(Neg)Entropic Scenarios Affecting the Wicked Design Spaces of Knowledge Management Systems

Abstract

1. Entropy, Syntropy, and Negentropy in Recent Knowledge Creation and Management Contexts

2. Entropic Potentials in the Context of Personal and Institutional Absorptive Capacities

- Internal AC meta-routines for managing variation, selecting, sharing, reflecting, updating, and replicating as well as some form of comparison to the external environment for managing adaptive tension (e.g., reference groups, benchmarking).

- External AC meta-routines for identifying, recognizing, and learning from valuable externally generated knowledge in collaboration with stakeholders, as well as transferring external knowledge back by linking it to in-house capabilities.

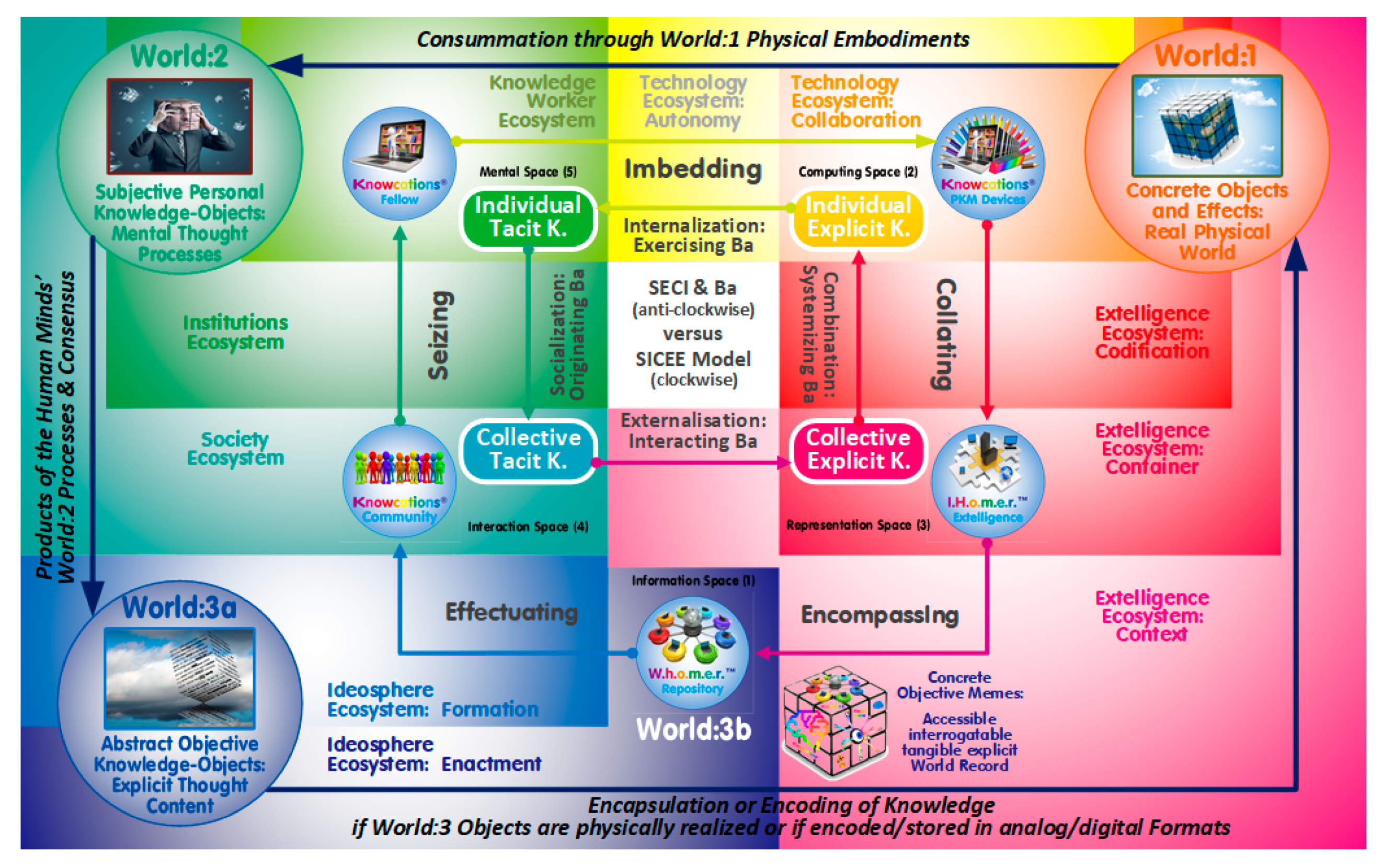

3. Popper’s Three World Perspective and Its Role in a Novel PKMS Conceptualization

4. Outdated Book-Age Diffusion Paradigm as a Cause of Escalating Entropies

- An individual knowledge worker applies learnt knowledge to his/her own ideas (to be referred to in the following as memes) to crystallizes and explicates them over time (in acts of cumulative synthesis [31]) which occupies a kind of personal world:3a ‘pigeon hole’ containing an up-to-date aggregated variety of his/her abstract, non-linear, partially connected, meme explications.

- This ‘pigeon hole’ is only accessible and interrogatable via the individual’s own memories and/or knowledge cues (defined as “external reminders about previously experienced internal knowledge” which may be “any kind of symbol, pattern or artefact, created with the intent to be used by its creator, to re-evoke a previously experienced mental state, when used” [32] (pp. 3, 21)).

- Whenever an already explicated and accessible meme from the ‘pigeon hole’s’ historic content is paraphrased, re-versioned, or annotated (or an original meme is recorded), novel world:3 content is created. If others’ explicit world:1 memes are directly or indirectly quoted, scholarly practice requires citing the original source by referencing their world:2 authoring or editing minds and physical world:1 container (e.g., document, file, web page).

