Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Model of Neuroinflammation: Mechanisms of Action, Research Application and Future Directions for Its Use

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Lipopolysaccharide—Insights in the Structure

3. Cellular Recognition of LPS

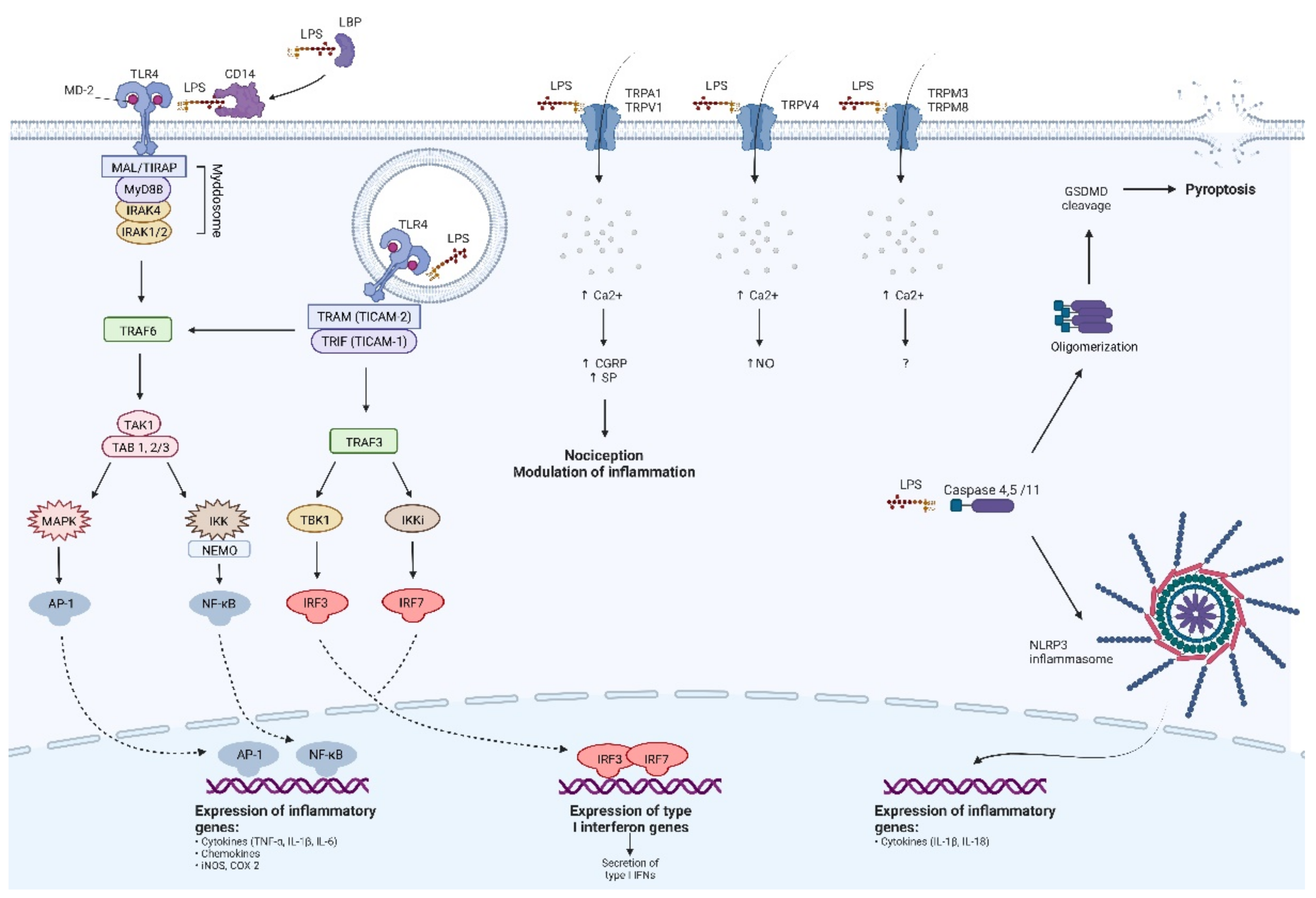

3.1. Toll-like Receptor 4

3.2. TLR4-Independent Pathways of LPS Detection

4. The Utility of LPS Inflammation Model in the Research Field

5. Technical Aspects of LPS Model Execution—Focus on AD and PD Modeling

6. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Dysfunction

6.1. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Glucocorticoids

6.2. Antidiabetic Drugs

6.3. Dexmedetomidine

6.4. Minocycline

6.5. Drugs Currently Registered in AD

6.6. Monoclonal Antibodies in AD and PD

7. Future Outlook

7.1. Nature-Derived Substances

7.2. Novel Compounds

8. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | amyloid-β |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Akt | protein kinase B |

| AMPK | 5'AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AP | 1-activator protein-1 |

