An Update of the Sanguinarine and Benzophenanthridine Alkaloids’ Biosynthesis and Their Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Biosynthesis of Sanguinarine and Related BZD: Physiological Roles and Applications

2.1. Synthesis and Regulation of Sanguinarine and Related Alkaloids

2.1.1. The Biosynthetic Pathway

2.1.2. Tissue Distribution and Regulation

2.2. Physiological Roles of Benzophenanthridines

2.2.1. Herbivore Deterrence of Benzophenanthridines

2.2.2. Antimicrobial Activity of Benzophenanthridines

2.3. Medical and Industrial Applications of Benzophenanthridines

3. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, A.; Menéndez-Perdomo, I.M.; Facchini, P.J. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in opium poppy: An update. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 1457–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Yin, J. Research progress on natural benzophenanthridine alkaloids and their pharmacological functions: A review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bisai, V.; Saina Shaheeda, M.K.; Gupta, A.; Bisai, A. Biosynthetic relationships and total syntheses of naturally occurring benzo [c] phenanthridine alkaloids. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2019, 8, 946–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Piña, J.; Vazquez-Flota, F. Pharmaceutical applications of the benzylisoquinoline alkaloids from Argemone mexicana L. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 2200–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielińska, S.; Jezierska-Domaradzka, A.; Wójciak-Kosior, M.; Sowa, I.; Junka, A.; Matkowski, A.M. Greater celandine’s ups and downs—21 centuries of medicinal uses of Chelidonium majus from the viewpoint of today’s pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liao, D.; Wang, P.; Jia, C.; Sun, P.; Qi, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, X. Identification and developmental expression profiling of putative alkaloid biosynthetic genes in Corydalis yanhusuo bulbs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; He, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Li, F.; Li, S.; Zhao, C.; Li, F. A Review of the traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and toxicology of Corydalis yanhusuo. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20957752. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, P.; Ma, Y.; Qing, Z.; Tang, Q.; Cao, H.; Cheng, P.; Zheng, Y.; Yuan, Z.; et al. The genome of medicinal plant Macleaya cordata provides new insights into benzylisoquinoline alkaloids metabolism. Mol. Plant. 2017, 5, 975–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rolland, A.; Fleurentin, J.; Lanhers, M.C.; Younos, C.; Misslin, R.; Mortier, F.; Pelt, J.M. Behavioural effects of the American traditional plant Eschscholzia californica: Sedative and anxiolytic properties. Planta Med. 1991, 57, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahlíková, L.; Opletal, L.; Kurfürst, M.; Macáková, K.; Kulhánková, A.; Hošt’álková, A. Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory compounds from Chelidonium majus (Papaveraceae). Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1934578X1000501110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Croaker, A.; King, G.J.; Pyne, J.H.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Liu, L. Sanguinaria canadensis: Traditional medicine, phytochemical composition, biological activities and current uses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samanani, N.; Facchini, P.J. Isolation and partial characterization of norcoclaurine synthase, the first committed step in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis, from opium poppy. Planta 2001, 213, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagel, J.M.; Facchini, P.J. Benzylisoquinoine alkaloid metabolism: A century of discovery and a brave new world. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 647–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liscombe, D.K.; MacLeod, B.P.; Loukanina, N.; Nandi, O.I.; Facchini, P.J. Evidence for the monophyletic evolution of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in angiosperms. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2501–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, D.; Konrad, B.; Toplak, M.; Lahham, M.; Messenlehner, J.; Winkler, J.; Macheroux, P. The family of berberine bridge enzyme-like enzymes: A treasure-trove of oxidative reactions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 632, 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, G.A.W.; Facchini, P.J. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in opium poppy. Planta 2014, 240, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díaz-Chávez, M.L.; Rolf, M.; Gesell, A.; Kutchan, T.M. Characterization of two methylenedioxy bridge-forming cytochrome P450-dependent enzymes of alkaloid formation in the Mexican prickly poppy Argemone mexicana. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 507, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.W.; Hudlicky, T. The Quest for a practical synthesis of morphine alkaloids and their derivatives by chemoenzymatic methods. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Hirakawa, H.; Hori, K.; Minakuchi, Y.; Toyoda, A.; Shitan, N.; Sato, F. Comparative analysis using the draft genome sequence of California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) for exploring the candidate genes involved in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2021, 85, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza-Muller, L.; Laines-Hidalgo, J.; Monforte-Gonzalez, M.; Vazquez-Flota, F. Alkaloid distribution in seeds of Argemone mexicana L. (Papaveraceae). J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2021, 65, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.; Baumert, A.; Vogel, M.; Roos, W. Sanguinarine reductase, a key enzyme of benzophenanthridine detoxification. Plant Cell Environ. 2006, 29, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alcantara, J.; Bird, D.A.; Franceschi, V.R.; Facchini, P.J. Sanguinarine biosynthesis is associated with the endoplasmic reticulum in cultured opium poppy cells after elicitor treatment. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, X.; Gao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Tu, P.; Chai, X. Alkaloids from the tribe Bocconieae (Papaveraceae): A chemical and biological review. Molecules 2014, 19, 13042–13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nwanyichukwu, P. Identification and Characterization of an Adenosine Triphosphate Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporter Ecabcb1 Involved in the Transport of Alkaloids in Eschscholzia californica. Master’s Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Loza-Muller, L.; Shitan, N.; Yamada, Y.; Vázquez-Flota, F. AmABCB1, an alkaloid transporter from seeds of Argemone mexicana L. (Papaveraceae). Planta 2021, 254, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Motomura, Y.; Sato, F. CjbHLH1 homologs regulate sanguinarine biosynthesis in Eschscholzia californica cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yamada, Y.; Shimada, T.; Motomura, Y.; Sato, F. Modulation of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis by heterologous expression of CjWRKY in Eschscholzia californica cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salmore, A.K.; Hunter, M.D. Elevational trends in defense chemistry, vegetation, and reproduction in Sanguinaria canadensis. J. Chem. Ecol. 2001, 27, 1713–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Jiang, W.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, L. Isoquinoline alkaloids from Macleaya cordata active against plant microbial pathogens. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 1934578X0900401120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, N.; Sharma, B. Toxicological effects of berberine and sanguinarine. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmeller, T.; Latz-Brüning, B.; Wink, M. Biochemical activities of berberine, palmatine and sanguinarine mediating chemical defense against microorganisms and herbivores. Phytochemistry 1997, 44, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, M.; Schmeller, T.; Latz-Bruning, B. Modes of action of allelochemical alkaloids: Interaction with neuroreceptors, DNA, and other molecular targets. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998, 24, 1881–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Wang, Y.; Zou, H.; Ding, N.; Geng, N.; Cao, C.; Zhang, G. Sanguinarine in Chelidonium majus induced antifeeding and larval lethality by suppressing food intake and digestive enzymes in Lymantria dispar. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 153, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, E.A.; Forister, M.L. Increased resistance to generalist herbivores in invasive populations of the California poppy (Eschscholzia californica). Divers. Distrib. 2005, 11, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.M.; Dodson, C.D.; Reichman, O.J. The roots of defense: Plant resistance and tolerance to belowground herbivory. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Tapia, M.; Sánchez-Soto, V.; Cámara Correia, K.; Pastirčáková, K.; Tovar-Pedraza, J.M. Powdery mildew of California poppy caused by Erysiphe eschscholziae in Mexico. Can. J. Plant. Pathol. 2018, 40, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Cho, S.E.; Piątek, M.; Shin, H.D. First report of powdery mildew caused by Erysiphe macleayae on Macleaya microcarpa in Poland. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huang, P.; Yu, L.; Zeng, J. First report of root rot caused by Fusarium oxysporum on Macleaya cordata in China. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, N.R.; Jennings, J.C.; Bailey, B.A.; Farr, D.F. Dendryphion penicillatum and Pleospora papaveracea, destructive seedborne pathogens and potential mycoherbicides for Papaver somniferum. Phytopathology 2000, 90, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, X.J.; Miao, F.; Yao, Y.; Cao, F.J.; Yang, R.; Ma, Y.N.; Qin, B.-F.; Zhou, L. In vitro antifungal activity of sanguinarine and chelerythrine derivatives against phytopathogenic fungi. Molecules 2012, 17, 13026–13035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Gao, Z.F.; Zhao, J.Y.; Li, W.B.; Zhou, L.; Miao, F. New class of 2-Aryl-6-chloro-3, 4-dihydroisoquinolinium salts as potential antifungal agents for plant protection: Synthesis, bioactivity and structure–activity relationships. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1906–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagel, J.M.; Morris, J.S.; Lee, E.J.; Desgagné-Penix, I.; Bross, C.D.; Chang, L.; Chen, X.; Farrow, S.C.; Zhang, Y.; Soh, J.; et al. Transcriptome analysis of 20 taxonomically related benzylisoquinoline alkaloid-producing plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trujillo-Villanueva, K.; Rubio-Piña, J.; Monforte-González, M.; Vázquez-Flota, F. Fusarium oxysporum homogenates and jasmonate induce limited sanguinarine accumulation in Argemone mexicana cell cultures. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 32, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guízar-González, C.; Monforte-González, M.; Vázquez-Flota, F. Yeast extract induction of sanguinarine biosynthesis is partially dependent on the octadecanoic acid pathway in cell cultures of Argemone mexicana L., the Mexican poppy. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Färber, K.; Schumann, B.; Miersch, O.; Roos, W. Selective desensitization of jasmonate-and pH-dependent signaling in the induction of benzophenanthridine biosynthesis in cells of Eschscholzia californica. Phytochemistry 2003, 6, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, W.; Viehweger, K.; Dordschbal, B.; Schumann, B.; Evers, S.; Steighardt, J.; Schwartze, W. Intracellular pH signals in the induction of secondary pathways—The case of Eschscholzia californica. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 163, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.M.; Shang, X.F.; Lawoe, R.K.; Liu, Y.Q.; Zhou, R.; Sun, Y.F.; Li, J.; Yang, G.Z.; Yang, C.J. Anti-phytopathogenic activity and the possible mechanisms of action of isoquinoline alkaloid sanguinarine. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 159, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjago, W.M.; Zeng, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Biregeya, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Peng, M.; Yan, C.; Mingyue, S.; et al. The molecular mechanism underlying pathogenicity inhibition by sanguinarine in Magnaporthe oryzae. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4669–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuria, T.K.; Santra, M.K.; Panda, D. Sanguinarine blocks cytokinesis in bacteria by inhibiting FtsZ assembly and bundling. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 6584–16593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingorance, J.; Rivas, G.; Vélez, M.; Gómez-Puertas, P.; Vicente, M. Strong FtsZ is with the force: Mechanisms to constrict bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 18, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Lebas, B.; Liefting, L.; Veerakone, S.; Wei, T.; Ward, L. Opium poppy mosaic virus, a new umbravirus isolated from Papaver somniferum in New Zealand. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasa, M.; Šoltys, K.; Predajňa, L.; Sihelská, N.; Nováková, S.; Šubr, Z.; Kraic, J.; Mihálik, D. Molecular and biological characterization of turnip mosaic virus isolates infecting poppy (Papaver somniferum and P. rhoeas) in Slovakia. Viruses 2018, 10, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

