Constant Slope Maps and the Vere-Jones Classification

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. : The Class of Countably Piecewise Monotone Markov Maps

- Two elements of have pairwise disjoint interiors, and is at most countable.

- The partition is finite or countably-infinite;

- is monotone for each (classical Markov partition) or piecewise monotone for each ; in the latter case, we will speak of a slack Markov partition.

- For every and every maximal interval of monotonicity of T, if , then .

- T is topologically mixing, i.e., for every open sets , there is an n, such that for all .

- T admits a countably-infinite Markov partition.

- .

- (i)

- For each and , the entry of is finite.

- (ii)

- The entry if and only if there are exactly m subintervals , …, of i with pairwise disjoint interiors, such that , .

3. Conjugacy of a Map from to a Map of Constant Slope

- (i)

- For some , the map T is conjugate via a continuous increasing onto map to some map .

- (ii)

- For some classical Markov partition for T, there is a positive summable λ-solution of Equation (5).

- (iii)

- For every classical Markov partition for T, there is a positive summable λ-solution of Equation (5).

- (iv)

- For every slack Markov partition for T, there is a positive summable λ-solution of Equation (5).

- (v)

- For some slack Markov partition for T, there is a positive summable λ-solution of Equation (5).

4. The Vere-Jones Classification

- irreducible, if for each pair of indices , there exists a positive integer n, such that , and

- aperiodic, if for each index , the value .

- (i)

- Let be a nonnegative irreducible aperiodic matrix indexed by a countable index set . There exists a common value , such that for each :

- (ii)

- For any value and all :

- the series are either all convergent or all divergent;

- as , either all or none of the sequences tend to zero.

4.1. Entropy, Generating Functions and the Vere-Jones Classes

- equals the number of paths of length n connecting i to j.

- The first entrance to j: equals the number of paths of length n connecting i to j, without the appearance of j in between.

- The last exit of i: equals the number of paths of length n connecting i to j, without the appearance of i in between.

- The first entrance to : for a nonempty and , equals the number of paths of length n connecting i to j, without the appearance of any element of in between.

- (i)

- If there is a vertex j, such that then, there exists a strongly-connected subgraph , such that .

- (ii)

- If there is a vertex j, such that , then for all proper strongly-connected subgraphs , one has .

- (iii)

- If there is a vertex j, such that , then for all i.

- I.

- If ,

- II.

- Assume that . Then, by our assumption and Equation (11):

4.1.1. Salama’s Criteria

4.1.2. Further Useful Facts

- (a)

- and M is recurrent or

- (b)

- when either or and M is transient, there is an infinite sequence of indices , such that ():

4.1.3. Useful Matrix Operations in the Vere-Jones Classes

- (i)

- ,

- (ii)

- if for each i, except for a finite set of j values, the matrix N belongs to the same class of the Vere-Jones classification as the matrix M.

- (i)

- Since if and only if , Property (i) follows from Corollary 1.

- (ii)

- By our assumption, for each i, , except for a finite set of j values, so Theorem 6 and Corollary 1 can be applied. Notice that for any nonnegative v,so by Theorem 5, the matrix M is transient, resp. recurrent, if and only if is transient, resp. recurrent. In order to distinguish different recurrent cases, we will use Table 1. Since by (i) , we can write:

5. Entropy and the Vere-Jones Classification in

6. Linearizability

- (i)

- Since T is leo, for a fixed element i of , there is an , such that . Then, by Proposition 3 (ii), for each . This implies that any λ-solution of Equation (5) satisfies:so .

- (ii)

- We assume that T is topologically mixing; see Definition 3. For any fixed element , there is an , such that : since T is topologically mixing, there exist positive integers and , such that for every , resp. for every . This implies that the interval contains whenever ; fix one such n. Then, for any element j of , such that ; hence:for any λ-solution of Equation (5).

6.1. Window Perturbation

6.1.1. Local Window Perturbation

- T equals S on

- there is a nontrivial partition of j, such that and is monotone for each i.

- (i)

- If S is recurrent, then T is strongly recurrent and .

- (ii)

- If S is transient, then T is strongly recurrent for each sufficiently large k.

- (i)

- (ii)

6.1.2. Global Window Perturbation

7. Examples

7.1. Non-Leo Maps in the Vere-Jones Classes

- (a)

- For any choice of ,so that .

- (b)

- If , then and M is transient. There is a summable -solution for M if and only if .

- (c)

- If , then and M is null recurrent. There is a summable -solution for M if and only if .

- (d)

- If , then , and M is strongly recurrent. There is a summable -solution for M if and only if .

- (i)

- The matrix is a transition matrix of a strongly recurrent non-leo map if and only if . The map T is not linearizable for .

