Nature versus Number: Monocytes in Cardiovascular Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

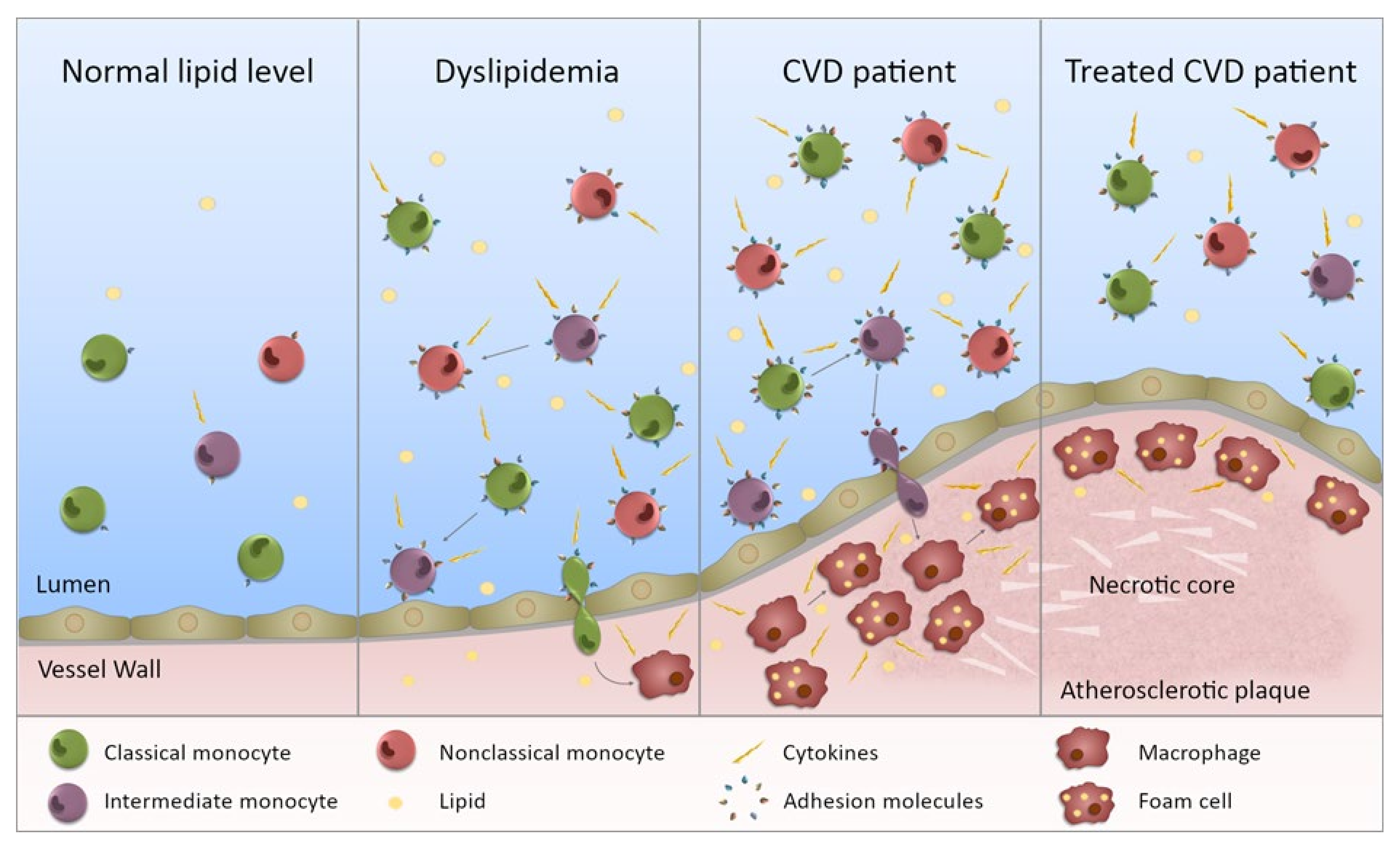

2. Monocyte Subset Proportions in CVD

3. Monocyte Functional Changes in CVD

4. Monocyte Count/Percentage Changes Relative to Lipids

5. Monocyte Functional Changes Associated with Lipid Levels

6. Impact of Functional Changes

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Knuuti, J.; Wijns, W.; Saraste, A.; Capodanno, D.; Barbato, E.; Funck-Brentano, C.; Prescott, E.; Storey, R.F.; Deaton, C.; Cuisset, T.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 407–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentzon, J.F.; Otsuka, F.; Virmani, R.; Falk, E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1852–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 3333–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khot, U.N.; Khot, M.B.; Bajzer, C.T.; Sapp, S.K.; Ohman, E.M.; Brener, S.J.; Ellis, S.G.; Lincoff, A.M.; Topol, E.J. Prevalence of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA 2003, 290, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nelson, R.H. Hyperlipidemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Prim. Care 2013, 40, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ridker, P.M.; Danielson, E.; Fonseca, F.A.; Genest, J.; Gotto, A.M., Jr.; Kastelein, J.J.; Koenig, W.; Libby, P.; Lorenzatti, A.J.; MacFadyen, J.G.; et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 2195–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; Fonseca, F.; Nicolau, J.; Koenig, W.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosser, D.M.; Edwards, J.P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoger, J.L.; Gijbels, M.J.; van der Velden, S.; Manca, M.; van der Loos, C.M.; Biessen, E.A.; Daemen, M.J.; Lutgens, E.; de Winther, M.P. Distribution of macrophage polarization markers in human atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2012, 225, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tarique, A.A.; Logan, J.; Thomas, E.; Holt, P.G.; Sly, P.D.; Fantino, E. Phenotypic, functional, and plasticity features of classical and alternatively activated human macrophages. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 53, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medbury, H.J.; James, V.; Ngo, J.; Hitos, K.; Wang, Y.; Harris, D.C.; Fletcher, J.P. Differing association of macrophage subsets with atherosclerotic plaque stability. Int. Angiol. 2013, 32, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S.; Locati, M.; Mantovani, A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: New molecules and patterns of gene expression. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 7303–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

