The Dynamical Asymmetry in SARS-CoV2 Protease Reveals the Exchange Between Catalytic Activity and Stability in Homodimers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Structure Identification

2.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

2.3. Molecular Dynamics Analysis

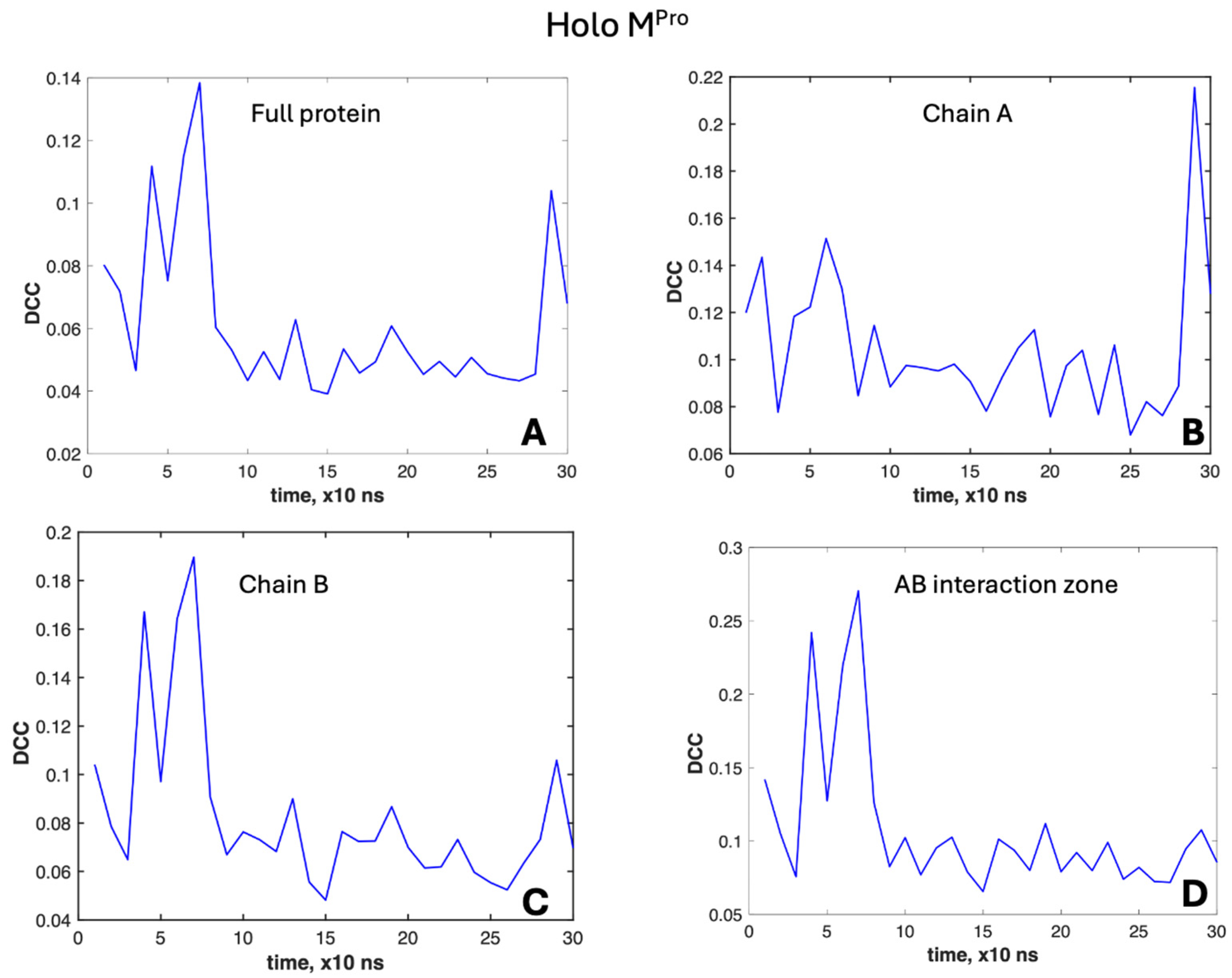

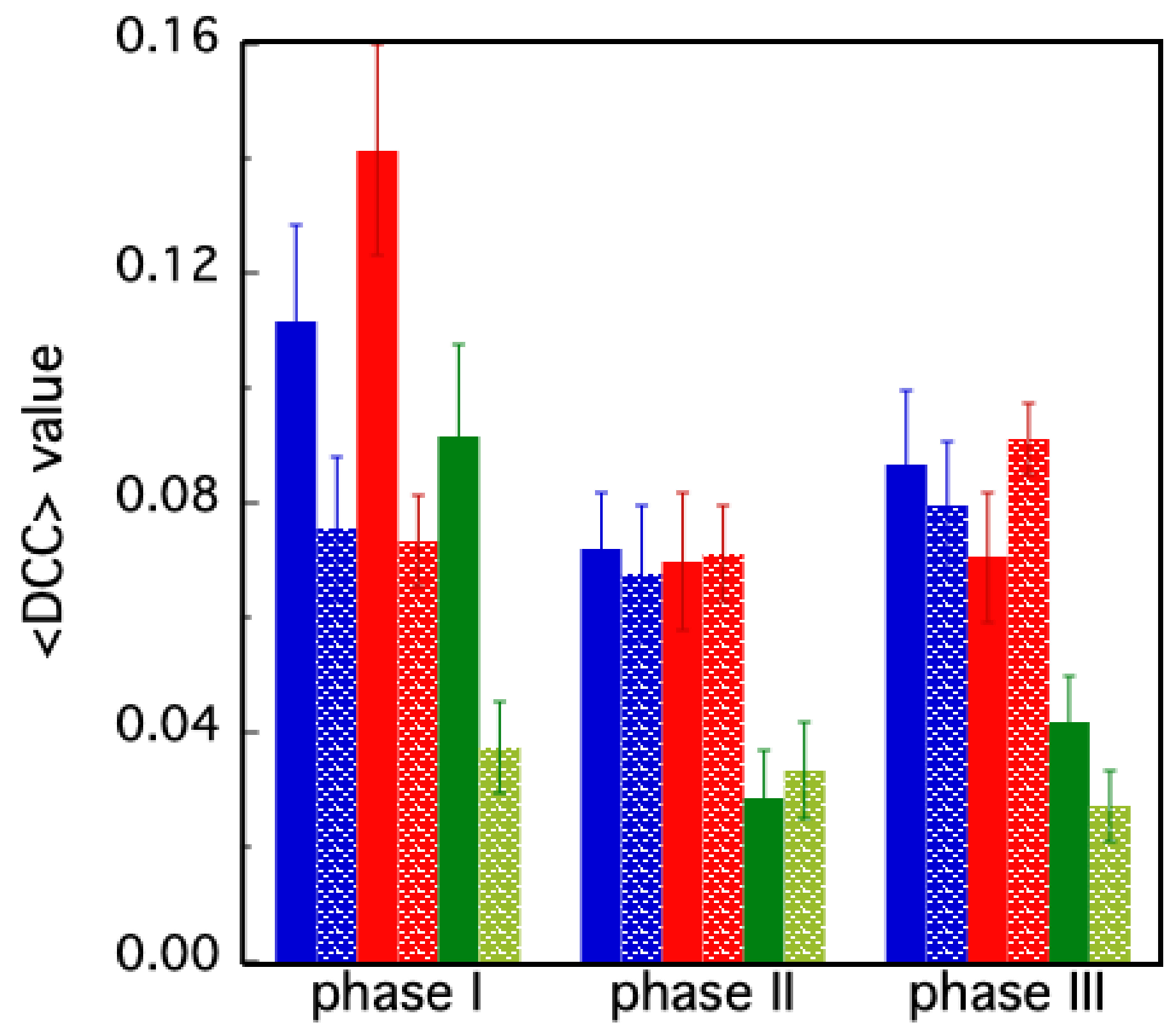

2.3.1. DCC Analysis

