Drosophila SLC22 Orthologs Related to OATs, OCTs, and OCTNs Regulate Development and Responsiveness to Oxidative Stress

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

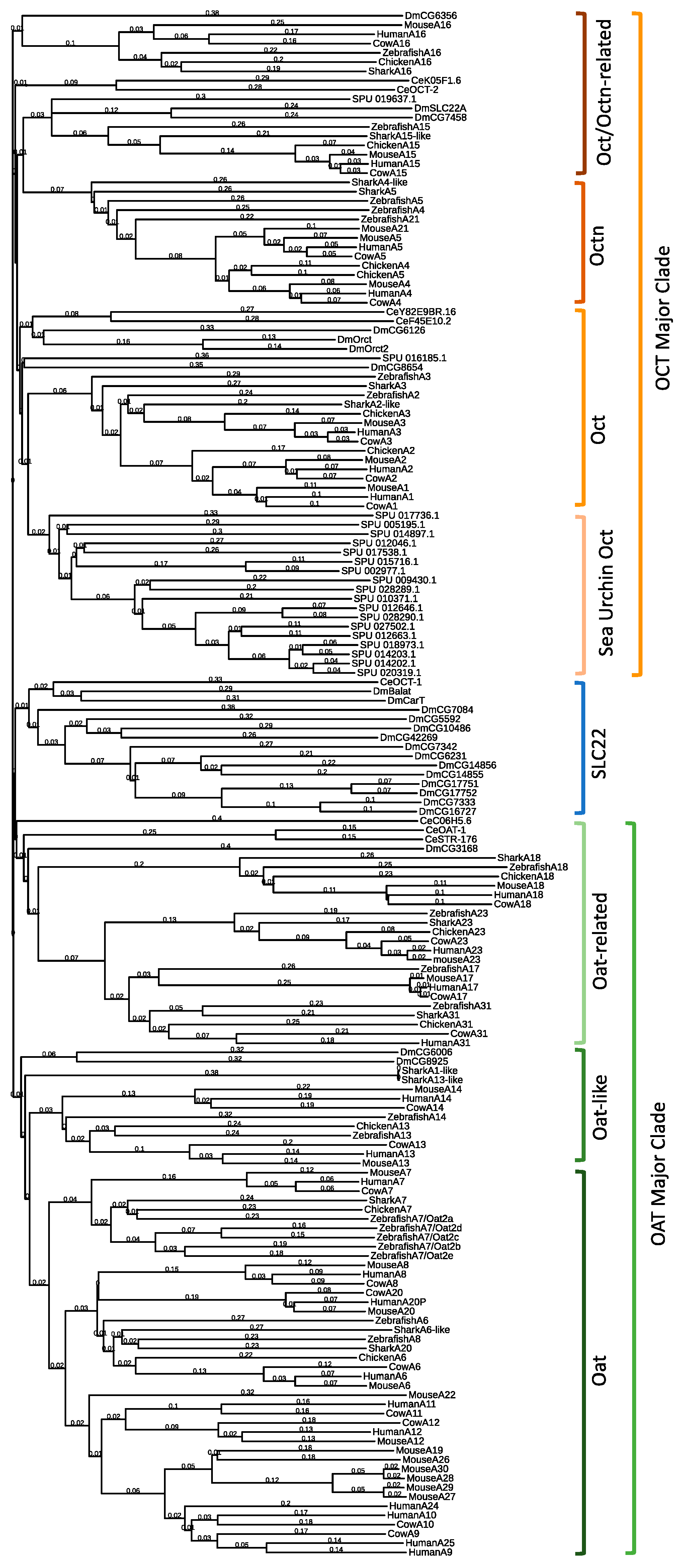

2.1. Drosophila Melanogaster SLC22 Phylogenetic and Genomic Analysis

2.2. Developmental Phenotypes of D. melanogaster SLC22 Knockdowns