| Ara4N | 4-amino-arabinose |

| BAY61-3606 | 2-[[7-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)imidazo[1,2-c]pyrimidin-5-yl]amino] pyridine-3-carboxamide |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| CARD | caspase recruitment domain |

| CD-14 | cluster of differentiation-14 |

| CD-36 | cluster of differentiation-36 |

| CGRP | calcitonin gene-related peptide |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| COX | cyclooxygenase |

| CR | complement receptor |

| CREB | cAMP-response element binding protein |

| C1q | complement component 1q |

| DAMP | damage-associated molecular pattern |

| DYRK1A | tyrosine phosphorylation regulated kinase 1A |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GC | glucocorticoid |

| GSDMD | gasdermin-D |

| GSK3 | glycogen synthase kinase 3 |

| GTS-21 | 3-(2,4-dimethoxybenzylidene)-anabaseine, DMXBA |

| Iba-1 | ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 |

| IKK | Iκβ kinase complex |

| IKKi | IKK inducible kinase |

| IL | interleukin |

| iNOS | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IRAK | interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase |

| IRF | interferon regulatory factor |

| LBP | lipopolysaccharide-binding protein |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| LRR | leucine-rich repeat domain |

| MAL | MyD88- adopter-like protein |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MIP | macrophage inflammatory protein |

| MWM | Morris water maze test |

| MyD88 | myeloid differentiation primary response protein |

| NAD | novel arm discrimination task |

| NEMO | NF-κB essential modulator |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-Κb |

| NFT | intracellular neurofibrillary tangles |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| NLR | NOD-like receptor |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NOR | novel object recognition task |

| NSAID | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| OFT | open field task |

| PAMP | pathogen-associated molecular pattern |

| PAR1 | protease-activated receptor 1 |

| PAT | passive avoidance test |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| PPAR-γ | peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor gamma |

| PRR | pattern recognition receptor |

| PT | pole test |

| RAGE | receptor for advanced glycation end-products |

| RIP1/RIPK1 | receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 |

| RLR | retinoic acid inducible gene-I-like receptor |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SN | substantia nigra |

| SNpc | substantia nigra pars compacta |

| SR | scavenger receptor |

| SP | substance P |

| TAB | TAK1 binding protein |

| TAK1 | transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1 |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding kinase 1 |

| TIR | Toll/IL-1 receptor domain |

| TIRAP | TIR domain containing adaptor protein |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TRAF | TNF-receptor associated factor |

| TRAM | TRIF-related adaptor molecule |

| TRIF | Toll/interleukin-1-receptor domain- containing adaptor inducing interferon β |

| TRP | transient receptor potential |

| TRPA1 | transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 |

| TRPM3 | transient receptor potential melastatin 3 |

| TRPM8 | transient receptor potential melastatin 8 |

| TRPV1 | transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 |

| TRPV4 | transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 |

| TSPO | translocator protein |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Zhao, J.; Bi, W.; Xiao, S.; Lan, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Lu, D.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Neuroinflammation Induced by Lipopolysaccharide Causes Cognitive Impairment in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenbark, A.A.; Offner, H.; Matejuk, S.; Matejuk, A. Microglia and Astrocyte Involvement in Neurodegeneration and Brain Cancer. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudwarts, A.; Ramesha, S.; Gao, T.; Ponnusamy, M.; Wang, S.; Hansen, M.; Kozlova, A.; Bitarafan, S.; Kumar, P.; Beaulieu-Abdelahad, D.; et al. BIN1 Is a Key Regulator of Proinflammatory and Neurodegeneration-Related Activation in Microglia. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, H.D.E.; Hirst, W.D.; Wade-Martins, R. The Role of Astrocyte Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. Trends Neurosci. 2017, 40, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novianti, E.; Katsuura, G.; Kawamura, N.; Asakawa, A.; Inui, A. Atractylenolide-III Suppresses Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation via Downregulation of Toll-like Receptor 4 in Mouse Microglia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doens, D.; Fernández, P.L. Microglia Receptors and Their Implications in the Response to Amyloid β for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, F.; Ren, M.; Liu, X.; Xie, W.; Zhang, A.; Qian, M.; Mo, Y.; Wang, J.; Lv, Y. The PICK1/TLR4 Complex on Microglia Is Involved in the Regulation of LPS-Induced Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 100, 108116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo Qaid, E.Y.; Abdullah, Z.; Zakaria, R.; Long, I. Minocycline Protects against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Glial Cells Activation and Oxidative Stress Damage in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex (MPFC) of the Rat. Int. J. Neurosci. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, I.; Corrigan, F.; Zhai, G.; Zhou, X.-F.; Bobrovskaya, L. Lipopolysaccharide Animal Models of Parkinson’s Disease: Recent Progress and Relevance to Clinical Disease. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2020, 4, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, P.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; Feng, J.; Hong, J.-S. Early-Released Interleukin-10 Significantly Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Elicited Neuroinflammation In Vitro. Cells 2021, 10, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, M.; Torres, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Neuronal Mitochondria Modulation of LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 1756–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, R.; Wan Yaacob, W.M.H.; Othman, Z.; Long, I.; Ahmad, A.H.; Al-Rahbi, B. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Memory Impairment in Rats: A Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Physiol. Res. 2017, 66, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Münch, A.E.; Chung, W.-S.; Peterson, T.C.; et al. Neurotoxic Reactive Astrocytes Are Induced by Activated Microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, N.A.; Bahaidrah, K.A.; Mansouri, R.A.; Alsufiani, H.M.; Alghamdi, B.S. Investigation of the Optimal Dose for Experimental Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Recognition Memory Impairment: Behavioral and Histological Studies. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 21, 049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 700–789. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 9789241513487. [Google Scholar]