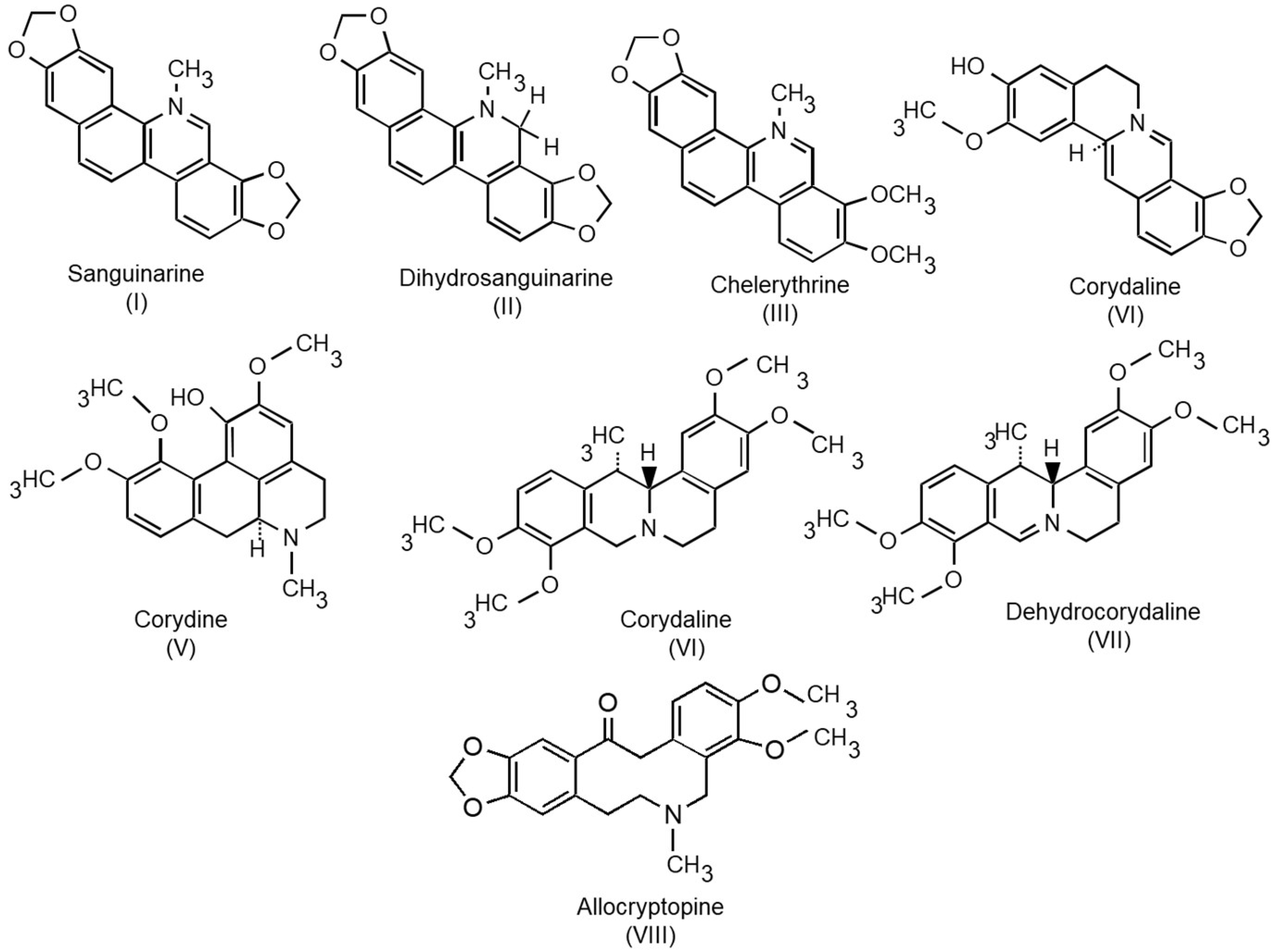

- Dong, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhong, X.; Ou, X.; Yun, X.; Wang, M.; Ren, S.; Quing, Z.; Zeng, J. Identification of the impurities in Bopu Powder® and Sangrovit® by LC-MS combined with a screening method. Molecules 2021, 26, 3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, T.; Qian, W. In vitro anti-biofilm efficacy of sanguinarine against carbapenem-resistant Serratia marcescens. Biofouling 2021, 37, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Lyu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, N.; Wen, Z.; Chen, S. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of sanguinarine against Providencia rettgeri in vitro. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Guan, G.; Wang, H. The anticancer effect of sanguinarine: A review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 2760–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galadari, S.; Rahman, A.; Pallichankandy, S.; Thayyullathil, F. Molecular targets and anticancer potential of sanguinarine—A benzophenanthridine alkaloid. Phytomedicine 2017, 34, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.Q.; Rashid, K.; AlAmodi, A.A.; Agha, M.V.; Akhtar, S.; Hakeem, I.; Raza, S.S.; Uddin, S. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cancer pathogenesis and therapy: An update on the role of ROS in anticancer action of benzophenanthridine alkaloids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Achkar, I.W.; Siveen, K.S.; Kuttikrishnan, S.; Prabhu, K.S.; Khan, A.Q.; Eiman, I.A.; Fairooz, S.; Jerobin, J.; Raza, A.; et al. Sanguinarine induces apoptosis pathway in multiple myeloma cell lines via inhibition of the JaK2/STAT3 signaling. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perillo, B.; di Donato, M.; Pezone, A.; di Zazzo, E.; Giovannelli, P.; Galasso, G.; Castoira, G.; Migliaccio, A. ROS in cancer therapy: The bright side of the moon. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Shang, J.; Xia, W. Targets and candidate agents for type 2 diabetes treatment with computational bioinformatics approach. J. Diabetes Res. 2014, 763936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, J. Sanguinarine ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in rats through nuclear factor-Kappa B and nuclear-factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/hemeoxygenase-1 pathways. Curr. Top. Nutraceutical Res. 2020, 19, 398–404. [Google Scholar]