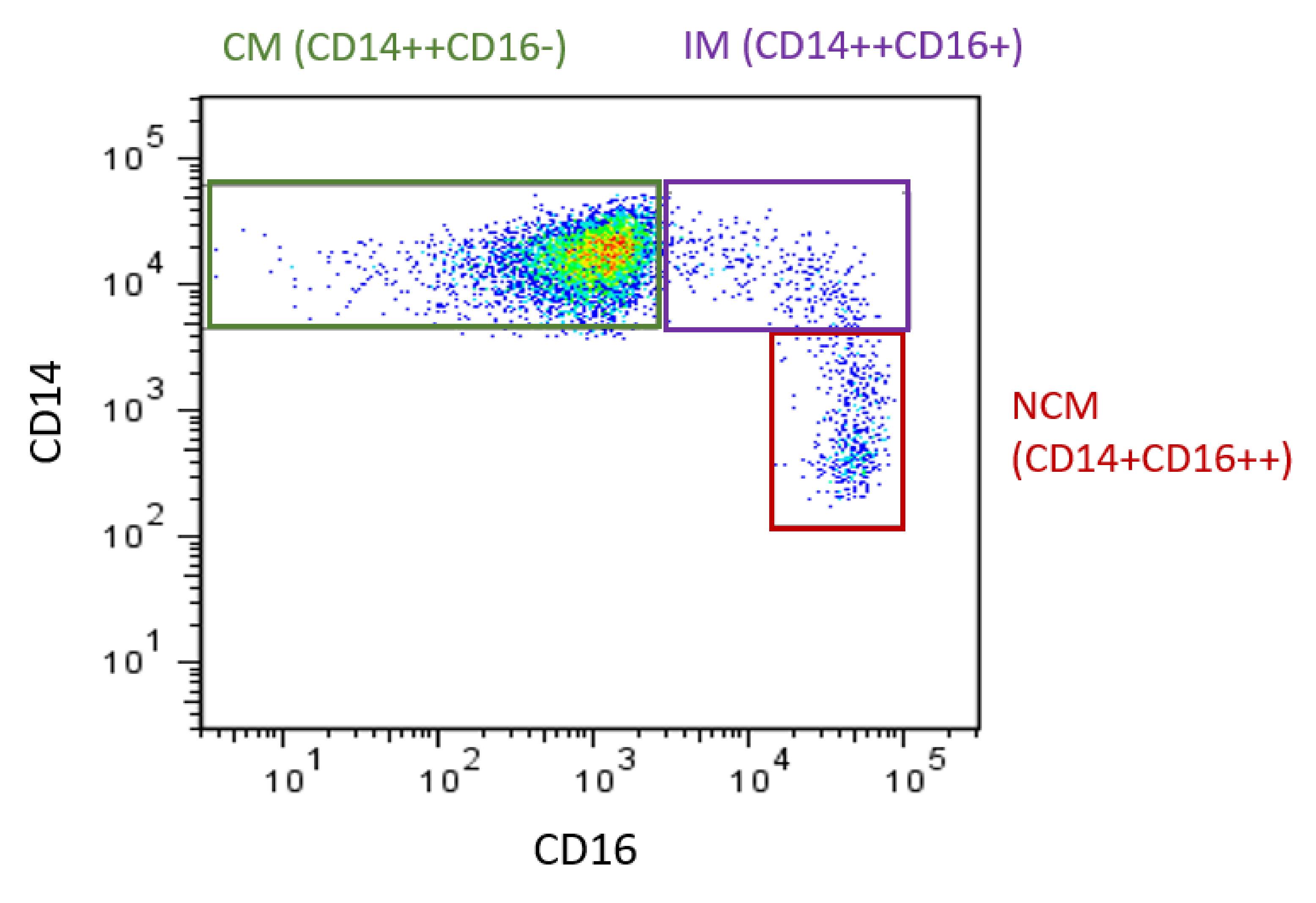

- Weber, C.; Shantsila, E.; Hristov, M.; Caligiuri, G.; Guzik, T.; Heine, G.H.; Hoefer, I.E.; Monaco, C.; Peter, K.; Rainger, E.; et al. Role and analysis of monocyte subsets in cardiovascular disease. Joint consensus document of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Working Groups “Atherosclerosis & Vascular Biology” and “Thrombosis”. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 116, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Poupel, L.; Boissonnas, A.; Hermand, P.; Dorgham, K.; Guyon, E.; Auvynet, C.; Charles, F.S.; Lesnik, P.; Deterre, P.; Combadiere, C. Pharmacological inhibition of the chemokine receptor, CX3CR1, reduces atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 2297–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schlitt, A.; Heine, G.H.; Blankenberg, S.; Espinola-Klein, C.; Dopheide, J.F.; Bickel, C.; Lackner, K.J.; Iz, M.; Meyer, J.; Darius, H.; et al. CD14+CD16+ monocytes in coronary artery disease and their relationship to serum TNF-alpha levels. Thromb. Haemost. 2004, 92, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock, L.; Ancuta, P.; Crowe, S.; Dalod, M.; Grau, V.; Hart, D.N.; Leenen, P.J.; Liu, Y.J.; MacPherson, G.; Randolph, G.J.; et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood 2010, 116, e74–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawada, A.M.; Fell, L.H.; Untersteller, K.; Seiler, S.; Rogacev, K.S.; Fliser, D.; Ziegler-Heitbrock, L.; Heine, G.H. Comparison of two different strategies for human monocyte subsets gating within the large-scale prospective CARE FOR HOMe Study. Cytom. A 2015, 87, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawada, A.M.; Rogacev, K.S.; Schirmer, S.H.; Sester, M.; Bohm, M.; Fliser, D.; Heine, G.H. Monocyte heterogeneity in human cardiovascular disease. Immunobiology 2012, 217, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantsila, E.; Tapp, L.D.; Wrigley, B.J.; Pamukcu, B.; Apostolakis, S.; Montoro-Garcia, S.; Lip, G.Y. Monocyte subsets in coronary artery disease and their associations with markers of inflammation and fibrinolysis. Atherosclerosis 2014, 234, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamers, A.A.J.; Dinh, H.Q.; Thomas, G.D.; Marcovecchio, P.; Blatchley, A.; Nakao, C.S.; Kim, C.; McSkimming, C.; Taylor, A.M.; Nguyen, A.T.; et al. Human Monocyte Heterogeneity as Revealed by High-Dimensional Mass Cytometry. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merah-Mourah, F.; Cohen, S.O.; Charron, D.; Mooney, N.; Haziot, A. Identification of Novel Human Monocyte Subsets and Evidence for Phenotypic Groups Defined by Interindividual Variations of Expression of Adhesion Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.K.; Williams, H.; Li, S.C.H.; Fletcher, J.P.; Medbury, H.J. Monocyte Subset Recruitment Marker Profile Is Inversely Associated with Blood ApoA1 Levels. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 616305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, Y.; Imanishi, T.; Taruya, A.; Aoki, H.; Masuno, T.; Shiono, Y.; Komukai, K.; Tanimoto, T.; Kitabata, H.; Akasaka, T. Circulating CD14+CD16+ monocyte subsets as biomarkers of the severity of coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina pectoris. Circ. J. 2012, 76, 2412–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Afanasieva, O.I.; Filatova, A.Y.; Arefieva, T.I.; Klesareva, E.A.; Tyurina, A.V.; Radyukhina, N.V.; Ezhov, M.V.; Pokrovsky, S.N. The Association of Lipoprotein(a) and Circulating Monocyte Subsets with Severe Coronary Atherosclerosis. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis 2021, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildgruber, M.; Aschenbrenner, T.; Wendorff, H.; Czubba, M.; Glinzer, A.; Haller, B.; Schiemann, M.; Zimmermann, A.; Berger, H.; Eckstein, H.H.; et al. The “Intermediate” CD14(++)CD16(+) monocyte subset increases in severe peripheral artery disease in humans. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, S.; Zhou, X.; Ge, L.; Ji, W.J.; Shi, R.; Lu, R.Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Guo, Z.Z.; Zhao, J.H.; Jiang, T.M.; et al. Monocyte subsets and monocyte-platelet aggregates in patients with unstable angina. J. Thromb. Thrombol. 2014, 38, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbrana, S.; Campolo, J.; Clemente, A.; Bastiani, L.; Cecchettini, A.; Ceccherini, E.; Caselli, C.; Neglia, D.; Parodi, O.; Chiappino, D.; et al. Blood Monocyte Phenotype Fingerprint of Stable Coronary Artery Disease: A Cross-Sectional Substudy of SMARTool Clinical Trial. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8748934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urra, X.; Villamor, N.; Amaro, S.; Gomez-Choco, M.; Obach, V.; Oleaga, L.; Planas, A.M.; Chamorro, A. Monocyte subtypes predict clinical course and prognosis in human stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009, 29, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogacev, K.S.; Cremers, B.; Zawada, A.M.; Seiler, S.; Binder, N.; Ege, P.; Grosse-Dunker, G.; Heisel, I.; Hornof, F.; Jeken, J.; et al. CD14++CD16+ monocytes independently predict cardiovascular events: A cohort study of 951 patients referred for elective coronary angiography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 1512–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tallone, T.; Turconi, G.; Soldati, G.; Pedrazzini, G.; Moccetti, T.; Vassalli, G. Heterogeneity of human monocytes: An optimized four-color flow cytometry protocol for analysis of monocyte subsets. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2011, 4, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopheide, J.F.; Obst, V.; Doppler, C.; Radmacher, M.C.; Scheer, M.; Radsak, M.P.; Gori, T.; Warnholtz, A.; Fottner, C.; Daiber, A.; et al. Phenotypic characterisation of pro-inflammatory monocytes and dendritic cells in peripheral arterial disease. Thromb. Haemost. 2012, 108, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapp, L.D.; Shantsila, E.; Wrigley, B.J.; Pamukcu, B.; Lip, G.Y. The CD14++CD16+ monocyte subset and monocyte-platelet interactions in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2012, 10, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturhan, H.; Ungern-Sternberg, S.N.; Langer, H.; Gawaz, M.; Geisler, T.; May, A.E.; Seizer, P. Regulation of EMMPRIN (CD147) on monocyte subsets in patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. Thromb. Res. 2015, 135, 1160–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, T.; Nazarewicz, R.R.; Wallis, B.B.; Yanes, R.E.; Watanabe, R.; Hilhorst, M.; Tian, L.; Harrison, D.G.; Giacomini, J.C.; Assimes, T.L.; et al. The glycolytic enzyme PKM2 bridges metabolic and inflammatory dysfunction in coronary artery disease. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhuang, J.; Han, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhu, G.; Singh, S.; Chen, L.; Zhu, M.; Chen, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, X. Comparison of circulating dendritic cell and monocyte subsets at different stages of atherosclerosis: Insights from optical coherence tomography. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017, 17, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Cassorla, G.; Pertsoulis, N.; Patel, V.; Vicaretti, M.; Marmash, N.; Hitos, K.; Fletcher, J.P.; Medbury, H.J. Human classical monocytes display unbalanced M1/M2 phenotype with increased atherosclerotic risk and presence of disease. Int. Angiol. 2017, 36, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.A.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Varma, C.; Shantsila, E. Impact of Mon2 monocyte-platelet aggregates on human coronary artery disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eligini, S.; Cosentino, N.; Fiorelli, S.; Fabbiocchi, F.; Niccoli, G.; Refaat, H.; Camera, M.; Calligaris, G.; De Martini, S.; Bonomi, A.; et al. Biological profile of monocyte-derived macrophages in coronary heart disease patients: Implications for plaque morphology. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.C.; Lee, W.J.; Chen, C.Y.; Lee, B.C. Intermediate CD14(++)CD16(+) monocyte predicts severe coronary stenosis and extensive plaque involvement in asymptomatic individuals. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 33, 1223–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zungsontiporn, N.; Tello, R.R.; Zhang, G.; Mitchell, B.I.; Budoff, M.; Kallianpur, K.J.; Nakamoto, B.K.; Keating, S.M.; Norris, P.J.; Ndhlovu, L.C.; et al. Non-Classical Monocytes and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1) Correlate with Coronary Artery Calcium Progression in Chronically HIV-1 Infected Adults on Stable Antiretroviral Therapy. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.K.; Williams, H.; Li, S.C.H.; Fletcher, J.P.; Medbury, H.J. Monocyte inflammatory profile is specific for individuals and associated with altered blood lipid levels. Atherosclerosis 2017, 263, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, K.L.; Tai, J.J.; Wong, W.C.; Han, H.; Sem, X.; Yeap, W.H.; Kourilsky, P.; Wong, S.C. Gene expression profiling reveals the defining features of the classical, intermediate, and nonclassical human monocyte subsets. Blood 2011, 118, e16–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marimuthu, R.; Francis, H.; Dervish, S.; Li, S.C.H.; Medbury, H.; Williams, H. Characterization of Human Monocyte Subsets by Whole Blood Flow Cytometry Analysis. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 140, 57941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chan, S.H.; Hung, C.H.; Shih, J.Y.; Chu, P.M.; Cheng, Y.H.; Lin, H.C.; Tsai, K.L. SIRT1 inhibition causes oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease. Redox. Biol. 2017, 13, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, A.; De Servi, S.; Mazzucchelli, I.; Fossati, G.; Gritti, D.; Canale, C.; Cusa, C.; Ricevuti, G. Increased expression of CD11b/CD18 on phagocytes in ischaemic disease: A bridge between inflammation and coagulation. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 27, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassirer, M.; Zeltser, D.; Prochorov, V.; Schoenman, G.; Frimerman, A.; Keren, G.; Shapira, I.; Miller, H.; Roth, A.; Arber, N.; et al. Increased expression of the CD11b/CD18 antigen on the surface of peripheral white blood cells in patients with ischemic heart disease: Further evidence for smoldering inflammation in patients with atherosclerosis. Am. Heart J. 1999, 138, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, M.; Imanishi, T.; Ozaki, Y.; Satogami, K.; Masuno, T.; Wada, T.; Nakatani, Y.; Ishibashi, K.; Komukai, K.; Tanimoto, T.; et al. Differential expression of Toll-like receptor 4 and human monocyte subsets in acute myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis 2012, 221, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapp, L.D.; Shantsila, E.; Wrigley, B.J.; Montoro-Garcia, S.; Lip, G.Y. TLR4 expression on monocyte subsets in myocardial infarction. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 273, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fadini, G.P.; de Kreutzenberg, S.V.; Boscaro, E.; Albiero, M.; Cappellari, R.; Krankel, N.; Landmesser, U.; Toniolo, A.; Bolego, C.; Cignarella, A.; et al. An unbalanced monocyte polarisation in peripheral blood and bone marrow of patients with type 2 diabetes has an impact on microangiopathy. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 1856–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Satoh, N.; Shimatsu, A.; Himeno, A.; Sasaki, Y.; Yamakage, H.; Yamada, K.; Suganami, T.; Ogawa, Y. Unbalanced M1/M2 phenotype of peripheral blood monocytes in obese diabetic patients: Effect of pioglitazone. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krychtiuk, K.A.; Kastl, S.P.; Hofbauer, S.L.; Wonnerth, A.; Goliasch, G.; Ozsvar-Kozma, M.; Katsaros, K.M.; Maurer, G.; Huber, K.; Dostal, E.; et al. Monocyte subset distribution in patients with stable atherosclerosis and elevated levels of lipoprotein(a). J. Clin. Lipidol. 2015, 9, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krychtiuk, K.A.; Kastl, S.P.; Pfaffenberger, S.; Lenz, M.; Hofbauer, S.L.; Wonnerth, A.; Koller, L.; Katsaros, K.M.; Pongratz, T.; Goliasch, G.; et al. Association of small dense LDL serum levels and circulating monocyte subsets in stable coronary artery disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Z.S.; Chiang, B.L. Correlation between serum lipid profiles and the ratio and count of the CD16+ monocyte subset in peripheral blood of apparently healthy adults. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2002, 101, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rogacev, K.S.; Zawada, A.M.; Emrich, I.; Seiler, S.; Bohm, M.; Fliser, D.; Woollard, K.J.; Heine, G.H. Lower Apo A-I and lower HDL-C levels are associated with higher intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocyte counts that predict cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 2120–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yvan-Charvet, L.; Pagler, T.; Gautier, E.L.; Avagyan, S.; Siry, R.L.; Han, S.; Welch, C.L.; Wang, N.; Randolph, G.J.; Snoeck, H.W.; et al. ATP-binding cassette transporters and HDL suppress hematopoietic stem cell proliferation. Science 2010, 328, 1689–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murphy, A.J.; Akhtari, M.; Tolani, S.; Pagler, T.; Bijl, N.; Kuo, C.L.; Wang, M.; Sanson, M.; Abramowicz, S.; Welch, C.; et al. ApoE regulates hematopoietic stem cell proliferation, monocytosis, and monocyte accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4138–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiang, Y.; Liang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, F. Lower HDL-C levels are associated with higher expressions of CD16 on monocyte subsets in coronary atherosclerosis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 2171–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krychtiuk, K.A.; Kastl, S.P.; Pfaffenberger, S.; Pongratz, T.; Hofbauer, S.L.; Wonnerth, A.; Katsaros, K.M.; Goliasch, G.; Gaspar, L.; Huber, K.; et al. Small high-density lipoprotein is associated with monocyte subsets in stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2014, 237, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dai Perrard, X.Y.; Lian, Z.; Bobotas, G.; Dicklin, M.R.; Maki, K.C.; Wu, H. Effects of n-3 fatty acid treatment on monocyte phenotypes in humans with hypertriglyceridemia. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2017, 11, 1361–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, S.; Jialal, I. Validation of the circulating monocyte being representative of the cholesterol-loaded macrophage: Biomediator activity. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2008, 132, 1432–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongkind, J.F.; Verkerk, A.; Hoogerbrugge, N. Monocytes from patients with combined hypercholesterolemia-hypertriglyceridemia and isolated hypercholesterolemia show an increased adhesion to endothelial cells in vitro: II. Influence of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on monocyte binding. Metabolism 1995, 44, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, R.M.; Wu, H.; Foster, G.A.; Devaraj, S.; Jialal, I.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Knowlton, A.A.; Simon, S.I. CD11c/CD18 expression is upregulated on blood monocytes during hypertriglyceridemia and enhances adhesion to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Short, J.D.; Tavakoli, S.; Nguyen, H.N.; Carrera, A.; Farnen, C.; Cox, L.A.; Asmis, R. Dyslipidemic Diet-Induced Monocyte “Priming” and Dysfunction in Non-Human Primates Is Triggered by Elevated Plasma Cholesterol and Accompanied by Altered Histone Acetylation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.-F.; Chang, Y.-H.; Chien, S.-C.; Lin, Y.-H.; Yeh, H.-Y. Epidemiology of Dyslipidemia in the Asia Pacific Region. Int. J. Gerontol. 2018, 12, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Jonas, J.B.; You, Q.S.; Wang, Y.X.; Yang, H. Prevalence and associated factors of dyslipidemia in the adult Chinese population. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Talpur, M.T.H.; Katbar, M.T.; Shabir, K.U.; Shabir, K.U.; Yaqoob, U.; Jabeen, S.; Zia, D. Prevalence of dyslipidemia in young adults. Prof. Med. J. 2020, 27, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foldes, G.; von Haehling, S.; Okonko, D.O.; Jankowska, E.A.; Poole-Wilson, P.A.; Anker, S.D. Fluvastatin reduces increased blood monocyte Toll-like receptor 4 expression in whole blood from patients with chronic heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2008, 124, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadini, G.P.; Simoni, F.; Cappellari, R.; Vitturi, N.; Galasso, S.; Vigili de Kreutzenberg, S.; Previato, L.; Avogaro, A. Pro-inflammatory monocyte-macrophage polarization imbalance in human hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2014, 237, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, K.; Vengrenyuk, Y.; Ramsey, S.A.; Vila, N.R.; Girgis, N.M.; Liu, J.; Gusarova, V.; Gromada, J.; Weinstock, A.; Moore, K.J.; et al. Inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes and their conversion to M2 macrophages drive atherosclerosis regression. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2904–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursill, C.A.; Castro, M.L.; Beattie, D.T.; Nakhla, S.; van der Vorst, E.; Heather, A.K.; Barter, P.J.; Rye, K.A. High-density lipoproteins suppress chemokines and chemokine receptors in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, A.J.; Barrett, T.J.; Taylor, L.; McNeill, E.; Manmadhan, A.; Recio, C.; Carmineri, A.; Brodermann, M.H.; White, G.E.; Cooper, D.; et al. Acute exposure to apolipoprotein A1 inhibits macrophage chemotaxis in vitro and monocyte recruitment in vivo. Elife 2016, 5, e15190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacke, F.; Alvarez, D.; Kaplan, T.J.; Jakubzick, C.; Spanbroek, R.; Llodra, J.; Garin, A.; Liu, J.; Mack, M.; van Rooijen, N.; et al. Monocyte subsets differentially employ CCR2, CCR5, and CX3CR1 to accumulate within atherosclerotic plaques. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Han, K.H.; Han, K.O.; Green, S.R.; Quehenberger, O. Expression of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 is increased in hypercholesterolemia. Differential effects of plasma lipoproteins on monocyte function. J. Lipid Res. 1999, 40, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okopien, B.; Huzarska, M.; Kulach, A.; Stachura-Kulach, A.; Madej, A.; Belowski, D.; Zielinski, M.; Herman, Z.S. Hypolipidemic drugs affect monocyte IL-1beta gene expression and release in patients with IIa and IIb dyslipidemia. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2005, 45, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okopien, B.; Kowalski, J.; Krysiak, R.; Labuzek, K.; Stachura-Kulach, A.; Kulach, A.; Zielinski, M.; Herman, Z.S. Monocyte suppressing action of fenofibrate. Pharmacol. Rep. 2005, 57, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okopien, B.; Krysiak, R.; Haberka, M.; Herman, Z.S. Effect of monthly atorvastatin and fenofibrate treatment on monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 release in patients with primary mixed dyslipidemia. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2005, 45, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okopien, B.; Krysiak, R.; Kowalski, J.; Madej, A.; Belowski, D.; Zielinski, M.; Herman, Z.S. Monocyte release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta in primary type IIa and IIb dyslipidemic patients treated with statins or fibrates. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2005, 46, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C.V., Jr.; Pesaro, A.E.; de Lemos, J.A.; Rached, F.; Segre, C.A.; Gomes, F.; Ribeiro, A.F.; Nicolau, J.C.; Yoshida, V.M.; Monteiro, H.P. Native LDL-cholesterol mediated monocyte adhesion molecule overexpression is blocked by simvastatin. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2009, 23, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysiak, R.; Okopien, B. Different effects of simvastatin on ex vivo monocyte cytokine release in patients with hypercholesterolemia and impaired glucose tolerance. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 61, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krysiak, R.; Stachura-Kulach, A.; Okopien, B. Metabolic and monocyte-suppressing actions of fenofibrate in patients with mixed dyslipidemia and early glucose metabolism disturbances. Pharmacol. Rep. 2010, 62, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysiak, R.; Okopien, B. The effect of ezetimibe and simvastatin on monocyte cytokine release in patients with isolated hypercholesterolemia. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2011, 57, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysiak, R.; Okopien, B. Effect of bezafibrate on monocyte cytokine release and systemic inflammation in patients with impaired fasting glucose. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 51, 1459–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkering, S.; Stiekema, L.C.A.; Bernelot Moens, S.; Verweij, S.L.; Novakovic, B.; Prange, K.; Versloot, M.; Roeters van Lennep, J.E.; Stunnenberg, H.; de Winther, M.; et al. Treatment with Statins Does Not Revert Trained Immunity in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.A.; London, E. Structure and function of sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 17221–17224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stout, R.D.; Jiang, C.; Matta, B.; Tietzel, I.; Watkins, S.K.; Suttles, J. Macrophages sequentially change their functional phenotype in response to changes in microenvironmental influences. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfs, I.M.; Donners, M.M.; de Winther, M.P. Differentiation factors and cytokines in the atherosclerotic plaque micro-environment as a trigger for macrophage polarisation. Thromb. Haemost. 2011, 106, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Quintin, J.; Kerstens, H.H.D.; Rao, N.A.; Aghajanirefah, A.; Matarese, F.; Cheng, S.-C.; Ratter, J.; Berentsen, K.; van der Ent, M.A.; et al. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science 2014, 345, 1251086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arts, R.J.; Novakovic, B.; Ter Horst, R.; Carvalho, A.; Bekkering, S.; Lachmandas, E.; Rodrigues, F.; Silvestre, R.; Cheng, S.C.; Wang, S.Y.; et al. Glutaminolysis and Fumarate Accumulation Integrate Immunometabolic and Epigenetic Programs in Trained Immunity. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bories, G.; Caiazzo, R.; Derudas, B.; Copin, C.; Raverdy, V.; Pigeyre, M.; Pattou, F.; Staels, B.; Chinetti-Gbaguidi, G. Impaired alternative macrophage differentiation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from obese subjects. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 2012, 9, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Al-Sharea, A.; Lee, M.K.; Moore, X.L.; Fang, L.; Sviridov, D.; Chin-Dusting, J.; Andrews, K.L.; Murphy, A.J. Native LDL promotes differentiation of human monocytes to macrophages with an inflammatory phenotype. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 115, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Moore, X.L.; Fu, Y.; Al-Sharea, A.; Dragoljevic, D.; Fernandez-Rojo, M.A.; Parton, R.; Sviridov, D.; Murphy, A.J.; Chin-Dusting, J.P. High-density lipoprotein inhibits human M1 macrophage polarization through redistribution of caveolin-1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murphy, A.J.; Woollard, K.J.; Hoang, A.; Mukhamedova, N.; Stirzaker, R.A.; McCormick, S.P.; Remaley, A.T.; Sviridov, D.; Chin-Dusting, J. High-density lipoprotein reduces the human monocyte inflammatory response. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 2071–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bekkering, S.; van den Munckhof, I.; Nielen, T.; Lamfers, E.; Dinarello, C.; Rutten, J.; de Graaf, J.; Joosten, L.A.; Netea, M.G.; Gomes, M.E.; et al. Innate immune cell activation and epigenetic remodeling in symptomatic and asymptomatic atherosclerosis in humans in vivo. Atherosclerosis 2016, 254, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bekkering, S.; Quintin, J.; Joosten, L.A.; van der Meer, J.W.; Netea, M.G.; Riksen, N.P. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 1731–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, S.T.; Groh, L.; Thiem, K.; Bekkering, S.; Li, Y.; Matzaraki, V.; van der Heijden, C.; van Puffelen, J.H.; Lachmandas, E.; Jansen, T.; et al. Rewiring of glucose metabolism defines trained immunity induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 98, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valk, F.M.v.d.; Bekkering, S.; Kroon, J.; Yeang, C.; Bossche, J.V.d.; Buul, J.D.v.; Ravandi, A.; Nederveen, A.J.; Verberne, H.J.; Scipione, C.; et al. Oxidized Phospholipids on Lipoprotein(a) Elicit Arterial Wall Inflammation and an Inflammatory Monocyte Response in Humans. Circulation 2016, 134, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyszczyk, P.; Schloss, R.; Palmer, A.; Berthiaume, F. The Role of Macrophages in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing and Interventions to Promote Pro-wound Healing Phenotypes. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bossche, J.; Baardman, J.; Otto, N.A.; van der Velden, S.; Neele, A.E.; van den Berg, S.M.; Luque-Martin, R.; Chen, H.J.; Boshuizen, M.C.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Prevents Repolarization of Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishiga, M.; Wang, D.W.; Han, Y.; Lewis, D.B.; Wu, J.C. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: From basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, X.; Liu, X.; Guan, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H.; Qian, J.; Wang, Z.; Lin, X. Dynamic changes in monocytes subsets in COVID-19 patients. Hum. Immunol. 2021, 82, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masana, L.; Correig, E.; Ibarretxe, D.; Anoro, E.; Arroyo, J.A.; Jerico, C.; Guerrero, C.; Miret, M.; Naf, S.; Pardo, A.; et al. Low HDL and high triglycerides predict COVID-19 severity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feingold, K.R. The bidirectional link between HDL and COVID-19 infections. J. Lipid Res. 2021, 62, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Patient Population | N= | Classical (CM%) | Intermediate (IM%) | Nonclassical (NCM%) | Other Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tallone [31] | CAD (Stable) | 13 | 82 (↓) * | 3.6(=) | 9.2(↑) * | Additionally reported a fourth population, “CD14-CD16+” but not significantly different between groups |

