1. Introduction

How can institutions of higher learning in theological education respond to an increasing need for bivocational ministry preparation, training, and support? Lancaster Theological Seminary (LTS) established specific action steps to learn to do so in its Strategic Plan 2020–2022. One of these action steps was to explore options “to equip current and future bivocational religious leaders with ministerial leadership skills”. Toward this end, the seminary applied for and received a matching grant from the In Trust Center for Theological Schools to fund a year-long effort, “Educating for a Thriving Bivocational Ministry” (grant number 202021524). A significant part of this project involved surveying core constituencies of the seminary and hosting a student focus group to learn how the seminary currently supports and equips students for bivocational ministry. Lancaster Theological Seminary is a school of the United Church of Christ and one of approximately 250 member schools of the Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada (ATS). Following this introduction, these findings are presented as a case study.

Bivocational ministry—also called multivocational, covocational, dual career, partially funded, or tentmaking ministry—is not consistently defined in academic literature or popular usage. Thus, one of the first tasks in the seminary’s effort consisted of a review of literature and attempt to define terms (

Stephens 2021). A tentative definition provided initial direction for this grant project. Bivocational ministry was defined as a combination of religious and secular employment (paid or unpaid) by someone called to representative ministry. Bivocational ministry is contrasted with univocational (full-time, fully funded) ministry as well as part-time ministry not accompanied by other significant employment or volunteer work. The research team for the Canadian Multivocational Ministry Project worked from a similar definition, interviewing people who had “more than one job or serious volunteer commitment in addition to a congregational leadership role” (

Watson et al. 2020, p. 5). This researcher prefers the term “bivocational” because it unambiguously connotes pastoral ministry (

Stephens 2021).

In recent years, white Protestants in North America have increasingly expressed interest in bivocational pastors as leading a “new” way of doing ministry in local congregations. Researchers and writers are quick to point out, though, that bivocational pastors have long been the norm in other parts of the world and for many non-white and immigrant communities within North America (

Bentley 2018, p. 148;

Christian Reformed Church in North America 2020, p. 13;

Deasy 2018, p. 66;

MacDonald 2020, pp. 8–9). In 2006, Carroll reported “18% of mainline Protestants, 29% of conservative Protestants, and 41% of clergy in historic Black denominations [were] bivocational” (

Carroll and McMillan 2006, p. 81). While popular perception depicts an increase, the actual percentage of bivocational pastors in the US seems to be holding steady. In an article titled, “Are Bivocational Clergy Becoming the New Normal?” researchers observed no increase between 1996–2017, though statistics varied by gender, marital status, and geographic region (

Perry and Schleifer 2019). According to the “National Congregations Study”, the percentage of congregations served by a “head clergyperson” who “also holds another job” was 37% in 2006–2007, 34% in 2012, and 35% in 2018–2019 (

Chaves et al. 2021, p. 22). Whether their numbers are increasing or holding steady, it is fair to say that bivocational pastors have attracted much more attention in the mainline in recent years.

Increased attention has prompted greater awareness of the distinct challenges and stressors on bivocational pastors and congregations. Finances are, of course, a stressor for pastors juggling part-time employments, but this is neither the only nor the most significant source of stress. Consistently, part-time or bivocational pastors report being less valued and supported within denominational structures and congregations (

Carroll and McMillan 2006, p. 175;

MacDonald 2020, pp. 23–28;

Miller-McLemore 2008, pp. 166–67). The need to overcome external bias and stigma is accompanied by the individual’s need to balance multiple vocations (

Miller-McLemore 2008, pp. 169–71) or “multiplicity” within a singular sense of vocation (

Lindner 2016). The Canadian Multivocational Ministry Project focused on clergy health and job satisfaction, exploring the ways that multivocational pastors combined various employments to sustain their vocational identities and ministries (

Watson et al. 2020, pp. 16–18). A significant aspect of thriving was intentionality—discerning a “unique fit” for ministry, employment, and the individual’s gifts (

Watson et al. 2020, p. 18). Samushonga’s observation in the United Kingdom is applicable in North America, as well: “there is an emerging concept of

intentional bivocationalism” (

Samushonga 2019, p. 77). For congregations accustomed to the “standard model” of professional ministry, adjusting to bivocational ministry requires more than a lower salary and reduced hours. Intentional bivocational ministry is a paradigm shift toward shared, congregational ministry (

Bentley 2018, p. 147;

Bickers 2007, p. 6;

Edington 2018, Introduction, p. 8;

MacDonald 2020, p. 65;

Pappas et al. 2009, p. 15;

Stephens 2021;

Watson et al. 2020, p. 19). Thus, intentional bivocational ministry also requires changes in perception and expectations, including adjustments to congregational leadership style (

MacDonald 2020, pp. 65–69;

Watson et al. 2020, p. 19).

