Impact of Fermentation on the Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Whole Cereal Grains: A Mini Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Phenolic Compounds in WG Foods

3. Fermentation of WG Foods

4. Impact of Fermentation on Phenolic Compounds in WGs

5. Impact of Fermentation on Antioxidant Activity in WGs

6. Future Perspective

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arai, S. Studies on functional foods in Japan-state of the art. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1996, 60, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hallfrisch, J.; Scholfield, D.J.; Behall, K.M. Blood pressure reduced by whole grain diet containing barley or whole wheat and brown rice in moderately hypercholesterolemic men. Nutr. Res. 2003, 23, 1631–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntunen, K.S.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Poutanen, K.S.; Niskanen, L.K.; Mykkanen, H.M. High-fiber rye bread and insulin secretion and sensitivity in healthy postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Behall, K.M.; Scholfield, D.J.; Hallfrisch, J. Diets containing barley significantly reduce lipids in mildly hypercholesterolemic men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behall, K.M.; Scholfield, D.J.; Hallfrisch, J. Whole-grain diets reduce blood pressure in mildly hypercholesterolemic men and women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1445–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquart, L.; Jones, J.M.; Chohen, E.A.; Poutanen, K. The future of whole grains. In Whole Grains and Health; Marquart, L., Jacobs, D.R., McIntosh, G.H., Poutanen, K., Reicks, M., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Ames, IA, USA, 2007; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Priebe, M.G.; van Binsbergen, J.J.; de Vos, R.; Vonk, R.J. Whole grain foods for the prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 23, CD006061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maki, K.C.; Beiseigel, J.M.; Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Gugger, C.K.; Reeves, M.S.; Farmer, M.V.; Kaden, V.N.; Rains, T.M. Whole-grain ready-to-eat oat cereal, as part of a dietary program for weight loss, reduces low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in adults with overweight and obesity more than a dietary program including low-fiber control foods. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, P.; Duthie, G.; Vaughan, N.; Brittenden, J.; Simpson, W.G.; Duthie, S.; Mutch, W.; Wahle, K.; Horgan, G.; Thies, F. Effect of increased consumption of whole-grain foods on blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk markers in healthy middle-aged persons: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.B.; Bruce, S.J.; Blondel-Lubrano, A.; Oguey-Araymon, S.; Beaumont, M.; Bourgeois, A.; Nielsen-Moennoz, C.; Vigo, M.; Fay, L.B.; Kochhar, S.; et al. A whole-grain cereal-rich diet increases plasma betaine and tends to decrease total and LDL-cholesterol compared with a refined-grain diet in healthy subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 1492–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seal, C.J.; Brownlee, I.A. Whole-grain foods and chronic disease: Evidence from epidemiological and intervention studies. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AACC. Definition of Whole Grain. Available online: https://www.cerealsgrains.org/initiatives/definitions/Pages/WholeGrain.aspx (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Harnack, L.; Liu, R.H.; McKeown, N.; Seal, C.; Liu, S.; Fahey, G.C. Putting the whole grain puzzle together: Health benefits associated with whole grains-Summary of American Society for Nutrition 2010 satellite symposium. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1011S–1022S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borneo, R.; León, A.E. Whole grain cereals: Functional components and health benefits. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRae, M.P. Health benefits of dietary whole grains: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. J. Chiroprac. Med. 2017, 16, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Călinoiu, L.F.; Vodnar, D.C. Whole grains and phenolic acids: A review on bioactivity, functionality, health benefits and bioavailability. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

