Putative Anticancer Compounds from Plant-Derived Endophytic Fungi: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Anticancer Activity of Endophytic Fungi

2.1. Anti-Cancer Agents in Clinical Use Shared by Plants and Endophytic Fungi

2.2. Putative Anticancer Compounds from Endophytic Fungi

2.2.1. Alkaloids and Nitrogen-Containing Heterocycles

2.2.2. Benzo[j]fluoranthenes

2.2.3. Chromones

2.2.4. Coumarins

2.2.5. Depsidones

2.2.6. Depsipeptides

2.2.7. Ergochromes

2.2.8. Esters

2.2.9. Lactones

2.2.10. Lignans

2.2.11. Peptides

2.2.12. Polyketides

2.2.13. Quinones

2.2.14. Spirobisnaphthalenes

2.2.15. Terpenes (Diterpenes, Sesquiterpenes, Triterpenes)

2.2.16. Xanthones

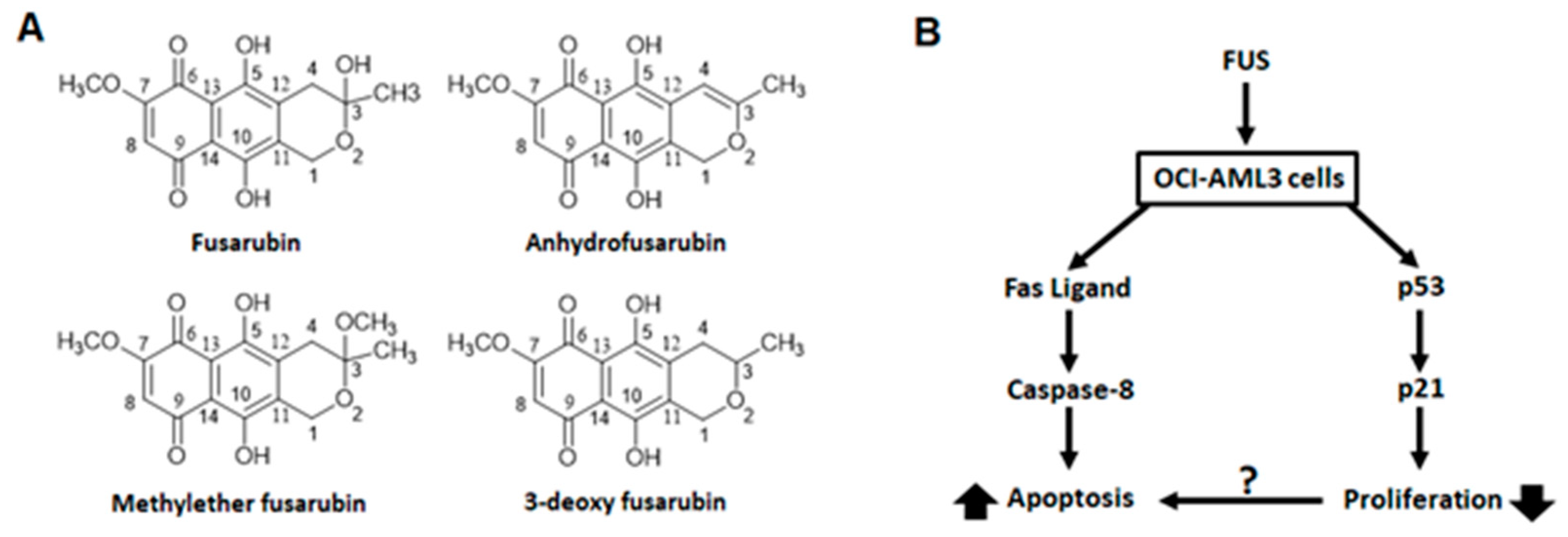

2.3. Recently Reported Metabolites with Potential Cytotoxicity and the Case of Fusarubin

3. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Fungus Name | Abbreviation |

| Allantophomopsis lycopodina | Allantophomopsis l. |

| Alternaria alternata | Alternaria a. |

| Alternaria tenuissima | Alternaria t. |

| Aspergillus clavatus | Aspergillus c. |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Aspergillus f. |

| Aspergillus glaucus | Aspergillus g. |

| Aspergillus niger | Aspergillus n. |

| Aspergillus parasiticus | Aspergillus p. |

| Aspergillus terreus | Aspergillus t. |

| Aspergillus violaceofuscus | Aspergillus v. |

| Bartalinia robillardoides | Bartalinia r. |

| Bionectria ochroleuca | Bionectria o. |

| Bipolaris setariae | Bipolaris s. |

| Botryosphaeria dothidea | Botryosphaeria d. |

| Botryosphaeria rhodina | Botryosphaeria r. |

| Ceriporia lacerate | Ceriporia l. |

| Chaetomium chiversii | Chaetomium c. |

| Chaetomium globosum | Chaetomium g. |

| Cladosporium cladosporioides | Cladosporium c. |

| Cladosporium oxysporum | Cladosporium o. |

| Colletotrichum capsici | Colletotrichum c. |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Colletotrichum g. |

| Cordyceps taii | Cordyceps t. |

| Diaporthe terebinthifolii | Diaporthe t. |

| Entrophospora infrequens | Entrophospora i. |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Fusarium o. |

| Fusarium solani | Fusarium s. |

| Guignardia bidwellii | Guignardia b. |

| Guignardia mangiferae | Guignardia m. |

| Hypocrea lixii | Hypocrea l. |

| Hypoxylon truncatum | Hypoxylon t. |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Lasiodiplodia t. |

| Mycelia sterilia | Mycelia s. |

| Microsphaeropsis arundinis | Microsphaeropsis a. |

| Myrothecium roridum | Myrothecium r. |

| Neurospora crassa | Neurospora c. |

| Papulaspora immersa | Papulaspora i. |

| Paraconiothyrium brasiliense | Paraconiothyrium b. |

| Penicillium chermesinum | Penicillium ch. |

| Penicillium citrinum | Penicillium ci. |

| Periconia atropurpurea | Periconia a. |

| Pestalotiopsis fici | Pestalotiopsis f. |

| Pestalotiopsis karstenii | Pestalotiopsis k. |

| Pestalotiopsis microspora | Pestalotiopsis m. |

| Pestalotiopsis pauciseta | Pestalotiopsis pa. |

| Pestalotiopsis photiniae | Pestalotiopsis ph. |

| Pestalotiopsis terminaliae | Pestalotiopsis t. |

| Pestalotiopsis versicolor | Pestalotiopsis v. |

| Pestalotiopsis neglecta | Pestalotiopsis n. |

| Phialocephala fortinii | Phialocephala f. |

| Phialophora mustea | Phialophora m. |

| Phoma betae | Phoma b. |

| Phomopsis longicolla | Phomopsis l. |

| Phyllosticta spinarum | Phyllosticta s. |

| Rhizopycnis vagum | Rhizopycnis v. |

| Rhytidhysteron rufulum | Rhytidhysteron r. |

| Setophoma terrestris | Setophoma t. |

| Stemphylium sedicola | Stemphylium s. |

| Stemphylium globuliferum | Stemphylium g. |

| Talaromyces flavus | Talaromyces f. |

| Talaromyces radicus | Talaromyces r. |

| Taxomyces andreanae | Taxomyces a. |

| Thielavia subthermophila | Thielavia s. |

| Trametes hirsuta | Trametes h. |

| Trichoderma gamsii | Trichoderma g. |

| Xylaria cf. cubensis | Xylaria cf. c. |

References

- Kumar, V.; Rai, S.; Gaur, P.; Fatima, T. Endophytic Fungi: Novel Sources of Anticancer Molecules. In Advances in Endophytic Research; Verma, V.C., Gange, A.C., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014; pp. 389–422. ISBN 978-81-322-1574-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gunatilaka, A.A.L. Natural Products from Plant-Associated Microorganisms: Distribution, Structural Diversity, Bioactivity, and Implications of Their Occurrence. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.W.; Song, Y.C.; Tan, R.X. Biology and Chemistry of Endophytes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 753–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.H.; Debbab, A.; Kjer, J.; Proksch, P. Fungal Endophytes from Higher Plants: A Prolific Source of Phytochemicals and Other Bioactive Natural Products. Fungal Divers. 2010, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniek, A.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; Kayser, O. Endophytes: Exploiting Biodiversity for the Improvement of Natural Product-Based Drug Discovery. J. Plant Interact. 2008, 3, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stierle, A.; Strobel, G.; Stierle, D. Taxol and Taxane Production by Taxomyces Andreanae, an Endophytic Fungus of Pacific Yew. Sci.-N. Y. THEN Wash. 1993, 260, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.H.; Sohrab, M.H.; Rony, S.R.; Tareq, F.S.; Hasan, C.M.; Mazid, M.A. Cytotoxic and Antibacterial Naphthoquinones from an Endophytic Fungus, Cladosporium sp. Toxicol. Rep. 2016, 3, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Afroz, F.; Begum, N.; Roy Rony, S.; Sharmin, S.; Moni, F.; Mahmood Hasan, C.; Shaha, K.; Sohrab, H. Endophytic Fusarium Solani: A Rich Source of Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Napthaquinone and Aza-Anthraquinone Derivatives. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorisio, S.; Fierabracci, A.; Muscari, I.; Liberati, A.M.; Cannarile, L.; Thuy, T.T.; Sung, T.V.; Sohrab, H.; Hasan, C.M.; Ayroldi, E.; et al. Fusarubin and Anhydrofusarubin Isolated from a Cladosporium Species Inhibit Cell Growth in Human Cancer Cell Lines. Toxins 2019, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shweta, S.; Zuehlke, S.; Ramesha, B.T.; Priti, V.; Mohana Kumar, P.; Ravikanth, G.; Spiteller, M.; Vasudeva, R.; Uma Shaanker, R. Endophytic Fungal Strains of Fusarium Solani, from Apodytes Dimidiata E. Mey. Ex Arn (Icacinaceae) Produce Camptothecin, 10-Hydroxycamptothecin and 9-Methoxycamptothecin. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S.C.; Verma, V.; Amna, T.; Qazi, G.N.; Spiteller, M. An Endophytic Fungus from Nothapodytes Foetida That Produces Camptothecin. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1717–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyberger, A.L.; Dondapati, R.; Porter, J.R. Endophyte Fungal Isolates from Podophyllum Peltatum Produce Podophyllotoxin. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusari, S.; Lamshöft, M.; Spiteller, M. Aspergillus Fumigatus Fresenius, an Endophytic Fungus from Juniperus Communis L. Horstmann as a Novel Source of the Anticancer pro-Drug Deoxypodophyllotoxin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, G.A.; Hess, W.M. Glucosylation of the Peptide Leucinostatin A, Produced by an Endophytic Fungus of European Yew, May Protect the Host from Leucinostatin Toxicity. Chem. Biol. 1997, 4, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yokoigawa, J.; Morimoto, K.; Shiono, Y.; Uesugi, S.; Kimura, K.; Kataoka, T. Allantopyrone A, an α-Pyrone Metabolite from an Endophytic Fungus, Inhibits the Tumor Necrosis Factor α-Induced Nuclear Factor ΚB Signaling Pathway. J. Antibiot. 2015, 68, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.H.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Indriani, I.D.; Wray, V.; Müller, W.E.; Totzke, F.; Zirrgiebel, U.; Schächtele, C.; Kubbutat, M.H.; Lin, W.H.; et al. Cytotoxic Metabolites from the Fungal Endophyte Alternaria sp. and Their Subsequent Detection in Its Host Plant Polygonum Senegalense. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassiano, I.T.; De Paulo, S.A.; Henriques Silva, N.; Cabral, M.C.; da Gloria da Costa Carvalho, M. Demonstration of the Lapachol as a Potential Drug for Reducing Cancer Metastasis. Oncol. Rep. 2005, 13, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Govindappa, M. First Report of Anticancer Agent, Lapachol Producing Endophyte, Aspergillus Niger of Tabebuia Argentea and Its in Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2014, 9, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- KIM, S.O.; KWON, J.I.; JEONG, Y.K.; KIM, G.Y.; KIM, N.D.; CHOI, Y.H. Induction of Egr-1 Is Associated with Anti-Metastatic and Anti-Invasive Ability of β-Lapachone in Human Hepatocarcinoma Cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 2169–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.H.; Cheong, J.; Park, Y.M.; Choi, Y.H. Down-Regulation of Cyclooxygenase-2 and Telomerase Activity by β-Lapachone in Human Prostate Carcinoma Cells. Pharmacol. Res. 2005, 51, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadananda, T.S.; Nirupama, R.; Chaithra, K.; Govindappa, M.; Chandrappa, C.P.; Vinay Raghavendra, B. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Endophytes from Tabebuia Argentea and Identification of Anticancer Agent (Lapachol). J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 3643–3652. [Google Scholar]

