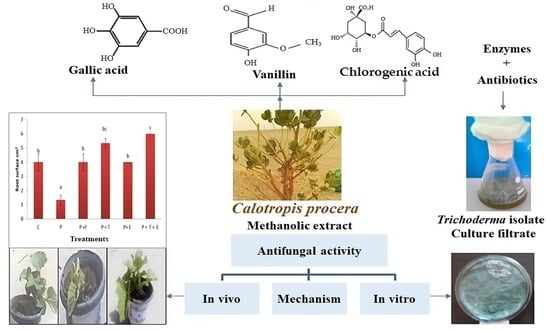

Polyphenols-Rich Extract of Calotropis procera Alone and in Combination with Trichoderma Culture Filtrate for Biocontrol of Cantaloupe Wilt and Root Rot Fungi

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. In Vitro Experiments

2.1.1. Screening for Antagonistic Potential of Trichoderma Isolates against Tested Phytopathogenic Fungi (Dual-Culture Experiments)

2.1.2. Analysis of the Enzymatic Crude Extract and Antibiotics in Fungal Filtrate of the Most Active Trichoderma Isolate

2.1.3. Effect of Trichoderma spp. (T2) on Tested Phytopathogenic Fungi under Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.1.4. Screening of Plant Extracts as Antifungal Activities against Tested Fungi

2.1.5. Effect of Different Concentrations of Calotropis procera against Tested Fungi

2.2. Phytochemical Analysis of Most Active Plant Extract

2.3. In Vivo Experiments

2.3.1. Effect of Trichoderma spp. filtrate and Methanol Extract of C. procera Each or in Combination on Cantaloupe Plants Infected with F. oxysporum

Disease Incidence

2.3.2. Growth Parameters

2.3.3. Root Surface Area

2.3.4. Pearson Correlation Analysis

2.3.5. Total Phenol Content

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Isolation, Purification, and Identification of F. oxysporum, P. ultimum, and R. solani

3.2. Isolation and Identification of Trichoderma spp.

3.3. Collection of Wild Plants, Identification, and Extractions

3.4. Disease Control (In Vitro Experiments)

3.4.1. The Inhibitory Activity of Trichoderma spp. Isolates versus Tested Phytopathogenic Fungi (Dual-Culture Experiments)

3.4.2. Enzymes Assays and Antibiotics of Selected Trichoderma spp. Isolate in Culture Filtrate

Enzymes Assays

3.5. Sample Preparation for Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.6. Antifungal Screening of Selected Plant Extracts

3.7. In Vitro Evaluation of the Effect Different Concentrations of C. procera against Tested Fungi

3.8. Phytochemical Analysis of Most Active Plant Extract by HPLC UV–Vis Detectors

3.9. Disease Control (In Vivo Experiments)

Effects of Trichoderma spp. filtrate and C. procera plant extract on cantaloupe plants infected by F. oxysporum

