Abstract

USH2A is a common causal gene of retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a progressive blinding disease due to retinal degeneration. Genetic alterations in USH2A can lead to two types of RP, non-syndromic and syndromic RP, which is called Usher syndrome, with impairments of vision and hearing. The complexity of the genotype–phenotype correlation in USH2A-associated RP (USH2A-RP) has been reported. Genetic and clinical characterization of USH2A-RP has not been performed in Japanese patients. In this study, genetic analyses were performed using targeted panel sequencing in 525 Japanese RP patients. Pathogenic variants of USH2A were identified in 36 of 525 (6.9%) patients and genetic features of USH2A-RP were characterized. Among 36 patients with USH2A-RP, 11 patients had syndromic RP with congenital hearing problems. Amino acid changes due to USH2A alterations were similarly located throughout entire regions of the USH2A protein structure in non-syndromic and syndromic RP cases. Notably, truncating variants were detected in all syndromic patients with a more severe retinal phenotype as compared to non-syndromic RP cases. Taken together, truncating variants could contribute to more serious functional and tissue damages in Japanese patients, suggesting important roles for truncating mutations in the pathogenesis of syndromic USH2A-RP.

1. Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the most common type of inherited retinal degenerative disease (IRD) and is clinically and genetically heterogeneous. Symptoms of this disease include night blindness, visual field constriction and a decline in vision. More than 70 and 270 causal genes in RP and in IRD, respectively, have been reported by the University of Texas Houston Health Science Center, Houston, TX, USA., (https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/). Although there are racial differences in causal genes, USH2A is one of the most frequent genes in Caucasian, Japanese and other populations [1,2]. Alterations in USH2A are responsible for Usher syndrome, which is the most common syndromic RP with sensorineural hearing loss [3]. Usher syndrome is classified into three types, type I, II and III, and causal genes of type II include USH2A, ADGRV1, and WHRN (DFNB31) [4]. USH2A is responsible for about 80–90% of Usher syndrome type II and USH2A-causing Usher syndrome is called Usher syndrome type IIa, which is an autosomal recessive disease [5,6,7]. In addition, non-syndromic RP and non-syndromic hearing loss can be also caused by USH2A variants [8,9,10]. Alterations in USH2A lead to a wide range of phenotypes and severity of the diseases.

USH2A is located on chromosome 1q41 in the human genome and is approximately 790 kb of genomic DNA containing 72 exons [11]. This gene codes for the transmembrane protein USH2A (Usherin) which is expressed in the junction between the inner and outer segments, the cilia region in the photoreceptor cells [12,13,14]. USH2A plays important roles in the development and homeostasis of the inner ear and the retina [15,16]. Because this protein belongs to cilial proteins, USH2A-associated diseases are categorized to ciliopathies [17,18]. In previous studies, USH2A is a frequent causal gene in Japanese RP patients as well as Caucasian RP patients, yet the mutation spectrum is different among different ethnic groups [19,20]. Genotype–phenotype correlation in USH2A has been reported where truncating variants are associated with more severe visual and hearing impairments [9,21,22], and similar trends have also been reported in Asians [23,24]. In contrast, there are studies reporting that the differences in phenotypes are not clear in syndromic and non-syndromic or truncating variants and non-truncating variants [25,26]. Furthermore, there are few reports in Japanese patients examining the genotype–phenotype correlation in USH2A-RP.

In this study, we investigated the genetic and clinical characteristics focusing on the relationship between gene alterations and syndromic or non-syndromic USH2A-RP in Japanese patients. This study could provide additional evidence of race-specific genetic features in IRD and emphasize important roles of truncating variants, which lead to remnant protein functions for the pathogenesis of USH2A-RP.