- Wuerzberger, S.M.; Pink, J.J.; Planchon, S.M.; Byers, K.L.; Bornmann, W.G.; Boothman, D.A. Induction of Apoptosis in MCF-7:WS8 Breast Cancer Cells by β-Lapachone. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 1876–1885. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Cox, D.G.; Ding, W.; Huang, G.; Lin, Y.; Li, C. Three New Resveratrol Derivatives from the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Alternaria sp. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 2840–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, C.-H.; Pan, J.-H.; Chen, B.; Yu, M.; Huang, H.-B.; Zhu, X.; Lu, Y.-J.; She, Z.-G.; Lin, Y.-C. Three Bianthraquinone Derivatives from the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Alternaria sp. ZJ9-6B from the South China Sea. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devari, S.; Jaglan, S.; Kumar, M.; Deshidi, R.; Guru, S.; Bhushan, S.; Kushwaha, M.; Gupta, A.P.; Gandhi, S.G.; Sharma, J.P.; et al. Capsaicin Production by Alternaria Alternata, an Endophytic Fungus from Capsicum Annum; LC–ESI–MS/MS Analysis. Phytochemistry 2014, 98, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shweta, S.; Gurumurthy, B.R.; Ravikanth, G.; Ramanan, U.S.; Shivanna, M.B. Endophytic Fungi from Miquelia Dentata Bedd., Produce the Anti-Cancer Alkaloid, Camptothecine. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2013, 20, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman, P.; Gnanasekar, S.; Chandrasekaran, R.; Chandrakasan, G.; Kadarkarai, M.; Sivaperumal, S. Isolation and Characterization of Anticancer Flavone Chrysin (5,7-Dihydroxy Flavone)-Producing Endophytic Fungi from Passiflora Incarnata L. Leaves. Ann. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, M.-H.; Wang, X.-B.; Li, T.-X.; Kong, L.-Y. Bioactive Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Alternaria Alternata. Fitoterapia 2014, 99, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.F.; Yu, S.S.; Zhou, W.Q.; Chen, X.G.; Ma, S.G.; Li, Y.; Qu, J. A New Isocoumarin from Metabolites of the Endophytic Fungus Alternaria Tenuissima (Nees & T. Nees: Fr.) Wiltshire. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2012, 23, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardane, A.M.D.A.; Kumar, N.S.; Jayasinghe, L.; Fujimoto, Y. Chemical Investigation of Metabolites Produced by an Endophytic Aspergillus sp. Isolated from Limonia Acidissima. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1384–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Fang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Su, W. Brefeldin A, a Cytotoxin Produced by Paecilomyces sp. and Aspergillus Clavatus Isolated from Taxus Mairei and Torreya Grandis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2002, 34, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ge, H.M.; Yu, Z.G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.H.; Tan, R.X. Bioactive Alkaloids from Endophytic Aspergillus Fumigatus. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C. An Alkaloid and a Steroid from the Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus Fumigatus. Molecules 2015, 20, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asker, M.; Mohamed, S.F.; Mahmoud, M.G.; Sayed, O.H.E. Antioxidant and Antitumor Activity of a New Sesquiterpene Isolated from Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus Glaucus. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2013, 5.2, 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Li, X.-M.; Meng, L.; Li, C.-S.; Gao, S.-S.; Shang, Z.; Proksch, P.; Huang, C.-G.; Wang, B.-G. Nigerapyrones A-H, α-Pyrone Derivatives from the Marine Mangrove-Derived Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus Niger MA-132. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 1787–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.C.; Li, H.; Ye, Y.H.; Shan, C.Y.; Yang, Y.M.; Tan, R.X. Endophytic Naphthopyrone Metabolites Are Co-Inhibitors of Xanthine Oxidase, SW1116 Cell and Some Microbial Growths. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 241, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stierle, A.A.; Stierle, D.B.; Bugni, T. Sequoiatones A and B: Novel Antitumor Metabolites Isolated from a Redwood Endophyte. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 5479–5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierle, D.B.; Stierle, A.A.; Bugni, T. Sequoiamonascins A–D: Novel Anticancer Metabolites Isolated from a Redwood Endophyte. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 4966–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, I.P.; Brissow, E.; Filho, L.C.K.; Senabio, J.; de Siqueira, K.A.; Filho, S.V.; Damasceno, J.L.; Mendes, S.A.; Tavares, D.C.; Magalhães, L.G.; et al. Bioactive Compounds of Aspergillus Terreus—F7, an Endophytic Fungus from Hyptis Suaveolens (L.) Poit. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutam, J.; Sharma, G.; Tiwari, V.K.; Mishra, A.; Kharwar, R.N.; Ramaraj, V.; Koch, B. Isolation and Characterization of “Terrein” an Antimicrobial and Antitumor Compound from Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus Terreus (JAS-2) Associated from Achyranthus Aspera Varanasi, India. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myobatake, Y.; Takemoto, K.; Kamisuki, S.; Inoue, N.; Takasaki, A.; Takeuchi, T.; Mizushina, Y.; Sugawara, F. Cytotoxic Alkylated Hydroquinone, Phenol, and Cyclohexenone Derivatives from Aspergillus Violaceofuscus Gasperini. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadevi, V.; Muthumary, J. Taxol, an Anticancer Drug Produced by an Endophytic Fungus Bartalinia Robillardoides Tassi, Isolated from a Medicinal Plant, Aegle Marmelos Correa Ex Roxb. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 24, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittayakhajonwut, P.; Dramae, A.; Madla, S.; Lartpornmatulee, N.; Boonyuen, N.; Tanticharoen, M. Depsidones from the Endophytic Fungus BCC 8616. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1361–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Tian, J.; Wang, X.; Mou, Y.; Mao, Z.; Lai, D.; Dai, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, M. Bioactive Spirobisnaphthalenes from the Endophytic Fungus Berkleasmium sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2151–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, W.; Kjer, J.; El Amrani, M.; Wray, V.; Lin, W.; Ebel, R.; Lai, D.; Proksch, P. Pullularins E and F, Two New Peptides from the Endophytic Fungus Bionectria Ochroleuca Isolated from the Mangrove Plant Sonneratia Caseolaris. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhatia, D.R.; Dhar, P.; Mutalik, V.; Deshmukh, S.K.; Verekar, S.A.; Desai, D.C.; Kshirsagar, R.; Thiagarajan, P.; Agarwal, V. Anticancer Activity of Ophiobolin A, Isolated from the Endophytic Fungus Bipolaris Setariae. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 1455–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, Y.-Q.; Tang, J.-J.; Zhang, A.-L.; Gao, J.-M. Secondary Metabolites from the Endophytic Botryosphaeria Dothidea of Melia Azedarach and Their Antifungal, Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Cytotoxic Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3584–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, R.; Scherlach, K.; Dahse, H.-M.; Sattler, I.; Hertweck, C. Botryorhodines A–D, Antifungal and Cytotoxic Depsidones from Botryosphaeria Rhodina, an Endophyte of the Medicinal Plant Bidens Pilosa. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Ren, F.; Niu, S.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Che, Y. Guanacastane Diterpenoids from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Cercospora sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.-M.; Shan, W.-G.; Zhang, L.-W.; Zhan, Z.-J. Ceriponols A-K, Tremulane Sesquitepenes from Ceriporia Lacerate HS-ZJUT-C13A, a Fungal Endophyte of Huperzia Serrata. Phytochemistry 2013, 95, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbab, A.; Aly, H.A.; Edrada-Ebel, R.A.; Müller, W.E.; Mosaddak, M.; Hakiki, A.; Ebel, R.; Proksch, P. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Chaetomium sp. Isolated from Salvia Officinalis Growing in Morocco. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2009, 13, 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Jiang, J.; Hu, S.; Ma, H.; Zhu, H.; Tong, Q.; Cheng, L.; Hao, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y. Secondary Metabolites from Endophytic Fungus Chaetomium sp. Induce Colon Cancer Cell Apoptotic Death. Fitoterapia 2017, 121, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Tong, Q.; Ma, H.; Xu, H.; Hu, S.; Ma, W.; Xue, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Song, H.; et al. Indole Diketopiperazines from Endophytic Chaetomium Sp 88194 Induce Breast Cancer Cell Apoptotic Death. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, R.H.; Xu, S.; Liu, J.Y.; Ge, H.M.; Ding, H.; Xu, C.; Zhu, H.L.; Tan, R.X. Chaetominine, a Cytotoxic Alkaloid Produced by Endophytic Chaetomium sp. IFB-E015. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5709–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turbyville, T.J.; Wijeratne, E.K.; Liu, M.X.; Burns, A.M.; Seliga, C.J.; Luevano, L.A.; David, C.L.; Faeth, S.H.; Whitesell, L.; Gunatilaka, A.L. Search for Hsp90 Inhibitors with Potential Anticancer Activity: Isolation and SAR Studies of Radicicol and Monocillin I from Two Plant-Associated Fungi of the Sonoran Desert. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Ren, W.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, X. Bioactive Metabolites from Chaetomium Globosum L18, an Endophytic Fungus in the Medicinal Plant Curcuma Wenyujin. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2012, 19, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Song, Y.C.; Chen, J.R.; Xu, C.; Ge, H.M.; Wang, X.T.; Tan, R.X. Chaetoglobosin U, a Cytochalasan Alkaloid from Endophytic Chaetomium Globosum IFB-E019. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashyal, B.P.; Wijeratne, E.K.; Faeth, S.H.; Gunatilaka, A.L. Globosumones A- C, Cytotoxic Orsellinic Acid Esters from the Sonoran Desert Endophytic Fungus Chaetomium Globosum 1. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiao, J.; Gao, Y.-Q.; Tang, J.; Zhang, A.-L.; Gao, J.-M. Chaetoglobosins from Chaetomium Globosum, an Endophytic Fungus in Ginkgo Biloba, and Their Phytotoxic and Cytotoxic Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3734–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadevi, V.; Muthumary, J. Taxol Production by Pestalotiopsis Terminaliae, an Endophytic Fungus of Terminalia Arjuna (Arjun Tree). Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2009, 52, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhou, P.-P.; Yu, L.-J. An Endophytic Taxol-Producing Fungus from Taxus Media, Cladosporium Cladosporioides MD2. Curr. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokul Raj, K.; Manikandan, R.; Arulvasu, C.; Pandi, M. Anti-Proliferative Effect of Fungal Taxol Extracted from Cladosporium Oxysporum against Human Pathogenic Bacteria and Human Colon Cancer Cell Line HCT 15. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 138, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, K.G.; Sambantham, S.; Manikanadan, R.; Arulvasu, C.; Pandi, M. Fungal Taxol Extracted from Cladosporium Oxysporum Induces Apoptosis in T47D Human Breast Cancer Cell Line. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 6627–6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumaran, R.S.; Jung, H.; Kim, H.J. In Vitro Screening of Taxol, an Anticancer Drug Produced by the Fungus, Colletotrichum Capsici. Eng. Life Sci. 2011, 11, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, K. A New Endophytic Taxol-and Baccatin III-Producing Fungus Isolated from Taxus Chinensis Var. Mairei. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 16379–16386. [Google Scholar]

