6.1. Minsky Moment

According to Reference [

44], ‘capitalist economies exhibit inflations and debt deflations which seem to have the potential to spin out of control’. The economies are unstable by nature (this instability, in the most general terms, was mostly related to industrial structure and finance). In this statement Minsky refereed to the Kindleberger’s definition of self-sustaining disequilibrium from the 1970s. The capitalist economy is conditionally coherent. Instead of accepting the state of equilibrium, the focus should rather be on periods of tranquillity, apparent stability, which, in essence, are destabilising.

The neoclassical synthesis tries to explain how a decentralized economy achieves

coherence and

coordination in production and distribution (in other words, how market mechanisms lead to a sustained, stable-price, full-employment equilibrium). In opposition, the Minsky theory focuses on capital development of an economy and

the impact of financial institutions’ activity on production and

distribution. The optimum that is derived from the neoclassical decentralized market processes ‘rules out interpersonal comparisons of well-being and ignores the inequity of the initial distribution of resources and thus of income’. As Minsky stated, ‘inasmuch as our aim is to indicate how we can do better than we have, and as the best is often the enemy of the good, we can forget about the optimum [in neoclassical terms]. Even though a tendency toward coherence exists because of the processes that determine production and consumption in market economics, the processes of a market economy can set off interactions that disrupt coherence’ [

44].

Minsky’s theory can be interpreted in two ways. In Keynesian terms, it should be understood in terms of accumulation of capital in the economy. In Knightian terms, it should rather be interpreted as a problem of allocating resources under risk and uncertainty. The paper refers to the first interpretation. In

Extensions, the second interpretation is referred to. Hence, the role of risk perception and uncertainty in generation and amplification of risk within the system is analysed [

42].

We begin with interpretations of the instability hypothesis in Keynesian terms. Minsky’s theory refers to the general theory of Keynes from the 1930s. Nonetheless, in ‘Stabilizing an unstable economy’, the process of capital accumulation described by Keynes is accompanied by an exchange of current money for the future. At the heart of this theory are not only capital stock and investment but primarily cash flows. Any attempt to model the instability hypothesis must therefore be stock-flow consistent. In reference to the Minsky theory, in the simulation, three types of stylized cash flows are developed: income, balance sheet and portfolio. The income cash flow refers to all payments in the production and sale of inputs and final goods, thus also the one in the supplier searching and purchase modules. The balance sheet cash flow refers to repayment of debts. The third type of cash flow occurs due to transactions in which capital and financial assets are acquired by a new agent. Money in cash form is not analysed explicitly in the model, but the general idea of money and settlements has been taken into account in the model. As Minsky noted, ‘money is created in the process of financing investment and positions in capital assets. An increase in the quantity of money first finances either an increase in the demand for investment output or an increase in the demand for items in the stock of capital or financial assets. As money is created, borrowers from banks enter upon commitments to repay money to the lending banks. In its origins in the banking process, money is part of a network of cash-flow commitments, a network that for the business side of the economy ultimately rests upon the gross profits, appropriately defined, that firms earn’ [

44].

