Analysis of IV Drugs in the Hospital Workflow by Raman Spectroscopy: The Case of Piperacillin and Tazobactam

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The non-invasive analysis of the solid formulation (powder) in its glass vial before reconstitution,

- The non-invasive analysis of the reconstituted liquid formulation in its glass vial, and

- The analysis of the final (further diluted in the IV infusion bag in order to lie in the therapeutic concentration range) formulation just before administration; either it is placed in the drip chamber of the IV infusion set used (on line analysis) or in a Raman optic cell. The latter would be filled with 1–2 mL of the liquid drug, removed from the IV bag using an aseptic syringe (at-line analysis).

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of the Non-Reconstituted Solid Formulation through the Commercial Glass Bottle

2.1.1. Identification of APIs

2.1.2. Quantification of APIs

- Linearity

- Intra- and Inter-day Precision

- Accuracy

- 1.

- For 30% TAZ/70% PIP, x = (1.410 ± 0.070) (% w/w)−1, RSD = 4.68%, and Er = 1.33%.

- 2.

- For 15% TAZ/85% PIP, x = (1.189 ± 0.039) (% w/w)−1, RSD = 3.32%, and Er= 1.07%

- 3.

- For 10% TAZ/90% PIP, x = (1.080 ± 0.026) (% w/w)−1, RSD = 2.38%, and Er= 2.80%.

- LoD and LoQ

- Calibration Range

2.2. Analysis of the Reconstituted Formulation through the Commercial Glass Bottle

2.2.1. Identification of APIs

2.2.2. Quantification of APIs

- Intra- and Inter-day Precision

- Accuracy

- 1.

- For 266.67 mg/mL, C = (264.12 ± 25.19) mg/mL, RSD = 9.54% and Er = 0.96%.

- 2.

- For 44.44 mg/mL, C = (45.02 ± 1.23) mg/mL, RSD = 2.74% and Er = 1.31% and

- 3.

- For 5.00 mg/mL, C = (5.02 ± 0.33) mg/mL, RSD = 6.66% and Er = 0.40%.

- 1.

- For 60.00 mg/mL, C = (63.70 ± 6.22) mg/mL, RSD = 9.76% and Er = 6.17%.

- 2.

- For 33.33 mg/mL, C = (35.55 ± 3.02) mg/mL, RSD = 8.49% and Er = 6.66% and

- 3.

- For 7.00 mg/mL, C = (7.31 ± 0.83) mg/mL, RSD = 11.37% and Er = 4.43%.

- LoD and LoQ

- Calibration Range

2.2.3. Solubility of APIs after Reconstitution

2.3. Analysis of the Liquid Formulation in the IV Bag

2.3.1. Quantification of APIs through the Raman Optic Cell (At-line Analysis)

- Linearity

- Intra- and Inter-day Precision

- Accuracy

- 1.

- For 44.44 mg/mL, C = (43.93 ± 0.78) mg/mL, RSD = 1.77% and Er = 1.15%.

- 2.

- For 20.00 mg/mL, C = (20.24 ± 0.15) mg/mL, RSD = 0.75% and Er = 1.20% and

- 3.

- For 5.00 mg/mL, C = (5.00 ± 0.08) mg/mL, RSD = 1.65% and Er = 0.00%.

- 1.

- For 5.56 mg/mL, C = (5.68 ± 0.28) mg/mL, RSD = 5.00% and Er = 2.16%.

- 2.

- For 4.80 mg/mL, C = (4.80 ± 0.20) mg/mL, RSD = 4.06% and Er = 0.00%.

- 3.

- For 3.75 mg/mL, C = (3.91 ± 0.22) mg/mL, RSD = 5.61% and Er = 4.27%.

- LoD and LoQ

- Calibration Range

2.3.2. Quantification of APIs through IV Drip Chamber (On-Line Analysis)

- Linearity

- Intra- and Inter-day Precision

- Accuracy

- 1.

- For 44.44 mg/mL, C = (46.24 ± 0.93) mg/mL, RSD = 2.00% and Er = 4.05%.

- 2.

- For 20.00 mg/mL, C = (19.92 ± 0.07) mg/mL, RSD = 0.35% and Er = 0.40% and

- 3.