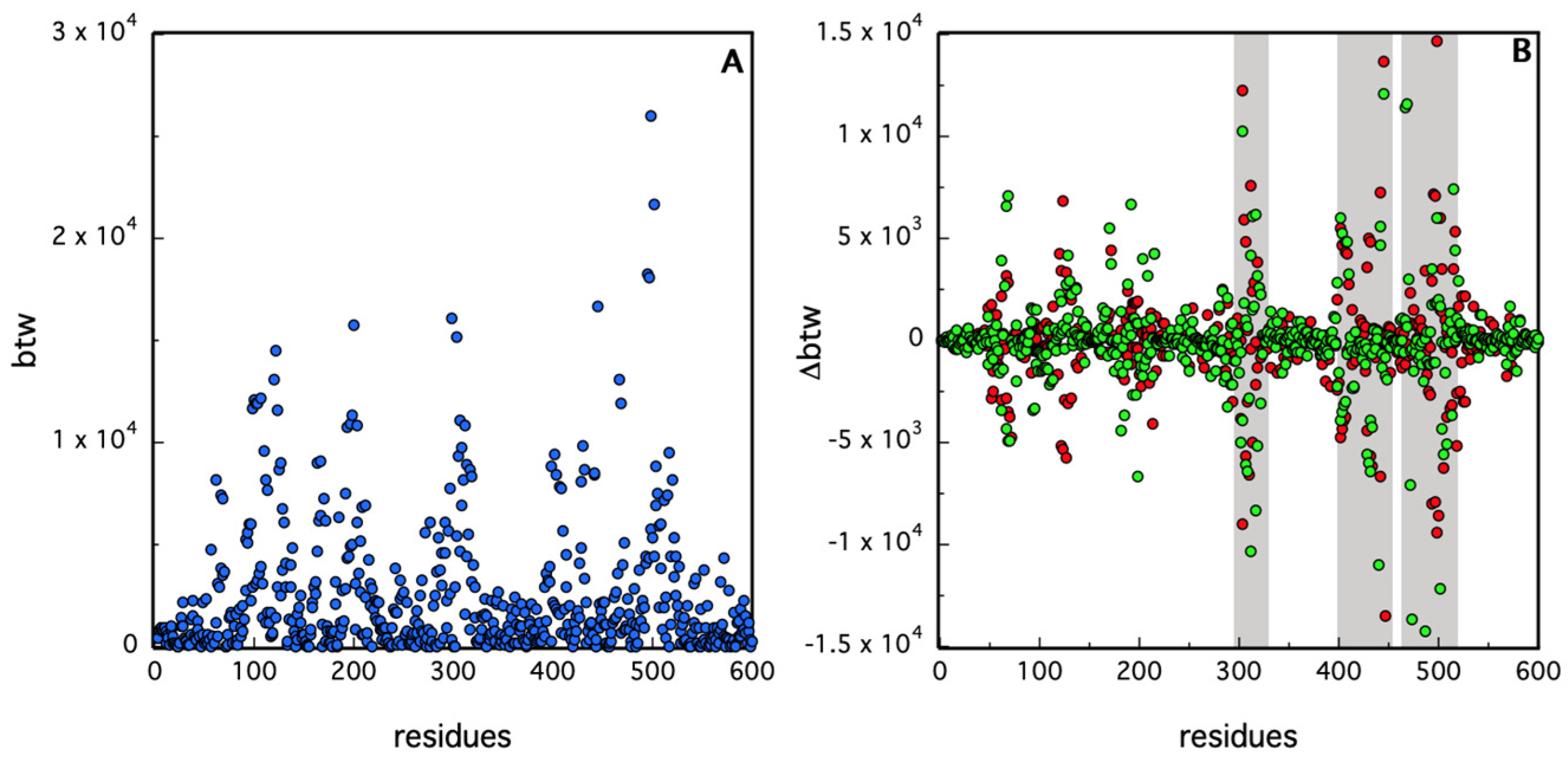

2.3.2. Protein Contact Network Analysis

3. Results

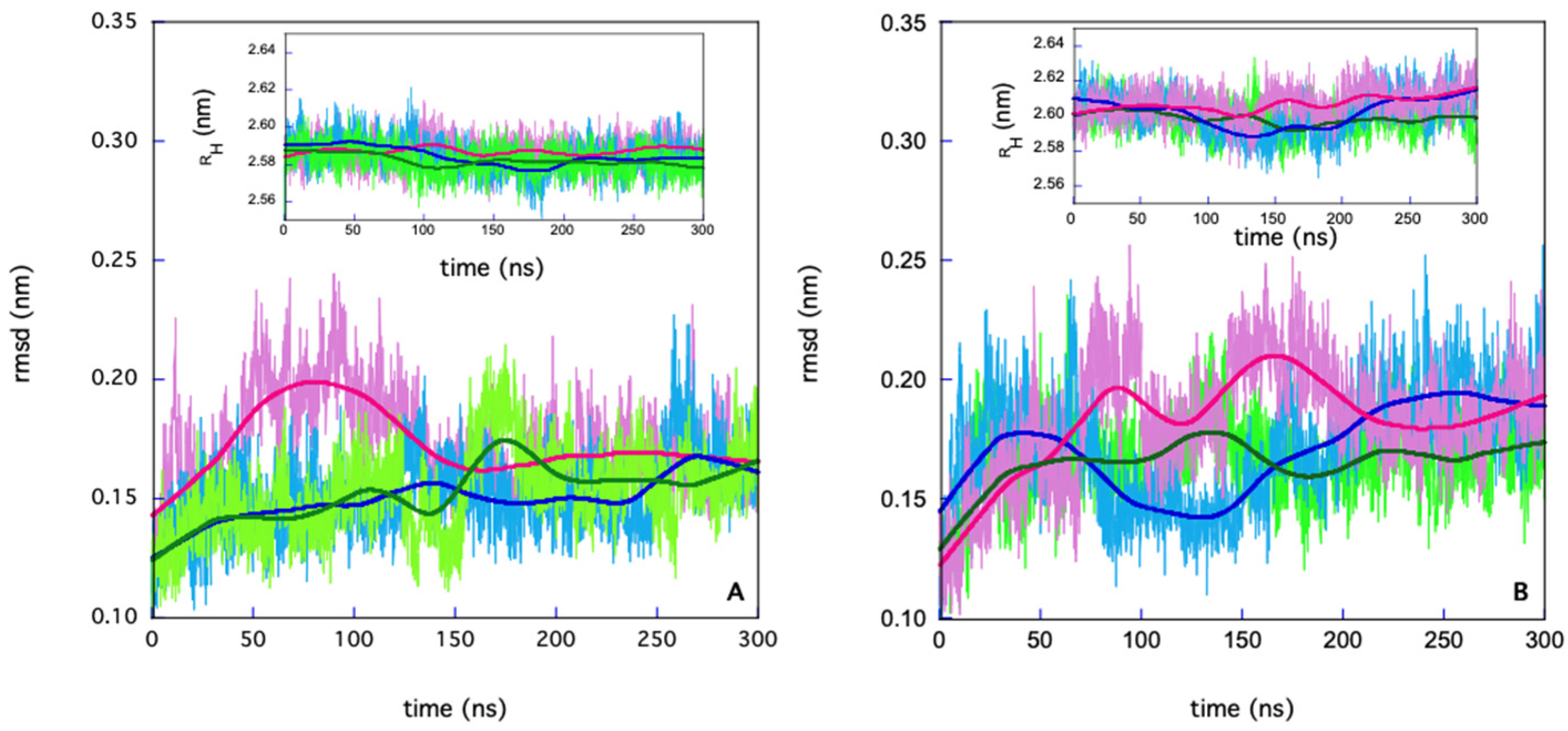

- PHASE I: in the first 72 ns, both chains retain their substrates; at t ≈ 72 ns, chain B loses its substrate;

- PHASE II: from t ≈ 72 ns to 200 ns, only chain A retains its substrate; at t = 200 ns, chain A also loses its substrate;

- PHASE III: from t = 200 ns, both chains are unbound.