The emergence of intentional bivocationalism challenges ATS member schools to become more intentional in their efforts to prepare students for bivocational ministry. In 2011, Daniel O. Aleshire, then Executive Director of ATS, observed that “the percentage of part-time pastors has emerged as a growth industry in mainline Protestantism across the past two decades” (

Aleshire 2011, p. 76). However, most bivocational pastors seek training outside of accredited master’s degree programs and many are credentialed through pathways other than ordination. The usual channels for intentional preparation for bivocational ministry are found beyond ATS member schools (

Aleshire 2010, p. 511;

González 2020;

Scharen and Miller 2016, p. 8). Similar challenges exist in the United Kingdom (

Samushonga 2020). Researchers in the Canadian Multivocational Ministry Project concluded, “the increasingly diverse and constantly changing nature of ministry calls for more regular curricular review and a constant evaluation of delivery formats” (

Chapman and Watson 2020, p. 12). ATS member schools are feeling some pressure to adapt. Current Executive Director of ATS, Frank Yamada, observed that this generation of theological students are increasingly part-time and “already engaged in a local ministry context while working on a degree” (

Yamada 2020, p. 32). Theological schools are addressing these changes in structured as well as improvisational ways as they learn to meet the needs of bivocational students and pastors.

Lancaster Seminary is not alone among in turning its attention to bivocational ministry. Aleshire cited positive examples of ATS programs that cater primarily to bivocational students, one of which required students to be employed at least half-time in ministry while completing their degree (

Aleshire 2021, pp. 108–9). Other schools have investigated balancing dual roles (

Grand Rapids Seminary 2018), financial stability of bivocational pastors and congregations (

Bentley 2018), and joys and challenges of bivocational ministry (

Earlham School of Religion 2016). ATS seminaries seeking to meet the needs of bivocational students and prepare students for bivocational ministry are, for the most part, faced with two main avenues for change: create and nurture “alternative educational models” falling outside the scope of ATS-accredited degree programs (

Aleshire 2008, p. 137; see also

González 2015, p. 139;

MacDonald 2020, pp. 111–21) or adapt the curriculum and delivery of master’s degree programs. Lancaster Seminary has done both in recent years. Six years ago, this seminary lowered the number of credits required and developed a four-year “weekend” (Friday evening and Saturday morning) track for the Master of Divinity degree. While this track is technically not a part-time program, the intention was to cater to students who work and go to school. Two years ago, this seminary launched a part-time, non-degree program for lifelong learners preparing for ordination without going to seminary. However, neither program is explicitly promoted as bivocational.

To improve its support for bivocational students and better prepare them for bivocational ministry, Lancaster Seminary surveyed current students, staff, faculty, and trustees and conducted a series of six focus group meetings with students. This research focused implicitly on this seminary’s degree programs. Survey questions pertained to perception and relevance of bivocational ministry, distinct stressors of bivocational ministry, opinions about current degree programs at the seminary, and opinions about institutional changes designed to better support and prepare seminarians for bivocational ministry. This article presents the findings of these surveys, augmented with data from a series of student focus group meetings. The article concludes with a discussion of challenges and opportunities facing this seminary in its strategic effort to educate for a thriving bivocational ministry, with implications for theological education in general.

2. Methodology Overview and Demographics

Between the dates 19 November 2020 and 3 December 2020, the project director administered four surveys, each to a different constituency of Lancaster Seminary (

Supplementary S1). The project received prior approval for human subject research. Surveys of current students and faculty (adjunct faculty as well as fully funded faculty) were conducted through the seminary’s learning management system, Moodle. Surveys of staff and trustees were conducted through Google Forms. The entire population invited to participate consisted of 186 persons: faculty (38), staff (29), students (98), and trustees (21). A significant proportion participated: faculty (32%), staff (45%), students (22%), and trustees (38%). In aggregate, N = 55, consisting of faculty (12), staff (13), students (22), and trustees (8).

Demographic information was collected on all respondents except trustees (so as to maintain greater anonymity among this smaller group). Of those surveyed, 18% of student respondents identified as “BIPOC or Latinx”, compared to 43% BIPOC or Latinx among the entire student body (

Lancaster Theological Seminary 2020). Of all constituents surveyed, 21% identified as “BIPOC or Latinx”, 70% of whom answered affirmatively when asked if they were “affiliated with a US mainline, historically white denomination (UCC, UMC, ECUSA, PCUSA, etc.)”. Among all respondents, 79% were affiliated with a white, mainline denomination; inferred is that about 15% of respondents were white persons in a nondenominational, multiethnic, multiracial, or no church setting. Students were also asked their preferred pronouns: they/them/theirs (0); she/her/hers (7); he/him/his (11); four did not answer. At the time of the survey, 51% of the entire student body was female (

Lancaster Theological Seminary 2020). Most student respondents were in master’s degree programs (19); three were in the Doctor of Ministry program.

Vocationally, staff and faculty respondents were asked if they were “ordained, licensed, or in some form of authorized ministry in [their] faith community”: over half said yes, with faculty (9 yes; 3 no) outnumbering staff (5 yes; 8 no) in their affirmative responses. Just over one-third of staff and faculty respondents answered affirmatively to the prompt, “I consider myself a bivocational minister (or have significant previous experience as a bivocational minister)”: again faculty (7 yes; 5 no) outnumbered staff (2 yes; 11 no) in their affirmative responses. Among staff and faculty, all who were bivocational were in some form of authorized ministry and 64% of those in authorized ministry were currently or previously bivocational ministers.

The sample of students surveyed skewed more active in ministry and other employments than expected, based on recent Graduating Student Questionnaires (GSQs) for Lancaster Seminary. Two-thirds of student respondents “currently hold a paid position outside of ministry” (Q23 for students), and 55% “currently hold a paid ministry position” (Q22 for students). While 55% of student respondents described their current ministry as bivocational (Q24 for students), not all students holding a paid ministry position considered themselves bivocational. Nearly 60% of current student respondents “expect to be bivocational in ministry after graduation” (Q25 for students)—twice the rate reported on the GSQ over the previous seven years (

ATS n.d.; see also

Deasy 2018, p. 66).