- For 5.00 mg/mL, C = (4.60 ± 0.24) mg/mL, RSD = 5.14% and Er = 8.00%.

- LoD and LoQ

- Calibration Range

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Standard Mixtures

4.2. Preparation of Standard Solutions

4.3. Experimental Methodology for the Dissolution Test after Reconstitution

4.4. Methodology of Raman Spectra Acquisition

4.4.1. Method of High Reflectiveness Gold-Coated Slide

4.4.2. Method of Glass Bottle

4.4.3. Method of Drip Chamber

4.4.4. Method of Raman Optic Cell

4.5. Spectra Processing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

Appendix A

References

- Doyle, G.R.; McCutcheon, J.A. Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care; BCcampus: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2015; pp. 445, 501. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, R.W.; Becker, S.C. An Overview of Intravenous-related Medication Administration Errors as Reported to MEDMARX®, a National Medication Error-reporting Program. J. Infus. Nurs. 2006, 29, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, N.; Beer, I.; Hoppe-Tichy, T.; Trbovich, P. Systematic evidence review of rates and burden of harm of intravenous admixture drug preparation errors in healthcare settings. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alemu, W.; Belachew, T.; Yimam, I. Medication administration errors and contributing factors: A cross sectional study in two public hospitals in Southern Ethiopia. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 7, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, V.; Barber, N.; Taxis, K. An observational study of intravenous medication errors in the United Kingdom and in Germany. Pharm. World Sci. 2003, 25, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahimi, F.; Ariapanah, P.; Faizi, M.; Shafaghi, B.; Namdar, R.; Ardakani, M.T. Errors in preparation and administration of intravenous medications in the intensive care unit of a teaching hospital: An observational study. Aust. Crit. Care 2008, 21, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Q.; Barker, K.N.; Flynn, E.A.; Westrick, S.; Chang, M.; Thomas, R.E.; Braxton-Lloyd, K.; Sesek, R. Incidence of Intravenous Medication Errors in a Chinese Hospital. Value Health Reg. Issues 2015, 6, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barber, N.; Taxis, K. Incidence and severity of intravenous drug errors in a German hospital. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 59, 815–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselmi, M.L.; Peduzzi, M.; Dos Santos, C.B. Errors in the administration of intravenous medication in Brazilian hospitals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, J.I.; Rob, M.I.; Woods, A.; Parry, D. Errors in the administration of intravenous medications in hospital and the role of correct procedures and nurse experience. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2011, 20, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mendes, J.R.; Lopes, M.C.B.T.; Vancini-Campanharo, C.R.; Okuno, M.F.P.; Batista, R.E.A. Types and frequency of errors in the preparation and administration of drugs. Einstein 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolf, Z.R. Medication Errors Involving the Intravenous Administration Route: Characteristics of Voluntarily Reported Medication Errors. J. Infus. Nurs. 2016, 39, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri-Nesami, M.; Esmaeili, R.; Tajari, M. Intravenous Medication Administration Errors and Their Causes in Cardiac Critical Care Units in Iran. Mater. Socio-Medica 2015, 27, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gado, A.; Ebeid, B.; Axon, A. Accidental IV administration of epinephrine instead of midazolam at colonoscopy. Alex. J. Med. 2016, 52, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, N.; Yildizdas, D.; Arslan, D.; Horoz, O.O.; Yilmaz, H.L.; Bilen, S. Intravenous Paracetamol Overdose: A Pediatric Case Report. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2019, 35, e42–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; Magalhães, S. Raman Spectroscopy Applied to Health Sciences, Raman Spectroscopy, Gustavo Morari do Nascimento; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, S.; Zhang, S.; Yue, S. Raman Spectroscopy and Imaging for Cancer Diagnosis. J. Healthc. Eng. 2018, 2018, 8619342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; McGregor, H.C.; Short, M.A.; Zeng, H. Clinical utility of Raman spectroscopy: Current applications and ongoing developments. Adv. Health Care Technol. 2016, 2, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pence, I.; Mahadevan-Jansen, A. Clinical instrumentation and applications of Raman spectroscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1958–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourget, P.; Amin, A.; Vidal, F.; Merlette, C.; Lagarce, F. Comparison of Raman spectroscopy vs. high performance liquid chromatography for quality control of complex therapeutic objects: Model of elastomeric portable pumps filled with a fluorouracil solution. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 91, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bourget, P.; Amin, A.; Moriceau, A.; Cassard, B.; Vidal, F.; Clément, R. La Spectroscopie Raman (SR): Un nouvel outil adapté au contrôle de qualité analytique des préparations injectables en milieu de soins. Comparaison de la SR aux techniques CLHP et UV/visible-IRTF appliquée à la classe des anthracyclines en cancérologie. Pathol. Biol. 2012, 60, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lê, L.; Tfayli, A.; Zhou, J.; Prognon, P.; Baillet-Guffroy, A.; Caudron, E. Discrimination and quantification of two isomeric antineoplastic drugs by rapid and non-invasive analytical control using a handheld Raman spectrometer. Talanta 2016, 161, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Bourget, P.; Vidal, F.; Ader, F. Routine application of Raman spectroscopy in the quality control of hospital compounded ganciclovir. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 474, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, L.M.M.; Berge, M.; Tfayli, A.; Zhou, J.; Prognon, P.; Baillet-Guffroy, A.; Caudron, E. Rapid discrimination and quantification analysis of five antineoplastic drugs in aqueous solutions using Raman spectroscopy. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 111, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiehntopf, M.; Mönch, B.; Salzer, R.; Kupfer, M.; Hartmann, M. Quality control of cytotoxic drug preparations by means of Raman spectroscopy. Die Pharm. 2012, 67, 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lê, L.; Berge, M.; Tfayli, A.; Prognon, P.; Caudron, E. Discriminative and Quantitative Analysis of Antineoplastic Taxane Drugs Using a Handheld Raman Spectrometer. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8746729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makki, A.A.; Massot, V.; Byrne, H.J.; Respaud, R.; Bertrand, D.; Mohammed, E.; Chourpa, I.; Bonnier, F. Vibrational spectroscopy for discrimination and quantification of clinical chemotherapeutic preparations. Vib. Spectrosc. 2021, 113, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, A.A.; Bonnier, F.; Respaud, R.; Chtara, F.; Tfayli, A.; Tauber, C.; Bertrand, D.; Byrne, H.J.; Mohammed, E.; Chourpa, I. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of therapeutic solutions using Raman and infrared spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 218, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shorr, R.I.; Hoth, A.B.; Rawls, N. (Eds.) Drugs for the Geriatric Patient; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 930–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Drawz, S.M.; Bonomo, R.A. Three Decades of β-Lactamase Inhibitors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 160–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuriyama, T.; Karasawa, T.; Williams, D.W. Chapter Thirteen—Antimicrobial Chemotherapy: Significance to Healthcare. In Biofilms in Infection Prevention and Control; Percival, S.L., Williams, D.W., Randle, J., Cooper, T., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 209–244. [Google Scholar]

