Biocompatible Fe3O4 Increases the Efficacy of Amoxicillin Delivery against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

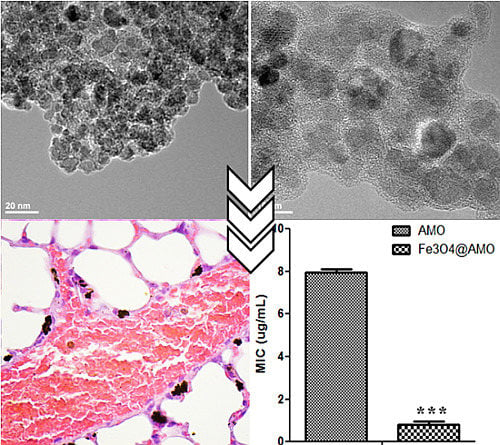

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Synthesis of Magnetite Nanostructures

3.2. Characterization of Magnetite Nanostructures

3.2.1. X-ray Diffraction

3.2.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy

3.2.3. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

3.2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis

3.2.5. Cell Cycle

3.2.6. Cell Viability

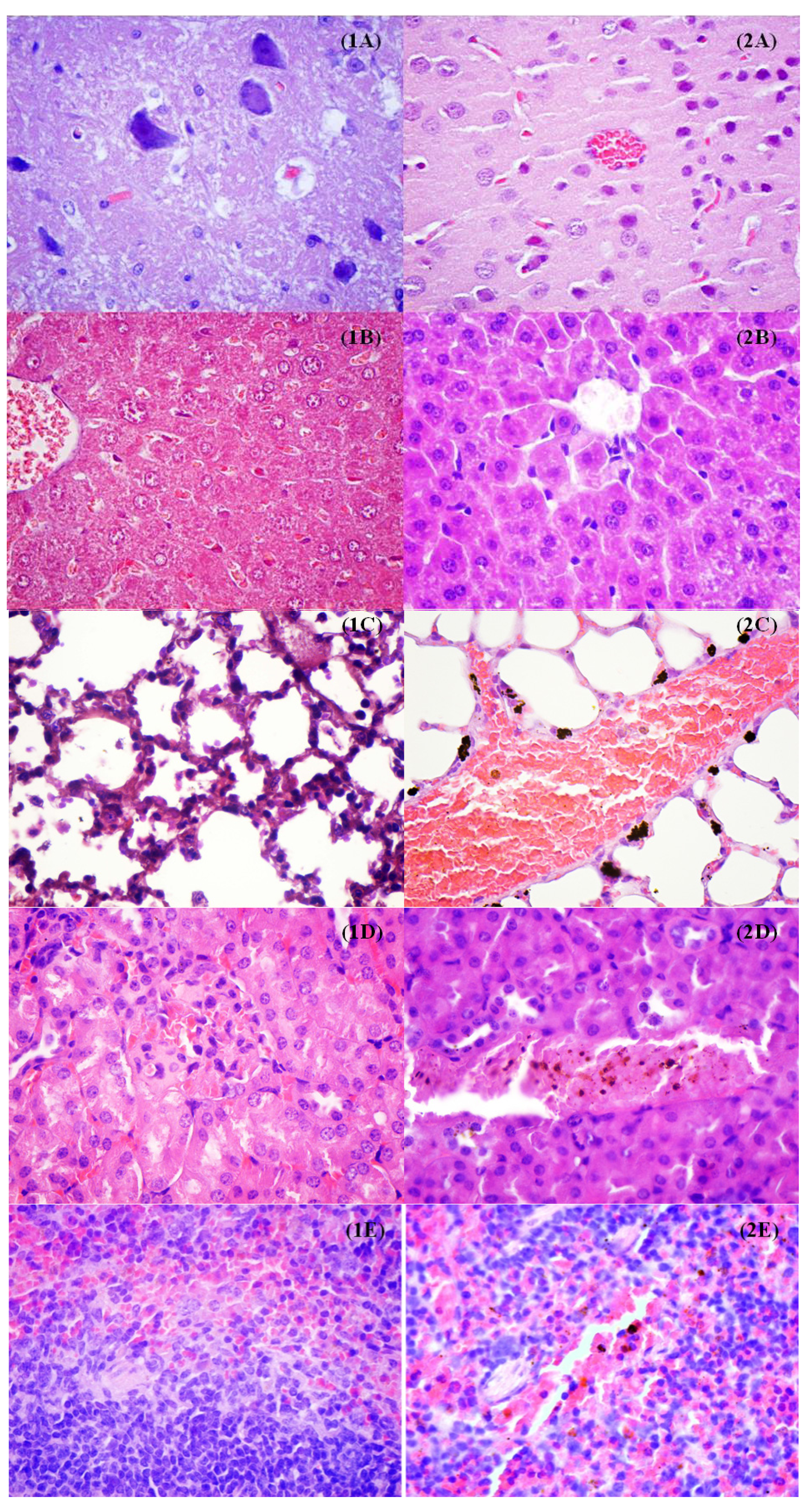

3.2.7. In Vivo Biodistribution

3.2.8. Antimicrobial and Anti-Adherence Assay

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Questions & Answers. In Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work Homepage. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/antibiotic-use/antibiotic-resistance-faqs.html (accessed on 6 June 2009. Retrieved December 2013).

