Hydrodynamic Behavior of the Intrinsically Disordered Potyvirus Protein VPg, of the Translation Initiation Factor eIF4E and of their Binary Complex

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

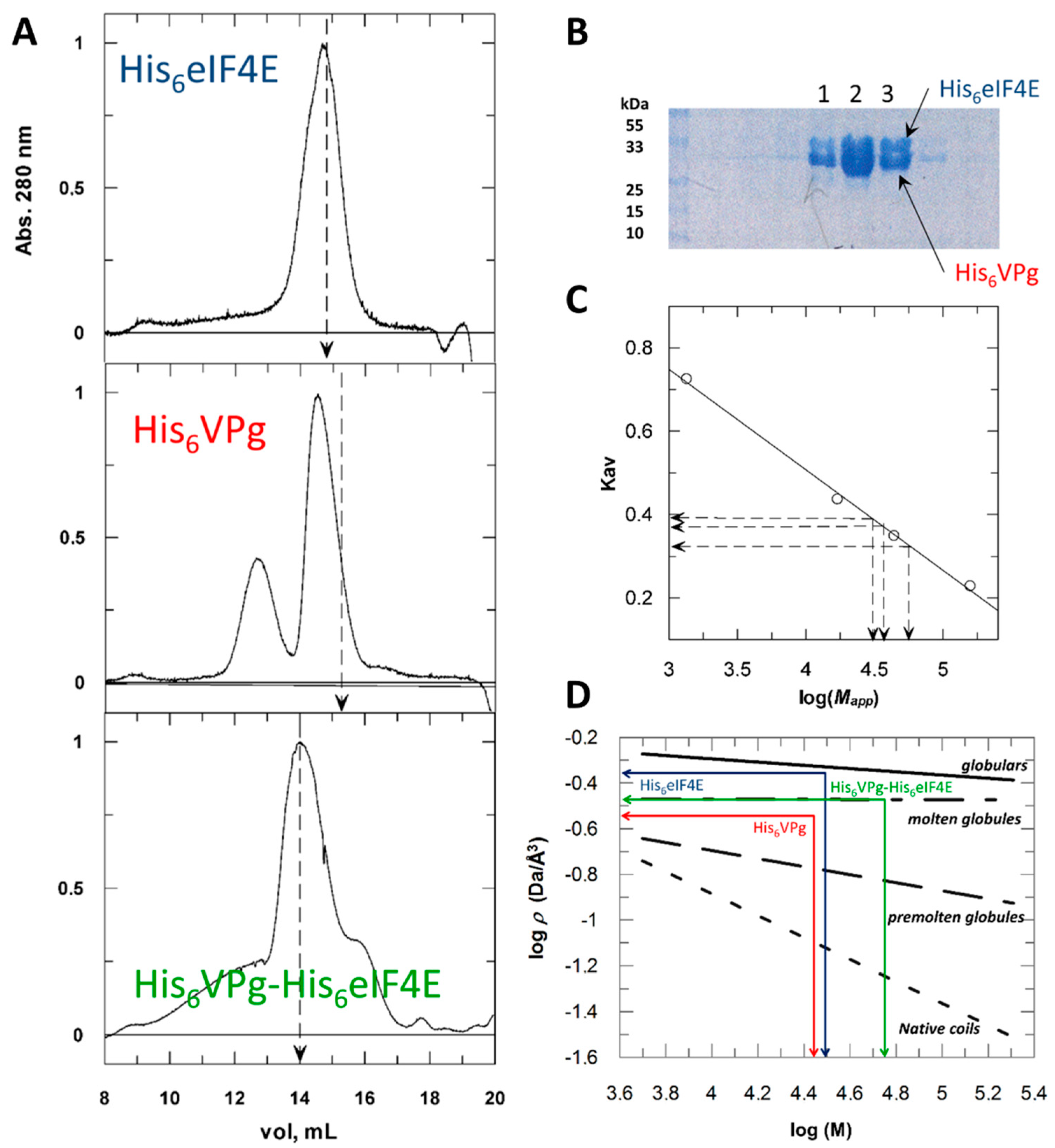