- Veni, P.R.K.; Sharmila, N.; Narayana, K.; Babu, B.H.; Satyanarayana, P. Simultaneous determination of piperacillin and tazobactam in pharmaceutical formulations by RP-HPLC method. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 7, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmakuri, L.R.; Krishna, K.; Kumar, C.H.; Raja, T.A. Simultaneous determination of piperacillin and tazobactum in bulk and pharmaceutical dosage forms by RP-HPLC. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 3, 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, P.; Rao, G.; Murthy, M.; Prathibha, H. Simultaneous estimation of piperacillin and tazobactam in injection formulations. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 68, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Council of Europe, European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Healthcare. European Pharmacopoeia 10.4; Council of Europe: Strasburg, France, 2020; p. 1168. [Google Scholar]

- Naicker, S.; Guerra Valero, Y.C.; Ordenez Meija, J.L.; Lipman, J.; Roberts, J.A.; Wallis, S.C.; Parker, S.L. A UHPLC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of piperacillin and tazobactam in plasma (total and unbound), urine and renal replacement therapy effluent. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 148, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zander, J.; Maier, B.; Suhr, A.; Zoller, M.; Frey, L.; Teupser, D.; Vogeser, M. Quantification of piperacillin, tazobactam, cefepime, meropenem, ciprofloxacin and linezolid in serum using an isotope dilution UHPLC-MS/MS method with semi-automated sample preparation. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2015, 53, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrisikou, I.; Orkoula, M.; Kontoyannis, C. FT-IR/ATR Solid Film Formation: Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of a Piperacillin-Tazobactam Formulation. Molecules 2020, 25, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpova, S.P.; Blazheyevskiy, M.; Mozgova, O. Development and validation of UV spectrophotometric area under curve method quantitative estimation of piperacillin. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2018, 9, 3556–3560. [Google Scholar]