- Bungihan, M.; Tan, A.M.; Takayama, H.; Cruz, D.E.; Nonato, G.M. A New Macrolide Isolated from the Endophytic Fungus Colletotrichum sp. Philipp. Sci. Lett. 2013, 6, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.-G.; Pan, W.-D.; Lou, H.-Y.; Liu, R.-M.; Xiao, J.-H.; Zhong, J.-J. New Cytochalasins from Medicinal Macrofungus Crodyceps Taii and Their Inhibitory Activities against Human Cancer Cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 1823–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Sun, P.; Li, T.; Kurtán, T.; Mándi, A.; Antus, S.; Krohn, K.; Draeger, S.; Schulz, B.; Yi, Y.; et al. Bioactive Nonanolide Derivatives Isolated from the Endophytic Fungus Cytospora sp. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 9699–9710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedukondalu, N.; Arora, P.; Wadhwa, B.; Malik, F.A.; Vishwakarma, R.A.; Gupta, V.K.; Riyaz-Ul-Hassan, S.; Ali, A. Diapolic Acid A–B from an Endophytic Fungus, Diaporthe Terebinthifolii Depicting Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaka, M.; Palasarn, S.; Lapanun, S.; Chanthaket, R.; Boonyuen, N.; Lumyong, S. γ-Lactones and Ent-Eudesmane Sesquiterpenes from the Endophytic Fungus Eutypella sp. BCC 13199. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1720–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-X.; Li, S.-F.; Zhao, F.; Dai, H.-Q.; Bao, L.; Ding, R.; Gao, H.; Zhang, L.-X.; Wen, H.-A.; Liu, H.-W. Chemical Constituents from Endophytic Fungus Fusarium Oxysporum. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elavarasi, A.; Rathna, G.S.; Kalaiselvam, M. Taxol Producing Mangrove Endophytic Fungi Fusarium Oxysporum from Rhizophora Annamalayana. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, S1081–S1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, R.S.; Kim, H.J.; Hur, B.-K. Taxol Promising Fungal Endophyte, Pestalotiopsis Species Isolated from Taxus Cuspidata. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2010, 110, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palem, P.P.C.; Kuriakose, G.C.; Jayabaskaran, C. An Endophytic Fungus, Talaromyces Radicus, Isolated from Catharanthus Roseus, Produces Vincristine and Vinblastine, Which Induce Apoptotic Cell Death. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, B.; Li, H.; Zeng, S.; Shao, H.; Gu, S.; Wei, R. Preliminary Study on the Isolation of Endophytic Fungus of Catharanthus Roseus and Its Fermentation to Produce Products of Therapeutic Value. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2000, 31, 805–807. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, L.; Skjerve, E.; Eriksen, G.S.; Uhlig, S. Cytotoxicity of Enniatins A, A1, B, B1, B2 and B3 from Fusarium Avenaceum. Toxicon Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinology 2006, 47, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Burns, A.M.; Liu, M.X.; Faeth, S.H.; Gunatilaka, A.A.L. Search for Cell Motility and Angiogenesis Inhibitors with Potential Anticancer Activity: Beauvericin and Other Constituents of Two Endophytic Strains of Fusarium Oxysporum. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuska, J.; Proksa, B.; Fusková, A. New Potential Cytotoxic and Antitumor Substances I. In Vitro Effect of Bikaverin and Its Derivatives on Cells of Certain Tumors. Neoplasma 1975, 22, 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem, M.; Ram, M.; Alam, P.; Ahmad, M.M.; Mohammad, A.; Al-Qurainy, F.; Khan, S.; Abdin, M.Z. Fusarium Solani, P1, a New Endophytic Podophyllotoxin-Producing Fungus from Roots of Podophyllum Hexandrum. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 6, 2493–2499. [Google Scholar]