- This personal world:3 ‘pigeon hole’ contains the objective linguistically formulated thought content in the form of abstract explicit knowledge objects and represents—in terms of this argument—the individual’s holistic ‘big-TK’ (theory/knowledge). As a non-physical imaginary virtual construct, it is neither accessible nor interrogatable by others. Accordingly, it may only be effectively disseminated via resourcefully combined subsets of ‘small-TKs’ in a variety of world:1 physical/digital artefacts and knowledge assets (defined as “nonphysical claims to future value or benefits” [33] (p. 335)) as, for example, research papers, conference presentations, chapters, reports, or prototypes.

- The world:3a-to-1-transitional ‘small-TK’ instantiations are, however, susceptible to gaps, disconnects, overlaps, and sporadic modifications “due to, for example, page restrictions, diverse target audiences, confidentiality considerations, project progress updates, error retractions, sponsoring agreements, and partial or extended re-publications“ as well as reviewers’ demands, editing or curating interventions, datedness, erroneous quoting or citing, incorrect copies, and falsifications [30].

- The over-simplistic copy-and-paste digital document creation alluded to contributes progressively to the share of information entropy to be perceived as overload. As discoverable entropic public knowledge, it is threatening the finite attention and carrying capacities referred to in the introduction. This unsustainable situation is aggravated by the lack of personal tools and mentoring which also inhibits the mobility, portability, and shareability of individuals’ expertise, capacities, and capitals.

- Adding to the woes of discoverable knowledge constraints are current online and publishing realities which inhibit engagement in a wider sharing, faster diffusion, and more rapid iterative improvement of ideas, sources, data, work-in-progress, preprints, and/or code and, consequently, are stifling innovation as well as academic reference/reputation systems [34].

- The non-redundant explicated world:3 knowledge also expands with academic and technological advances but is, at the same time, weakened by proliferating and growing “structural holes” [35], referring to the potentially beneficial but unrecorded ties between knowledge clusters ranging from memes, over to approaches, to specializations and disciplines (the theories of organizational learning and knowledge creation, for example, “have been pursued as independent themes for almost two decades” [36] (p. 113). The lack of connectivity contributes to undiscoverable public knowledge (islands and silos) and inhibits methodological approaches to better tackle complex transdisciplinary ‘wicked’ problem spaces.