- Toral, M.I.; Nova-Ramírez, F.; Nacaratte, F. Simultaneous determination of piperacillin and tazobactam in the pharmaceutical formulation Tazonam® by derivative spectrophotometry. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2012, 57, 1189–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Domes, C.; Domes, R.; Popp, J.; Pletz, M.W.; Frosch, T. Ultrasensitive Detection of Antiseptic Antibiotics in Aqueous Media and Human Urine Using Deep UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 9997–10003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamy, L.J.; Williams, R.L. 863. Infrared spectra and polar effects. Part VII. Dipolar effects in α-halogenated carbonyl compounds. J. Chem. Soc. (Resumed) 1957, 0, 4294–4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peesole, R.L.; Shields, L.D.; Cairus, T.; McWilliam, I.G. Modem Method of Chemicailanalysis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1976; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Volpin, M.E.; Koreshkov, Y.D.; Dulova, V.G.; Kursanov, D.N. Three-membered heteroaromatic compounds—I. Tetrahedron 1962, 18, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, A.; Savarianandam, A. IR and Laser Raman spectral analysis of dichlorodiphenylsulphone. Asian J. Phys. 1996, 5, 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, S.; Ilengovan, V. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Raman studies on 3-aminopyridine molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India 1995, 65, III. [Google Scholar]

- Boobyer, R.C. Intensities of C-H stretching modes for some small alicyclics. Spectrochim. Acta 1967, 23, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, S.; Tsuyama, H.; Tanaka, S.; Kamoda, H. Some considerations on the out-of-plane vibration bands of Phnx type molecules in the 800-670 cm−1 region in relation to the estimation of the twist angle θ of benzene rings from their intensities. Spectrochim. Acta 1974, 30, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalp, M.; Totir, M.A.; Buynak, J.D.; Carey, P.R. Different intermediate populations formed by tazobactam, sulbactam, and clavulanate reacting with SHV-1 beta-lactamases: Raman crystallographic evidence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2338–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heidari Torkabadi, H.; Che, T.; Shou, J.; Shanmugam, S.; Crowder, M.W.; Bonomo, R.A.; Pusztai-Carey, M.; Carey, P.R. Raman spectra of interchanging β-lactamase inhibitor intermediates on the millisecond time scale. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2895–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Skoog, D.A.; West, D.M.; Holler, F.J. Fundamentals of Analytical Chemistry, 6th ed.; Saunders, H.J.B., Ed.; Elsevier (Saunders): Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1991; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline Q2 (R1) Validation of Analytical Procedures. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-q2-r1-validation-analytical-procedures-text-methodology (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Miller, J.N.; Miller, J.C. Calibration methods: Regression and correlation. In Statistics and Chemometrics for Analytical Chemistry; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2005; pp. 107–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjiioannou, T.P.; Koupparis, Μ.A. Instrumental Analysis; University of Athens: Athens, Greece, 2005; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.J. Determination of the lower limit of detection. Clin. Chem. 1989, 35, 2152–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. Piperacillin, CID=43672. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Piperacillin (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. Tazobactam, CID=123630. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Tazobactam (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Bazin, C.; Cassard, B.; Caudron, E.; Prognon, P.; Havard, L. Comparative analysis of methods for real-time analytical control of chemotherapies preparations. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 494, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques, J.; Sousa, J.; Veiga, F.; Cardoso, C.; Vitorino, C. Process analytical technologies and injectable drug products: Is there a future? Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 554, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

