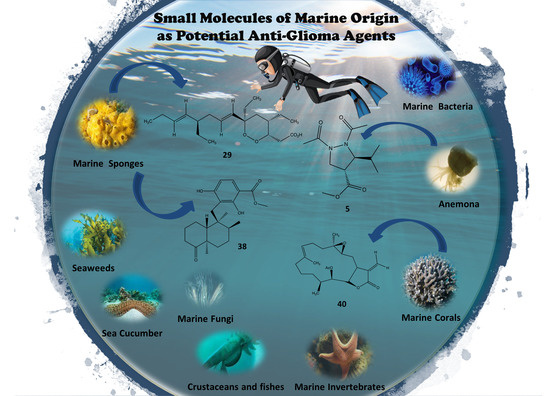

Small Molecules of Marine Origin as Potential Anti-Glioma Agents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Treatment of Glioma

3. Marine Organisms as Sources of Anti-Glioma Compounds

3.1. Marine Anemone

3.2. Seaweed

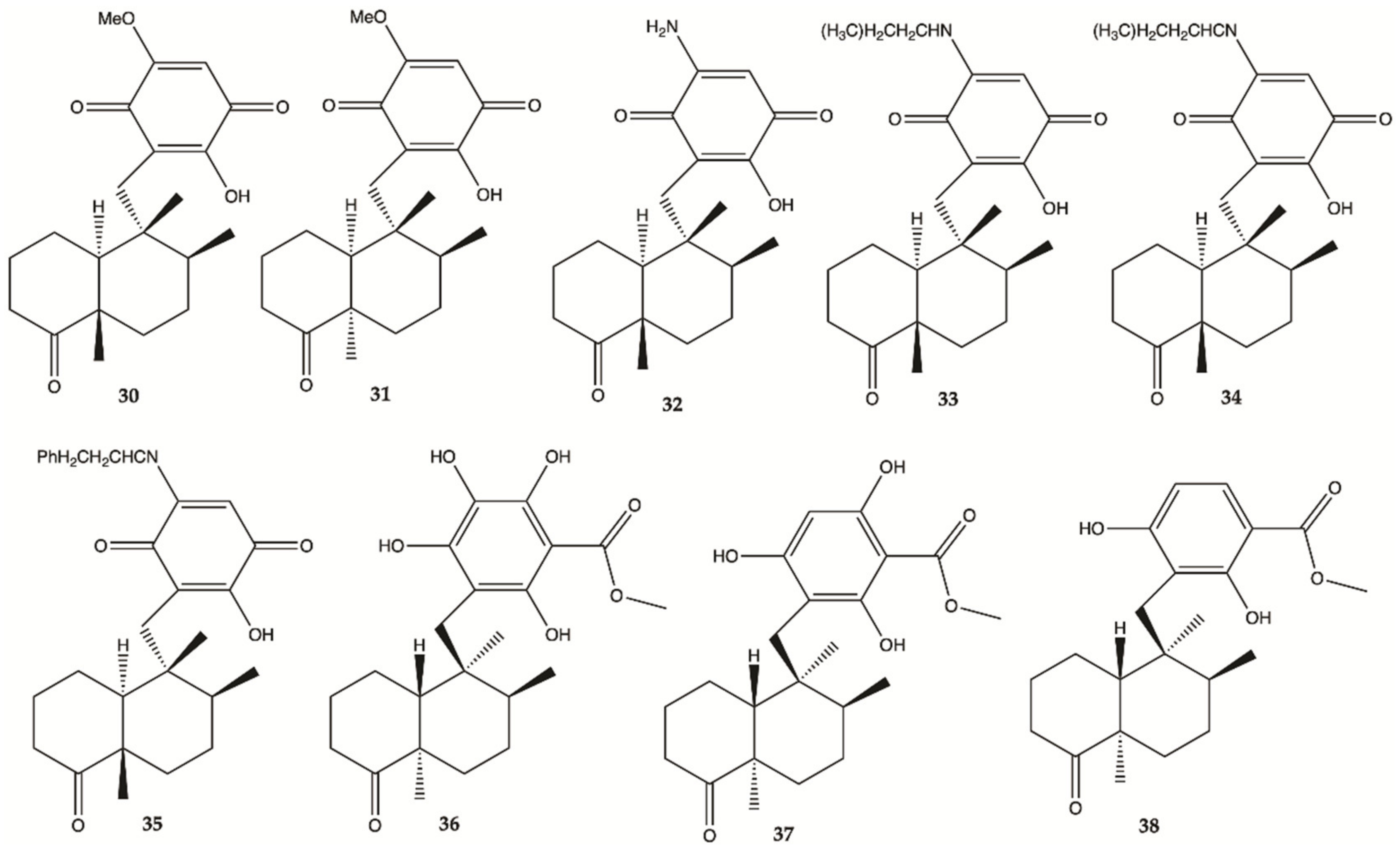

3.2.1. Red Seaweeds

3.2.2. Brown Seaweeds