- (ii)

- The matrix is a transition matrix of a transient non-leo map . The map T is linearizable if .

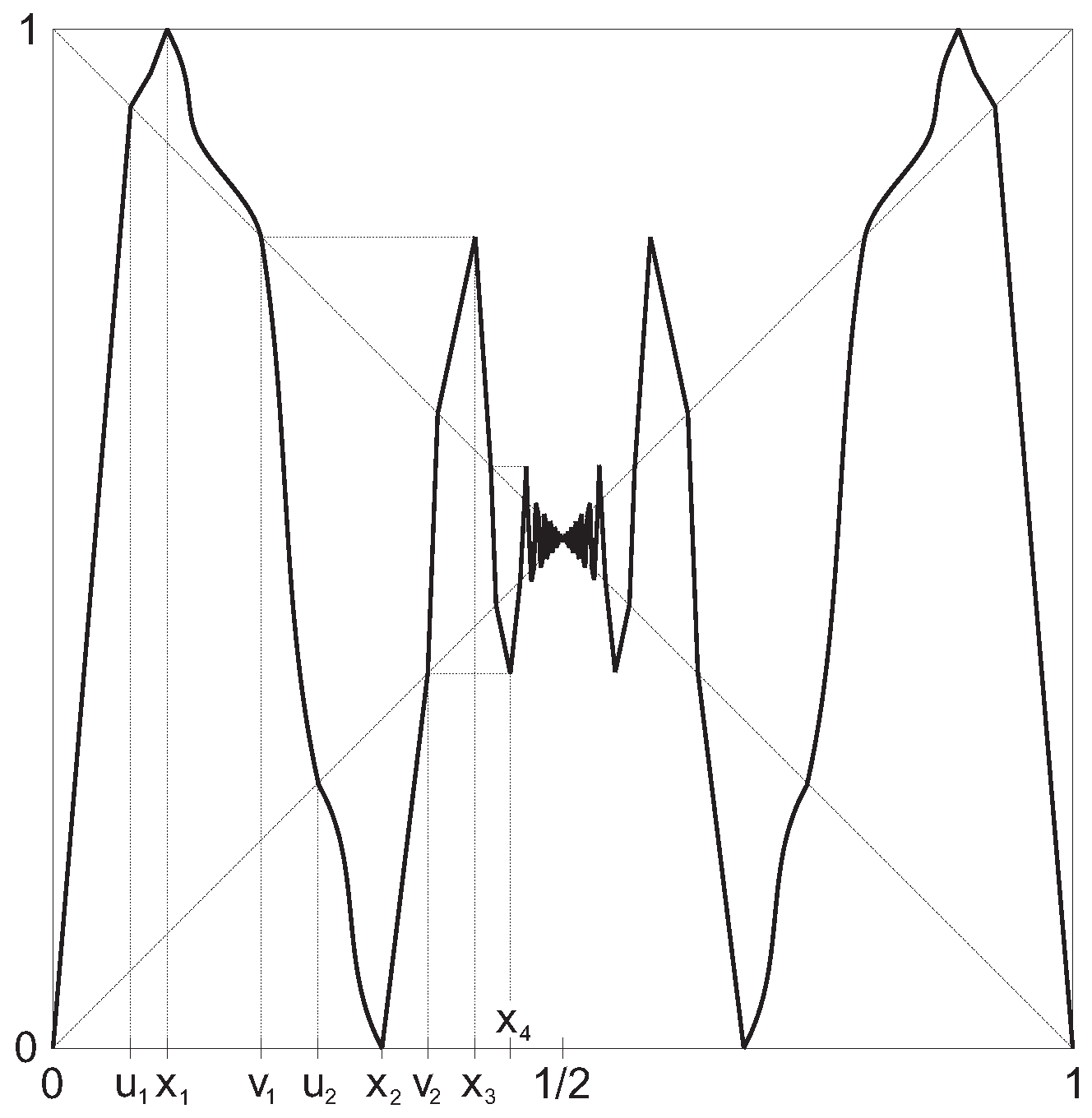

7.2. Leo Maps in the Vere-Jones Classes

7.2.1. Perturbations of the Full Tent Map of the Operator Type

- the window perturbation on is of order (i.e., if we do not perturb S on ).

- Strongly recurrent: First of all, consider the set and the choice:Then, by (48), for and for each , hence:

- Transient: Denoting , let us define:

7.2.2. One More Collection of Perturbations of the Full Tent Map

7.2.3. Transient Non-Operator Example from [23]

7.2.4. Transient Non-Operator Example from [5]

- (a)

- , , , ,

- (b)

- , , ,

- (c)

- for each interval ,

- (d)

- and for each .

- is a conjugacy class of maps in .