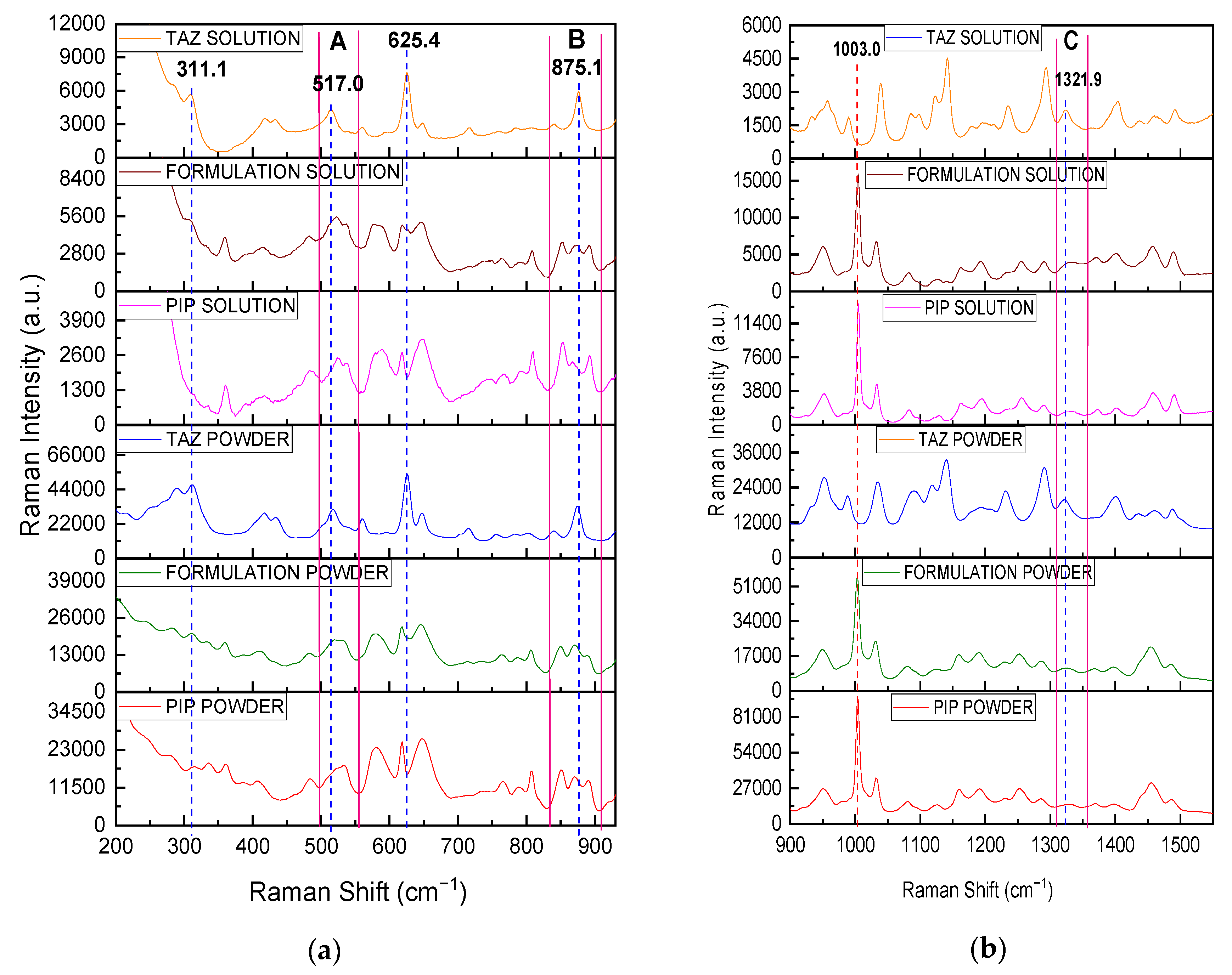

| API | Wavenumber (cm−1) | Vibration Mode |

|---|---|---|

| PIP | 406.0 | Carbonyl group (CO) bending |

| 890.0 | C-H bending | |

| 1003.0, 1032.0 | Aromatic C-C-C bending | |

| 1397.6 | N-H stretching | |

| 1456.0 | C-C stretching | |

| 1486.3 | N=H bending | |

| 1587.1, 1603.8, 1683.9 | C=C stretching | |

| TAZ | 625.4 | C-S stretching (Sulfone Ring) |

| 1231.1 | N=N stretching (Triazole Ring) | |

| 1290.4 | Triazole Ring Bending | |

| 1400.6 | CO2− stretching | |

| 1487.7 | C=C stretching (Triazole Ring) | |

| 1780.9 | Carbonyl group (CO) stretching |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Observation |