- Abyadeh, M.; Gupta, V.; Gupta, V.; Chitranshi, N.; Wu, Y.; Amirkhani, A.; Meyfour, A.; Sheriff, S.; Shen, T.; Dhiman, K.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Aducanumab, Zagotenemab and Pioglitazone as Targeted Treatment Strategies for Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, P.J.; Saini, V. Making the Case for the Accelerated Withdrawal of Aducanumab. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 87, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson Disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/parkinson-disease (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Mao, Q.; Qin, W.; Zhang, A.; Ye, N. Recent Advances in Dopaminergic Strategies for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revuelta, M.; Urrutia, J.; Villarroel, A.; Casis, O. Microglia-Mediated Inflammation and Neural Stem Cell Differentiation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Possible Therapeutic Role of KV1.3 Channel Blockade. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 868842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, G.R.; Wenzel, T.J.; Marshall, N.; Gates, E.J.; Klegeris, A. Targeting Toll-like Receptor 4 to Modulate Neuroinflammation in Central Nervous System Disorders. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2019, 23, 865–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borikar, S.P.; Dongare, S.I.; Danao, K.R. Reversal of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Learning and Memory Deficits by Agmatine in Mice. Int. J. Neurosci. 2022, 132, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouli, A.; Camacho, M.; Allinson, K.; Williams-Gray, C.H. Neuroinflammation and Protein Pathology in Parkinson’s Disease Dementia. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendranathan, A.; Su, L.; Mak, E.; Passamonti, L.; Hong, Y.T.; Arnold, R.; Vázquez Rodríguez, P.; Bevan-Jones, W.R.; Brain, S.A.E.; Fryer, T.D.; et al. Early Microglial Activation and Peripheral Inflammation in Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Brain 2018, 141, 3415–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavisse, S.; Goutal, S.; Wimberley, C.; Tonietto, M.; Bottlaender, M.; Gervais, P.; Kuhnast, B.; Peyronneau, M.-A.; Barret, O.; Lagarde, J.; et al. Increased Microglial Activation in Patients with Parkinson Disease Using [18F]-DPA714 TSPO PET Imaging. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2021, 82, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-S.; Heng, Y.; Yuan, Y.-H.; Chen, N.-H. Pathological α-Synuclein Exacerbates the Progression of Parkinson’s Disease through Microglial Activation. Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 265, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-C.; Lee, C.-Y.; Chern, Y.; Lin, C.-J. Amelioration of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Memory Impairment in Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter-2 Knockout Mice Is Accompanied by the Changes in Glutamatergic Pathways. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 96, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, B.; Ruiz, N. Function and Biogenesis of Lipopolysaccharides. EcoSal Plus 2018, 8, ecosalplus.ESP-0001-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knirel, Y.A.; Anisimov, A.P.; Kislichkina, A.A.; Kondakova, A.N.; Bystrova, O.V.; Vagaiskaya, A.S.; Shatalin, K.Y.; Shashkov, A.S.; Dentovskaya, S.V. Lipopolysaccharide of the Yersinia Pseudotuberculosis Complex. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, A.E.; Crawford, M.; Jasbi, P.; Fessler, S.; Sweazea, K.L. Lipopolysaccharide and the Gut Microbiota: Considering Structural Variation. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 849–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vello, P.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Zucchetta, D.; Zamyatina, A.; De Castro, C.; Molinaro, A. Lipopolysaccharide Lipid A: A Promising Molecule for New Immunity-Based Therapies and Antibiotics. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 230, 107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazgaeen, L.; Gurung, P. Recent Advances in Lipopolysaccharide Recognition Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, M.H.; Somprasong, N.; Schweizer, H.P.; Tuanyok, A. Lipid A Remodeling Is a Pathoadaptive Mechanism That Impacts Lipopolysaccharide Recognition and Intracellular Survival of Burkholderia Pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00360-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellati, T.J.; Sahay, B. Cells of Innate Immunity: Mechanisms of Activation. In Pathobiology of Human Disease; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 258–274. ISBN 9780123864574. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, T.; Kawai, T. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamiri, S.H.; Komlakh, K.; Ghaffari, M. Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) and Their Potential Therapeutic Applications in Diabetic Neuropathy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 102, 108398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, A.M.; Fults, J.B.; Patil, N.K.; Hernandez, A.; Bohannon, J.K. TLR Agonists as Mediators of Trained Immunity: Mechanistic Insight and Immunotherapeutic Potential to Combat Infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 622614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gern, O.L.; Mulenge, F.; Pavlou, A.; Ghita, L.; Steffen, I.; Stangel, M.; Kalinke, U. Toll-like Receptors in Viral Encephalitis. Viruses 2021, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nardo, D. Toll-like Receptors: Activation, Signalling and Transcriptional Modulation. Cytokine 2015, 74, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, A.; Ahuja, A.; Rahmawati, L.; Kim, H.G.; Woo, B.Y.; Hong, Y.D.; Hossain, M.A.; Zhang, Z.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, J.; et al. Caragana Rosea Turcz Methanol Extract Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Responses by Suppressing the TLR4/NF-ΚB/IRF3 Signaling Pathways. Molecules 2021, 26, 6660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Karch, J. Regulation of Cell Death in the Cardiovascular System. In International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 353, pp. 153–209. ISBN 9780128201350. [Google Scholar]