1Almost all the students participating in focus group meetings were engaged in some form of paid employment, ministerial or otherwise, while attending seminary. Each monthly focus group meeting lasted one hour and was conducted via Zoom. Thirteen students participated in at least one of the six focus group meetings over a span of six months. Meetings were held 10 November and 15 December 2020, and 18 January, 9 February, 9 March, and 13 April 2021. Ten students attended at least three meetings. The group included significant gender and racial diversity: preferred pronouns included 5 she/her, 7 he/him, and 1 they/them; racial representation included 7 Black and 6 white students; and one student identified as Latino. Ages ranged from 20 s to 60 s.

Survey instruments are provided in the

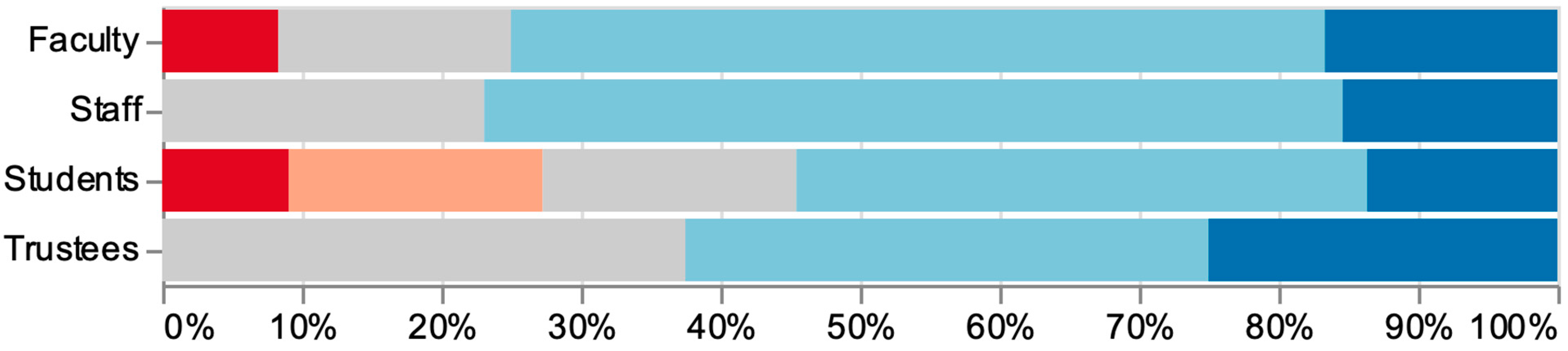

Supplementary S1. The first 17 questions were identical on all four surveys and utilized the same Lickert scale:

strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree. Responses are reported below in the form of color-coded charts (

Figure 1). Additional questions were asked separately of each constituency.

The following analysis presents the findings of these surveys (

Supplementary S2), arranged in four sections: perception and relevance of bivocational ministry, distinct stressors of bivocational ministry, opinions about current educational programs at the seminary, and opinions about institutional changes.

3. Perceptions about Bivocational Ministry and Its Relevance

All groups surveyed perceived bivocational ministry as relevant to the future of the church, even if they expressed ambivalence about this future. Across constituencies, 2 in 3 persons agreed that “bivocational ministry is the future of pastoral ministry” (Q1) (

Figure 2). Staff and students exhibited the greatest intergroup and intragroup disparities. Among students, over 75% agreed; among staff, just over 50% agreed. Approximately 5% of staff and students strongly disagreed. Interestingly, the one student who expressed strong disagreement with Q1 also indicated that bivocational ministry is a first choice for their ministry career (Q19 for students), discussed below.

Respondents seemed less than enthusiastic about this perceived future. Among faculty and trustees, only one person agreed that “bivocational ministry is preferable to fully-funded ministry” (Q2); over 85% disagreed and, among faculty, 25% strongly disagreed. Overwhelmingly, faculty and trustees expressed preference for the model of fully funded ministry. Students and staff expressed greater ambivalence. Among students, nearly 60% did not disagree, and over 30% agreed. The gap between student preference for bivocational ministry and that of faculty and trustees was over 40%.

Separately, students were asked if they were intentional about pursuing bivocational ministry (Q19 for students). Student responses were nearly evenly distributed across the entire spectrum of choices (

Figure 3). The disparity in student responses to Q1 and Q19 is remarkable. There is a significant cadre of students (approximately 45%) who see bivocational ministry as the future yet do not prioritize being part of this future. Nevertheless, nearly 60% of student respondents indicated that they “expect to be bivocational in ministry after graduation” (Q25 for students).

All groups perceived bivocational ministry to be an intentional career path with vocational integrity (

Figure 4). Approximately 75% of faculty and staff agreed that “bivocational ministry is an intentional career path for ministry” (Q6); 2 in 3 trustees and a majority of students also agreed. There was no disagreement among staff and trustees; however, 1 in 4 students disagreed.

Regarding vocational integrity, 87% of respondents disagreed that “bivocational ministry is a lesser commitment to one’s call compared to fully-funded ministry” (Q5); approximately 50% strongly disagreed (

Figure 5). Interestingly, the three students who agreed or strongly agreed with this statement (Q5) also agreed or strongly agreed that bivocational ministry is the future of pastoral ministry (Q1).