|---|---|

| 311.1 | Intensity enhancement (solid state)/ detection of TAZ peak (liquid state, in this case PIP peak is not detected at the certain position) |

| 517.0 | Intensity enhancement and change in the morphology of the broad PIP peak in area A |

| 625.4 | Detection of TAZ shoulder |

| 875.1 | Intensity enhancement and change in intensity ratio between neighboring PIP peaks in area B |

| 1321.9 | Intensity enhancement and shift of the relatively broad, weak PIP peak in area C |

| % Mass Ratio TAZ/PIP | I(517)/I(1003) | RSD% |

|---|---|---|

| 30:70 | 0.145 | 6.207 |

| 20:80 | 0.121 | 8.264 |

| 15:85 | 0.102 | 4.902 |

| 12.5:87.5 | 0.099 | 7.071 |

| 10:90 | 0.084 | 5.952 |

| API | C (mg/mL) | I(sample) − I(blank) (a.u.) | RSD% |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIP (1003.0 cm−1) | 266.67 | 29028.38 | 8.24 |

| 200.00 | 24576.15 | 9.16 | |

| 177.77 | 21479.97 | 6.90 | |

| 133.33 | 16696.92 | 6.62 | |

| 88.89 | 11867.34 | 8.07 | |

| 44.44 | 5848.70 | 8.78 | |

| 40.00 | 5654.34 | 8.77 | |

| 30.00 | 3981.94 | 4.11 | |

| 20.00 | 2634.56 | 3.81 | |

| 10.00 | 1350.39 | 4.60 | |

| 5.00 | 655.83 | 7.15 | |

| TAZ (311.1 cm−1) | 60.00 | 3001.38 | 6.93 |

| 50.00 | 2694.73 | 14.45 | |

| 40.00 | 2332.64 | 11.06 | |

| 33.33 | 2039.69 | 7.66 | |

| 25.00 | 1662.18 | 8.10 | |

| 22.22 | 1420.92 | 5.49 | |

| 16.67 | 1105.93 | 6.21 | |

| 11.11 | 840.31 | 10.09 | |

| 9.00 | 630.67 | 6.82 | |

| 7.00 | 494.35 | 9.46 |

| Focus Position | REMARKS |

|---|---|

| A or F | front quartz surface or back mirror surface, the peak is detectable but quite weak especially in case of position A |

| B or E | at a depth of 1 or 4 mm (very close to the front quartz or the back mirror surface), the peak signal is stronger than before but is not as strong as it could be |

| C | at a depth of 2 to 2.5 mm (approximately in the middle of the radiation path), the peak signal is close to its maximum value |

| D | at a depth of 4 mm (closer to the back mirror than to the front quartz surface), the peak signal is the maximum that could be obtained |

| API | C (mg/mL) | I(sample) − I(blank) (a.u.) | RSD% |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIP (1003.0 cm−1) | 44.44 | 13800.36 | 1.77 |

| 40.00 | 12062.34 | 1.60 | |

| 30.00 | 9463.25 | 0.80 | |

| 20.00 | 6354.26 | 0.75 | |

| 10.00 | 3084.76 | 1.51 | |

| 5.00 | 1561.74 | 1.66 | |

| TAZ (311.1 cm−1) | 5.56 | 899.10 | 5.47 |

| 5.00 | 761.14 | 9.22 | |

| 4.80 | 746.78 | 4.52 | |

| 4.20 | 626.54 | 4.08 | |

| 3.75 | 593.24 | 6.42 |

| Focus Position | REMARKS |

|---|---|

| A | outer front plastic surface, the peak is very weak |

| B | at a depth of 0.45 cm (close to the front plastic surface), the signal is stronger than before but not the maximum |

| C | at a depth of 0.9 to 1 cm (approximately in the middle of the radiation path), the peak signal is the maximum that could be obtained |

| D | at a depth of 1.35 cm (closer to the back than to the front plastic surface), the peak signal is close to its maximum value |

| E | at a depth larger than 1.60 cm (close to the back plastic surface), the signal is not as strong as it could be |