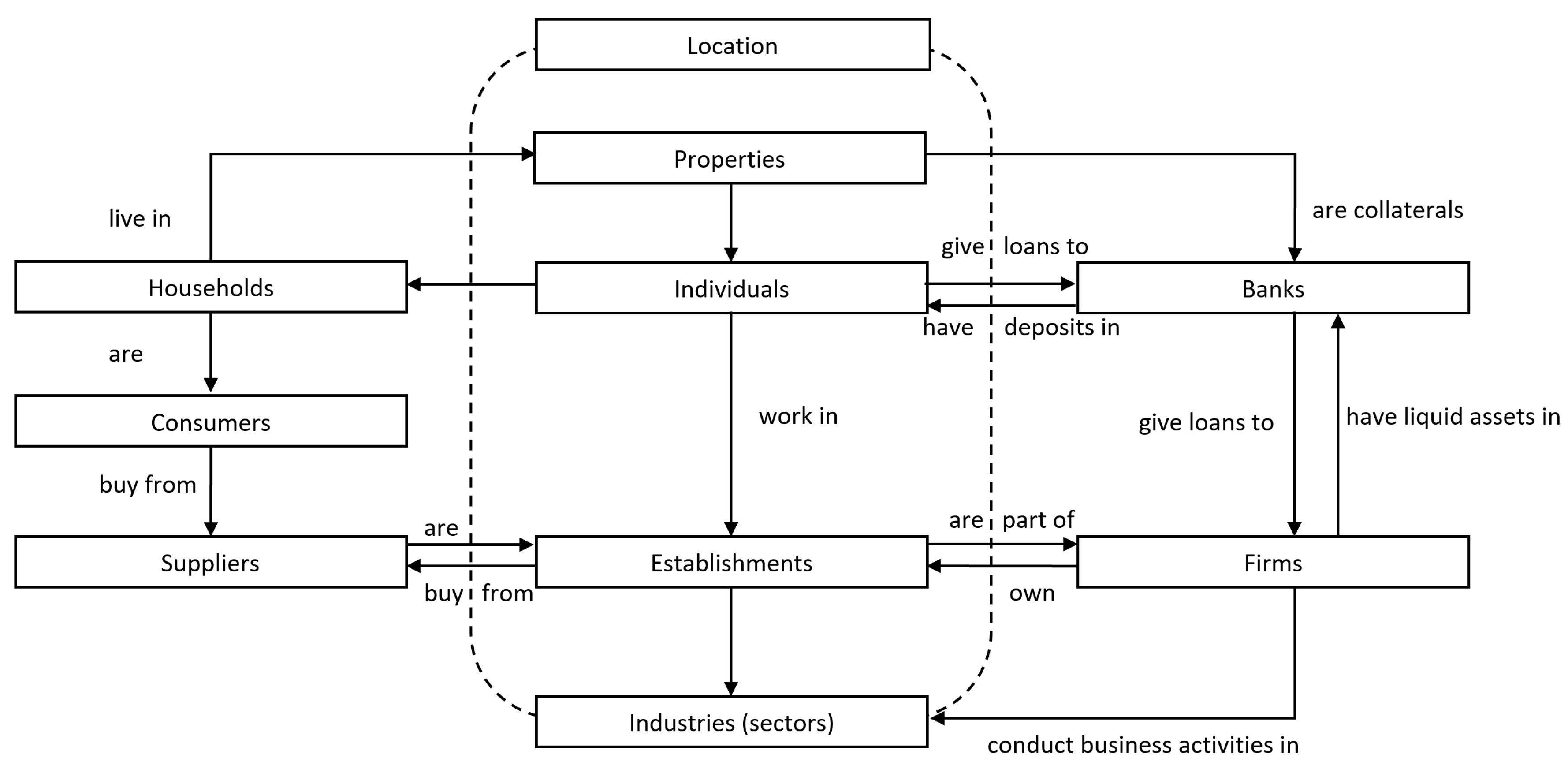

The current money is used to purchase inputs that are used in the production of investment and consumption goods. The purchase of inputs can be funded by the firm from the liquid assets and capital. Otherwise, external funding can be obtained. Financial institutions on the market generate profits from lending funds. ‘The financing terms affect the prices of capital assets, the effective demand for investment, and the supply price of investment outputs’ [

44]. Firms, establishments and individuals are obliged to repay debt, that is, principal and interest rates, within designated deadlines. In Minsky’s basic theory, the focus was on investment. The government budget, the behaviour of consumption and the path of wages were secondary. To make the model more realistic and ensure it can be applied in modern policy making, all the above-mentioned elements were included. Similarly, the flow of money described by Minsky included only loans to firms, while in the simulation, loans to individuals and households were also added. The flow of money in Minsky’s theory, similarly to the simulation, has the following two directions. Individuals make deposits to banks and banks lend money to firms and individuals. In a later period, firms and individuals return funds to banks and banks to depositories.

In this theory the cash flows are influenced by the expected future profits; the flow of money from companies to banks takes place after the realisation of real profits. These expectations need not be always consistent with the final realisation of profits.