Across constituencies, bivocational ministry seemed to be valued as a distinct and legitimate form of ministry appropriate to all demographics. Over 60% agreed that “bivocational ministry is a way to model for laity the ministry of all Christians” (Q7); only about 15% disagreed. Regarding skills and preparation, 80% disagreed and nearly 60% strongly disagreed that “bivocational ministry is a path for persons with insufficient skills to enter fully-funded ministry” (Q8). Staff and students showed greater ambivalence than other groups: about 30% of staff were neutral, and 14% of students agreed. Furthermore, only 10% of respondents agreed that “bivocational ministry is a short-term necessity when searching for a full-time church position” (Q3).

None of the groups surveyed considered bivocational ministry to be narrowly relevant based on race, ethnicity, denomination, or the pastor’s experience or life circumstance. Overwhelmingly, all constituencies disagreed that bivocational ministry is: “mainly for second-career pastors” (Q10); “mainly for young, single pastors” (Q11); “mainly for certain faith traditions” (Q12); and “mainly for certain racial or ethnic communities” (Q13). Of the 55 total respondents, only one person agreed with any of these statements; 75% of staff, 95% of students, 98% of faculty, and 100% of trustees disagreed or strongly disagreed with these statements.

Congregational size seemed to have slightly more, though still limited, relevance than any of the preceding factors. In response to the prompt, “Bivocational ministry is only relevant to small congregations that cannot afford a full-time pastor” (Q9), about 40% of staff and trustees were neutral, two faculty persons agreed, and one student strongly agreed. Given another opportunity, this researcher would rephrase the question to say “mainly” rather than “only”.

4. Stressors Faced by Bivocational Students and Ministers

Bivocational ministry was perceived by most to be more stressful than fully funded ministry (

Figure 6). Of all the groups surveyed, students were the least likely to think so, though student opinions were evenly divided. Most faculty, staff, and trustees said yes. Students expressed less agreement than any other group with the statement, “Bivocational ministry is more stressful than fully-funded ministry” (Q4). About 35% of students agreed, compared to 50% of the faculty, 60% of staff, and over 75% of trustees. Notably, about 1 in 3 students disagreed, mirroring the number who expressed preference for bivocational over fully funded ministry. (However, there was no correlation between individual student agreement on Q2 and response to Q4.)

Staff and faculty had no difficulty naming examples of the sources of this stress. In an open-response question, they were prompted to identify “three distinctive stressors faced by bivocational students” (Q18 for faculty; Q22 for staff). All faculty respondents provided answers to this prompt; 9 of 13 staff respondents provided answers to this prompt. In decreasing order of frequency, respondents mentioned: time management; workload and balance; money and finances; professional clarity; and family and health. Nearly every respondent mentioned the challenge of time management or scheduling as a distinct stressor (11 of 12 faculty; 7 of 9 staff). Most also mentioned workload, balance, divided focus, or boundaries as a distinct stressor (6 of 12 faculty; 7 of 9 staff). Money and finances were the third most frequently cited concerns (4 of 12 faculty; 6 of 9 staff). Many respondents also mentioned either issues of professional clarity, such as perceptions/stigma, unrecognized competencies, and career steps (3 of 12 faculty; 2 of 9 staff) or the cluster of concerns about family, personal life, and health (3 of 12 faculty; 2 of 9 staff), though no one mentioned both.

Students participating in the series of focus group meetings also provided insight on bivocational stressors. Over the span of six sessions, they mentioned a variety of challenges facing bivocational students: balancing family, school, and ministry; setting boundaries, staying healthy, and delegating ministry tasks; finances (both personal and church); congregational expectations; and how the COVID-19 pandemic changed the way people work and relate to each other. Several mentioned high expectations for pastors in African American and Latino communities to be available for all major events and to be present in every community function. One Latino student observed that it is disrespectful to have an outsider or an associate pastor perform the duties of the lead pastor. An African American student noted that because pastors are often the most educated persons in the community, the congregants value the pastor’s input. These expectations place tremendous pressure on pastors, most of whom are bivocational, when serving these communities. The expectation to perform to high standards was perceived among all racial and ethnic groups. One student admitted, “Some of us want to take on the ‘Old School responsibilities,’ to do it all as we were taught by our pastors and not to delegate to others”. Anther students observed differences in expectations based on the size of the congregation. “Larger churches have various leaders, different roles/positions and the structure is passed down to the next leaders. Larger church members do not express the same level of need as those of small churches”. As a group, these students evidenced keen awareness of the challenges and contextually specific expectations of bivocational ministry.

5. Educational Programs at Lancaster Theological Seminary

Opinions were mixed regarding Lancaster Seminary’s current efforts to meet the needs of bivocational students. Students, staff, faculty, and trustees were surveyed about the seminary’s current efforts. Additionally, staff and trustees were asked whether the seminary should improve its efforts in the same areas. Of all the groups, trustees were the most reluctant to disagree with statements about the seminary’s positive efforts and the most willing to acknowledge that the seminary should improve the way it meets the needs of bivocational students. A majority of staff and trustees agreed that the seminary should improve its efforts in all of these areas, with only one respondent disagreeing with any of these questions.