2. Results

2.1. Syndromic and Non-Syndromic USH2A-RP

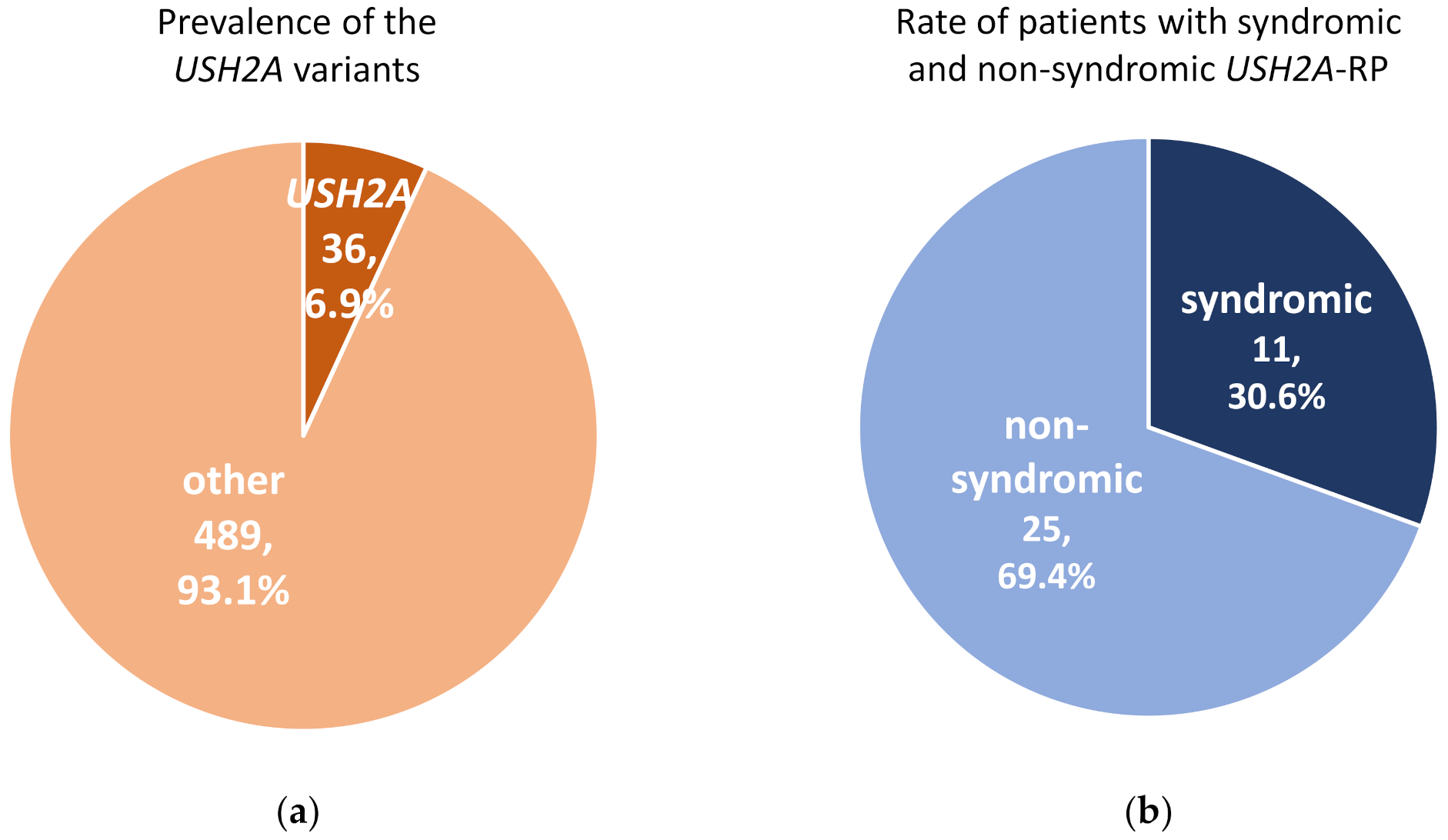

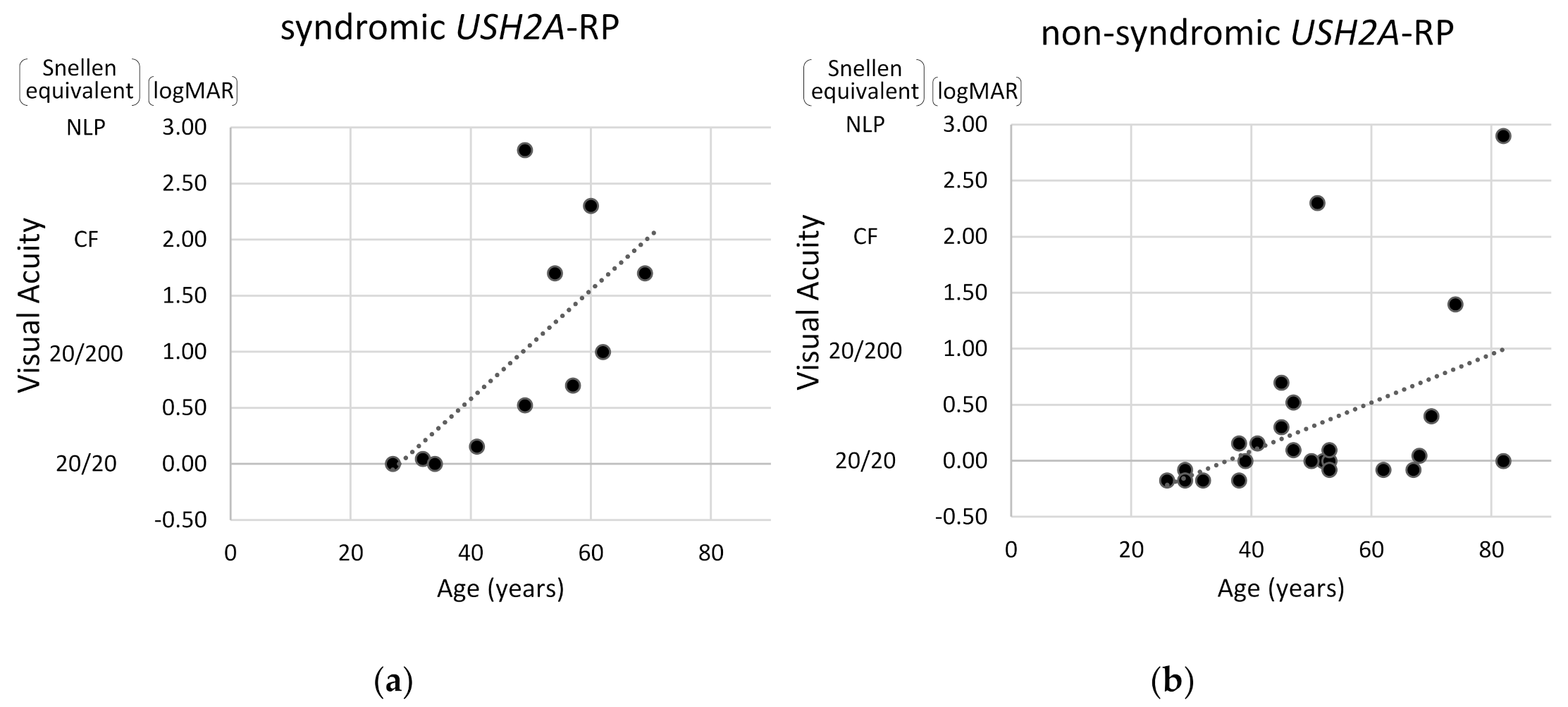

A total of 525 RP patients underwent genetic analysis and pathogenic variants were identified in 287 (54.7%) RP patients in this cohort. In these 525 RP patients, 36 (6.9%) cases carried USH2A variants which could explain their symptoms (Figure 1a). Among 36 patients with USH2A-RP, 11 (30.6%) patients were syndromic RP with congenital hearing loss (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of pathogenic variants in USH2A and rate of syndromic and non-syndromic USH2A-retinisis pigmentosa (RP) patients. (a) Pathogenic USH2A variants were detected in 36 of 525 RP cases. (b) There were 11 syndromic and 25 non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients in this study.

The genetic characteristics of syndromic and non-syndromic RP patients are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. Among both groups, no significant differences were observed regarding age, gender, and consanguineous marriage. All 36 USH2A-RP cases showed an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, but affected family members were found at a higher rate in syndromic USH2A-RP cases than non-syndromic USH2A-RP cases, although statistical differences were not detected (p = 0.25).

Table 1.

USH2A variants detected in RP patients in this study.

Table 2.

Characteristics of syndromic and non-syndromic RP patients.