3.2.3. Green Seaweeds

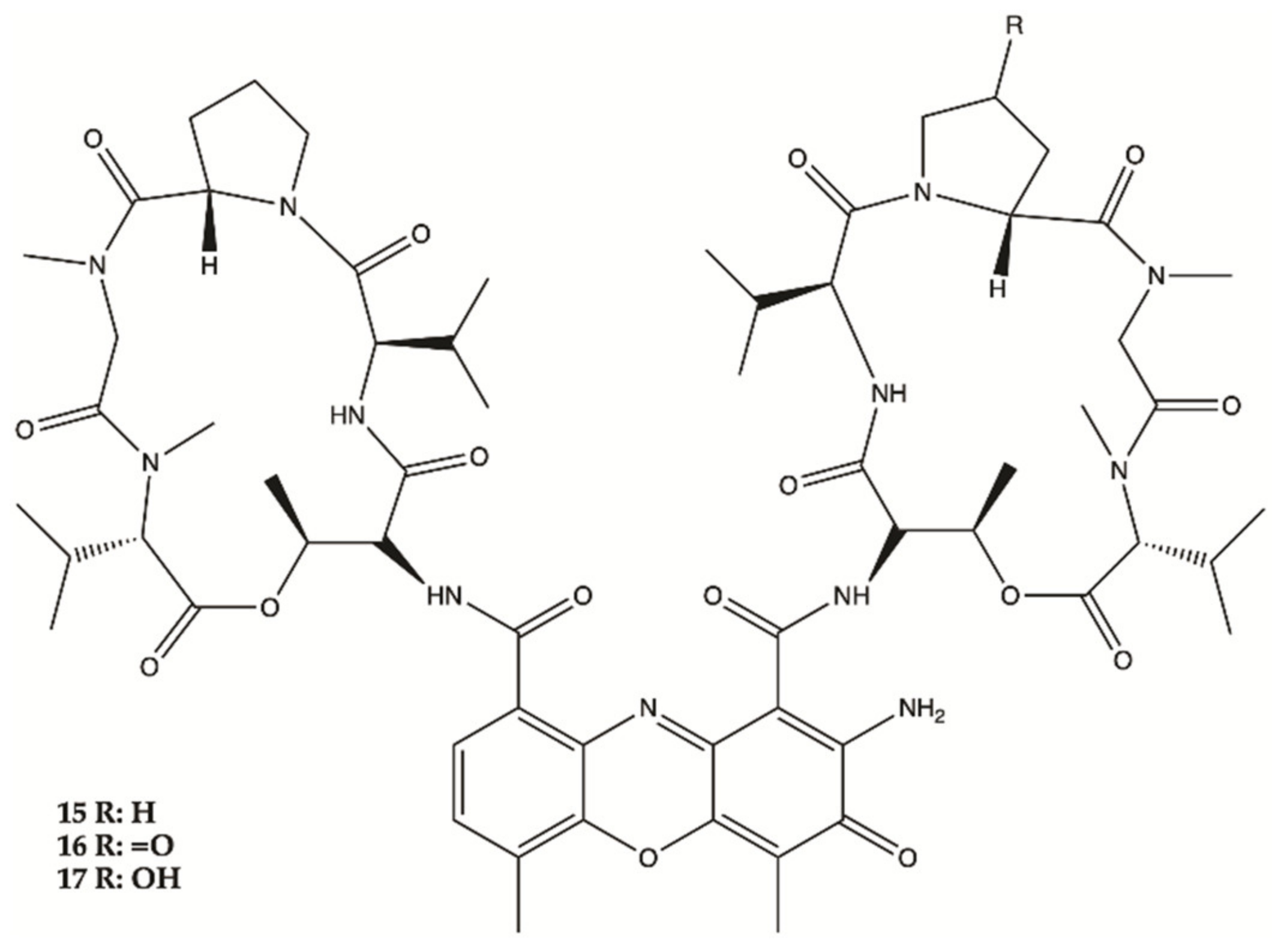

3.3. Marine Bacteria

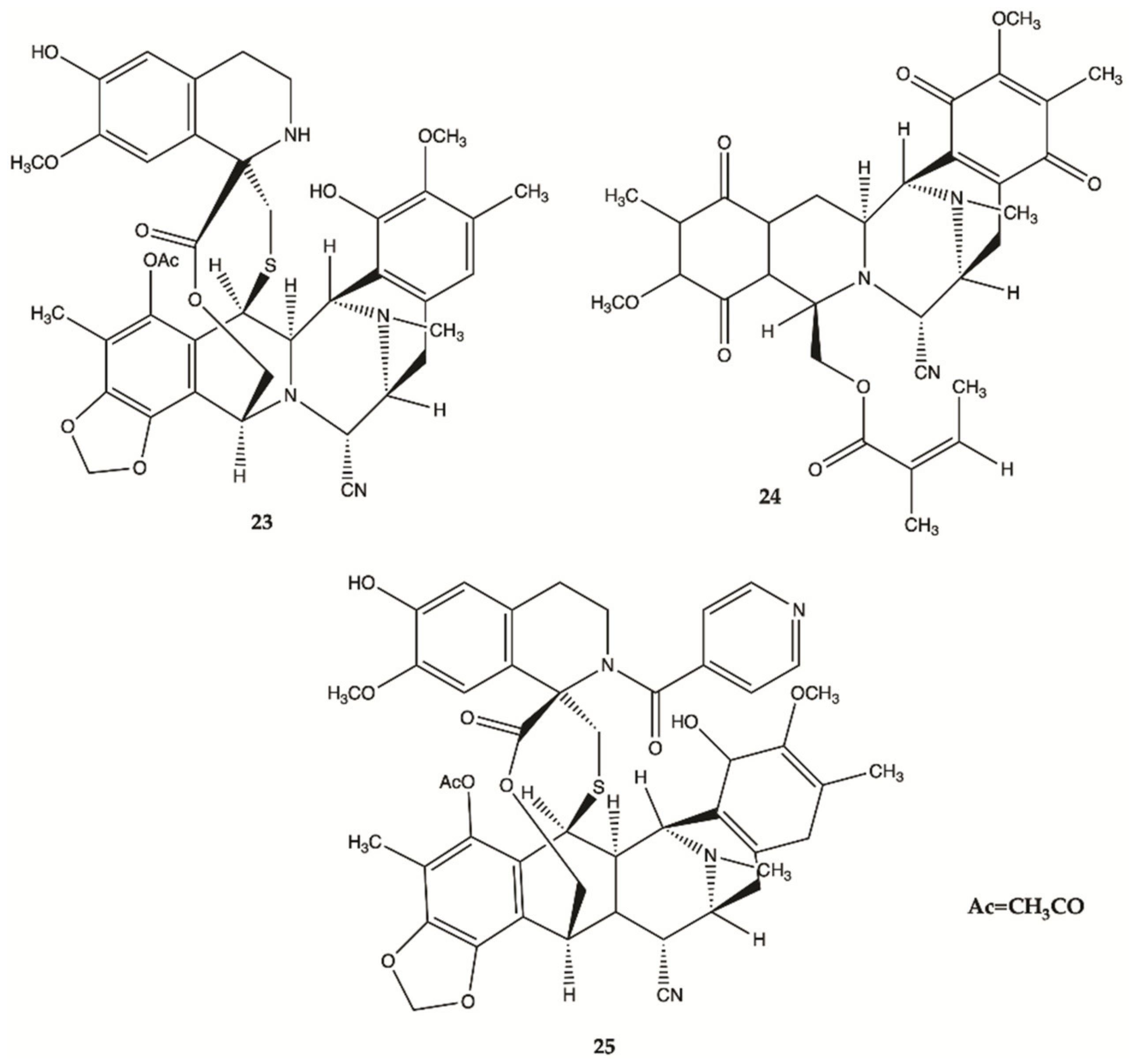

3.4. Marine Invertebrates

3.5. Marine Sponges

3.6. Marine Corals

3.7. Marine Fungi

3.8. Cucumbers

3.9. Crustaceans and Fishes

4. ADME Properties

| Compounds | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | LogP | H-Bond Acceptors-Donors 10-5 | Lipinsky Rules | BBB Permeability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 298.25 | 1.32 | 6-3 | Yes | No |

| 2 | 304.29 | 2.01 | 6-2 | Yes | No |

| 3 | 329.35 | 1.65 | 6-4 | Yes | No |

| 4 | 228.25 | 1.25 | 4-1 | Yes | No |

| 5 | 254.33 | 2.70 | 3-0 | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | 168.19 | 1.76 | 2-0 | Yes | No |