Funds can be obtained through negotiation, in which risk perception and uncertainty as well as expectations play an important role. Firms willing to obtain money for carrying out their activity interpret financial results and the economic situation in an enthusiastic way, and in fact often create overly optimistic expectations. While bankers are inherently conservative, though profit-seeking, they are more restrictive in assessing potential gains from a deal. Despite being more restrictive, bankers are also aware that investment in innovation and new products, services and industries is the most profitable. Consequently, their propensity to finance projects from the most dynamic and profitable sectors is usually greater than the projects from other industries, even if the riskiness of the project is higher than average.

Minsky’s theory incorporates elements of Kalecki-Levy theory, according to which the structure of aggregate demand determines profits. The profit expectations depend on the expected level of investment in the future and actual returns on investment. Investments continue on the assumption of both entrepreneurs and bankers that investment will also take place in the future. In order to increase investment, the agents borrow additional funds, frequently assuming unrealistic returns in the future.

According to Minsky, there are three types of agents that are characterised by their relation between income and debt. ‘Hedge financing units are those which can fulfil all of their contractual payment obligations by their cash flows. (...) Speculative finance units need to roll over their liabilities, [that is,] issue new debt to meet commitments on maturing debt. (...) For Ponzi units, the cash flows from operations are not sufficient to fulfil either the repayment of principle or the interest due on outstanding debts by their cash flows from operations. Such units can sell assets or borrow. Borrowing to pay interest or selling assets to pay interest on common stock lowers the equity of a unit, even as it increases liabilities and the prior commitment of future incomes. A unit that Ponzi finances lowers the margin of safety that it offers the holders of its debts’ [

44]. The higher the leverage ratio of firms, the higher the probability of defaulting on debt. Therefore, the reduction of collateral required and credit rating requirements in this scenario leads to an increase in the percentage of speculative and Ponzi agents. Changes in creditworthiness requirements also affect the percentage of hedging, speculative and Ponzi-type agents in the economy. The higher the level of speculators and Ponzi-type agents, the greater the probability of a crisis.

Investment boom increases aggregate demand and spending through a multiplier effect and sales increase. Profits increase with increasing investment, encouraging further investment. In this way, the instability of the system is strengthened until the percentage of speculative investors increases significantly. In the case of prolonged prosperity, assuming that no prudential policies have been applied, the economy becomes unstable, due to the increasing number of speculative and Ponzi-type agents.

Minsky’s instability hypothesis is a study about the extent to which debt affects the behaviour of the system and how the level of debt is considered to be adequate in terms of dynamics of the system. According to this theory, there is no need for external shock for the crisis to occur. The crisis is generated endogenously by agents taking too much risk and by the desire by entrepreneurs and bankers to obtain ever-increasing profits. At the same time, this situation also has consequences for individuals and households. In the event of an increase in insolvencies, banks may default and thus depositors would lose the funds (the case in which by increasing uncertainty individuals decide to withdraw deposits is analysed in

Extensions, see: [

8]). In addition, the situation on the labour market determines changes in the income and wealth of households.

According to Minsky’s theory, increase in investment ‘would never trickle down to the poor and would tend to increase inequality by favouring the workers with the highest skills working in industries with the greatest pricing power’ [

44]. In the simulation, this mechanism was modelled. Firms hire individuals according to their work skills and in industries with the greatest pricing power. Consequently, it leads to inequality. The changes in inequality can be measured using the Gini coefficient as well as other measures of asymmetry and spatial inequalities.

The dynamics of the real estate market is also changing. The increased percentage of job seekers is influencing their shift to cheaper properties and partly ineligible mortgage loan repayment, which again puts banks in a difficult position. Banks are in possession of properties for which there is no demand, and their prices are gradually lowered in order to find a buyer.

Two main components of the theory are the two-price system and the lender’s and borrower’s risk, both derived from theories of Kalecki and Keynes.

The first price system concerns current output prices, that is, costs and mark-ups, that need to be set at a level that will generate profits for the firm from the sale of consumer goods, investment goods, and goods and services purchased by the government in public contracts. If, in the analysis, the external fund increase is also taken into account, the supply price of capital plus the interest rate and lender’s risk must also be considered.