- A further weakness is today’s ineffective utilization of the explicit accumulated world record supported by top-down KM traditions. Stewart and Cohen [37] coined the term ‘extelligence’ to position it as the externally stored counterpart to the intelligence of the human brain/mind tasked with understanding; together they are driving each other in a complicit process of accelerating interactive co-evolution.

- Due to the deficient awareness (and respective educational interventions) regarding the status quo, personbytes and firmbytes are severely constrained as extelligence only generates competitive advantage if it is accessible and augmentable by individuals who know how [37]. As a result, societies are facing widening innovation and opportunity divides.

- Current reviewing and publishing practices also prevent the sharing of “magnitudes of invisible work” (defined as the “gap between formal representations, including publications, and unreported ‘back stage’ work” [38] (pp. 606–607) termed by Bush [22] as the “scaffolding” of research output. As undiscoverable private content knowledge, others are forced to re-spend the energy and to start over.

- Moreover, today’s digital authoring still compels us to provide linear accounts (digital documents following the outdated book-age paradigm) of nonlinear realities (Popperian world:3 as well as real world) preventing the effective sharing of knowledge already understood in holistic transdisciplinary ways. As undiscoverable private non-linear relational knowledge, this cause prevents benefitting from knowable and sharable nonlinear content and contexts.

- Non-standardized incompatible formats continue to underpin fragmented records of the human intellectual heritage instead of unlocking access as well as collaboration capabilities by instantiating a world:3a-like tangible interrogatable generative heritage repository based on non-redundant and associatively indexed content.

5. Shifting Paradigm from Document-Centricity to a Tangible Memetic Popperian Third World

6. Utilizing the Memes’ Higher Granularity for Re-Inventing the Knowledge-Creating Model

6.1. The Framework of the Ten Digital Ecosystems

6.2. The SECI Versus the SICEE Cycle Versus the Sensemaking Loop Model for Intelligence Analysis

6.2.1. The Foraging Loop

- External data sources [Knowledge K0] are identified, verified, contacted, and evaluated [Action A0] according to (initial or subsequently adapted) information needs [Task T2] and interrogated during field and desk research. The data collected is filtered for relevance [A1] and temporarily stored in a physical ‘shoebox’ or digital case file [K3].

- The case file [K3] is accessed for further screening, reading, sorting, and extraction [A4]. Experiences gained allow for re-assessing and revising related sources and content [T5], for adjusting evidence [K6], or to support additional evidence requirements [T8] in order to continually improve the value of information subsets passed on from the shoebox [K3] to the evidence or memes file [K6] (Knowledge Worker Ecosystem).

- What may be captured during project work in the individual’s PKMS repository depends on the evidence gathered [K6], on the schematizing to be covered (e.g., classifying, contextualizing, interpreting, annotating, summarizing, or formatting) [A7], and on the further needs established [T8] (Imbedding Space based on Autonomous Technology Ecosystem).

6.2.2. The Sensemaking Loop

- Captured content is stored in the topics/schema or memeplexes file [K9] and may be linked on an on-going basis to the established/emerging schemas [A7] which allow analysts to structure the content for later synthesis and communication (Collaborative Technology Ecosystem).

- Once sufficient content is available, the analyst/author may start building his/her case [A10] which may need some support [T11] but, if finalized after some potential re-evaluation [T14], results in, for example, scripts, hypotheses, conclusions, or new meanings [K12] (Collating Space within Extelligence Codification Ecosystem).

- The different content sections may be cumulatively synthesized to tell the story as knowledge or learning assets [A13] and, after further re-evaluations [A14), are to be shared, presented, or published via different media [K15] (Extelligence Container Ecosystem).