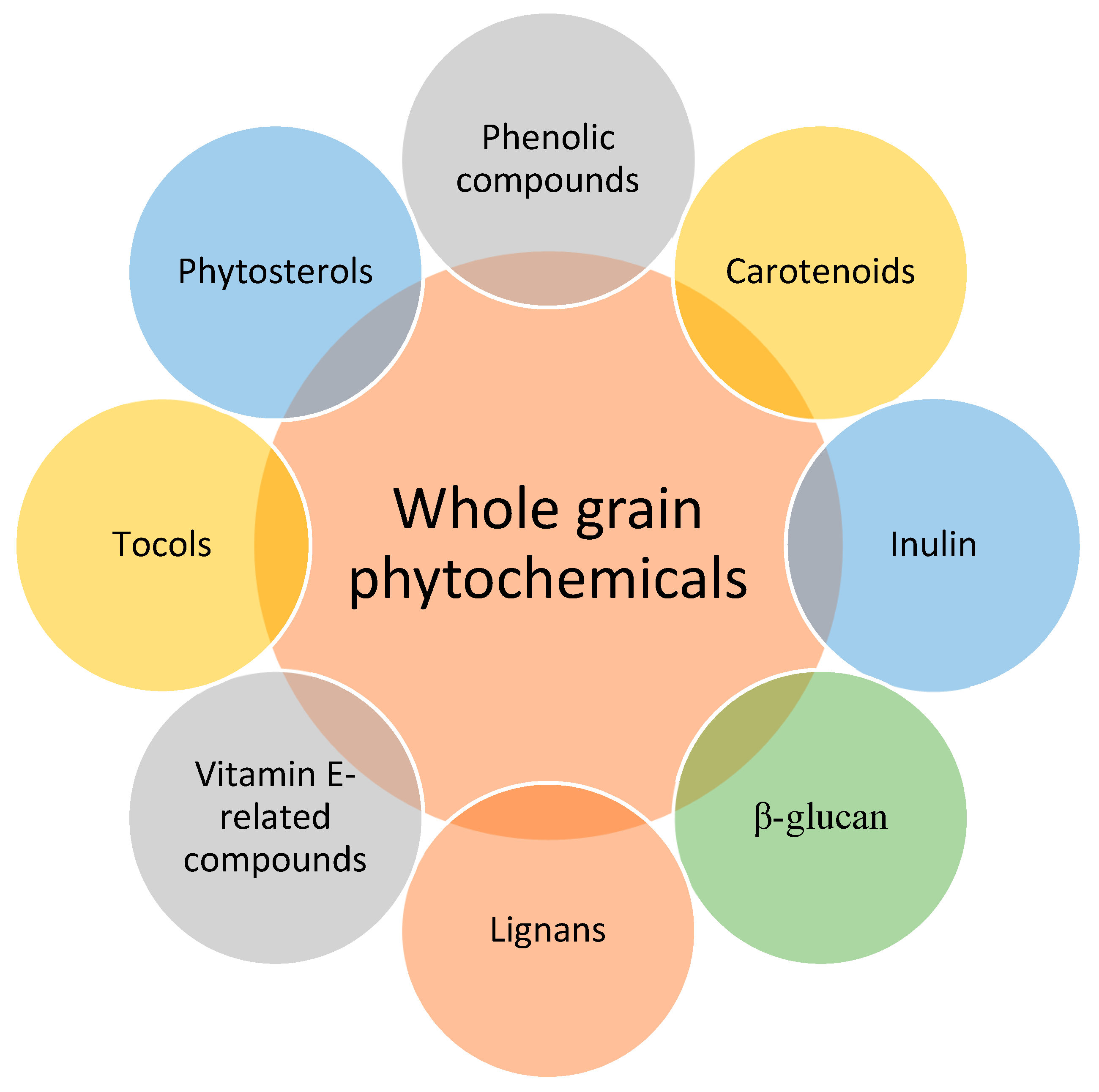

- Liu, R.H. Whole grain phytochemicals and health. J. Cereal. Sci. 2007, 46, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okarter, N.; Liu, R.H. Health benefits of whole grain phytochemicals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 50, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sang, S. Phytochemicals in whole grain wheat and their health-promoting effects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koistinen, V.M.; Katina, K.; Nordlund, E.; Poutanen, K.; Hanhineva, K. Changes in the phytochemical profile of rye bran induced by enzymatic bioprocessing and sourdough fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idehen, E.; Tang, Y.; Sang, S. Bioactive phytochemicals in barley. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harvard Health Letter. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts. I. Whole grain. Harv. Health Lett. 1999, 25, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer-Lequart, C.; Lehmann, U.; Ross, A.B.; Roger, O.; Eldridge, A.L.; Ananta, E.; Bietry, M.F.; King, L.R.; Moroni, A.V.; Srichuwong, S.; et al. Whole grain in manufactured foods: Current use, challenges and the way forward. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1562–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.M.; Reicks, M.; Adams, J.; Fulcher, G.; Weaver, G.; Kanter, M.; Marquart, L. The importance of promoting a whole grain foods message. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2002, 21, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellen, P.B.; Walsh, T.F.; Herrington, D.M. Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2008, 18, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, E.Q.; Chacko, S.A.; Chou, E.L.; Kugizaki, M.; Liu, S. Greater whole-grain intake is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and weight gain. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaillzadeh, A.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F. Whole-grain consumption and the metabolic syndrome: A favorable association in Tehranian adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, D.; Marquart, L.; Slavin, J.; Kushi, L.H. Whole grain intake and cancer: An expanded review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Cancer 1998, 30, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourouti, N.; Papavagelis, C.; Plytzanopoulou, P.; Kontogianni, M.; Vassilakou, T.; Malamos, N.; Linos, A.; Panagiotakos, D. Dietary patterns and breast cancer: A case-control study in women. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, S.M.; Maydani, M.; Barnett, J.B.; Goldin, B.; Kane, A.; Rasmussen, H.; Brown, C.; Vangay, P.; Knights, D.; Jonnalagadda, S.; et al. Substituting whole grains for refined grains in a 6-wk randomized trial has a modest effect on gut microbiota and immune and inflammatory markers of healthy adults. Am. J. Clin Nutr. 2017, 105, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boudet, A.M. Evolution and current status of research in phenolic compounds. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2722–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, E.K.; Moroni, A.; Zannini, E. Medical nutrition therapy: Use of sourdough lactic acid bacteria as a cell factory for delivering functional biomolecules and food ingredients in gluten free bread. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10, S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coda, R.; Cagno, R.D.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Sourdough lactic acid bacteria: Exploration of non-wheat cereal-base fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2014, 37, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Adeboye, A.S.; Adebiyi, J.A.; Sobowale, S.S.; Ogundele, O.M.; Kayitesi, E. Advances in fermentation technology for novel food products. In Innovations in Technologies for Fermented Food and Beverage Industries; Panda, S.K., Shetty, P.H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Adebo, O.A.; Kayitesi, E.; Tugizimana, F.; Njobeh, P.B. Differential metabolic signatures in naturally and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermented ting (a Southern African food) with different tannin content, as revealed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC–MS)-based metabolomics. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebiyi, J.A.; Kayitesi, E.; Adebo, O.A.; Changwa, R.; Njobeh, P.B. Food fermentation and mycotoxin detoxification: An African perspective. Food Cont. 2019, 106, 106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robards, K.; Prenzler, P.D.; Tucker, G.; Swatsitang, P.; Glover, W. Phenolic compounds and their role in oxidative process in fruits. Food Chem. 1999, 66, 401–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadidi, F. Phytochemicals in oilseeds. In Phytochemicals in Nutrition and Health; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Randhir, R.; Lin, Y.-T.; Shetty, K. Phenolics, their antioxidant and antimicrobial activity in dark germinated fenugreek sprouts in response to peptide and phytochemical elicitors. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 13, 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of grain legume seeds: A review. Food Res. Int. 2017, 101, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awika, J.M.; Rooney, L.W. Sorghum phytochemicals and their potential impact on human health. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 1199–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D. Tannins from foods to combat diseases. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Rev. 2015, 4, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Adebo, O.A. Metabolomics, Physicochemical Properties and Mycotoxin Reduction of Whole Grain ting (a Southern African Fermented Food) Produced via Natural and Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Fermentation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa, October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, G.; Puniya, A.K.; Aguliar, C.N.; Singh, K. Interaction of gut microflora with tannins in feeds. Naturwissenschaften 2005, 92, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, M.N. Chlorogenic acids and other cinnamates-nature, occurrence, and dietary burden. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1999, 79, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondia-Pons, I.; Aura, A.M.; Vuorela, S.; Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkanen, H.; Poutanen, K. Rye phenolics in nutrition and health. J. Cereal Sci. 2009, 49, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadidi, F.; Chandrasekara, A. Millet grain phenolics and their role in disease risk reduction and health promotion: A review. J. Funct. Food 2013, 5, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadidi, F.; Yeo, J. Insoluble-bound phenolics in food. Molecules 2016, 21, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Cao, W.; Chi, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, B. Whole cereal grains and potential health effects: Involvement of the gut microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2018, 103, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Goel, N. Phenolic acids: Natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 24, e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masebe, K.M.; Adebo, O.A. Production and quality characteristics of a probiotic beverage from watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). In Engineering, Technology and Waste Management (SETWM-19), Proceedings of the 17th Johannesburg International Conference on Science, Johannesburg, South Africa, 18–19 November 2019; Fosso-Kankeu, E., Waanders, F., Bulsara, H.K.P., Eds.; Eminent Association of Pioneers and North-West University: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; pp. 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, A.J.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P.; Cotter, P.D. Fermented beverages with health-promoting potential: Past and future perspectives. Trend Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 38, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Adebiyi, J.A.; Gbashi, S.; Phoku, J.Z.; Kayitesi, E. Fermented pulse-based foods in developing nations as sources of functional foods. In Functional Food-Improve Health through Adequate Food; Hueda, M.C., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017; pp. 77–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik, G.; Satya, S.; Naik, S.N. Food processing a tool to pesticide residue dissipation—A review. Food Rev. Int. 2009, 42, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebiyi, J.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Kayitesi, E. Assessment of nutritional and phytochemical quality of Dawadawa (an African fermented condiment) produced from Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea). Microchem. J. 2019, 149, 104034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopart, E.E.; Drago, S.R.; De Greef, D.M.; Torres, R.L.; Gonzalez, A.R. Effects of extrusion conditions on physical and nutritional properties of extruded whole grain red sorghum (Sorghum spp.). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, L.S.; Variyam, J.N.; Allshouse, J.E.; Putnam, J.J.; Lin, B.H. Choose a variety of grains daily, especially whole grains: A challenge for consumers. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 473S–486S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kyrø, C.; Skeie, G.; Dragsted, L.O.; Christensen, J.; Overvad, K.; Hallmans, G.; Johansson, I.; Lund, E.; Slimani, N.; Johnsen, J.F.; et al. Intake of whole grain in Scandinavia: Intake, sources and compliance with new national recommendations. Scand J. Public Health 2012, 40, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund-Jonsson, C.; Sanderg, A.S.; Alminger, M.L. Reduction of phytate content while preserving minerals during whole grain cereal tempe fermentation. J. Cereal Sci. 2006, 44, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyarekua, M.A. Effect of co-fermentation on nutritive quality and pasting properties of maize/cowpea/sweet potato as complementary food. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2013, 13, 7171–7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obinna-Echem, P.C.; Beal, P.; Kuri, V. Effect of processing method on the mineral content of Nigerian fermented maize infant complementary food-akamu. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 61, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salar, R.J.; Purewal, S.S.; Bhatti, M.S. Optimization of extraction conditions and enhancement of phenolic content and antioxidant activity of pearl millet fermented with Aspergillus awamori MTCC-54. Resour. Effic. Technol. 