Involvement of Rare Mutations of SCN9A, DPP4, ABCA13, and SYT14 in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Family 1

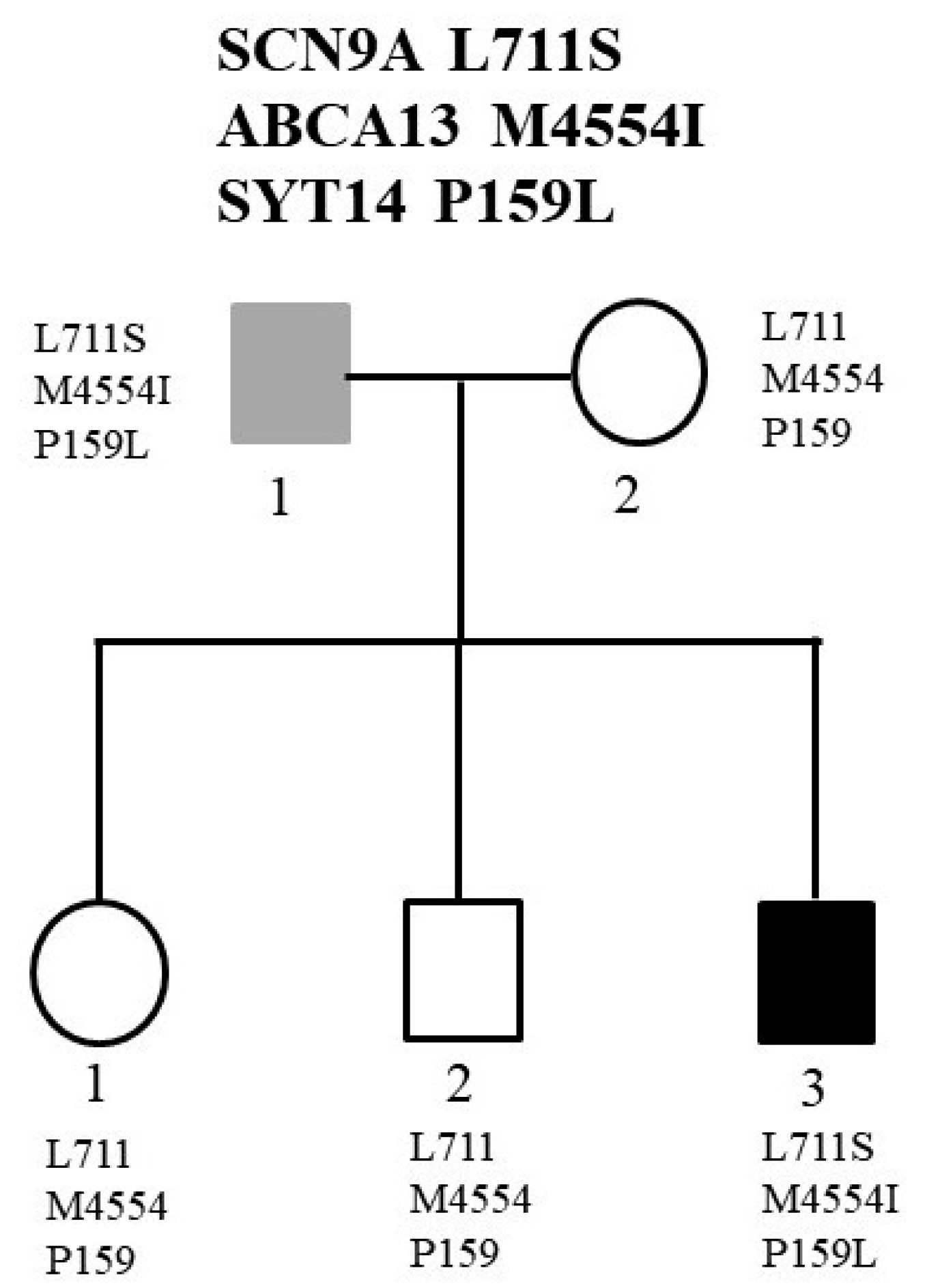

2.2. Family 2

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

4.2. Karyotyping and Chromosomal Microarray Analysis

4.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) Analysis

4.4. Sanger Sequencing

4.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gordovez, F.J.A.; McMahon, F.J. The genetics of bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giegling, I.; Hosak, L.; Mossner, R.; Serretti, A.; Bellivier, F.; Claes, S.; Collier, D.A.; Corrales, A.; DeLisi, L.E.; Gallo, C.; et al. Genetics of schizophrenia: A consensus paper of the WFSBP Task Force on Genetics. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 18, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlar, A.V.; Mercer, K.B.; Zwick, M.E.; Mulle, J.G. New discoveries in schizophrenia genetics reveal neurobiological pathways: A review of recent findings. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 58, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nakamura, T.; Nakajima, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Itohara, S.; Kasahara, T.; Tsuboi, T.; Kato, T. Functional and behavioral effects of de novo mutations in calcium-related genes in patients with bipolar disorder. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, 1851–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, C.; Serretti, A. Role of 108 schizophrenia-associated loci in modulating psychopathological dimensions in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2017, 174, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coryell, W.; Leon, A.C.; Turvey, C.; Akiskal, H.S.; Mueller, T.; Endicott, J. The significance of psychotic features in manic episodes: A report from the NIMH collaborative study. J. Affect. Disord. 2001, 67, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: A genome-wide analysis. Lancet 2013, 381, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Genomic Relationships, Novel Loci, and Pleiotropic Mechanisms across Eight Psychiatric Disorders. Cell 2019, 179, 1469–1482.e1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.; Cao, H.; Baranova, A.; Huang, H.; Li, S.; Cai, L.; Rao, S.; Dai, M.; Xie, M.; Dou, Y.; et al. Multi-trait analysis for genome-wide association study of five psychiatric disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, D.H.; Thiagarajah, T.; Malloy, P.; Pickard, B.S.; Muir, W.J. Chromosome abnormalities, mental retardation and the search for genes in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neurotox. Res. 2008, 14, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.L.; Herrera, L.; Gaspar, P.A.; Nieto, R.; Maturana, A.; Villar, M.J.; Salinas, V.; Silva, H. Shifting the focus toward rare variants in schizophrenia to close the gap from genotype to phenotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2017, 174, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerner, B. Toward a Deeper Understanding of the Genetics of Bipolar Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scionti, F.; Di Martino, M.T.; Pensabene, L.; Bruni, V.; Concolino, D. The Cytoscan HD Array in the Diagnosis of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. High. Throughput 2018, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muzzey, D.; Evans, E.A.; Lieber, C. Understanding the Basics of NGS: From Mechanism to Variant Calling. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2015, 3, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wijsman, E.M. The role of large pedigrees in an era of high-throughput sequencing. Hum. Genet. 