The second pricing system refers to assets. Assets are expected to generate cash flow in the future. These flows are not known and their estimation depends on subjective expectations. How much is able to be paid for such a financial asset depends on the amount of external finance required. The more the borrower becomes indebted, the greater the risk of insolvency; in this sense the price of the asset includes the borrower’s risk. Investments occur when demand price exceeds the supply price of assets. Prices include collateral. After the crisis, usually larger collateral are required, in the expansion period, they are lowered significantly.

As Minsky [

44] states, ‘the costs of financing the production of investment is a cost that enters the supply price of output like the costs of labour and purchased inputs. The fact that a firm has to borrow to pay wages raises the effective costs by the interest payments on the borrowings’. ‘The decision to invest therefore involves a supply function of investment, which depends upon labour costs and short-term interest rates, a demand function for investment, which is derived from the price of capital assets, and the anticipated structure and conditions of financing. Whereas the structure of balance sheets reflects the mix of internal funds (gross retained earnings) and the external funds (bonds and equity issues) actually used, the investment decision is based upon expected flows of internal and external funds’ [

44].

6.2. Simulating an Unstable Economy

In the first scenario, the role and impact of financial institutions on production and distribution of income and wealth in the economy is simulated. As Minsky pointed out, according to neoclassical assumptions, the initial distribution of income and wealth did not matter. Neoclassical models ignore the impact of policies on income and wealth distributions ex post. The inclusion of ex ante heterogeneity was not relevant to the analysis of outcome ex post. In contrast, in the simulated scenario, we show that the processes of a market economy do ‘set off interactions that disrupt coherence’, and that incorporation of heterogeneity ex ante into the model makes it possible to observe changes in distributions ex post, including income and wealth distributions.

In accordance with Minsky’s hypothesis, in the database and model design, the focus was put not solely on heterogeneity in capital stock and on different investment decisions but also on balance sheet changes and cash flows.

In the scenario, firms operate in eight different sectors through establishments. In the first iteration, the most profitable sector is the first sector, thus it attracts the highest percentage of new investors. Other sectors attract a smaller percentage of new businesses. During first iterations we observe fluctuations in the relative profitability of sectors, related to business fluctuations, that is, the effect of the business cycle. In the initial iterations, only stock fluctuations related to intrinsic dynamics of the economy are observed, while in further iterations, it is observed that increased stock fluctuations and a cease in production is experienced by a higher percentage of establishments. The number of firms in each of sectors decreased over a year due to both higher rate of bankruptcies and higher concentration on the market,

see: Figure A6 (on the right) in

Appendix D. At

there are 18727 establishments in the database. At

, 14112 establishments from the database at

continue operating on the market. 4615 establishments ceased to produce, while 9887 new establishments were attracted by the market due to higher relative profitability of selected sectors. At

, 15727 establishments from

operate on the market, while 2773 new establishments are created. In total, 18500 establishments are in operation. At

, 15357 establishments from

operate on the market but only 1546 new establishments are established due to deterioration of market conditions. In total, a lower number of establishments (16,903) with respect to

operate on the market. Some firms go bankrupt, while others cease their activity in selected establishments that are operating in less profitable sectors. At

, 15,357 establishments stay on the market and 1491 new establishments are created. In total, 16848 establishments continue operation.