- Falchi, F.A.; Borlotti, G.; Ferretti, F.; Pellegrino, G.; Raneri, M.; Schiavoni, M.; Caselli, A.; Briani, F. Sanguinarine inhibits the 2-ketoguconate pathway of glucose utilization in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 744458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.C.; Chang, F.R.; Khalil, A.T.; Hsieh, P.W.; Wu, Y.C. Cytotoxic benzophenanthridine and benzylisoquinoline alkaloids from Argemone mexicana. Z. Für Nat. C 2003, 58, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hazra, S.; Kumar, G.S. Structural and thermodynamic studies on the interaction of iminium and alkanolamine forms of sanguinarine with hemoglobin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 3771–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P.; Kumar, G.S. Sanguinarine and its role in Chronic diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 928, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Mao, K.; Gu, Q.; Wu, W. The antiangiogenic effect of sanguinarine chloride on experimental chloroidal neovascularization in mice via inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 15, 638215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Choi, W.Y.; Hong, S.H.; Kim, S.O.; Kim, G.Y.; Lee, W.H.; Yoo, Y.H. Anti-invasive activity of sanguinarine through modulation of tight junctions and matrix metalloproteinase activities in MDA-MB-231 human breast carcinoma cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009, 179, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.Y.; Jin, C.Y.; Han, M.H.; Kim, G.Y.; Kim, N.D.; Lee, W.H.; Kim, S.K.; Choi, Y.H. Sanguinarine sensitizes human gastric adenocarcinoma AGS cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis via down-regulation of AKT and activation of caspase-3. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 4457–4465. [Google Scholar]

- Achkar, I.W.; Mraiche, F.; Mohammed, R.M.; Uddin, S. anticancer potential of sanguinarine for various human malignancies. Future Med. Chem. 2017, 9, 933–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Fan, T.; Li, W.; Xing, W.; Huang, H. The anti-inflammatory effects of sanguinarine and its modulation of inflammatory mediators from peritoneal macrophages. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 689, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackraj, I.; Govender, T.; Gathiram, P. Sanguinarine. Cardiovasc. Drugs Rev. 2008, 26, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, M.; Zarghi, A.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A.; Irannejad, H. Therapeutic potential of chelerythrine as a multi-purpose adjuvant for the treatment of COVID-19. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 2321–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, M.; Fan, P.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, H. Chelerythrine chloride induces apoptosis in renal cancer HEK-293 and SW-839 cell lines. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 3917–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wangchuk, P.; Sastraruji, T.; Taweechotipatr, M.; Keller, P.; Pyne, S. Anti-inflammatory, Anti-bacterial and anti-acetylcholinesterase activities of two isoquinoline alkaloids-scoulerine and cheilanthifoline. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1801–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, N.; Wang, P.; Wang, P.; Ma, C.; Kang, W. Antibacterial mechanism of chelerythrine isolated from root of Toddalia asiatica (Linn) Lam. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vázquez-Flota, F.A.; Loyola-Vargas, V.M. In vitro plant cell culture as the basis for the development of a Research Institute in México: Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2003, 39, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xool-Tamayo, J.; Tamayo-Ordoñez, Y.; Monforte-González, M.; Muñoz-Sánchez, J.A.; Vázquez-Flota, F. Alkaloid biosynthesis in the early stages of the germination of Argemone mexicana L. (Papaveraceae). Plants 2021, 10, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, P.; Khan, S.A.; Mathur, A.K.; Ghosh, S.; Shanker, K.; Kalra, A. Improved sanguinarine production via biotic and abiotic elicitations and precursor feeding in cell suspensions of latex-less variety of Papaver somniferum with their gene expression studies and upscaling in bioreactor. Protoplasma 2014, 251, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemura, T.; Ikezawa, N.; Iwasa, K.; Sato, F. Molecular cloning and characterization of a cytochrome P450 in sanguinarine biosynthesis from Eschscholzia californica cells. Phytochemistry 2013, 91, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Xie, H.; Reiser, O.; Zeng, J.; Cheng, P. Visible-light-promoted biomimetic reductive functionalization of quaternary benzophenanthridine alkaloids. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2390–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindan, N.; Jeganmohan, M. A short total synthesis of benzophenanthridine alkaloids via a rhodium (III)-catalyzed C−H ring-opening reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 14826–14843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croaker, A.; Kinga, G.J.; Pyned, J.H.; Anoopkumar-Dukiec, S.; Simanekf, V.; Liua, L. Carcinogenic potential of sanguinarine. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2017, 774, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, M.E.; Mahmoud, N.; Sugimoto, Y.; Efferth, T.; Abdel-Aziz, H. Molecular determinants of sensitivity or resistance of cancer cells toward sanguinarine. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossati, E.; Ekins, A.; Narcross, L.; Zhu, Y.; Falgueyret, J.P.; Beaudoin, G.A.; Facchini, P.J.; Martin, V.J. Reconstitution of a 10-gene pathway for synthesis of the plant alkaloid dihydrosanguinarine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Plant Species | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|