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zeng, X.; He, B.; Cheng, W. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2: Open the door for novel therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Parida, P.K.; Paul, D.; Chakravorty, D. The natural way forward: Molecular dynamics simulation analysis of phytochemicals from Indian medicinal plants as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 targets. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 3420–3433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, G.-H.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Zhang, Y.W.; Huang, P.; Ge, G.B. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro): Structure, function, and emerging therapies for COVID-19. MedComm 2022, 3, e151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, H. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2023, 82, 102667. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, K.; Ciupak, O.; Daśko, M.; Rachon, J.; Flis, D.; Budka, J.; Inkielewicz-Stępniak, I.; Czaja, A.; Rak, J.; Demkowicz, S. Development of potent and effective SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors based on maleimide analogs for the potential treatment of COVID-19. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2024, 39, 2290910. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X.; Xu, Z.; Shao, M.; Li, D.; Duan, Y.; Tang, J.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Structure-based discovery of dual pathway inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 entry. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7574. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, G.O.; Malik, A.; Alonazi, M.; Khan, J.M.; Alhomida, A.S.; Khan, M.S.; Alenad, A.M.; Altwaijry, N.; Alafaleq, N.O. Expression, purification, and biophysical characterization of recombinant MERS-CoV main (Mpro) protease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 984–990. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestrini, L.; Belhaj, N.; Comez, L.; Gerelli, Y.; Lauria, A.; Libera, V.; Mariani, P.; Marzullo, P.; Ortore, M.G.; Piccionello, A.P.; et al. The dimer-monomer equilibrium of SARS-CoV-2 main protease is affected by small molecule inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9283. [Google Scholar]

- Nashed, N.T.; Aniana, A.; Chiliveri, R.G.S.C.; Louis, J.M. Modulation of the monomer-dimer equilibrium and catalytic activity of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by a transition-state analog inhibitor. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 160. [Google Scholar]

- Fornasier, E.; Fabbian, S.; Shehi, H.; Enderle, J.; Gatto, B.; Volpin, D.; Biondi, B.; Bellanda, M.; Giachin, G.; Sosic, A.; et al. Allostery in homodimeric SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1435. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Rao, Z. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goyal, B.; Goyal, D. Targeting the Dimerization of the Main Protease of Coronaviruses: A Potential Broad-Spectrum Therapeutic Strategy. ACS Comb. Sci. 2020, 22, 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Alzyoud, L.; Ghattas, M.A.; Atatreh, N. Allosteric binding sites of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Potential targets for broad-spectrum anti-Coronavirus agents. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2022, 16, 2463–2478. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Wei, P.; Huang, C.; Tan, L.; Liu, Y.; Lai, L. Only one protomer is active in the dimer of SARS 3C-like proteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 13894–13898. [Google Scholar]

- Iida, S.; Fukunishi, Y. Asymmetric dynamics of dimeric SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV main proteases in an apo form: Molecular dynamics study on fluctuations of active site, catalytic dyad, and hydration water. BBA Adv. 2021, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adcock, S.A.; McCammon, J.A. Molecular dynamics: Survey of methods for simulating the activity of proteins. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 1589–1615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karplus, M.; Petsko, G.A. Molecular dynamics simulations in biology. Nature 1990, 347, 631–639. [Google Scholar]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 014101. [Google Scholar]

