Role of the Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Protein TEX101 and Its Related Molecules in Spermatogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. GPI-APs

2.1. History of the Discovery

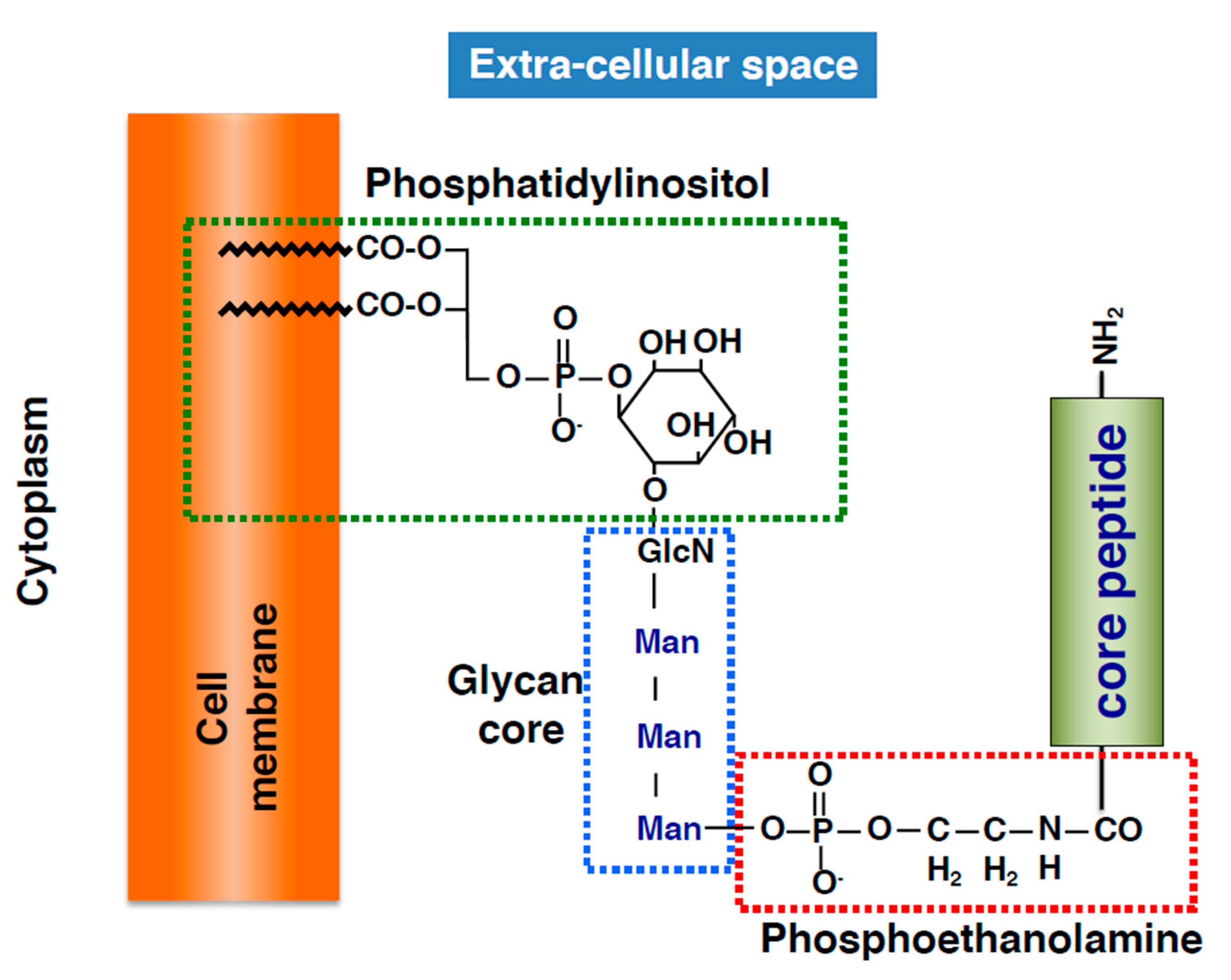

2.2. Basic Structure of GPI-APs

2.3. General Characteristics and Potential Biological Significances of GPI-APs

2.4. GPI-APs in the Testis

3. Significance of TEX101 in the Fertilization Process

3.1. Strategies for Identifying Testis-Specific Molecule(s)

3.2. Molecular Characteristics of TEX101, a Unique Glycoprotein Germ Cell Marker

3.3. Subcelllar Localization of TEX101 within Gonadal Organs

3.4. Molecules Associate with TEX101 in Male Germ Organ

3.5. TEX101 Function during Fertilization

4. Conclusions and Future Aspects

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orgebin-Crist, M.C.; Olson, G.E.; Danzo, B.J. Factor influencing maturation of spermatozoa in the epididymis. In Intragonadal Regulation of Reproduction; Franchimont, P., Channing, C.P., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1981; pp. 393–417. [Google Scholar]