Lancaster Seminary seems to offer helpful scheduling choices for bivocational students, with room for improvement. Most respondents agreed that “Lancaster Seminary already does a good job catering to the needs of bivocational students through scheduling choices” (Q15). Trustees believed this more than other groups: 75% agreed and none disagreed. Among faculty, 2 in 3 agreed, and only 15% disagreed. Staff and students showed a wider variety of opinion, though only 25% disagreed. When asked whether the seminary “should improve the way it meets the needs of bivocational students through scheduling choices” (Q19 to staff and trustees), staff and trustees responses aligned: over 50% agreed, and none disagreed.

Opinions varied widely regarding the current academic curriculum, with most responses neutral, though many felt the seminary should improve in this area. About 30% of faculty and staff agreed that the seminary “already does a good job catering to the needs of bivocational students through academic curriculum” (Q14); less than 20% of students and only one trustee agreed (

Figure 7). Among all respondents, 24% disagreed to some extent. Faculty were decidedly mixed in their opinion of the academic curriculum: four disagreed; four were neutral; two agreed; and two strongly agreed.

Staff and trustees overwhelmingly (over 70%) agreed that the seminary “should improve the way it meets the needs of bivocational students through academic curriculum” (Q18 to staff and trustees); none disagreed (

Figure 8).

In a multiple-choice inquiry, faculty indicated that they “currently prepare students for bivocational ministry” (Q21 for faculty) through various means, checking all options provided with approximately equal frequency: case studies, assigned readings, assignments, classroom discussion, academic advising, Comprehensive Vocational Review, and “scheduling, deadlines, and expectations for completing classroom and academic requirements”. No faculty respondents utilized the open-ended “other” option for this question.

Regarding co-curricular offerings, again, opinions varied widely, most responses were neutral, and there was a general perception that the seminary should improve in this area. Faculty and trustees rated the seminary’s efforts more positively than did staff and students. About 35% of faculty and trustees agreed that the seminary “does a good job catering to the needs of bivocational students through co-curricular offerings” (Q17); just over 10% of staff and students agreed. Staff expressed the most disagreement (about 30%) and the least agreement. A majority of staff and trustees agreed that the seminary should improve in this area (Q21 to staff and trustees); only one person disagreed.

Staff and faculty seemed to have difficulty naming specific examples of current co-curricular support for bivocational ministry. When asked to “name three co-curricular experiences supportive and modeling of bivocational ministry” in an open-ended response (Q20 for faculty), only 3 of 12 faculty responded with examples (adjunct faculty; chaplains, preachers and presiders in chapel; field education); three responded that they did not know or were unsure; six offered no response. The same open-ended inquiry was posed to staff (Q24 for staff): one respondent stated, “our adjuncts provide good models for this”; another answered, “Our co-curricular offerings are bare because we have not yet found a way to get students to participate in them”; nine persons replied, “not sure”, or provided no response.

Regarding student services, once again opinions varied widely. Separate questions addressed current student services and the need for improvement. Students rated the seminary’s current efforts more positively than did the other groups: 27% of students agreed that the seminary “already does a good job catering to the needs of bivocational students through student services” (Q16); only 12% of other respondents agreed. About 22% of all respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed; 60% of responses were neutral. Staff and trustees were asked an additional question about the need for improvement. A majority of staff and trustees agreed that the seminary should improve in this area (Q20 to staff and trustees); none disagreed.

Faculty and staff named many specific examples of student services supportive of bivocational ministry. In an open-response question, 50% of faculty and staff offered substantive examples of “advising and student support services for bivocational ministry” at the seminary (Q19 for faculty; Q23 for staff). Both groups named: seminary chaplains, academic [faculty] advisors, field education, Comprehensive Vocational Review, financial counseling and debt reduction program, and after-hours library access. Faculty also named: the dean, other students, library e-resources, Saturday worship, and faculty availability outside standard hours. Staff also named: writing center, four-year [weekend] MDiv program, denominational advisors, registrar, and flexible [staff] schedule. The most often mentioned student support services by the 25 faculty and staff respondents were: seminary chaplains (7); faculty academic advisors (5); field education (3); and student debt reduction program (3). In a multiple-choice inquiry, staff were asked, “How do you currently contribute to the preparation of students for bivocational ministry?” (Q25 for staff): respondents checked all options provided except “lowering my expectations”. The most frequent responses were “shifting my work hours and availability” and “transforming the way I do my job with bivocational students in mind”. No staff respondents utilized the open-ended “other” option for this question.

6. Distinct Viewpoints Shared

Each of the four constituencies—staff, faculty, students, and trustees—offered distinct viewpoints on bivocational ministry and the seminary’s efforts. Survey respondents were given opportunity to voice additional observations, opinions, questions, or concerns in an open-response format (Q26 for staff; Q22 for faculty; Q18 for students; Q26 for trustees). The following discussion characterizes the responses received by each constituency. Analysis of student responses is augmented with detailed feedback from the student focus group participants. Analysis of trustee responses is reported in conversation with trustee responses in other parts of the survey.

6.1. Staff

Staff observed that the concept “bivocational” is not consistently understood even as they affirmed its relevance and posed challenging questions about the seminary’s current programs. One staff person recognized ambiguity in the way the term is often used:

The term bi-vocational is still confusing to me in our seminary context. In many ways, it sounds like bi-vocational is used to describe people working in ministry and get a degree at the same time. At the same time could be understood as people who want to have two careers after seminary.