| Control | 14 | 87 | 3.3 | 5.8 | ||

| Dopheide [32] | PAD (CLI) | 60 | 66.2 (↓) *** | 10.6(↑) *** | 15 (=) | |

| PAD (IC) | 74.4 (↓) * | 10.5 (↑) *** | 23.3 (↑) *** | |||

| Control | 30 | 82 | 6 | 11.9 | ||

| Ozaki [24] | CAD (multi vessel) | 51 | Not stated | 25.5 (↑) *** | Not stated | |

| CAD (one vessel) | 47 | Not stated | 12.5(↑) ** | Not stated | ||

| Control | 27 | Not stated | 8.5 | Not stated | ||

| Tapp [33] | CAD (Stable) | 40 | 82 (=) | 6.9 (=) | 10.8 (=) | Additionally included data on STEMI, ↑ IM% and ↓ NCM% vs. control and CAD |

| Control | 40 | 83 | 6.4 | 10.6 | ||

| Shantsila [20] | CAD (Stable) | 53 | 85 (=) | 5.4 (=) | 9.8 (=) | Proportions calculated from subset counts |

| Control | 50 | 84 | 5.8 | 9.8 | ||

| Sturhan [34] | CAD (Stable) | 80 | 82 (↓) * | 13 (↑) * | 5 (↑) * | Additionally included data for acute MI, which showed the same changes as CAD vs. control but no difference from CAD group |

| Control | 34 | 90 | 7 | 3 | ||

| Shirai [35] | CAD | 69 (↓) ** | 20 (↑) ** | 3.5(=) | ||

| Control | 83 | 7 | 4 | |||

| Zhuang [36] | Unstable angina | 48 | 82(=) | 10.6 (↑) * | 6.97(↓) * | Additionally presented data on STEMI, which showed elevated IM% and lower NCM% vs. controls (p < 0.05) |

| Control | 33 | 82 | 7.4 | 10.3 | ||

| Williams [37] | CVD (carotid endarterectomy and/or PAD) | 31 | ~88(=) | ~5(↑)* | ~6(=) | Proportions estimated from graph |