- Orgebin-Crist, M.C. Androgens and epididymal function. In Pharmacology, Biology, and Clinical Application of Androgens; Bhasin, S., Gabeluick, H.L., Spieler, J.M., Swerdlott, R.S., Wang, C., Eds.; Wiley-Liss: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Orgebin-Crist, M.C. The epididymis across 24 centuries. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 1998, 53, 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, L.D.; Ettlin, R.A.; Shnha Hikim, A.P.; Clegg, E.D. Mammalian spermatogenesis. In Histological and Histopathological Evaluation of the Testis; Russell, L.D., Ed.; Cache River Press: Clearwater, FL, USA, 1990; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, M.A.J.; Hart, G.W.; Kinoshita, T. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Anchors. In Essentials of Glycobiology, 3rd ed.; Varki, A., Cummings, R.D., Esko, J.D., Stanley, P., Hart, G.W., Aebi, M., Darvill, A.G., Kinoshita, T., Packer, N.H., Prestegard, J.H., et al., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 2015–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh, G.; Tojo, H.; Nakatani, Y.; Komazawa, N.; Murata, C.; Yamagata, K.; Maeda, Y.; Kinoshita, T.; Okabe, M.; Taguchi, R.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme is a GPI-anchored protein releasing factor crucial for fertilization. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughner, C.L.; Bruford, E.A.; McAndrews, M.S.; Delp, E.E.; Swamynathan, S.; Swamynathan, S.K. Organization, evolution and functions of the human and mouse Ly6/uPAR family genes. Hum. Genom. 2016, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilyeva, N.A.; Loktyushov, E.V.; Bychkov, M.L.; Shenkarev, Z.O.; Lyukmanova, E.N. Three-Finger Proteins from the Ly6/uPAR Family: Functional Diversity within One Structural Motif. Biochemistry 2017, 82, 1702–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurita, A.; Takizawa, T.; Takayama, T.; Totsukawa, K.; Matsubara, S.; Shibahara, H.; Orgebin-Crist, M.C.; Sendo, F.; Shinkai, Y.; Araki, Y. Identification, cloning, and initial characterization of a novel mouse testicular germ cell-specific antigen. Biol. Reprod. 2001, 64, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Yoshitake, H.; Tsukamoto, H.; Takahashi, M.; Mori, M.; Takizawa, T.; Takamori, K.; Ogawa, H.; Kinoshita, K.; Araki, Y. Molecular characterization of a germ-cell-specific antigen, TEX101, from mouse testis. Zygote 2006, 14, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, H.; Yoshitake, H.; Mori, M.; Yanagida, M.; Takamori, K.; Ogawa, H.; Takizawa, T.; Araki, Y. Testicular proteins associated with the germ cell-marker, TEX101: Involvement of cellubrevin in TEX101-trafficking to the cell surface during spermatogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 345, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitake, H.; Tsukamoto, H.; Maruyama-Fukushima, M.; Takamori, K.; Ogawa, H.; Araki, Y. TEX101, a germ cell-marker glycoprotein, is associated with lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus k within the mouse testis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 372, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, T.; Mishima, T.; Mori, M.; Jin, H.; Tsukamoto, H.; Takahashi, K.; Takizawa, T.; Kinoshita, K.; Suzuki, M.; Sato, I.; et al. Sexually dimorphic expression of the novel germ cell antigen TEX101 during mouse gonad development. Biol. Reprod. 2005, 72, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slein, M.W.; Logan, G.F., Jr. Mechanism of action of the toxin of Bacillus anthracis. I. Effect in vivo on some blood serum components. J. Bacteriol. 1960, 80, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slein, M.W.; Logan, G.F., Jr. Partial purification and properties of two phospholipases of Bacillus cereus. J. Bacteriol. 1963, 85, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikezawa, H.; Yamanegi, M.; Taguchi, R.; Miyashita, T.; Ohyabu, T. Studies on phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase (phospholipase C type) of Bacillus cereus. I. purification, properties and phosphatase-releasing activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1976, 450, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohyabu, T.; Taguchi, R.; Ikezawa, H. Studies on phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase (phospholipase C type) of Bacillus cereus. II. In vivo and immunochemical studies of phosphatase-releasing activity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1978, 190, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, M.G.; Finean, J.B. Non-lytic release of acetylcholinesterase from erythrocytes by a phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. FEBS Lett. 1977, 82, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, M.G.; Finean, J.B. Specific release of plasma membrane enzymes by a phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1978, 508, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakabayashi, T.; Ikezawa, H. Release of alkaline phosphodiesterase I from rat kidney plasma membrane produced by the phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C of Bacillus thuringiensis. Cell Struct. Funct. 1984, 9, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, M.A.; Low, M.G.; Cross, G.A. Glycosyl-sn-1,2-dimyristylphosphatidylinositol is covalently linked to Trypanosoma brucei variant surface glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 14547–14555. [Google Scholar]