| Argemone mexicana L. (Papaveraceae) | Antiprotozoals: to dissolve eye cataracts, to remove warts, and to treat skin infections | [4] |

| Chelidonium majus L. (Papaveraceae) | Skin, liver, and eye diseases; antiparasitic | [5] |

| Corydalis yanhusuo Chou (Papaveraceae) | Analgesic for chest pain, post-partum blood stasis, and spleen and stomach stasis | [6,7] |

| Macleaya cordata Willd (Papaveraceae) | Anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities | [8] |

| Eschscholzia californica Cham (Papaveraceae) | Sedative, anxiolytic, analgesic, soporific, spasmolytic, diuretic, and diaphoretic | [9,10] |

| Sanguinaria canadensis L. (Papaveraceae) | To treat cold and congestion, sore throats, emetic, abdominal cramps, lumps, wound infections, and rheumatism | [11] |

| Enzyme and EC Number | Function | Subcellular Localization | Organisms amd Acc. Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| l-Tyrosine decarboxylase (TyDC) EC 4.1.1.25 | Decarboxylates of l-tyrosine to produce tyramine | Cytosol | P. somniferum (P54768) Thalictrum flavum (Q9AXN7) A. mexicana (D2SMM8) |

| s-Norcoclaurine synthase (NCS) EC 4.2.1.78 | Condenses dopamine and 4-HPDA, producing s-norcoclaurine | Endoplasmic reticulum lumen and vacuole | P. somniferum (Q4QTJ2) T. flavum (Q67A25) A. mexicana (EU881891) |

| s-Norcoclaurine-6-O-methyltransferase (6OMT) EC 2.1.1.128 | Transfers a methyl group from SAM to s-norcoclaurine, forming coclaurine, and to r,s-norcoclaurine, formimg r-norprotosinomenine, s-norprotosinomenine, and (r,s)-isoorientaline | Membrane integral protein | P. somniferum (Q6WUC1) Coptis japonica (Q9LEL6) |

| Reticuline oxidase: berberine bridge enzyme (BBE) EC:1.21.3.3 | Converts s-reticuline in s-scoulerine by forming of a carbon–carbon bond (C8) between the N-methyl group and the phenolic ring | Cytoplasmic vesicles | P. somniferum (P93479) E. californica (P30986) A. mexicana (D2SMM9) |

| Cheilanthifoline synthase (CheSyn) EC:1.14.19.65 | Converts s-scoulerine into r,s-cheilanthifoline by forming a methylenedioxy brigde | Endoplasmic reticulum membrane | E. californica (B5UAQ8) A. mexicana (CYP719A14) |

| Stylopine synthase (StySyn) EC:1.14.19.73 | Forms a methylenedioxy bridge on ring A (2,3 position), transforming s-cheilanthifoline to s-stylopine, s-scoulerine to s-nandinine, and s-tetrahydrocolumbamine to s-canadine | Smooth endoplasmic reticulum membrane | E. californica (Q50LH4) A. mexicana (B1NF19) |

| s-Tetrahydroprotoberberine N-methyltransferase TNMT EC:2.1.1.122 | Converts stylopine, canadine, and tetrahydropalmatine to their corresponding N-methylated products | Cytosol | P. somniferum (Q108P1) E. californica C3SBS8 |