2.2. Truncating USH2A Variants were More Frequently Detected in Syndromic than Non-Syndromic USH2A-RP Patients

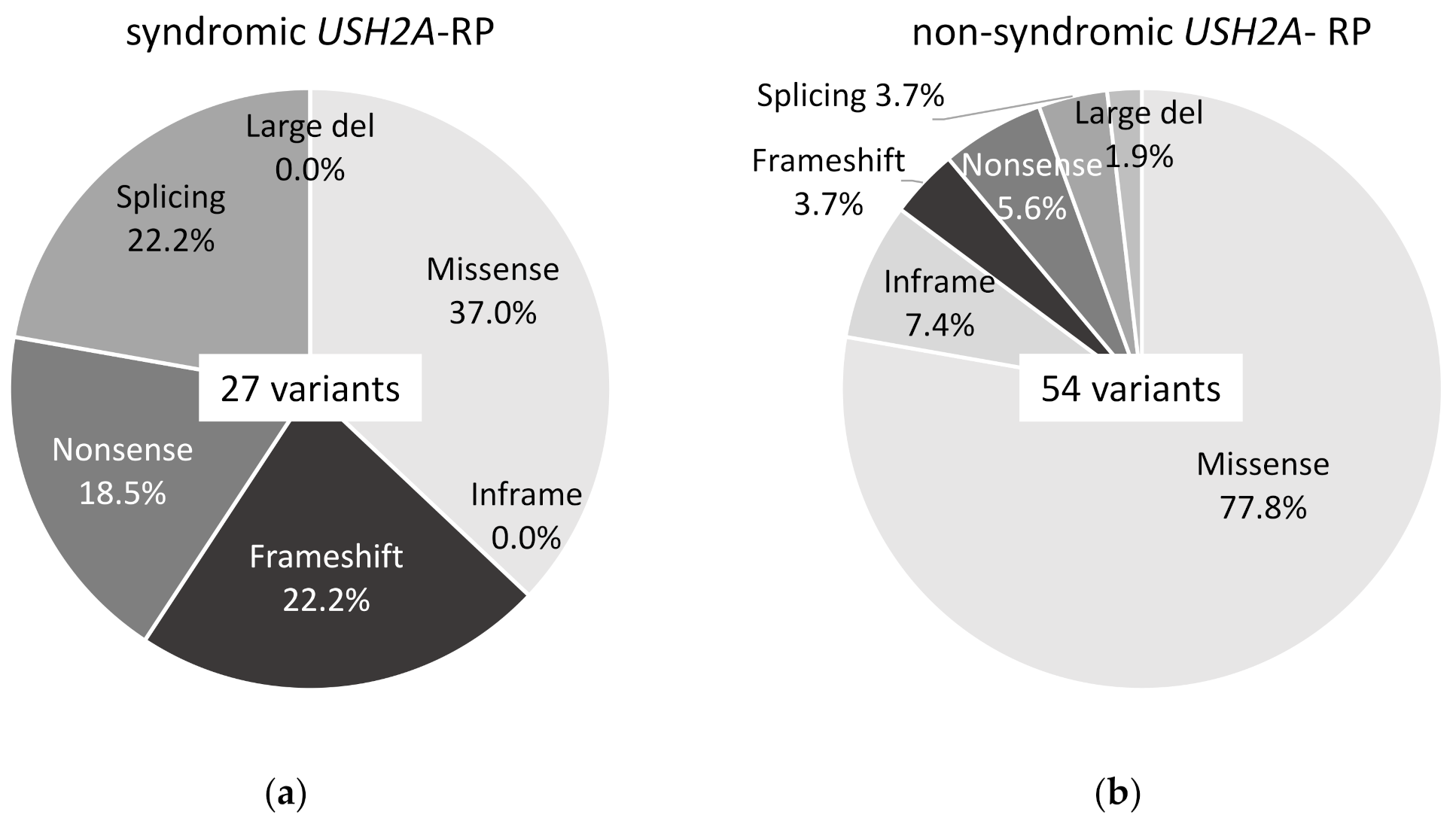

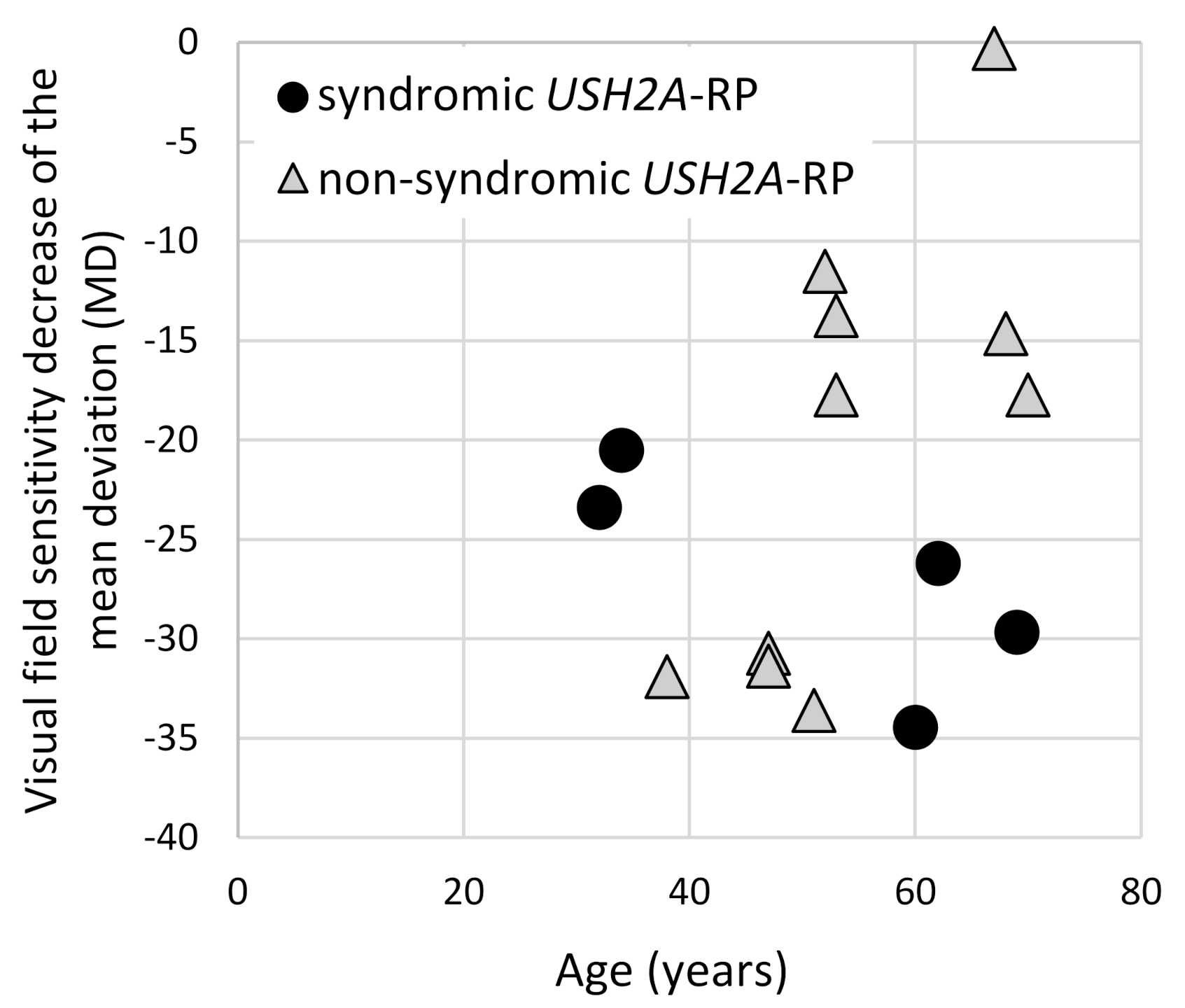

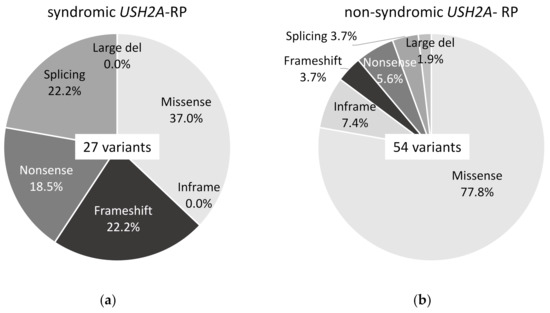

Twenty-seven variants of USH2A were detected in 11 syndromic USH2A-RP patients and 54 variants in 25 non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients, which can explain their symptoms. Ten missense variants (37.0%), 6 frameshift variants (22.2%), 5 nonsense variants (18.5%), and 6 splicing variants (22.2%) were detected in syndromic USH2A-RP patients (Figure 2a). Forty-two missense variants (77.8%), 4 inframe variants (7.4%), 2 frameshift variants (3.7%), 3 nonsense variant (5.6%), 2 splicing variants (3.7%), and 1 large deletion variant (1.9%) were detected in non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Frequency of each type of USH2A variant in this study. (a) Frequency of 6 types of 27 USH2A variants in syndromic USH2A-RP patients (n = 11). (b) Frequency of 6 types of 54 USH2A variants in non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients (n = 25).

Notably, a pattern of missense/missense or truncating/truncating was not observed in syndromic or in non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients, respectively (Table 3). In contrast to the observation that 32.0% (8 of 25) non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients had truncating variants such as nonsense, frameshift, or out of frame exon deletion, all syndromic RP patients (100.0%; 11 of 11) carried at least one truncating variant, which was significantly higher in syndromic RP (p < 0.01) (Table 3). All USH2A-RP patients with two truncating variants (n = 6) had both RP and early onset hearing loss.

Table 3.

Three types of combinations of USH2A variants in this study.

Frequently detected USH2A variants were p.(Cys934Trp) (one syndromic patient and four non-syndromic patients), p.(Gly2752Arg) (five non-syndromic patients), and c.8559-2A>G (four syndromic patients and one non-syndromic patient) (Table 4).

Table 4.

USH2A variants detected in this study.