2012, 131, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drissi, I.; Woods, W.A.; Woods, C.G. Understanding the genetic basis of congenital insensitivity to pain. Br. Med. Bull. 2020, 133, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waxman, S.G.; Dib-Hajj, S.D. The Two Sides of NaV1.7: Painful and Painless Channelopathies. Neuron 2019, 101, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hisama, F.M.; Dib-Hajj, S.D.; Waxman, S.G. SCN9A Neuropathic Pain Syndromes. In GeneReviews; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Mirzaa, G., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, J.W.; Guo, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.X.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhai, Q.X. Novel mutations in SCN9A occurring with fever-associated seizures or epilepsy. Seizure 2019, 71, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Xu, L.; Gao, F.; Jiang, P. Variable epilepsy phenotypes associated with heterozygous mutation in the SCN9A gene: Report of two cases. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 39, 1113–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasham, J.; Leslie, J.S.; Harrison, J.W.; Deline, J.; Williams, K.B.; Kuhl, A.; Scott Schwoerer, J.; Cross, H.E.; Crosby, A.H.; Baple, E.L. No association between SCN9A and monogenic human epilepsy disorders. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1009161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, M.; Patowary, A.; Stanaway, I.B.; McCord, E.; Nesbitt, R.R.; Archer, M.; Scheuer, T.; Nickerson, D.; Raskind, W.H.; Wijsman, E.M.; et al. Association of rare missense variants in the second intracellular loop of NaV1.7 sodium channels with familial autism. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Z.; Ye, X.; Qiao, P.; Luo, W.; Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Gao, P. G327E mutation in SCN9A gene causes idiopathic focal epilepsy with Rolandic spikes: A case report of twin sisters. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 1457–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarmolowska, B.; Bukalo, M.; Fiedorowicz, E.; Cieslinska, A.; Kordulewska, N.K.; Moszynska, M.; Swiatecki, A.; Kostyra, E. Role of Milk-Derived Opioid Peptides and Proline Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Nutrients 2019, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frenssen, F.; Croonenberghs, J.; Van den Steene, H.; Maes, M. Prolyl endopeptidase and dipeptidyl peptidase IV are associated with externalizing and aggressive behaviors in normal and autistic adolescents. Life Sci. 2015, 136, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuele, E.; Minoretti, P.; Martinelli, V.; Pesenti, S.; Olivieri, V.; Aldeghi, A.; Politi, P. Circulating levels of soluble CD26 are associated with phobic anxiety in women. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 30, 1334–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Lamb, J.R.; McKeown, A.P.; Miller, S.; Muglia, P.; Guest, P.C.; Bahn, S.; Domenici, E.; Rahmoune, H. Identification of altered dipeptidyl-peptidase activities as potential biomarkers for unipolar depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van West, D.; Monteleone, P.; Di Lieto, A.; De Meester, I.; Durinx, C.; Scharpe, S.; Lin, A.; Maj, M.; Maes, M. Lowered serum dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity in patients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000, 250, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliou, V.; Vasiliou, K.; Nebert, D.W. Human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family. Hum. Genom. 