3.10. Measurements of the Growth Parameters of the Cantaloupe Plants

3.11. Total Phenol Estamations

3.12. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Yavuz, D.; Seymen, M.; Yavuz, N.; Çoklar, H.; Ercan, M. Effects of water stress applied at various phenological stages on yield, quality, and water use efficiency of melon. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 246, 106673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saied, A.A. Markets, Marketing and Exporting Chances of Cantaloupe: Producing Melon (Cantaloupe) For Exporting; Agricultural Technology Utilization and Transfer Project (ATUT): Roma, Italy, 1998; pp. 10–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tabassum, S.; Ossola, A.; Marchin, R.; Ellsworth, D.S.; Leishman, M. Assessing the relationship between trait-based and horticultural classifications of plant responses to drought. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, T.; Rincón, A.M.; Limón, M.C.; Codon, A.C. Biocontrol mechanisms of Trichoderma strains. Int. Microbiol. 2004, 7, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manczinger, L.; Antal, Z.; Kredics, L. Ecophysiology and breeding of Mycoparasitic Trichoderma strains. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2002, 49, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, M.S.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Al-Askar, A.A.; Arishi, A.A.; Abdelhakim, A.M.; Hashem, A.H. Plant growth-promoting fungi as biocontrol tool against Fusarium wilt disease of tomato plant. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Aparicio, F.; Lisón, P.; Rodrigo, I.; Bellés, J.M.; López-Gresa, M.P. Signaling in the tomato immunity against Fusarium oxysporum. Molecules 2021, 26, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, V.; Ramesh, R.; Saravanan, K.; Deep, S.; Sharma, M. Biocontrol genes from Trichoderma species: A review. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 19898–19907. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo-Prieto, S.; Campelo, M.P.; Lorenzana, A.; Rodríguez-González, A.; Reinoso, B.; Gutiérrez, S. Antifungal activity and bean growth promotion of Trichoderma strains isolated from seed vs soil. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 158, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E.; Kubicek, C.P. (Eds.) Trichoderma and Gliocladium, Volume 2: Enzymes, Biological Control and Commercial Applications, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Iannaccone, F.; Alborino, V.; Dini, I.; Balestrieri, A.; Marra, R.; Davino, R.; Di Francia, A.; Masucci, F.; Serrapica, F.; Vinale, F. In Vitro Application of Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzymes from Trichoderma spp. to Improve Feed Utilization by Ruminants. Agriculture 2022, 12, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçük, Ç.; Kivanç, M. In vitro antifungal activity of strains of Trichoderma Harzianum. Turk. J. Biol. 2004, 28, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, B.R. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: Mechanisms and applications. Scientifica 2012, 15, 963401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isman, M.B. Botanical insecticides, deterrents, and repellents in modern agriculture and an increasingly regulated world. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acheuk, F.; Basiouni, S.; Shehata, A.A.; Dick, K.; Hajri, H.; Lasram, S.; Yilmaz, M.; Emekci, M.; Tsiamis, G.; Spona-Friedl, M. Status and Prospects of Botanical Biopesticides in Europe and Mediterranean Countries. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemimi, A.; Lakhssassi, N.; Baharlouei, A.; Watson, D.G.; Lightfoot, D.A. Phytochemicals: Extraction, Isolation, and Identification of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Extracts. Plants 2017, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, L.M.; Galal, T.M.; Farahat, E.A.; El-Midany, M.M. The biology of Calotropis procera (Aiton) WT. Trees 2015, 29, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, M.M.; Farah, M.; Abou-Tarboush, F.; Al-Anazi, K.; Al-Harbi, N.; Ali, M.; Hailan, W.Q. Anticancer effects of Calotropis procera latex extract in mcf-7 breast cancer cells. Phcog. Mag. 2020, 16, 550–556. [Google Scholar]