- Helenis, A.; Kuhlbrandt, W.; Lill, H.; Simons, K.; von Heijne, G.; Walther, T. Membrane structure. In Molecular Biology of the Cell, 6th ed.; Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Morgan, D., Raff, M., Roberts, K., Walter, P., Eds.; Garland Science: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 565–596. [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, T.; Fujita, M. Biosynthesis of GPI-anchored proteins: Special emphasis on GPI lipid remodeling. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, D.; Kashiwabara, S.; Honda, A.; Yamagata, K.; Wu, Q.; Ikawa, M.; Okabe, M.; Baba, T. Mouse sperm lacking cell surface hyaluronidase PH-20 can pass through the layer of cumulus cells and fertilize the egg. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 30310–30314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzel-Arnett, S.; Bugge, T.H.; Hess, R.A.; Carnes, K.; Stringer, B.W.; Scarman, A.L.; Hooper, J.D.; Tonks, I.D.; Kay, G.F.; Antalis, T.M. The glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored serine protease PRSS21 (testisin) imparts murine epididymal sperm cell maturation and fertilizing ability. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 81, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, Y.; Tokuhiro, K.; Muro, Y.; Kondoh, G.; Araki, Y.; Ikawa, M.; Okabe, M. Expression of TEX101, regulated by ACE, is essential for the production of fertile mouse spermatozoa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8111–8116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyetko, M.R.; Todd, R.F., 3rd; Wilkinson, C.C.; Sitrin, R.G. The urokinase receptor is required for human monocyte chemotaxis in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 93, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Watanabe, T.; Sakurai, S.; Ohtake, K.; Kinoshita, T.; Araki, A.; Fujita, T.; Takei, H.; Takeda, Y.; Sato, Y.; et al. A novel glycosylphosphatidyl inositol-anchored protein on human leukocytes: A possible role for regulation of neutrophil adherence and migration. J. Immunol. 1999, 162, 4277–4284. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Buono, N.; Parrotta, R.; Morone, S.; Bovino, P.; Nacci, G.; Ortolan, E.; Horenstein, A.L.; Inzhutova, A.; Ferrero, E.; Funaro, A. The CD157-integrin partnership controls transendothelial migration and adhesion of human monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 18681–18691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paratcha, G.; Ledda, F.; Ibanez, C.F. The neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM is an alternative signaling receptor for GDNF family ligands. Cell 2003, 113, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.Y.; David, S. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored ceruloplasmin is required for iron efflux from cells in the central nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27144–27148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Wang, S.M.; Yang, S.H.; Jeng, C.J. Role of Thy-1 in in vivo and in vitro neural development and regeneration of dorsal root ganglionic neurons. J. Cell. Biochem. 2005, 94, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedrahita, J.A.; Oetama, B.; Bennett, G.D.; van Waes, J.; Kamen, B.A.; Richardson, J.; Lacey, S.W.; Anderson, R.G.; Finnell, R.H. Mice lacking the folic acid-binding protein Folbp1 are defective in early embryonic development. Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelstein, O.; Mitchell, L.E.; Merriweather, M.Y.; Wicker, N.J.; Zhang, Q.; Lammer, E.J.; Finnell, R.H. Embryonic development of folate binding protein-1 (Folbp1) knockout mice: Effects of the chemical form, dose, and timing of maternal folate supplementation. Dev. Dyn. 2004, 231, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.H.; Fujita, M.; Takaoka, K.; Murakami, Y.; Fujihara, Y.; Kanzawa, N.; Murakami, K.I.; Kajikawa, E.; Takada, Y.; Saito, K.; et al. A GPI processing phospholipase A2, PGAP6, modulates Nodal signaling in embryos by shedding CRIPTO. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 215, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, N.M. Glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchored membrane enzymes. Clin. Chim. Acta 1997, 266, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustin, M.L.; Selvaraj, P.; Mattaliano, R.J.; Springer, T.A. Anchoring mechanisms for LFA-3 cell adhesion glycoprotein at membrane surface. Nature 1987, 329, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, S.K.; Cunningham, B.A.; Edelman, G.M.; Rodriguez-Boulan, E. Targeting of transmembrane and GPI-anchored forms of N-CAM to opposite domains of a polarized epithelial cell. Nature 1991, 353, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davitz, M.A.; Low, M.G.; Nussenzweig, V. Release of decay-accelerating factor (DAF) from the cell membrane by phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PIPLC). Selective modification of a complement regulatory protein. J. Exp. Med. 1986, 163, 1150–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, A.; Simmons, D.L.; Hale, G.; Harrison, R.A.; Tighe, H.; Lachmann, P.J.; Waldmann, H. CD59, an LY-6-like protein expressed in human lymphoid cells, regulates the action of the complement membrane attack complex on homologous cells. J. Exp. Med. 1989, 170, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haziot, A.; Chen, S.; Ferrero, E.; Low, M.G.; Silber, R.; Goyert, S.M. The monocyte differentiation antigen, CD14, is anchored to the cell membrane by a phosphatidylinositol linkage. J. Immunol. 1988, 141, 547–552. [Google Scholar]

- Ravetch, J.V.; Perussia, B. Alternative membrane forms of Fc gamma RIII(CD16) on human natural killer cells and neutrophils. Cell type-specific expression of two genes that differ in single nucleotide substitutions. J. Exp. Med. 1989, 170, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.S.; Gullapalli, S.; Antony, A.C. Evidence that the hydrophobicity of isolated, in situ, and de novo-synthesized native human placental folate receptors is a function of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchoring to membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 4119–4127. [Google Scholar]