2009, 3, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakato, M.; Shiranaga, N.; Tomioka, M.; Watanabe, H.; Kurisu, J.; Kengaku, M.; Komura, N.; Ando, H.; Kimura, Y.; Kioka, N.; et al. ABCA13 dysfunction associated with psychiatric disorders causes impaired cholesterol trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, H.M.; Pickard, B.S.; Maclean, A.; Malloy, M.P.; Soares, D.C.; McRae, A.F.; Condie, A.; White, A.; Hawkins, W.; McGhee, K.; et al. A cytogenetic abnormality and rare coding variants identify ABCA13 as a candidate gene in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 85, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dwyer, S.; Williams, H.; Jones, I.; Jones, L.; Walters, J.; Craddock, N.; Owen, M.J.; O’Donovan, M.C. Investigation of rare non-synonymous variants at ABCA13 in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 790–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degenhardt, F.; Priebe, L.; Strohmaier, J.; Herms, S.; Hoffmann, P.; Mattheisen, M.; Mossner, R.; Nenadic, I.; Sauer, H.; Rujescu, D.; et al. No evidence for an involvement of copy number variation in ABCA13 in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder. Psychiatr. Genet. 2013, 23, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolfes, A.C.; Dean, C. The diversity of synaptotagmin isoforms. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 63, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, M.R.; Reist, N.E. Synaptotagmin: Mechanisms of an electrostatic switch. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 722, 134834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M. Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel class of synaptotagmin (Syt XIV) conserved from Drosophila to humans. J. Biochem. 2003, 133, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Rivera, F.; Chan, A.; Donovan, D.J.; Gusella, J.F.; Ligon, A.H. Disruption of a synaptotagmin (SYT14) associated with neurodevelopmental abnormalities. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2007, 143A, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, H.; Yoshida, K.; Yasuda, T.; Fukuda, M.; Fukuda, Y.; Morita, H.; Ikeda, S.; Kato, R.; Tsurusaki, Y.; Miyake, N.; et al. Exome sequencing reveals a homozygous SYT14 mutation in adult-onset, autosomal-recessive spinocerebellar ataxia with psychomotor retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerner, B.; Rao, A.R.; Christensen, B.; Dandekar, S.; Yourshaw, M.; Nelson, S.F. Rare Genomic Variants Link Bipolar Disorder with Anxiety Disorders to CREB-Regulated Intracellular Signaling Pathways. Front. Psychiatry 2013, 4, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goes, F.S.; Pirooznia, M.; Parla, J.S.; Kramer, M.; Ghiban, E.; Mavruk, S.; Chen, Y.C.; Monson, E.T.; Willour, V.L.; Karchin, R.; et al. Exome Sequencing of Familial Bipolar Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaser, A.; Forstner, A.J.; Strohmaier, J.; Hecker, J.; Ludwig, K.U.; Sivalingam, S.; Streit, F.; Degenhardt, F.; Witt, S.H.; Reinbold, C.S.; et al. Exome sequencing in large, multiplex bipolar disorder families from Cuba. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ganesh, S.; Ahmed, P.H.; Nadella, R.K.; More, R.P.; Seshadri, M.; Viswanath, B.; Rao, M.; Jain, S.; Consortium, A.; Mukherjee, O. Exome sequencing in families with severe mental illness identifies novel and rare variants in genes implicated in Mendelian neuropsychiatric syndromes. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 73, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- John, J.; Bhattacharyya, U.; Yadav, N.; Kukshal, P.; Bhatia, T.; Nimgaonkar, V.L.; Deshpande, S.N.; Thelma, B.K. Multiple rare inherited variants in a four generation schizophrenia family offer leads for complex mode of disease inheritance. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 216, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Family | Gene and dbSNP | Position of Mutation | Allele Frequency | Functional Prediction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiwan Biobank | ALFA | PROVEAN | PolyPhen-2 | SIFT | |||