- Falana, M.B.; Nurudeen, Q.O. Evaluation of phytochemical constituents and in vitro antimicrobial activities of leaves extracts of Calotropis procera against certain human pathogens. Not. Sci. Biol. 2020, 12, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E.; Petzoldt, R.; Comis, A.; Chen, J. Interactions between Trichoderma harzianum strain T22 and maize inbred line Mo17 and effects of these interactions on diseases caused by Pythium ultimum and Colletotrichum graminicola. J. Phytopathol. 2004, 94, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, F.G.; Reynoso, M.M.; Sofia, M.F.; Torres, A.M. Biological control by Trichoderma species of Fusarium solani causing peanut brown root rot under field conditions. J. Crop Prot. 2007, 26, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad, Y. Biological Control of Foliar Pathogens by Means of Trichoderma harzianum and Potential Modes of Action. J. Crop Prot. 2000, 19, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, R.C. Mechanisms employed by Trichoderma species in the biological control of plant diseases, the history and evolution of current concepts. J. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Oh, Y.T.; Lee, D.Y.; Cho, E.; Hwang, B.S.; Jeon, J. Large-Scale Screening of the Plant Extracts for Antifungal Activity against the Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Plant Pathol. J. 2022, 38, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualhato, T.F.; Lopes, F.A.C.; Steindorff, A.S.; Brandao, R.S.; Jesuino, R.S.A.; Ulhoa, C.J. Mycoparasitism studies of Trichoderma species against three phytopathogenic fungi: Evaluation of antagonism and hydrolytic enzyme production. Biotechnol. Lett. 2013, 35, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elad, Y.; Chet, I.; Henis, Y. Degradation of plant pathogenic fungi by Trichoderma harzianum. Can. J. Microbiol. 1982, 28, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbar, J.; Abransky, D.; Cohen, D.; Chet, I. Plant growth enhancement and disease control by Trichoderma harzianum in vegetable seedlings grown under commercial conditions. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1994, 100, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E. Overview of Mechanisms and Uses of Trichoderma spp. J. Phytopathol. 2006, 96, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunbury-Blanchette, A.L.; Walker, A.K. Trichoderma species show biocontrol potential in dual culture and greenhouse bioassays against Fusarium basal rot of onion. Biol. Control 2019, 130, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, L.; Din, I.U.; Arafat, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Antagonistic activity of Trichoderma spp. against Fusarium oxysporum in rhizosphere of radix pseudostellariae triggers the expression of host defense genes and improves its growth under long-term monoculture system. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 579920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Horwitz, B.A.; Zachow, C.; Berg, G.; Zeilinger, S. Trichoderma-plant-pathogen interactions: Advances in genetics of biological control. Indian J. Microbiol. 2012, 53, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, M.M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, E.A.; Gala, A.; Rashwan, O. Caffeoyl derivatives from the seeds of Ipomoea fistulosa. Int. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 33, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, P.S.; Malik, N.G.; Chavan, P.D. Allelopathic effects of Ipomoea carnea subsp. fistulosa on growth of wheat rice sorghum and kidneybean. Allelopath. J. 1997, 4, 345–348. [Google Scholar]

