The 115 Years Old Multicomponent Bargellini Reaction: Perspectives and New Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Discovery of a Novel Reaction

1.2. Guido Bargellini

2. The Bargellini Reaction

Reaction Mechanism and Formation of By-Products

3. Applications of Bargellini Reactions

3.1. Reaction with Phenols

3.2. Reaction with Other Nucleophiles

4. Applications of the Bargellini Reaction

5. The Future of Bargellini Reaction

- (a)

- substrate, acetone, CHCl3, freshly pulverized NaOH both at 0 °C, room temperature and at reflux;

- (b)

- substrate, acetone, CHCl3, freshly pulverized NaOH in THF both at 0 °C, room temperature and at reflux;

- (c)

- substrate, acetone, CHCl3, freshly pulverized NaOH 50% in water, dichloromethane, TEBAC under PTC at 0 °C

- (d)

- substrate, acetonechloroform (or related trichloromethylcarbinols), freshly pulverized NaOH, water, at 0 °C, room temperature and at reflux;

- (e)

- substrate, acetonechloroform (or related trichloromethylcarbinols), freshly pulverized NaOH, THF, at 0 °C, room temperature and at reflux;

- (f)

- acetonechloroform (or related trichloromethylcarbinols), freshly pulverized NaOH 50% in water, dichloromethane, TEBAC under PTC at 0 °C.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Link, B. Patent No. 28. R 665-D.R.P 80986, 1894.

- Schiff, H. Correspondenz aus Florenz. Ber. Deut. Chem. Ges. 1872, 5, 1055. [Google Scholar]

- Lustgarten, S. Über den Nachweis von Jodoform, Naphtol und Chloroform in thierischen Flüssigkeiten und Organen. Mon. für Chem. 1882, 3, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brieskorn, C.H.; Kallmayer, H.J. Reaktion des Resorcins mit Halogenmethanen unter alkalischen Bedingungen. Arch. Pharm. 1971, 304, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieskorn, C.H.; Kallmayer, H.J. Reaktionen der Naphthole mit Halogenmethanen unter alkalischen Bedingungen. Arch. Pharm. 1972, 305, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimer, K.; Ferd, T. Ueber die Einwirkung von Chloroform auf alkalische Phenolate. Chem. Ber. 1876, 9, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wynberg, H. The Reimer-Tiemann Reaction. Chem. Rev. 1960, 60, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustiniano, M.; Basso, A.; Mercalli, V.; Massarotti, A.; Novellino, E.; Tron, G.C.; Zhu, J. To Each his Own: Isonitriles for All Flavors. Functionalized Isocyanides as Valuable Tools in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1295–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargellini, G. Azione del Cloroformio e Idrato Sodico sui Fenoli in Soluzione nell’cetone. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1906, 36, 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Papeo, G. Pulici, Italian Chemists’ Contributions to Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis: An Historical Perspective. Molecules 2013, 18, 10870–10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bischoff, C.A. Studien über Verkettungen. XLIII. α-Phenoxy-Buttersäure, -Isobuttersäure und -Isovaleriansäure und deren Ester. Ber. Deut. Chem. Ges. 1900, 33, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wheland, R.; Bartlett, P.D. Alpha-Lactones from Diphenylketene and Di-tert-butylketene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 6057–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, G.D.; Williams, I.H. Oxiranones: α-lactones or zwitterions? Insights from calculated electron density distribution analysis. J. Chem Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 2001, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini-Bettolo, G.B. Necrologio. Chim. e l’Industria 1963, XLV, 1558–1559. [Google Scholar]