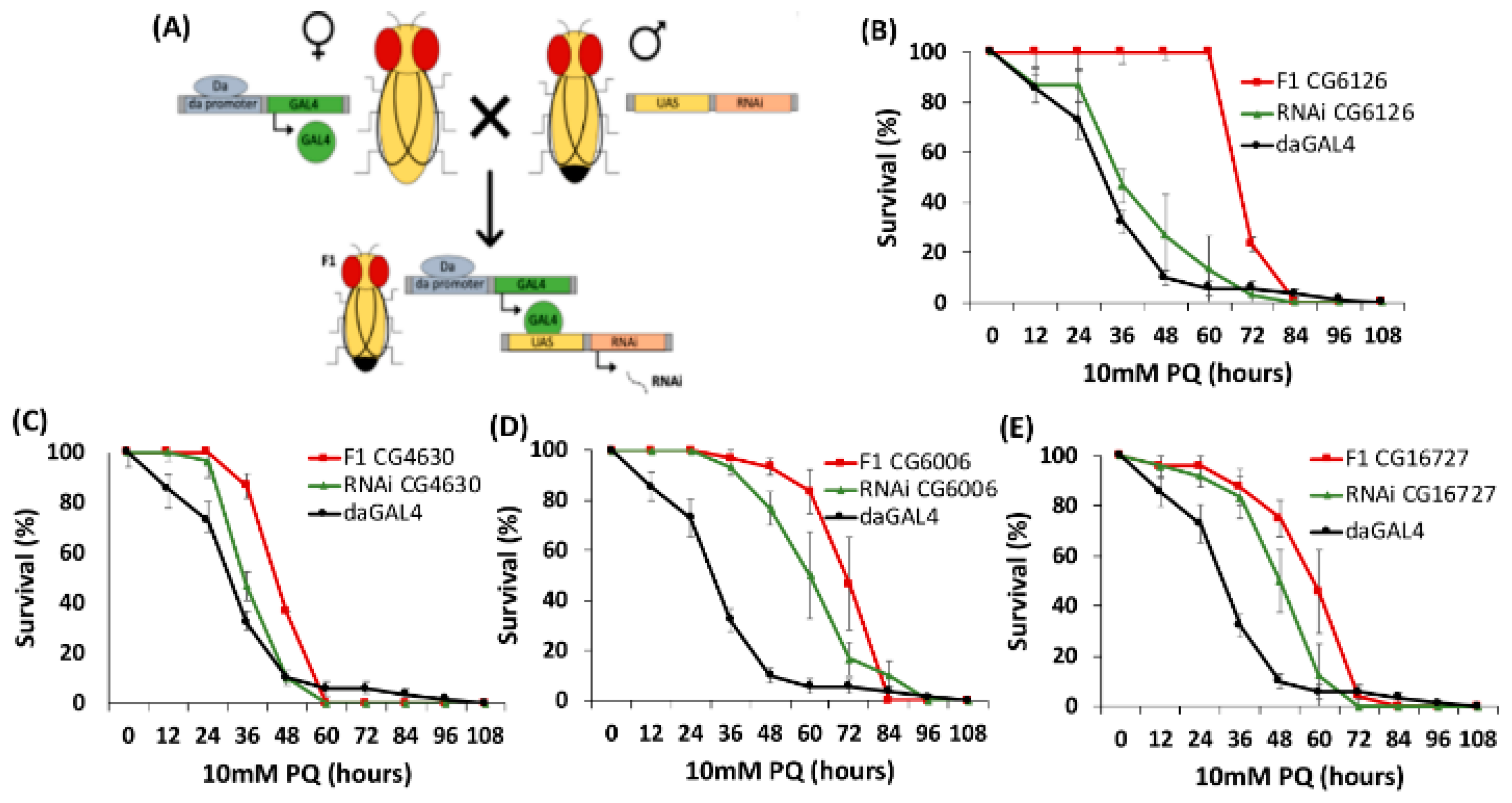

2.3. PQ Resistance Test of D. melanogaster SLC22 Knockdowns

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

4.3. Drosophila Strains and Genetics

4.4. RNAi Developmental Screens and Paraquat Exposure

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SLC22 | Solute Carrier Family 22 |