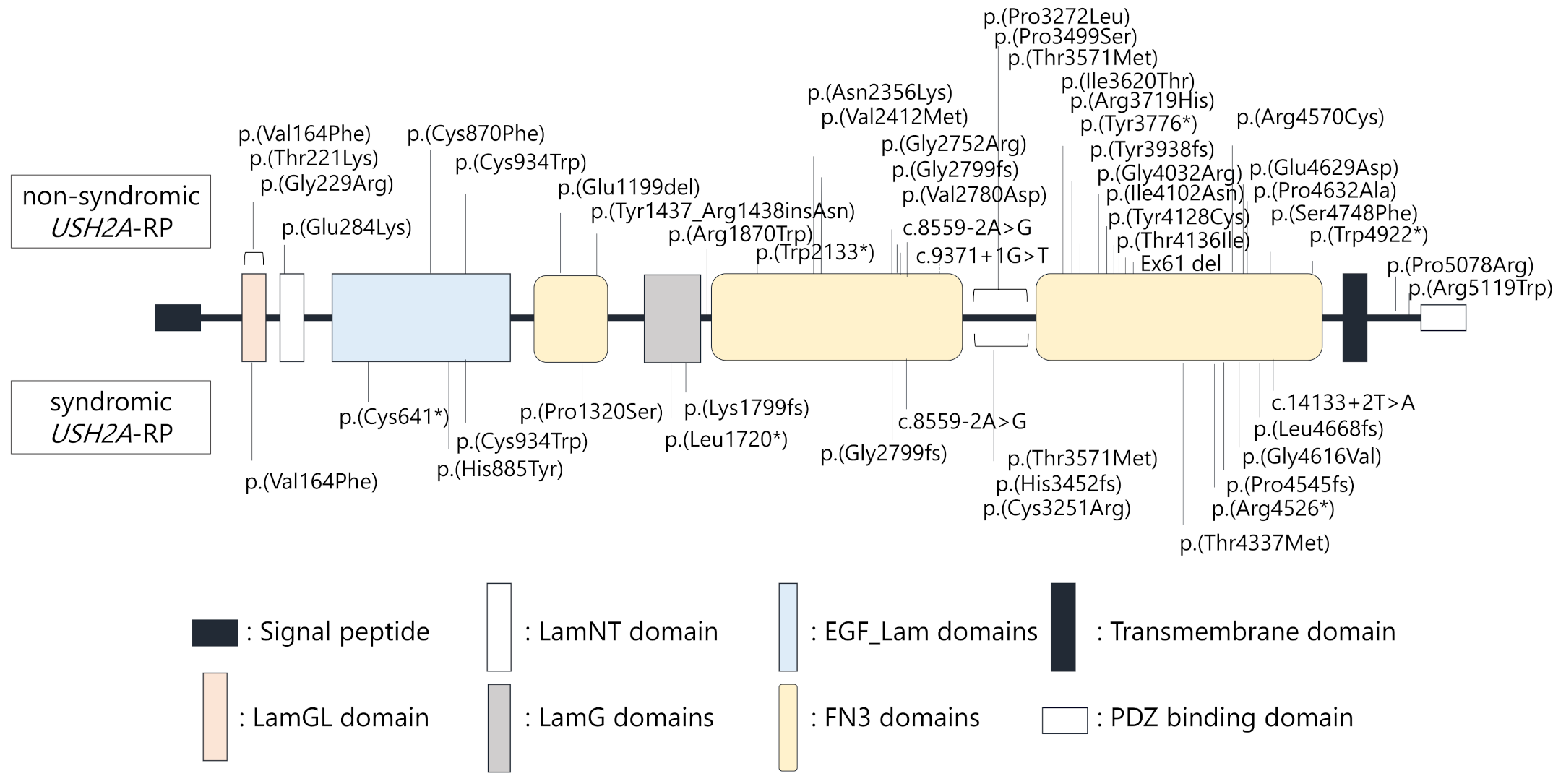

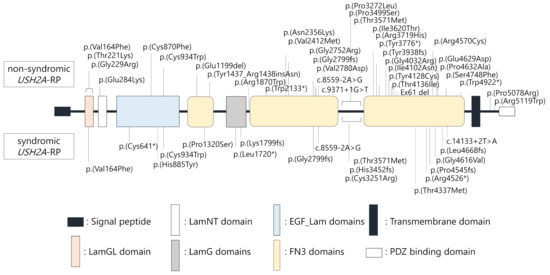

Locations of each variant in the USH2A protein structure were schematically presented (Figure 3). Notably, USH2A variants were similarly found throughout entire regions of the USH2A protein structure in non-syndromic and syndromic USH2A-RP cases, suggesting that localization of variants does not correlate with hearing loss in USH2A-RP.

Figure 3.

Schematic distribution of the USH2A variants identified in this study. Upper variants were detected in non-syndromic patients (n = 25), lower variants were detected in syndromic patients (n = 11).