- Bargellini, G. 1,2,3-Trihydroxyflavone. Contribution to the knowledge of the constitution of scutellarein. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1919, 49, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bargellini, G. Fenilcumarine. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1925, 55, 945–951. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Bargellini Condensation. In Comprehensive Organic Name Reactions and Reagents; Wang, Z., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, W.; McKee, J.R.; Brown, R.; Lakshmanan, S.; McKee, G.A. Studies on the Rearrangement of (Trichloromethyl)carbinols to α-Chloroacetic Acids. Can. J. Chem. 1980, 58, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, E.J.; Link, J.O. A General, Catalytic, and Enantioselective Synthesis of α-Amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1192, 114, 1906–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, T.S. Recent Applications of Gem-Dichloroepoxide Intermediates in Synthesis. Arkivoc 2012, 2, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weizmann, C.H.; Sulzbacher, M.; Bergmann, E. The Synthesis of α-Alkoxyisobutyric Acids and Alkyl Methacrylates from Acetonechloroform. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, J. Carbon Dichloride as an Intermediate in the Basic Hydrolysis of Chloroform. A Mechanism for Substitution Reactions at a Saturated Carbon Atom. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 2438–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, R.A. “Carbon Dichloride”: Dihalocarbenes Sixty Years after Hine. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 5773–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcelli, L.; Gilardi, F.; Laghezza, A.; Piemontese, L.; Mitro, N.; Azzariti, A.; Altieri, F.; Cervoni, L.; Fracchiolla, G.; Giudici, M.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Evaluation of Ureidofibrate-Like Derivatives Endowed with Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.Z.; Kashmiri, M.A.; Ahmed, V.U.; Kazi, A.A.; Siddiqui, H.L. An Efficient Method for the Synthesis of Alkyl 2-(4-benzoylphenoxy)-2-methyl Propanoates. J. Chem. Soc. Pak. 2007, 29, 352–356. [Google Scholar]

- Merz, A.; Tomahogh, R. Zur Reaktion des Makosza-Reagens mit Aldehyden und Ketonen. Chem. Ber. 1977, 110, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.D.; Lach, J.L. The Kinetics of Degradation of Chlorobutanol. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 1959, 48, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanin, G.; Segre, G. Action of Alkaline Solutions on Trichloro Organic Compounds. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1911, 41, 671–674. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl, P.; Muhlstadt, M.; Graefe, J. Phasentransfer-katalysierte Reaktionen; Vl1. Synthese von 1-Chlorocyclohexancarbonsäure aus Cyclohexanon. Synthesis 1976, 12, 825–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henegar, K.E.; Lira, R. One-Pot in Situ Formation and Reaction of Trimethyl(trichloromethyl)silane: Application to the Synthesis of 2,2,2-Trichloromethylcarbinols. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 2999–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoek, F.H. The Kinetics of the Decomposition of the Trichloroacetates in Various Solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1934, 56, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetovich, R.J.; Chung, J.Y.L.; Kress, M.H.; Amato, J.S.; Matty, L.; Weingarten, M.D.; Tsay, F.-R.; Li, Z.; Zhou, G. An Efficient Synthesis of a Dual PPAR α/γ Agonist and the Formation of a Sterically Congested α-Aryloxyisobutyric Acid via a Bargellini Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 8560–8563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagan Nirmalan, K.; Ramalakshmi, N. Synthesis of Novel Phenoxy—Isobutyric Acid Derivatives, Reaction of Ketone under Bargellinic Reaction Conditions. Int. J. Chem. Tech. Res. 2015, 8, 1248–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti, P.; De Franceschi, A. Sintesi di Alcuni Derivati α-Isobutirrici. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1947, 77, 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, H.; Wilder, G.R. Some Substituted α-(Aryloxy)-isobutyric Acids and Amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 6644–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, M.; Baillarge, M.; Tchernoff, G. Sur Quelques nouveaux dérivés aryloxyisobutyriques et apparentés. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1956, 776–783. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R.D.; Fitzgerald, R.N.; Guo, J. Improved Method for the Synthesis of 2-Methyl-2-Aryloxypropanoic Acid Derivatives. Synthesis 2004, 12, 1959–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.E.; Davis, R.; Fitzgerald, R.N.; Haberman, J.M. Selective Phenol Alkylation: An Improved Preparation of Efaproxiral. Synth. Commun. 2006, 36, 2129–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.K.; Maghar, S.M.; Ganguly, S.N.; Pednekar, S.; Mandadi, A. Water-Based Biphasic Media for Exothermic Reactions: Green Chemistry Strategy for the Large Scale Preparation of Clofibric Acid and Analogues. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 3011–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banti, G. Azione del Cloretone e Potassa sulle Basi Aromatiche Primarie. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1929, 59, 819–824. [Google Scholar]

- Andreani, F.; Andrisano, R.; Andreani, A. New α-substituted aryl thioacetic derivatives forming analogues of clofibrate. Il Farmaco 1975, 30, 847–858. [Google Scholar]

- Melnikova, Y.V.; Lyakhov, A.S.; Ivashkevich, L.S.; Artamonova, T.V.; Novoselov, N.P.; Zevatskii, Y.E.; Myznikov, L.V. The Bargellini reaction in a series of Heterocyclic Thiols. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2016, 86, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, G.; Galimberti, P.; Melandri, M. Su Alcuni Derivati α-Isobutirrici. Boll. Chim. Farm. 1963, 102, 522–540. [Google Scholar]