- El Khetabi, A.; Lahlali, R.; Ezrari, S.; Radouane, N.; Lyousfi, N.; Banani, H.; Askarne, L.; Tahiri, A.; El Ghadraoui, L.; Belmalha, S.; et al. Role of Plant Extracts and Essential Oils in Fighting against Postharvest Fruit Pathogens and Extending Fruit Shelf Life: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 120, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palou, L.; Ali, A.; Fallik, E.; Romanazzi, G. GRAS, Plant and Animal-Derived Compounds as Alternatives to Conventional Fungicides for the control of Postharvest Diseases of Fresh Horticultural Produce. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 122, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Martínez, F.J.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Encinar, J.A.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.C.; Micol, V. Antimicrobial Capacity of Plant Polyphenols against Gram-Positive Bacteria: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 2576–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattnaik, P.K.; Kar, D.; Chhatoi, H.; Shahbazi, S.; Ghosh, G.; Kuanar, A. Chemometric profile & antimicrobial activities of leaf extract of Calotropis procera and Calotropis gigantea. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- El-Nagar, A.; Elzaawely, A.A.; Taha, N.A.; Nehela, Y. The antifungal activity of gallic acid and its derivatives against Alternaria solani, the causal agent of tomato early blight. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, W.S.; Lee, D.G. Antifungal action of chlorogenic acid against pathogenic fungi, mediated by membrane disruption. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 82, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, M.; Takada, K. Multiple effects of green tea catechin on the antifungal activity of antimycotics against Candida albicans. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 53, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Lee, H.S.; Oh, H.S.; Kim, H.T.; Lee, Y.H. Antifungal activity and mode of action of Galla rhois-derived phenolics against Phytopathogenic fungi. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2005, 81, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.P.; Atong, M.; Rossall, S. The role of syringic acid in the interaction between oil palm and Ganoderma boninense, the causal agent of basal stem rot. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.N.; Saha, A. Accumulation of antifungal compounds in tea leaf tissue infected with Bipolaris carbonum. Folia Microbiol. 1994, 39, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanzada, B.; Akhtar, N.; Okla, M.K.; Alamri, S.A.; Al-Hashimi, A.; Baig, M.W.; Mirza, B. Profiling of antifungal activities and in silico studies of natural polyphenols from some plants. Molecules 2021, 26, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Junior, I.F.; Raimondi, M.; Zacchino, S.; Cechinel Filho, V.; Noldin, V.F.; Rao, V.S.; Martins, D.T. Evaluation of the antifungal activity and mode of action of Lafoensia pacari A. St.-Hil., Lythraceae, stem-bark extracts, fractions and ellagic acid. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2010, 20, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; Mendoza, L.; Cotoras, M. Alteration of oxidative phosphorylation as a possible mechanism of the antifungal action of p-coumaric acid against Botrytis cinerea. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Cortes, T.; Pérez España, V.H.; López Pérez, P.A.; Rodríguez-Jimenes, G.D.C.; Robles-Olvera, V.J.; Aparicio Burgos, J.E.; Cuervo-Parra, J.A. Antifungal activity of vanilla juice and vanillin against Alternaria alternata. CyTA-J. Food 2019, 17, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Meng, X.; Lin, X.; Duan, N.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S. Antifungal activity and inhibitory mechanisms of ferulic acid against the growth of Fusarium graminearum. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, J.R.; Sgariglia, M.A.; Torrez, J.A.C.; Aguilar, F.A.; Pero, E.J.; Sampietro, D.A.; Labadie, G.R. Antifungal activity and toxicity studies of flavanones isolated from Tessaria dodoneifolia aerial parts. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swari, D.A.M.A.; Santika, I.W.M.; Aman, I.G.M. Antifungal activities of ethanol extract of rosemary leaf (Rosemarinus officinalis L.) against Candida albicans. J. Pharm. Sci. Appl. 2020, 2, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, I.; Ozcelik, B.; Kartal, M.; Aslan, S.; Sener, B.; Ozguven, M. Quantification of daidzein, genistein and fatty acids in soybeans and soy sprouts, and some bioactivity studies. Acta Biol. Cracov. 2007, 49, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tempesti, T.C.; Alvarez, M.G.; de Araújo, M.F.; Catunda Júnior, F.E.A.; de Carvalho, M.G.; Durantini, E.N. Antifungal activity of a novel quercetin derivative bearing a trifluoromethyl group on Candida albicans. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 2217–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogno, F.; Mascoti, L.; Sanchez, C.; Garibotto, F.; Giannini, F.; Kurina-Sanz, M.; Enriz, R. Structure-antifungal activity relationship of cinnamic acid derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10635–10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilk, S.; Saglam, N.; Özgen, M. Kaempferol loaded lecithin/chitosan nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization, and their potential applications as a sustainable antifungal agent. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin, M.T.; Mostafa, A.A.F.; Al-Askar, A.A. In vitro antagonistic activity of Trichoderma spp. against fungal pathogens causing black point disease of wheat. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2022, 16, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, M.T.; Van Nguyen, M.; Han, J.W.; Park, M.S.; Kim, H.; Choi, G.J. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of sorbicillinoids produced by Trichoderma longibrachiatum. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinu, K.; Sati, P.; Pandey, A. Trichoderma gamsii (NFCCI 2177): A newly isolated endophytic, psychrotolerant, plant growth promoting, and antagonistic fungal strain. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013, 54, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, D.; Barari, H. Effect of subtilin (Bacillus subtilis) against tomato wilts disease. Sonboleh 2008, 175, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Zeid, N.M.; Arafa, M.K.; Attia, S. Biological control of pre- and postemergence diseases on faba bean, lentil and chickpea in Egypt. Egypt J. Agric. Res. 2003, 81, 1491–1503. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, G.; Dawar, S.; Sattar, A.; Dawar, V. Efficacy of Trichoderma harzianum after multiplication on different substrates in the control of root rot fungi. Int. J. Biol. Biotechnol. 2005, 2, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Etebarian, H.R.; Scott, E.S.; Wicks, T.J. Trichoderma harzianum T39 and T. virens DAR 74290 as Potential Biological Control Agents for Phytophthora erythroseptica. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2000, 106, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhammadiev, R.S.; Skvortsov, E.V.; Valiullin, L.R.; Glinushkin, A.P.; Bagaeva, T.V. Isolation, Purification, and Characterization of a Lectin from the Fungus Fusarium solani 4. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2021, 57, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C. The Genus Fusarium; Commonwealth Mycological Institute: Surrey, UK, 1985; 237p. [Google Scholar]