- Meseguer, V.; Alpizar, Y.A.; Luis, E.; Tajada, S.; Denlinger, B.; Fajardo, O.; Manenschijn, J.-A.; Fernández-Peña, C.; Talavera, A.; Kichko, T.; et al. TRPA1 Channels Mediate Acute Neurogenic Inflammation and Pain Produced by Bacterial Endotoxins. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonen, B.; Alpizar, Y.A.; Sanchez, A.; López-Requena, A.; Voets, T.; Talavera, K. Differential Effects of Lipopolysaccharide on Mouse Sensory TRP Channels. Cell Calcium 2018, 73, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałat, K.; Moniczewski, A.; Librowski, T. Transient Receptor Potential Channels-Emerging Novel Drug Targets for the Treatment of Pain. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 1409–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Lv, L.; Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Zhou, N.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, X.; et al. Nociceptor Neurons Are Involved in the Host Response to Escherichia Coli Urinary Tract Infections. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 3337–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, H.-K.; Lin, A.-H.; Perng, D.-W.; Lee, T.-S.; Kou, Y.R. Lung Epithelial TRPA1 Mediates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Lung Inflammation in Bronchial Epithelial Cells and Mice. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 596314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajna, Z.; Csekő, K.; Kemény, Á.; Kereskai, L.; Kiss, T.; Perkecz, A.; Szitter, I.; Kocsis, B.; Pintér, E.; Helyes, Z. Complex Regulatory Role of the TRPA1 Receptor in Acute and Chronic Airway Inflammation Mouse Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, M.P.; Boi, M.; Carta, A.; Murru, E.; Carta, G.; Banni, S.; Quartu, M. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Beta-Caryophyllene Mediated by the Involvement of TRPV1, BDNF and TrkB in the Rat Cerebral Cortex after Hypoperfusion/Reperfusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhou, W.; Dou, F.; Wang, C.; Yu, Z. TRPV1 Sustains Microglial Metabolic Reprogramming in Alzheimer’s Disease. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e52013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Fu, M.; Huang, Z.; Tian, X.; Li, J.; Pang, Y.; Song, W.; Tian Wang, Y.; Dong, Z. TRPV1 Activation Alleviates Cognitive and Synaptic Plasticity Impairments through Inhibiting AMPAR Endocytosis in APP23/PS45 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, C.; Cheng, X.; Wang, R.; Yan, X.; He, P.; Chen, H.; Yu, Z. A Breakdown in Microglial Metabolic Reprogramming Causes Internalization Dysfunction of α-Synuclein in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Cheng, J.; Kong, S.; Yang, X.; Jia, X.; Cheng, X.; Chen, L.; He, F.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Y.; et al. Inhibition of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) Mitigates Seizures. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 660–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Bai, L.; Lu, Z.; Gu, R.; Zhao, D.; Yan, F.; Bai, J. TRPV4 Contributes to ER Stress and Inflammation: Implications for Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekhar, P.; Poole, D.P.; Veldhuis, N.A. Role of Nonneuronal TRPV4 Signaling in Inflammatory Processes. In Advances in Pharmacology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 79, pp. 117–139. ISBN 9780128104132. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, W.; Ding, J.; Li, P.; Hu, L.; Shao, F. Inflammatory Caspases Are Innate Immune Receptors for Intracellular LPS. Nature 2014, 514, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathinam, V.A.K.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, F. Innate Immunity to Intracellular LPS. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.P.; Creagh, E.M. Caspase-4 and -5 Biology in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 919567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, B.; Yang, S.; Tang, X.; Wang, J.; Wei, D. The Protective Effects of Phoenixin-14 against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation and Inflammasome Activation in Astrocytes. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 69, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- From, A.H.; Fong, J.S.; Good, R.A. Polymyxin B Sulfate Modification of Bacterial Endotoxin: Effects on the Development of Endotoxin Shock in Dogs. Infect. Immun. 1979, 23, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, M.; Young, L.S. Protective Activity of Antibodies to Exotoxin A and Lipopolysaccharide at the Onset of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Septicemia in Man. J. Clin. Investig. 1979, 63, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Guo, S.; Deng, G. MicroRNA-106a Provides Negative Feedback Regulation in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation by Targeting TLR4. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 2308–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Kong, B.; Fang, J.; Qin, T.; Dai, C.; Shuai, W.; Huang, H. Ferrostatin-1 Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 9367–9376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M.; Gopinathan, G.; Salapatas, A.; Nares, S.; Gonzalez, M.; Diekwisch, T.G.H.; Luan, X. SETD1 and NF-ΚB Regulate Periodontal Inflammation through H3K4 Trimethylation. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Hong, H.-L.; Kim, G.M.; Leem, J.; Kwon, H.H. Protective Effects of Carnosic Acid on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Mice. Molecules 2021, 26, 7589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Vu, C.; Poloso, N.J. A Prostacyclin Analog, Cicaprost, Exhibits Potent Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Human Primary Immune Cells and a Uveitis Model. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 33, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, K.S.; Filor, V.; Bäumer, W. Early Inflammatory Events of Mastitis—a Pilot Study with the Isolated Perfused Bovine Udder. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, K.; Yang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, T.; Shaukat, A.; Yang, X.; Dai, A.; Wu, H.; Deng, G. MiR-148a Suppresses Inflammation in Lipopolysaccharide-induced Endometritis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ma, L.; Lin, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H. The Intervention Effect of Aspirin on a Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Preeclampsia-like Mouse Model by Inhibiting the Nuclear Factor-ΚB Pathway. Biol. Reprod. 2018, 99, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, R.; Tong, Y.; Chen, P.; Shen, Y.; Miao, S.; Liu, X. Neuroprotection by Dihydrotestosterone in LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 140, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kshirsagar, V.; Thingore, C.; Gursahani, M.; Gawali, N.; Juvekar, A. Hydrogen Sulfide Ameliorates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Memory Impairment in Mice by Reducing Apoptosis, Oxidative, and Inflammatory Effects. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 1310–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.M.; Lee, H.P.; Ham, Y.W.; Son, D.J.; Kim, H.Y.; Oh, K.W.; Han, S.-B.; Yun, J.; Hong, J.T. Piperlongumine Improves Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Amyloidogenesis by Suppressing NF-KappaB Pathway. Neuromol Med. 2018, 20, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qi, Y.; Li, Q.; Quan, H.; Liu, D.; Zhou, H. Connexin43 Inhibition Attenuated Dopaminergic Neuronal Loss in the Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Mice Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2022, 771, 136471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, A.; Rady, M.; Mahran, L.; Abou-Aisha, K. Pioglitazone Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Oxidative Stress, Dopaminergic Neuronal Loss and Neurobehavioral Impairment by Activating Nrf2/ARE/HO-1. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 2856–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, C.R.A.; Gomes, G.F.; Candelario-Jalil, E.; Fiebich, B.L.; de Oliveira, A.C.P. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation as a Bridge to Understand Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, I.; Corrigan, F.; Garg, S.; Zhou, X.-F.; Bobrovskaya, L. Further Characterization of Intrastriatal Lipopolysaccharide Model of Parkinson’s Disease in C57BL/6 Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronza, M.G.; Baldinotti, R.; Fetter, J.; Rosa, S.G.; Sacramento, M.; Nogueira, C.W.; Alves, D.; Praticò, D.; Savegnago, L. Beneficial Effects of QTC-4-MeOBnE in an LPS-Induced Mouse Model of Depression and Cognitive Impairments: The Role of Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability, NF-ΚB Signaling, and Microglial Activation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 99, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-L.; Tu, S.-C.; Hsu, M.-Y.; Chin, T.-Y. Diosgenin Prevents Microglial Activation and Protects Dopaminergic Neurons from Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neural Damage In Vitro and In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Muhammad, B.; Liu, X.; Quan, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; et al. IL-1β/IL-1R1 Signaling Induced by Intranasal Lipopolysaccharide Infusion Regulates Alpha-Synuclein Pathology in the Olfactory Bulb, Substantia Nigra and Striatum. Brain Pathol. 2020, 30, 1102–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossù, P.; Cutuli, D.; Palladino, I.; Caporali, P.; Angelucci, F.; Laricchiuta, D.; Gelfo, F.; De Bartolo, P.; Caltagirone, C.; Petrosini, L. A Single Intraperitoneal Injection of Endotoxin in Rats Induces Long-Lasting Modifications in Behavior and Brain Protein Levels of TNF-α and IL-18. J. Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tu, D.; Wilson, B.; Song, S.; Feng, J.; Hong, J.-S.; et al. A Novel Role of NLRP3-Generated IL-1β in the Acute-Chronic Transition of Peripheral Lipopolysaccharide-Elicited Neuroinflammation: Implications for Sepsis-Associated Neurodegeneration. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Caraveo, A.; Sayd, A.; Maus, S.R.; Caso, J.R.; Madrigal, J.L.M.; García-Bueno, B.; Leza, J.C. Lipopolysaccharide Enters the Rat Brain by a Lipoprotein-Mediated Transport Mechanism in Physioloical Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Luo, Z.; He, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption by Lipopolysaccharide and Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 768108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.A.; Gray, A.M.; Erickson, M.A.; Salameh, T.S.; Damodarasamy, M.; Sheibani, N.; Meabon, J.S.; Wing, E.E.; Morofuji, Y.; Cook, D.G.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption: Roles of Cyclooxygenase, Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Elements of the Neurovascular Unit. J. Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shoyaib, A.; Archie, S.R.; Karamyan, V.T. Intraperitoneal Route of Drug Administration: Should It Be Used in Experimental Animal Studies? Pharm. Res. 2019, 37, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, W.Y.W.; Bayna, E.; Molle, E.D.; Dalton, N.D.; Lai, N.C.; Bhargava, V.; Mendiola, V.; Clopton, P.; Tang, T. Recurrent Exposure to Subclinical Lipopolysaccharide Increases Mortality and Induces Cardiac Fibrosis in Mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Cui, Q.; Yang, W.; Guo, W. LPS Induces Dopamine Depletion and Iron Accumulation in Substantia Nigra in Rat Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 4942–4949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deng, I.; Bobrovskaya, L. Lipopolysaccharide Mouse Models for Parkinson’s Disease Research: A Critical Appraisal. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhapola, R.; Hota, S.S.; Sarma, P.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Medhi, B.; Reddy, D.H. Recent Advances in Molecular Pathways and Therapeutic Implications Targeting Neuroinflammation for Alzheimer’s Disease. Inflammopharmacol 2021, 29, 1669–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; He, X. Anti-Inflammatory Oleanolic Triterpenes from Chinese Acorns. Molecules 2016, 21, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y. A Combination of Indomethacin and Atorvastatin Ameliorates Cognitive and Pathological Deterioration in PrP-HAβPPswe/PS1ΔE9 Transgenic Mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 330, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkhah, A.; Saadi, M.; Pourabdolhossein, F.; Saleki, K.; Nouri, H.R. Indomethacin Attenuates Neuroinflammation and Memory Impairment in an STZ-Induced Model of Alzheimer’s like Disease. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2021, 43, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhillaj, E.; Morgese, M.G.; Tucci, P.; Furiano, A.; Luongo, L.; Bove, M.; Maione, S.; Cuomo, V.; Schiavone, S.; Trabace, L. Celecoxib Prevents Cognitive Impairment and Neuroinflammation in Soluble Amyloid β-Treated Rats. Neuroscience 2018, 372, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.R.B.; Firmino, M.; Jorge, J.S.; Ferreira, M.L.O.; Rodovalho, T.M.; Weis, S.N.; Souza, G.E.P.; Morais, P.C.; Sousa, M.V.; Souza, P.E.N.; et al. Increase of Reactive Oxygen Species in Different Tissues during Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Fever and Antipyresis: An Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Study. Free. Radic. Res. 2018, 52, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.Y.; Masocha, W. Indomethacin Augments Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Expression of Inflammatory Molecules in the Mouse Brain. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravleva, V.; Vaz-Silva, J.; Zhu, M.; Gomes, P.; Silva, J.M.; Sousa, N.; Sotiropoulos, I.; Waites, C.L. Rab35 and Glucocorticoids Regulate APP and BACE1 Trafficking to Modulate Aβ Production. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.-Q.; Cao, L.-L.; Liang, Y.-Y.; Wang, P. The Molecular Mechanism of Chronic High-Dose Corticosterone-Induced Aggravation of Cognitive Impairment in APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 13, 613421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.; Ortiz, A.; Castellino, J.; Kinney, J. Diabetes: Risk Factor and Translational Therapeutic Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, ejn.15619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Cui, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Shi, M.; Fan, H. Dexmedetomidine Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Hippocampal Neuronal Apoptosis via Inhibiting the P38 MAPK/c-Myc/CLIC4 Signaling Pathway in Rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 5533–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, C. Dexmedetomidine Provides Protection Against Hippocampal Neuron Apoptosis and Cognitive Impairment in Mice with Alzheimer’s Disease by Mediating the MiR-129/YAP1/JAG1 Axis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 5044–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałat, K.; Furgała-Wojas, A.; Sałat, R. The Microglial Activation Inhibitor Minocycline, Used Alone and in Combination with Duloxetine, Attenuates Pain Caused by Oxaliplatin in Mice. Molecules 2021, 26, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Boska, M.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Fox, H.S.; Xiong, H. Minocycline Attenuation of Rat Corpus Callosum Abnormality Mediated by Low-Dose Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Microglia Activation. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Luo, W. Memantine Ameliorates Oxaliplatin-Induced Neurotoxicity via Mitochondrial Protection. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 6688–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Fang, L.; Feng, D.; Tang, S.; Yue, S.; Huang, Y.; Han, J.; Lan, J.; Liu, W.; Gao, L.; et al. Memantine Ameliorates Pulmonary Inflammation in a Mice Model of COPD Induced by Cigarette Smoke Combined with LPS. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 2005–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, T.; Lu, L.; Yao, H.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, J. Novel and Potent Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease from Natural (±)-7,8-Dihydroxy-3-Methyl-Isochroman-4-One. Molecules 2022, 27, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Park, S.K.; Park, J.-H.; Jeong, H.-R.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Seol, E.; Hoe, H.-S. Donepezil Regulates LPS and Aβ-Stimulated Neuroinflammation through MAPK/NLRP3 Inflammasome/STAT3 Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, E.; Agrawal, R.; Nath, C.; Shukla, R. Effect of Anti-Dementia Drugs on LPS Induced Neuroinflammation in Mice. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 1977–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, G.; Taylor, K.I.; Anzures-Cabrera, J.; Marchesi, M.; Simuni, T.; Marek, K.; Postuma, R.B.; Pavese, N.; Stocchi, F.; Azulay, J.-P.; et al. Trial of Prasinezumab in Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhou, X.; Dong, X.; Lou, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, D. Preventive Effects of Arctigenin from Arctium Lappa L against LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Impairments in Mice. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022, 37, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.H.; Choi, G.S.; Monmai, C.; Rod-in, W.; Jang, A.; Park, W.J. Immunomodulatory Activities of Ammodytes Personatus Egg Lipid in RAW264.7 Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddi, K.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Tetali, S. Berberine, A Phytoalkaloid, Inhibits Inflammatory Response Induced by LPS through NF-Kappaβ Pathway: Possible Involvement of the IKKα. Molecules 2021, 26, 4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, F.; Yin, C.; Shi, J.; Gong, Q. Icariside II Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation through Inhibiting TLR4/MyD88/NF-ΚB Pathway in Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Zahoor, I.; Albarrati, A.; Albratty, M.; Meraya, A.M.; Najmi, A.; Bungau, S. Expatiating the Pharmacological and Nanotechnological Aspects of the Alkaloidal Drug Berberine: Current and Future Trends. Molecules 2022, 27, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweig, J.E.; Yao, H.; Coppola, K.; Jin, C.; Crawford, F.; Mullan, M.; Paris, D. Spleen Tyrosine Kinase (SYK) Blocks Autophagic Tau Degradation in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 13378–13395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.W.; Choe, K.; Park, J.S.; Lee, H.J.; Kang, M.H.; Ahmad, R.; Kim, M.O. Pharmacological Inhibition of Spleen Tyrosine Kinase Suppressed Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Dysfunction in LPS-Induced Neurodegeneration Model. Cells 2022, 11, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-E.; Leem, Y.-H.; Park, J.-S.; Kim, D.-Y.; Kang, J.L.; Kim, H.-S. Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Mechanisms of GTS-21, an α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonist, in Neuroinflammation and Parkinson’s Disease Mouse Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millot, P.; San, C.; Bennana, E.; Porte, B.; Vignal, N.; Hugon, J.; Paquet, C.; Hosten, B.; Mouton-Liger, F. STAT3 Inhibition Protects against Neuroinflammation and BACE1 Upregulation Induced by Systemic Inflammation. Immunol. Lett. 2020, 228, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, T.; Han, J.; Li, J.; Li, Z. Biological Evaluation of 7-O-Amide Hesperetin Derivatives as Multitarget-Directed Ligands for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. -Biol. Interact. 2021, 334, 109350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-J.; Wang, M.-R.; Dong, S.; Huang, L.-F.; He, Q.-R.; Gao, J.-M. 1,10-Seco-Eudesmane Sesquiterpenoids as a New Type of Anti-Neuroinflammatory Agents by Suppressing TLR4/NF-ΚB/MAPK Pathways. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 224, 113713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wang, S.; Gu, R.; Che, N.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.; Yuan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liao, Y. The XPO1 Inhibitor KPT-8602 Ameliorates Parkinson’s Disease by Inhibiting the NF-ΚB/NLRP3 Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 847605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Liang, D.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, Z. Gx-50 Reduces β-Amyloid-Induced TNF-α, IL-1β, NO, and PGE 2 Expression and Inhibits NF-ΚB Signaling in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016, 46, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Luan, M.-Z.; Yan, W.-B.; Zhao, F.-L.; Hou, Y.; Hou, G.-G.; Meng, Q.-G. Anti-Neuroinflammatory Effects of Novel 5,6-Dihydrobenzo[h]Quinazolin-2-Amine Derivatives in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated BV2 Microglial Cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 235, 114322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-A.; Hwang, K.; Kim, J.-E.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Yang, S.-J.; Cho, S.-W. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of N-Cyclooctyl-5-Methylthiazol-2-Amine Hydrobromide on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Response through Attenuation of NLRP3 Activation in Microglial Cells. BMB Rep. 2021, 54, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Woo, H.; Lee, H.-E.; Jeon, H.; Ryu, K.-Y.; han Nam, J.; Jeon, S.G.; Park, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Han, K.-M.; et al. The Novel DYRK1A Inhibitor KVN93 Regulates Cognitive Function, Amyloid-Beta Pathology, and Neuroinflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monga, S.; Weizman, A.; Gavish, M. The Efficacy of the Novel TSPO Ligands 2-Cl-MGV-1 and 2,4-Di-Cl-MGV-1 Compared to the Classical TSPO Ligand PK 11195 to Counteract the Release of Chemokines from LPS-Stimulated BV-2 Microglial Cells. Biology 2020, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.H.; Salama, M.; El-Fawal, H.A.N.; Abdelnaser, A. Selective GSK3β Inhibition Mediates an Nrf2-Independent Anti-Inflammatory Microglial Response. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 5591–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golderman, V.; Ben-Shimon, M.; Maggio, N.; Dori, A.; Gofrit, S.G.; Berkowitz, S.; Qassim, L.; Artan-Furman, A.; Zeimer, T.; Chapman, J.; et al. Factor VII, EPCR, APC Modulators: Novel Treatment for Neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ain, Q.U.; Batool, M.; Choi, S. TLR4-Targeting Therapeutics: Structural Basis and Computer-Aided Drug Discovery Approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Route and Period of LPS Administration | Dose | Species | Type of LPS | Performed Behavioral Tests | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intraperitoneal, 7 days | 500 and 750 μg/kg | mice | N/A | MWM, PAT, PT | [1] |