2016, 2, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, E.; White, J.; Seney, S.; Hekmat, S.; McDowell, T.; Sumarah, M.; Reid, G. A novel millet-based probiotic fermented food for the developing world. Nutrients 2017, 9, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheela, P.; UmaMaheswari, T.; Kanchana, S.; Kamalasundari, S.; Hemalatha, G. Development and evaluation of fermented millet milk based curd. J. Pharmacog. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 714–717. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Compaoré-Sérémé, D.; Sawadogo-Lingani, H.; Coda, R.; Katina, K.; Maina, N.J. Influence of dextran synthesized in situ on the rheological, technological and nutritional properties of whole grain pearl millet bread. Food Chem. 2019, 285, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Rui, X.; Li, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Dong, M. Whole-grain oats (Avena sativa L.) as a carrier of lactic acid bacteria and a supplement rich in angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides through solid-state fermentation. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 2270–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamel, T.H.; Abdel-Aal, E.M.; Tosh, S.M. Effect of yeast-fermented and sour-dough making processes on physicochemical characteristics of β-glucan in whole wheat/oat bread. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannini, E.; Jeske, S.; Lynch, K.M.; Arendt, E.K. Development of novel quinoa-based yoghurt fermented with dextran producer Weissella cibaria MG1. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 268, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, M.; Johnson, S.K.; Liu, S.Q.; Al-Mheiri, A.; Abushelaibi, A. Cytotoxicity, antihypertensive, antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of solid-state fermented lupin, quinoa and wheat by Bifidobacterium species: In vitro investigations. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 95, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddrick, O.; Jones, O.A.H.; Cornell, H.J.; Small, D.M. The influence of fermentation processes and cereal grains in wholegrain bread on reducing phytate content. J. Cereal Sci. 2014, 59, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koistinen, V.M.; Mattila, O.; Katina, K.; Poutanen, K.; Aura, A.M.; Hanhineva, K. Metabolic profiling of sourdough fermented wheat and rye bread. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, D.P.; Lee, I.; Risérus, U.; Langton, M.; Landberg, R. Effects of unfermented and fermented whole grain rye crisp breads served as part of a standardized breakfast, on appetite and postprandial glucose and insulin responses: A randomized cross-over trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raninen, K.; Lappi, J.; Kolehmainen, M.; Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkanen, H.; Poutanen, K.; Raatikainen, O. Diet-derived changes by sourdough-fermented rye bread in exhaled breath aspiration ion mobility spectrometry profiles in individuals with mild gastrointestinal symptoms. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 8, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Shi, L.; Webb, D.L.; Hellström, P.M.; Risérus, U.; Landberg, R. Effects of whole-grain rye porridge with added inulin and wheat gluten on appetite, gut fermentation and postprandial glucose metabolism: A randomised, cross-over, breakfast study. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 116, 2139–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beckmann, M.; Lloyd, A.J.; Haldar, S.; Seal, C.; Brandt, K.; Draper, J. Hydroxylated phenylacetamides derived from bioactive benzoxazinoids are bioavailable in humans after habitual consumption of whole grain sourdough rye bread. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 1859–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zamaratskaia, G.; Johansson, D.P.; Junqueira, M.A.; Deissler, L.; Langton, M.; Hellstrom, P.M.; Landberg, R. Impact of sourdough fermentation on appetite and postprandial metabolic responses—A randomised cross-over trial with whole grain rye crispbread. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikediobi, C.O.; Olugboji, O.; Okoh, P.N. Cyanide profile of component parts of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) sprouts. Food Chem. 1988, 27, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaee, S.; Abdel-Aal, E.M. Pasting properties of starch and protein in selected cereals and quality of their food products. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, N.R.; Taylor, J.R.N.; Rooney, L.W. The effect of sorghum type and processing on the antioxidant properties of African sorghum-based foods. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 1412–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Taylor, J.R.N. Protein biofortified sorghum: Effect of processing into traditional African foods on their protein quality. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2386–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akingbala, J.O.; Rooney, L.W.; Fauboin, J.M. Physical, chemical, and sensory evaluation of ogi from sorghum of differing kernel characteristics. J. Food Sci. 1981, 76, 1532–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukuru, S.Z.; Butler, L.G.; Rogler, J.C.; Kirleis, A.W.; Ejeta, G.; Axtell, J.D.; Mertz, E.T. Traditional processing of high-tannin sorghum grain in Uganda and its effect on tannin, protein digestibility, and rat growth. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992, 40, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, J.; Taylor, J.R.N.; Oelofse, A. Effects of reducing phytate content in sorghum through genetic modification and fermentation on in vitro iron availability in whole grain porridges. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Adebiyi, J.A.; Kayitesi, E. Co-influence of fermentation time and temperature on physicochemical properties, bioactive components and microstructure of ting (a Southern African food) from whole grain sorghum. Food Biosci. 2018, 25, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Kayitesi, E. Fermentation by Lactobacillus fermentum strains (singly and in combination) enhances the properties of ting from two whole grain sorghum types. J. Cereal Sci. 2018, 82, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamene, A.; Kariluoto, S.; Baye, K.; Humblot, C. Quantification of folate in the main steps of traditional processing of tef injera, a cereal based fermented staple food. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 87, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotcheva, V.; Pandiella, S.S.; Angelov, A.; Roshkova, Z.; Webb, C. Monitoring the fermentation of the traditional Bulgarian beverage boza. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 36, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, K.D.; Adem, E. Comparison of autoclave, microwave, IR and UV-stabilization of whole wheat flour branny fractions upon the nutritional properties of whole wheat bread. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Struyf, N.; Laurent, J.; Verspreet, J.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Coutrin, C.M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces marxianus cocultures allow reduction of fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols levels in whole wheat bread. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8704–8713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- García-Mantrana, I.; Yebra, M.J.; Haros, M.; Monedero, V. Expression of bifidobacterial phytases in Lactobacillus casei and their application in a food model of whole-grain sourdough bread. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 216, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dey, T.B.; Kuhad, R.C. Enhanced production and extraction of phenolic compounds from wheat by solid-state fermentation with Rhizopus oryzae RCK2012. Biotechnol. Rep. 2014, 4, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Starzyńska-Janiszewska, A.; Stodolak, B.; Socha, R.; Mickowska, B.; Wywrocka-Gurgul, A. Spelt wheat tempe as a value-added whole-grain food product. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 113, 108250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuobariene, L.; Cizeikiene, D.; Gradzeviciute, E.; Hansen, A.S.; Rasmussen, S.K.; Juodeikiene, G.; Vogensen, F.K. Phytase-active lactic acid bacteria from sourdoughs: Isolation and identification. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Mulaba-Bafubiandi, A.F.; Adebiyi, J.A.; Desobgo, Z.S.C.; Kayitesi, E. Optimization of fermentation conditions for ting production using response surface methodology. J. Food Proc. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salar, R.K.; Certik, M.; Brezova, V. Modulation of phenolic content and antioxidant activity of maize by solid state fermentation with Thamnidium elegans CCF 1456. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2012, 17, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hole, A.S.; Rud, I.; Grimmer, S.; Sigl, S.; Narvhus, J.; Sahlstrøm, S. Improved bioavailability of dietary phenolic acids in whole grain barley and oat groat following fermentation with probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus johnsonii, and Lactobacillus reuteri. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 6369–6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liukkonen, K.H.; Katina, K.; Wilhelmsson, A.; Myllymaki, O.; Lampi, A.M.; Kariluoto, S.; Piironen, V.; Heinonen, S.M.; Nurmi, T.; Adlercreutz, H.; et al. Process-induced changes on bioactive compounds in whole grain rye. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, K.; Liukkonen, K.H.; Kaukovirta-Norja, A.; Adlercreutz, H.; Heinonen, S.M.; Lampi, A.M.; Pihlava, J.M.; Poutanen, K. Fermentation-induced changes in the nutritional value of native or germinated rye. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 46, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrajda-Brdak, M.; Konopka, I.; Tańska, M.; Czaplicki, S. Changes in the content of free phenolic acids and antioxidative capacity of wholemeal bread in relation to cereal species and fermentation type. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 2247–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohapatra, D.; Patel, A.S.; Kar, A.; Deshpande, S.S.; Tripathi, M.K. Effect of different processing conditions on proximate composition, anti-oxidants, anti-nutrients and amino acid profile of grain sorghum. Food Chem. 2019, 271, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ðordevic, T.M.; Šiler-Marinkovic, S.S.; Dimitrijevic-Brankovic, S.I. Effect of fermentation on antioxidant properties of some cereals and pseudo cereals. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripari, V.; Bai, Y.; Gänzle, M.G. Metabolism of phenolic acids in whole wheat and rye malt sourdoughs. Food Microbiol. 2019, 77, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.B.; Kuhad, R.C. Upgrading the antioxidant potential of cereals by their fungal fermentation under solid-state cultivation conditions. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 59, 493–499. [Google Scholar]