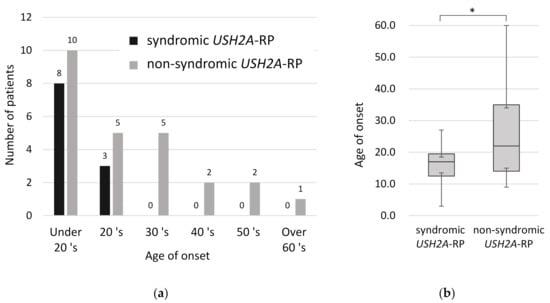

2.3. Earlier Onset of RP in Syndromic Patients than Non-Syndromic USH2A-RP Patients

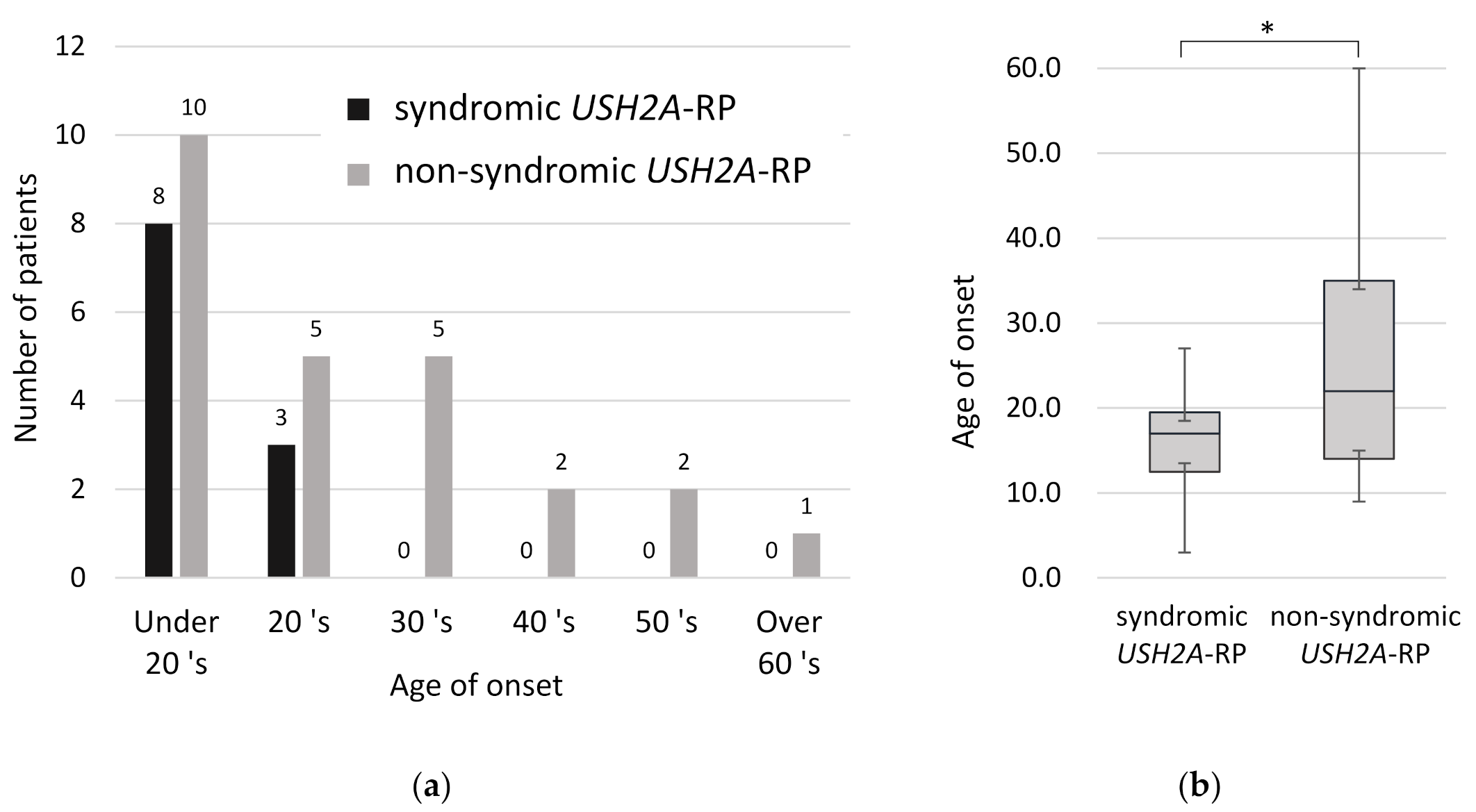

In order to understand clinical features between syndromic and non-syndromic USH2A-RP, age of disease onset was examined. All syndromic RP patients were aware of symptoms related to RP such as night blindness and constriction of visual field by their third decade of life (Figure 4a). Comparing the onset age of RP in 11 syndromic and 25 non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients, syndromic RP patients were aware of symptoms significantly earlier than non-syndromic patients (p < 0.05) (Figure 4b). The mean age of onset was 16.1 and 26.5 years old in syndromic and non- syndromic USH2A-RP patients, respectively.

Figure 4.

Onset age of RP in 11 syndromic and 25 non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients. (a) Distribution of onset age in syndromic and non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients. The vertical line shows the number of patients and the horizontal one shows the onset age of RP. Numeric numbers above each column indicate patients’ numbers. (b) Box plot of onset age in syndromic and non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients. The bottom and top of each box represent the lower and upper quartiles, respectively, and the line inside each box represents the median. The bottom and top bars represent the minimum and maximum value, respectively. p < 0.05 (*).

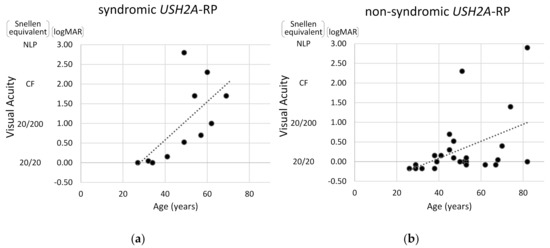

2.4. Visual Acuity and Visual Field Constriction in Syndromic and Non-Syndromic USH2A-RP Patients

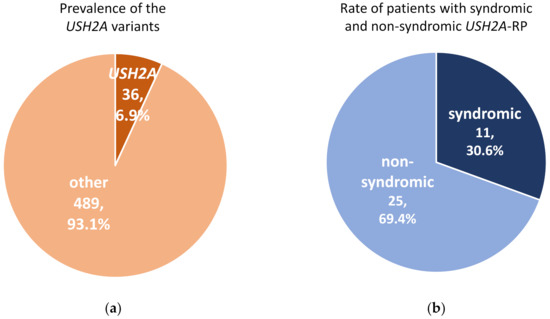

Next, visual acuity and degrees of visual field constriction were compared between syndromic and non-syndromic USH2A-RP cases. As shown in Figure 5, the correlation between age and visual acuity was more pronounced in syndromic USH2A-RP patients than in non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients. These data also indicate that a decline in visual acuity is more rapid in syndromic USH2A-RP cases than non-syndromic USH2A-RP cases.

Figure 5.

Scatter distribution of visual acuity and age in USH2A-RP cases. The vertical line shows visual acuity (Snellen equivalent and logMAR) and the horizontal one shows age of patient. One plot shows one patient and dash lines represent approximate straight lines. Results of 11 syndromic (a) and 25 non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients (b) are respectively presented. NLP: no light perception, CF: counting fingers.

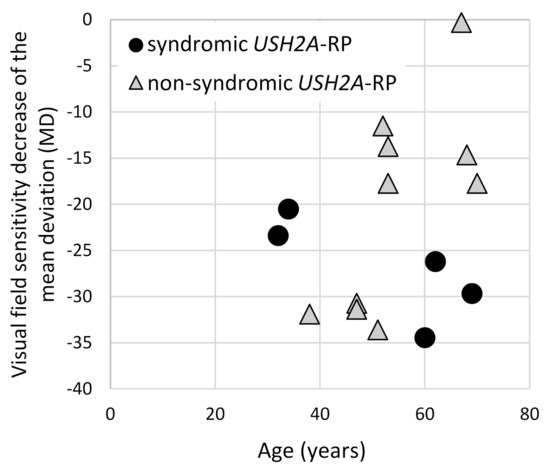

To evaluate the visual field changes, HFA data were obtained from five syndromic and 10 non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients (Figure 6). Lower MD values and a decline in these values were revealed in syndromic USH2A-RP patients, indicating more severe visual field problems. Non-syndromic USH2A-RP cases were divided into two groups, a low MD (lower than −30) group aged in their 40s versus a moderate MD group in their 50s–70s. Because patients with truncating USH2A-variants belong to both groups, one of four in the low-MD group and two of six in the moderate-MD group, a clear contribution of truncating USH2A variants was not observed.

Figure 6.

Correlation of the visual field changes and age of syndromic and non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients. The vertical line shows the mean deviation value (MD) which was obtained from HFA and the horizontal one shows age of patient. One dot represents each patient and round dots and triangle dots indicate syndromic (n = 5) and non-syndromic (n = 10) USH2A-RP patients, respectively.

Additionally, time-dependent changes in the same patients were investigated. One syndromic and five non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients had performed HFA evaluations more than twice (Table 5). Rate of changes in MD values were −1.54 (dB/Y) in one syndromic USH2A-RP patient. On the other hand, the MD changes of −0.67 (dB/Y), −0.88 (dB/Y), −0.65 (dB/Y), −0.48 (dB/Y), and −0.34 (dB/Y) were observed in five non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients. These rates of MD changes in the syndromic USH2A-RP patient were higher than the average of the MD changes in non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients (−0.60 (dB/Y)).

Table 5.

Rate of changes in MD values of USH2A-RP patients.

Taken together, these results suggest that 1. truncating USH2A variants contribute to hearing loss in USH2A-RP cases and 2. syndromic USH2A-RP patients had a more severe retinal disease with earlier onset and a more rapid decline in visual function than non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients.

3. Discussion

In this study, genetic analyses of 525 RP patients were conducted using the targeted panel sequencing, and genetic and clinical features were characterized in 36 patients who were found to carry USH2A variants. Molecular diagnosis was made in 287 of 525 RP cases (54.7%) and USH2A disease-causing variants were identified in 6.9% of RP patients (36 of 525 patients) in this cohort. The frequency is similar with previous investigations in Japanese [2], reporting that USH2A is one of the major causal genes in Japanese RP patients.