| Methyltetrahydroprotoberberine 14-monooxygenase (MSH) EC:1.14.14.97 | Transforms, by oxidation, N-methylstylopine and N-methylcanadine into protopine and allocryptopine, respectively | Membranal protein | P. somniferum (L7X3S1) |

| Protopine 6-hydroxylase (P6H) EC:1.14.14.98 | Converts protopine and allocryptopine to dihydrosanguinarine and dihydrochelerythrine by hydroxylation at position 6 | Endoplasmic reticulum membrane | E. californica (F2Z9C1) P. somniferum (L7X0L7) |

| Dihydrobenzophenanthridine oxidase (DBOX) EC 1.5.3.12 | Catalyzes a two-electron oxidation of dihydrosanguinarine, forming sanguinarine | Endoplasmic reticulum | P. somniferum (AAC61839) |

| Sanguinarine reductase (SanR) EC:1.3.1.107 | Catalyzes reduction of benzophenanthridines, preferentially sanguinarine, to the dihydroalkaloids; involved in detoxifying the phytoalexins produced by plant itself | Vacoule | E. californica (D5JWB3) |

| Alkaloid | Effects | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sanguinarine (I) | Antimicrobial | Halts formation of contracting belt by binding to the FtsZ protein | [50,63] |

| Interferes with carbohydrate metabolisms by inhibiting glucose transport and the 2-ketogluconate pathway | |||

| Increases sensitivity to β-lactam antibiotics | |||

| Antiretroviral | Inhibits transcriptase reverse | [64] | |

| Anticancer | Cytotoxic Intercalates DNA and RNA, affecting topoisomerase action and cell division Arrests cell cycle at S and G1 phases by interfering with cyclins and CDK Activates and modulates ROS depending on apoptotic pathways through effects on p53, Bcl-2, caspases, IAP, and autophagy affecting MAPK and ERK Tumor development and metastasis Restrains neovascularization by downregulating expression of the endothelial growth factor Reinforces cell-tight junction Chemosensitization Potentiates cytotoxicity of different agents | [30,59,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] | |

| Anti-inflammatory | Reduces the release of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α; IL-1β; and IL-6 | [71,72] | |

| Chelerythrine (III) | Adjuvant in COVID-19 treatment Anti-inflammatory | Prevents hyper-inflammatory immune response regulating signaling pathways mediated by Nrf2, NF-κB, and p38 MAPK | [73,74] |

| Reduces protein kinase C-α/-β inhibitory activity, preventing cerebral vasospasm, eryptosis, and pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis | |||

| Antiviral | Viral RNA-intercalation | [73] | |

| Anticancer | Reduces phosphorylation of ERK and Akt, downplaying the activation of p53, B-cell Bcl-2, caspases, and PARP | [74] | |

| Cheilanthifoline (IV) | Anti-inflammatory | Reduces the release of proinflammatory cytokines and anti-AChE | [75] |

| Antimicrobial | Hinders expression of MRSA genes and disrupts membrane integrity | [76] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laines-Hidalgo, J.I.; Muñoz-Sánchez, J.A.; Loza-Müller, L.; Vázquez-Flota, F. An Update of the Sanguinarine and Benzophenanthridine Alkaloids’ Biosynthesis and Their Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27041378

Laines-Hidalgo JI, Muñoz-Sánchez JA, Loza-Müller L, Vázquez-Flota F. An Update of the Sanguinarine and Benzophenanthridine Alkaloids’ Biosynthesis and Their Applications. Molecules. 2022; 27(4):1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27041378

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaines-Hidalgo, José Ignacio, José Armando Muñoz-Sánchez, Lloyd Loza-Müller, and Felipe Vázquez-Flota. 2022. "An Update of the Sanguinarine and Benzophenanthridine Alkaloids’ Biosynthesis and Their Applications" Molecules 27, no. 4: 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27041378

APA StyleLaines-Hidalgo, J. I., Muñoz-Sánchez, J. A., Loza-Müller, L., & Vázquez-Flota, F. (2022). An Update of the Sanguinarine and Benzophenanthridine Alkaloids’ Biosynthesis and Their Applications. Molecules, 27(4), 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27041378