| 7 | 299.29 | 3.61 | 0-0 | No | No |

| 8 | 372.28 | 1.78 | 9-6 | No | No |

| 9 | 242.25 | 0.58 | 7-3 | Yes | No |

| 10 | 644.92 | 6.73 | 5-2 | No | No |

| 11 | 610.78 | 4.43 | 10-5 | No | No |

| 12 | 604.81 | 5.00 | 8-3 | No | No |

| 13 | 620.81 | 4.74 | 9-4 | No | No |

| 14 | 674.90 | 5.89 | 9-2 | No | No |

| 15 | 1243.45 | 5.80 | 18-5 | No | No |

| 16 | 1258.44 | −0.33 | 19-5 | No | No |

| 17 | 1259.45 | 5.14 | 19-6 | No | No |

| 18 | 748.77 | 4.27 | 14-5 | No | No |

| 19 | 734.74 | 4.23 | 14-6 | No | No |

| 20 | 297.35 | 1.55 | 5-3 | Yes | No |

| 21 | 297.35 | 1.53 | 5-3 | Yes | No |

| 22 | 298.29 | 2.26 | 5-3 | Yes | No |

| 23 | 769.92 | 0.00 | 11-4 | No | No |

| 24 | 579.64 | 0.00 | 11-0 | No | No |

| 25 | 889.03 | 1.43 | 10-1 | No | No |

| 26 | 436.6 | 4.46 | 2-2 | No | No |

| 27 | 464.73 | 4.49 | 3-1 | No | Yes |

| 28 | 426.72 | 4.85 | 2-2 | No | No |

| 29 | 338.48 | 3.83 | 4-1 | Yes | Yes |

| 30 | 360.44 | 2.91 | 5-1 | Yes | No |

| 31 | 360.44 | 2.72 | 5-1 | Yes | No |

| 32 | 345.43 | 2.15 | 4-2 | Yes | No |

| 33 | 401.54 | 3.51 | 4-2 | Yes | No |

| 34 | 415.57 | 3.67 | 4-2 | Yes | No |

| 35 | 449.58 | 3.67 | 4-2 | Yes | No |

| 36 | 392.49 | 2.45 | 6-3 | Yes | No |

| 37 | 376.49 | 2.48 | 5-2 | Yes | No |

| 38 | 360.49 | 3.06 | 4-1 | Yes | Yes |

| 39 | 315.49 | 3.88 | 4-4 | Yes | No |

| 40 | 376.49 | 3.30 | 5-0 | Yes | Yes |

| 41 | 378.50 | 3.31 | 5-1 | Yes | Yes |

| 42 | 516.62 | 4.29 | 8-2 | No | No |

| 43 | 318.45 | 3.31 | 3-1 | Yes | Yes |

| 44 | 332.48 | 3.63 | 3-0 | Yes | Yes |

| 45 | 330.46 | 3.00 | 3-0 | Yes | Yes |

| 46 | 374.51 | 4.07 | 4-0 | No | Yes |

| 47 | 517.66 | 3.41 | 5-2 | No | No |

| 48 | 925.99 | 0.00 | 19-6 | No | No |

| 49 | 1221.30 | 4.52 | 20-7 | No | No |

| 50 | 882.98 | 0.00 | 17-6 | No | No |

| 51 | 568.79 | 6.14 | 4-2 | No | No |

| 52 | 582.85 | 6.83 | 3-2 | No | No |

| TMZ | 194.15 | 1.29 | 5-1 | Yes | No |

5. Nanotechnology to Improve Anti-Glioblastoma Drugs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Poon, M.T.C.; Sudlow, C.L.M.; Figueroa, J.D.; Brennan, P.M. Longer-term (≥2 years) survival in patients with glioblastoma in population-based studies pre- and post-2005: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanif, F.; Muzaffar, K.; Perveen, K.; Malhi, S.M.; Simjee, S.U. Glioblastoma Multiforme: A Review of its Epidemiology and Pathogenesis through Clinical Presentation and Treatment. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svec, R.L.; Furiassi, L.; Skibinski, C.G.; Fan, T.M.; Riggins, G.J.; Hergenrother, P.J. Tunable Stability of Imidazotetrazines Leads to a Potent Compound for Glioblastoma. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 3206–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martins, S.M.; Sarmento, B.; Nunes, C.; Lucio, M.; Reis, S.; Ferreira, D.C. Brain targeting effect of camptothecin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles in rat after intravenous administration. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. Off. J. Arbeitsgem. Pharm. Verfahrenstech. e.V. 2013, 85, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira de Castro, J.; Gomes, E.D.; Granja, S.; Anjo, S.I.; Baltazar, F.; Manadas, B.; Salgado, A.J.; Costa, B.M. Impact of mesenchymal stem cells’ secretome on glioblastoma pathophysiology. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, C.S.; Vieira de Castro, J.; Pojo, M.; Martins, E.P.; Queiros, S.; Chautard, E.; Taipa, R.; Pires, M.M.; Pinto, A.A.; Pardal, F.; et al. WNT6 is a novel oncogenic prognostic biomarker in human glioblastoma. Theranostics 2018, 8, 4805–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrugala, M.M. Advances and challenges in the treatment of glioblastoma: A clinician’s perspective. Discov. Med. 2013, 15, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Weng, X.; Lei, H.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, J.; Lu, W.; Wei, X.; et al. Two-order targeted brain tumor imaging by using an optical/paramagnetic nanoprobe across the blood brain barrier. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, D.A.; Wen, P.Y. Therapeutic advances in the treatment of glioblastoma: Rationale and potential role of targeted agents. Oncologist 2006, 11, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moody, C.L.; Wheelhouse, R.T. The medicinal chemistry of imidazotetrazine prodrugs. Pharmaceuticals 2014, 7, 797–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, J.; Tsai, Y.Y.; Chinnaiyan, P.; Yu, H.H. Effectiveness of radiotherapy for elderly patients with glioblastoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 81, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.E.; Khuntia, D.; Robins, H.I.; Mehta, M.P. Radiotherapy and radiosensitizers in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 2007, 5, 894–902. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, C.; Vaz, A.R.; Oliveira, M.C.; Matilde Marques, M.; Moreira, R.; Brites, D.; Perry, M.J. Targeting gliomas with triazene-based hybrids: Structure-activity relationship, mechanistic study and stability. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 172, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, X.; He, L.; Zhu, Y. Computer-aided design of temozolomide derivatives based on alkylglycerone phosphate synthase structure with isothiocyanate and their pharmacokinetic/toxicity prediction and anti-tumor activity in vitro. Biomed. Rep. 2018, 8, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, Z.; Wei, D.; Dai, X.; Stevens, M.F.G.; Bradshaw, T.D.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, J. C8-Substituted Imidazotetrazine Analogs Overcome Temozolomide Resistance by Inducing DNA Adducts and DNA Damage. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.F.d.S.; Fernandes, B.C.; Valente, V.; dos Santos, J.L. Recent advances in the discovery of small molecules targeting glioblastoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 164, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filbin, M.G.; Dabral, S.K.; Pazyra-Murphy, M.F.; Ramkissoon, S.; Kung, A.L.; Pak, E.; Chung, J.; Theisen, M.A.; Sun, Y.; Franchetti, Y.; et al. Coordinate activation of Shh and PI3K signaling in PTEN-deficient glioblastoma: New therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1518–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abeyrathna, P.; Su, Y. The critical role of Akt in cardiovascular function. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2015, 74, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beyer, C.F.; Zhang, N.; Hernandez, R.; Vitale, D.; Lucas, J.; Nguyen, T.; Discafani, C.; Ayral-Kaloustian, S.; Gibbons, J.J. TTI-237: A novel microtubule-active compound with in vivo antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 2292–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kitambi, S.S.; Toledo, E.M.; Usoskin, D.; Wee, S.; Harisankar, A.; Svensson, R.; Sigmundsson, K.; Kalderén, C.; Niklasson, M.; Kundu, S.; et al. RETRACTED: Vulnerability of Glioblastoma Cells to Catastrophic Vacuolization and Death Induced by a Small Molecule. Cell 2014, 157, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sestito, S.; Daniele, S.; Nesi, G.; Zappelli, E.; Di Maio, D.; Marinelli, L.; Digiacomo, M.; Lapucci, A.; Martini, C.; Novellino, E.; et al. Locking PDK1 in DFG-out conformation through 2-oxo-indole containing molecules: Another tools to fight glioblastoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 118, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, A.E.; Haas, B.R.; Naydenov, A.V.; Fung, S.; Xu, C.; Swinney, K.; Wagenbach, M.; Freeling, J.; Canton, D.A.; Coy, J.; et al. ST-11: A New Brain-Penetrant Microtubule-Destabilizing Agent with Therapeutic Potential for Glioblastoma Multiforme. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 2018–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Overmeyer, J.H.; Young, A.M.; Bhanot, H.; Maltese, W.A. A chalcone-related small molecule that induces methuosis, a novel form of non-apoptotic cell death, in glioblastoma cells. Mol. Cancer 2011, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robinson, M.W.; Overmeyer, J.H.; Young, A.M.; Erhardt, P.W.; Maltese, W.A. Synthesis and evaluation of indole-based chalcones as inducers of methuosis, a novel type of nonapoptotic cell death. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1940–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sestito, S.; Nesi, G.; Daniele, S.; Martelli, A.; Digiacomo, M.; Borghini, A.; Pietra, D.; Calderone, V.; Lapucci, A.; Falasca, M.; et al. Design and synthesis of 2-oxindole based multi-targeted inhibitors of PDK1/Akt signaling pathway for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 105, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele, S.; Sestito, S.; Pietrobono, D.; Giacomelli, C.; Chiellini, G.; Di Maio, D.; Marinelli, L.; Novellino, E.; Martini, C.; Rapposelli, S. Dual Inhibition of PDK1 and Aurora Kinase A: An Effective Strategy to Induce Differentiation and Apoptosis of Human Glioblastoma Multiforme Stem Cells. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, R.; Pérez-Correa, J.R.; Domínguez, H. Bioactive Properties of Marine Phenolics. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stien, D. Marine Microbial Diversity as a Source of Bioactive Natural Products. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.T.; Correia da Silva, M.; Pinto, M.; Cidade, H.; Kijjoa, A. Marine natural flavonoids: Chemistry and biological activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 3260–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleria, H.A.R.; Gobe, G.; Masci, P.; Osborne, S.A. Marine bioactive compounds and health promoting perspectives; innovation pathways for drug discovery. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.R.; Copp, B.R.; Davis, R.A.; Keyzers, R.A.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021, 38, 362–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honek, J.; Efferth, T. Marine Compounds. In Biodiversity, Natural Products and Cancer Treatment; World Scientific: Singapore, 2013; pp. 209–250. [Google Scholar]