- Utilizing a PKMS requires a further decision on what part of any newly created or prior confidential personal work to voluntarily share with the PKMS community. The memes chosen may significantly outstrip any document shared or published traditionally. Due to the links and associated knowledge objects, the PKMS community may receive an information-richer content with the negentropic potential to limit invisible work and structural holes and to afford better online diffusion options and non-linear publishing (Table 1) (encompassing space within extelligence context ecosystem). Confidential meme categories further allow monitoring projects-in-progress [T2,5,8,11,14] which contain: Forethoughts focusing on longer-term objectives, plans, and related responses; Intentions focusing on shorter-term tasks and diaries, and Evaluations focusing on feedbacks and personal assets and reflections.

6.2.3. The Popperian World:3b Creating and Curating Process

- Together with any global content updates contributed by the PKMS own or partner services, the updates are aggregated and immersed within the cumulatively synthesized historic knowledge base, termed World Heritage of MEmes Repository (WHOMER). Although its structure resembles a complex entity-relationship-model, any meme or connection also just represents a distinctly structured generic record which can be intercompared by the centralized services to allow for vetting to identify any duplicates.

- In such a case, identical memes from different sources are merged while their relationships with diverse meme sets and usage histories are fused to preserve all information. A reference record of every meme shared is also kept, even if it might be blocked from dissemination due to, for example, legal, ethical, or falsification reasons. Any identical meme uploaded in the future is, hence, identifiable to trigger appropriate actions.

- The consolidation and curation of this interrelated, associatively indexed, multi-disciplinary content is envisaged to steadily mature—with a growing community and meme base—into a single unified digital knowledge repository representing the tangible interrogatable equivalent (world:3b) of the philosophical notion of Popper’s abstract intangible inaccessible third world:3a.

- All the interventions alluded to, so far, aim for the associative integrity of the WHOMER knowledge base (analogous to the relational integrity of relational databases). Once this state is secured, the updated repository can be made accessible to the PKMS community.

6.2.4. Feeding Back the World:3b Updates to the Decentralized Devices of the PKMS Community

7. The Negentropic Consequences of the Value-Adding World:3b Services

- Metrics: While reputational metrics in social network communities are based on simple clicks, likes, reads, downloads, or responses, academic scholars are accustomed to a sophisticated research and reputation economy where original discoverers/authors are credited based on the evidence provided by citations and references which—weighted by their publisher’s status—contribute to citation indices and impact factors [34]. The underlying methods, however, are “generations old and by now are totally inadequate for their purpose” [22]. Seventy-five years after Bush’s critique, they are still following the book-age paradigm centered on the stable context of far too large paper-or-pdf-based granularities, unable to adequately respond to today’s volatile digital content scenarios by affording effective incentives for wider and faster diffusion and for more rapid iterative improvement. By advancing negentropy, granularity, generativity, and traceability, WHOMER’s metrics afford vital differences.

- Reporting Services: Being at the forefront of transdisciplinary idea generation and innovation, knowledge generation and diffusion can be further enhanced by unearthing promising leads and emerging trends way before link-based search algorithms are able to channel the attention of knowledge workers and entrepreneurs towards exciting new developments.

- Boundary Object Affordances: By bridging disciplinary divides or by aiding transitions from ill-to-well-structured representations (e.g., standards or infrastructure), boundary objects (BO) offer a shared collaborative space of common understanding to afford diverse social actors interpretative and tailorable flexibility to local and disciplinary contexts [38]. The PKMS affordances predestine its application for creating and using BO-artefacts as well as experience management. While the latter relies on “methods and technologies that are suitable for collecting experiences from various sources (documents, data, experts, etc.)”, the former requires identifying and decontextualizing reusable parts of successful practices and solution to favor defined generic viable approaches fitting wider classes of tasks and problem spaces [44]. Such artefacts (e.g heuristics, frameworks, or templates) can be easily shared by the PKMS community members or expertly developed by WHOMER professionals.