- Cartelle, M.; Canle, D.; Llarena, F.J.; Molina, F.; Villanueva, R.; Bou, G. Characterisation of the first CTX-M-10-producing isolate of Salmonella enterica serotype Virchow. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006, 12, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartelle, M.; del Mar Tomas, M.; Molina, F.; Moure, R.; Villanueva, R.; Bou, G. High-level resistance to ceftazidime conferred by a novel enzyme, CTX-M-32, derived from CTX-M-1 through a single Asp240-Gly substitution. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 2308–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Pierce, J.G.; James, R.C.; Okano, A.; Boger, D.L. A redesigned vancomycin engineered for dual D-Ala-D-Ala and D-Ala-D-Lac binding exhibits potent antimicrobial activity against vancomycin-resistant bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13946–13949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle-Vavra, S.; Daum, R.S. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: The role of Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Lab. Investig. 2007, 87, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodha, S.V.; Lynch, M.; Wannemuehler, K.; Leeper, M.; Malavet, M.; Schaffzin, J. Multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections associated with a national fast-food chain, 2006: A study incorporating epidemiological and food source traceback results. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011, 139, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou, G.; Cartelle, M.; Tomas, M.; Canle, D.; Molina, F.; Moure, R.; Eiros, J.M.; Guerrero, A. Identification and broad dissemination of the CTX-M-14 beta-lactamase in different Escherichia coli strains in the northwest area of Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 4030–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, D.A.; Zhao, S.; Tong, E.; Ayers, S.; Singh, A.; Bartholomew, M.J.; McDermott, P.F. Antimicrobial drug resistance in Escherichia coli from humans and food animals, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, K. Efflux-mediated multiresistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, G.E.; Warren, R.M.; Gey van Pittius, N.C.; McEvoy, C.R.E.; van Helden, P.D.; Victor, T.C. A balancing act: Efflux/influx in mycobacterial drug resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3181–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Vasile, B.S.; Holban, A.M. Eugenol functionalized magnetite nanostructures used in anti-infectious therapy. Lett. Appl. NanoBioSci. 2013, 2, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Holban, A.M.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Andronescu, E.; Grumezescu, V.; Chifiriuc, C.M.; Radulescu, R. Magnetite-usnic acid nanostructured bioactive material with antimicrobial activity. Rom. J. Mater. 2013, 43, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holban, A.M.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Ficai, A.; Chifiriuc, C.M.; Lazar, V.; Radulescu, R. Fe3O4@C18-carvone to prevent Candida tropicalis biofilm development. Rom. J. Mater. 2013, 43, 300–350. [Google Scholar]

- Chifiriuc, M.C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Andronescu, E.; Ficai, A.; Cotar, A.I.; Grumezescu, V.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; Lazar, V.; Radulescu, R. Water dispersible magnetite nanoparticles influence the efficacy of antibiotics agains planktonic and biofilm embedded Enterococcus faecalis cells. Anaerobe 2013, 22, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Cotar, A.I.; Andronescu, E.; Ficai, A.; Ghitulica, C.D.; Grumezescu, V.; Vasile, B.S.; Chifiriuc, M.C. In vitro activity of the new water dispersible Fe3O4@usnic acid nanostructure against planktonic and sessile bacterial cells. J. Nanopart. Res. 2013, 15, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotar, A.I.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Huang, K.-S.; Chifiriuc, C.M.; Radulescu, R. Magnetite nanoparticles influence the efficacy of antibiotics against biofilm embedded Staphylococcus aureus cells. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2013, 3, 559–565. [Google Scholar]