- Paulick, M.G.; Bertozzi, C.R. The glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor: A complex membrane-anchoring structure for proteins. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 6991–7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Kadurin, I.; Alvarez-Laviada, A.; Douglas, L.; Nieto-Rostro, M.; Bauer, C.S.; Pratt, W.S.; Dolphin, A.C. The alpha2delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels form GPI-anchored proteins, a posttranslational modification essential for function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1654–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, I.H.; Biasini, E.; Harris, D.A. Ion channels induced by the prion protein: Mediators of neurotoxicity. Prion 2012, 6, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miwa, J.M.; Ibanez-Tallon, I.; Crabtree, G.W.; Sánchez, R.; Sali, A.; Role, L.W.; Heintz, N. lynx1, an endogenous toxin-like modulator of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mammalian CNS. Neuron 1999, 23, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendo, F.; Araki, Y. Regulation of leukocyte adherence and migration by glycosylphosphatidyl-inositol-anchored proteins. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1999, 66, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingwood, D.; Simons, K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 2010, 327, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; London, E. Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1998, 14, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Toomre, D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.J.; Siu, C.H. Reciprocal raft-receptor interactions and the assembly of adhesion complexes. Bioessays 2002, 24, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.G.; Fujiwara, T.K.; Sanematsu, F.; Iino, R.; Edidin, M.; Kusumi, A. GPI-anchored receptor clusters transiently recruit Lyn and G alpha for temporary cluster immobilization and Lyn activation: Single-molecule tracking study 1. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 177, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, B.P.; van den Berg, C.W.; Davies, E.V.; Hallett, M.B.; Horejsi, V. Cross-linking of CD59 and of other glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored molecules on neutrophils triggers cell activation via tyrosine kinase. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993, 23, 2841–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, T.; Simons, K. Clusters of glycolipid and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in lymphoid cells: Accumulation of actin regulated by local tyrosine phosphorylation. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999, 29, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitrin, R.G.; Pan, P.M.; Harper, H.A.; Blackwood, R.A.; Todd, R.F., 3rd. Urokinase receptor (CD87) aggregation triggers phosphoinositide hydrolysis and intracellular calcium mobilization in mononuclear phagocytes. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 6193–6200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoshitake, H.; Takeda, Y.; Nitto, T.; Sendo, F. Cross-linking of GPI-80, a possible regulatory molecule of cell adhesion, induces up-regulation of CD11b/CD18 expression on neutrophil surfaces and shedding of L-selectin. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002, 71, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyagawa-Yamaguchi, A.; Kotani, N.; Honke, K. Each GPI-anchored protein species forms a specific lipid raft depending on its GPI attachment signal. Glycoconj. J. 2015, 32, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durieux, J.J.; Vita, N.; Popescu, O.; Guette, F.; Calzada-Wack, J.; Munker, R.; Schmidt, R.E.; Lupker, J.; Ferrara, P.; Ziegler-Heitbrock, H.W.; et al. The two soluble forms of the lipopolysaccharide receptor, CD14: Characterization and release by normal human monocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994, 24, 2006–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huizinga, T.W.; de Haas, M.; Kleijer, M.; Nuijens, J.H.; Roos, D.; von dem Borne, A.E. Soluble Fc gamma receptor III in human plasma originates from release by neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 1990, 86, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medof, M.E.; Walter, E.I.; Rutgers, J.L.; Knowles, D.M.; Nussenzweig, V. Identification of the complement decay-accelerating factor (DAF) on epithelium and glandular cells and in body fluids. J. Exp. Med. 1987, 165, 848–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploug, M.; Eriksen, J.; Plesner, T.; Hansen, N.E.; Dano, K. A soluble form of the glycolipid-anchored receptor for urokinase-type plasminogen activator is secreted from peripheral blood leukocytes from patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992, 208, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitto, T.; Araki, Y.; Takeda, Y.; Sendo, F. Pharmacological analysis for mechanisms of GPI-80 release from tumour necrosis factor-alpha-stimulated human neutrophils. Br. J. Pharm. 2002, 137, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosaki, A.; Hasegawa, K.; Kato, T.; Abe, K.; Hanaoka, T.; Miyara, A.; O’Shannessy, D.J.; Somers, E.B.; Yasuda, M.; Sekino, T.; et al. Serum folate receptor alpha as a biomarker for ovarian cancer: Implications for diagnosis, prognosis and predicting its local tumor expression. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 1994–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xie, L.; He, L.; Fan, Z.; Xu, J.; Xu, K.; Zhu, L.; Ma, G.; Du, M.; Chu, H.; et al. Plasma Mesothelin as a Novel Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker in Colorectal Cancer. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.L.; Fan, J.H.; Wu, J. Prognostic Role of Circulating Soluble uPAR in Various Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Lab. 2017, 63, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, N.; Takano, A.; Yasui, W.; Inai, K.; Nishimura, H.; Ito, H.; Miyagi, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Fujita, M.; Hosokawa, M.; et al. Cancer-testis antigen lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus K is a serologic biomarker and a therapeutic target for lung and esophageal carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 11601–11611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshitake, H.; Nitto, T.; Ohta, N.; Fukase, S.; Aoyagi, M.; Sendo, F.; Araki, Y. Elevation of the soluble form GPI-80, a β2 integrin-associated glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchored protein, in the serum of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Allergol. Int. 2005, 54, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Lu, C.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J. CD109 is a novel marker for squamous cell/adenosquamous carcinomas of the gallbladder. Diagn. Pathol. 2015, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaret, J.; Venet, F.; Plassais, J.; Cazalis, M.A.; Vallin, H.; Friggeri, A.; Lepape, A.; Rimmele, T.; Textoris, J.; Monneret, G. Identification of CD177 as the most dysregulated parameter in a microarray study of purified neutrophils from septic shock patients. Immunol. Lett. 2016, 178, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, H. Semaphorin 7A as a potential immune regulator and promising therapeutic target in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshitake, H.; Yanagida, M.; Maruyama, M.; Takamori, K.; Hasegawa, A.; Araki, Y. Molecular characterization and expression of dipeptidase 3, a testis-specific membrane-bound dipeptidase: Complex formation with TEX101, a germ-cell-specific antigen in the mouse testis. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011, 90, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G.M.; Lo, J.C.; Nixon, B.; Jamsai, D.; O’Connor, A.E.; Rijal, S.; Sanchez-Partida, L.G.; Hearn, M.T.; Bianco, D.M.; O’Bryan, M.K. Glioma pathogenesis-related 1-like 1 is testis enriched, dynamically modified, and redistributed during male germ cell maturation and has a potential role in sperm-oocyte binding. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 2331–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Kimmel, L.H.; Myles, D.G.; Primakoff, P. Molecular cloning of the human and monkey sperm surface protein PH-20. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 10071–10075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Baba, D.; Kimura, M.; Yamashita, M.; Kashiwabara, S.; Baba, T. Identification of a hyaluronidase, Hyal5, involved in penetration of mouse sperm through cumulus mass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18028–18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, M.; Yoshitake, H.; Tsukamoto, H.; Takamori, K.; Araki, Y. Molecular expression of Ly6k, a putative glycosylphosphatidyl-inositol-anchored membrane protein on the mouse testicular germ cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 402, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peoc’h, K.; Serres, C.; Frobert, Y.; Martin, C.; Lehmann, S.; Chasseigneaux, S.; Sazdovitch, V.; Grassi, J.; Jouannet, P.; Launay, J.M.; et al. The human “prion-like” protein Doppel is expressed in both Sertoli cells and spermatozoa. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 43071–43078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takano, N.; Matsui, H.; Takahashi, T. TESSP-1: A novel serine protease gene expressed in the spermatogonia and spermatocytes of adult mouse testes. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2005, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, J.; Wolkowicz, M.J.; Digilio, L.C.; Klotz, K.L.; Jayes, F.L.; Diekman, A.B.; Westbrook, V.A.; Farris, E.M.; Hao, Z.; Coonrod, S.A.; et al. SAMP14, a novel, acrosomal membrane-associated, glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored member of the Ly-6/urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor superfamily with a role in sperm-egg interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 30506–30515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunnicutt, G.R.; Primakoff, P.; Myles, D.G. Sperm surface protein PH-20 is bifunctional: One activity is a hyaluronidase and a second, distinct activity is required in secondary sperm-zona binding. Biol. Reprod. 1996, 55, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galat, A. The three-fingered protein domain of the human genome. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 3481–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichok, Y.; Navarro, B.; Clapham, D.E. Whole-cell patch-clamp measurements of spermatozoa reveal an alkaline-activated Ca2+ channel. Nature 2006, 439, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Moran, M.M.; Navarro, B.; Chong, J.A.; Krapivinsky, G.; Krapivinsky, L.; Kirichok, Y.; Ramsey, I.S.; Quill, T.A.; Clapham, D.E. All four CatSper ion channel proteins are required for male fertility and sperm cell hyperactivated motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.H.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.L.; Ling, Y.; Li, Z.L.; Sun, L.B. The Catsper channel and its roles in male fertility: A systematic review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2017, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masutani, M.; Sakurai, S.; Shimizu, T.; Ohto, U. Crystal structure of TEX101, a glycoprotein essential for male fertility, reveals the presence of tandemly arranged Ly6/uPAR domains. FEBS Lett. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Satue, M.; Lavoie, E.G.; Fausther, M.; Lecka, J.; Aliagas, E.; Kukulski, F.; Sevigny, J. High expression and activity of ecto-5’-nucleotidase/CD73 in the male murine reproductive tract. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 133, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egbunike, G.N. Changes in acetylcholinesterase activity of mammalian spermatozoa during maturation. Int. J. Androl. 1980, 3, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, J.; Damjanov, I.; Lange, P.H.; Harris, H. Immunohistochemical localization of placental-like alkaline phosphatase in testis and germ-cell tumors using monoclonal antibodies. Am. J. Pathol. 1983, 111, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koshida, K.; Stigbrand, T.; Hisazumi, H.; Wahren, B. Electrophoretic heterogeneity of alkaline phosphatase isozymes in seminoma and normal testis. Tumour Biol. 1989, 10, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mii, S.; Murakumo, Y.; Asai, N.; Jijiwa, M.; Hagiwara, S.; Kato, T.; Asai, M.; Enomoto, A.; Ushida, K.; Sobue, S.; et al. Epidermal hyperplasia and appendage abnormalities in mice lacking CD109. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K.L.; Holmes, C.H. Differential expression of complement regulatory proteins decay-accelerating factor (CD55), membrane cofactor protein (CD46) and CD59 during human spermatogenesis. Immunology 1994, 81, 452–461. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, G.M.; Shi, Z.Z.; Cuevas, A.A.; Lieberman, M.W. Identification of two additional members of the membrane-bound dipeptidase family. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1313–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoff, M.S.; Middendorff, R.; Koeva, Y.; Pusch, W.; Jezek, D.; Muller, D. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and its receptors GFRalpha-1 and GFRalpha-2 in the human testis. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 2001, 106 (Suppl. S2), 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Thway, K.; Selfe, J.; Shipley, J. Immunohistochemical detection of glypican-5 in paraffin-embedded material: An optimized method for a novel research antibody. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2012, 20, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.E.; Lindegaard, M.L.; Friis-Hansen, L.; Almstrup, K.; Leffers, H.; Nielsen, L.B.; Rajpert-De Meyts, E. Lipoprotein lipase and endothelial lipase in human testis and in germ cell neoplasms. Int. J. Androl. 2010, 33, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bragt, M.P.; Ciliberti, N.; Stanford, W.L.; de Rooij, D.G.; van Pelt, A.M. LY6A/E (SCA-1) expression in the mouse testis. Biol. Reprod. 2005, 73, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Trivedi, R.N.; Naz, R.K. Testis-specific antigen (TSA-1) is expressed in murine sperm and its antibodies inhibit fertilization. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2002, 47, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lang, Q.; Li, J.; Xie, F.; Wan, B.; Yu, L. Identification and characterization of human LYPD6, a new member of the Ly-6 superfamily. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2010, 37, 2055–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, T.K.; Pastan, I. Mesothelin is not required for normal mouse development or reproduction. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 20, 2902–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, C.; Liu, W.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Freeman, G.J.; Schneyer, A.; Lin, H.Y.; Xia, Y. Repulsive Guidance Molecule b (RGMb) Is Dispensable for Normal Gonadal Function in Mice. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 94, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneda, R.; Kimura, A.P. A testis-specific serine protease, Prss41/Tessp-1, is necessary for the progression of meiosis during murine in vitro spermatogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 441, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepekoy, F.; Ozturk, S.; Sozen, B.; Ozay, R.S.; Akkoyunlu, G.; Demir, N. CD90 and CD105 expression in the mouse ovary and testis at different stages of postnatal development. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 15, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spierings, D.C.; de Vries, E.G.; Vellenga, E.; van den Heuvel, F.A.; Koornstra, J.J.; Wesseling, J.; Hollema, H.; de Jong, S. Tissue distribution of the death ligand TRAIL and its receptors. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2004, 52, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyte, J.; Doolittle, R.F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982, 157, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, E.T.; Kamitani, T.; Chang, H.M. Biosynthesis and processing of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor in mammalian cells. Semin. Immunol. 1994, 6, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulsiani, D.R.; Yoshida-Komiya, H.; Araki, Y. Mammalian fertilization: A carbohydrate-mediated event. Biol. Reprod. 1997, 57, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonezawa, N. Posttranslational modifications of zona pellucida proteins. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 759, 111–140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, E.; Wright, G.J. Sperm Meets Egg: The Genetics of Mammalian Fertilization. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2016, 50, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.C.; Wang, J.H.; Wang, X.X.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, C.L.; Hao, C.F.; Ma, W.Z.; Deng, S.L.; Liu, Y.X. Effects of sperm proteins on fertilization in the female reproductive tract. Front. Biosci. 2019, 24, 735–749. [Google Scholar]

