Nanomaterials for Modulating the Aggregation of β-Amyloid Peptides

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Nanomaterials

2.1. Gold-Based Nanomaterials

2.2. Carbon

2.2.1. Graphene-Based Materials

2.2.2. Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)

2.2.3. Carbon Nanospheres

2.2.4. Fullerene

2.2.5. Carbon Dots

2.3. Metal-Oxide Nanomaterials

2.3.1. Magnetic Nanoparticle (MNPs)

2.3.2. Polyoxometalates (POMs)

2.3.3. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles (CNPs)

2.4. 2D Nanosheets

2.4.1. Black Phosphorus

2.4.2. Transition Metal Dichalcogenides

2.4.3. Graphitic Carbon Nitride

2.5. Metal-Organic Frameworks

2.6. Semiconductor Quantum Dots

2.7. Self-Assembled Nanomaterials

2.7.1. Liposomes

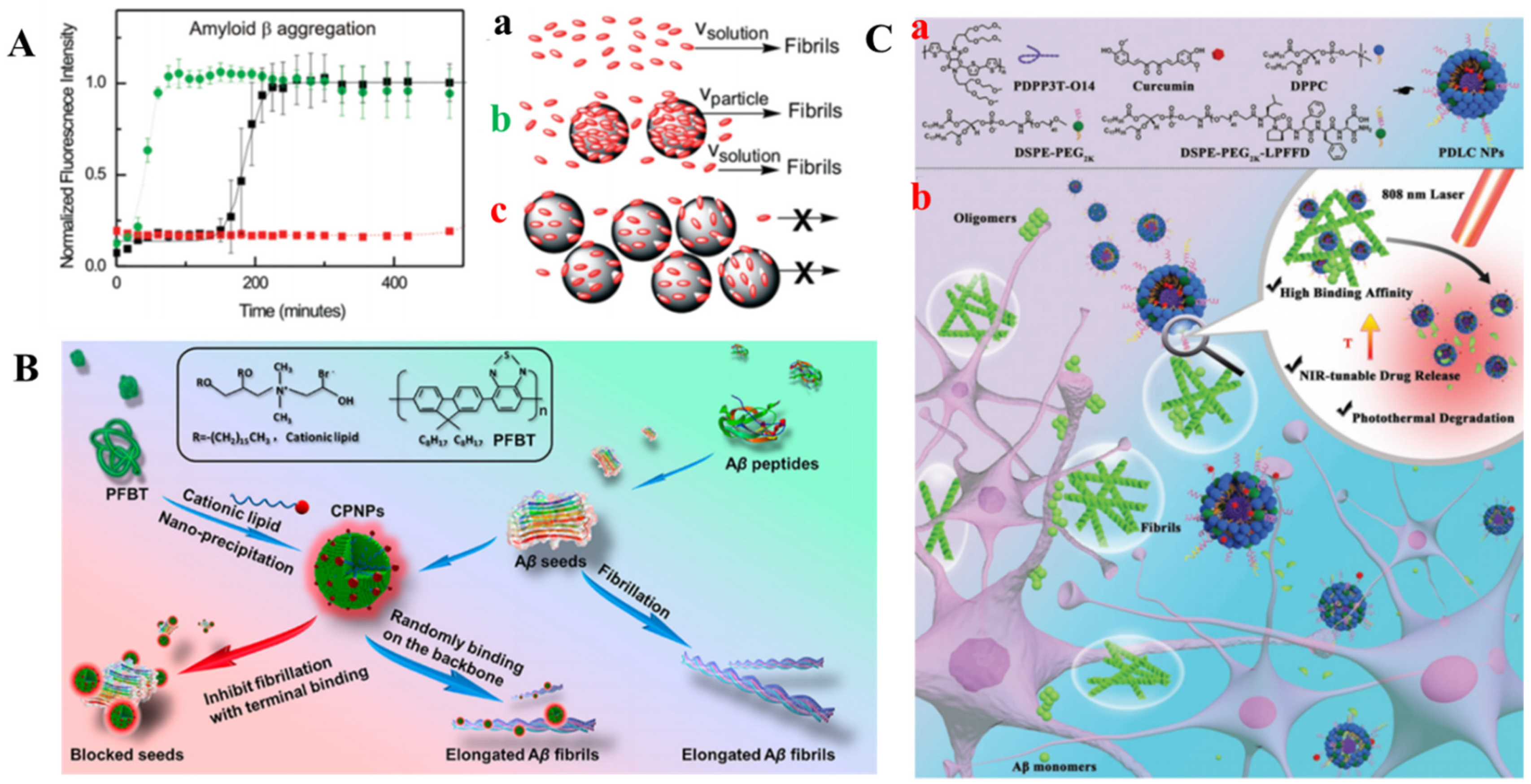

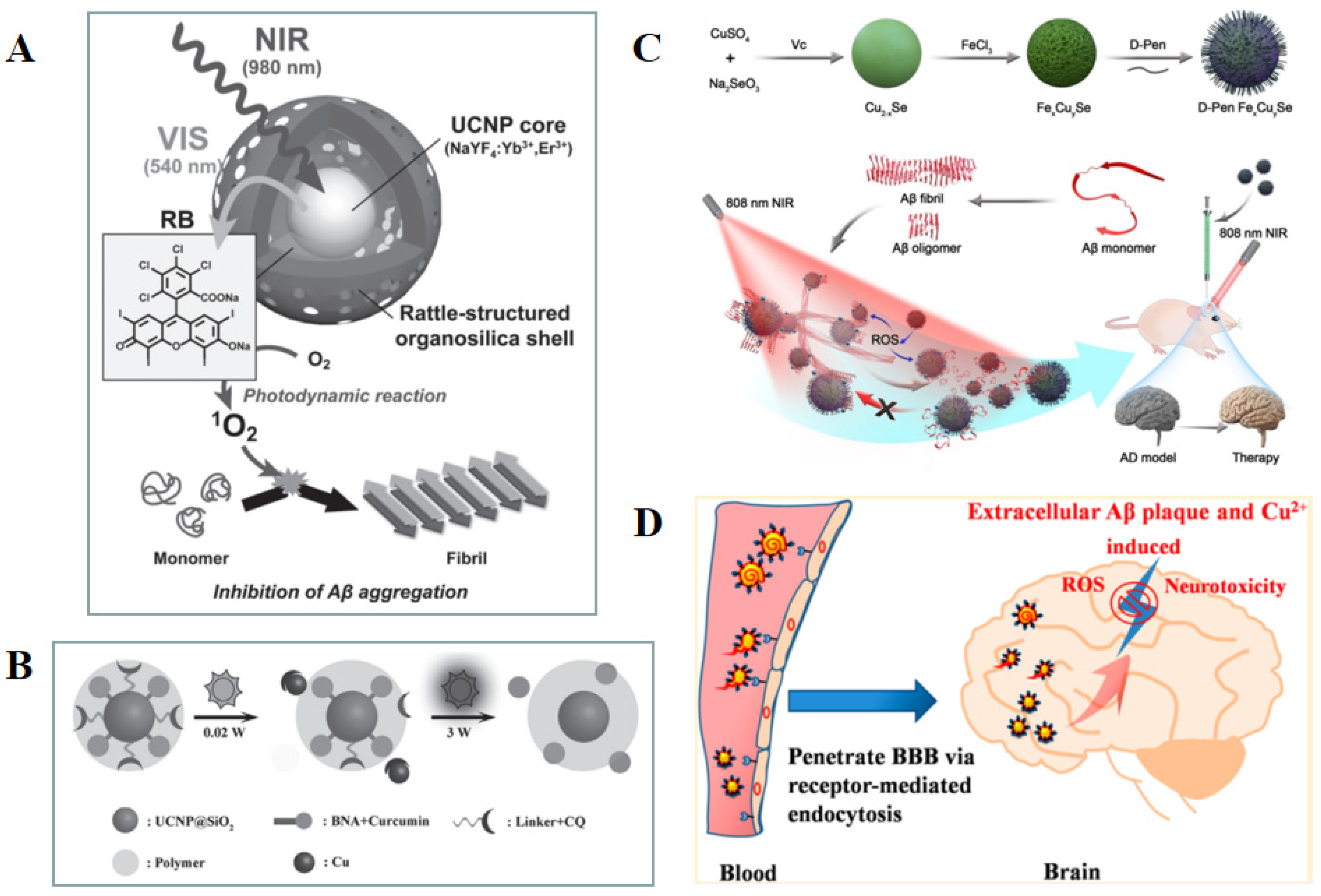

2.7.2. Polymer Nanoparticles

2.8. Others

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tao, Y.X.; Conn, P.M. Pharmacoperones as Novel Therapeutics for Diverse Protein Conformational Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 697–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, D.F.; Khurana, V. Specification of Physiologic and Disease States by Distinct Proteins and Protein Conformations. Cell 2017, 171, 1001–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klementieva, O.; Willen, K.; Martinsson, I.; Israelsson, B.; Engdahl, A.; Cladera, J.; Uvdal, P.; Gouras, G.K. Pre-Plaque Conformational Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease-Linked Aβ and App. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow, K.; de Leon, M.J.; Zetterberg, H. Alzheimer’s Disease. Lancet 2006, 368, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, M.C.; Vucic, S.; Cheah, B.C.; Turner, M.R.; Eisen, A.; Hardiman, O.; Burrell, J.R.; Zoing, M.C. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Lancet 2011, 377, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yepes, M. The Plasminogen Activating System in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 1973–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, R.J.; Knopman, D.S.; Bu, G. An Agnostic Reevaluation of the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis: The Role of App Homeostasis. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 16, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canevelli, M.; Bruno, G.; Cesari, M. The Sterile Controversy on the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 83, 472–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, X.; Tung, Y.C.; Xie, S.; Liu, F.; Iqbal, K. Hyperphosphorylation Determines Both the Spread and the Morphology of Tau Pathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2016, 12, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styr, B.; Slutsky, I. Imbalance between Firing Homeostasis and Synaptic Plasticity Drives Early-Phase Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammang, B.; Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Sevalle, J.; Debayle, D.; Dabert-Gay, A.S.; Thevenet, A.; Lauritzen, I.; Checler, F. Evidence That the Amyloid-Β Protein Precursor Intracellular Domain, Aicd, Derives from Β-Secretase-Generated C-Terminal Fragment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 30, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checler, F. Processing of the Β-Amyloid Precursor Protein and Its Regulation in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurochem. 1995, 65, 1431–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwatsubo, T.; Odaka, A.; Suzuki, N.; Mizusawa, H.; Nukina, N.; Ihara, Y. Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in Senile Plaques with End-Specific Aβ Monoclonals: Evidence That an Initially Deposited Species Is Aβ42(43). Neuron 1994, 13, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haass, C.; Selkoe, D.J. Soluble Protein Oligomers in Neurodegeneration: Lessons from the Alzheimer’s Amyloid Β-Peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, P.; Yang, J.; Xu, Y.; Grutzendler, J.; Shao, Y.; Moore, A.; Ran, C. Oxalate-Curcumin-Based Probe for Micro- and Macroimaging of Reactive Oxygen Species in Alzheimer’s Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 12384–12389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yan, L.M.; Velkova, A.; Tatarek-Nossol, M.; Andreetto, E.; Kapurniotu, A. Iapp Mimic Blocks Aβ Cytotoxic Self-Assembly: Cross-Suppression of Amyloid Toxicity of Aβ and Iapp Suggests a Molecular Link between Alzheimer’s Disease and Type Ii Diabetes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007, 46, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richman, M.; Wilk, S.; Chemerovski, M.; Warmlander, S.K.; Wahlstrom, A.; Graslund, A.; Rahimipour, S. In Vitro and Mechanistic Studies of an Antiamyloidogenic Self-Assembled Cyclic D, L-A-Peptide Architecture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3474–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Dong, X.; Sun, Y. D-Enantiomeric Rthlvffark-Nh2: A Potent Multifunctional Decapeptide Inhibiting Cu2+-Mediated Amyloid Β-Protein Aggregation and Rmodeling Cu2+-Mediated Amyloid Β Aggregates. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 1390–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxbaum, J.N.; Ye, Z.; Reixach, N.; Friske, L.; Levy, C.; Das, P.; Golde, T.; Masliah, E.; Roberts, A.R.; Bartfai, T. Transthyretin Protects Alzheimer’s Mice from the Behavioral and Biochemical Effects of Aβ Toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2681–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, J.; Warmlander, S.K.; Graslund, A.; Abrahams, J.P. Human Lysozyme Inhibits the In Vitro Aggregation of Aβ Peptides, Which in Vivo Are Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 6507–6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Dong, X.; Sun, Y. Modification of Serum Albumin by High Conversion of Carboxyl to Amino Groups Creates a Potent Inhibitor of Amyloid Β-Protein Fbrillogenesis. Bioconjug. Chem. 2019, 30, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronwall, C.; Jonsson, A.; Lindstrom, S.; Gunneriusson, E.; Stahl, S.; Herne, N. Selection and Characterization of Affibody Ligands Binding to Alzheimer Amyloid Β Peptides. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 128, 162–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wu, D.; Yi, X.; Tang, H.; Wu, L.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J. Tmpyp Inhibits Amyloid-Β Aggregation and Alleviates Amyloid-Induced Cytotoxicity. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 4188–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, A.; Shimizu, Y.; Oisaki, K.; Sohma, Y.; Kanai, M. Switchable Photooxygenation Catalysts That Sense Higher-Order Amyloid Structures. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, A.; Sasaki, D.; Shiohara, A.; Iwatsubo, T.; Tomita, T.; Sohma, Y.; Kanai, M. Attenuation of the Aggregation and Neurotoxicity of Amyloid-Β Peptides by Catalytic Photooxygenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Lee, B.I.; Park, C.B. Photo-Induced Inhibition of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Aggregation In Vitro by Rose Bengal. Biomaterials 2015, 38, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.I.; Lee, S.; Suh, Y.S.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, A.-k.; Kwon, O.Y.; Yu, K.; Park, C.B. Photoexcited Porphyrins as a Strong Suppressor of Β-Amyloid Aggregation and Synaptic Toxicity. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 11634–11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.I.; Suh, Y.S.; Chung, Y.J.; Yu, K.; Park, C.B. Shedding Light on Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloidosis: Photosensitized Methylene Blue Inhibits Self-Assembly of Β-Amyloid Peptides and Disintegrates Their Aggregates. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zorkina, Y.; Abramova, O.; Ushakova, V.; Morozova, A.; Zubkov, E.; Valikhov, M.; Melnikov, P.; Majouga, A.; Chekhonin, V. Nano Carrier Drug Delivery Systems for the Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Advantages and Limitations. Molecules 2020, 25, 5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wei, C.; Liu, Y.; Xie, W.; Xu, M.; Zhou, H.; Liu, J. Progressive Release of Mesoporous Nano-Selenium Delivery System for the Multi-Channel Synergistic Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomaterials 2019, 197, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagorska, A.; Jaromin, A. Perspectives for New and More Efficient Multifunctional Ligands for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manek, E.; Darvas, F.; Petroianu, G.A. Use of Biodegradable, Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2020, 25, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.H.; Sun, X.; Yu, Y.P.; Hu, J.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.F.; Li, Y.M. Tio2 Nanoparticles Promote Beta-Amyloid Fibrillation In Vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 373, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M.-C.; Astruc, D. Gold Nanoparticles: Assembly, Supramolecular Chemistry, Quantum-Size-Related Properties, and Applications toward Biology, Catalysis, and Nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 293–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dykmana, L.; Khlebtsov, N. Gold Nanoparticles in Biomedical Applications: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2256–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, A.; Nam, J.M.; Kim, Y.; Park, A.; Nam, J.M. Amyloid-Β Aggregation with Gold Nanoparticles on Brain Lipid Bilayer. Small 2014, 10, 1779–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsadeghi, S.; Dinarvand, R.; Ghahremani, M.H.; Hormozi-Nezhad, M.R.; Mahmoudi, Z.; Hajipour, M.J.; Atyabi, F.; Ghavami, M.; Mahmoudi, M. Protein Corona Composition of Gold Nanoparticles/Nanorods Affects Amyloid Beta Fibrillation Process. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 5004–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.H.; Lee, H.; Nam, J.M. How Do the Size, Charge and Shape of Nanoparticles Affect Amyloid Beta Aggregation on Brain Lipid Bilayer? Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Zhang, M.; Gong, D.; Chen, R.; Hu, X.; Sun, T. The Size-Effect of Gold Nanoparticles and Nanoclusters in the Inhibition of Amyloid-Beta Fibrillation. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 4107–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.H.; Chang, Y.J.; Yoshiike, Y.; Chang, Y.C.; Chen, Y.R. Negatively Charged Gold Nanoparticles Inhibit Alzheimer’s Amyloid-Β Fibrillization, Induce Fibril Dissociation, and Mitigate Neurotoxicity. Small 2012, 8, 3631–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wei, G.; Yang, X. Influence of Au Nanoparticles on the Aggregation of Amyloid-Beta-(25-35) Peptides. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 10397–10403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Han, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Y. Effects of Gold Nanospheres and Nanocubes on Amyloid-Beta Peptide Fibrillation. Langmuir 2019, 35, 2334–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, G.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, B.; Xu, L.-P.; Zhang, X. Size-Effect of Gold Nanorods on Modulating the Kinetic Process of Amyloid-Β Aggregation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 734, 136702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, L.; Ardevol, A.; Parrinello, M.; Lutz, H.; Lu, H.; Weidner, T.; Corni, S. The Interaction with Gold Suppresses Fiber-Like Conformations of the Amyloid Β(16-22) Peptide. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 8737–8748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, M.; Sun, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Exploring the Mechanism of Inhibition of Au Nanoparticles on the Aggregation of Amyloid-Β(16-22) Peptides at the Atom Level by All-Atom Molecular Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anand, B.G.; Wu, Q.; Karthivashan, G.; Shejale, K.P.; Amidian, S.; Wille, H.; Kar, S. Mimosine Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles (Mimo-Aunps) Suppress Β-Amyloid Aggregation and Neuronal Toxicity. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4491–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmal, S.; Maity, A.R.; Singh, B.K.; Basu, S.; Jana, N.R.; Jana, N.R. Inhibition of Amyloid Fibril Growth and Dissolution of Amyloid Fibrils by Curcumin–Gold Nanoparticles. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 6184–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, N.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, X.; Zheng, J.; Sun, Y. Design of a Molecular Hybrid of Dual Peptide Inhibitors Coupled on Aunps for Enhanced Inhibition of Amyloid Β-Protein Aggregation and Cytotoxicity. Small 2017, 13, 1601666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adura, C.; Guerrero, S.; Salas, E.; Medel, L.; Riveros, A.; Mena, J.; Arbiol, J.; Albericio, F.; Giralt, E.; Kogan, M.J. Stable Conjugates of Peptides with Gold Nanorods for Biomedical Applications with Reduced Effects on Cell Viability. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2013, 5, 4076–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, S.; Araya, E.; Fiedler, J.L.; Arias, J.I.; Adura, C.; Albericio, F.; Giralt, E.; Arias, J.L.; Fernandez, M.S.; Kogan, M.J. Improving the Brain Delivery of Gold Nanoparticles by Conjugation with an Amphipathic Peptide. Nanomedicine 2010, 5, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmedo, I.; Araya, E.; Sanz, F.; Medina, E.; Arbiol, J.; Toledo, P.; Alvarez-Lueje, A.; Giralt, E.; Kogan, M.J. How Changes in the Sequence of the Peptide Clpffd-Nh2 Can Modify the Conjugation and Stability of Gold Nanoparticles and Their Affinity for Beta-Amyloid Fibrils. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008, 19, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, M.J.; Bastus, N.G.; Amigo, R.; Grillo-Bosch, D.; Araya, E.; Turiel, A.; Labarta, A.; Giralt, E.; Puntes, V.F. Nanoparticle-Mediated Local and Remote Manipulation of Protein Aggregation. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, E.; Olmedo, I.; Bastus, N.G.; Guerrero, S.; Puntes, V.F.; Giralt, E.; Kogan, M.J. Gold Nanoparticles and Microwave Irradiation Inhibit Beta-Amyloid Amyloidogenesis. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Triulzi, R.C.; Dai, Q.; Zou, J.; Leblanc, R.M.; Gu, Q.; Orbulescu, J.; Huo, Q. Photothermal Ablation of Amyloid Aggregates by Gold Nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B 2008, 63, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, J.; Hassan, N.; Morales-Zavala, F.; Steitz, J.; Araya, E.; Kogan, M.J.; Simon, U. Clpffd–Peg Functionalized Nir-Absorbing Hollow Gold Nanospheres and Gold Nanorods Inhibit Β-Amyloid Aggregation. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 2432–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Xie, W.; Sun, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, J. Penetratin Peptide-Functionalized Gold Nanostars: Enhanced Bbb Permeability and Nir Photothermal Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease Using Ultralow Irradiance. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2016, 8, 19291–19302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; He, R.; Li, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, G.; Ji, M.; Yang, X. Highly Efficient Destruction of Amyloid-Β Fibrils by Femtosecond Laser-Induced Nanoexplosion of Gold Nanorods. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.I.; Pettingell, W.H.; Multhaup, G.; d ParadisParadis, M.; Vonsattel, J.P.; Gusella, J.F.; Beyreuther, K.; Masters, C.L.; Tanzi, R.E. Rapid Induction of Alzheimer Aβ Amyloid Formation by Zinc. Science 1994, 265, 1464–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Li, M.; Wu, L.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Liberation of Copper from Amyloid Plaques: Making a Risk Factor Useful for Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 9146–9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepp, K.P. Bioinorganic Chemistry of Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5193–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cahoon, L. The Curious Case of Clioquinol. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedeoglu, A.; Cormier, K.; Payton, S.; Tseitlin, K.A.; Kremsky, J.N.; Lai, L.; Li, X.; Moir, R.D.; Tanzi, R.E.; Bush, A.I.; et al. Preliminary Studies of a Novel Bifunctional Metal Chelator Targeting Alzheimer’s Amyloidogenesis. Exp. Gerontol. 2004, 39, 1641–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, P.; Li, M.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Gold Nanocage-Based Dual Responsive “Caged Metal Chelator”Release System: Noninvasive Remote Control with near Infrared for Potential Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 5412–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Li, X.; Han, A.; Yang, Y.; Fang, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, S. CLVFFA-Functionalized Gold Nanoclusters Inhibit Aβ40 Fibrillation, Fibrils’ Prolongation, and Mature Fibrils’ Disaggregation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 4633–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; He, M.; Luo, Z.; Ma, Z.; Gao, G.; Zhang, W. Au23(Cr)14 Nanocluster Restores Fibril Aβ’s Unfolded State with Abolished Cytotoxicity and Dissolves Endogenous Aβ Plaques. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Xu, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Besenbacher, F.; Dong, M. Modulating Aβ33–42 Peptide Assembly by Graphene Oxide. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 7236–7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bag, S.; Sett, A.; DasGupta, S.; Dasgupta, S. Hydropathy: The Controlling Factor Behind the Inhibition of Aβ Fibrillation by Graphene Oxide. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 103242–103252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, C.; Zheng, J. Structure, Orientation, and Surface Interaction of Alzheimer Amyloid-Beta Peptides on the Graphite. Langmuir 2012, 28, 6595–6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ge, C.; Liu, J.; Chong, Y.; Gu, Z.; Jimenez-Cruz, C.A.; Chai, Z.; Zhou, R. Destruction of Amyloid Fibrils by Graphene through Penetration and Extraction of Peptides. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 18725–18737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Akhavan, O.; Ghavami, M.; Rezaee, F.; Ghiasi, S.M. Graphene Oxide Strongly Inhibits Amyloid Beta Fibrillation. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 7322–7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, L.; Dong, M. Size Effect of Graphene Oxide on Modulating Amyloid Peptide Assembly. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9632–9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, G.; Zhao, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lv, Z.; Jiang, F.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Sun, T. Chiral Effect at Protein/Graphene Interface: A Bioinspired Perspective to Understand Amyloid Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 10736–10742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yang, X.; Ren, J.; Qu, K.; Qu, X. Using Graphene Oxide High near-Infrared Absorbance for Photothermal Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Shi, P.; Li, M.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. A Cytotoxic Amyloid Oligomer Self-Triggered and Nir-Enhanced Amyloidosis Therapeutic System. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 2431–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, Q.; Wang, X.; Yu, N.; Yang, L.; Yang, R.; Wang, C. Reduced Aggregation and Cytotoxicity of Amyloid Peptides by Graphene Oxide/Gold Nanocomposites Prepared by Pulsed Laser Ablation in Water. Small 2014, 10, 4386–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Mozhi, A.; Yang, L.; Han, Q.; Liang, X.; Li, C.; Yang, R.; Wang, C. Graphene Oxide-Iron Oxide Nanocomposite as an Inhibitor of Aβ42 Amyloid Peptide Aggregation. Colloids Surf. B 2017, 159, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Wang, W.; Sang, J.; Jia, L.; Lu, F. Hydroxylated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Inhibit Aβ42 Fibrillogenesis, Disaggregate Mature Fibrils, and Protect against Aβ42-Induced Cytotoxicity. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, N.W.; O’Connell, M.; Wisdom, J.A.; Dai, H. Carbon Nanotubes as Multifunctional Biological Transporters and near-Infrared Agents for Selective Cancer Cell Destruction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11600–11605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, J.; Warmlander, S.K.; Yu, C.H.; Muhammad, K.; Graslund, A.; Pieter Abrahams, J. The Abeta Peptide Forms Non-Amyloid Fibrils in the Presence of Carbon Nanotubes. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 6720–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xie, L.; Lin, D.; Luo, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; Wei, G. Effects of Hydroxylated Carbon Nanotubes on the Aggregation of Aβ16-22 Peptides: A Combined Simulation and Experimental Study. Biophys. J. 2014, 107, 1930–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ma, M.; Gao, N.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Pi, Z.; Du, X.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. A Biocompatible Second near-Infrared Nanozyme for Spatiotemporal and Non-Invasive Attenuation of Amyloid Deposition through Scalp and Skull. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 9894–9903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Qian, Z.; Wei, G. The Inhibitory Mechanism of a Fullerene Derivative against Amyloid-Beta Peptide Aggregation: An Atomistic Simulation Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 12582–12591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Luo, Y.; Lin, D.; Xi, W.; Yang, X.; Wei, G. The Molecular Mechanism of Fullerene-Inhibited Aggregation of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Peptide Fragment. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 9752–9762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.E.; Lee, M. Fullerene Inhibits Β-Amyloid Peptide Aggregation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 303, 576–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolski, I.Y.; Podlubnaya, Z.A.; Kosenko, E.A.; Mugantseva, E.A.; Makarova, E.G.; Marsagishvili, L.G.; Shpagina, M.D.; Kaminsky, Y.G.; Andrievsky, G.V.; Klochkov, V.K. Effects of Hydrated Forms of C60 Fullerene on Amyloid Β-Peptide Fibrillization In Vitro and Performance of the Cognitive Task. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2007, 7, 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobylev, A.G.; Kornev, A.B.; Bobyleva, L.G.; Shpagina, M.D.; Fadeeva, I.S.; Fadeev, R.S.; Deryabin, D.G.; Balzarini, J.; Troshin, P.A.; Podlubnaya, Z.A. Fullerenolates: Metallated Polyhydroxylated Fullerenes with Potent Anti-Amyloid Activity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 5714–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bednarikova, Z.; Huy, P.D.; Mocanu, M.M.; Fedunova, D.; Li, M.S.; Gazova, Z. Fullerenol C60(Oh)16 Prevents Amyloid Fibrillization of Aβ40-In Vitro and in Silico Approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 18855–18867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchor, M.-H.; Susana, F.-G.; Francisco, G.-S.; Hiram I, B.; Norma, R.-F.; Jorge A, L.-R.; Perla Y, L.-C.; Gustavo, B.-I. Fullerenemalonates Inhibit Amyloid Beta Aggregation, In Vitro and in Silico Evaluation. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 39667–39677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bobylev, A.G.; Kraevaya, O.A.; Bobyleva, L.G.; Khakina, E.A.; Fadeev, R.S.; Zhilenkov, A.V.; Mishchenko, D.V.; Penkov, N.V.; Teplov, I.Y.; Yakupova, E.I.; et al. Anti-amyloid Activities of Three Different Types of Water-Soluble Fullerene Derivatives. Colloids Surf. B 2019, 183, 110426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, F.; Hou, C.-C.; Foote, C.S. Determination of the Quenching Rate Constants of Singlet Oxygen by Derivatized Nucleosides in Nonaqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 5051–5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto, S.; Sakai, S.; Matsumura, S.; Takahashi, D.; Toshima, K. Target-Selective Photo-Degradation of Hiv-1 Protease by a Fullerene-Sugar Hybrid. Chem. Commun. 2008, 5767–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, Y.; Tanimoto, S.; Takahashi, D.; Toshima, K. Photo-Degradation of Amyloid Β by a Designed Fullerene-Sugar Hybrid. MedChemComm 2010, 1, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Fujii, T.; Oka, K.; Takahashi, D.; Toshima, K. Inhibition of Amyloi Β Aggregation and Cytotoxicity by Photodegradation Using a Designed Fullerene Derivative. Chem. Asian J. 2011, 6, 2312–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Gao, N.; Wang, X.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Near-Infrared Switchable Fullerene-Based Synergy Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Small 2018, 14, 1801852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ray, R.; Gu, Y.; Ploehn, H.J.; Gearheart, L.; Raker, K.; Scrivens, W.A. Electrophoretic Analysis and Purification of Fluorescent Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Fragments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 12736–12737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, L.P.; Dai, W.; Dong, H.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, X. Graphene Quantum Dots for the Inhibition of Β Amyloid Aggregation. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 19060–19065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Q.; Chen, X.; Xu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J. Chiral Penicillamine-Modified Selenium Nanoparticles Enantioselectively Inhibit Metal-Induced Amyloid Beta Aggregation for Treating Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 505, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malishev, R.; Arad, E.; Bhunia, S.K.; Shaham-Niv, S.; Kolusheva, S.; Gazit, E.; Jelinek, R. Chiral Modulation of Amyloid Beta Fibrillation and Cytotoxicity by Enantiomeric Carbon Dots. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 7762–7765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.; Zhou, D.; Luan, P.; Gu, B.; Feng, L.; Fan, S.; Liao, W.; Fang, W.; Yang, L.; Tao, E.; et al. Graphene Quantum Dots Conjugated Neuroprotective Peptide Improve Learning and Memory Capability. Biomaterials 2016, 106, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Wang, W.; Dong, X.; Sun, Y. Nitrogen-Doped Carbonized Polymer Dots: A Potent Scavenger and Detector Targeting Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Plaques. Small 2020, 16, e2002804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.J.; Kim, K.; Lee, B.I.; Park, C.B. Carbon Nanodot-Sensitized Modulation of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Self-Assembly, Disassembly, and Toxicity. Small 2017, 13, 1700983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.J.; Lee, C.H.; Lim, J.; Jang, J.; Kang, H.; Park, C.B. Photomodulating Carbon Dots for Spatiotemporal Suppression of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Aggregation. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 16973–16983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Quinlan-Pluck, F.; Monopoli, M.P.; Sheibani, S.; Vali, H.; Dawson, K.A.; Lynch, I. Influence of the Physiochemical Properties of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles on Amyloid Beta Protein Fibrillation in Solution. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Margel, S.; Skaat, H.; Corem-Salkmon, E.; Grinberg, I.; Last, D.; Goez, D.; Mardor, Y. Antibody-Conjugated, Dual-Modal, near-Infrared Fluorescent Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Antiamyloidgenic Activity and Specific Detection of Amyloid-Β Fibrils. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 4063–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Skaat, H.; Shafir, G.; Margel, S. Acceleration and Inhibition of Amyloid-Β Fibril Formation by Peptide-Conjugated Fluorescent-Maghemite Nanoparticles. J. Nanopart. Res. 2011, 13, 3521–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevas, E.; Mavroidi, B.; Nday, C.M.; Tang, J.; Smith, G.C.; Boukos, N.; Litsardakis, G.; Pelecanou, M.; Salifoglou, A. Modified Magnetic Core-Shell Mesoporous Silica Nano-Formulations with Encapsulated Quercetin Exhibit Anti-Amyloid and Antioxidant Activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 213, 111271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirohata, M.; Hasegawa, K.; Tsutsumi-Yasuhara, S.; Ohhashi, Y.; Ookoshi, T.; Ono, K.; Yamada, M.; Naiki, H. The Anti-Amyloidogenic Effect Is Exerted against Alzheimer’s Beta-Amyloid Fibrils In Vitro by Preferential and Reversible Binding of Flavonoids to the Amyloid Fibril Structure. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 1888–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Inhibition of Metal-Induced Amyloid Aggregation Using Light-Responsive Magnetic Nanoparticle Prochelator Conjugates. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loynachan, C.N.; Romero, G.; Christiansen, M.G.; Chen, R.; Ellison, R.; O’Malley, T.T.; Froriep, U.P.; Walsh, D.M.; Anikeeva, P. Targeted Magnetic Nanoparticles for Remote Magnetothermal Disruption of Amyloid-Β Aggregates. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 2100–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Romero, G.; Christiansen, M.G.; Mohr, A.; Anikeeva, P. Wireless Magnetothermal Deep Brain Stimulation. Science 2015, 347, 1477–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riedinger, A.; Guardia, P.; Curcio, A.; Garcia, M.A.; Cingolani, R.; Manna, L.; Pellegrino, T. Subnanometer Local Temperature Probing and Remotely Controlled Drug Release Based on Azo-Functionalized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 2399–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyne, E.; Prakash, P.S.; Li, J.; Yu, B.; Schmidt, T.L.; Huang, S.; Kim, M.H. Mild Magnetic Nanoparticle Hyperthermia Promotes the Disaggregation and Microglia-Mediated Clearance of Beta-Amyloid Plaques. Nanomedicine 2021, 34, 102397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Gao, N.; Guan, Y.; Ding, C.; Sun, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Rational Design of a “Sense and Treat” System to Target Amyloid Aggregates Related to Alzheimer’s Disease. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 1987–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhule, J.T.; Hill, C.L.; Judd, D.A.; Schinazi, R.F. Polyoxometalates in Medicine. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judd, D.A.; Nettles, J.H.; Nevins, N.; Snyder, J.P.; Liotta, D.C.; Tang, J.; Ermolieff, J.; Schinazi, R.F.; Hill, C.L. Polyoxometalate Hiv-1 Protease Inhibitors. A New Mode of Protease Inhibition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Li, M.; Ren, J.; Wang, E.; Qu, X. Polyoxometalates as Inhibitors of the Aggregation of Amyloid Beta Peptides Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 4184–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zheng, L.; Han, F.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Y.; Yao, J.; Keita, B.; de Oliveira, P.; Nadjo, L. Inhibition of Amyloid-Β Protein Fibrillization Upon Interaction with Polyoxometalates Nanoclusters. Colloids Surface A 2011, 375, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Sun, H.; Dong, K.; Ren, J.; Duan, T.; Xu, C.; Qu, X. Transition-Metal-Substituted Polyoxometalate Derivatives as Functional Anti-Amyloid Agents for Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, J.; Li, K.; Wan, K.; Sun, T.; Zheng, N.; Zhu, F.; Ma, J.; Jiao, J.; Li, T.; Ni, J.; et al. Organoplatinum-substituted polyoxometalate inhibits B-amyloid aggregation for Alzheimer’s therapy. Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 18200–18207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, L.; Zheng, C.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J. Mo Polyoxometalate Nanoclusters Capable of Inhibiting the Aggregation of Aβ-Peptide Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 6886–6897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernardini, G.; Wedd, A.G.; Zhao, C.; Bond, A.M. Photochemical Oxidation of Water and Reduction of Polyoxometalate Anions at Interfaces of Water with Ionic Liquids or Diethylether. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11552–11557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonchio, M.; Carraro, M.; Conte, V.; Scorrano, G. Aerobic Photooxidation in Water by Polyoxotungstates: The Case of Uracil. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2005, 4897–4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, C.; Ren, J.; Wang, E.; Qu, X. Photodegradation of Beta-Sheet Amyloid Fibrils Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease by Using Polyoxometalates as Photocatalysts. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 11394–11396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Gao, N.; Sun, Y.; Du, X.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Redox-Activated near-Infrared-Responsive Polyoxometalates Used for Photothermal Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, e1800320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xu, C.; Wu, L.; Ren, J.; Wang, E.; Qu, X. Self-Assembled Peptide-Polyoxometalate Hybrid Nanospheres: Two in One Enhances Targeted Inhibition of Amyloid Beta-Peptide Aggregation Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Small 2013, 9, 3455–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Sun, H.; Dong, K.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Gold-Nanoparticle-Based Multifunctional Amyloid-Β Inhibitor against Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Guan, Y.; Zhao, A.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Using Multifunctional Peptide Conjugated Au Nanorods for Monitoring Beta-Amyloid Aggregation and Chemo-Photothermal Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Theranostics 2017, 7, 2996–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Qu, X. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle: A Remarkably Versatile Rare Earth Nanomaterial for Biological Applications. NPG Asia Mater. 2014, 6, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, B.; Santucci, S.; Benedetti, E.; Di Loreto, S.; Phani, R.; Falone, S.; Amicarelli, F.; Ceru, M.; Cimini, A. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Trigger Neuronal Survival in Ahuman Alzheimer Disease Model by Modulating Bdnf Pathway. Curr. Nanosci. 2009, 5, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowding, J.M.; Song, W.; Bossy, K.; Karakoti, A.; Kumar, A.; Kim, A.; Bossy, B.; Seal, S.; Ellisman, M.H.; Perkins, G.; et al. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Protect against Aβ-Induced Mitochondrial Fragmentation and Neuronal Cell Death. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 1622–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shi, P.; Xu, C.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Cerium Oxide Caged Metal Chelator: Anti-Aggregation and Anti-Oxidation Integrated H2o2-Responsive Controlled Drug Release for Potential Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2536–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Gao, N.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Rationally Designed Cenp@Mnmos4 Core-Shell Nanoparticles for Modulating Multiple Facets of Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 14523–14526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absillis, G.; Parac-Vogt, T.N. Peptide Bond Hydrolysis Catalyzed by the Wells-Dawson Zr(A2-P2w17o61)2 Polyoxometalate. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 9902–9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Li, M.; Dong, K.; Gao, N.; Ren, J.; Zheng, Y.; Qu, X. Ceria/Poms Hybrid Nanoparticles as a Mimicking Metallopeptidase for Treatment of Neurotoxicity of Amyloid-Β Peptide. Biomaterials 2016, 98, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Kwon, H.J.; Hyeon, T. Magnetite/Ceria Nanoparticle Assemblies for Extracorporeal Cleansing of Amyloid-Β in Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1807965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.J.; Zhou, W.H.; Li, G.; Hu, Z.W.; Hong, L.; Yu, X.F.; Li, Y.M. Black Phosphorus Nanomaterials Regulate the Aggregation of Amyloid-Β. ChemNanoMat 2019, 5, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, W.; Sun, Y.; Dong, X. Lvffark-Peg-Stabilized Black Phosphorus Nanosheets Potently Inhibit Amyloid-Β Fibrillogenesis. Langmuir 2020, 36, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Shao, W.; Chen, S.; Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Xie, Y. Ultrathin Black Phosphorus Nanosheets for Efficient Singlet Oxygen Generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11376–11382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xie, H.; Tang, S.; Yu, X.-F.; Guo, Z.; Shao, J.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Chu, P.K. Ultrasmall Black Phosphorus Quantum Dots: Synthesis and Use as Photothermal Agents. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 11688–11692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wen, L.; Zeng, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Deng, L.; Zhao, C.; Li, Z. One-Pot Solventless Preparation of Pegylated Black Phosphorus Nanoparticles for Photoacoustic Imaging and Photothermal Therapy of Cancer. Biomaterials 2016, 91, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ouyang, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, M.; Zeng, K.; Sheng, J.; Liu, Z.; Han, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; et al. Black Phosphorus Nanosheet-Based Drug Delivery System for Synergistic Photodynamic/Photothermal/Chemotherapy of Cancer. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1603864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, M.; Yu, D.; Lu, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Near-Infrared Activated Black Phosphorus as a Nontoxic Photo-Oxidant for Alzheimer’s Amyloid-Β Peptide. Small 2019, 15, 1901116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudedla, S.K.; Murugan, N.A.; Subramanian, V.; Agren, H. Destabilization of Amyloid Fibrils on Interaction with Mos2-Based Nanomaterials. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 1613–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Ge, D.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Dong, M. Differential Modulating Effect of Mos2 on Amyloid Peptide Assemblies. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 3397–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Du, X.; Ma, Y.; Liao, G.; Wang, Q.; Yang, X.; Wang, K. Contradictory Effect of Gold Nanoparticle-Decorated Molybdenum Sulfide Nanocomposites on Amyloid-Β-40 Aggregation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 3113–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.S.; Kaehr, B.; Kim, J.; Foley, B.M.; De, M.; Hopkins, P.E.; Huang, J.; Brinker, C.J.; Dravid, V.P. Chemically Exfoliated Mos2 as near-Infrared Photothermal Agents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 4160–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, M.; Zhao, A.; Dong, K.; Li, W.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Chemically Exfoliated Ws2 Nanosheets Efficiently Inhibit Amyloid Β-Peptide Aggregation and Can Be Used for Photothermal Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 3216–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, R. Multifunctional Inhibitors of Β-Amyloid Aggregation Based on Mos2/Aunr Nanocomposites with High near-Infrared Absorption. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 9185–9193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Yoo, S.H.; Kim, M.G.; Jeong, K.; Ahn, J.Y.; Kim, M.-s.; Chae, P.S.; Lee, T.Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; et al. Cleavage Agents for Soluble Oligomers of Amyloid Β Peptides. Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 7194–7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrick, J.S.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, Y.; Nam, E.; Tak, H.; Kang, J.; Lee, M.; Kim, S.H.; Park, K.; et al. Mechanistic Insights into Tunable Metal-Mediated Hydrolysis of Amyloid-Β Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 2234–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wang, Y.; Gao, N.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. A near-Infrared-Controllable Artificial Metalloprotease Used for Degrading Amyloid-Β Monomers and Aggregates. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 11852–11858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Cai, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Qi, C.; Yang, R.; Wang, C. Molybdenum Disulfide Nanoparticles as Multifunctional Inhibitors against Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2017, 9, 21116–21123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.J.; Lee, B.I.; Ko, J.W.; Park, C.B. Photoactive G-C3n4 Nanosheets for Light-Induced Suppression of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Aggregation and Toxicity. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 1560–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Chen, M.; Liu, L.; Dong, M. Enhanced Photoresponsive Graphene Oxide-Modified G-C3n4 for Disassembly of Amyloid Β Fibrils. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2019, 11, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; Tian, X.; Li, C.; Liu, L. Disassembling and Degradation of Amyloid Protein Aggregates Based on Gold Nanoparticle-Modified G-C3n4. Colloids Surf. B 2020, 192, 111051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Guan, Y.; Ding, C.; Chen, Z.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. An Ultrathin Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheet: A Novel Inhibitor of Metal-Induced Amyloid Aggregation Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 4072–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Guan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gao, N.; Ren, J.; Dong, K.; Qu, X. Platinum-Coordinated Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheet Used for Targeted Inhibition of Amyloid Β-Peptide Aggregation. Nano Res. 2016, 9, 2411–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Zhang, X.; Ge, K.; Yin, Y.; Machuki, J.O.; Yang, Y.; Shi, H.; Geng, D.; Gao, F. Carbon Nitride-Based Nanocaptor: An Intelligent Nanosystem with Metal Ions Chelating Effect for Enhanced Magnetic Targeting Phototherapy of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomaterials 2021, 267, 120483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, C.; Yang, M. Porphyrinic Metal-Organic Framework Pcn-224 Nanoparticles for near-Infrared-Induced Attenuation of Aggregation and Neurotoxicity of Alzheimer’s Amyloid-Beta Peptide. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2018, 10, 36615–36621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-Z.; Jiang, H.-L. Porphyrinic Metal-Organic Framework Catalyzed Heck-Reaction: Fluorescence “Turn-on” Sensing of Cu(Ii) Ion. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 6698–6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Guan, Y.; Bai, F.; Du, Z.; Gao, N.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Metal-Organic Frameworks Harness Cu Chelating and Photooxidation against Amyloid Β Aggregation in Vivo. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 3489–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, J.; Grapsi, E.; Espargaro, A.; Caballero, A.B.; Juarez-Jimenez, J.; Busquets, M.A.; Gamez, P.; Sabate, R.; Estelrich, J. Dual Effect of Prussian Blue Nanoparticles on Aβ40 Aggregation: Β-Sheet Fibril Reduction and Copper Dyshomeostasis Regulation. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, M.P.T.; Sarkar, N. Quantum Dots as Promising Theranostic Tools Againstamyloidosis:A Review. Protein Pept. Lett. 2019, 26, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Zhao, D.; Chan, W.H.; Choi, M.M.; Li, H.W. Inhibition of Beta 1-40 Amyloid Fibrillation with N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine Capped Quantum Dots. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, O.T.W.; Wong, Y.; Chan, H.M.; Cheng, J.; Qi, X.; Chan, W.H.; Yung, K.K.L.; Li, H.W. N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine Capped Quantum Dots Offer Neuronal Cell Protection by Inhibiting Beta(1-40) Amyloid Fibrillation. Biomater. Sci. 2013, 1, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.; Micic, M.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Movia, D.; Giordani, S.; Zhang, H.; Leblanc, R.M. Conjugated Quantum Dots Inhibit the Amyloid Β (1-42) Fibrillation Process. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 2011, 502386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Del Mar Martinez-Senac, M.; Villalain, J.; Gomez-Fernandez, J.C. Structure of the Alzheimer Β-Amyloid Peptide (25-35) and Its Interaction with Negatively Charged Phospholipid Vesicles. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 265, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sabaté, R.; Gallardo, M.; Estelrich, J. Spontaneous Incorporation of Β-Amyloid Peptide into Neutral Liposomes. Colloids Surface A 2005, 270-271, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terakawa, M.S.; Yagi, H.; Adachi, M.; Lee, Y.H.; Goto, Y. Small Liposomes Accelerate the Fibrillation of Amyloid Β(1-40). J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shimanouchi, T.; Onishi, R.; Kitaura, N.; Umakoshi, H.; Kuboi, R. Copper-Mediated Growth of Amyloid Beta Fibrils in the Presence of Oxidized and Negatively Charged Liposomes. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2011, 112, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanifum, E.A.; Dasgupta, I.; Srivastava, M.; Bhavane, R.C.; Sun, L.; Berridge, J.; Pourgarzham, H.; Kamath, R.; Espinosa, G.; Cook, S.C.; et al. Intravenous Delivery of Targeted Liposomes to Amyloid-Beta Pathology in App/Psen1 Transgenic Mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, C.; Mourtas, S.; Cardona, F.; Zona, C.; Sironi, E.; D’Orazio, G.; Markoutsa, E.; Nicotra, F.; Antimisiaris, S.G.; La Ferla, B. Nanoliposomes Presenting on Surface a Cis-Glycofused Benzopyran Compound Display Binding Affinity and Aggregation Inhibition Ability Towards Amyloid Β1-42 Peptide. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 85, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlred, L.; Gunnarsson, A.; Sole-Domenech, S.; Johansson, B.; Vukojevic, V.; Terenius, L.; Codita, A.; Winblad, B.; Schalling, M.; Hook, F.; et al. Simultaneous Imaging of Amyloid-Beta and Lipids in Brain Tissue Using Antibody-Coupled Liposomes and Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9973–9981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, M.; Re, F.; Canovi, M.; Beeg, M.; Gregori, M.; Sesana, S.; Sonnino, S.; Brogioli, D.; Musicanti, C.; Gasco, P.; et al. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles with High Binding Affinity for Amyloid-Β1-42 Peptide. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 6519–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereczki, E.; Re, F.; Masserini, M.E.; Winblad, B.; Pei, J.J. Liposomes Functionalized with Acidic Lipids Rescue Aβ-Induced Toxicity in Murine Neuroblastoma Cells. Nanomedicine 2011, 7, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtas, S.; Canovi, M.; Zona, C.; Aurilia, D.; Niarakis, A.; La Ferla, B.; Salmona, M.; Nicotra, F.; Gobbi, M.; Antimisiaris, S.G. Curcumin-Decorated Nanoliposomes with Very High Affinity for Amyloid-Β1-42 Peptide. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.; Moore, S.; Mourtas, S.; Niarakis, A.; Re, F.; Zona, C.; La Ferla, B.; Nicotra, F.; Masserini, M.; Antimisiaris, S.G.; et al. Effect of Curcumin-Associated and Lipid Ligand-Functionalized Nanoliposomes on Aggregation of the Alzheimer’s Aβ Peptide. Nanomedicine 2011, 7, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canovi, M.; Markoutsa, E.; Lazar, A.N.; Pampalakis, G.; Clemente, C.; Re, F.; Sesana, S.; Masserini, M.; Salmona, M.; Duyckaerts, C.; et al. The Binding Affinity of Anti-Aβ1-42 Mab-Decorated Nanoliposomes to Aβ1–42 Peptides In Vitro and to Amyloid Deposits in Post-Mortem Tissue. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 5489–5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, F.; Cambianica, I.; Sesana, S.; Salvati, E.; Cagnotto, A.; Salmona, M.; Couraud, P.O.; Moghimi, S.M.; Masserini, M.; Sancini, G. Functionalization with Apoe-Derived Peptides Enhances the Interaction with Brain Capillary Endothelial Cells of Nanoliposomes Binding Amyloid-Beta Peptide. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 156, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, E.; Re, F.; Sesana, S.; Cambianica, I.; Sancini, G.; Masserini, M.; Gregori, M. Liposomes Functionalized to Overcome the Blood-Brain Barrier and to Target Amyloid-Beta Peptide: The Chemical Design Affects the Permeability across an In Vitro Model. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mourtas, S.; Lazar, A.N.; Markoutsa, E.; Duyckaerts, C.; Antimisiaris, S.G. Multifunctional Nanoliposomes with Curcumin-Lipid Derivative and Brain Targeting Functionality with Potential Applications for Alzheimer Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 80, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bana, L.; Minniti, S.; Salvati, E.; Sesana, S.; Zambelli, V.; Cagnotto, A.; Orlando, A.; Cazzaniga, E.; Zwart, R.; Scheper, W.; et al. Liposomes Bi-Functionalized with Phosphatidic Acid and an Apoe-Derived Peptide Affect Abeta Aggregation Features and Cross the Blood-Brain-Barrier: Implications for Therapy of Alzheimer Disease. Nanomedicine 2014, 10, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Mancini, S.; Minniti, S.; La Vitola, P.; Zotti, M.; Sancini, G.; Mauri, M.; Cagnotto, A.; Colombo, L.; Fiordaliso, F.; et al. Multifunctional Liposomes Reduce Brain Β-Amyloid Burden and Ameliorate Memory Impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 14022–14031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaleiro-Lago, C.; Quinlan-Pluck, F.; Lynch, I.; Lindman, S.; Minogue, A.M.; Thulin, E.; Walsh, D.M.; Dawson, K.A.; Linse, S. Inhibition of Amyloid Beta Protein Fibrillation by Polymeric Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 15437–15443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaleiro-Lago, C.; Quinlan-Pluck, F.; Lynch, I.; Dawson, K.A.; Linse, S. Dual Effect of Amino Modified Polystyrene Nanoparticles on Amyloid Beta Protein Fibrillation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2010, 1, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Ghormade, V.; Kolge, H.; Paknikar, K.M. Dual Effect of Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles on the Inhibition of Β-Amyloid Peptide Aggregation and Disintegration of the Preformed Fibrils. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 3362–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Wei, L.; Li, Y.; Xiao, L. Efficient Modulation of Β-Amyloid Peptide Fibrillation with Polymer Nanoparticles Revealed by Super-Resolution Optical Microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 8582–8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xiao, L. Efficient Suppression of Amyloid-Beta Peptide Aggregation and Cytotoxicity with Photosensitive Polymer Nanodots. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 5776–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.T.; Lv, Y.; Tan, C.; Chen, G.R.; He, X.P. Irreversible Destruction of Amyloid Fibril Plaques by Conjugated Polymer Based Fluorogenic Nanogrenades. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 4502–4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Hu, X.; Saeed, M.; Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W. Engineering Versatile Nanoparticles for near-Infrared Light-Tunable Drug Release and Photothermal Degradation of Amyloid Β. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1908473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chang, Y.; Yu, J.; Jiang, M.; Xia, N. Two-in-One Polydopamine Nanospheres for Fluorescent Determination of Beta-Amyloid Oligomers and Inhibition of Beta-Amyloid Aggregation. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 2017, 251, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, M.; Yu, D.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Target-Driven Supramolecular Self-Assembly for Selective Amyloid-Β Photooxygenation against Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 11003–11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuk, S.; Lee, B.I.; Lee, J.S.; Park, C.B. Rattle-Structured Upconversion Nanoparticles for near-Ir-Induced Suppression of Alzheimer’s Β-Amyloid Aggregation. Small 2017, 13, 1603139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Gao, N.; Sun, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. A near-Infrared Responsive Drug Sequential Release System for Better Eradicating Amyloid Aggregates. Small 2017, 13, 1701817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hao, C.; Qu, A.; Sun, M.; Xu, L.; Xu, C.; Kuang, H. Light-Induced Chiral Iron Copper Selenide Nanoparticles Prevent Β-Amyloidopathy in Vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 7131–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xie, W.; Zhu, X.; Xu, M.; Liu, J. Sulfur Nanoparticles with Novel Morphologies Coupled with Brain-Targeting Peptides Rvg as a New Type of Inhibitor against Metal-Induced Aβ Aggregation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, Z.; Lin, J.; Han, G.; Huang, P. Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Carbides and Nitrides (Mxenes) for Biomedical Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 5109–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, J. Nanomaterials for Modulating the Aggregation of β-Amyloid Peptides. Molecules 2021, 26, 4301. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26144301

Huang Y, Chang Y, Liu L, Wang J. Nanomaterials for Modulating the Aggregation of β-Amyloid Peptides. Molecules. 2021; 26(14):4301. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26144301

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yaliang, Yong Chang, Lin Liu, and Jianxiu Wang. 2021. "Nanomaterials for Modulating the Aggregation of β-Amyloid Peptides" Molecules 26, no. 14: 4301. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26144301

APA StyleHuang, Y., Chang, Y., Liu, L., & Wang, J. (2021). Nanomaterials for Modulating the Aggregation of β-Amyloid Peptides. Molecules, 26(14), 4301. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26144301