Another staff person also expressed a desire for definitional clarity. Their concerns are warranted. The literature on bivocational ministry reveals a wide range of uses for the term as well as many other related terms. Researchers, many working on behalf of judicatories or theological schools, often begin with an exploration of the range of definitions and terms (

Bentley 2018;

Deasy 2018;

Samushonga 2020;

Stephens 2021). Nevertheless, the term bivocational held sufficient valence for staff to express opinions and concerns. Another staff person remarked, “Bivocational implies ministry and one other job whereas in different cultures and context the resources for the ministry are vastly different such that the two jobs (ministry and other) can very well be several jobs with full time demands”. Culture and context are indeed significant for the practice and prevalence of bivocational ministry, particularly when race, gender, and ethnicity are considered (

Bentley 2018, p. 148;

Deasy 2018, pp. 66, 69;

MacDonald 2020, pp. 8–9;

Perry and Schleifer 2019). The staff person who is quoted above about definitional confusion also spoke frankly about economic need: “In some cases, bi-vocational ministry is not a choice but rather an unfortunate reality of economic inequality”. The same person also raised the issue of vocational coherence and integrity. “Integrating bi-vocational ministry into our seminary[we] should be asking questions [such as,] How can a Pastor/Faith leader/Social activist always be that in all spaces?” This person also questioned the ability of existing degree programs to mee the needs of bivocational students, citing the limited number of electives, the high cost of an MDiv, as well as the need to explore dual programs in social work, law, non-profit leadership, and so forth.

6.2. Faculty

Faculty responses indicated a spectrum of attitudes, ranging from complacency to avoidance to defense, revealing no concerns about the existing curriculum. One observed, “Many aspects of an LTS education are applicable to both single-vocational and bi-vocational ministry”. Another admitted, “we at Lancaster Theological Seminary are still more focused on ministry as a full time vocation than we are aware of bivocational ministry”. In fact, despite a commitment to bivocational ministry preparation in the institution’s strategic plan, one faculty person observed, “I do not recall this issue surfacing in faculty and/or staff meetings”. Yet, another confessed the complexity of bivocational ministry: “There are many variables in regard to this issue; it is almost impossible to generalize”. These attitudes sat alongside other comments, which seemed to focus attention and responsibility elsewhere. One rued the difficulty of “maintain[ing] high pedagogical standards” with students struggling “to balance a full time job with studies, ministry, and family responsibilities”. Another cast attention on the church rather than the seminary.

Sometimes bivocational ministry is how congregations and the wider church can benefit from the breadth of gifts that ministers bring to the table … the church recruits people to ministry for their gifts, and then promptly asks them to stop practicing that gift and “do ministry” instead. The church would best benefit by making room for the minister to serve the church as well as continue growing and practicing in their area of talent.

This may well be true of many churches. Yet, the observation deflected attention from the seminary and its role in supporting bivocational students and pastors. Missing from faculty comments was any discussion of what this institution of theological education might do differently to better educate for a thriving bivocational ministry.

6.3. Students

Students, more than any other group, defended the legitimacy of bivocational ministry and voiced appreciation to the seminary for raising the visibility of this form of pastoring. Of the seven students who offered a free response, three provided a justification for bivocational ministry. “Multi vocational ministry is a viable calling for serving the kingdom and maybe the way in which those who are called to serve can serve”, commented one student. Another stated, “I believe it is another form of living out a call and isn’t lesser than full time ministry—just different. I believe it can be in many different forms”. Clearly, these students felt the need to defend bivocational ministry as “a viable calling” that is not “lesser than” univocational career paths. Yet, another student remarked, “Bivocational ministry is not a new concept. While the term may have not be used in decades earlier, some ministers have always had two or more careers”. This student drew attention to the fact that the newness is not the practice in the church but rather the awareness of this practice on the part of professional theological educators and the full-time, professional pastors they have trained over the years. Two students also thanked the seminary for its efforts in this area, and another indicated that the conversation about bivocational ministry was personally relevant to their professional discernment. As if to summarize the sentiments voiced by students, one remarked, “This should be an orientation topic for new students or prospective students”.

Students participating in the focus group expressed a range of ideas for improving the way the seminary supports bivocational students and prepares them for bivocational ministry. Students identified several challenges, including the availability of student services, scheduling difficulties, field education placements, and boundaries between personal and professional realms. When asked about their needs as bivocational students, they mentioned the need for: better communication about student workload and degree program expectations; transition support for second-career students and bivocational students; courses on finances, budgeting, entrepreneurship, and fundraising; and bivocational student advising. When asked how the seminary might better serve and equip future bivocational students, participants offered specific ideas: the importance of; the need to incorporate practical experiences, such as mock weddings or baptisms, with some of the courses; not assuming that every student comes to seminary with church background and practical knowledge of congregational life; more availability of administrative staff on the weekends; early advisement on field education and CPE options; and counseling, resources, and support for family members of bivocational students.

6.4. Trustees

Trustees showed a combination of caution and openness to institutional change. In open-ended comments, one expressed a need for more research to better understand the issue.

As a member of the board of trustees, I realize I actually have very little information about how bivocational students and alumni feel about how LTS served them. I am unable to comment on recommended institutional changes without understanding better what we know about how we are currently doing with preparing students for bivocational ministry.