- Helenius, A.; Aebi, M. Intracellular functions of N-linked glycans. Science 2001, 291, 2364–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitake, H.; Shirai, Y.; Mochizuki, Y.; Iwanari, H.; Tsubamoto, H.; Koyama, K.; Takamori, K.; Ogawa, H.; Hasegawa, A.; Kodama, T.; et al. Molecular diversity of TEX101, a marker glycoprotein for germ cells monitored with monoclonal antibodies: Variety of the molecular characteristics according to subcellular localization within the mouse testis. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2008, 79, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, Y.; Yoshitake, H.; Maruyama, M.; Takamori, K.; Ogawa, H.; Hasegawa, A.; Araki, Y. Distribution of molecular epitope for Ts4, an anti-sperm auto-monoclonal antibody in the fertilization process. J. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 55, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshitake, H.; Hashii, N.; Kawasaki, N.; Endo, S.; Takamori, K.; Hasegawa, A.; Fujiwara, H.; Araki, Y. Chemical Characterization of N-Linked Oligosaccharide As the Antigen Epitope Recognized by an Anti-Sperm Auto-Monoclonal Antibody, Ts4. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, T.; Mishima, T.; Mori, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Takizawa, T.; Goto, T.; Suzuki, M.; Araki, Y.; Matsubara, S.; Takizawa, T. TEX101 is shed from the surface of sperm located in the caput epididymidis of the mouse. Zygote 2005, 13, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda-Sakurai, R.; Yoshitake, H.; Miura, Y.; Kazuno, S.; Ueno, T.; Hasegawa, A.; Yamatoya, K.; Takamori, K.; Itakura, A.; Fujiwara, H.; et al. NUP62: The target of an anti-sperm auto-monoclonal antibody during testicular development. Reproduction 2019, 158, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitake, H.; Oda, R.; Yanagida, M.; Kawasaki, Y.; Sakuraba, M.; Takamori, K.; Hasegawa, A.; Fujiwara, H.; Araki, Y. Identification of an anti-sperm auto-monoclonal antibody (Ts4)-recognized molecule in the mouse sperm acrosomal region and its inhibitory effect on fertilization in vitro. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016, 115, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebbaa, A.; Yamamoto, H.; Saito, T.; Meuillet, E.; Kim, P.; Kersey, D.S.; Bremer, E.G.; Taniguchi, N.; Moskal, J.R. Gene transfection-mediated overexpression of beta1,4-N-acetylglucosamine bisecting oligosaccharides in glioma cell line U373 MG inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 9275–9279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitada, T.; Miyoshi, E.; Noda, K.; Higashiyama, S.; Ihara, H.; Matsuura, N.; Hayashi, N.; Kawata, S.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Taniguchi, N. The addition of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine residues to E-cadherin down-regulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of beta-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaji, T.; Gu, J.; Nishiuchi, R.; Zhao, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Miyoshi, E.; Honke, K.; Sekiguchi, K.; Taniguchi, N. Introduction of bisecting GlcNAc into integrin alpha5beta1 reduces ligand binding and down-regulates cell adhesion and cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 19747–19754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawson, T.; Nash, P. Assembly of cell regulatory systems through protein interaction domains. Science 2003, 300, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seet, B.T.; Dikic, I.; Zhou, M.M.; Pawson, T. Reading protein modifications with interaction domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsume, T.; Yamauchi, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Shinkawa, T.; Yanagida, M.; Takahashi, N.; Isobe, T. A direct nanoflow liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry system for interaction proteomics. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 4725–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, V.; Moss, S.E. Annexins: From structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 331–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Bilinska, B.; Mruk, D.D. Annexin A2 is critical for blood-testis barrier integrity and spermatid disengagement in the mammalian testis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.A.; Scheller, R.H. SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, G.M.; Shi, Z.Z.; Cuevas, A.A.; Guo, Q.; Matzuk, M.M.; Lieberman, M.W. Leukotriene D4 and cystinyl-bis-glycine metabolism in membrane-bound dipeptidase-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 4859–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Khan, R.; Wahab, F.; Hussain, H.M.J.; Ali, A.; Ma, H.; Jiang, H.; Xu, J.; Zaman, Q.; Khan, M.; et al. The testis-specifically expressed Dpep3 is not essential for male fertility in mice. Gene 2019, 711, 143925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, H.; Zebisch, M.; Sträter, N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal 2012, 8, 437–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resta, R.; Hooker, S.W.; Hansen, K.R.; Laurent, A.B.; Park, J.L.; Blackburn, M.R.; Knudsen, T.B.; Thompson, L.F. Murine ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73): cDNA cloning and tissue distribution. Gene 1993, 133, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioli, L.; Pacher, P.; Vizi, E.S.; Haskó, G. CD39 and CD73 in immunity and inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, J.; Smyth, M.J. Extracellular adenosine triphosphate and adenosine in cancer. Oncogene 2010, 29, 5346–5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, R.; Muro, Y.; Isotani, A.; Tokuhiro, K.; Takumi, K.; Adham, I.; Ikawa, M.; Okabe, M. Disruption of ADAM3 impairs the migration of sperm into oviduct in mouse. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 81, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikawa, M.; Wada, I.; Kominami, K.; Watanabe, D.; Toshimori, K.; Nishimune, Y.; Okabe, M. The putative chaperone calmegin is required for sperm fertility. Nature 1997, 387, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikawa, M.; Tokuhiro, K.; Yamaguchi, R.; Benham, A.M.; Tamura, T.; Wada, I.; Satouh, Y.; Inoue, N.; Okabe, M. Calsperin is a testis-specific chaperone required for sperm fertility. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 5639–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuhiro, K.; Ikawa, M.; Benham, A.M.; Okabe, M. Protein disulfide isomerase homolog PDILT is required for quality control of sperm membrane protein ADAM3 and male fertility [corrected]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 3850–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, H.; Kim, E.; Nakanishi, T.; Baba, T. Possible function of the ADAM1a/ADAM2 Fertilin complex in the appearance of ADAM3 on the sperm surface. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34957–34962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, S.; Yoshitake, H.; Tsukamoto, H.; Matsuura, H.; Kato, K.; Sakuraba, M.; Takamori, K.; Fujiwara, H.; Takeda, S.; Araki, Y. TEX101, a glycoprotein essential for sperm fertility, is required for stable expression of Ly6k on testicular germ cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujihara, Y.; Okabe, M.; Ikawa, M. GPI-anchored protein complex, LY6K/TEX101, is required for sperm migration into the oviduct and male fertility in mice. Biol. Reprod. 2014, 90, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, M. The cell biology of mammalian fertilization. Development 2013, 140, 4471–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Protein Name | Putative Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 5′-nucleotidase (CD73) | Enzyme | [86] |