- Buttini, A.; Galimberti, P.; Gerosa, V.; Melandri, M. Nuove Sintesi di Derivati Idantoinici. Boll. Chim. Farm. 1963, 102, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buttini, A.; Galimberti, P.; Gerosa, V. Nuova Sintesi di Derivati Tiazolidonici. Boll. Chim. Farm. 1963, 102, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buttini, A.; Melandri, M.; Galimberti, P. Introduzione del Radicale alfa-Isobutirrico su Semicarbazide, Tiosemicarbazide e Relativi 1 e 4 Fenilderivati. Ann. Chim. 1964, 54, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Melandri, M.; Buttini, G.; Gallo, G.; Pasqualucci, C.R. New Synthesis of the Glycocyamidine Group. Ann. Chim. 1966, 56, 1259–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.T. Hindered Amines. Novel Synthesis of 1,3,3,5,5-Pentasubstitued 2-Piperazinones. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanine, T.A.; Stokes, S.; Scott, J.S. Synthesis of Electron-Deficient N1-(Hetero)aryl 3,3,5,5-Tetramethyl Piperazinones. Synlett 2017, 28, 357–361. [Google Scholar]

- Rychnovsky, S.D.; Beauchamp, T.; Vaidyanathan, R.; Kwan, T. Synthesis of Chiral Nitroxides and an Unusual Racemization Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 6363–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesvadba, P. Radicals and Polymers. Chimia 2018, 72, 456–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesvadba, P.; Kramer, A.; Zink, M.-O. Heterocyclic Alkoxyamine Polymerization Composition Useful as Regulator in Free-Radical Polymerization to Obtain Low-Polydispersity Polymeric Resins. German Patent DE19949352A1, 20 April 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.T. Hindered Amines. 2. Synthesis of Hindered Acyclic α-Aminoacetamides. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 3671–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanine, T.A.; Stokes, S.; Scott, J.S. Practical Synthesis of 3,3-Substituted Dihydroquinoxalin-2-ones from Aryl 1,2-Diamines using the Bargellini Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 4386–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, T.; Hansen, J.H. 3,4-Dihydroquinoxalin-2-ones: Recent Advances in Synthesis and Bioactivities (microreview). Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2017, 53, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, J.T. Totally Hindered Phenols. 2,6-Di-t-butyl-4-(1,1-dialkyl-1-acetamide)-phenols and their Persistent Phenoxy Radicals. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