All syndromic USH2A-RP patients in this cohort noticed their symptoms by their age of 30. The mean age at which our patients noticed symptoms, such as night blindness and visual constriction, was 16.1 years old in syndromic USH2A-RP patients and 26.5 years old in non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients, revealing that the onset of RP was significantly earlier in syndromic patients than in non-syndromic patients (p < 0.05). This trend has also been reported in previous reports of other ethnic groups [23]. In addition, not only age of onset but also RP symptoms were more severe in syndromic patients than in non-syndromic patients. A rapid decline in visual acuity was observed in syndromic USH2A-RP patients as compared to non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients whose acuity was reasonably well-maintained by their 70s. Although the data did not track changes in each patient over a long time, poorer visual acuity prognosis in syndromic USH2A-RP than non-syndromic USH2A-RP cases agreed with a trend in previous studies [22,23]. Similarly, as for visual acuity, syndromic USH2A-RP patients suffered more severe visual field constriction than non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients. In non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients, the rate of MD changes was approximately −0.5 (dB/year), which is the average reported progression rate of RP [27]. In contrast with non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients, one of our syndromic USH2A-RP patients showed the value of −1.5 (dB/year). In our clinic, the Goldmann perimetry is the first-choice visual field test for patients with low vision (lower than 1.0 of logMAR visual acuity), which was more preferably conducted in our syndromic USH2A-RP patients. Indeed 5 of 11 syndromic USH2A-RP patients had difficulty performing visual field tests with HFA due to their severely affected vision. These observations in visual acuity and visual field suggest that eye symptoms of USH2A-RP are more severe in patients with syndromic USH2A-RP than those with non-syndromic USH2A-RP.

Notably, the detection rate of truncating variants is significantly higher in syndromic USH2A-RP patients in this study. Considering characteristics of clinical features and genotype in USH2A-RP cases, truncating variants, which can largely affect protein functions and expression, possibly lead to severe symptoms related to RP and hearing loss. This genotype–phenotype correlation of variants which could contribute to remnant protein functions was reported in CDHR1 [28], ABCA4 [29], and CDH23 [30,31]. Although syndromic RP cases without truncating variants in USH2A have been reported [23], truncating variants were detected in all syndromic USH2A-RP patients in this study, emphasizing the important roles of truncating variants for more severe phenotypes including hearing problems.

The variants frequently detected in this study were p.(Cys934Trp), p.(Gly2752Arg), and c.8559-2A>G. The last variant c.8559-2A>G is reported as a specific variant in the Japanese population [19]. On the contrary, USH2A variants often reported in the Caucasian population, such as p.(Cys759Phe) (pathogenicity of this variant is being reviewed elsewhere [32,33]) and p.(Glu767Serfs*21), were not identified in our Japanese cohort. Interestingly, the most frequent variant p.(Cys934Trp) was common in Chinese and Japanese populations, but other frequent variants differed. The variants often reported in the Chinese population, such as p.(Tyr2854_Arg2894del) and p.(Ser5060Pro), were not identified in our cohort. These observations suggest that there are unique variants in Japanese USH2A-RP patients as ethnic features.

It is not fully understood why USH2A variants lead to a wide range of phenotypes and severity of the diseases. Ush2a-knockout in mice and in zebrafish recapitulated a phenotype of human Usher syndrome with retinal degeneration and hearing problems [16,34]. These models could support our observation that all USH2A-RP patients with two truncating variants (n = 6) developed RP and early-onset hearing loss. Two protein isoforms, a long isoform and a short N-terminal isoform, are spliced from the USH2A gene [11]. Expression of the N-terminal isoform was only detected in the inner ear; in contrast, the long isoform was localized in photoreceptors and ears [16]. Interestingly, supplementation of a shortened form of Ush2a that lacks exon 12 rescued hearing loss in Ush2a-knockout mice [35]. Additionally, the roles of a partner protein, PDZD7, could be different in photoreceptors and inner ears [36]. Remarkably, PDZD7 variants are only responsible for congenital hearing loss, but not for RP [36]. These facts and the accumulation of additional evidence could contribute to better understanding the pathogenesis of USH2A-associated diseases.

In our clinic, we recommend otorhinolaryngologic consultation for both syndromic and non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients to check their hearing ability. The previous study reported that some USH2A-RP patients are not aware of their hearing problems, suggesting non-syndromic USH2A-RP could have mild hearing deterioration [9]. Because we categorized groups of syndromic and non-syndromic USH2A-RP depending on the patients’ interview, possibilities of mis-grouping cannot be ruled out if such patients participated in this study. An additional concern could be that this study did not include patients who have only hearing loss due to USH2A variants. Pathogenic variants of USH2A in hearing loss have been reported in a previous meta-analysis [37]. Accordingly, further evaluations of USH2A-associated diseases from the standpoints both of ophthalmology and otolaryngology will be necessary.

In conclusion, truncating USH2A variants were more frequently identified in syndromic USH2A-RP patients who have congenital hearing loss than in non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients without hearing loss. Syndromic USH2A-RP patients have a more severe retinal disease with earlier-onset and a more rapid decline in visual function than non-syndromic USH2A-RP patients. Truncating variants could contribute to serious functional and tissue damages, suggesting important roles of truncating mutations for the pathogenesis of USH2A-RP, especially syndromic USH2A-RP.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the institutional Review Board of Kobe City Eye Hospital (Protocol no. E19002 and Permit no. ezh200901, 04.09.2020).

4.2. Patients Recruitment or Inclusion Criteria

A total of 525 IRD patients were included in this study. All the patients visited the IRD and Genetic Counseling Clinic in Kobe Eye Center Hospital from June 2015 to April 2020 (except four patients in 2013 and 2015) and gene alterations were identified in the genetic analysis studying IRD. In this cohort, patients with USH2A changes were further evaluated regarding their genetic and phenotypic characteristics.

4.3. Genetic Analysis

All patients underwent DNA sequencing using either a panel of 39 (238 patients) or 50 (287 patients) genes (Table 6) causing inherited retinal diseases which were selected based on previous reports [38,39,40]. USH2A (NM_206933.2) was included in both gene panels. The target capture panel covers entire coding exons and exon–intron boundaries of these genes, except RPGR(ORF15). Targeted libraries were sequenced on an illumina NextSeq500 (NextSeq 500 System, illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Table 6.

The list of genes in our target capture panel.

The interpretation of sequence variants was performed based on the criteria and guidelines recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology [41]. Briefly, the variants shown below were classified as pathogenic variants: 1. null variants, which include nonsense, frameshift, start loss and out-of-frame exon deletion, and splice site (+/- 1,2); 2. variants with an allele frequency less than 5% in Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), 1000 Genomes database, and Human Genetic Variation Databases (HGVD); 3. missense variants which were reported as disease-causing variants in previous reports or predicted a pathogenic effect in silico analysis (SIFT (https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) and PolyPhen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/index.shtml)). Clinvar information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) and previous reports have also been used for the interpretation of variants.

Supplemental sanger sequencing of RPGR(ORF15) was performed in male patients whose pathogenic variants were not detected in panel analysis. Segregation analysis using sanger sequencing was also performed in family members. After a data filtering and interpretation process for the detected variants, the variants were checked against clinical conditions and family history of each patient to determine molecular diagnosis in an expert meeting. More details on the analysis can be found in our previous reports [40].