| OAT | Organic Anion Transporter |

| OCT | Organic Cation Transporter |

| OCTN | Organic Zwitterion Transporter |

| EGT | Ergothioneine |

| MSA | Multiple Sequence Alignment |

| MPP+ | 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium |

| PQ | Paraquat, N,N′-dimethyl-4,4′-bipyridinium dichloride |

| TEA | Tetraethylammonium |

| RSST | Remote Sensing and Signaling Theory |

| RSSN | Remote Sensing and Signaling Network |

| DME | Drug Metabolizing Enzyme |

| GPCR | G Protein Coupled Receptor |

| ABC | ATP-Binding Cassette |

| BDSC | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center |

| HR | Histamine Receptor |

| KO | Knockout |

| URAT1 | Uric Acid Transporter |

| JVS | Juvenile Visceral Steatosis |

| UAS | Upstream Activation Sequence |

| RNAi | Interfering RNA |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| CarT | Carcinine Transporter |

| BalaT | Beta Alanine Transporter |

| SPU | Strongylocentrotus Purpuratus |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle |

References

- César-Razquin, A.; Snijder, B.; Frappier-Brinton, T.; Isserlin, R.; Gyimesi, G.; Bai, X.; Reithmeier, R.A.F.; Hepworth, D.; Hediger, M.A.; Edwards, A.M.; et al. A Call for Systematic Research on Solute Carriers. Cell 2015, 162, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenthal, S.; Bush, K.T.; Nigam, S. A Network of SLC and ABC Transporter and DME Genes Involved in Remote Sensing and Signaling in the Gut-Liver-Kidney Axis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nigam, S. What do drug transporters really do? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 14, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Höglund, P.J.; Nordström, K.; Schiöth, H.B.; Frediksson, R. The solute carrier families have a remarkably long evolutionary history with the majority of the human families present before divergence of Bilaterian species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 28, 1531–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limmer, S.; Weiler, A.; Volkenhoff, A.; Babatz, F.; Klämbt, C. The Drosophila blood-brain barrier: Development and function of a glial endothelium. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eraly, S.A.; Vallon, V.; Rieg, T.; Gangoiti, J.A.; Wikoff, W.R.; Siuzdak, G.; Barshop, B.A.; Nigam, S. Multiple organic anion transporters contribute to net renal excretion of uric acid. Physiol. Genom. 2008, 33, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pandey, U.B.; Nichols, C.D. Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; An, F.; Borycz, J.A.; Borycz, J.; Meinertzhagen, I.A.; Wang, T. Histamine Recycling Is Mediated by CarT, a Carcinine Transporter in Drosophila Photoreceptors. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogasawara, M.; Yamauchi, K.; Satoh, Y.-I.; Yamaji, R.; Inui, K.; Jonker, J.W.; Schinkel, A.H.; Maeyama, K. Recent advances in molecular pharmacology of the histamine systems: Organic cation transporters as a histamine transporter and histamine metabolism. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2006, 101, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, Y.; Xiong, L.; Xu, Y.; Tian, T.; Wang, T. The β-alanine transporter BalaT is required for visual neurotransmission in Drosophila. eLife 2017, 6, e29146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Hattori, K.; Matsuda, N. Regulation of the Cardiovascular System by Histamine. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Volume 241, pp. 239–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Chen, Z. The roles of histamine and its receptor ligands in central nervous system disorders: An update. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 175, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Moussian, B.; Schaeffeler, E.; Schwab, M.; Nies, A.T. The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster as an innovative preclinical ADME model for solute carrier membrane transporters, with consequences for pharmacology and drug therapy. Drug Discov. Today 2018, 23, 1746–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, F.; Schmid, D.; Owens, W.A.; Gould, G.; Apuschkin, M.; Kudlacek, O.; Salzer, I.; Boehm, S.; Chiba, P.; Williams, P.H.; et al. An unsuspected role for organic cation transporter 3 in the actions of amphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 2408–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chintapalli, V.R.; Wang, J.; Dow, J.A.T. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwart, R.; Verhaagh, S.; Buitelaar, M.; Popp-Snijders, C.; Barlow, D.P. Impaired Activity of the Extraneuronal Monoamine Transporter System Known as Uptake-2 in Orct3/Slc22a3-Deficient Mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 4188–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jonker, J.W.; Wagenaar, E.; van Eijl, S.; Schinkel, A.H. Deficiency in the Organic Cation Transporters 1 and 2 (Oct1/Oct2 [Slc22a1/Slc22a2]) in Mice Abolishes Renal Secretion of Organic Cations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 7902–7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, C.; Nigam, K.B.; Date, R.C.; Bush, K.T.; Springer, S.A.; Saier, M.H.; Wu, W.; Nigam, S.K. Evolutionary Analysis and Classification of OATs, OCTs, OCTNs, and Other SLC22 Transporters: Structure-Function Implications and Analysis of Sequence Motifs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pavlova, A.; Sakurai, H.; Leclercq, B.; Beier, D.R.; Yu, A.S.; Nigam, S. Developmentally regulated expression of organic ion transporters NKT (OAT1), OCT1, NLT (OAT2), and Roct. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2000, 278, F635–F643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallon, V.; Eraly, S.A.; Wikoff, W.R.; Rieg, T.; Kaler, G.; Truong, D.M.; Ahn, S.-Y.; Mahapatra, N.R.; Mahata, S.K.; Gangoiti, J.A.; et al. Organic Anion Transporter 3 Contributes to the Regulation of Blood Pressure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bush, K.T.; Wu, W.; Lun, C.; Nigam, S. The drug transporter OAT3 (SLC22A8) and endogenous metabolite communication via the gut–liver–kidney axis. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 15789–15803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eraly, S.A.; Vallon, V.; Vaughn, D.A.; Gangoiti, J.A.; Richter, K.; Nagle, M.; Monte, J.C.; Rieg, T.; Truong, D.M.; Long, J.M.; et al. Decreased Renal Organic Anion Secretion and Plasma Accumulation of Endogenous Organic Anions inOAT1Knock-out Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 281, 5072–5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sweet, D.; Miller, D.S.; Pritchard, J.B.; Fujiwara, Y.; Beier, D.R.; Nigam, S. Impaired Organic Anion Transport in Kidney and Choroid Plexus of Organic Anion Transporter 3 (Oat3(Slc22a8)) Knockout Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 26934–26943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahn, S.-Y.; Jamshidi, N.; Mo, M.L.; Wu, W.; Eraly, S.A.; Dnyanmote, A.; Bush, K.T.; Gallegos, T.F.; Sweet, D.; Palsson, B.Ø.; et al. Linkage of Organic Anion Transporter-1 to Metabolic Pathways through Integrated “Omics”-driven Network and Functional Analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 31522–31531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kato, Y.; Kubo, Y.; Iwata, D.; Kato, S.; Sudo, T.; Sugiura, T.; Kagaya, T.; Wakayama, T.; Hirayama, A.; Sugimoto, M.; et al. Gene Knockout and Metabolome Analysis of Carnitine/Organic Cation Transporter OCTN1. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nezu, J.-I.; Tamai, I.; Oku, A.; Ohashi, R.; Yabuuchi, H.; Hashimoto, N.; Nikaido, H.; Sai, Y.; Koizumi, A.; Shoji, Y.; et al. Primary systemic carnitine deficiency is caused by mutations in a gene encoding sodium ion-dependent carnitine transporter. Nat. Genet. 1999, 21, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, T.J.; Gallagher, R.C.; Brown, C.; Castro, R.A.; Lagpacan, L.L.; Brett, C.M.; Taylor, T.R.; Carlson, E.J.; Ferrin, T.; Burchard, E.G.; et al. Functional Genetic Diversity in the High-Affinity Carnitine Transporter OCTN2 (SLC22A5). Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 1602–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Momper, J.D.; Nigam, S. Developmental regulation of kidney and liver solute carrier and ATP-binding cassette drug transporters and drug metabolizing enzymes: The role of remote organ communication. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momper, J.D.; Yang, J.; Gockenbach, M.; Vaida, F.; Nigam, S.K. Dynamics of Organic Anion Transporter-Mediated Tubular Secretion during Postnatal Human Kidney Development and Maturation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sweeney, D.E.; Vallon, V.; Rieg, T.; Wu, W.; Gallegos, T.F.; Nigam, S. Functional Maturation of Drug Transporters in the Developing, Neonatal, and Postnatal Kidney. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 80, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martovetsky, G.; Tee, J.B.; Nigam, S. Hepatocyte nuclear factors 4α and 1α regulate kidney developmental expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 84, 808–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bainbridge, S.P.; Bownes, M. Staging the metamorphosis of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1981, 66, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Song, S.; Weng, R.; Verma, P.; Kugler, J.-M.; Buescher, M.; Rouam, S.; Cohen, S. Systematic Study of Drosophila MicroRNA Functions Using a Collection of Targeted Knockout Mutations. Dev. Cell 2014, 31, 784–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCormack, A.L.; Mona, T.; Amy, B.M.-B.; Christine, T.J.; William, L.; Deborah, A.C.-S.; Donato, A.D.M. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson’s disease: Selective degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons caused by the herbicide paraquat. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 10, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, G.M.; Doherty, M.D. Free radical mediated cell toxicity by redox cycling chemicals. Br. J. Cancer 1987, 8, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bus, J.S.; Gibson, J.E. Paraquat: Model for oxidant-initiated toxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 1984, 55, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.K.; Sindhu, K.K. Oxidative stress and metabolic syndrome. Life Sci. 2009, 84, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, B.N.; Cathcart, R.; Schwiers, E.; Hochstein, P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: A hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 6858–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheah, I.K.; Halliwell, B. Ergothioneine; antioxidant potential, physiological function and role in disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2012, 1822, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marchette, L.D.; Wang, H.; Li, F.; Babizhayev, M.A.; Kasus-Jacobi, A. Carcinine Has 4-Hydroxynonenal Scavenging Property and Neuroprotective Effect in Mouse Retina. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 3572–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhart, D.C.; Granados, J.; Shi, D.; Milton, H.S., Jr.; Baker, M.E.; Abagyan, R.; Nigam, S. Systems Biology Analysis Reveals Eight SLC22 Transporter Subgroups, Including OATs, OCTs, and OCTNs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gai, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cervantes-Sandoval, I.; Davis, R.L. Drosophila SLC22A Transporter Is a Memory Suppressor Gene that Influences Cholinergic Neurotransmission to the Mushroom Bodies. Neuron 2016, 90, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Haddad, G.G. Drosophila dMRP4 regulates responsiveness to O2 deprivation and development under hypoxia. Physiol. Genom. 2007, 29, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nigam, S. The SLC22 Transporter Family: A Paradigm for the Impact of Drug Transporters on Metabolic Pathways, Signaling, and Disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 58, 663–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, A.K.; Li, J.G.; Lall, K.; Shi, D.; Bush, K.T.; Bhatnagar, V.; Abagyan, R.; Nigam, S.K. Unique metabolite preferences of the drug transporters OAT1 and OAT3 analyzed by machine learning. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 1829–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrae, U.; Singh, J.; Ziegler-Skylakakis, K. Pyruvate and related α-ketoacids protect mammalian cells in culture against hydrogen peroxide-induced cytotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 1985, 28, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-M.; Zhang, L.; Giacomini, K.M. The International Transporter Consortium: A Collaborative Group of Scientists from Academia, Industry, and the FDA. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 87, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yin, J.; Sun, W.; Li, F.; Hong, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; et al. VARIDT 1.0: Variability of drug transporter database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D1042–D1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraly, S.A.; Monte, J.C.; Nigam, S. Novel slc22 transporter homologs in fly, worm, and human clarify the phylogeny of organic anion and cation transporters. Physiol. Genom. 2004, 18, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenesen, E.; Moehlman, A.; Krämer, H. The carcinine transporter CarT is required in Drosophila photoreceptor neurons to sustain histamine recycling. eLife 2015, 4, e10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geer, B.W.; Vovis, G.F. The effects of choline and related compounds on the growth and development ofDrosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Zool. 1965, 158, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enomoto, A.; Wempe, M.; Tsuchida, H.; Goto, A.; Sakamoto, A.; Cha, S.H.; Anzai, N.; Niwa, T.; Kanai, Y.; Endou, H.; et al. Molecular Identification of a Novel Carnitine Transporter Specific to Human Testis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 36262–36271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eraly, S.A.; Nigam, S. Novel human cDNAs homologous to Drosophila Orct and mammalian carnitine transporters. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 297, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochini, L.; Scalise, M.; Di Silvestre, S.; Belviso, S.; Pandolfi, A.; Arduini, A.; Bonomini, M.; Indiveri, C. Acetylcholine and acetylcarnitine transport in peritoneum: Role of the SLC22A4 (OCTN1) transporter. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Huang, W.; Prasad, P.D.; Seth, P.; Rajan, D.P.; Leibach, F.H.; Chen, J.; Conway, S.J.; Ganapathy, V. Functional characteristics and tissue distribution pattern of organic cation transporter 2 (OCTN2), an organic cation/carnitine transporter. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999, 290, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Tamai, I.; Ohashi, R.; Nezu, J.; Sai, Y.; Kobayashi, D.; Oku, A.; Shimane, M.; Tsuji, A. Molecular and Functional Characterization of Organic Cation/Carnitine Transporter Family in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 40064–40072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papatheodorou, I.; Fonseca, N.A.; Keays, M.; Tang, A.; Barrera, E.; Bazant, W.; Burke, M.; Füllgrabe, A.; Fuentes, A.M.