- The common topological entropy equals .

- Equation (5) has a positive summable λ-solution for each .

7.3. One Application of Our Results

- (i)

- , Propositions 8 and 13.

- (ii)

- (iii)

- T is not conjugate to a map of constant slope (is not linearizable), Proposition 13.

- (iv)

- T is null recurrent, Proposition 13.

- (v)

- Let be a Markov partition for T; denote the transition matrix of T with respect to representing a bounded linear operator on . Since:we have ; see (i), Section 2 and Proposition 8. Then, by Theorem 11, any recurrent centralized (operator/non-operator) perturbation of T is linearizable. In particular, it is true for any local window perturbation of T on some element of , Proposition 11(i).

- (vi)

- Let be a Markov partition for T, which equals outside of some interval . Let be a local window perturbation of T on some element of ; from the previous Paragraph (v), it follows that is strongly recurrent and linearizable. Consider a centralized (operator/non-operator) perturbation of on some . Then, if is recurrent, it is linearizable by Theorem 10. Otherwise, we can use either Theorem 8 (an operator case) or Theorem 9 (non-operator case; is finite for ) to show that a local window perturbation of of a sufficiently large order is linearizable.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Milnor, J.; Thurston, W. On iterated maps of the interval. In Dynamical Systems, Lecture Notes in Math; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; Volume 1342, pp. 465–563. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, W. Symbolic dynamics and transformations of the unit interval. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1966, 122, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiurewicz, M.; Szlenk, W. Entropy of piecewise monotone mappings. Stud. Math. 1988, 67, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Misiurewicz, M.; Raith, P. Strict inequalities for the entropy of transitive piecewise monotone maps. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2005, 13, 451–468. [Google Scholar]

- Bobok, J.; Soukenka, M. On piecewise affine interval maps with countably many laps. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2011, 31, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katok, A.; Hasselblatt, B. Introduction to the Modern Theory of Dynamical Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Vere-Jones, D. Ergodic properties of non-negative matrices. I. Pac. J. Math. 1967, 22, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruette, S. On the Vere-Jones classification and existence of maximal measures for countable topological Markov chains. Pac. J. Math. 2003, 209, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobok, J. Semiconjugacy to a map of a constant slope. Stud. Math. 2012, 208, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsedá, L.; Llibre, J.; Misiurewicz, M. Combinatorial Dynamics and the Entropy in Dimension One, 2nd ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, Singapore, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Misiurewicz, M.; Roth, S. Constant slope maps on the extended real line. 2016; arXiv:1603.04198. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, P. An Introduction to Ergodic Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gurevič, B.M. Topological entropy for denumerable Markov chains. Soviet Math. Dokl. 1969, 10, 911–915. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, I. Topological entropy and recurrence of countable chains. Pac. J. Math. 1988, 134, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, W.E. Eigenvalues of non-negative matrices. Ann. Math. Stat. 1964, 35, 1797–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.L. Markov Chains with Stationary Transition Probabilities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Misiurewicz, M. Horseshoes for mappings of an interval. Bull. Acad. Pol. Sci. 1979, 27, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Bobok, J. Strictly ergodic patterns and entropy for interval maps. Acta Math. Univ. Comen. 2003, 72, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.E.; Lay, D.C. Introduction to Fuctional Analysis, 2nd ed.; Robert, E., Ed.; Krieger Publishing Company: Malabar, FL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Misiurewicz, M.; Roth, S. No semiconjugacy to a map of constant slope. Ergod. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2016, 36, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, L.; Guckenheimer, J.; Misiurewicz, M.; Young, L.-S. Periodic points and topological entropy of one-dimensional maps. In Global Theory of Dynamical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980; Volume 819, pp. 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brucks, K.; Bruin, H. Topics from One-Dimensional Dynamics (London Mathematical Society Student Texts); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; Volume 62. [Google Scholar]

- Bruin, H.; Todd, M. Transience and thermodynamic formalism for infinitely branched interval maps. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 2012, 86, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Transient | Null Recurrent | Weakly Recurrent | Strongly Recurrent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∞ | ||||

| for all i |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bobok, J.; Bruin, H. Constant Slope Maps and the Vere-Jones Classification. Entropy 2016, 18, 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18060234

Bobok J, Bruin H. Constant Slope Maps and the Vere-Jones Classification. Entropy. 2016; 18(6):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18060234

Chicago/Turabian StyleBobok, Jozef, and Henk Bruin. 2016. "Constant Slope Maps and the Vere-Jones Classification" Entropy 18, no. 6: 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18060234

APA StyleBobok, J., & Bruin, H. (2016). Constant Slope Maps and the Vere-Jones Classification. Entropy, 18(6), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18060234