- Cotar, A.I.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Andronescu, E.; Voicu, G.; Ficai, A.; Ou, K.-L.; Huang, K.-S.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Nanotechnological solution for improving the antibiotic efficiency against biofilms developed by gram-negative bacterial strains. Lett. Appl. NanoBioSci. 2013, 2, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Andronescu, E.; Grumezescu, V.; Bleotu, C.; Saviuc, C.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Chifiriuc, C.M. Biocompatible magnetic hollow silica microspheres for drug delivery. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013, 17, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Andronescu, E.; Ficai, A.; Ficai, D.; Huang, K.S.; Gheorghe, I.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Water soluble magnetic biocomposite with potential applications for the antimicrobial therapy. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2012, 2, 469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Holban, A.M.; Andronescu, E.; Ficai, A.; Bleotu, C.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Water dispersible metal oxide nanobiocomposite as a potentiator of the antimicrobial activity of kanamycin. Lett. Appl. NanoBioSci. 2012, 1, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Andronescu, E.; Holban, A.M.; Ficai, A.; Ficai, D.; Voicu, G.; Grumezescu, V.; Balaure, P.C.; Chifiriuc, C.M. Water dispersible cross-linked magnetic chitosan beads for increasing the antimicrobial efficiency of aminoglycoside antibiotics. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 454, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philosof-Mazor, L.; Dakwar, G.R.; Popov, M.; Kolusheva, S.; Shames, A.; Linder, C.; Greenberg, S.; Heldman, E.; Stepensky, D.; Jelinek, R. Bolaamphiphilic vesicles encapsulating iron oxide nanoparticles: New vehicles for magnetically targeted drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 450, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladj, R.; Bitar, A.; Eissa, M.M.; Fessi, H.; Mugnier, Y.; le Dantec, R.; Elaissari, A. Polymer encapsulation of inorganic nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 458, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Andronescu, E.; Ficai, A.; Bleotu, C.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro assessment of the magnetic chitosan–carboxymethylcellulose biocomposite interactions with the prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 436, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chifiriuc, M.C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Saviuc, C.; Croitoru, C.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Lazar, V. Improved antibacterial activity of cephalosporins loaded in magnetic chitosan microspheres. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 436, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiangn, R.; Liu, T.; Lv, H.; Zhang, X. Single-microemulsion-based solvothermal synthesis of magnetite microflowers. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 4791–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wu, Y.; He, B.; Zeng, X.; Lai, K.; Gu, Z. Effect of sodium oleate as a buffer on the synthesis of superparamagnetic magnetite colloids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 347, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, G.; Grumezescu, V.; Andronescu, E.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Ficai, A.; Ghitulica, C.D.; Gheorghe, I.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Caprolactam-silica network, a strong potentiator of the antimicrobial activity of kanamycin against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 446, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y. A novel preparation of surface-modified paramagnetic magnetite/polystyrene nanocomposite microspheres by radiation-induced miniemulsion polymerization. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 327, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Andronescu, E.; Ficai, A.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Vasile, B.S.; Bleotu, C. Syntehsis, characterization and biological evaluation of Fe3O4/C12 core/shell nanosystem. Lett. Appl. NanoBioSci. 2012, 1, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu, A.M.; Saviuc, C.; Chifiriuc, C.M.; Hristu, R.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Balaure, P.; Stanciu, G.; Lazar, V. Inhibitory activity of Fe3O4/oleic acid/usnic acid—core/shell/extra-shell nanofluid on S. aureus biofilm development. IEEE Trans. NanoBioSci. 2011, 10, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishan, A. Rapid flow cytofluorometric analysis of mammalian cell cycle by propidium iodide staining. J. Cell Biol. 1975, 66, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogoşanu, G.D.; Popescu, F.C.; Busuioc, C.J.; Pârvănescu, H.; Lascăr, I. Natural products locally modulators of the cellular response: Therapeutic perspectives in skin burns. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2012, 53, 249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Mogoşanu, G.D.; Popescu, F.C.; Busuioc, C.J.; Lascăr, I.; Mogoantă, L. Comparative study of microvascular density in experimental third-degree skin burns treated with topical preparations containing herbal extracts. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2013, 54, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Saviuc, C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Bleotu, C.; Stanciu, G.; Hristu, R.; Mihaiescu, D.; Lazăr, V. In vitro methods for the study of microbial biofilms. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2011, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the nanostructures are available from the authors.

© 2014 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Grumezescu, A.M.; Gestal, M.C.; Holban, A.M.; Grumezescu, V.; Vasile, B.Ș.; Mogoantă, L.; Iordache, F.; Bleotu, C.; Mogoșanu, G.D. Biocompatible Fe3O4 Increases the Efficacy of Amoxicillin Delivery against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Molecules 2014, 19, 5013-5027. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19045013

Grumezescu AM, Gestal MC, Holban AM, Grumezescu V, Vasile BȘ, Mogoantă L, Iordache F, Bleotu C, Mogoșanu GD. Biocompatible Fe3O4 Increases the Efficacy of Amoxicillin Delivery against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Molecules. 2014; 19(4):5013-5027. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19045013

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrumezescu, Alexandru Mihai, Monica Cartelle Gestal, Alina Maria Holban, Valentina Grumezescu, Bogdan Ștefan Vasile, Laurențiu Mogoantă, Florin Iordache, Coralia Bleotu, and George Dan Mogoșanu. 2014. "Biocompatible Fe3O4 Increases the Efficacy of Amoxicillin Delivery against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria" Molecules 19, no. 4: 5013-5027. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19045013