The approach is prudent; indeed, the very motivation for the present grant-funded project was to conduct research on these and other questions. Another trustee wasted no time in advocating for institutional change: “We need to raise the value of a pathway to ministry as a bivocational option. LTS could work with judicatories to create the training for these roles just like they did for alternate paths to ordination”. This response requires some knowledge of institutional background for interpretation. Regarding training, the trustee drew a comparison to the seminary’s new program of lifelong learning, which was created in response to recent changes in the United Church of Christ that allow candidates for ordination to fulfill educational requirements without earning an MDiv or attending seminary. Thus, this trustee was suggesting that the institution think outside of current degree program offerings as it educates persons for bivocational ministry

Trustees were also given an opportunity through other parts of this survey to express their opinions about prioritizing specific institutional changes to promote and support bivocational ministry at the seminary. Exactly 50% agreed that the seminary should “create a program designed with the needs of bivocational students in mind” (Q23 for trustees) and “encourage students to consider a bivocational career path in ministry” (Q24 for trustees). Only one trustee disagreed with these statements. Furthermore, 75% agreed that the seminary should “raise the profile of bivocational ministry as a legitimate and vital form of leadership for the church” (Q25 for trustees), and 25% strongly agreed with this statement. However, ambivalence surfaced when trustees were asked about recruitment. Only 25% agreed that “Lancaster Seminary should prioritize institutional changes in order to recruit bivocational students” (Q22 for trustees); the remaining respondents were neutral.

The trustees presented a complicated picture of institutional response. On the one hand, they agreed that the institution should encourage bivocational career paths and bolster the legitimacy of this path. On the other hand, they implied that the seminary should do so outside of its existing degree programs. Would this combination of sentiments explain why trustees responded so affirmatively to institutional improvements yet expressed reluctance to recruit bivocational students?

7. Educating for a Thriving Bivocational Ministry

The preceding data and analysis provided a fine-grained picture of perceptions, attitudes, and opinions about bivocational ministry and seminary education according to four groups of constituents at Lancaster Seminary. This picture closely aligns with the existing literature, helping theological educators to understand the challenges and opportunities facing bivocational students and students preparing for bivocational ministry. These findings are indicative rather than definitive, inviting further research involving more schools and a larger set of respondents.

Perceptions of and attitudes about bivocational ministry were characterized by ambivalence. Many recognized the need for bivocational ministry even as they expressed no desire to be bivocational. All constituencies surveyed valued bivocational ministry as a distinct and legitimate form of ministry with vocational integrity. However, many expressed personal ambivalence about being bivocational. Students expressed the entire range of responses when asked if they were intentional about pursuing bivocational ministry. Nearly 70% of all constituents surveyed viewed bivocational ministry as the future of pastoral ministry; yet, faculty and trustees overwhelmingly preferred the model of fully funded ministry. What does it mean that so many acknowledge the importance of a form of ministry that is different from their preferred form of leadership? Students and staff were less certain about this preference; were they just being more realistic than faculty and trustees about the employment options available to seminary graduates?

Theological educators seeking to respond to an increasing need for bivocational ministry preparation, training, and support will have to address ambivalence directly. Intentional efforts to expose existing negative perceptions and to destigmatize bivocational ministry are needed to validate and support students in bivocational ministry. These efforts must address attitudes internal to the institution, as well. If faculty and trustees harbor a full-time bias, the school should not be surprised if its students express ambivalence about bivocational ministry as a preferred career option. The bias against part-timers runs deep in higher education, as any contingent faculty member can attest. While one staff person suggested that adjunct professors provide a positive model of bivocationality, it is no secret that adjuncts suffer from significant institutional injustices (see, for example,

Gaudet and Keenan 2019). This implicit curriculum must be changed if schools desire to promote bivocational ministry as a valued pathway for ministry. Significantly, students evidenced a need to defend the legitimacy of bivocational ministry in their survey responses. They also expressed appreciation to the seminary for raising the issue through this research. Though student focus group participants were paid a small stipend, it was clear that they valued the experience for more than the money. The focus group become a support group for students experiencing and exploring bivocational ministry. Through both the focus group and the survey instrument, the research itself seemed to fulfill a need for students, validating and supporting them in a form of ministry that holds distinct challenges and stresses.

This research confirmed the challenges and stressors most often cited in the literature on bivocational ministry, sometimes heightened by the seminary experience. Those surveyed mentioned financial pressures, inadequate professional support, negative perception and stigma, and the importance of intentionality and fit, balance and vocational integration, and renegotiating congregational expectations. At least two staff persons shared keen observations about economic inequality, the difficulty of vocational integration and pastoral identity in multiple spheres, the relevance of cultural context, and the need for definitional clarity of the term bivocational. Addressing intentionality and fit is also important to health and flourishing of the bivocational pastor (

Watson et al. 2020, p. 18). However, as implied by the survey data, it is difficult to be intentional about a future vocation for which one feels tremendous ambivalence. The ability to discern a unique and appropriate fit for the individual in bivocational ministry is premised on bivocational ministry being valued and supported as a preferred career option.

The stresses of bivocational ministry are evident throughout the seminary experience. Students face these challenges not only in future bivocational ministry positions but also as students balancing schoolwork, family, jobs, and churchwork. In addition to pressures relating to the practical matters of finances, scheduling, and workload, seminary students actively seek vocational clarity while participating in an intense process of spiritual formation and discernment. Participants in the student focus group also revealed that many of these stressors are exacerbated by differences in privilege due to race, gender, and class. As do many ATS programs, this school provides programmatic guidance for vocational discernment, integration, and review. However, if bivocational ministry is not an explicit part of this structured experience, bivocational students may perceive these programmatic features of the degree program as irrelevant or antagonistic to bivocational integration and clarity.