- Wali, A.F.; Majid, S.; Rasool, S.; Shehada, S.B.; Abdulkareem, S.K.; Firdous, A.; Beigh, S.; Shakeel, S.; Mushtaq, S.; Akbar, I.; et al. Natural products against cancer: Review on phytochemicals from marine sources in preventing cancer. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Torres, V.; Encinar, J.A.; Herranz-López, M.; Pérez-Sánchez, A.; Galiano, V.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Micol, V. An Updated Review on Marine Anticancer Compounds: The Use of Virtual Screening for the Discovery of Small-Molecule Cancer Drugs. Molecules 2017, 22, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, X.; Chai, W.; Lian, X.-Y.; Zhang, Z. New Metabolites and Bioactive Actinomycins from Marine-Derived Streptomyces sp. ZZ338. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ye, X.; Anjum, K.; Song, T.; Wang, W.; Liang, Y.; Chen, M.; Huang, H.; Lian, X.-Y.; Zhang, Z. Antiproliferative cyclodepsipeptides from the marine actinomycete Streptomyces sp. P11-23B downregulating the tumor metabolic enzymes of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and lipogenesis. Phytochemistry 2017, 135, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, K.; Bi, H.; Chai, W.; Lian, X.-Y.; Zhang, Z. Antiglioma pseurotin A from marine Bacillus sp. FS8D regulating tumour metabolic enzymes. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chai, W.; Song, T.; Ma, M.; Lian, X.-Y.; Zhang, Z. Anti-glioma Natural Products Downregulating Tumor Glycolytic Enzymes from Marine Actinomycete Streptomyces sp. ZZ406. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyun, K.H.; Yoon, C.H.; Kim, R.K.; Lim, E.J.; An, S.; Park, M.J.; Hyun, J.W.; Suh, Y.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, S.J. Eckol suppresses maintenance of stemness and malignancies in glioma stem-like cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 254, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.R.; Hosokawa, M.; Miyashita, K. Fucoxanthin: A marine carotenoid exerting anti-cancer effects by affecting multiple mechanisms. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 5130–5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Anjum, K.; Chen, L.; Lian, X.Y. Bioactive Bafilomycins and a New N-Arylpyrazinone Derivative from Marine-derived Streptomyces sp. HZP-2216E. Planta Med. 2017, 83, 1405–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gong, A.; Guo, P.; Gong, L.; Liang, H. Aplysin suppresses the invasion of glioma cells by targeting Akt pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 9, 8062–8068. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Song, Q.; Shao, Q.; Gao, W.; Mao, H.; Lou, H.; Qu, X.; Li, X. Comparison of the effects of marchantin C and fucoidan on sFlt-1 and angiogenesis in glioma microenvironment. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengarajan, T.; Rajendran, P.; Nandakumar, N.; Balasubramanian, M.P.; Nishigaki, I. Cancer preventive efficacy of marine carotenoid fucoxanthin: Cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Nutrients 2013, 5, 4978–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xin, W.; Ye, X.; Yu, S.; Lian, X.Y.; Zhang, Z. New capoamycin-type antibiotics and polyene acids from marine Streptomyces fradiae PTZ0025. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 2388–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.; Yi, W.W.; Ge, H.J.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Wu, B. Bioactive Streptoglutarimides A-J from the Marine-Derived Streptomyces sp. ZZ741. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 2800–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wätjen, W.; Ebada, S.; Bergermann, A.; Chovolou, Y.; Totzke, F.; Kubbutat, M.; Lin, W.; Chaidir, C. Cytotoxic effects of the anthraquinone derivatives 1′-deoxyrhodoptilometrin and (S)-(−)-rhodoptilometrin isolated from the marine echinoderm Comanthus sp. Arch. Toxicol. 2016, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabunoki, H.; Saito, N.; Suwanborirux, K.; Charupant, K.; Satoh, J.-I. Molecular network profiling of U373MG human glioblastoma cells following induction of apoptosis by novel marine-derived anti-cancer 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids. Cancer Cell Int. 2012, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borbone, N.; De Marino, S.; Iorizzi, M.; Zollo, F.; Debitus, C.; Esposito, G.; Iuvone, T. Minor steroidal alkaloids from the marine sponge Corticium sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1206–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamaru, A.; Iwado, E.; Kondo, S.; Newman, R.A.; Vera, B.; Rodriguez, A.D.; Kondo, Y. Eupalmerin acetate, a novel anticancer agent from Caribbean gorgonian octocorals, induces apoptosis in malignant glioma cells via the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathway. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neupane, R.P.; Parrish, S.M.; Neupane, J.B.; Yoshida, W.Y.; Yip, M.L.R.; Turkson, J.; Harper, M.K.; Head, J.D.; Williams, P.G. Cytotoxic Sesquiterpenoid Quinones and Quinols, and an 11-Membered Heterocycle, Kauamide, from the Hawaiian Marine Sponge Dactylospongia elegans. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biegelmeyer, R.; Schröder, R.; Rambo, D.F.; Dresch, R.R.; Carraro, J.L.F.; Mothes, B.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Junior, M.L.C.d.F.; Henriques, A.T. Sphingosines Derived from Marine Sponge as Potential Multi-Target Drug Related to Disorders in Cancer Development. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5552–5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Chen, M.; Chai, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lian, X.-Y. New bioactive pyrrospirones C−I from a marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. ZZ380. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ye, X.; Huang, H.; Peng, R.; Su, Z.; Lian, X.Y.; Zhang, Z. Bioactive sulfated saponins from sea cucumber Holothuria moebii. Planta Med. 2015, 81, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsuji, S.; Nakamura, S.; Maoka, T.; Yamada, T.; Imai, T.; Ohba, T.; Yako, T.; Hayashi, M.; Endo, K.; Saio, M.; et al. Antitumour Effects of Astaxanthin and Adonixanthin on Glioblastoma. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, M.; Resende, D.I.S.P.; Durães, F.; Pinto, M.M.M.; Sousa, E. Xanthenes in Medicinal Chemistry—Synthetic strategies and biological activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 113085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loureiro, D.R.P.; Magalhães, Á.F.; Soares, J.X.; Pinto, J.; Azevedo, C.M.G.; Vieira, S.; Henriques, A.; Ferreira, H.; Neves, N.; Bousbaa, H.; et al. Yicathins B and C and Analogues: Total Synthesis, Lipophilicity and Biological Activities. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, B.S.; AlAmri, A.H.; McConville, C. Polymeric Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Malignant Gliomas. Cancers 2020, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Aquino, R. Good Drug Therapy: It’s Not Just the Molecule—It’s the Delivery. Chem. Eng. Progress 2004, 100, 15S–17S. [Google Scholar]