- The PKMS Educational Learning Assets Agenda for Personal Learning Environments (PLEs): Irrespective of the remedies put forward in this article, Digital Personal Learning conceptualizations are gaining momentum aiming for designing motivational content and enabling interventions and for the further and faster (self-)development of learners’ potentials [45,46]. As an example of digital platform ecosystems (DPE), collaborating learning management systems (LMS) and knowledge management systems (KMS) are meant, in this respect, to accommodate social actors with highly diverse ambitions and skills as well as expectations to gainfully utilize the DPEs’ resources and generative potential in their personal and local contexts [47]. With the PKMS logic and logistics employed to create LMS-compatible memetic e-learning assets, the learner may also be supplied with their respective PKMS memes for easing retention, referencing, repurposing, and further studying utilizing complementing WHOMER traceabilities. Further value is anticipated in respect to afford the non-linear LMS learning opportunities [48].

- Notifying Services: Having reflected on the merits of attention-guiding/saving reporting to circles of people above, affording the same purposefulness to individualized spaces seems a logical next step. It may, hence, be prudent—within a meme’s genealogical tree or relational network—to notify their linked meme siblings and, by extension, those who employed them about certain state changes of their parent memes (e.g., update or expiry notifications, endorsements, retractions, withdrawals, or falsifications). First-time interests in memes may include informing potential users by simple markers or icons. Once memes have been utilized or cited, authors seldom undertake any post-monitoring or follow-ups which may deprive them from revising or advancing their work; being made explicitly aware of these opportunities can provide a welcome added value.

- Institutional KMS Co-evolutions: LMS and Notifying (personal) versus Metrics and Reporting (public) are services positioned on the opposite ends of a cooperative continuum which also are mirrored in the world:1 technology ecosystem (autonomy versus collaboration) as well as world:2 knowledge worker and society ecosystems. This continuum represents a myriad of externally clustered subsets as well as potential agglomerations where world:2 professionals and their stakeholders may form institutions and where organizational intelligence and memories may need to be captured, synthesized, and protected and the demand for further types of prospective Institutional WHOMER (or I-HOMER) services may originate.

8. Discussion: From Entropic to Negentropic States

- Current digital technologies are facilitating highly granular networks of instantly, continuously, and ubiquitously connected agents empowered to collaboratively create and directly share information without the need of market intermediaries [51]. They are constrained not only by humans’ finite attention capabilities but also diverse concerns (e.g., confidentiality, copyrights, commercial interests, and market dominance strategies based on service barriers, captured audiences, walled garden approaches) and deficiencies (e.g., incompatibilities, lack of tools and functionalities).

- Flexible labour amounts (rather than discrete units of uniform personbytes) are defining shifting demand patterns altering the granularity of labour markets with transferring the control over when, where, how, and with whom to offer one’s time and competencies to the individual supplier [51], accompanied by rising competitive pressures, further evolving domain-specific knowledge and specializations as well as growing needs for flexible skill sets and self-development [52].

- Current network economies are differentiating between content creation, delivery, and distribution services. The unbundling of the messages from the medium and their re-bundling are propagating snowballing information granularities and entropies of off-the-rack, on-demand, and/or tailor-made output configurations with further content and feedback constantly devised by social media users as well as by platform algorithms based on individuals’ social media preferences [51].

- While social media platforms provide granular forms of voluntary connectivity between personbytes by creating social capital as a kind of digital word-of-mouth communication in neighborhoods and communities, institutional granularity embodies essential firmbyte structures for managing and disintermediating supply, production, and distribution processes across complex value chains as a means for the combinatorial innovation and competitiveness of organizational capital [51]. SECI and Ba concepts [25] explicitly urge leaders to nurture individual autonomy, knowledge-related personal proficiencies/assets, and creative interactions for converting ‘nano’ and personbyte into firmbyte and networkbyte performances. Traditional centralized top-down approaches, nevertheless, still neglect synergies to collectively benefit from (personal and organizational) prior accumulated knowledge subsets, absorptive capacities, ambidextrous and dynamic capabilities at the expense of disinterested employees and failed KMS approaches.