- Elad, Y.; Chet, I.; Henis, Y. A selective medium for improving quantitative isolation of Trichoderma spp. from soil. Phytoparasitica 1981, 9, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, M.; Datta, S.; Mehta, J.; Naruka, R.; Makhijani, K.; Sharma, G. Isolation, characterization and biomass production of Trichoderma viride using various agro products—A biocontrol agent. Arch. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 3950–3955. [Google Scholar]

- Tuite, J. Plant Pathological Methods; Fungi and Bacteria Burgess Pub. Co.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996; 293p. [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek, C.P.; Harman, G.E. Trichoderma and Gliocladium (Vol. I). Basic Biology, Taxonomy and Genetics; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Boulos, L. Flora of Egypt; All Hadara Publishing: Cairo, Egypt, 1999–2005; Volumes 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, G.; Abdallah, L.; Abdal Rahim, A.; Othman, R.; Barakat, A. Selected wild plants ethanol extract bioactivity effect on the coagulation cascade. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2017, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, N.E.; Kassem, H.A.; Hamed, M.A.; El-Feky, A.M.; Elnaggar, M.A.A.; Mahmoud, K. Isolation and characterization of the bioactive metabolites from the soil derived fungus Trichoderma viride. Mycology 2018, 9, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishal, E.M.; Mohd, I.B.; Razak, A.; Bohari, N.H.; Nasir, M.A.A.M. In vitro screening of endophytic Trichoderma sp. isolated from oil palm in FGV plantation against Ganoderma boninense. Adv. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boller, T.; Mauch, F. Colorimetric assay of Chitinase. Methods Enzymol. 1988, 161, 431–435. [Google Scholar]

- Reissig, J.L.; Strominger, J.L.; Lefloir, L.F. A modified colorimetric method for the estimation of N-acetyl amino sugars. J. Biol. Chem. 1955, 217, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collmer, A.; Reid, J.L.; Mount, M.S. Assay methods for pectic enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 1988, 161, 329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.L.; Blum, R.; Glennon, W.E.; Burton, A.L. Measurement of carboxymethyl cellulase activity. Anal. Biochem. 1960, 2, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, C.P.; Singh, S.P. Plant Enzymology and Histoenzymology; Kalyani Publishers: Ludhiana, India, 1980; pp. 54–56, 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.P.; Takahashi, T. An improved colorimetric determination of amino acids with the use of ninhydrin. Anal. Biochem. 1966, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.J.; Biely, P.; Poutanen, K. Interlaboratory testing of methods for assay of xylanase activity. J. Biotechnol. 1992, 23, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghem, L.E.R.; Petterson, L.G. The mechanism of enzymatic cellulose degradation: Isolation and some properties of β-glucosidase form Trichderma viride. Eur. J. Biochem. 1974, 46, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Zeng, X.; Bai, L.; Jiang, X.; Li, L. Bioaccumulation and biovolatilisation of pentavalent arsenic by Penicillin janthinellum, Fusarium oxysporum and Trichoderma asperellum under laboratory conditions. Curr. Microbiol. 2010, 61, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daoud, A.; Malika, D.; Bakari, S.; Hfaiedh, N.; Mnafgui, K.; Kadri, A. Assessment of polyphenol composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of various extracts of date palm pollen (DPP) from two Tunisian cultivars. Arab. J. Chem. 2015, 12, 3075–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.M.F.; Maffia, L.A.; Casali, V.W.D.; Cardoso, A.A. In vitro effect of plant leaf extracts on mycelial growth and sclerotial germination of Sclerotiumcepivorum. J. Phytopathol. 1998, 146, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonelimali, F.D.; Lin, J.; Miao, W.; Xuan, J.; Charles, F.; Chen, M.; Hatab, S.R. Antimicrobial properties and mechanism of action of some plant extracts against food pathogens and spoilage microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneem, K.; Ali, A.A.; El-Baz, S.M. First record of plond psyllium (Plantago ovata FORSK.) Root rot and wilt diseases in egypt. J. Plant Prod. 2007, 32, 7273–7287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mohamedy, R.S.; Shafeek, M.R.; Fatma, A.R. Management of root rot diseases and improvement growth and yield of green bean plants using plant resistance inducers and biological seed treatments. J. Agric. Technol. 2015, 11, 1219–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliavini, M.; Veto, L.J.; Looney, N.E. Measuring root surface area and mean root diameter of peach seedlings by digital image analysis. Hort Sci. 1993, 28, 1129–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolates | F. oxysporum | R. solani | P. ultimum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 87.00 ± 0.57 a | 90.00 ± 0.0 a | 90.00 ± 0.0 a |