- Gänzle, M.G. Enzymatic and bacterial conversions during sourdough fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2014, 37, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, K.; Juvonen, R.; Laitila, A.; Flander, L.; Nordlund, E.; Kariluoto, S.; Piironen, V.; Poutanen, K. Fermented wheat bran as a functional ingredient in baking. Cereal Chem. 2012, 89, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerny, M.; Schieberie, P. Important aroma compounds in freshly ground whole meal and white wheat flour-identification and quantitative changes during sourdough fermentation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6835–6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, H.; Curiel, J.A.; Landete, J.M.; de las Rivas, B.; de Felipe, F.L.; Gomez-Cordoves, C.; Mancheno, J.M.; Munoz, R. Food phenolics and lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 132, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Svensson, L.; Sekwati-Monang, B.; Lutz, D.L.; Schieber, A.; Gänzle, M.G. Phenolic acids and flavonoids in nonfermented and fermented red sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 9214–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Maldonado, A.F.; Schieber, A.; Gänzle, M.G. Structure-function relationships of the antibacterial activity of phenolic acids and their metabolism by lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 111, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raccach, M. The antimicrobial activity of phenolic antioxidant in food: A review. J. Food Saf. 1984, 6, 141–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filannino, P.; Bai, Y.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Gänzle, M.G. Metabolism of phenolic compounds by Lactobacillus spp. during fermentation of cherry juice and broccoli puree. Food Microbiol. 2015, 46, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaur, G.; Oh, J.H.; Filannino, P.; Gobbetti, M.; van Pijkeren, J.P.; Gänzle, M.G. Genetic determinants of hydroxycinnamic acid metabolism in heterofermentative lactobacilli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurutas, E.B. The importance of antioxidants which play the role in cellular response against oxidative/nitrosative stress: Current state. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Slavin, J. Why whole grains are protective: Biological mechanisms. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, B.; Hucl, P.; Chibbar, R.N. Phenolic content and antioxidant properties of bran in 51 wheat cultivars. Cereal Chem. 2008, 85, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevgi, K.; Tepe, B.; Sarikurkcu, C. Antioxidant and DNA damage protection potentials of selected phenolic acids. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 77, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattenberg, L.W. Chemoprevention of cancer. Cancer Res. 1985, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J.L. Mechanisms for the impact of whole grain foods on cancer risk. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000, 19, 300S–307S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Ghasemzadeh, N. Flavonoids and phenolic acids: Role and biochemical activity in plants and human. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 6697–6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juurlink, B.H.J.; Azouz, H.J.; Aldalati, A.M.Z.; AlTinawi, B.M.H.; Ganguly, P. Hydroxybenzoic acid isomers and the cardiovascular system. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beta, T.; Nam, S.; Dexter, J.E.; Sapirstein, H.D. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of pearled wheat and roller-mill fractions. Cereal Chem. 2005, 82, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Tsao, R.; Yang, R.; Cui, S.W. Phenolic acid profiles and antioxidant activities of wheat bran extracts and the effect of hydrolysis conditions. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shewry, P.R.; Ward, J.L. Phenolic acids in wheat varieties in the HEALTHGRAIN diversity screen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9732–9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.; Khan, M.R.; Sahreen, S.; Ahmed, M. Evaluation of phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of various solvent extracts of Sonchus asper (L.) Hill. Chem. Central J. 2012, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, T.; Ho, C.T. Antioxidant activities of buckwheat extracts. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žilić, S.; Serpen, A.; Akıllıoğlu, G.; Janković, M.; Gökmen, V. Distributions of phenolic compounds, yellow pigments and oxidative enzymes in wheat grains and their relation to antioxidant capacity of bran and debranned flour. J. Cereal Sci. 2012, 56, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, S.; Primiterra, M.; Tagliamonte, M.C.; Carnevali, A.; Gianotti, A.; Bordoni, A.; Canestrari, F. Counteraction of oxidative damage in the rat liver by an ancient grain (Kamut brand khorasan wheat). Nutrition 2012, 28, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.N.; Bristi, N.J.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verni, M.; Verardo, V.; Rizzello, C.G. How fermentation affects the antioxidant properties of cereals and legumes. Foods 2019, 8, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gianotti, A.; Danesi, F.; Verardo, V.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Valli, V.; Russo, A.; Riciputi, Y.; Tossani, N.; Caboni, M.F.; Guerzoni, M.E.; et al. Role of whole grain in the in vivo protection from oxidative stress. Front. Biosci. 2011, 16, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moore, J.; Cheng, Z.; Hao, J.; Guo, G.; Liu, J.G.; Lin, C.; Yu, L.L. Effects of solid state yeast treatment on the antioxidant properties and protein and fiber compositions of common hard wheat bran. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10173–10182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combest, S.; Warren, C. Perceptions of college students in consuming whole grain foods made with brewers’ spent grain. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 7, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuznesof, S.; Brownlee, I.A.; Moore, C.; Richardson, D.P.; Jebb, S.A.; Seal, C.J. WHOLEheart study participant acceptance of wholegrain foods. Appetite 2012, 59, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, M.; Evans, C.; Hugh-Jones, S. Factors influencing adolescent whole grain intake: A theory-based qualitative study. Appetite 2016, 101, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chea, M.; Mobley, A.R. Factors associated with identification and consumption of whole-grain foods in a low-income population. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Whole Grain(s) | Food | Type of Fermentation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barley and oat | Tempe | SSF | Eklund-Jonsson et al. [59] |