2.1. Hydrodynamic Behavior of the Histidine Tagged Forms Assessed by Size Exclusion Chromatography

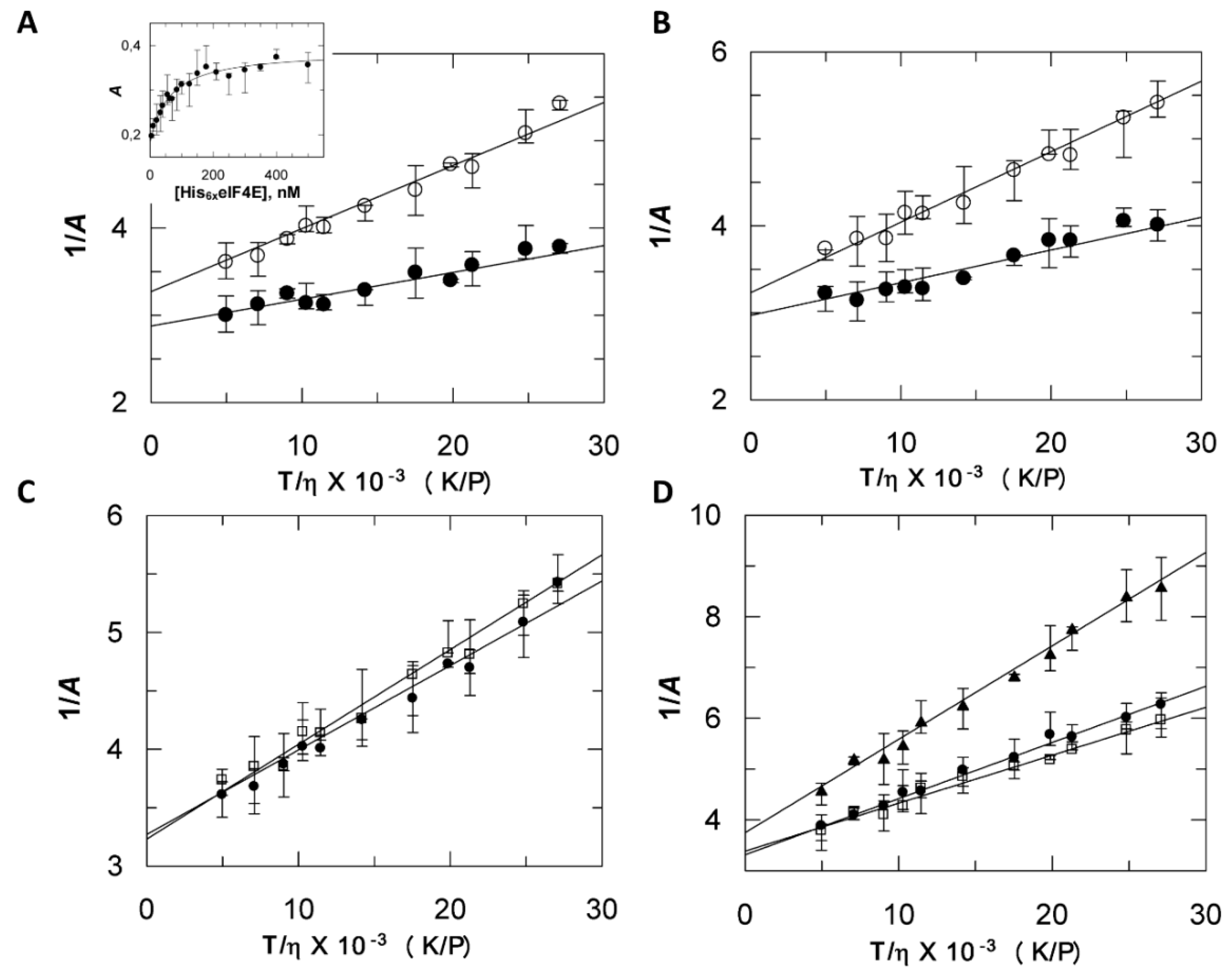

2.2. His Tagging Modulates Proteins Hydrodynamic Parameters

2.3. Discrepancies between SEC and Fluorescence Anisotropy Suggest a Contribution of Tags in Proteins Hydrodynamic Behavior