- Karplus, M. Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 321–323. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, G.; Chauhan, M.S.; Sharma, D. In silico study of inhibition activity of boceprevir drug against 2019-nCoV main protease. Z. Naturforschung C 2024, 79, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekaari, A.; Jafari, M. Structural dynamics of COVID-19 main protease. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1223, 129235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dehury, B.; Raina, V.; Misra, N.; Suar, M. Effect of mutation on structure, function and dynamics of receptor binding domain of human SARS-CoV-2 with host cell receptor ACE2: A molecular dynamics simulations study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 7231–7245. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi-Alijanvand, H.; Di Paola, L.; Hu, G.; Leitner, D.M.; Verkhivker, G.M.; Sun, P.; Poudel, H.; Giuliani, A. Biophysical Insight into the SARS-CoV2 Spike–ACE2 Interaction and Its Modulation by Hepcidin through a Multifaceted Computational Approach. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 17024–17042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ray, D.; Le, L.; Andricioaei, I. Distant Residues Modulate Conformational Opening in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Cold Spring Harb. Lab. 2021, 118, e2100943118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brielle, E.S.; Schneidman-Duhovny, D.; Linial, M. The SARS-CoV-2 exerts a distinctive strategy for interacting with the ACE2 human receptor. Viruses 2020, 12, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A.M.; Khaleeq, A.; Syeda, H. Elucidation of cellular targets and exploitation of the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 for vaccine and monoclonal antibody synthesis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2792–2803. [Google Scholar]

- Turoňová, B.; Sikora, M.; Schürmann, C.; Hagen, W.J.H.; Welsch, S.; Blanc, F.E.C.; von Bülow, S.; Gecht, M.; Bagola, K.; Hörner, C.; et al. In situ structural analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike reveals flexibility mediated by three hinges. Science 2020, 370, 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Vijayan, R. Dynamics of the ACE2-SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV spike protein interface reveal unique mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, M.; Sormani, G.; Rodriguez, A.; Laio, A. Candidate binding sites for allosteric inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease from the analysis of large-scale molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Göhl, M.; Zhang, L.; El Kilani, H.; Sun, X.; Zhang, K.; Brönstrup, M.; Hilgenfeld, R. From repurposing to redesign: Optimization of boceprevir to highly potent inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Molecules 2022, 27, 4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, S. HCV: The Journey from Discovery to a Cure. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 31, 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Kneller, D.W.; Li, H.; Phillips, G.; Weiss, K.L.; Zhang, Q.; Arnould, M.A.; Jonsson, C.B.; Surendranathan, S.; Pavathareddy, J.; Blakeley, M.P.; et al. Covalent narlaprevir- and boceprevir-derived hybrid inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichiye, T.; Karplus, M. Collective motions in proteins: A covariance analysis of atomic fluctuations in molecular dynamics and normal mode simulations. Proteins 1991, 11, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, O.F.; Grubmüller, H. Full correlation analysis of conformational protein dynamics. Proteins 2008, 70, 1294–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Golden, L.C.; Lopez, J.A.; Shepherd, T.R.; Yu, L.; Fuentes, E.J. Conformational Dynamics and Cooperativity Drive the Specificity of a Protein-Ligand Interaction. Biophys. J. 2019, 116, 2314–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, R.B.; Zhu, X.; Shim, J.; Lopes, P.E.M.; Mittal, J.; Feig, M.; Mackerell, A.D., Jr. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ(1) and χ(2) dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3257–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; Hatcher, E.; Acharya, C.; Kundu, S.; Zhong, S.; Shim, J.; Darian, E.; Guvench, O.; Lopes, P.; Vorobyov, I.; et al. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; Raman, E.P.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. Automation of the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) II: Assignment of bonded parameters and partial atomic charges. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 3155–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. Automation of the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) I: Bond perception and atom typing. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 3144–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; Postma, J.P.M.; van Gunsteren, W.F.; DiNola, A.; Haak, J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.C.; Fraaije, J.G.E.M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- Briki, F.; Genest, D. Canonical analysis of correlated atomic motions in DNA from molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys. Chem. 1994, 52, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCammon, J.A. Protein dynamics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1984, 47, 1. [Google Scholar]