| Acetylcholinesterase | Enzyme | [87] |

| Alkaline phosphatase, placental-like | Enzyme | [88] |

| Alkaline phosphatase, tissue-nonspecific isozyme | Enzyme | [89] |

| CD109 | Receptor | [90] |

| CD59 | Complement regulator | [91] |

| Complement decay-accelerating factor (CD55) | Complement regulator | [91] |

| Dipeptidase 2 (DPEP2) | Enzyme | [92] |

| Dipeptidase 3 (DPEP3) | Enzyme | [72] |

| GDNF family receptor alpha-1 | Receptor | [93] |

| GDNF family receptor alpha-2 | Receptor | [93] |

| Glypican-5 | Receptor | [94] |

| GLIPR1-like protein 1 | Others | [73] |

| Hyaluronidase PH-20 | Enzyme | [75] |

| Hyaluronidase-5 | Enzyme | [75] |

| Lipoprotein lipase | Enzyme | [95] |

| Lymphocyte antigen 6A-2/6E-1 (Ly6A/E) | Others | [96] |

| Lymphocyte antigen 6E (Ly6E) | Receptor | [97] |

| Lymphocyte antigen 6K (Ly6K) | Others | [12] |

| Ly6/PLAUR domain-containing protein 6 * | Receptor | [98] |

| Mesothelin * | Others | [99] |

| Prion-like protein doppel | Receptor | [77] |

| RGM domain family member B | Receptor | [100] |

| Serine protease 41 | Enzyme | [101] |

| Sperm acrosome membrane-associated protein 4 | Enzyme | [79] |

| Testis-expressed protein 101 (TEX101) | Others | [9] |

| Testisin | Enzyme | [25] |

| Thy-1 membrane glycoprotein | Others | [102] |

| TNF receptor superfamily membrane 10C | Receptor | [103] |

| Species | Amino Acid # | |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse | mgacriqyvl liflliasrw tlvqntycqv sqtlsleddp grtfnwtska | 50 |

| Rat | mgacriqyil lvflliashw tlvqniycev srtlslednp sgtfnwtska | 50 |

| Human | mgtpriqhll illvlgasll tsglelycqk glsmtveadp anmfnwttee | 50 |

| Bovine | mgachfqgll llflvgaptl imaqklfcqk gtfmgiqeda tnmfnwtsek | 50 |

| Mouse | -eqcnpgelcq etvllikadg trtvvlasks cvsqggeavt fiqytappgl | 100 |

| Rat | -ekcnpgefcq etvllikaeg tktailasks cvpqgaetmt fvqytappgl | 100 |

| Human | vetcdkgalcq etiliikag- tetailatkg cipegeeait ivqhssppgl | 100 |

| Bovine | veacdngtlcq etilliktag tktailatks csldgtpait fiqhtaapsl | 100 |

| Mouse | vaisysnycn dslcnnkdsl asvwrvpett a-tsnmsgtr- hcptcvalgsc- | 150 |

| Rat | vaisysnycn dslcnnrnnl asilqapept a-tsnmsgar- hcptclalepc- | 150 |

| Human | ivtsysnyce dsfcndkdsl sqfwefsett astvst--tl- hcptcvalgtcf | 150 |

| Bovine | aaisysnyce dpfcnnregl ydiwniqete eetkgt—tsl- hcptclalgsc | 150 |

| Mouse | ssapsmpcan gttqcyqgrl efsgggmdat vqvkgcttti gcrlmamids | 200 |

| Rat | ssapsmpcan gttqcyhgki elsgggmdsv vhvkgcttai gcrlmakmes | 200 |

| Human | sapslp-cpn gttrcyqgkl eitgggiess vevkgctami gcrlmsgila | 200 |

| Bovine | lnapsvacpn ntdrcyqgkl qvsegnvnsl leikgctsii gcklmsgvfk | 200 |

| Mouse | -vgpmtvketc syqsflqprk aeigasqmpt slwvlellfp- llllplth---fp | 250 |

| Rat | -vgpmtvketc syqsflhprm aeigaswmpt slwvlelllp- alslpliy---fp | 250 |

| Human | -vgpmfvreac phqlltqprk tengatclpi pvwglqlllp- ll-lpsfih--fp | 249 |

| Bovine | kigplwvketc psmsist-rk idngatwlht svwklklllm- llllilggsasgp | 253 |

| Species | Amino acid # |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoshitake, H.; Araki, Y. Role of the Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Protein TEX101 and Its Related Molecules in Spermatogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186628

Yoshitake H, Araki Y. Role of the Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Protein TEX101 and Its Related Molecules in Spermatogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(18):6628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186628

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshitake, Hiroshi, and Yoshihiko Araki. 2020. "Role of the Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Protein TEX101 and Its Related Molecules in Spermatogenesis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 18: 6628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186628

APA StyleYoshitake, H., & Araki, Y. (2020). Role of the Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Protein TEX101 and Its Related Molecules in Spermatogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(18), 6628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186628