| Maize | Akamu/Ogi | SSF | Oyarekua [60], Obinna-Echem et al. [61] |

| Millet | Koji | SSF | Salar et al. [62] |

| Millet | Probiotic drink | SmF | Di Stefano et al. [63] |

| Millet | Fermented milk | SmF | Sheela et al. [64] |

| Millet | Sourdough bread | SSF | Wang et al. [65] |

| Oat | Fermented oat | SSF | Wu et al. [66] |

| Oat, wheat | Bread | SSF | Gamel et al. [67] |

| Quinoa | Yoghurt | SmF | Zannini et al. [68] |

| Quinoa, wheat | Fermented product | SSF | Ayyash et al. [69] |

| Rye, oat, wheat | Bread | SSF | Buddrick et al. [70] |

| Rye, wheat | Sourdough bread | SSF | Koistinen et al. [71] |

| Rye | Bread | SSF | Johansson et al. [72], Raninen et al. [73] |

| Rye | Porridge | SSF | Lee et al. [74] |

| Rye | Sourdough bread | SSF | Beckmann et al. [75], Zamaratskaia et al. [76] |

| Sorghum | Burukutu | SmF | Ikediobi et al. [77] |

| Sorghum | Fermented balls | SSF | Ragaee and Abdel-Aal [78] |

| Sorghum | Fermented porridge | SSF | Dlamini et al. [79] |

| Sorghum | Injera | SSF | Taylor and Taylor [80] |

| Sorghum | Ogi | SmF | Akingbala et al. [81] |

| Sorghum | Omuramba | SmF | Mukuru et al. [82] |

| Sorghum | Ting | SSF | Kruger et al. [83], Adebo et al. [84,85] |

| Sorghum | Uji | SmF | Taylor and Taylor [80] |

| Tef | Injera | SSF | Tamene et al. [86] |

| Wheat | Boza | SmF | Gotcheva et al. [87] |

| Wheat | Bread | SSF | Mustafa and Adem [88], Struyf et al. [89] |

| Wheat | Sourdough bread | SSF | García-Mantrana et al. [90] |

| Wheat | Tempe | SSF | Dey and Kuhad [91], Starzyńska-Janiszewska et al. [92] |

| Whole Grain | Fermented Product | Phenolics Investigated | Analytical Method | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barley and oat groat | Fermented product | Free and bound PAs | Colorimetric; HPLC | Increase in total content of bound PAs in flours from WG-barley related to increased content of bound p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, and dimers of ferulic acid (5,5′- diferulic, 8-o-4-diferulic, and 8,5′-diferulic acids). | Hole et al. [96] |

| Maize | Fermented product | TPC | Colorimetric | Increase in TPC after fermentation attributed to the activities of β-glucosidase, capable of hydrolyzing phenolic phucosides to release free phenolics | Salar et al. [95] |

| Millet | Koji | TPC | Colorimetric | Increase in TPC of fermented product due to mobilization of PCs from their bound form to a free state through enzymes produced during fermentation | Salar et al. [62] |

| Millet | Sourdough bread | TPC | Colorimetric | Increase and decrease in soluble and bound phenolic content. Slight decrease in TPC observed. Increment of soluble phenolic content may be due to acidification, production of hydrolytic enzymes by LAB, and/or activation of indigenous cereal enzymes, which broke down the bran cell wall structure | Wang et al. [65] |

| Quinoa, wheat | Fermented product | TPC | Colorimetric | Increase in TPC may be attributed to hydrolytic activities (e.g., esterases) of Bifidobacteria strains that released more PCs via the hydrolysis of complexed forms, possibly the synthesis of new bioactive compounds detected as PCs | Ayyash et al. [69] |

| Rye | Baked sourdough | TPC, PAs | Colorimetric, HPLC | Fermentation phase more than doubled the levels of easily extractable PCs | Liukkonen et al. [97] |

| Rye | Sourdough | TPC, PAs | Colorimetric, HPLC | Increased level of total PCs due to increases in methanol-extractable PCs. Modification in levels of bioactive compounds during fermentation by the metabolic activity of microbes. Fermentation-induced structural breakdown of cereal cell walls might have also occurred and led to liberation and/or synthesis of various bioactive compounds | Katina et al. [98] |

| Rye, wheat | Whole meal bread | PAs | HPLC | Increase in PAs due to activities of phenolic acid esterases during the fermentation stage | Skrajda-Brdak et al. [99] |

| Sorghum | Fermented porridge | TPC, TNC | Colorimetric | Reduction in TNC and TPC. Reduction in TNC could be due to binding of tannins with protein and other components, which reduces their extractability and tannin degradation by microbial enzymes | Dlamini et al. [79] |

| Sorghum | Fermented product | TPC, TNC | Colorimetric | Increase in TPC, decrease in TNC | Mohapatra et al. [100] |