2.4. His6 VPg* and His6 VPg*-His6 eIF4E Binary Complex Shapes Differ from the Globular State

2.5. Compaction and Hydration are Experimentally Correlated

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Protein Preparation

4.2. Size Exclusion Chromatography

4.3. Hydrodynamic Radius Measure

4.4. Structural Feature Estimation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LMV | Lettuce mosaic virus |

| PVY | Potato virus Y |

| TEV | Tobacco etch virus |

| TuMV | Turnip mosaic virus |

| IAEDANS | N-(iodoacetyl)-N′-(5-sulfo-1-naphtyl)ethylenediamine |

| AEDANS | N-(acetyl)-N′-(5-sulfo-1-naphtyl)ethylenediamine |

| His6 eIF4E | N-ter hexahistidine tagged lettuce eIF4E |

| His6 VPg | N-ter hexahistidine tagged LMV VPg |

| eIF4EΔ1–46 | untagged lettuce eIF4E deleted from its first 46 N-ter amino acid |

| His6 VPg* | AEDANS labelled N-ter hexahistidine tagged LMV VPg |

| His6 eIF4E | AEDANS labelled N-ter hexahistidine tagged lettuce eIF4E |

| eIF4E* | AEDANS labelled untagged lettuce eIF4E |

| eIF4EΔ1–46* | AEDANS labelled untagged lettuce eIF4E deleted from its first 46 N-ter amino acids |

| [His6 VPg*-His6 eIF4E] | AEDANS labelled binary complex |

References

- Boehr, D.D.; Wright, P.E. Biochemistry. How do proteins interact? Science 2018, 320, 1429–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habchi, J.; Tompa, P.; Longhi, S.; Uversky, V.N. Introducing Protein Intrinsic Disorder. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6561–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Blocquel, D.; Habchi, J.; Uversky, A.V.; Kurgan, L.; Uversky, V.N.; Longhi, S. Structural Disorder in Viral Proteins. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6880–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushker, R.; Mooney, C.; Davey, N.E.; Jacqué, J.-M.; Shields, D.C. Marked Variability in the Extent of Protein Disorder within and between Viral Families. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Dunker, A.K.; Uversky, V.N. Orderly order in protein intrinsic disorder distribution: Disorder in 3500 proteomes from viruses and the three domains of life. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2012, 30, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.; Zerbini, F.; French, R.; Rabenstein, F.; Stenger, D.; Valkonen, J. Potyviridae. Virus Taxonomy, 9th Report of the International Committee for Taxonomy of Viruses; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.F.; Klein, P.G.; Hunt, A.G.; Shaw, J.G. Replacement of the tyrosine residue that links a potyviral VPg to the viral RNA is lethal. Virology 1996, 220, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.F.; Rychlik, W.; Rhoads, R.E.; Hunt, A.G.; Shaw, J.G. A tyrosine residue in the small nuclear inclusion protein of tobacco vein mottling virus links the VPg to the viral RNA. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 511–513. [Google Scholar]