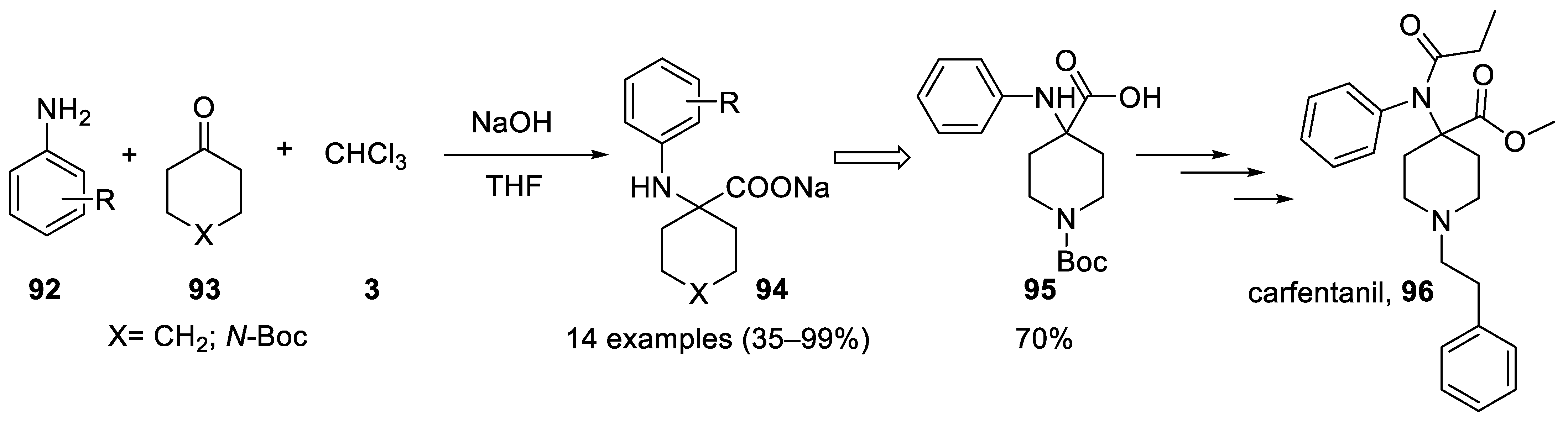

- Butcher, K.J.; Hurst, J. Aromatic Amines as Nucleophiles in the Bargellini Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 2497–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohman, M.d.R.; Myrboh, B. KF-Alumina-Mediated Bargellini Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 4772–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Asadi, M.; Saeedi, M.; Rezaei, Z.; Moghbel, H.; Foroumadi, A.; Shafiee, A. Synthesis of Novel 1,4-Benzodiazepine-3,5-dione Derivatives: Reaction of 2-Aminobenzamides under Bargellini Reaction Conditions. Synlett 2012, 23, 2521–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryanasab, F.; Saidi, M.R. Dithiocarbamic Acids and Thiols as Nucleophiles in the Bargellini Reaction. Sci. Iran. 2012, 19, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rashid, Z.; Ghahremanzadeh, R.; Naeimi, H. Bargellini Condensation of Ninhydrin as a Ketone and Substituted Anilines as Nucleophiles. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 1962–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korger, G. Über die Synthese von Grisanonen-(3). Chem. Ber. 1963, 96, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhina, K.; Bhowmik, D.R.; Venkateswaran, R.V. Formal Syntheses of Heliannuols A and D, Allelochemicals from Helianthus annus. Chem. Commun. 2002, 6, 634–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Tuhina, K.; Bhowmik, D.P.; Venkateswaran, R.V. Synthesis of Heliannuols A and K, Allelochemicals from Cultivar Sunflowers and the Marine Metabolite Heliane, Unusual Sesquiterpene Containing a Benzoxocane Ring System. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Sen, P.K.; Roy, A. Synthesis of (±)-heliannuol C. Synth. Commun. 2017, 47, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Du, Z.; Tao, Z. Total Syntheses of Heliannuols: An Overview. Synth. Commun. 2015, 45, 663–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartieri, F.; Mesiano, L.E.; Borghi, D.; Desperati, V.; Gennari, C.; Papeo, G. Total Synthesis of (+)-7,11-Helianane and (+)-5-Chloro-7,11-helianane through Stereoselective Aromatic Claisen Rearrangement. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 6794–6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.P.; Biswas, B.; Venkateswaran, R.V. Bargellini Condensation of Coumarins. Expeditious Synthesis of o-Carboxyvinylphenoxyisobutyric Acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 8741–8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, E.J.; Barcza, S.; Klotmann, G. Directed Conversion of the Phenoxy Grouping into a Variety of Cyclic Polyfunctional Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 4782–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustiniano, M.; Pelliccia, S.; Galli, U.; Amato, J.; Travagin, F.; Novellino, E.; Tron, G.C. A Successful Replacement of Phenols with Isocyanides in the Bargellini Reaction: Synthesis of 3-Carboxamido-Isobutyric Acids. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 11467–11471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farhid, H.; Nazeri, M.T.; Shaabani, A.; Armaghan, M.; Janiak, C. Isocyanide-based Consecutive Bargellini/Ugi Reactions: An Efficient Method for the Synthesis of Pseudo-peptides Containing Three Amide Bonds. Amino Acids 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talele, T.T. Natural-Products-inspired Use of the Gem-dimethyl Group in Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2166–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, D.; Roy, A.; Seibel, W.L.; West, L.; Portlock, D.E. The Synthesis of Aza-β-lactams via Tandem Petasis–Ugi Multi-component Condensation and 1,3-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) Condensation Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 6297–6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portlock, D.E.; Ostaszewski, R.; Naskar, D.; West, L. A Tandem Petasis–Ugi Multi Component Condensation Reaction: Solution Phase Synthesis of Six Dimensional Libraries. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serafini, M.; Murgia, I.; Giustiniano, M.; Pirali, T.; Tron, G.C. The 115 Years Old Multicomponent Bargellini Reaction: Perspectives and New Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26030558

Serafini M, Murgia I, Giustiniano M, Pirali T, Tron GC. The 115 Years Old Multicomponent Bargellini Reaction: Perspectives and New Applications. Molecules. 2021; 26(3):558. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26030558

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerafini, Marta, Ilaria Murgia, Mariateresa Giustiniano, Tracey Pirali, and Gian Cesare Tron. 2021. "The 115 Years Old Multicomponent Bargellini Reaction: Perspectives and New Applications" Molecules 26, no. 3: 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26030558