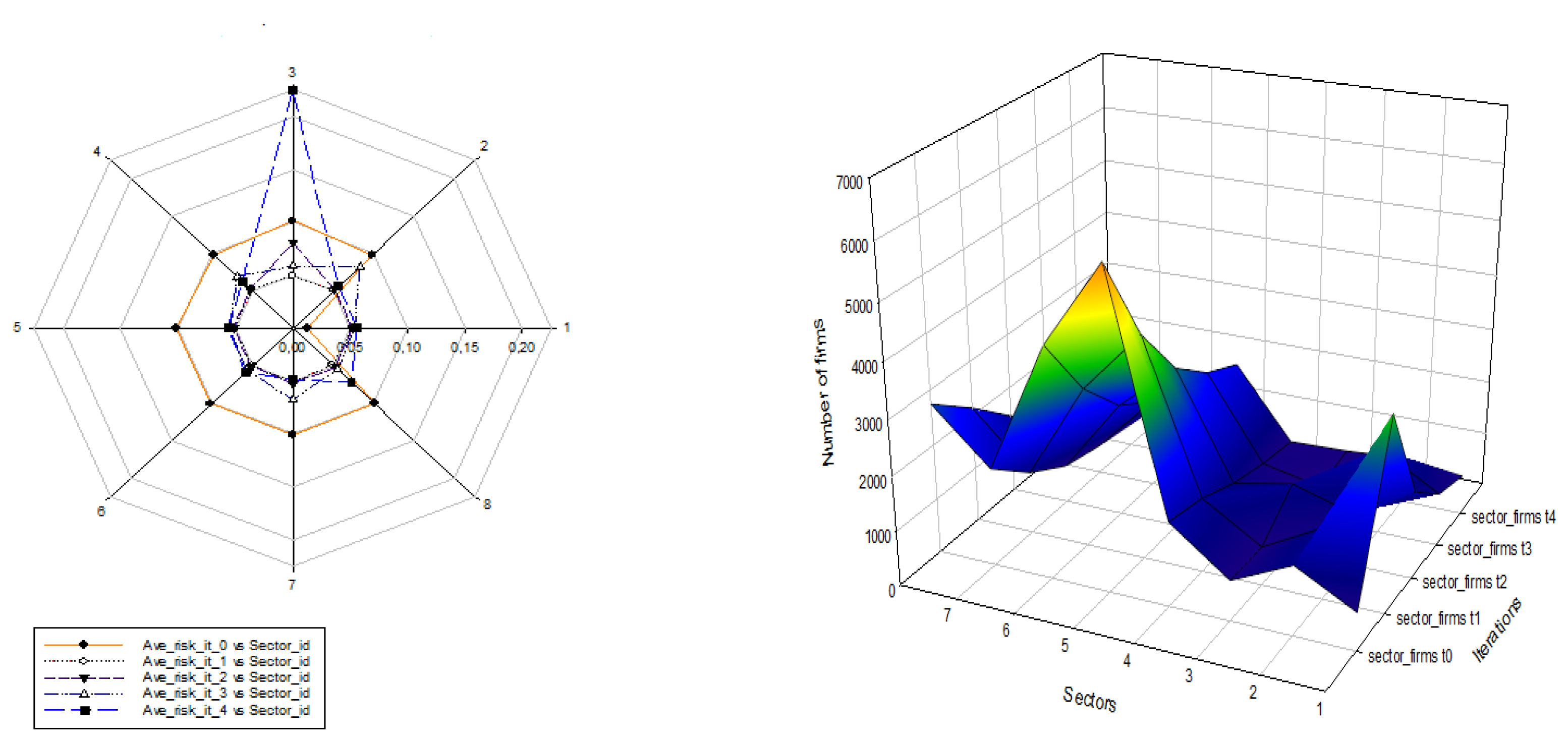

In next iterations, there are higher levels of debt and leverage and increased financial risk in the sectors that were the most profitable in the previous periods. The risk spreading between sectors was visualised in

Figure A5 (on the left and on the right side) and

Figure A6 (on the left). Over a year, the higher number of firms’ bankruptcy with respect to the previous periods was observed, indicating the gradual

endogenous generation of the crisis. Occasionally, though gradually more frequently, firms had problems finding a supplier, which is related to the cessation of business activity by selected establishments, and thus the interruption of network of transactions established between establishments and suppliers. The data could be analysed for further iterations than four (one year) but the goal was to show that a crisis can emerge endogenously in a relatively short period of time, such as 1–4 quarters, as it was the case during the financial crisis (Q2 2008–Q2 2009).

The problem of searching and matching the suppliers in the supply chain module gains importance. The time required to searching for supplier is increased due to the fact that new transaction relations are established with suppliers in further territorial units than previously.