9. Conclusions and the Road Ahead

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bratianu, C.; Andriessen, D. Knowledge as Energy: A Metaphorical Analysis. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Knowledge Management, Southampton Solent University, Southampton, UK, 4–5 September 2008; pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World. In Computers, Communications, and the Public Interest; Johns Hopkins Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, U. Knowledge Management Decentralization as a Disruptive Innovation and General-Purpose-Technology. In Proceedings of the 20th European Conference on Knowledge Management, Lisbon, Portugal, 5–6 September 2019; Volume 2, pp. 923–932. [Google Scholar]

- Melinat, P.; Kreuzkam, T.; Stamer, D. Information Overload: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Informatics Research, Lund, Sweden, 22–24 September 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- Roetzel, P.G. Information Overload in the Information Age: A Review of the Literature from Business Administration, Business Psychology, and Related Disciplines with a Bibliometric Approach and Framework Development. Bus. Res. 2018, 12, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylander, A. Design Thinking as Knowledge Work: Epistemological Foundations and Practical Implications. Des. Manag. J. 2009, 4, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Raghallaigh, P.; Sammon, D.; Murphy, C. The Design of Effective Theory. Syst. Signs Actions 2011, 5, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, U. Design Science Research for Personal Knowledge Management System Development-Revisited. Inf. Sci. 2016, 19, 345–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, K.M. The Importance of Personal Knowledge Management in the Knowledge Society. In Personal Knowledge Management; Gower Publishing: Hampshire, UK, 2011; pp. 229–262. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, C. Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, from Atoms to Economies; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kanengisser, D. How Ideas Change and How They Change Institutions: A Memetic Theoretical Framework. In APSA 2014 Annual Meeting Paper; APSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, A.Y.; Massini, S.; Peeters, C. Microfoundations of Internal and External Absorptive Capacity Routines. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senivongse, C.; Bennet, A.; Mariano, S. Utilizing a Systematic Literature Review to Develop an Integrated Framework for Information and Knowledge Management Systems. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2017, 47, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senivongse, C. External Knowledge Absorption in Information Technology Small and Medium Enterprises: Exploratory Multiple Case Studies of the Role of Absorptive Capacity Meta-Routines and Exploratory Regimes. Ph.D. Thesis, Bangkok University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, U. Supporting the Sustainable Growth of SMEs with Content-and Collaboration-Based Personal Knowledge Management Systems. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, M. Digital Divide, Knowledge and Innovations. J. Inf. Inf. Technol. Organ. 2013, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K. Three Worlds: The Tanner Lecture on Human Values: Delivered at the University of Michigan; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Beinhocker, E.D. The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamori, Y. Knowledge Science: Modeling the Knowledge Creation Process; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kameoka, A.; Wierzbicki, A.P. A Vision of New Era of Knowledge Civilization; JAIST Press: Kanazawa, Japan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, U. Decentralizing Knowledge Management: Affordances and Impacts. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, V. As We May Think. Atl. Mon. 1945, 176, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, T.H. As We Will Think. In From Memex to Hypertext; Academic Press Professional, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; pp. 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R.; Konno, N. SECI, Ba and Leadership: A Unified Model of Dynamic Knowledge Creation. Long Range Plann. 2000, 33, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Theory of Affordances; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.: Hilldale, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe, G. Complex Adaptive Digital Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the International ACM Conference on Management of Emergent Digital EcoSystems, Bangkok, Thailand, 26–29 October 2010; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, U. Devising Enabling Spaces and Affordances for Personal Knowledge Management System Design. Inf. Sci. 2017, 20, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signer, B. What Is Wrong with Digital Documents? A Conceptual Model for Structural Cross-Media Content Composition and Reuse. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Conceptual Modeling, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1–4 November 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 391–404. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, U. Rationalizing a Personalized Conceptualization for the Digital Transition and Sustainability of Knowledge Management Using the SVIDT Method. Sustainability 2018, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, A.P. A History of Mechanical Inventions; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsford, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Völkel, M. Personal Knowledge Models with Semantic Technologies; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dalkir, K. Knowledge Management in Theory and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M. Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes and Good Ideas. Am. J. Sociol. 2004, 110, 349–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, J. Exploring Knowledge Creation Processes as a Source of Organizational Learning: A Longitudinal Case Study of a Public Innovation Project. Scand. J. Manag. 2017, 33, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.; Cohen, J. Figments of Reality: The Evolution of the Curious Mind; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Star, S.L. This Is Not a Boundary Object: Reflections on the Origin of a Concept. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2010, 35, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.W. Digital Threat and Vulnerability Management: The SVIDT Method. Sustainability 2017, 9, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, U. Designing Decentralized Knowledge Management Systems to Effectuate Individual and Collective Generative Capacities. Kybernetes 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Pirolli, P.; Card, S. The Sensemaking Process and Leverage Points for Analyst Technology as Identified through Cognitive Task Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligence Analysis, McLean, VA, USA, 3–4 May 2005; Volume 5, pp. 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Pirolli, P.; Russell, D.M. Introduction to This Special Issue on Sensemaking; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nick, M.; Althoff, K.-D.; Bergmann, R. Experience Management. LWA 2007, 339. Available online: http://www.wi2.uni-trier.de/shared/publications/2007_Experience%20Management%20Schlagwort.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Khriyenko, O.; Khriyenko, T. Innovative Education Environment and Open Data Initiative: Steps towards User-Powered Society-Oriented Systems. GSTF J. Comput. JoC 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, E. A Design Framework for Personal Learning Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, A.; Uebernickel, F. Untangling Generativity: Two Perspectives on Unanticipated Change Produced by Diverse Actors. In ECIS; Boğaziçi University: Beşiktaş, Turkey, 2016; Volume 35. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, U. Interoperability of Managing Knowledge and Learning Processes for Sustainable E-Education. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Next Generation Computing Applications, Balaclava, Mauritius, 19–21 September 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, B. Product Innovation and Market Shaping: Bridging the Gap with Cognitive Evolutionary Economics. Indraprastha J. Manag. 2016, 4, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cantner, U.; Vannuccini, S. A New View of General Purpose Technologies; Jena Economic Research Papers: Jena, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, S. How Digital Communication Technology Shapes Markets: Redefining Competition, Building Cooperation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gratton, L. The Shift: The Future of Work Is Already Here; Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, U. Personal Knowledge Management for Development (PKM4D) Framework and Its Application for People Empowerment. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 99, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Public Knowledge | Private Knowledge | |