- da Penha Valente, R.P.; de Souza, R.C.; de Medeiros Muniz, G.; Ferreira, J.E.V.; de Miranda, R.M.; Lima, A.H.L.E.; da Silva Gonçalves Vianez, J.L., Jr. Using Accelerated Molecular Dynamics Simulation to elucidate the effects of the T198F mutation on the molecular flexibility of the West Nile virus envelope protein. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9625. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paola, L.; Mei, G.; Di Venere, A.; Giuliani, A. Disclosing Allostery Through Protein Contact Networks. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2253, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, E.D.; Erba, E.B.; Robinson, C.V.; Teichmann, S.A. Assembly reflects evolution of protein complexes. Nature 2008, 453, 1262–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Perica, T.; Chothia, C.; Teichmann, S.A. Evolution of oligomeric state through geometric coupling of protein interfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8127–8132. [Google Scholar]

- Changeux, J.-P. Allostery and the Monod-Wyman-Changeux model after 50 years. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2012, 41, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Mehrabi, P.; Ren, Z.; Sljoka, A.; Ing, C.; Bezginov, A.; Ye, L.; Pomès, R.; Prosser, R.S.; Pai, E.F. The role of dimer asymmetry and protomer dynamics in enzyme catalysis. Science 2017, 355, eaag2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, P.; Di Pietrantonio, C.; Kim, T.H.; Sljoka, A.; Taverner, K.; Ing, C.; Kruglyak, N.; Pomès, R.; Pai, E.F.; Prosser, R.S. Substrate-Based allosteric Regulation of a homodimeric enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 11540–11556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, T.S.; Okimoto, N.; Koyama, Y.M.; Hirano, Y.; Morimoto, G.; Ohno, Y.; Taiji, M. Drug binding dynamics of the dimeric SARS-CoV-2 main protease, determined by molecular dynamics simulation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, C.; Feys, J.R. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitors: Achieved Diversity, Developing Resistance and Future Strategies. Future Pharmacol. 2023, 3, 80–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Bascompte, J.; Brock, W.A.; Brovkin, V.; Carpenter, S.R.; Dakos, V.; Held, H.; van Nes, E.H.; Rietkerk, M.; Sugihara, G. Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature 2009, 461, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauenfelder, H.; Wolynes, P.G. Biomolecules: Where the physics of complexity and simplicity meet. Phys. Today 1994, 47, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Minicozzi, V.; Giuliani, A.; Mei, G.; Domenichelli, L.; Parise, M.; Di Venere, A.; Di Paola, L. The Dynamical Asymmetry in SARS-CoV2 Protease Reveals the Exchange Between Catalytic Activity and Stability in Homodimers. Molecules 2025, 30, 1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30071412

Minicozzi V, Giuliani A, Mei G, Domenichelli L, Parise M, Di Venere A, Di Paola L. The Dynamical Asymmetry in SARS-CoV2 Protease Reveals the Exchange Between Catalytic Activity and Stability in Homodimers. Molecules. 2025; 30(7):1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30071412

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinicozzi, Velia, Alessandro Giuliani, Giampiero Mei, Leonardo Domenichelli, Mauro Parise, Almerinda Di Venere, and Luisa Di Paola. 2025. "The Dynamical Asymmetry in SARS-CoV2 Protease Reveals the Exchange Between Catalytic Activity and Stability in Homodimers" Molecules 30, no. 7: 1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30071412

APA StyleMinicozzi, V., Giuliani, A., Mei, G., Domenichelli, L., Parise, M., Di Venere, A., & Di Paola, L. (2025). The Dynamical Asymmetry in SARS-CoV2 Protease Reveals the Exchange Between Catalytic Activity and Stability in Homodimers. Molecules, 30(7), 1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30071412