When the uncertainty on the market increases and indicators of profitability and riskiness deteriorate, a lower percentage of firms is eligible for a loan. Establishments lose creditworthiness and are forced to restrict production, which in turn worsens economic conditions. At , of establishments were checked for creditworthiness in the module Consumer credit admissibility 1, while in Consumer credit admissibility 2. In the following iterations, these values were respectively: and at , and at , and and at . The firms and establishments’ conditions are also closely related to the problems of specific industries and fluctuations in the economy.

Expectations of lower profits lead to a reduction in the flow of money from companies to banks and from banks to companies, worsening the state of the economy. Banks are on the one hand aware of the higher risk related to granting loans to companies that qualify for the liquidity problem procedure, on the other hand it allows them to earn a premium. Overall, however, they provide loans for shorter periods, which is related to the general uncertainty in the market.

In the simulation cycle under first scenario, the number of companies with higher debt and higher leverage gradually increases. Using the simulation, changes can be observed in the distribution of the firms’ debt and leverage, rather than just analysing growth of the overall average debt and leverage. However, as the crisis becomes more severe, more firms with excessive debt and leverage go bankrupt or cease their activities in selected establishments; see:

Table A11 in

Appendix D.

The initial boom also encourages households to increase consumption, which in turn increases their overall debt, also affecting the value of debt service to income (DSTI), debt to income (DTI), debt to assets (DTA) and loan to value (LTV) ratios, see:

Figure A12,

Figure A13,

Figure A14,

Figure A15 and

Figure A16. After the first iteration, the percentages of households that have DSTI ≥ 30% equal to 4.7%, and DSTI ≥ 40% equal to 2.7%, while the percentage of households with DTI ≥ 3 equal to 3% and DTI ≥ 4.5 equal to 1.3%. After the second iteration, the percentage of households with DSTI ≥ 30% was equal to 3.6%, and DSTI ≥ 40% equal to 2.2%, while the percentage of households with DTI ≥ 3 equal to 2.1% and with DTI ≥ 4.5 equal to 0.9%. After the third iteration, the percentage of households with DSTI ≥ 30% is equal to 4.6%, and with DSTI 40% ≥ 3.2%, while those with DTI ≥ 3 is equal to 1.9% and with DTI ≥ 4.5 equal to 0.9%. After one year, the percentage of households with DSTI ≥ 30% was equal to 5.04%, and with DSTI ≥ 40% was equal to 3.5%, while with DTI ≥ 3 this percentage was equal to 2.2% and with DTI ≥ 4.5 the percentage was equal to 1.1%. The percentage of households with respective values of DSTI and DTI at

are lower than at

. There are two reasons that explain this pattern. Firstly, households with very excessive debt default are removed by the system. Secondly, highly indebted households will not apply for any new loans and they pay back part of the debt. Nonetheless, as soon as their creditworthiness improves due to loan repayment, they are attracted by the market via mechanisms described by Minsky and the ratios start to deteriorate. Changes in investment and external financing directly affect the market imbalances. Individuals with lower qualifications and level of education experience a gradually deteriorating situation on average.

After a year the Gini coefficient for income distribution is equal to 39.9% and for wealth distribution is 60.8%. After two years, the values are 41.1% and 61.3%, respectively. The LAC is equal to 0.96901 and 0.93896 after four quarters. The point for income, while it is equal the case of wealth. The adjusted azimuthal asymmetry (AAA) is equal to for income and for wealth.

Due to endogenous changes in the decisions of agents and their interactions, the dynamics of the markets and economy also changes. In particular, the dynamics of the labour and real estate markets change. Higher mortgages and a difficult situation on the labour market affect the dynamics of the real estate market. More properties are marked for sale and their price is reduced accordingly. On average, the prices of properties decreased by 2% in one year. It is possible to analyse a decrease in prices in each spatial unit, for example, region, however the results are not reported for confidentiality reasons.