| T1 | 40.33 ± 0.33 b | 18.67 ± 0.33 d | 22.67 ± 0.33 d |

| T2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 e | 0.0 ± 0.0 e | 0.0 ± 0.0 e |

| T3 | 36.67 ± 0.33 c | 23.33 ± 0.33 b | 28.33 ± 0.33 b |

| T4 | 29.33± 0.33 d | 20.33± 0.33 c | 25.67± 0.0 c |

| LSD | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Enzymes of Trichoderma Isolate (T2) | (µmol Enzyme min−1·mg−1 Protein) | Enzymes | (µmol Enzyme min−1·mg−1 Protein) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protease | 5.65 | Polygalacturonase (PG) | 7.56 |

| β-1-3-exoglucanase | 3.22 | β-glucosidase | 3.98 |

| Chitinase | 1.93 | Xylanase | 7.30 |

| Cellulase | 3.41 | Trichorzins PA (peptaibols) μg/mL | 13.0 |

| RT | Compound | Type | Area | Area% | Antifungal Activity Against | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.58 | Gallic acid | Phenolic | 162.19 | 8.06 | Alternaria solani | [39] |

| 4.27 | Chlorogenic acid | Phenolic | 608.01 | 30.24 | Candida albicans | [40] |

| 4.61 | Catechin | Phenolic | 11.24 | 0.55 | Candida albicans | [41] |

| 5.69 | Methyl gallate | Phenolic | 32.62 | 1.62 | Magnaporthe grisea, Botrytis cinerea, and Puccinia recondita | [42] |

| 6.39 | Syringic acid | Phenolic | 20.84 | 1.03 | Ganoderma boninense | [43] |

| 6.70 | Pyrocatechol | Phenolic | 17.34 | 0.86 | Bipolaris carbonum | [44] |

| 6.86 | Rutin | Flavonoid | 26.09 | 1.29 | Fusarium solani | [45] |

| 7.47 | Ellagic acid | Phenolic | 5.76 | 0.28 | Candida krusei and Candida parapsilosis | [46] |

| 8.68 | Coumaric acid | Phenolic | 2.16 | 0.10 | Botrytis cinerea | [47] |

| 9.25 | Vanillin | Phenolic | 940.70 | 46.79 | Alternaria alternata | [48] |

| 9.85 | Ferulic acid | Phenolic | 46.86 | 2.33 | Fusarium graminearum | [49] |

| 10.5 | Naringenin | Flavonoid | 31.56 | 1.56 | Candida albicans | [50] |

| 11.5 | Rosmarinic acid | Phenolic | 2.67 | 0.13 | Candida albicans | [51] |

| 15.6 | Daidzein | Phenolic | 69.51 | 3.45 | Herpes simplex and Candida albicans | [52] |

| 17.3 | Quercetin | Phenolic | 2.79 | 0.13 | Candida albicans | [51] |

| 19.1 | Cinnamic acid | Phenolic | 11.14 | 0.55 | Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus, and Aspergillus niger | [53] |

| 20.5 | Kaempferol | Phenolic | 1.74 | 0.08 | Fusarium oxysporium | [54] |

| 21.0 | Hesperetin | Flavonoid | 17.21 | 0.85 | Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis | [55] |

| Treatment | Growth Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R.L. (cm) | R.F.W. (gm) | R.D.W. (gm) | S.L. (cm) | S.F.W. (gm) | S.D.W. (gm) | Leaf Numbers | |

| C | 20.67 ± 0.33 b | 5.29 ± 0.22 b | 2.59 ± 0.19 b | 27.33 ± 0.30 b | 14.10 ± 0.25 b | 7.12 ± 0.0.20 b | 9.67 ± 0.27 b |

| P | 10.33 ± 0.33 d | 1.58 ± 0.22 d | 0.63 ± 0.19 c | 14.27 ± 0.30 e | 4.57 ± 0.25 d | 2.47 ± 0.20 d | 5.33 ± 0.27 e |

| P + F | 16.67 ± 0.33 c | 3.58 ± 0.22 c | 2.33 ± 0.19 b | 24.33 ± 0.30 c | 12.33 ± 0.25 c | 5.53 ± 0.20 c | 7.33 ± 0.27 d |