| Control | 33 | ~90 | ~4 | ~5 | ||

| Brown [38] | Diffuse CAD | 50 | 84.5(=) | 7.2(=) | 8.3 (=) | Control had CAD risk factors, as opposed to “healthy control” group |

| Focal CAD | 40 | 85.2(=) | 6.2(=) | 8.6(=) | ||

| Control | 50 | 87.1 | 5.1 | 7.8 | ||

| Eligini [39] | CAD | 90 | 85.8(=) | 10.5 (↑) *** | 3.7(=) | |

| Control | 25 | 85.1 | 7.6 | 4.6 |

| Reference | Clinical Model | N= | Monocyte Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mazzone [46] | CAD | 120 | CD11b/CD18 was higher on patients with CAD and PAD compared to controls |

| PAD | 50 | ||

| Control | 200 | ||

| Kassirer [47] | Ischemic heart disease | 45 | CD11b/CD18 was higher on patients with ischemic heart disease than controls |

| Control | 66 | ||

| Tallone [31] | CAD (Stable) | 13 | Higher CCR2 and CX3CR1 on classical monocytes in CAD vs. control |

| Control | 14 | ||

| Shantsila [20] | CAD (Stable) | 53 | Upregulated IL-6 on CM and IM in CAD. TNFα production of LPS-stimulated monocytes over baseline was lower in CAD patients than controls |

| Control | 50 | ||

| Shirai [35] | CAD | 7 | Higher gene expression of IL-6 and IL-1β in response to LPS/Interferon(IFN)γ |

| Control | 7 | ||

| Williams [37] | CVD patients | 31 | CD163(M2) lower in CVD, CD86/CD163(M1/M2) ratio higher in CVD |

| Control | 33 | ||

| Chan [45] | CAD (Stable) | 30 | Increased NF-κb activity and iNOS expression in CAD |

| Control | 30 | Increased monocyte adhesion to human endothelial cells |

| Reference | Clinical Model | N= | Monocyte Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Huang [54] | Healthy individuals | 100 | Inverse association between HDL-C and combined IM +NCM count 1 |

| Rogacev [55] | Chronic kidney disease (CKD) | 438 | ApoA1 and HDL-C inversely correlated with IM counts |

| Krychtiuk [59] | Stable CAD | 90 | Small HDL correlated with NCM% and inversely with CM% Highest tertile of small HDL had increased NCM% and decreased CM% compared with the two lower tertiles |

| Krychtiuk [52] | Stable CAD | 90 | Elevated Lp(a) (>50 mg/dL) was associated with increased IM% OxPL/ApoB 2 correlated with IM% |

| Krychtiuk [53] | Stable CAD | 90 | Top tertile sdLDL had highest NCM% and lower CM% than the two lower tertiles |

| Treatment model | |||

| Dai Perrad [60] 3 | Hypertriglyceridemia | 27 | Triglyceride lowering treatment with Omega-3 fatty acids MAT9001 or EPA-EE decreased IM% and count, and increased the CM% and count. EPA-EE slightly, but significantly, decreased NCM% |

| Reference | Clinical Model | N= | Monocyte Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jongkind 1 [62] | Familial hypercholesterolemia | 28 | All four patient groups showed increased monocyte binding to cultured endothelial cells compared to the controls |

| Polygenic hypercholesterolemia | 10 | ||

| Familial combined hyperlipidemia | 17 | ||

| Non familial combined Hypercholesterolemia/Hypertriglyceridemia | 17 | ||

| Healthy controls | 18 | ||

| Devaraj [61] | Hyperlipidemic patients 2 | 16 | Monocyte superoxide anion release, IL-1, TNF, IL-6, CD14, CD11b and adhesion to human endothelium were significantly increased in patients compared with controls |

| Healthy controls | 16 | ||

| Foldes [69] | Chronic heart failure | 26 | Monocyte TLR4 expression was inversely associated with total cholesterol, HDL, ApoA1 3 |

| Healthy controls | 13 | ||

| Fadini 4 [70] | Familial hypercholesterolemia | 22 | Across the three groups, for those not receiving treatment, LDL correlated with the percentage of M1 monocytes and M1/M2 ratio. For those receiving treatment a milder correlation between LDL-C and M1/M2 ratio |

| Non familial hypercholesterolemia | 20 | ||

| Healthy controls | 20 | ||

| Williams [37] | CVD patients (21) Peripheral arterial disease (10) | 31 | In controls: ApoA1 correlated with CD163 and inversely with CD86/CD163 on classical monocytes and HDL inversely correlated with CD86/CD163 on classical monocytes |

| Healthy controls | 33 | ||

| Patel [42] | Healthy controls and generally healthy dyslipidemic individuals | 30 | For all monocyte subsets: HDL-C inversely correlated with IL-1β, CD86, TNFR2, CD319. ApoA1 inversely correlated with IL-1β, TNFR2. Total cholesterol and LDL-C correlated with TLR2, CD163. ApoB correlated with TLR2, CD163, CD93 Other associations for one or two monocyte subsets were observed |

| Patel [23] | Healthy controls and generally healthy dyslipidemic individuals | 30 | For all monocyte subsets: ApoA1 inversely correlated with CD62L, CD11b, CD11c and CD29. Other associations (between recruitment markers and ApoA1) for one or two monocyte subsets were observed |

| Diet models | |||

| Gower [63] | High fat feeding of healthy females | Fasted state: Monocyte CD11c correlated with Triglycerides, ApoB, total cholesterol/HDL ratio, Non-HDL-C, total cholesterol and LDL-C After feeding5: Monocyte CD11c expression and arrest on VCAM-1 was elevated—peaking with hypertriglyceridemia, before returning to fasting levels. Monocyte CD11c correlated with triglycerides, Non-HDL-C, ApoB, total cholesterol/HDL ratio, total cholesterol | |

| Short [64] | Male baboons fed a Western diet 6 | 13 | After feeding: Monocyte chemotaxis and MKP-1 activity correlated with cholesterol |

| Reference | Clinical Model | N= | Treatment (n) | Monocyte Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Han [75] | Hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women | 48 | Both groups: Estrogen | At baseline: Monocyte CCR2 gene expression was significantly elevated in individuals with high LDL-C and low HDL-C, compared to individuals with low LDL-C and low HDL-C. There was a significant correlation between CCR2 gene expression and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios. Upon treatment: Estrogen supplement therapy reduced CCR2 gene expression in hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women but not normocholesterolemic subjects. There was a correlation between the changes in the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio and the changes in monocyte CCR2 gene expression. |