| 1 | SCN9A rs765818027 | NC_000002.11:g.167149868C>T NM_002977.3:c.980G>A NM_002977.3:p.Gly327Glu | 0.001648 | 0 | Deleterious | Probably damaging | Damaging |

| 1 | DPP4 rs149643982 | NC_000002.11:g.162865098G>A NM_001935.3:c.1961C>T NM_001935.3:p.Ala654Val | 0.000659 | 0.000156 | Deleterious | Probably damaging | Damaging |

| 2 | SCN9A rs187526567 | NC_000002.11:g.167137045A>G NM_002977.3:c.2132T>C NM_002977.3:p.Leu711Ser | 0.003955 | 0.000068 | Deleterious | Probably damaging | Damaging |

| 2 | ABCA13 rs142532424 | NC_000007.13:g.48556342G>A NM_152701.4:c.13662G>A NM_152701.4:p.Met4554Ile | 0.001978 | 0 | Deleterious | Possibly damaging | Damaging |

| 2 | SYT14 rs77686387 | NC_000001.10:g.210267700C>T NM_153262.3:c.476C>T NM_153262.3:p.Pro159Leu | 0.003652 | 0.000318 | Neutral | Probably damaging | Damaging |

| Gene and SNP | Forward Primer Sequences | Reverse Primer Sequences | Ta | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCN9A rs765818027 | 5′-CACCAGGTACATATGCCATTC -3′ | 5′-TCCTTATTCAATATTGTCCCCC-3′ | 60 °C | 313 |

| DPP4 rs149643982 | 5′-ACCCAGCCTTGCAAAATAGCAG-3′ | 5′-GGAAACTGCGACTCGCTTACCA-3′ | 60 °C | 357 |

| SCN9A rs187526567 | 5′-ATTGGGTGGTGTTCCATAGC-3′ | 5′-GCCTGACTGATTTGTATCTGG-3′ | 60 °C | 275 |

| ABCA13 rs142532424 | 5′-TCAGGGATTCACCCCAAGGTC-3′ | 5′-GATGGCTAGCAACCGGGGCAT-3′ | 60 °C | 241 |

| SYT14 rs77686387 | 5′-GTTGCCATCAATTTTTTGATCCAG-3′ | 5′-CTTGGACTGTTGCTGCAGTGGG-3′ | 60 °C | 264 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-S.; Fang, T.-H. Involvement of Rare Mutations of SCN9A, DPP4, ABCA13, and SYT14 in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413189

Chen C-H, Huang Y-S, Fang T-H. Involvement of Rare Mutations of SCN9A, DPP4, ABCA13, and SYT14 in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(24):13189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413189

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Chia-Hsiang, Yu-Shu Huang, and Ting-Hsuan Fang. 2021. "Involvement of Rare Mutations of SCN9A, DPP4, ABCA13, and SYT14 in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 24: 13189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413189

APA StyleChen, C.-H., Huang, Y.-S., & Fang, T.-H. (2021). Involvement of Rare Mutations of SCN9A, DPP4, ABCA13, and SYT14 in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(24), 13189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413189