With the deterioration of a favourable economic situation, the number of insolvencies and the NPLs ratios of banks increased; see:

Appendix D (

Figure A7 (on the right) and

Figure A9 and

Figure A10 (on the left and right). Higher non-performing loans affect the supply of credit in subsequent iterations. In the model it is possible to use two methods of determining the supply. If the first one is used, banks adopt similar strategies in groups. If the second is used, there may be a greater degree in the heterogeneity of strategies. In both cases, these patterns were observed. The model allows the analysis of differences in non-performing loans according to the loan type which thus reflects another aspect of heterogeneity. Using simulation, we can also analyse the changes in profits (

Figure A8 (on the left)), equity (

Figure A8 (on the right)) or the fulfilment with the capital and liquidity requirements which were set on too low levels (

Figure A11 (on the left) and

Figure A11 (on the right)).

Stabilizing Unstable Economy via Macroprudential Tools

In the second scenario, the behaviour of the economy is simulated, assuming the implementation of macroprudential policy aimed at stabilising the unstable economy. All banks set the capital requirements set by the regulator as well as apply the recommendations with respect to debt to income (DTI), debt service to income (DSTI), debt to assets (DTA), loan to value (LTV) ratios and leverage ratio (LR). In the economy, the activity of companies is conducted in the eight sectors grouping NACE industries. Among the analysed sectors, the most attractive for potential entities is the third sector, while the relatively least profitable for investors is the eight sector. In the case of any industry, there is no significant decrease in relative profitability. In first scenario, it was observed that the role of some of the sectors, that is, real estate sector, increased sharply, and then was significantly reduced. In the second scenario, no sudden discontinuity of production or increasing number of bankruptcies were observed. There are were no significant changes in product prices.

The expectations are relatively much more consistent in time than in the case of the first scenario. In this scenario, these expectations are only slightly different than those formed in the previous period and adapt to the fluctuations of the economy. Stock fluctuations are consistent with the dynamics of the economy. There is no stock accumulation or stop to production and sales of stored goods. In this scenario, the leverage level is moderate. Only in the case of a small percentage of establishments was production stopped completely.

In this scenario there are no searching-matching problems between the establishments in the search for suppliers. Quality-to-price ratio of establishment in relation to quality-to-price ratio in a given sector is the appropriate determinant of the supplier’s search decision. In most cases, it is possible to find a supplier in a given spatial unit that has a sufficient quantity of produced and stored goods. The search for a supplier in the unit that exceeded the basic spatial unit is moderate and corresponds to normal time market dynamics. The additional costs generated by transportation of inputs for establishments’ production of goods were also moderate.

Most firms have adequate liquid assets and adequate creditworthiness. Additional funds will be used for further investment. A very low percentage of establishments were eligible for the creditworthiness check in connection with transitional liquidity problems. Transient problems of establishments on the market are related to temporary economic fluctuations in industries, as well as market dynamics. In this scenario, banks have adopted similar credit requirements for less risk-prone companies. However, banks differ in credit requirements for more risk-prone businesses, especially firms with temporary liquidity or financial problems. The tightening of the criteria has countered the financial crisis. Of particular importance was the observation of return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), financial risk and credit history of companies.

In the case of a low number of establishments, a readjustment of quantity was required, and the final purchase of the inputs was lower than the intended one. Banks providing loans for the purchase of inputs were characterised by different risk aversion and strategies on the market. In some cases, the network effects have been maintained. The establishments applied for a loan in a matched bank, thus maintaining a transaction link (edges in the network). For other transactions, there was a change of the loan-granting bank. When searching for a bank that will grant short-term credit for the purchase of inputs, the companies were mainly driven by the interest rate and the supply of credit.

In the model it is possible to use two methods of determining the supply. If the first one is used, banks adopt similar strategies in groups. If the second one is used, a greater degree of heterogeneity of strategies is observed. In the first case, network effects associated with transaction relationships in the market have been maintained. Individuals choose banks to apply for a loan according to the interest rates on consumer loans offered by banks. Granting a loan also depended on credit supply and sectoral exposure requirements. Some banks have exhausted the supply of consumer loans, which means that according to the strategy defined for a given period, the funds were spent on other activities such as granting short-term and long-term (investment) loans to companies, and residential and non-residential loans to individuals.

Within the second method, during the year the same number of individuals applied for a loan at the matched banks; a very high percentage of these applications were successful. In this case, network effects associated with transaction relationships in the market were maintained. The supply of consumer loans and sectoral requirements limited the number of loans granted.