| Postmenopausal women (normal cholesterol) | ||||

| Okopien [76] | Type 11a dyslipidemia | 12 | Atorvastatin | At baseline: Monocyte IL-1β secretion was elevated in both patient groups compared with the controls. Upon treatment: Atorvastatin and Fenofibrate both reduced monocyte IL-1β release and mRNA expression of IL-1β compared to pretreatment. |

| Type 11b dyslipidemia | 12 | Fenofibrate | ||

| Healthy controls | 13 | |||

| Okopien [77] | Type 11b dyslipidemia | 14 | Fenofibrate | At baseline: Monocyte IL-1β, IL-6 and Monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 levels were higher in hyperlipidemic patients compared to controls. Upon treatment: The level of IL-1β, IL-6 and MCP-1 were decreased compared to pre-treatment. |

| Healthy controls | 12 | |||

| Okopien [78] | Atherosclerosis patients with mixed dyslipidemia | 52 | Atorvastatin, Fenofibrate or Placebo | At baseline: Dyslipidemic patients exhibited increased monocyte MCP-1 release compared to control subjects. Upon treatment: Atorvastatin and fenofibrate decreased monocyte MCP-1 secretion compared to pretreatment. However, the reduction was not related to the degree of lipid profile improvement. |

| Controls 1 | 16 | |||

| Okopien [79] | Type IIa dyslipidemic patients | 83 | Fluvastatin (33), Simvastatin (30) or untreated (20) | At baseline: Monocyte secretion of IL-1β was greater from the Type IIa dyslipidemic patients than Type IIb and controls. TNFα release was significantly greater for both patient groups than age matched controls. TNFα release correlated with total cholesterol and ApoB, and IL-1β release positively correlated with total cholesterol, LDL-C and ApoB. Upon treatment: Both statins and ciprofibrate reduced monocyte release of TNFα and IL-1β compared with pretreatment. Fenofibrate only reduced TNFα compared with pretreatment. TNFα and IL-1β levels after treatment were not different than controls. |

| Type IIb dsylipidemic patients | 86 | Ciprofibrate (34), Fenofibrate (34) or untreated (18) | ||

| Controls 1 | 59 | |||

| Serrano [80] | Hypercholesterolemia 2 with stable coronary artery disease | 23 | Simvastatin | At baseline: Patients’ monocytes had higher levels of CD11b, CD14 and lower L-selectin expression compared with monocytes from control individuals. Upon treatment: Statin therapy downregulated CD11b and CD14 whilst increasing L-selectin expression in patients to levels comparable with healthy controls. |

| Healthy controls | 15 | |||

| Krysiak [81] | Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) | 26 | Both patient groups: Simvastatin | At baseline: Patients’ monocytes released higher levels of TNFα IL-1β, IL-6 and MCP-1 than controls. Upon treatment: Simvastatin reduced monocyte cytokine secretion in hypercholesterolemia, but not IGT subjects. |

| Hyercholesterolemia 3 | 24 | |||

| Healthy controls | 25 | |||

| Krysiak [82] | Dyslipidemia 4 | 32 | All patient groups: fenofibrate | At baseline: Patients’ monocytes produced larger amounts of both IL-1β and MCP-1 than controls. Upon treatment: For dyslipidemia (alone) and dyslipidemia with IGT, fenofibrate significantly decreased both IL-1β and MCP-1 but IL-1β was still higher than in controls. For dyslipidemia with IFG, fenofibrate significantly decreased both IL-1β and MCP-1 but both were still higher than in controls. |

| Dyslipidemia with impaired fasting glucose (IFG) | 32 | |||

| Dyslipidemia with IGT | 32 | |||

| Healthy controls | 29 | |||

| Krysiak [83] | Hypercholesterolemia 5 | 134 | Ezetimibe (34), | At baseline: Patients’ monocytes released higher levels of TNFα IL-1β, IL-6 and MCP-1 than controls. Upon treatment: Compared with placebo, both Simvastatin treatment options reduced monocyte TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6 and MCP-1. For subjects receiving both medications, the levels matched those of healthy controls after 30 days of treatment. Simvastatin alone was superior to ezetimibe in reducing monocyte cytokine release. A longer treatment (90 vs. 30 days) with simvastatin or simvastatin + ezetimibe was more effective in reducing cytokine release. |

| Simvastatin (33), | ||||

| Ezetimibe + Simvastatin (35) or | ||||

| Placebo (32) | ||||

| Healthy controls | 30 | |||

| Krysiak [84] | IFG | 28 | Both patient groups: Bezafibrate | At baseline: IFG and MD subjects had increased monocyte release of MCP-1, IL-6, TNFα and IL-1β. Upon treatment: Monocyte release of MCP-1, IL-6, TNFα and IL-1β was normalized in MD subjects, but only MCP-1 and IL-6 normalized in IFG subjects. |

| Mixed dyslipidemia (MD) 6 | 29 | |||

| Healthy controls | 24 | |||

| Dai Perrard [60] | Hypertriglyceridemia 7 | 83 | MAT9001 or EPA-EE | Upon treatment: Both treatments reduced CD11c and CD36 on CM and IM. |

| Bekkering [85] | Familial Hypercholesterolemia 8 | 25 | Statin | At baseline: Patients’ monocytes had higher levels of CCR2, CD11b, CD11c and CD29. They also had a higher production of TNFα, IL-6 and IL-1β Upon treatment: CCR2 and CD29 (but not CD11b and CD11c) expression were decreased after statin treatment. Cytokine production remained elevated. |

| Healthy controls | 20 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Williams, H.; Mack, C.D.; Li, S.C.H.; Fletcher, J.P.; Medbury, H.J. Nature versus Number: Monocytes in Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179119

Williams H, Mack CD, Li SCH, Fletcher JP, Medbury HJ. Nature versus Number: Monocytes in Cardiovascular Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(17):9119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179119

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilliams, Helen, Corinne D. Mack, Stephen C. H. Li, John P. Fletcher, and Heather J. Medbury. 2021. "Nature versus Number: Monocytes in Cardiovascular Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 17: 9119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179119