-P.; George, N.; et al. Expression Atlas: Gene and protein expression across multiple studies and organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D246–D251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenhein, B.; Becker, A.; Busold, C.; Beckmann, B.; Hoheisel, J.D.; Technau, G.M. Expression profiling of glial genes during Drosophila embryogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2006, 296, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindsay, S.; Xu, Y.; Lisgo, S.N.; Harkin, L.F.; Copp, A.J.; Gerrelli, D.; Clowry, G.J.; Talbot, A.; Keogh, M.J.; Coxhead, J.; et al. HDBR Expression: A Unique Resource for Global and Individual Gene Expression Studies during Early Human Brain Development. Front. Neuroanat. 2016, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berridge, M.J.; Oschman, J.L. A structural basis for fluid secretion by malpighian tubules. Tissue Cell 1969, 1, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, S.W.; Stecula, A.; Chien, H.-C.; Zou, L.; Feofanova, E.V.; Van Borselen, M.; Cheung, K.W.K.; Yousri, N.A.; Suhre, K.; Kinchen, J.M.; et al. Unraveling the functional role of the orphan solute carrier, SLC22A24 in the transport of steroid conjugates through metabolomic and genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nigam, S.K.; Bush, K.T.; Martovetsky, G.; Ahn, S.-Y.; Liu, H.C.; Richard, E.; Bhatnagar, V.; Wu, W. The organic anion transporter (OAT) family: A systems biology perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 83–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fork, C.; Bauer, T.; Golz, S.; Geerts, A.; Weiland, J.; Del Turco, D.; Schömig, E.; Gründemann, D. OAT2 catalyses efflux of glutamate and uptake of orotic acid. Biochem. J. 2011, 436, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sawa, K.; Uematsu, T.; Korenaga, Y.; Hirasawa, R.; Kikuchi, M.; Murata, K.; Zhang, J.; Gai, X.; Sakamoto, K.; Koyama, T.; et al. Krebs Cycle Intermediates Protective against Oxidative Stress by Modulating the Level of Reactive Oxygen Species in Neuronal HT22 Cells. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chahine, S.; Campos, A.; O’Donnell, M.J. Genetic knockdown of a single organic anion transporter alters the expression of functionally related genes in Malpighian tubules of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 215, 2601–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chahine, S.; Seabrooke, S.; O’Donnell, M.E. Effects of genetic knock-down of organic anion transporter genes on secretion of fluorescent organic ions by malpighian tubules of drosophila melanogaster. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 81, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.-Y.; Nigam, S. Toward a systems level understanding of organic anion and other multispecific drug transporters: A remote sensing and signaling hypothesis. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 76, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, W.; Dnyanmote, A.V.; Nigam, S. Remote communication through solute carriers and ATP binding cassette drug transporter pathways: An update on the remote sensing and signaling hypothesis. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 79, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cary, G.; Cameron, R.A.; Hinman, V.F. EchinoBase: Tools for Echinoderm Genome Analyses; Humana Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1757, pp. 349–369. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.; Howe, K.L.; Harris, T.; Arnaboldi, V.; Cain, S.; Chan, J.; Chen, W.J.; Davis, P.; Gao, S.; Grove, C.; et al. WormBase 2017: Molting into a new stage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D869–D874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.; Zweig, A.S.; Villarreal, C.; Tyner, C.; Speir, M.L.; Rosenbloom, K.R.; Raney, B.J.; Lee, C.M.; Lee, B.T.; Karolchik, D.; et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D762–D769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marygold, S.J.; Crosby, M.A.; Goodman, J.L. Using FlyBase, a Database of Drosophila Genes and Genomes; Humana Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1478, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sievers, F.; Wilm, A.; Dineen, D.; Gibson, T.J.; Karplus, K.; Li, W.; López, R.; McWilliam, H.; Remmert, M.; Soeding, J.; et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011, 7, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madeira, F.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, J.; Buso, N.; Gur, T.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Basutkar, P.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Potter, S.; Finn, R.D.; et al. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W636–W641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: Recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W256–W259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, L.A.; Holderbaum, L.; Tao, R.; Hu, Y.; Sopko, R.; McCall, K.; Yang-Zhou, N.; Flockhart, I.; Binari, R.; Shim, H.-S.; et al. The Transgenic RNAi Project at Harvard Medical School: Resources and Validation. Genetics 2015, 201, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccin, A. Efficient and heritable functional knock-out of an adult phenotype in Drosophila using a GAL4-driven hairpin RNA incorporating a heterologous spacer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Gene ID | Expression Patterns | Phenotypic Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Loci | Tissue/Sexual Dimorphism | Physiological Role | Substrates | |