- Kusari, S.; Zühlke, S.; Spiteller, M. An Endophytic Fungus from Camptotheca Acuminata That Produces Camptothecin and Analogues. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gou, H.; Du, Z.; Liu, X.-Z.; Che, Y.; Ye, X. Ecology-Based Screen Identifies New Metabolites from a Cordyceps-Colonizing Fungus as Cancer Cell Proliferation Inhibitors and Apoptosis Inducers. Cell Prolif. 2009, 42, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommart, U.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Trisuwan, K.; Tadpetch, K.; Phongpaichit, S.; Preedanon, S.; Sakayaroj, J. Tricycloalternarene Derivatives from the Endophytic Fungus Guignardia Bidwellii PSU-G11. Phytochem. Lett. 2012, 5, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.-H.; Liang, F.-L.; Wu, W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Pan, Q.-L.; Li, H.-H.; Ye, W.; Liu, H.-X.; Li, S.-N.; Tan, G.-H.; et al. Guignardones P–S, New Meroterpenoids from the Endophytic Fungus Guignardia Mangiferae A348 Derived from the Medicinal Plant Smilax Glabra. Molecules 2015, 20, 22900–22907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, J.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C.; Luo, M.; Mu, F.; Fu, Y.; Zu, Y.; Yao, M. Hypocrea Lixii, Novel Endophytic Fungi Producing Anticancer Agent Cajanol, Isolated from Pigeon Pea (Cajanus Cajan [L.] Millsp.). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 115, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Ge, H.M.; Song, Y.C.; Ding, H.; Zhu, H.L.; Zhao, X.A.; Tan, R.X. Cytotoxic Benzo [j] Fluoranthene Metabolites from Hypoxylon Truncatum IFB-18, an Endophyte of Artemisia Annua. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinworrungsee, M.; Wiyakrutta, S.; Sriubolmas, N.; Chuailua, P.; Suksamrarn, A. Cytotoxic Activities of Trichothecenes Isolated from an Endophytic Fungus Belonging to Order Hypocreales. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2008, 31, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandi, M.; Kumaran, R.S.; Choi, Y.-K.; Kim, H.J.; Muthumary, J. Isolation and Detection of Taxol, an Anticancer Drug Produced from Lasiodiplodia Theobromae, an Endophytic Fungus of the Medicinal Plant Morinda Citrifolia. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Sobreira, A.C.M.; Pessoa, O.D.L.; Florêncio, K.G.D.; Wilke, D.V.; Freire, F.C.O.; Gonçalves, F.J.T.; Ribeiro, P.R.V.; Silva, L.M.A.; Brito, E.S.; Canuto, K.M. Resorcylic Lactones from Lasiodiplodia Theobromae (MUB65), a Fungal Endophyte Isolated from Myracrodruon Urundeuva. Planta Med. 2016, 82, P671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Guo, B.; Guo, S. Preliminary Study of a Vincristine-Proudcing Endophytic Fungus Isolated from Leaves of Catharanthus Roseus. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2004, 35, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Sar, S.A.; Blunt, J.W.; Munro, M.H.G. Spiro-Mamakone A: A Unique Relative of the Spirobisnaphthalene Class of Compounds. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 2059–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, E.; Varughese, T.; Spadafora, C.; Arnold, A.E.; Coley, P.D.; Kursar, T.A.; Gerwick, W.H.; Cubilla-Rios, L. Chemical Constituents of the New Endophytic Fungus Mycosphaerella sp. Nov. and Their Anti-Parasitic Activity. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, J.; Liu, X.; Li, E.; Guo, L.; Che, Y. Arundinols A–C and Arundinones A and B from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Microsphaeropsis Arundinis. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, H.E.; Graupner, P.R.; Asai, Y.; TenDyke, K.; Qiu, D.; Shen, Y.Y.; Rios, N.; Arnold, A.E.; Coley, P.D.; Kursar, T.A.; et al. Mycoleptodiscins A and B, Cytotoxic Alkaloids from the Endophytic Fungus Mycoleptodiscus sp. F0194. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Wang, G.; Shan, W.; Zeng, D.; Ding, R.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, D.; Liu, X.; Yang, S.; Chen, H. Myrotheciumones: Bicyclic Cytotoxic Lactones Isolated from an Endophytic Fungus of Ajuga Decumbens. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 2504–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhu, L.; Tan, Q.; Wan, D.; Xie, J.; Peng, J. New Cytotoxic Trichothecene Macrolide Epimers from Endophytic Myrothecium Roridum IFB-E012. J. Antibiot. 2016, 69, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Shawl, A.S.; Kour, A.; Andrabi, R.; Sudan, P.; Sultan, P.; Verma, V.; Qazi, G.N. An Endophytic Neurospora sp. from Nothapodytes Foetida Producing Camptothecin. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2008, 44, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-C.; Li, D.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Zhang, W.-M. A New Isofuranonaphthalenone and Benzopyrans from the Endophytic Fungus Nodulisporium sp. A4 from Aquilaria Sinensis. Helv. Chim. Acta 2010, 93, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges Coutinho Gallo, M.; Coêlho Cavalcanti, B.; Washington Araújo Barros, F.; Odorico de Moraes, M.; Veras Costa-Lotufo, L.; Pessoa, C.; Kenupp Bastos, J.; Tallarico Pupo, M. Chemical Constituents of Papulaspora Immersa, an Endophyte from Smallanthus Sonchifolius (Asteraceae), and Their Cytotoxic Activity. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 2941–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiono, Y.; Kikuchi, M.; Koseki, T.; Murayama, T.; Kwon, E.; Aburai, N.; Kimura, K. Isopimarane Diterpene Glycosides, Isolated from Endophytic Fungus Paraconiothyrium sp. MY-42. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Guo, L.; Cao, Y.; Che, Y. Bisabolane Sesquiterpenoids from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Paraconiothyrium Brasiliense. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yang, J.; Cai, X.; She, Z.; Lin, Y. A New Furanocoumarin from the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Penicillium sp. (ZH16). Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 1291–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.-J.; Lu, Z.-Y.; Zhu, T.-J.; Fang, Y.-C.; Gu, Q.-Q.; Zhu, W.-M. Penicillenols from Penicillium sp. GQ-7, an Endophytic Fungus Associated with Aegiceras Corniculatum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, Z.; Zhu, T.; Fang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Zhu, W. Polyketides from Penicillium sp. JP-1, an Endophytic Fungus Associated with the Mangrove Plant Aegiceras Corniculatum. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-J.; Fu, Y.-W.; Zhou, Q.-Y. Penifupyrone, a New Cytotoxic Funicone Derivative from the Endophytic Fungus Penicillium sp. HSZ-43. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1544–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Kong, X.; Gao, H.; Zhu, T.; Wu, G.; Gu, Q.; Li, D. Two New Meroterpenoids Produced by the Endophytic Fungus Penicillium sp. SXH-65. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darsih, C.; Prachyawarakorn, V.; Wiyakrutta, S.; Mahidol, C.; Ruchirawat, S.; Kittakoop, P. Cytotoxic Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Penicillium Chermesinum: Discovery of a Cysteine-Targeted Michael Acceptor as a Pharmacophore for Fragment-Based Drug Discovery, Bioconjugation and Click Reactions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 70595–70603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Neketi, M.; Ebrahim, W.; Lin, W.; Gedara, S.; Badria, F.; Saad, H.-E.A.; Lai, D.; Proksch, P. Alkaloids and Polyketides from Penicillium Citrinum, an Endophyte Isolated from the Moroccan Plant Ceratonia Siliqua. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.-L.; Zhang, D.-W.; Li, L.; Xie, D.; Zou, J.-H.; Si, Y.-K.; Dai, J. Two New Terpenoids from Endophytic Fungus Periconia sp. F-31. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 59, 1541–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teles, H.L.; Sordi, R.; Silva, G.H.; Castro-Gamboa, I.; da Silva Bolzani, V.; Pfenning, L.H.; de Abreu, L.M.; Costa-Neto, C.M.; Young, M.C.M.; Araújo, Â.R. Aromatic Compounds Produced by Periconia Atropurpurea, an Endophytic Fungus Associated with Xylopia Aromatica. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 2686–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Kjer, J.; Sendker, J.; Wray, V.; Guan, H.; Edrada, R.; Lin, W.; Wu, J.; Proksch, P. Chromones from the Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis sp. Isolated from the Chinese Mangrove Plant Rhizophora Mucronata. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 662–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A.; Carroll, A.R.; Andrews, K.T.; Boyle, G.M.; Tran, T.L.; Healy, P.C.; Kalaitzis, J.A.; Shivas, R.G. Pestalactams A–C: Novel Caprolactams from the Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis sp. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, L.-S.; Jia, M.; Chen, L.; Zhu, B.; Dong, H.-X.; Si, J.-P.; Peng, W.; Han, T. Cytotoxic and Antifungal Constituents Isolated from the Metabolites of Endophytic Fungus DO14 from Dendrobium Officinale. Molecules 2015, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Guo, L.; Che, Y.; Liu, L. Pestaloficiols Q–S from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis Fici. Fitoterapia 2013, 85, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU, S.-C.; YE, X.; GUO, L.-D.; LIU, L. Cytotoxic Isoprenylated Epoxycyclohexanediols from the Plant Endophyte Pestalotiopsis Fici. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2011, 9, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Niu, S.; Guo, L.; Chen, X.; Che, Y. Isoprenylated Chromone Derivatives from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis Fici. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1482–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.Q.; Zhang, L.; Shi, B.Z.; Song, X.M. Two New Oxysporone Derivatives from the Fermentation Broth of the Endophytic Plant Fungus Pestalotiopsis Karstenii Isolated from Stems of Camellia Sasanqua. Molecules 2012, 17, 8554–8560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumaran, R.S.; Choi, Y.-K.; Lee, S.; Jeon, H.J.; Jung, H.; Kim, H.J. Isolation of Taxol, an Anticancer Drug Produced by the Endophytic Fungus, Phoma Betae. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 950–960. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, L.; Rajagopal, K.; Subbarayan, K.; Ulagappan, K.; Sampath, A.; Karthik, G. Efficiency of Fungal Taxol on Human Liver Carcinoma Cell Lines. Am. J. Res. Commun. 2013, 1, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.C.; Strobel, G.A.; Lobkovsky, E.; Clardy, J. Torreyanic Acid: A Selectively Cytotoxic Quinone Dimer from the Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis Microspora. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 3232–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, A.M.; Haddad, A.; Worapong, J.; Long, D.M.; Ford, E.J.; Hess, W.M.; Strobel, G.A. Induction of the Sexual Stage of Pestalotiopsis Microspora, a Taxol-Producing Fungus. Microbiology 2000, 146, 2079–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vennila, R.; Kamalraj, S.; Muthumary, J. In Vitro Studies on Anticancer Activity of Fungal Taxol against Human Breast Cancer Cell Line MCF-7 Cells. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, S1159–S1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Qi, Y.; Liu, S.; Guo, L.; Chen, X. Photipyrones A and B, New Pyrone Derivatives from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis Photiniae. J. Antibiot. 2012, 65, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, G.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Guo, L.; Che, Y. Photinides A–F, Cytotoxic Benzofuranone-Derived γ-Lactones from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis Photiniae. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 942–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalli, Y.; Mirza, D.N.; Wani, Z.A.; Wadhwa, B.; Mallik, F.A.; Raina, C.; Chaubey, A.; Riyaz-Ul-Hassan, S.; Ali, A. Phialomustin A–D, New Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Metabolites from an Endophytic Fungus, Phialophora Mustea. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 95307–95312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, C.; Sun, L.; Munro, M.H.G.; Santhanam, J. Polyketide and Benzopyran Compounds of an Endophytic Fungus Isolated from C Innamomum Mollissimum: Biological Activity and Structure. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Yang, R.; Yin, X.; Li, X.; Luo, W.; She, Z.; Lin, Y. Chemistry and Cytotoxic Activities of Polyketides Produced by the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Phomopsis SP. ZSU-H76. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2009, 45, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yang, J.; Lei, F.; She, Z.; Lin, Y. A New Xanthone O-Glycoside from the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Phomopsis sp. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2013, 49, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, L.; Yang, L.; Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Shen, Y. Phomopsidone A, a Novel Depsidone Metabolite from the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Phomopsis sp. A123. Fitoterapia 2014, 96, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaka, M.; Jaturapat, A.; Rukseree, K.; Danwisetkanjana, K.; Tanticharoen, M.; Thebtaranonth, Y. Phomoxanthones A and B, Novel Xanthone Dimers from the Endophytic Fungus Phomopsis Species. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1015–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyapaiboonsri, T.; Yoiprommarat, S.; Srikitikulchai, P.; Srichomthong, K.; Lumyong, S. Oblongolides from the Endophytic Fungus Phomopsis sp. BCC 9789. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouda, J.-B.; Tamokou, J.-D.; Mbazoa, C.D.; Douala-Meli, C.; Sarkar, P.; Bag, P.K.; Wandji, J. Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Cytochalasins from the Endophytic Fungus Phomopsis sp. Harbored in Garcinia Kola (Heckel) Nut. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wagenaar, M.M.; Clardy, J. Dicerandrols, New Antibiotic and Cytotoxic Dimers Produced by the Fungus Phomopsis Longicolla Isolated from an Endangered Mint. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1006–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijeratne, E.K.; Paranagama, P.A.; Marron, M.T.; Gunatilaka, M.K.; Arnold, A.E.; Gunatilaka, A.L. Sesquiterpene Quinones and Related Metabolites from Phyllosticta Spinarum, a Fungal Strain Endophytic in Platycladus Orientalis of the Sonoran Desert (1). J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.K.; Mishra, P.D.; Kulkarni-Almeida, A.; Verekar, S.; Sahoo, M.R.; Periyasamy, G.; Goswami, H.; Khanna, A.; Balakrishnan, A.; Vishwakarma, R. Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Activity of Ergoflavin Isolated from an Endophytic Fungus. Chem. Biodivers. 2009, 6, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shi, Q.; Lin, G.; Guo, S.; Yang, J. Spirobisnaphthalene Analogues from the Endophytic Fungus Preussia sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1712–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, M.M.; Corwin, J.; Strobel, G.; Clardy, J. Three New Cytochalasins Produced by an Endophytic Fungus in the Genus Rhinocladiella. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1692–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudhom, K.; Teerawatananond, T.; Chookpaiboon, S. Spirobisnaphthalenes from the Mangrove-Derived Fungus Rhytidhysteron sp. AS21B. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, D.; Wang, A.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, K.; Mao, Z.; Dong, X.; Tian, J.; Xu, D.; Dai, J.; Peng, Y.; et al. Bioactive Dibenzo-α-Pyrone Derivatives from the Endophytic Fungus Rhizopycnis Vagum Nitaf22. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2022–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siridechakorn, I.; Yue, Z.; Mittraphab, Y.; Lei, X.; Pudhom, K. Identification of Spirobisnaphthalene Derivatives with Anti-Tumor Activities from the Endophytic Fungus Rhytidhysteron Rufulum AS21B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 2878–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Elimat, T.; Figueroa, M.; Raja, H.A.; Graf, T.N.; Swanson, S.M.; Falkinham, J.O.; Wani, M.C.; Pearce, C.J.; Oberlies, N.H. Biosynthetically Distinct Cytotoxic Polyketides from Setophoma Terrestris. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2015, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.-N.; Bashyal, B.P.; Wijeratne, E.M.K.; U’Ren, J.M.; Liu, M.X.; Gunatilaka, M.K.; Arnold, A.E.; Gunatilaka, A.A.L. Smardaesidins A–G, Isopimarane and 20-Nor-Isopimarane Diterpenoids from Smardaea sp., a Fungal Endophyte of the Moss Ceratodon Purpureus. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 2052–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mirjalili, M.H.; Farzaneh, M.; Bonfill, M.; Rezadoost, H.; Ghassempour, A. Isolation and Characterization of Stemphylium Sedicola SBU-16 as a New Endophytic Taxol-Producing Fungus from Taxus Baccata Grown in Iran. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012, 328, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Debbab, A.; Aly, A.H.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Wray, V.; Müller, W.E.G.; Totzke, F.; Zirrgiebel, U.; Schächtele, C.; Kubbutat, M.H.G.; Lin, W.H.; et al. Bioactive Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Stemphylium Globuliferum Isolated from Mentha Pulegium. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teiten, M.-H.; Mack, F.; Debbab, A.; Aly, A.H.; Dicato, M.; Proksch, P.; Diederich, M. Anticancer Effect of Altersolanol A, a Metabolite Produced by the Endophytic Fungus Stemphylium Globuliferum, Mediated by Its pro-Apoptotic and Anti-Invasive Potential via the Inhibition of NF-ΚB Activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 3850–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.-H.; Yang, Z.-D.; Shu, Z.-M.; Wang, Y.-G.; Wang, M.-G. Secondary Metabolites and Biological Activities of Talaromyces sp. LGT-2, an Endophytic Fungus from Tripterygium Wilfordii. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. IJPR 2016, 15, 453–457. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Huang, H.; Shao, C.; Huang, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Lu, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Cytotoxic Norsesquiterpene Peroxides from the Endophytic Fungus Talaromyces Flavus Isolated from the Mangrove Plant Sonneratia Apetala. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusari, S.; Zühlke, S.; Košuth, J.; Čellárová, E.; Spiteller, M. Light-Independent Metabolomics of Endophytic Thielavia Subthermophila Provides Insight into Microbial Hypericin Biosynthesis. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S.C.; Nazir, A.; Chawla, R.; Arora, R.; Riyaz-ul-Hasan, S.; Amna, T.; Ahmed, B.; Verma, V.; Singh, S.; Sagar, R.; et al. The Endophytic Fungus Trametes Hirsuta as a Novel Alternative Source of Podophyllotoxin and Related Aryl Tetralin Lignans. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 122, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Chen, A.J.; Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Zou, Z. Trichoderones A and B: Two Pentacyclic Cytochalasans from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Trichoderma Gamsii. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2012, 2516–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taware, R.; Abnave, P.; Patil, D.; Rajamohananan, P.R.; Raja, R.; Soundararajan, G.; Kundu, G.C.; Ahmad, A. Isolation, Purification and Characterization of Trichothecinol-A Produced by Endophytic Fungus Trichothecium sp. and Its Antifungal, Anticancer and Antimetastatic Activities. Sustain. Chem. Process. 2014, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chokpaiboon, S.; Sommit, D.; Teerawatananond, T.; Muangsin, N.; Bunyapaiboonsri, T.; Pudhom, K. Cytotoxic Nor-Chamigrane and Chamigrane Endoperoxides from a Basidiomycetous Fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaka, M.; Chinthanom, P.; Boonruangprapa, T.; Rungjindamai, N.; Pinruan, U. Eremophilane-Type Sesquiterpenes from the Fungus Xylaria sp. BCC 21097. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansuwan, S.; Pornpakakul, S.; Roengsumran, S.; Petsom, A.; Muangsin, N.; Sihanonta, P.; Chaichit, N. Antimalarial Benzoquinones from an Endophytic Fungus, Xylaria sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 1620–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Xu, Y.; Espinosa-Artiles, P.; Liu, M.X.; Luo, J.-G.; U’Ren, J.M.; Elizabeth Arnold, A.; Leslie Gunatilaka, A.A. Sesquiterpenes and Other Constituents of Xylaria sp. NC1214, a Fungal Endophyte of the Moss Hypnum sp. Phytochemistry 2015, 118, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, J.; Sun, Q.-Q.; Qin, J.-C.; Pescitelli, G.; Gao, J.-M. Characterization of Cytochalasins from the Endophytic Xylaria sp. and Their Biological Functions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 10962–10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawadsitang, S.; Mongkolthanaruk, W.; Suwannasai, N.; Sodngam, S. Antimalarial and Cytotoxic Constituents of Xylaria Cf. Cubensis PK108. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 2033–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Lin, X.; Lu, C.-H.; Shen, Y.-M. Three New Triterpenes from Xylarialean sp. A45, an Endophytic Fungus from Annona Squamosa L. Helv. Chim. Acta 2011, 94, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tao, L.; Liang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Dai, C.; Xia, X.; She, Z.; Lin, Y.; Fu, L. Secalonic Acid D Induced Leukemia Cell Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest of G(1) with Involvement of GSK-3beta/Beta-Catenin/c-Myc Pathway. Cell Cycle Georget. Tex 2009, 8, 2444–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamdem, R.S.T.; Wang, H.; Wafo, P.; Ebrahim, W.; Özkaya, F.C.; Makhloufi, G.; Janiak, C.; Sureechatchaiyan, P.; Kassack, M.U.; Lin, W.; et al. Induction of New Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Bionectria sp. through Bacterial Co-Culture. Fitoterapia 2018, 124, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Al Haidari, R.A.; Zayed, M.F.; El-Kholy, A.A.; Elkhayat, E.S.; Ross, S.A. Fusarithioamide B, a New Benzamide Derivative from the Endophytic Fungus Fusarium Chlamydosporium with Potent Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Tang, P.; Liu, Z.; Guo, G.-J.; Sun, Q.-Y.; Yin, J. Identification of a New Uncompetitive Inhibitor of Adenosine Deaminase from Endophyte Aspergillus Niger sp. Curr. Microbiol. 2018, 75, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.-M.; Li, L.-Y.; Sun, L.-Y.; Sun, B.-D.; Niu, S.-B.; Wang, M.-H.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Sun, W.-S.; Zhang, G.-S.; Deng, H.; et al. Spiciferone Analogs from an Endophytic Fungus Phoma Betae Collected from Desert Plants in West China. J. Antibiot. 2018, 71, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.-Y.; Li, Y.; Lyu, X.-X.; Liu, Y.-B. Investigations on secondary metabolites of endophyte Diaporthe sp. hosted in Tylophora ovata. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2018, 43, 2944–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Singamaneni, V.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, A.; Arora, D.; Kushwaha, M.; Bhushan, S.; Jaglan, S.; Gupta, P. Valproic Acid Induces Three Novel Cytotoxic Secondary Metabolites in Diaporthe sp., an Endophytic Fungus from Datura Inoxia Mill. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 2217–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Kushwaha, M.; Arora, D.; Jain, S.; Singamaneni, V.; Sharma, S.; Shankar, R.; Bhushan, S.; Gupta, P.; Jaglan, S. New Cytochalasin from Rosellinia Sanctae-Cruciana, an Endophytic Fungus of Albizia Lebbeck. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdem, R.S.T.; Pascal, W.; Rehberg, N.; van Geelen, L.; Höfert, S.-P.; Knedel, T.-O.; Janiak, C.; Sureechatchaiyan, P.; Kassack, M.U.; Lin, W.; et al. Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Cylindrocarpon sp. Isolated from Tropical Plant Sapium Ellipticum. Fitoterapia 2018, 128, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.-N.T.; Nguyen, D.T.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Chu, H.H.; Chu, S.K.; Chau, M.V.; Phi, Q.-T. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Properties of Bioactive Metabolites Produced by Streptomyces Cavourensis YBQ59 Isolated from Cinnamomum Cassia Prels in Yen Bai Province of Vietnam. Curr. Microbiol. 2018, 75, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-X.; Tan, H.-B.; Chen, Y.-C.; Li, S.-N.; Li, H.-H.; Zhang, W.-M. Secondary Metabolites from the Colletotrichum Gloeosporioides A12, an Endophytic Fungus Derived from Aquilaria Sinensis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 2360–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Mao, Z.; Guo, H.; Xie, Y.; Cui, Z.; Sun, J.; Wu, H.; Wen, X.; Wang, J.; Shan, T. Mollicellins O–R, Four New Depsidones Isolated from the Endophytic Fungus Chaetomium sp. Eef-10. Molecules 2018, 23, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, J.; Li, G.; Deng, Q.; Zheng, D.; Yang, X.; Xu, J. Cytotoxic Constituents from the Mangrove Endophytic Pestalotiopsis sp. Induce G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Human Cancer Cells. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 2968–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariantari, N.P.; Ancheeva, E.; Wang, C.; Mándi, A.; Knedel, T.-O.; Kurtán, T.; Chaidir, C.; Müller, W.E.G.; Kassack, M.U.; Janiak, C.; et al. Indole Diterpenoids from an Endophytic Penicillium sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil Kumar, V.; Kumaresan, S.; Tamizh, M.M.; Hairul Islam, M.I.; Thirugnanasambantham, K. Anticancer Potential of NF-ΚB Targeting Apoptotic Molecule “Flavipin” Isolated from Endophytic Chaetomium Globosum. Phytomedicine 2019, 61, 152830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-X.; Zheng, M.-J.; Li, J.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.-H.; Huang, R.; Zheng, Y.-S.; Sun, H.; Ai, H.-L.; Liu, J.-K. Cytotoxic Polyketides from Endophytic Fungus Phoma Bellidis Harbored in Ttricyrtis Maculate. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 29, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwoko, H.; Daletos, G.; Stuhldreier, F.; Lee, J.; Wesselborg, S.; Feldbrügge, M.; Müller, W.E.G.; Kalscheuer, R.; Ancheeva, E.; Proksch, P. Dithiodiketopiperazine Derivatives from Endophytic Fungi Trichoderma Harzianum and Epicoccum Nigrum. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.-Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, M.-H.; Kong, L.-Y. Cytotoxic Seco-Cytochalasins from an Endophytic Aspergillus sp. Harbored in Pinellia Ternata Tubers. Fitoterapia 2019, 132, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, C.; Chang, S.; Shao, R.; Xing, J.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Si, S. Cytotoxic Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Chaetomium Globosum 7951. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 16035–16039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, F.; Hou, S.-Y.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Yan, X.-M.; Xia, M.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-X. Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Indole Alkaloids from an Endophytic Fungus Chaetomium sp. SYP-F7950 of Panax Notoginseng. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 28754–28763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; He, J.; Wang, L.; Yuan, J.; She, Z. Ascomylactams A–C, Cytotoxic 12- or 13-Membered-Ring Macrocyclic Alkaloids Isolated from the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Didymella sp. CYSK-4, and Structure Revisions of Phomapyrrolidones A and C. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xu, K.; Chen, W.-Q.; Guo, Z.-H.; Liu, Y.-T.; Qiao, Y.-N.; Sun, Y.; Sun, G.; Peng, X.-P.; Lou, H.-X. Heptaketides from the Endophytic Fungus Pleosporales sp. F46 and Their Antifungal and Cytotoxic Activities. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 12913–12920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumarihamy, M.; Ferreira, D.; Croom, E.M.; Sahu, R.; Tekwani, B.L.; Duke, S.O.; Khan, S.; Techen, N.; Nanayakkara, N.P.D. Antiplasmodial and Cytotoxic Cytochalasins from an Endophytic Fungus, Nemania sp. UM10M, Isolated from a Diseased Torreya Taxifolia Leaf. Molecules 2019, 24, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, W.; Xu, Y.; Fu, P.; Zuo, M.; Liu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, W. Cytotoxic Indolyl Diketopiperazines from the Aspergillus sp. GZWMJZ-258, Endophytic with the Medicinal and Edible Plant Garcinia Multiflora. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 10660–10666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-X.; Li, Z.-H.; Ai, H.-L.; Li, J.; He, J.; Zheng, Y.-S.; Feng, T.; Liu, J.-K. Cytotoxic 19,20-Epoxycytochalasans from Endophytic Fungus Xylaria Cf. Curta. Fitoterapia 2019, 137, 104253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Amorim, M.R.; Hilário, F.; Junior, F.M. dos S.; Junior, J.M.B.; Bauab, T.M.; Araújo, A.R.; Carlos, I.Z.; Vilegas, W.; Santos, L.C. dos New Benzaldehyde and Benzopyran Compounds from the Endophytic Fungus Paraphaeosphaeria sp. F03 and Their Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activities. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, T.; Xu, L.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.-H.; Xia, T.; Yang, D.-F.; Chen, Y.-M.; Yang, X.-L. Three New α-Pyrone Derivatives from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Penicillium Ochrochloronthe and Their Antibacterial, Antifungal, and Cytotoxic Activities. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 21, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Hu, Y.-W.; Qu, W.; Chen, M.-H.; Zhou, L.-S.; Bi, Q.-R.; Luo, J.-G.; Liu, W.-Y.; Feng, F.; Zhang, J. Cytotoxic and Neuroprotective Activities of Constituents from Alternaria Alternate, a Fungal Endophyte of Psidium Littorale. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 90, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tao, Y.; She, Z. Cytotoxic Isocoumarin Derivatives from the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus sp. HN15-5D. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2019, 42, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Hu, L.; Shi, Z.; Sun, W.; Yue, D.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Ren, Z.; Zuo, Z.; Peng, G.; et al. Two Metabolites Isolated from Endophytic Fungus Coniochaeta sp. F-8 in Ageratina Adenophora Exhibit Antioxidative Activity and Cytotoxicity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 2840–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalli, Y.; Arora, P.; Khan, S.; Malik, F.; Riyaz-Ul-Hassan, S.; Gupta, V.; Ali, A. Isolation, Structural Modification of Macrophin from Endophytic Fungus Phoma Macrostoma and Their Cytotoxic Potential. Med. Chem. Res. 2019, 28, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Ai, C.-Z.; Song, Y.-C.; Wang, F.-W.; Jiao, R.-H.; Zhang, A.-H.; Man, H.-Z.; Tan, R.-X. Cytotoxic Trichothecene Macrolides Produced by the Endophytic Myrothecium Roridum. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubiani, J.R.; Oliveira, M.C.S.; Neponuceno, R.A.R.; Camargo, M.J.; Garcez, W.S.; Biz, A.R.; Soares, M.A.; Araujo, A.R.; da Bolzani, V.S.; Lisboa, H.C.F.; et al. Cytotoxic Prenylated Indole Alkaloid Produced by the Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus Terreus P63. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 32, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, L.; You, Y.-X.; Su, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Fan, Y.; Hu, F.; Xu, Y.-K.; Zhang, C.-R. Two Spiroketal Derivatives with an Unprecedented Amino Group and Their Cytotoxicity Evaluation from the Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis Flavidula. Fitoterapia 2019, 135, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, M.-H.; Zhuo, F.; Gao, N.; Cheng, X.-B.; Wang, X.-B.; Pei, Y.-H.; Kong, L.-Y. Seven New Cytotoxic Phenylspirodrimane Derivatives from the Endophytic Fungus Stachybotrys Chartarum. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 3520–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.-H.; Han, X.-H.; Qin, L.-L.; He, J.-L.; Cao, Z.-X.; Gu, Y.-C.; Guo, D.-L.; Deng, Y. Isochromanes from Aspergillus Fumigatus, an Endophytic Fungus from Cordyceps Sinensis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 1870–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elissawy, A.M.; Ebada, S.S.; Ashour, M.L.; El-Neketi, M.; Ebrahim, W.; Singab, A.B. New Secondary Metabolites from the Mangrove-Derived Fungus Aspergillus sp. AV-2. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 29, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-M.; Ju, C.-X.; Li, G.; Sun, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y.-X.; Peng, X.-P.; Lou, H.-X. Dimeric 1,4-Benzoquinone Derivatives with Cytotoxic Activities from the Marine-Derived Fungus Penicillium sp. L129. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, B.; Tong, Q.; Lin, S.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Cytotoxic Butenolides and Diphenyl Ethers from the Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis sp. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 29, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, C.; Cheng, L.; Wei, M.; Dai, C.; He, Y.; Gong, J.; Zhu, R.; Li, X.-N.; Liu, J.; et al. Emeridones A–F, a Series of 3,5-Demethylorsellinic Acid-Based Meroterpenoids with Rearranged Skeletons from an Endophytic Fungus Emericella sp. TJ29. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 1534–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Tan, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W. Four New Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Diaporthe Lithocarpus A740. Fitoterapia 2019, 137, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmani, A.; Teponno, R.B.; Arzanlou, M.; Surup, F.; Helaly, S.E.; Wittstein, K.; Praditya, D.F.; Babai-Ahari, A.; Steinmann, E.; Stadler, M. Cytotoxic, Antimicrobial and Antiviral Secondary Metabolites Produced by the Plant Pathogenic Fungus Cytospora sp. CCTU A309. Fitoterapia 2019, 134, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-J.; Yang, S.-S.; Wu, M.-D.; Chang, H.-H.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Hsieh, S.-Y.; Chen, J.-J.; Wu, H.-C. Isolation and Structure Elucidation of Secondary Metabolites From an Endophytic Fungus Annulohypoxylon Ilanense. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Heering, C.; Janiak, C.; Müller, W.E.G.; Akoné, S.H.; Liu, Z.; Proksch, P. Sesquiterpenoids from the Endophytic Fungus Rhinocladiella Similis. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, J.; Guo, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W. Three New Diterpenes and Two New Sesquiterpenoids from the Endophytic Fungus Trichoderma Koningiopsis A729. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 86, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-X.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.-H.; Li, J.; Ai, H.-L.; Liu, J.-K. Cytochalasins D1 and C1, Unique Cytochalasans from Endophytic Fungus Xylaria Cf. Curta. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 150952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Tang, T.; Wang, L.-Y.; He, B.; Gao, K. Absolute Configuration and Biological Activities of Meroterpenoids from an Endophytic Fungus of Lycium Barbarum. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 2229–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, F.; Vansteelandt, M.; Triastuti, A.; Jargeat, P.; Jacquemin, D.; Graton, J.; Mejia, K.; Cabanillas, B.; Vendier, L.; Stigliani, J.-L.; et al. Thiodiketopiperazines with Two Spirocyclic Centers Extracted from Botryosphaeria Mamane, an Endophytic Fungus Isolated from Bixa Orellana L. Phytochemistry 2019, 158, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lin, J.; Niu, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, L. Pestalotiones A–D: Four New Secondary Metabolites from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis Theae. Molecules 2020, 25, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, X.; Müller, W.E.G.; Meier, D.; Kalscheuer, R.; Guo, Z.; Zou, K.; Umeokoli, B.O.; Liu, Z.; Proksch, P. Polyketide Derivatives from Mangrove Derived Endophytic Fungus Pseudopestalotiopsis Theae. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdou, R.; Shabana, S.; Rateb, M.E. Terezine E, Bioactive Prenylated Tryptophan Analogue from an Endophyte of Centaurea Stoebe. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Oliveira Filho, J.W.G.; Andrade, T.d.J.A.d.S.; de Lima, R.M.T.; Silva, D.H.S.; dos Reis, A.C.; Santos, J.V.d.O.; de Meneses, A.-A.P.M.; de Carvalho, R.M.; da Mata, A.M.O.; de Alencar, M.V.O.B.; et al. Cytogenotoxic Evaluation of the Acetonitrile Extract, Citrinin and Dicitrinin-A from Penicillium Citrinum. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbaey, M.; Tanaka, C.; Miyamoto, T. Allantopyrone E, a Rare α-Pyrone Metabolite from the Mangrove Derived Fungus Aspergillus Versicolor. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Deng, Q.; Sun, M.; Xu, J. Cytospyrone and Cytospomarin: Two New Polyketides Isolated from Mangrove Endophytic Fungus, Cytospora sp. Molecules 2020, 25, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Tao, L.; Qiao, Y.; Sun, W.; Xie, S.; Shi, Z.; Qi, C.; Zhang, Y. New Cytotoxic Secondary Metabolites against Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells from the Hypericum Perforatum Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus Terreus. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Q.; Dong, Q.-J.; Xu, K.; Yuan, X.-L.; Liu, X.-M.; Zhang, P. Cytotoxic Xanthones from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Paecilamyces sp. TE-540. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 35, 6134–6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Fan, W.; Guo, H.; Huang, C.; Yan, Z.; Long, Y. Two New Secondary Metabolites from the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Pleosporales sp. SK7. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 2919–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Yin, R.; Zhou, Z.; Gu, G.; Dai, J.; Lai, D.; Zhou, L. Eremophilane-Type Sesquiterpenoids From the Endophytic Fungus Rhizopycnis Vagum and Their Antibacterial, Cytotoxic, and Phytotoxic Activities. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 596889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Stuhldreier, F.; Schmitt, L.; Wesselborg, S.; Guo, Z.; Zou, K.; Mándi, A.; Kurtán, T.; Liu, Z.; Proksch, P. Induction of New Lactam Derivatives From the Endophytic Fungus Aplosporella Javeedii Through an OSMAC Approach. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Tan, H.; Zhang, W. Trichothecene Macrolides from the Endophytic Fungus Paramyrothecium Roridum and Their Cytotoxic Activity. Fitoterapia 2020, 147, 104768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.; Kwon, H.E.; Baek, J.Y.; Jang, D.S.; Kim, S.; Nam, S.-J.; Lee, D.; Kang, K.S.; Shim, S.H. Colletotrichalactones A-Ca, Unusual 5/6/10-Fused Tricyclic Polyketides Produced by an Endophytic Fungus, Colletotrichum sp. JS-0361. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 105, 104449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riga, R.; Happyana, N.; Quentmeier, A.; Zammarelli, C.; Kayser, O.; Hakim, E.H. Secondary Metabolites from Diaporthe Lithocarpus Isolated from Artocarpus Heterophyllus. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 2324–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhu, Y.-X.; Peng, C.; Li, J. Two New Sterol Derivatives Isolated from the Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus Tubingensis YP-2. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 3277–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Jia, M.; Ming, Q.-L.; Yue, W.; Rahman, K.; Qin, L.-P.; Han, T. Endophytic Fungi with Antitumor Activities: Their Occurrence and Anticancer Compounds. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 42, 454–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cragg, G.M.; Newman, D.J. Plants as a Source of Anti-Cancer Agents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ling-hua, M.; Zhi-yong, L.; Pommier, Y. Non-Camptothecin DNA Topoisomerase I Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2003, 3, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommier, Y. Topoisomerase I Inhibitors: Camptothecins and Beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidle, A.M.; Myers, A.G. An Enantioselective, Modular, and General Route to the Cytochalasins: Synthesis of L-696,474 and Cytochalasin B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 12048–12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Svoboda, G. Alkaloids of Vinca Rosea (Catharanthus Roseus). IX. Extraction and Characterization of Leurosidine and Leurocristine. Subj. Strain Bibliogr. 1961, 24, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kawada, M.; Inoue, H.; Ohba, S.-I.; Masuda, T.; Momose, I.; Ikeda, D. Leucinostatin A Inhibits Prostate Cancer Growth through Reduction of Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Expression in Prostate Stromal Cells. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.S.; Sohrab, H.; Rana, S.; Hasan, C.M.; Jamshidi, S.; Rahman, K.M. Cytotoxic Naphthoquinone and Azaanthraquinone Derivatives from an Endophytic Fusarium Solani. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 1173–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kharwar, R.N.; Mishra, A.; Gond, S.K.; Stierle, A.; Stierle, D. Anticancer Compounds Derived from Fungal Endophytes; Their Importance and Future Challenges. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 1208–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.C.; Taylor, H.L.; Wall, M.E.; Coggon, P.; McPhail, A.T. Plant Antitumor Agents. VI. Isolation and Structure of Taxol, a Novel Antileukemic and Antitumor Agent from Taxus Brevifolia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2325–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.M.; Kingston, D.G.I.; Newman, D.J. (Eds.) Anticancer Agents from Natural Products, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-429-13085-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Yuan, X.-L.; Du, Y.-M.; Wang, B.-G.; Zhang, Z.-F. Antifungal Prenylated Diphenyl Ethers from Arthrinium Arundinis, an Endophytic Fungus Isolated from the Leaves of Tobacco (Nicotiana Tabacum L.). Molecules 2018, 23, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, Y.; Stuhldreier, F.; Schmitt, L.; Wesselborg, S.; Wang, L.; Müller, W.E.G.; Kalscheuer, R.; Guo, Z.; Zou, K.; Liu, Z.; et al. Sesterterpenes and Macrolide Derivatives from the Endophytic Fungus Aplosporella Javeedii. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell Lines | Cell Lines | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A2780S | Ovarian tumor cell line | Int-407 | Human intestine cancer |