Survey respondents named stressors and challenges more readily than the skills needed to address them. One item in the literature not evident in the data collected was the need for different pastoral leadership styles in bivocational congregations as contrasted with congregations that employ a full-time pastor. Knowing this difference is a matter of leadership skill. Based on the 2017 ATS Graduating Student Questionnaire (GSQ), ATS researcher Jo Ann Deasy posed the following questions regarding skills development:

The growing number of graduates going into bi-vocational ministry raises several questions about theological education. … What are the unique skills needed to prepare someone for bi-vocational ministry? Are there particular ways of thinking that need to be cultivated? Are there ways to help students develop a portfolio of skills that will allow them to structure a bi-vocational life that can support them financially? Should theological schools develop part-time programs that intentionally teach students how to live and think bi-vocationally as they balance work and school?

Deasy’s questions about skills development remain only partially addressed by the current research. Distinctive skills and mindsets helping to structure a successful bivocational ministry can only be inferred from the survey data. Furthermore, bivocational ministry as such is under-researched; there is a paucity of literature on the skills needing cultivation.

Survey data revealed wide disparity in opinion about this school’s current academic curriculum as it pertains to bivocational ministry. Of several aspects of this school’s programming, academic curriculum stood out as the area in most need of improvement, according to those surveyed. While the survey responses exhibited a general sense that the academic curriculum should be changed to support bivocational ministry, the survey was not designed to elicit ideas about how it should be changed. Disparity of opinion among the faculty about the academic curriculum combined with their overall preference for full-time ministry portend difficult conversations about the desirability of reshaping academic offerings to support bivocational ministry. One staff person questioned the ability of the current degree program to address the challenges faced by bivocational students. Furthermore, trustees voiced reluctance to prioritize recruiting bivocational students even though this seminary already offers a weekend schedule for its MDiv curriculum designed for students holding a job while attending school. Trustees were, however, in favor of creating a program with bivocational students in mind. There may be a significant number of faculty and trustees who consider bivocational ministry preparation more appropriate for this school’s non-degree program of life-long learning than for its master’s level degree programs, as suggested by one trustee. This is an important conversation to pursue.

Lancaster Seminary is well-positioned to address Deasy’s last question, about part-time programs of theological education. Most survey respondents agreed that the school supports bivocational students through scheduling choices, and most staff and trustees agreed that the seminary should improve in this area. This seminary’s “weekend” track for the Master of Divinity degree has been successful enough to overshadow the more traditional, three-year “weekday” option; however, more effort is needed to meet the needs of bivocational students. The weekend program could be improved, in Deasy’s words, by “intentionally teach[ing] students how to live and think bi-vocationally as they balance work and school” (

Deasy 2018, p. 70). It is not enough merely to change the schedule to accommodate working students; bivocational ministry preparation requires intentional reflection on the schedule and what it means for students vocationally. Only about 10% of staff and students agreed that this seminary’s co-curricular offerings meet the needs of bivocational students. The need to address bivocational ministry intentionally is evidenced in the difficulty staff and faculty had in naming specific examples of current co-curricular support of bivocational ministry. Scheduling and time constraints come into play, as one staff person noted, when students do not show up for the co-curricular activities the seminary offers.

Theological schools will need to explore Deasy’s questions in partnership with students and practitioners as they develop ways to meet the needs of bivocational students and pastors. All constituencies surveyed agreed that student services should be improved. Faculty and staff could name many specific examples of existing student services supportive of bivocational students, and students, more so than any other group surveyed, seemed to think this seminary was already do a good job at this. For example, Lancaster Seminary provides a program of financial literacy and coaching; this research underscores its importance and suggests an expansion of the program may be helpful. The wide array of existing student services and varied opinions about their efficacy indicate that this is an area of this seminary’s offerings that is in generative flux; innovating and refining student services may be an opportunity for creative partnership as this school learns how to teach students to live and think bi-vocationally.

8. Conclusions

Theological educators seeking to improve their preparation, training, and support of bivocational students will have to find ways to address distinct challenges and stressors as well as skills development and perception. Cultivating more positive attitudes and perceptions about bivocational ministry is foundational. The current research inadvertently functioned in this capacity, promoting and legitimating bivocational ministry within this seminary community, suggesting that increased visibility is an important form of support for bivocational students. To be intentionally supportive of bivocational ministry, theological educators must reshape academic curricula to meet the needs of bivocational students. An increasing awareness of the need for bivocational ministry preparation, training, and support should prompt theological schools to partner with students, reflective practitioners, and churches to shape the curriculum in meaningful ways. Not of least importance, the full-time bias within higher education creates a strong implicit curriculum disfavoring bivocational pathways. Can schools that marginalize their contingent faculty promote bivocational ministry with integrity? Furthermore, is bivocational ministry preparation an integral part of degree programs in theological education, or does it belong more appropriately in non-degree programs of life-long learning? ATS member schools will need to decide whether bivocational ministry preparation is an essential or ancillary aspect of their mission as degree-granting institutions as they prepare to educate for a thriving bivocational ministry.