| Sorghum | Ting | Flavonoids, PA, TFC, TNC, TPC | Colorimetric, LC-MS/MS | Decrease in TFC, TNC, and TPC attributed to possible degradation of PCs and hydrolysis of bioactive compounds. Breakdown of tannin-related compounds to lower molecular weight compounds, which affected extractability. Increase in PA and flavonoids could be due to decarboxylation, hydrolysis, microbial oxidation, and reduction as well as esterification reactions that occurred during fermentation | Adebo et al. [84,85] |

| Wheat | Fermented product | TPC | Colorimetric | Increase in TPC through modification in levels of bioactive compounds during fermentation by the metabolic activity of microbes | Ðordevic et al. [101] |

| Wheat | Sourdough | PAs | LC-MS/MS, UPLC | Degradation, reduction of some PAs and content of some remain unchanged. Release of PAs from bound fraction, metabolism of PA by LAB strains and action of enzymes (decarboxylases, esterases, and reductases) | Ripari et al. [102] |

| Wheat | Tempe | TPC, PCs | Colorimetric, TLC, UPLC | Increase in TPC after fermentation, possibly due to release of bound compounds from the wheat matrix | Dey and Kuhad [91] |

| Wheat | Tempe | Free and condensed PAs | HPLC | Increase in the sum of PA could be linked to an increase in their extractability after fermentation | Starzyńska-Janiszewska et al. [92] |

| Wheat, brown rice, maize, oat | Fermented product | TPC, PAs | Colorimetric, HPLC | TPC of all fermented samples increased except for Rhizopus oligosporus fermented maize. Increase as well as decrease in PA levels. Decreases was attributed to strain/specie specificity and/or grain composition. General increases were alluded to enhanced bioavailability of cereal phenolics. | Dey and Kuhad [103] |

| Whole Grain | Fermented Product | Assay | Mechanism(s) Reported | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maize | Fermented product | ABTS, DPPH | Increase in ABTS and DPPH due to the role of the hydrolytic enzyme that released/mobilized bound polyphenolic compounds, which enhanced AAs. | Salar et al. [95] |

| Millet | Koji | ABTS, DPPH | Koji showed increased scavenging of ABTS and DPPH radicals due to the release of a bound form of phytochemicals present and high levels of TPC modulated during fermentation. | Salar et al. [62] |

| Millet | Sourdough bread | DPPH | Increase in DPPH radical inhibition after sourdough fermentation. The conversion of bound to soluble PCs improved the health-related functionality of the final products. | Wang et al. [65] |

| Quinoa, wheat | Fermented product | ABTS, DPPH | An increase in ABTS and DPPH values was attributed to the soluble phytochemicals released during fermentation and to bioactive peptides formed as a result of proteolytic activity. | Ayyash et al. [69] |

| Rye | Baked sourdough | DPPH | The fermentation stage increased AA likely due to an increased level of extractable PCs. | Liukkonen et al. [97] |

| Sorghum | Fermented porridge | ABTS, DPPH | Reduction in antioxidant levels after fermentation attributed to changes during processing that affected the extraction of total phenols and tannins. Such changes were hypothesized to have likely involved associations between the tannins, phenols, proteins, and other compounds in the grain. | Dlamini et al. [79] |

| Sorghum | Fermented product | CUPRAC, DPPH | Increase in AAs investigated. | Mohapatra et al. [100] |

| Sorghum | Ting | ABTS | Increase in AA due to regenerated and released bioactive compounds (including non-phenolic components after fermentation with the L. fermentum strains), which might have contributed to the radical scavenging properties of the product. | Adebo et al. [85] |

| Wheat | Fermented product | DPPH, FRAP, TBA | Increase in the investigated AAs. | Ðordevic et al. [101] |

| Wheat | Tempe | ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, HP-scavenging and OH-scavenging assays | Increase in antioxidant properties investigated attributed to the composition of PCs, unidentified compounds, and other water-soluble bioactive compounds like small peptides and xylo-oligosaccharides produced during fermentation. | Dey and Kuhad [91] |

| Wheat | Tempe | ABTS, OH-scavenging and FCRS-RP assays | Increase in soluble antioxidant potential as fermentation increased extractable antiradical activity scavenging potential, which might be due to the release of peptides and other compounds during fermentation. | Starzyńska-Janiszewska et al. [92] |

| Wheat, brown rice, maize, oat | Fermented product | ABTS, DPPH | Both ABTS and DPPH scavenging properties were enhanced after fermentation of the WG-cereals by all the four micro-organisms (except R. oligosporus-fermented maize). Increases related to release of more soluble bioactive compounds, such as peptides and oligosaccharides. | Dey and Kuhad [103] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adebo, O.A.; Gabriela Medina-Meza, I. Impact of Fermentation on the Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Whole Cereal Grains: A Mini Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25040927

Adebo OA, Gabriela Medina-Meza I. Impact of Fermentation on the Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Whole Cereal Grains: A Mini Review. Molecules. 2020; 25(4):927. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25040927

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdebo, Oluwafemi Ayodeji, and Ilce Gabriela Medina-Meza. 2020. "Impact of Fermentation on the Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Whole Cereal Grains: A Mini Review" Molecules 25, no. 4: 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25040927