| A2058 | Human melanoma | Jurkat | T cell leukemia |

| A549 | Lung carcinoma epithelial | KB | Human nasopharyngeal epidermoid tumor |

| A431 | Skin carcinoma | K562 | Human leukemia cells |

| ACHN | Renal cells | L5178Y | Mouse lymphoma cells |

| AsPC-1 | Human pancreatic cancer cells | MIA Pa Ca-2 | Pancreatic carcinoma |

| B16F10 | Skin carcinoma | MiaPaka-2 | Pancreatic cancer |

| BC | Human breast cancer cell line | MDA-MB-231 | Breast cancer cell line |

| BC-1 | Breast cancer | MDA-MB-435 | Human breast cancer cell line |

| BEL-7402 | Human hepatocellular carcinoma/human hepatoma cell line | MFC | Gastric cancer cells in mice |

| BEL-7404 | Human hepatocellular carcinoma/human hepatoma cell line | MCF-7 | Breast cancer cell line |

| BGC-823 | Gastric carcinoma | MOLT-4 | Lymphoblastic leukemia |

| BT-220 | Breast cancer cell line | MRC-5 | Fibroblast-like fetal lung cells |

| BT474 | Human breast cancer | MV4-11 | Human FLT3-ITD mutant AML cell line |

| CHO | Chinese hamster ovary | NCI-H187 | Human small-cell lung cancer |

| DU145 | Human prostate carcinoma | NCI-H460 | Non-small-cell lung cancer |

| EAC | Ehrlich ascites carcinoma | NEC | Colorectal neuroendocrine cell carcinoma |

| H116 | Human colon adenocarcinoma | OVCAR-5 | Human ovarian cancer |

| HeLa | Cervical cancer | PANC-1 | Human pancreatic carcinoma |

| HEp-2 | Human liver cancer | P388 | Murine leukemia cells |

| HepG2 | Human hepatocellular liver carcinoma | PC-3 | Prostate cancer |

| Hep3B | Human hepatoma cell line | PC-3 M | Metastatic prostate cancer |

| HM02 | Human gastric carcinoma | RAW264.7 | Mouse macrophage cell |

| HL-60 | Human promyelocytic leukemia cell line | SF-268 | CNS glioma |

| HL251 | Human lung cancer | SW480 | Human colon cancer cells |

| HL-7702 | Normal hepatocyte | SW-620 | Colon tumor cell line |

| HLK 210 | Human leukemia | SW1116 | Human colon cancer cell line |

| HCT-8 | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma | SW1990 | Human pancreatic cancer cells |

| HCT-116 | Colon tumor cell line | T24 | Bladder carcinoma |

| H22 | Hepatic cancer cells in mice | T47D | Breast cancer |

| H1975 | Non-small-cell lung cancer cells/human lung adenocarcinoma | THP-1 | Human monocytic cell line |

| H522-T1 | Non-small cell lung cancer | WI-38 | Normal human fibroblast cells |

| HT-29 | Human colon cancer line | U2OS | Human osteosarcoma cells |

| Compounds | Chemical Class | Fungal Endophytes | Host Medicinal Plant | Activity Against Cell Lines | IC50 Values | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leucinostatin A | Peptide | Acremonium spp. | Taxus baccata twig | BT-20 | 2 nM (LD50) | [14] |

| Allantopyrone A | α-Pyrone | Allantophomopsis l. KS-97 | A549 cells, HL-60 | ˃32, 0.32 µM | [15] | |

| Alternariol, Altenusin, Alternariol 5-O-sulfate, Alternariol 5-O-methyl ether, Desmethylaltenusin | Polyketide | Alternaria spp | Polygonum senegalense leaves | L5178Y | ˂1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−5, 1 × 10−5, 1 × 10−5, 1 × 10−5 g/mL | [16] |

| Lapachol | Naphtho-quinone | Alternaria spp. | Tabebuia argentea leaf | DU145, HepG2, Hep3B & MCF-7 (β-Lapachone) | 3.5, 3.5, 3.5 & 5 µM | [17,18,19,20,21,22] |

| Resveratrodehydes A & B | Stilbenoid (Resveratrol dervatives) | Alternaria spp. R6 | Myoporum bontioides root | MDA-MB-435, HCT-116 | ˂10 µM | [23] |

| Alterporriol K, Alterporriol L | Quinones | Alternaria spp. ZJ9-6B | Aegiceras corniculatum | MDA-MB-435, MCF-7 | 26.97, 29.11 & 13.11, 20.04 µM | [24] |

| Alternariol-10-methyl ether | Polyketide | Alternaria a. | Capsicum annum | HL-60, A549, PC-3, HeLa, A431, MiaPaka-2 and T47D | 85, ˃100, ˃100, ˃100, 95, ˃100 and ˃100 µM | [25] |

| Camptothecine (CPT), 9-methoxy CPT, 10-hydroxy CPT | Alkaloids | Alternaria a. | Miquelia dentata fruit and seed regions | HCT-116, SW-480, MCF-7 | 6.59, 7.2, 10.24 µg/mL (crude fungal ethyl acetate extract) | [26] |

| Chrysin (5,7-dihydroxy flavone) | Flavone | Alternaria a. (KT380662) | Passiflora incarnata leaves | MCF-7 | 34.066 µg/mL | [27] |

| Alternariol 9-methyl ether | Dibenzopyranone | Alternaria a. | Camellia sinensis branches | U2OS | 28.3 µM | [28] |

| Lapachol | Naphtho-quinone | Alternaria a. | Tabebuia argentea bark, leaf and stem | DU145, HepG2, Hep3B & MCF-7 (β-Lapachone) | 3.5, 3.5, 3.5 & 5 µM | [17,18,19,20,21,22] |

| (6aR,6bS,7S)-3, 6a, 7,10-tetrahydroxy- 4,9-dioxo-4, 6a, 6b, 7, 8,9-hexahydroperylene | Perylenes | Alternaria t. | Erythrophleum fordii bark | HCT-8 | 1.78 µM | [29] |

| 1. Flavasperone, 2. Rubrofusarin B 3. Fonsecinone D | Naphthopyrones | Aspergillus sp. | Limonia acidissima seeds | 1. Hep 3B and U87 MG 2. SW1116 3. SMMC-7721 and A549 | 1. Between 19.92 and 47.98 µM 2. 4.5 µg/mL 3. ˃10 µg/mL | [30] |

| Brefeldin A | Lactone | Aspergillus c. | Torreya grandis bark | HL-60, KB, Hela, MCF-7 and Spc-A-1 | 1.0–10.0 ng/mL | [31] |

| 9-Deacetoxy fumigaclavine C | Alkaloids | Aspergillus f. | Cynodon dactylon stem | K562 | 3.11 µM | [32] |

| 1. Fumitremorgin D, 2. 4,8,10,14-tetramethyl-6-acetoxy-14-[16-acetoxy-19-(20,21- dimethyl)-18-ene]-phenanthrene-1-ene-3,7-dione 3. 12,13-dihydroxy-fumitremorgin C 4. Verruculogen | Alkaloids | Aspergillus f. | Diphylleia sinensis mainly roots, rhizomes | HepG2 | 1. 47.5 µM 2. 139.9 µM 3. 4.5 µM 4. 9.8 µM | [33] |

| 2,14-Dihydrox-7-drimen-12,11-olide | Sesquiterpenes | Aspergillus g. | Ipomoea batatas plant | Hep-G2, MCF-7 | 61, 41.7 µg/mL | [34] |

| Nigerapyrones B, D & E Asnipyrones A | Pyrones | Aspergillus n. MA-132 | Avicennia marina plant | HepG2, MCF-7, A549, SW1990, MDA-MB-231 | 86, 105, 43, 38, 48 µM | [35] |

| Rubrofusarin B | Naphtho-γ-pyrones | Aspergillus n. | Cynodon dactylon | SW1116 | 4.5 µg/mL | [36] |

| Lapachol | Naphtho-quinone | Aspergillus n. | Tabebuia argentea leaves | DU145, HepG2, Hep3B & MCF-7 (β-Lapachone) | 3.5, 3.5, 3.5 & 5 µM | [17,18,19,20,21,22] |

| 1. Sequoiatones A & B 2. Sequoiamonascin A & B | Polyketide | Aspergillus p. | Sequoia sempervirens inner bark | 1. BC 2. MCF7, NCI-H460, SF-268 | 1. 4 to 10 µM 2. 19 × 10−4, 4 × 10−4, 15 × 10−4 M | [37,38] |

| Butyrolactone I and Butyrolactone V | Butenolide | Aspergillus t.—F7 | Hyptis suaveolens | MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 | 34.4, 17.4 & 22.1, 31.9 µM | [39] |

| Terrein | Aspergillus t. JAS-2 | Achyranthus aspera | A-549 | 121.9 µg/mL | [40] | |