- Hebrard, E.; Bessin, Y.; Michon, T.; Longhi, S.; Uversky, V.N.; Delalande, F.; Van Dorsselaer, A.; Romero, P.; Walter, J.; Declerck, N.; et al. Intrinsic disorder in Viral Proteins Genome-Linked: Experimental and predictive analyses. Virol. J. 2009, 6, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Grzela, R.; Szolajska, E.; Ebel, C.; Madern, D.; Favier, A.; Wojtal, I.; Zagorski, W.; Chroboczek, J. Virulence Factor of Potato Virus Y, Genome-attached Terminal Protein VPg, Is a Highly Disordered Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rantalainen, K.I.; Uversky, V.N.; Permi, P.; Kalkkinen, N.; Dunker, A.K.; Makinen, K. Potato virus A genome-linked protein VPg is an intrinsically disordered molten globule-like protein with a hydrophobic core. Virology 2008, 377, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Laliberte, J.F. The genome-linked protein VPg of plant viruses-a protein with many partners. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, F.; Rodrigo, G.; Aragonés, V.; Ruiz, M.; Lodewijk, I.; Fernández, U.; Elena, S.F.; Daròs, J.-A. Interaction network of tobacco etch potyvirus NIa protein with the host proteome during infection. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, C.; Nicolaï, M.; Gallois, J.L.; Robaglia, C.; Moury, B.; Palloix, A.; Caranta, C. Natural variation and functional analyses provide evidence for co-evolution between plant eIF4E and potyviral VPg. Plant J. 2008, 54, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, S.; Plante, D.; Wittmann, S.; Daigneault, N.; Fortin, M.G.; Laliberte, J.F. Complex formation between potyvirus VPg and translation eukaryotic initiation factor 4E correlates with virus infectivity. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 7730–7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robaglia, C.; Caranta, C. Translation initiation factors: A weak link in plant RNA virus infection. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moury, B.; Charron, C.; Janzac, B.; Simon, V.; Gallois, J.L.; Palloix, A.; Caranta, C. Evolution of plant eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) and potyvirus genome-linked protein (VPg): A game of mirrors impacting resistance spectrum and durability. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 27, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayme, V.; Souche, S.; Caranta, C.; Jacquemond, M.; Chadoeuf, J.; Palloix, A.; Moury, B. Different mutations in the genome-linked protein VPg of potato virus Y confer virulence on the pvr2(3) resistance in pepper. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayme, V.; Petit-Pierre, J.; Souche, S.; Palloix, A.; Moury, B. Molecular dissection of the potato virus Y VPg virulence factor reveals complex adaptations to the pvr2 resistance allelic series in pepper. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudet-Tavert, G.; Michon, T.; Walter, J.; Delaunay, T.; Redondo, E.; Le Gall, O. Central domain of a potyvirus VPg is involved in the interaction with the host translation initiation factor eIF4E and the viral protein HcPro. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charon, J.; Theil, S.; Nicaise, V.; Michon, T. Protein intrinsic disorder within the Potyvirus genus: From proteome-wide analysis to functional annotation. Mol. BioSyst. 2016, 12, 634–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. What does it mean to be natively unfolded? Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Haar, T.; Oku, Y.; Ptushkina, M.; Moerke, N.; Wagner, G.; Gross, J.D.; McCarthy, J.E. Folding transitions during assembly of the eukaryotic mRNA cap-binding complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 356, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sabharwal, P.; Srinivas, S.; Savithri, H.S. Mapping the domain of interaction of PVBV VPg with NIa-Pro: Role of N-terminal disordered region of VPg in the modulation of structure and function. Virology 2018, 524, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzingo, A.F.; Dhaliwal, S.; Dutt-Chaudhuri, A.; Lyon, A.; Sadow, J.H.; Hoffman, D.W.; Robertus, J.D.; Browning, K.S. The structure of eukaryotic translation initiation factor-4E from wheat reveals a novel disulfide bond. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1504–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, J.A.; Stevenson, C.E.M.; Jarvis, G.E.; Lawson, D.M.; Maule, A.J. Structure-based mutational analysis of eIF4E in relation to sbm1 resistance to Pea seed-borne mosaic virus in Pea. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e15873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J.A.; Forman-Kay, J.D. Sequence determinants of compaction in intrinsically disordered proteins. Biophys. J. 2010, 98, 2374–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, M.; Johnson, D.H.; McDonald, H.; Brouillette, C.; Delucas, L.J. His-tag impact on structure. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2007, 63, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica, L.; Bessa, L.M.; Hanoulle, X.; Jensen, M.R.; Blackledge, M.; Schneider, R. Binding Mechanisms of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Theory, Simulation, and Experiment. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granon, S.; Kerfelec, B.; Chapus, C. Spectrofluorimetric investigation of the interactions between the subunits of bovine pancreatic procarboxypeptidase A-S6. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 10383–10388. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, L.; Biswas, P. Hydration Water Distribution around Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018, 122, 4206–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenal, A.; Guijarro, J.I.; Raynal, B.; Delepierre, M.; Ladant, D. RTX calcium binding motifs are intrinsically disordered in the absence of calcium: Implication for protein secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, P.; Biswas, P. Local Structure and Dynamics of Hydration Water in Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015, 119, 10858–10867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A.; Amoros, D.; Garcia de la Torre, J. Prediction of hydrodynamic and other solution properties of rigid proteins from atomic- and residue-level models. Biophys. J. 2011, 101, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.R.; Ruigrok, R.W.H.; Blackledge, M. Describing intrinsically disordered proteins at atomic resolution by NMR. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.; Tidow, H.; Rutherford, T.J.; Markwick, P.; Jensen, M.R.; Mylonas, E.; Svergun, D.I.; Blackledge, M.; Fersht, A.R. Structure of tumor suppressor p53 and its intrinsically disordered N-terminal transactivation domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosol, S.; Contreras-Martos, S.; Cedeño, C.; Tompa, P. Structural characterization of intrinsically disordered proteins by NMR spectroscopy. Molecules 2013, 18, 10802–10828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrak-Wojcik, A.; Gorka, M.; Niedzwiecka, K.; Zdanowski, K.; Zuberek, J.; Niedzwiecka, A.; Stolarski, R. Eukaryotic translation initiation is controlled by cooperativity effects within ternary complexes of 4E-BP1, eIF4E, and the mRNA 5′ cap. FEBS Lett. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michon, T.; Estevez, Y.; Walter, J.; German-Retana, S.; Le Gall, O. The potyviral virus genome-linked protein VPg forms a ternary complex with the eukaryotic initiation factors eIF4E and eIF4G and reduces eIF4E affinity for a mRNA cap analogue. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 1312–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. Natively unfolded proteins: A point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2002, 11, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Santambrogio, C.; Brocca, S.; Grandori, R. Length-dependent compaction of intrinsically disordered proteins. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Units | HV | V | HE | E | EΔ(1–46) | HVHE | VE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW | g/mol | 26,222 † | 21,781 † | 28,550 † | 26,076 † | 21,246 † | 54,772 ‡ | 47,857 ‡ |