| C (mg/mL) | I(sample) − I(blank) (a.u.) | RSD% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIP | TAZ | 1003.0 cm−1 | 311.1 cm−1 | 1003.0 cm−1 | 311.1 cm−1 |

| 44.44 | 5.56 | 5708.64 | 349.73 | 2.00 | 5.77 |

| 40.00 | 5.00 | 5126.35 | 356.17 | 3.90 | 13.84 |

| 30.00 | 3.75 | 3905.66 | 185.09 | 2.69 | 26.59 |

| 20.00 | 2.50 | 2468.87 | 161.20 | 0.35 | 20.25 |

| 10.00 | 1.25 | 1298.05 | not detected | 1.38 | not detected |

| 5.00 | 0.62 | 583.98 | not detected | 4.99 | not detected |

| Method/ Container | Analysis Stage/ Nature/ Recording Time | Calibration Curve/Equation | LoD | Precision Control (Cunknown, Er) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Bottle | Before Reconstitution/ Non-invasive/ ≅10 min | Linear Curve/ = (0.192 ± 0.025)+ (−0.125 ± 0.029), (R2 = 0.953) | TAZ | PIP | TAZ | |

| 3.01% w/w | (90.17 ± 1.95)% w/w, 1.31% | (90.17 ± 1.95)% w/w, 1.31% | ||||

| After Reconstitution/ Non-invasive/ ≅10 min | PIP | Polynomial Curve / I1003(sample) − I1003(blank) = (−0.10 ± 0.02)*CPIP 2+ (138.94 ± 2.88)*CPIP + (−40.82 ± 31.46), (R2 = 0.999) | 0.60 mg/mL | (143.52 ± 10.52) mg/mL, 5.58% | ||

| (27.05 ± 2.02) mg/mL, 6.08% | ||||||

| TAZ | Polynomial Curve / I311(sample) − I311(blank) = ( −0.40 ± 0.06)*CTAZ2+ (73.99 ± 3.07)*CTAZ + (1.35 ± 28.86), (R2 = 0.997) | 1.85 mg/mL | (20.42 ± 1.42) mg/mL, 7.47% | |||

| (3.30 ± 0.75) mg/mL, 8.32% | ||||||

| Drip Chamber | Before Administration/ Non-invasive/ ≅5 min | PIP | I1003(sample) − I1003(blank) = (123.07±3.09)*CPIP + (17.76 ± 56.39), (R2 =0.997) | 0.41 mg/mL | (22.19 ± 1.04) mg/mL, 3.51% | |

| Raman Cell | Before Administration/ Invasive or not/ ≅5 min (3 repeats) Or ≅1.5 min (1 repeat) | PIP | I1003(sample) − I1003(blank) = (314.30 ± 3.81)*CPIP + (−8.38 ± 52.20), (R2 = 0.999) | 0.24 mg/mL | (22.46±0.60) mg/mL, 2.45% | |

| TAZ | I311(sample) − I311(blank) = (173.05 ± 19.13) *CTAZ + (−84.21 ± 85.82), (R2 = 0.965) | 0.94 mg/mL | (3.05±0.11) mg/mL, 6.27% | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chrisikou, I.; Orkoula, M.; Kontoyannis, C. Analysis of IV Drugs in the Hospital Workflow by Raman Spectroscopy: The Case of Piperacillin and Tazobactam. Molecules 2021, 26, 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26195879

Chrisikou I, Orkoula M, Kontoyannis C. Analysis of IV Drugs in the Hospital Workflow by Raman Spectroscopy: The Case of Piperacillin and Tazobactam. Molecules. 2021; 26(19):5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26195879

Chicago/Turabian StyleChrisikou, Ioanna, Malvina Orkoula, and Christos Kontoyannis. 2021. "Analysis of IV Drugs in the Hospital Workflow by Raman Spectroscopy: The Case of Piperacillin and Tazobactam" Molecules 26, no. 19: 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26195879

APA StyleChrisikou, I., Orkoula, M., & Kontoyannis, C. (2021). Analysis of IV Drugs in the Hospital Workflow by Raman Spectroscopy: The Case of Piperacillin and Tazobactam. Molecules, 26(19), 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26195879