| CG3168 | X: 6,720,004-6,739,986 | CNS, glial specific, ubiquitously expressed in other tissues | ||

| CarT/CG9317 | 2L: 20,727,151-20,730,282 | head, brain, eye, salivary gland | histamine recycling in photoreceptor neurons | carcinine, neurotransmitters |

| BalaT/CG3790 | 2R: 12,872,787-2,875,012 | head, brain, eye, midgut | histamine recycling in photoreceptor neurons | Beta-alanine |

| CG4630 | 2R: 13,215,659-13,219,247 | ubiquitously expressed, except for ovary and testis | ||

| CG8654 | 2R: 19,979,242-19,984,895 | ubiquitously expressed, except for larval and adult midgut and ovaries | ||

| CG5592 | 3L: 5,897,638-5,899,395 | Testis, males only | ||

| CG10486 | 3L: 5,904,211-5,906,699 | testis | ||

| CG42269 | 3L: 6,066,296-6,071,545 | head, hindgut | ||

| CG7458 | 3L: 21,955,110-21,958,041 | ubiquitously expressed, lower expression in larval CNS and adult brain | ||

| SLC22A/CG7442 | 3L: 21,934,704-21,938,636 | ubiquitously expressed, except for ovary and testis | memory suppressor gene | MPP, Choline, Acetylcholine, Dopamine, Histamine, Serotonin, TEA, Betaine, L-carnitine |

| CG14855 | 3R: 14,796,305-14,798,474 | CNS, brain | ||

| CG14856 | 3R: 14,798,986-14,801,163 | hindgut, midgut, heart, higher expression in larva | ||

| CG6006 | 3R: 16,154,982-16,171,766 | head, brain, eye, hindgut | ||

| CG8925 | 3R: 16,171,991-16,180,475 | head, eye, salivary gland, midgut, hindgut | ||