- Re, F.; Gregori, M.; Masserini, M. Nanotechnology for neurodegenerative disorders. Maturitas 2012, 73, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjua, T.I.; Rewatkar, P.; Ahmed-Cox, A.; Saeed, I.; Mansfeld, F.M.; Kulshreshtha, R.; Kumeria, T.; Ziegler, D.S.; Kavallaris, M.; Mazzieri, R.; et al. Frontiers in the treatment of glioblastoma: Past, present and emerging. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 171, 108–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, S.; Md, S.; Alam, M.I.; Sahni, J.K.; Ali, J.; Baboota, S. Nanostructure-based drug delivery systems for brain targeting. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2012, 38, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicki, A.; Witzigmann, D.; Balasubramanian, V.; Huwyler, J. Nanomedicine in cancer therapy: Challenges, opportunities, and clinical applications. J. Control. Release 2015, 200, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alphandery, E. Nano-Therapies for Glioblastoma Treatment. Cancers 2020, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lam, F.C.; Morton, S.W.; Wyckoff, J.; Vu Han, T.-L.; Hwang, M.K.; Maffa, A.; Balkanska-Sinclair, E.; Yaffe, M.B.; Floyd, S.R.; Hammond, P.T. Enhanced efficacy of combined temozolomide and bromodomain inhibitor therapy for gliomas using targeted nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Wang, K.; Stephen, Z.R.; Mu, Q.; Kievit, F.M.; Chiu, D.T.; Press, O.W.; Zhang, M. Temozolomide nanoparticles for targeted glioblastoma therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6674–6682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramalho, M.J.; Sevin, E.; Gosselet, F.; Lima, J.; Coelho, M.A.N.; Loureiro, J.A.; Pereira, M.C. Receptor-mediated PLGA nanoparticles for glioblastoma multiforme treatment. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 545, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertucci, A.; Prasetyanto, E.A.; Septiadi, D.; Manicardi, A.; Brognara, E.; Gambari, R.; Corradini, R.; De Cola, L. Combined Delivery of Temozolomide and Anti-miR221 PNA Using Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Induces Apoptosis in Resistant Glioma Cells. Small 2015, 11, 5687–5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, M.; Mir Mohamad Sadeghi, G.; Haririan, I. A novel biocompatible drug delivery system of chitosan/temozolomide nanoparticles loaded PCL-PU nanofibers for sustained delivery of temozolomide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 97, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürten, B.; Yenigül, E.; Sezer, A.D.; Altan, C.; Malta, S. Targeting of temozolomide using magnetic nanobeads: An in vitro study. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, Q.; Chow, P.K.; Wang, D.; Wang, C.H. Transferrin-conjugated magnetic silica PLGA nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin and paclitaxel for brain glioma treatment. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8511–8520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, M.; Yathindranath, V.; Thliveris, J.A.; Kopec, B.M.; Siahaan, T.J.; Miller, D.W. Doxorubicin-loaded iron oxide nanoparticles for glioblastoma therapy: A combinational approach for enhanced delivery of nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, J.S.; Lee, B.-S.; Zhang, M.; Yu, J.S. Nanotechnology for Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme. J. Transl. Int. Med. 2018, 6, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, X.; Gao, J.; Zhan, C.; Xie, C.; Chai, Z.; Ran, D.; Ying, M.; Zheng, P.; Lu, W. Liposome-based glioma targeted drug delivery enabled by stable peptide ligands. J. Control. Release 2015, 218, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Patel, T.R.; Sirianni, R.W.; Strohbehn, G.; Zheng, M.-Q.; Duong, N.; Schafbauer, T.; Huttner, A.J.; Huang, Y.; Carson, R.E.; et al. Highly penetrative, drug-loaded nanocarriers improve treatment of glioblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 11751–11756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, P.; Hu, L.; Yin, Q.; Feng, L.; Li, Y. Transferrin-modified c[RGDfK]-paclitaxel loaded hybrid micelle for sequential blood-brain barrier penetration and glioma targeting therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanti, T.; Stasik, A.; Burrow, A.J.; Alhnan, M.A.; Wan, K.W. Anti-glioma activity and the mechanism of cellular uptake of asiatic acid-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 500, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Correia-da-Silva, M.; Nunes, C.; Campos, J.; Sousa, E.; Silva, P.M.A.; Bousbaa, H.; Rodrigues, F.; Ferreira, D.; Costa, P.C.; et al. Discovery of a New Xanthone against Glioma: Synthesis and Development of (Pro)liposome Formulations. Molecules 2019, 24, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alves, A.; Costa, P.; Pinto, M.; Ferreira, D.; Correia-da-Silva, M. Small Molecules of Marine Origin as Potential Anti-Glioma Agents. Molecules 2021, 26, 2707. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092707

Alves A, Costa P, Pinto M, Ferreira D, Correia-da-Silva M. Small Molecules of Marine Origin as Potential Anti-Glioma Agents. Molecules. 2021; 26(9):2707. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092707

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlves, Ana, Paulo Costa, Madalena Pinto, Domingos Ferreira, and Marta Correia-da-Silva. 2021. "Small Molecules of Marine Origin as Potential Anti-Glioma Agents" Molecules 26, no. 9: 2707. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092707

APA StyleAlves, A., Costa, P., Pinto, M., Ferreira, D., & Correia-da-Silva, M. (2021). Small Molecules of Marine Origin as Potential Anti-Glioma Agents. Molecules, 26(9), 2707. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092707