| 1. Violaceoid A, 2. Violaceoid C, Violaceoid D, 3. Violaceoid F | Hydroquinones | Aspergillus v. | Wild Moss (Bryophyta unidentified species) | 1. HeLa, MCF-7, Jurkat, MOLT-4, HCT116, RAW264.7 2. Jurkat, MOLT-4 3. HCT116, RAW264.7 | 1. 24.6, 14.8, 3.1, 3.0, 5.8, 5.6 µM (LD50) 2. 8.2, 5.9 & 8.3, 6.2 µM (LD50) 3. 6.4, 6.5 µM (LD50) | [41] |

| Taxol | Terpene | Bartalinia r. | Aegle marmelos leaves | BT 220, H116, Int 407, HL 251 and HLK 210 | - | [42] |

| Depsidone 1 | Depsidone | Pleosporales (BCC 8616) | unidentified plant leaf of the Hala-Bala forest origin | KB, BC | 6.5, 4.1 µg/mL | [43] |

| 1. Diepoxin δ, Palmarumycin C8 2. Diepoxins κ & ζ | Spirobis-naphthalenes | Berkleasmium spp. | Dioscorea zingiberensis | 1. HCT-8, Bel-7402, BGC-823, A 549, A2780 2. Bel-7402 and A 549 | 1. 1.7, 3.3, 3.3, 3.2, 5.8 & 4.2, 2.5, 2.6, 1.6, 1.3 µM 2. 6.4, 8.7 & 5.1, 8.8 µM | [44] |

| Verticillin D | Peptide | Bionectria o. | Sonneratia caseolaris Inner leaf tissues | L5178Y | <0.1 µg/mL (EC50) | [45] |

| Ophiobolin A | Sesterterpenoid | Bipolaris s. | Unidentified | MDA-MB-231 | 0.4–4.3 µM | [46] |

| 1. Stemphyperylenol 2. Altenuene | 1. Polyketide 2. Mycotoxin | Botryosphaeria d. KJ-1 | Melia azedarach stem bark | HCT116 | 3.13 µM | [47] |

| Botryorhodine A and B | Depsidone | Botryosphaeria r. | Bidens pilosa stem | HeLa, K-562 | 96.97, 36.41 & 0.84, 0.003 µM (CC50) | [48] |

| Cercosporene F | Guanacastane Diterpenes | Cercospora spp. | Fallopia japonica leaves | HeLa, A549, MCF-7, HCT116 and T24 | 19.3, 29.7, 46.1, 21.3 & 8.16 µM | [49] |

| Ceriponol F, Ceriponol G, Ceriponol K | Sesquiterpenes | Ceriporia l. | Huperzia serrata | HeLa, HepG2, SGC7901 | 173.2, 32.3, 77.5; 185.1, ˃500.0, ˃500.0 & 47.8, 35.8, 60.2 µM | [50] |

| Cochliodinol, Isocochliodinol | Quinones | Chaetomium spp. | Salvia officinalis Stem | L5178Y | 7.0, 71.5 µg/mL (EC50) | [51] |

| Chaetocochin C | Diketopiperazine | Chaetomium spp. | Cymbidium goeringii root | SW-480 | 0.63 µM | [52] |

| Chaetocochin G | Indole diketo-piperazines | Chaetomium spp. 88194 | Cymbidium goeringii | MCF-7 | 8.3 mg/mL | [53] |

| Chaetominine | Alkaloids | Chaetomium spp. IFB-E015 | Adenophora axilliflora leaves | K562, SW1116 | 21.0, 28.0 nM | [54] |

| Radicicol | Lactone | Chaetomium c. | Ephedra fasciculate stem | MCF-7 | 0.03 µM | [55] |

| Chaetoglobosin X | Alkaloids | Chaetomium g. L18 | Curcuma wenyujin | H22, MFC | 3.125, 6.25 µg/mL | [56] |

| Chaetoglobosin C, E, F & U, Penochalasin A | Alkaloids | Chaetomium g. IFB-E019 | Imperata cylindrica stem | KB cell line | 34.0, 40.0, 48.0 & 16.0, 48.0 µM | [57] |

| Globosumone A & B | Ester | Chaetomium g. | Ephedra fasciculata | NCI-H460, MCF-7, SF-268, MIA Pa Ca-2, WI-38 | 6.50, 21.30, 8.80, 10.60, 13.00 & 24.80, 21.90, 29.10, 30.20, 14.20 µM | [58] |

| Chaetoglobosins A, Fex, Fa & 20-dihydrochaetoglobosin | Alkaloids (cytochalasan mycotoxins) | Chaetomium g. | Ginkgo biloba leaves | HCT116 | 3.15, 4.43, 5.85, 8.44 µM | [59] |

| Anhydrofusarubin and methyl ether of Fusarubin | Naphtho-quinones | Cladosporium spp. | Rauwolfia serpentina leaves | K-562 | 3.97 & 3.58 µg/mL | [7] |

| Taxol | Diterpene | Cladosporium c. | Taxus media inner bark | MCF-7, BT220, H116, INT-407, HL251, HLK210 | 0.005 to 5 µM | [60,61] |

| Taxol | Diterpene | Cladosporium o. | Aegle marmelos, Coccinia indica and Moringa oleifera | HCT 15, T47D | 3.5, 2.5 µM | [62,63] |

| Taxol | Diterpene | Colletotrichum c. | Capsicum annuum fruit | MCF-7, HL 251, HLK 210, BEL7402 | 0.005 to 5 µM | [64,65] |

| Tyrosol C | # | Colletotrichum g. | Pandanus amaryllifolius leaves | A549, HT29, HCT116 | - | [66] |

| Deacetylcytochalasin C and Zygosporin D | Cytochalasins | Cordyceps t. | unidentified | 95-D | 3.67 & 4.04 µM | [67] |

| 1. Cytospolide P, 2. Cytospolide Q | Lactones | Cytospora spp. | Ilex canariensis | 1. A-549, QGY, U973 2. A-549 | 1. 2.05, 15.82, 28.26 µg/mL 2. 10.55 µg/mL | [68] |

| Xylarolide | # | Diaporthe t. GG3F6. | Glycyrrhiza glabra rhizomes | T47D | 7 µM | [69] |

| Taxol | Diterpenes | Didymostilbe spp. | Taxus chinensis var. mairei old inner bark | MCF-7, HL 251, HLK 210, BEL7402 | 0.005 to 5 µM | [64,65] |

| Camptothecin | Alkaloids | Entrophospora i. | Nothapodytes foetida inner bark | A-549, HEP-2, OVCAR-5 | - | [11] |

| 1. Eutypellin A, 2. ent-4(15)-eudesmen-11-ol-1-one | 1. γ-Lactone 2. Sesquiterpene | Eutypella sp. BCC 13199 | Etlingera littoralis | NCI-H187, MCF7, KB, Vero cells | 1. 12, 84, 38, 88 µM 2. 11, 20, 32, 32 µM | [70] |

| Camptothecine (CPT), 9-methoxy CPT, 10-hydroxy CPT | Alkaloids | Fomitopsis spp. | Miquelia dentata fruit and seed regions | HCT-116, SW-480, MCF-7 | 5.63, 23.5, 10.32 µg/mL (crude fungal ethyl acetate extract) | [26] |

| Beauvericin | Depsipeptide | Fusarium o. | Cinnamomum kanehirae bark | PC-3, PANC-1, A549 | 49.5, 47.2, 10.4 µM | [71] |

| Taxol | Diterpenes | Fusarium o. | Rhizomphora annamalayana leaves | BT220, HL251, HLK 210 | 0.005 to 5 µM | [72,73] |

| Vincristine | Alkaloids | Fusarium o. | Catharanthus roseus inner bark | HeLa, MCF7, A549, U251, A431 & HEK293 | 4.2, 4.5, 5.5, 5.5, 5.8 µg/mL | [74,75] |

| Beauvericin | Depsipeptide | Fusarium o. | Cinnamomum kanehirae bark | PC-3, PANC-1, A549 | 49.5, 47.2, 10.4 µM | [71] |

| Beauvercin | Depsipeptide | Fusarium o. | Ephedra fasciculata root | NCI-H460, MIA Pa Ca-2, MCF-7, SF-268, PC-3 M, MDA-MB-231, MRC-5, Hep-G2 | 1.41, 1.66, 1.81, 2.29, 3.0, 5.0, 4.7–5.0, 8.8–22.2 µM | [76,77] |

| Beauvercin | Depsipeptide | Fusarium o. EPH2RAA | Cylindropuntia echinocarpus stem | NCI-H460, MIA Pa Ca-2, MCF-7, SF-268, PC-3 M, MDA-MB-231 | 1.41, 1.66, 1.81, 2.29, 3.0, 5.0 µM | [77] |

| Bikaverin | Polyketide | Fusarium o. CECIS | Cylindropuntia echinocarpus stem | NCI-H460, MIA Pa Ca-2, MCF-7, SF-268, EAC, leukemia L 5178, sarcoma 37 | 1.41, 1.66, 1.81, 2.29, 0.5, 1.4, 4.2 µg/mL (ED50) | [77,78] |

| Camptothecin (CPT) and 9-methoxy CPT | Alkaloids | Fusarium s. (MTCC 9667 and MTCC 9668) | Apodytes dimidiata | HCT-116, SW-480, MCF-7 | 7, 8.5, 8 & 7, 8.5, 8 µg/mL | [10,26] |

| Podophyllotoxin | Lignans | Fusarium s. | Podophyllum hexandrum roots | # | - | [79] |

| Camptothecine (CPT), 9-methoxy CPT, 10-hydroxy CPT | Alkaloids | Fusarium s. | Camptotheca acuminata inner bark | OVCAR-5, HCT-116 SW-480, MCF-7 | 7, 8.5, 8 & 7, 8.5, 8 µg/mL | [26,80] |

| Gliocladicillins A & B | Epipolythiodi-oxopiperazines | Gliocladium spp. XZC04-CC-302 | Cordyceps sinensis bark. | HeLa, HepG2, MCF-7 | 0.50, 0.50,0.20 µg/mL (GI50) | [81] |

| Guignarenone A | Tricyclo-alternarene | Guignardia b. PSU-G11 | Garcinia hombroniana leaves | KB, Vero | 0.38, 2.24 µM | [82] |

| Guignardones Q & S | Meroterpenoids | Guignardia m. A348 | Smilax glabra leaves | MCF-7 | 83.7 & 92.1 µM | [83] |

| Cajanol (5-hydroxy-3-(4- hydroxy-2-methoxyphenyl)-7-methoxychroman-4-one) | Flavonoids | Hypocrea l. | Cajanus cajan roots, stems and leaves | 1. A549 2. PC-3, HT-29, HepG2 | 1. 20.5 µg/mL after 72 h treatment, 24.6 µg/mL after 48 h; and 32.8 µg/mL after 24 h 2. 29.8, 21.4, 33.6 µg/mL (Fungal crude extract) | [84] |