|---|---|---|

| Discoverable Knowledge | Information Entropy [1] | Online and Publishing Realities [2] |

| Information Overload (-) | More rapid iterative Improvement (+) | |

| Attention Poverty, Mobility (-) | Innovation & Reputation Systems (+) | |

| Undiscoverable Knowledge | Structural Holes, Islands, Siloes [3] | Invisible Work, Scaffolding [6] |

| Ineffective Utilization [4] | Non-Linear Relationships [7] | |

| Deficient Awareness/Education [5] | Unproductive Rework (-) | |

| Innovation and Opportunity Divides (-) | Holistic Understanding (-) |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmitt, U. (Neg)Entropic Scenarios Affecting the Wicked Design Spaces of Knowledge Management Systems. Entropy 2020, 22, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/e22020169

Schmitt U. (Neg)Entropic Scenarios Affecting the Wicked Design Spaces of Knowledge Management Systems. Entropy. 2020; 22(2):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/e22020169

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmitt, Ulrich. 2020. "(Neg)Entropic Scenarios Affecting the Wicked Design Spaces of Knowledge Management Systems" Entropy 22, no. 2: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/e22020169

APA StyleSchmitt, U. (2020). (Neg)Entropic Scenarios Affecting the Wicked Design Spaces of Knowledge Management Systems. Entropy, 22(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/e22020169