Sequence variants are described in accordance with recommendations from the Human Genome Variation Society [42].

4.4. Clinical Evaluations

Symptoms and other clinical information such as age, gender, age of onset, family history, and the presence of hearing loss, were obtained from their medical and genetic counseling records. Ophthalmological evaluations were performed in the IRD clinic. Evaluations include best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) with the Snellen chart, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, dilated indirect ophthalmoscopy, ophthalmic imaging including fundus autofluorescence and retinal cross-section with OPTOS 200Tx and a SPECTRALIS_Spectral (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) scanner, full-field electroretinogram (ERG), visual fields with Goldmann perimetry (GP) and Humphrey field analyzer (HFA).

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with R version 3.1.3 (R Core Team (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org/). The Welch Two Sample t-test was used to compare age of onset in each group of syndromic and non-syndromic RP, and Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the characteristics of the genetic mutations in each group. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant in a two-sided test. The value a of visual acuity (a) was converted into the value of Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution (logMAR) for statistical analysis (=log(1/a)). The hand motion value has a logMAR conversion of 2.30, the light sense value has a log MAR conversion of 2.80, and the no light sense value has a logMAR conversion of 2.90 [43,44]. Regarding the visual field condition, Mean Deviation (MD) values which obtain from HFA test were used for statistical analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and A.I.; methodology, A.M. and A.I.; validation, A.M., A.Y. and K.K.; formal analysis, A.M. and A.I.; investigation, A.M., A.Y., K.K., Y.H., M.T. and A.I.; data curation, A.M., A.Y., K.K. and A.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and A.I.; writing—review and editing, A.Y., K.K., Y.H., Y.K., S.K. and M.T.; visualization, A.M., A.Y., K.K. and A.I.; supervision, M.T. and S.K.; project administration, Y.K. and M.T.; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) Highway Program for Realization of Regenerative Medicine (M.T.) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Gant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 19K09984 (A.M).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all individuals who participated in this study. We also thank Osamu Ohara and Ryoji Fujiki (Kazusa DNA Research Institute, Chiba, Japan) for genetic analysis, and Haiming Hu and other members of the Takahashi laboratory for their comments and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| RP | Retinitis Pigmentosa |