| CG6126 | 3R: 16,198,000-16,203,083 | ubiquitously expressed, except for testis | ||

| CG7333 | 3R: 19,600,635-19,602,629 | testis | ||

| CG7342 | 3R: 19,603,375-19,606,475 | CNS, midgut, Malpighian tubule, hindgut, testis | ||

| CG17751 | 3R: 19,607,254-19,609,322 | Malpighian tubule, heart | ||

| CG17752 | 3R: 19,607,254-19,609,322 | Malpighian tubule | ||

| CG16727 | 3R: 19,613,381-19,615,784 | Malpighian tubule, testis | ||

| CG6231 | 3R: 19,616,024-19,632,718 | Ubiquitously expressed, lower expression in adult midgut | ||

| CG7084 | 3R: 22,298,805-22,304,420 | CNS, midgut, Malpighian tubule, hindgut | ||

| Orct2/CG13610 | 3R: 24,273,029-24,275,728 | ubiquitously expressed, except for Malpighian tubules | ||

| Orct/CG6331 | 3R: 24,276,260-24,278,792 | ubiquitously expressed, lower expression in ovaries | ||

| CG6356 | 3R: 24,283,955-24,288,617 | CNS, testis | putative A16 ortholog/carnitine transporter | |

| Gene ID | Phylogenetic Relationship | RNAi BDSC Stock ID | Phenotypes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup/Subclade | Transporter | Tested | Pupa Stage Arrest | PQR | ||

| CG3168 | Oat-related | A18 | 29301 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| CarT/CG9317 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | |||||

| BalaT/CG3790 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | 67274 | ✓ | |||

| CG4630 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | 61249 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| CG8654 | Oct subclade | 57428 | ✓ | |||

| CG5592 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | |||||

| CG10486 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | |||||

| CG42269 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | |||||

| CG7458 | Octn-related | A15 | ||||

| SLC22A/CG7442 | Octn-related | A15 | 35817 | ✓ | ✓ [43] confirmed in this study | |

| CG14855 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | |||||

| CG14856 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | |||||

| CG6006 | Oat related, A16 * | 55282 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| CG8925 | Oat related, A16 * | |||||

| CG6126 | Oct subclade | 56038 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| CG7333 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | 57433 | ✓ | |||

| CG7342 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | |||||

| CG17751 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | |||||

| CG17752 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | |||||

| CG16727 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | 57434 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| CG6231 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | 63013 | ✓ | |||

| CG7084 | neither Oct or Oat Major Clade | 42767 | ✓ | |||

| Orct2/CG13610 | Oct subclade | 57583 | ✓ | |||

| Orct/CG6331 | Oct subclade | 60125 | ✓ | |||

| CG6356 | Octn | A16 | 28745 | ✓ | ✓ | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Engelhart, D.C.; Azad, P.; Ali, S.; Granados, J.C.; Haddad, G.G.; Nigam, S.K. Drosophila SLC22 Orthologs Related to OATs, OCTs, and OCTNs Regulate Development and Responsiveness to Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21062002

Engelhart DC, Azad P, Ali S, Granados JC, Haddad GG, Nigam SK. Drosophila SLC22 Orthologs Related to OATs, OCTs, and OCTNs Regulate Development and Responsiveness to Oxidative Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(6):2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21062002

Chicago/Turabian StyleEngelhart, Darcy C., Priti Azad, Suwayda Ali, Jeffry C. Granados, Gabriel G. Haddad, and Sanjay K. Nigam. 2020. "Drosophila SLC22 Orthologs Related to OATs, OCTs, and OCTNs Regulate Development and Responsiveness to Oxidative Stress" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 6: 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21062002

APA StyleEngelhart, D. C., Azad, P., Ali, S., Granados, J. C., Haddad, G. G., & Nigam, S. K. (2020). Drosophila SLC22 Orthologs Related to OATs, OCTs, and OCTNs Regulate Development and Responsiveness to Oxidative Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(6), 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21062002