| P + T | 21.67 ± 0.33 b | 4.09 ± 0.22 c | 2.46 ± 0.19 b | 26.43 ± 0.30 b | 13.43 ± 0.25 b | 6.69 ± 0.20 b | 9.00 ± 0.27 b |

| P + E | 16.33 ± 0.33 c | 3.57 ± 0.22 c | 2.12 ± 0.19 b | 23.23 ± 0.30 d | 12.53 ± 0.25 c | 5.56 ± 0.20 c | 8.67 ± 0.27 c |

| P + T + E | 23.67 ± 0.33 a | 7.54 ± 0.22 a | 3.45 ± 0.19 a | 28.27 ± 0.30 a | 15.60 ± 0.25 a | 8.57 ± 0.20 a | 11.00 ± 0.27 a |

| LSD | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.00 |

| Root Length | Root Fresh Weight | Root Dry Weight | Shoot Length | Shoot Fresh Weight | Shoot Dry Weight | Leaf Numbers | Root Surface | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root length | 1 | |||||||

| Root fresh weight | 0.890 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Root dry weight | 0.909 ** | 0.877 ** | 1 | |||||

| Shoot length | 0.946 ** | 0.830 ** | 0.914 ** | 1 | ||||

| Shoot fresh weight | 0.925 ** | 0.847 ** | 0.924 ** | 0.984 ** | 1 | |||

| Shoot dry weight | 0.968 ** | 0.929 ** | 0.927 ** | 0.952 ** | 0.954 ** | 1 | ||

| Leaf numbers | 0.919 ** | 0.909 ** | 0.854 ** | 0.889 ** | 0.905 ** | 0.951 ** | 1 | |

| Root surface | 0.884 ** | 0.759 ** | 0.851 ** | 0.852 ** | 0.857 ** | 0.858 ** | 0.816 ** | 1 |

| Isolates | Latitude and Longitude | Location of Host Plant |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | 30°38′41.9″ N 30°06′53.9″ E | Nubaria |

| T2 | 30°39′37″ N 30°04′03″ E | Sadat City |

| T3 | 30°13′04″ N 30°51′51″ E | El Khatatba |

| T4 | 30°42′01″ N 30°02′50″ E | Alex. Cairo Road K. 76. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nofal, A.M.; Hamouda, R.A.; Rizk, A.; El-Rahman, M.A.; Takla, A.K.; Galal, H.; Alqahtani, M.D.; Alharbi, B.M.; Elkelish, A.; Shaheen, S. Polyphenols-Rich Extract of Calotropis procera Alone and in Combination with Trichoderma Culture Filtrate for Biocontrol of Cantaloupe Wilt and Root Rot Fungi. Molecules 2024, 29, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29010139

Nofal AM, Hamouda RA, Rizk A, El-Rahman MA, Takla AK, Galal H, Alqahtani MD, Alharbi BM, Elkelish A, Shaheen S. Polyphenols-Rich Extract of Calotropis procera Alone and in Combination with Trichoderma Culture Filtrate for Biocontrol of Cantaloupe Wilt and Root Rot Fungi. Molecules. 2024; 29(1):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29010139

Chicago/Turabian StyleNofal, Ashraf M., Ragaa A. Hamouda, Amira Rizk, Mohamed Abd El-Rahman, Adel K. Takla, Hoda Galal, Mashael Daghash Alqahtani, Basmah M. Alharbi, Amr Elkelish, and Sabery Shaheen. 2024. "Polyphenols-Rich Extract of Calotropis procera Alone and in Combination with Trichoderma Culture Filtrate for Biocontrol of Cantaloupe Wilt and Root Rot Fungi" Molecules 29, no. 1: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29010139

APA StyleNofal, A. M., Hamouda, R. A., Rizk, A., El-Rahman, M. A., Takla, A. K., Galal, H., Alqahtani, M. D., Alharbi, B. M., Elkelish, A., & Shaheen, S. (2024). Polyphenols-Rich Extract of Calotropis procera Alone and in Combination with Trichoderma Culture Filtrate for Biocontrol of Cantaloupe Wilt and Root Rot Fungi. Molecules, 29(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29010139