| IRD | Inherited Retinal Degenerative Disease |

| USH2A-RP | USH2A-associated RP |

| HFA | Humphrey field analyzer |

| MD | Mean Deviation |

References

- Pontikos, N.; Arno, G.; Jurkute, N.; Schiff, E.; Ba-Abbad, R.; Malka, S.; Gimenez, A.; Georgiou, M.; Wright, G.; Armengol, M.; et al. Genetic Basis of Inherited Retinal Disease in a Molecularly Characterized Cohort of More Than 3000 Families from the United Kingdom. Ophthalmology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyanagi, Y.; Akiyama, M.; Nishiguchi, K.M.; Momozawa, Y.; Kamatani, Y.; Takata, S.; Inai, C.; Iwasaki, Y.; Kumano, M.; Murakami, Y.; et al. Genetic characteristics of retinitis pigmentosa in 1204 Japanese patients. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 56, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparisi, M.J.; Aller, E.; Fuster-García, C.; García-García, G.; Rodrigo, R.; Vázquez-Manrique, R.P.; Blanco-Kelly, F.; Ayuso, C.; Roux, A.F.; Jaijo, T.; et al. Targeted next generation sequencing for molecular diagnosis of Usher syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, P.; Yang, J. Usher syndrome: Hearing loss, retinal degeneration and associated abnormalities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eudy, J.D.; Weston, M.D.; Yao, S.; Hoover, D.M.; Rehm, H.L.; Ma-Edmonds, M.; Yan, D.; Ahmad, I.; Cheng, J.J.; Ayuso, C.; et al. Mutation of a gene encoding a protein with extracellular matrix motifs in Usher syndrome type IIa. Science 1998, 280, 1753–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quesne Stabej, P.; Saihan, Z.; Rangesh, N.; Steele-Stallard, H.B.; Ambrose, J.; Coffey, A.; Emmerson, J.; Haralambous, E.; Hughes, Y.; Steel, K.P.; et al. Comprehensive sequence analysis of nine Usher syndrome genes in the UK National Collaborative Usher Study. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 49, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, C.; Riahi, Z.; Chantot-Bastaraud, S.; Smagghe, L.; Letexier, M.; Marcaillou, C.; Lefèvre, G.M.; Hardelin, J.P.; El-Amraoui, A.; Singh-Estivalet, A.; et al. An innovative strategy for the molecular diagnosis of Usher syndrome identifies causal biallelic mutations in 93% of European patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolta, C.; Sweklo, E.A.; Berson, E.L.; Dryja, T.P. Missense mutation in the USH2A gene: Association with recessive retinitis pigmentosa without hearing loss. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 66, 1975–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenassi, E.; Vincent, A.; Li, Z.; Saihan, Z.; Coffey, A.J.; Steele-Stallard, H.B.; Moore, A.T.; Steel, K.P.; Luxon, L.M.; Héon, E.; et al. A detailed clinical and molecular survey of subjects with nonsyndromic USH2A retinopathy reveals an allelic hierarchy of disease-causing variants. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 23, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, S.Y.; Usami, S. Deafness gene variations in a 1120 nonsyndromic hearing loss cohort: Molecular epidemiology and deafness mutation spectrum of patients in Japan. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2015, 124, 49s–60s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijk, E.; Pennings, R.J.; te Brinke, H.; Claassen, A.; Yntema, H.G.; Hoefsloot, L.H.; Cremers, F.P.; Cremers, C.W.; Kremer, H. Identification of 51 novel exons of the Usher syndrome type 2A (USH2A) gene that encode multiple conserved functional domains and that are mutated in patients with Usher syndrome type II. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiners, J.; Nagel-Wolfrum, K.; Jürgens, K.; Märker, T.; Wolfrum, U. Molecular basis of human Usher syndrome: Deciphering the meshes of the Usher protein network provides insights into the pathomechanisms of the Usher disease. Exp. Eye Res. 2006, 83, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dona, M.; Slijkerman, R.; Lerner, K.; Broekman, S.; Wegner, J.; Howat, T.; Peters, T.; Hetterschijt, L.; Boon, N.; de Vrieze, E.; et al. Usherin defects lead to early-onset retinal dysfunction in zebrafish. Exp. Eye Res. 2018, 173, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, C.; El-Amraoui, A. Usher syndrome (sensorineural deafness and retinitis pigmentosa): Pathogenesis, molecular diagnosis and therapeutic approaches. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2012, 25, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, D.; Zallocchi, M. Usher protein functions in hair cells and photoreceptors. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 46, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Bulgakov, O.V.; Darrow, K.N.; Pawlyk, B.; Adamian, M.; Liberman, M.C.; Li, T. Usherin is required for maintenance of retinal photoreceptors and normal development of cochlear hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 4413–4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujakowska, K.M.; Liu, Q.; Pierce, E.A. Photoreceptor Cilia and Retinal Ciliopathies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.H.; Aycinena, A.R.P.; Sharma, T. Ciliopathy: Usher Syndrome. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1085, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, H.; Ohtsubo, M.; Iwasaki, S.; Hotta, Y.; Usami, S.; Mizuta, K.; Mineta, H.; Minoshima, S. Novel USH2A mutations in Japanese Usher syndrome type 2 patients: Marked differences in the mutation spectrum between the Japanese and other populations. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 56, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Hosono, K.; Suto, K.; Ishigami, C.; Arai, Y.; Hikoya, A.; Hirami, Y.; Ohtsubo, M.; Ueno, S.; Terasaki, H.; et al. The first USH2A mutation analysis of Japanese autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa patients: A totally different mutation profile with the lack of frequent mutations found in Caucasian patients. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 59, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartel, B.P.; Löfgren, M.; Huygen, P.L.; Guchelaar, I.; Lo, A.N.K.N.; Sadeghi, A.M.; van Wijk, E.; Tranebjærg, L.; Kremer, H.; Kimberling, W.J.; et al. A combination of two truncating mutations in USH2A causes more severe and progressive hearing impairment in Usher syndrome type IIa. Hear. Res. 2016, 339, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierrache, L.H.; Hartel, B.P.; van Wijk, E.; Meester-Smoor, M.A.; Cremers, F.P.; de Baere, E.; de Zaeytijd, J.; van Schooneveld, M.J.; Cremers, C.W.; Dagnelie, G.; et al. Visual Prognosis in USH2A-Associated Retinitis Pigmentosa Is Worse for Patients with Usher Syndrome Type IIa Than for Those with Nonsyndromic Retinitis Pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Chen, D.F.; Wang, L.; Wu, S.; Wei, X.; Li, H.; Jin, Z.B.; Sui, R. USH2A variants in Chinese patients with Usher syndrome type II and non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Joo, K.; Oh, J.; Han, J.H.; Park, H.R.; Lee, S.; Oh, D.Y.; Woo, S.J.; Choi, B.Y. Severe or Profound Sensorineural Hearing Loss Caused by Novel USH2A Variants in Korea: Potential Genotype-Phenotype Correlation. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol 2020, 13, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, M.A.; Rosner, B.; Weigel-DiFranco, C.; McGee, T.L.; Dryja, T.P.; Berson, E.L. Disease course in patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa due to the USH2A gene. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 5532–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, Y.; Kurata, K.; Hosono, K.; Suto, K.; Hikoya, A.; Nakanishi, H.; Mizuta, K.; Mineta, H.; Minoshima, S.; Hotta, Y. Visual Outcomes in Japanese Patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa and Usher Syndrome Caused by USH2A Mutations. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 33, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayo, A.; Ueno, S.; Kominami, T.; Nishida, K.; Inooka, D.; Nakanishi, A.; Yasuda, S.; Okado, S.; Takahashi, K.; Matsui, S.; et al. Longitudinal study of visual field changes determined by Humphrey Field Analyzer 10-2 in patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.N.; Kurata, K.; Hosono, K.; Ohtsubo, M.; Ohishi, K.; Sato, M.; Minoshima, S.; Hotta, Y. A Japanese family with cone-rod dystrophy of delayed onset caused by a compound heterozygous combination of novel CDHR1 frameshift and known missense variants. Hum. Genome Var. 2019, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iorio, V.; Orrico, A.; Esposito, G.; Melillo, P.; Rossi, S.; Sbordone, S.; Auricchio, A.; Testa, F.; Simonelli, F. ASSOCIATION BETWEEN GENOTYPE AND DISEASE PROGRESSION IN ITALIAN STARGARDT PATIENTS: A Retrospective Natural History Study. Retina 2019, 39, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuto, L.M.; Bork, J.M.; Weston, M.D.; Askew, J.W.; Fields, R.R.; Orten, D.J.; Ohliger, S.J.; Riazuddin, S.; Morell, R.J.; Khan, S.; et al. CDH23 mutation and phenotype heterogeneity: A profile of 107 diverse families with Usher syndrome and nonsyndromic deafness. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 71, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.M.; Bhatti, R.; Madeo, A.C.; Turriff, A.; Muskett, J.A.; Zalewski, C.K.; King, K.A.; Ahmed, Z.M.; Riazuddin, S.; Ahmad, N.; et al. Allelic hierarchy of CDH23 mutations causing non-syndromic deafness DFNB12 or Usher syndrome USH1D in compound heterozygotes. J. Med. Genet. 2011, 48, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuPont, M.; Jones, E.M.; Xu, M.; Chen, R. Investigating the disease association of USH2A p.C759F variant by leveraging large retinitis pigmentosa cohort data. Ophthalmic. Genet. 2018, 39, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozo, M.G.; Bravo-Gil, N.; Méndez-Vidal, C.; Montero-de-Espinosa, I.; Millán, J.M.; Dopazo, J.; Borrego, S.; Antiñolo, G. Re-evaluation casts doubt on the pathogenicity of homozygous USH2A p.C759F. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2015, 167, 1597–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Liu, X.; Xie, S.; Gao, M.; Liu, F.; Yu, S.; Sun, P.; Wang, C.; Archacki, S.; Lu, Z.; et al. Knockout of ush2a gene in zebrafish causes hearing impairment and late onset rod-cone dystrophy. Hum. Genet. 2018, 137, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendse, N.D.; Lamas, V.; Pawlyk, B.S.; Maeder, M.L.; Chen, Z.Y.; Pierce, E.A.; Liu, Q. In Vivo Assessment of Potential Therapeutic Approaches for USH2A-Associated Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1185, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zheng, T.; Ren, C.; Askew, C.; Liu, X.P.; Pan, B.; Holt, J.R.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J. Deletion of PDZD7 disrupts the Usher syndrome type 2 protein complex in cochlear hair cells and causes hearing loss in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 2374–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouret, G.; Poirsier, C.; Spodenkiewicz, M.; Jaquin, C.; Gouy, E.; Arndt, C.; Labrousse, M.; Gaillard, D.; Doco-Fenzy, M.; Lebre, A.S. Genetics of Usher Syndrome: New Insights from a Meta-analysis. Otol. Neurotol. 2019, 40, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, M.; Oishi, A.; Gotoh, N.; Ogino, K.; Higasa, K.; Iida, K.; Makiyama, Y.; Morooka, S.; Matsuda, F.; Yoshimura, N. Comprehensive molecular diagnosis of a large cohort of Japanese retinitis pigmentosa and Usher syndrome patients by next-generation sequencing. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 7369–7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, Y.; Maeda, A.; Hirami, Y.; Ishigami, C.; Kosugi, S.; Mandai, M.; Kurimoto, Y.; Takahashi, M. Retinitis Pigmentosa with EYS Mutations Is the Most Prevalent Inherited Retinal Dystrophy in Japanese Populations. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 2015, 819760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, A.; Yoshida, A.; Kawai, K.; Arai, Y.; Akiba, R.; Inaba, A.; Takagi, S.; Fujiki, R.; Hirami, Y.; Kurimoto, Y.; et al. Development of a molecular diagnostic test for Retinitis Pigmentosa in the Japanese population. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 62, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Dunnen, J.T.; Dalgleish, R.; Maglott, D.R.; Hart, R.K.; Greenblatt, M.S.; McGowan-Jordan, J.; Roux, A.F.; Smith, T.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Taschner, P.E. HGVS Recommendations for the Description of Sequence Variants: 2016 Update. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 37, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze-Bonsel, K.; Feltgen, N.; Burau, H.; Hansen, L.; Bach, M. Visual acuities “hand motion” and “counting fingers” can be quantified with the freiburg visual acuity test. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Fishman, G.A.; Anderson, R.J.; Tozatti, M.S.; Heckenlively, J.R.; Weleber, R.G.; Edwards, A.O.; Brown, J., Jr. Visual acuity impairment in patients with retinitis pigmentosa at age 45 years or older. Ophthalmology 1999, 106, 1780–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).