| intraperitoneal, 7 days | 250, 500 and 750 μg/kg | mice | E. coli O111:B4 | NOR, NAD, OFT | [14] |

| intraperitoneal, 5 days | 1 mg/kg | mice | E. coli O26:B6 * | MWM | [70] |

| intraperitoneal, 7 days | 250 μg/kg | mice | E. coli O55:B5 | MWM, Y-maze test | [71] |

| intraperitoneal, 7 days | 250 μg/kg | mice | E. coli O111:B4 | NOR, MWM | [23] |

| intraperitoneal, 7 days | 250 μg/kg | mice | E. coli O127:B8 | Y-maze test, NOR, ST, OFT | [77] |

| intraperitoneal, single dose | 5 mg/kg | mice | E. coli O26:B6 * | OFT, PT | [70] |

| intracebro- ventricular, single dose | 12 μg | mice | N/A | MWM, PAT, PT | [1] |

| intranigral, single dose | 5 μg | rats | E. coli O111:B4 | amphetamine- induced rotation test | [78] |

| intrastriatal, single dose | 10 µg | mice | N/A | rotarod test, buried food-seeking test, OFT | [76] |

| intranasal, 6 weeks | 10 µg | mice | E. coli O55:B5 | OFT, PT, olfactory function test | [79] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skrzypczak-Wiercioch, A.; Sałat, K. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Model of Neuroinflammation: Mechanisms of Action, Research Application and Future Directions for Its Use. Molecules 2022, 27, 5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175481

Skrzypczak-Wiercioch A, Sałat K. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Model of Neuroinflammation: Mechanisms of Action, Research Application and Future Directions for Its Use. Molecules. 2022; 27(17):5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175481

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkrzypczak-Wiercioch, Anna, and Kinga Sałat. 2022. "Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Model of Neuroinflammation: Mechanisms of Action, Research Application and Future Directions for Its Use" Molecules 27, no. 17: 5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175481

APA StyleSkrzypczak-Wiercioch, A., & Sałat, K. (2022). Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Model of Neuroinflammation: Mechanisms of Action, Research Application and Future Directions for Its Use. Molecules, 27(17), 5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175481