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugon, A.; Séroussi, B.; Lovis, C. (Eds.) Transforming Healthcare with the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the EFMI Special Topic Conference 2016, Paris, France, 17–19 April 2016; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 221. ISSN 0926-9630. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Ge, Y.; Li, W.; Rao, W.; Shen, W. A home mobile healthcare system for wheelchair users. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 18th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), Hsinchu, Taiwan, 21–23 May 2014; pp. 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, W.K.; Chen, W.; Bergland, A. Tangible user interface for social interactions for the elderly: A Review of literature. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 2018, 7249378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Alshahrani, H.; Rajab, A.; Shaikh, A.; Song, H.; Farouk, A. QoS review: Smart sensing in wake of COVID-19, current trends and specifications with future research directions. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 23, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajagbe, S.A.; Awotunde, J.B.; Adesina, A.O.; Achimugu, P.; Kumar, T.A. Internet of medical things (IoMT): Applications, challenges, and prospects in a data-driven technology. Intell. Healthc. Infrastruct. Algorithms Manag. 2022, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherifi, A.; Khanouche, M.E.; Amirat, Y.; Farah, Z. A parallel approach for user-centered QoS-aware services composition in the Internet of Things. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B. Human-centered artificial intelligence: Three fresh ideas. AIS Trans. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2020, 12, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarosh, S.; Zave, P. Locked or not? Mental models of IoT feature interaction. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 2993–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape-Haugaard, L.B.; Lovis, C.; Cort Madsen, I.; Weber, P.; Hostrup Nielsen, P.; Scott, P. Digital Personalized Health and Medicine. In Proceedings of the MIE 2020, Geneva, Switzerland, 28 April–1 May 2020; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 270, ISBN 978-1-64368-083-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, K.S.; Kenfield, S.A.; Van Blarigan, E.L.; Chan, J.M.; Wiese, J. Ask the Users: A Case Study of Leveraging User-Centered Design for Designing Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs). Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2022, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, A.; Pinsonneault, A. Understanding user responses to information technology: A coping model of user adaptation. MIS Quarterly 2005, 29, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, W.J. Improvising organizational transformation over time: A situated change perspective. Inf. Syst. Res. 1996, 7, 63–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Prinz, A.; Gerdes, M.; Martinez, S.; Pahari, N.; Meena, Y.K. ProHealth eCoach: User-centered design and development of an eCoach app to promote healthy lifestyle with personalized activity recommendations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.W. Designing Pleasurable Products: An Introduction to the New Human Factors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstone, R.; Haddon, L. Design the domestication of information communication technologies: Technical change everyday life. In Communication by Design: The Politics of Information and Communication Technologies; Mansell, R., Silverstone, R., Eds.; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 44–74. ISBN 9780198289418. [Google Scholar]

- Spreicer, W. Tangible interfaces as a chance for higher technology acceptance by the elderly. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies—CompSysTech ’11, Vienna, Austria, 16–17 June 2011; pp. 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Yang, P.; Min, G.; Amft, O.; Dong, F.; Xu, L. Advanced internet of things for personalised healthcare systems: A survey. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2017, 41, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.J.; Fogh, R.; Lund, H.H. Playte, a tangible interface for engaging human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the The 23rd IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Edinburgh, UK, 25–29 August 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: Psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 1995, 7, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghi, M.; Neubert, S.; Geissler, A.; Fleischer, H.; Stoll, N.; Stoll, R.; Thurow, K. A Flexible and pervasive IoT-based healthcare platform for physiological and environmental parameters monitoring. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 5628–5647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xie, L.; Mantysalo, M.; Zhou, X.; Pang, Z.; Xu, L.D.; Kao-Walter, S.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, L.-R. A health-IoT platform based on the integration of intelligent packaging, unobtrusive bio-sensor, and intelligent medicine box. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2014, 10, 2180–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, H.; Schooler, E.M.; Shen, G.; Kamath, S. Remote monitoring and medical devices control in eHealth. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 12th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob), New York, NY, USA, 17–19 October 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, H.-Y.; Wei, C.-W.; Yu, M.-C.; Liang, T.-Y.; Wu, W.-H.; Wu, Y.J. Integrating a mobile health applications for self-management to enhance Telecare system. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozsa, V.; Denisczwicz, M.; Dutra, M.L.; Ghodous, P.; Ferreira da Silva, C.F.; Moayeri, N.; Biennier Figay, N. An Application Domain-Based Taxonomy for IoT Sensors. In Proceedings of the 23rd ISPE International Conference on Transdisciplinary Engineering: Crossing Boundaries, Curitiba, Brazil, 3–7 October 2016; pp. 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayes, A.; Salam, S. (Eds.) The Things in IoT: Sensors Actuators. In Internet of Things from Hype to Reality; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]