In both cases there were also no searching-matching problems between consumers and suppliers of goods. Also, the quality-to-price ratio in relation to quality-to-price ratio in a given sector is the appropriate determinant of the supplier’s search decision. In most cases, it has been possible to find a supplier in a given spatial unit that had a sufficient quantity of produced and stored goods. In some cases, the search for suppliers exceeded the basic spatial unit, generating a modest cost of goods transportation. It did not generate an excessive burden on households.

Demand of establishments and households was complemented by demand from the government, through public procurement. The establishments that signed the public contracts produce high-quality products. These establishments were also part of the largest companies on the market.

In the case of households within ‘Housing stress!’, the cost of accommodation, whether in the case of servicing a housing loan or renting, proved to be excessive. These households changed their residence to a cheaper property. The dynamics of the housing market was not excessive and was consistent with household income fluctuations. In the case of a very low percentage of households, their insolvency was observed, as was an increase of NPLs in the banks by the value of their loans. The prices of properties fluctuate on the market as a whole but the prices remain relatively stable within a determined region.

Using the simulation, it is also possible to compute which percentage of households purchased a new property in cash and which have applied for a residential or non-residential loan. Demographic trends were fully preserved in the scenario. The probability of survival or death has been specified according to Central Statistical Office data. As a consequence of the death of individuals, inheritors gained additional deposits. Most companies were taken over by the heirs, while in cases of negligible value the inheritance was rejected. In some cases, the deceased was the owner of the property charged with the loan. These properties were taken over by the bank and were resold at a lower value. In the case of survivors, the tendencies of completed education by individuals were also maintained.

Some companies were not created despite starting the company opening process. Some did not obtain a business license, and in some cases, funds were not sufficient to run a business. Credit applications are a special case in which the entrepreneurs compared the interest charged by the banks. The banks also checked whether the supply side restriction was fulfilled and whether the sectoral exposure did not exceed the requirements. Sectoral exposures have made it possible to limit potentially excessive credit growth in the most profitable sectors at any given moment, including in the real estate sector, which normally expands dynamically during prosperity. The larger companies were funded with contributions from entrepreneurs. There was an increase in average goodwill points during an expansive phase of a business cycle. At the same time, the structure on the market changed, with some activities ceasing and other new activities being created. New establishments were mostly opened in sectors with high or moderate risk. Changes in the number and structure of firms on the market corresponded to the usual dynamics of the economy. There was no increased concentration of capital, business clustering, excessive bankruptcies or escalation of reductions of labour force in already operating establishments.

An analysis of the distributions describing the attributes of firms and establishments does not allow the identification of situations typical of financial or economic crises and symptoms of overheating of the economy. In this scenario, a significant increase in the risk of activity of firms and establishments on the market was not observed, nor was the strong growth of the economy and the increased financial risk of a particular industry. The average risk to the business activity in the market was moderate.

The lack of concentration of financial risk in a given industry is largely due to the introduction of regulations for maximum exposure to a given industry. The situation of banks is stable. For the first and the second procedure of supply determination, the NPL ratios were moderate. Liquidity requirements are met in the case of most banks. Capital requirements were fulfilled at the level of 8%, introduced by bank regulator. None of the banks declared insolvency. A very low percentage of individuals declared insolvency as a result of net savings at a negative level. The NPL ratios and the growth (inflow) of NPLs of banks was modest.

The stabilising effects of macroprudential policies for the economy and the financial system is significant, however the effect on reducing inequality is ambiguous. The richest agents on the market seem to remain unaffected by the introduction of the policies. In extreme cases, the rich get richer. After one year, the Gini coefficient for income distributions was equal to 39.7% and 60.6% for wealth. After two years, the values were 40.1% and 60.9%, respectively. The Lorenz Asymmetry Coefficient (LAC) was equal to 0.97672 and 94782 respectively. The point for income, while it is equal for wealth. The adjusted azimuthal asymmetry (AAA) is equal to in the case of income and in the case of wealth. The results do not differ significantly in the next four iterations.