| SEC | ||||||||

| VR | mL | 14.4 | nd | 14.8 | nd | nd | 13.7 | nd |

| Mapp | kg/mol | 38.0 ± 1.0 | nd | 30.2 ± 0.8 | nd | nd | 56.2 ± 1.5 | nd |

| Rh | Å | 28.1 ± 0.7 | nd | 26.4 ± 1.1 | nd | nd | 33.0 ± 0.9 | nd |

| ρ | g/mol·Å 3 | 0.28 | nd | 0.40 | nd | nd | 0.38 | nd |

| Conformation | MG/PMG | F/MG | MG | |||||

| 1 Fluorescence Anisotropy | ||||||||

| Vapp | L/mol | 58.7 ± 1.8 | 51.6 ± 0.2 | 42.9 ± 0.8 | 46.5 ± 1.0 | 24.3 ± 0.5 | 121.3 ± 3.2 | 102.4 ± 0.9 |

| θexp | s (×109) | 23.7 | 20.9 | 17.3 | 18.8 | 9.8 | 49 3 | 41.4 |

| θcalc | s (×109) | 9.8 | 8.9 | 10.7 | 9.8 | 7.9 | 20.6 | 18.0 |

| (θexp)/(θcalc) | 2.41 | 2.55 | 1.62 | 1.92 | 1.23 | 2.38 | 2.30 | |

| h | g water/g | 1.44 | 1.57 | 0.72 | 1 | 0.38 (0.53) 2 | 1.41 | 1.35 |

| Rh | Å | 24 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 18 | 31 | 29 |

| ρ | g/mol·Å 3 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.88 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| Molecular Species | MM, kDa * | s20,w, s (×1013) | Ref. | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPg (LMV)-R | 21.8 | 1.8 | This study | Fluorescence |

| VPg (PVY)-R | 22 | 1.7 | [10] | UAC |

| VPg (PVY) | 22 | 3.0 | [10] | UAC |

| VPg (PVBV) | 21.8 | 3.2 | [24] | UAC |

| eIF4E (lettuce) | 26.1 | 2.2 | This study | Fluorescence |

| eIF4E (human) | 24.3 | 2.03 | [38] | UAC |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walter, J.; Barra, A.; Doublet, B.; Céré, N.; Charon, J.; Michon, T. Hydrodynamic Behavior of the Intrinsically Disordered Potyvirus Protein VPg, of the Translation Initiation Factor eIF4E and of their Binary Complex. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20071794

Walter J, Barra A, Doublet B, Céré N, Charon J, Michon T. Hydrodynamic Behavior of the Intrinsically Disordered Potyvirus Protein VPg, of the Translation Initiation Factor eIF4E and of their Binary Complex. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(7):1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20071794

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalter, Jocelyne, Amandine Barra, Bénédicte Doublet, Nicolas Céré, Justine Charon, and Thierry Michon. 2019. "Hydrodynamic Behavior of the Intrinsically Disordered Potyvirus Protein VPg, of the Translation Initiation Factor eIF4E and of their Binary Complex" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 7: 1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20071794

APA StyleWalter, J., Barra, A., Doublet, B., Céré, N., Charon, J., & Michon, T. (2019). Hydrodynamic Behavior of the Intrinsically Disordered Potyvirus Protein VPg, of the Translation Initiation Factor eIF4E and of their Binary Complex. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(7), 1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20071794