Ginseng Sprouts Attenuate Mortality and Systemic Inflammation by Modulating TLR4/NF-κB Signaling in an LPS-Induced Mouse Model of Sepsis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

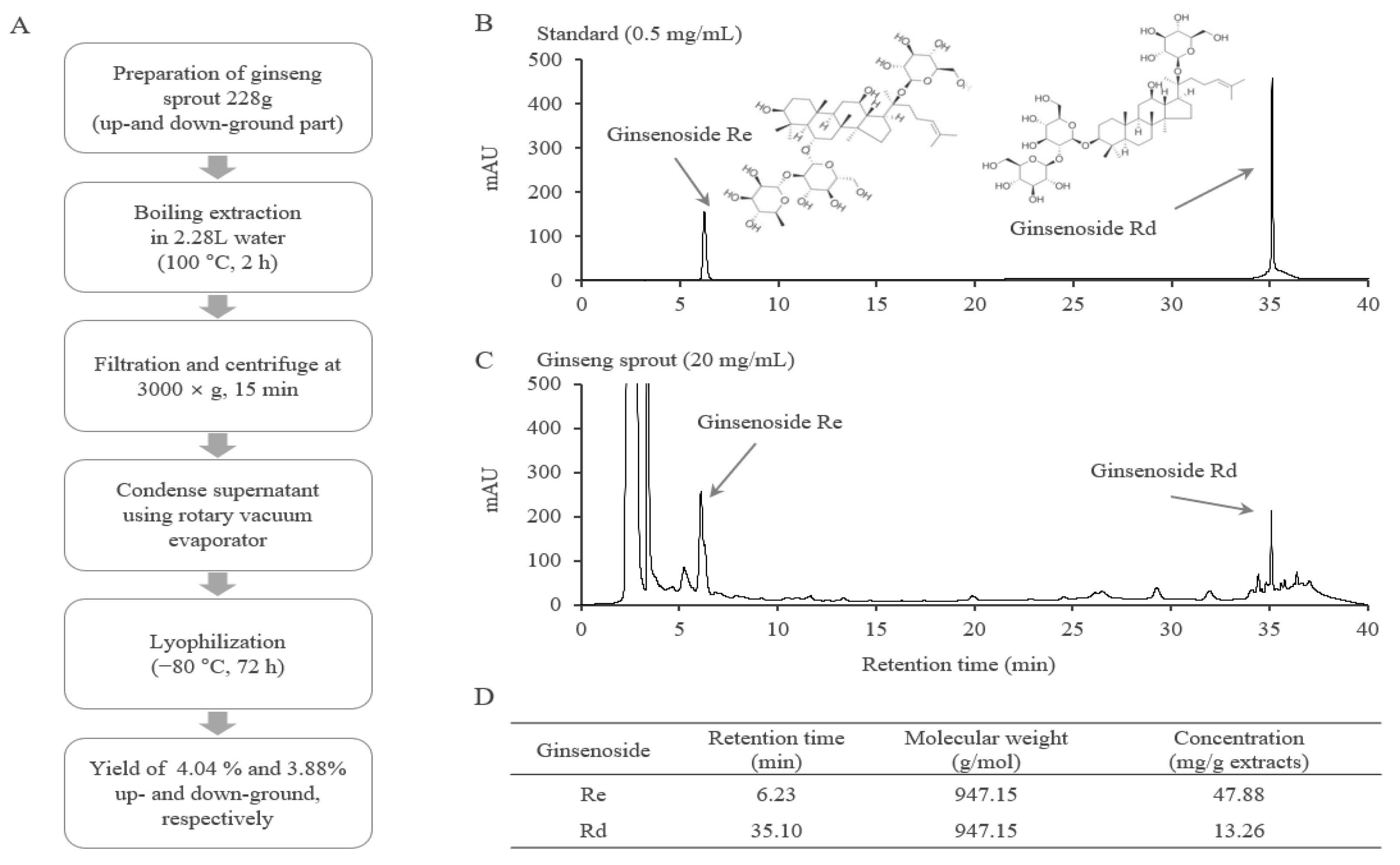

2.1. Fingerprinting Analysis of GSE

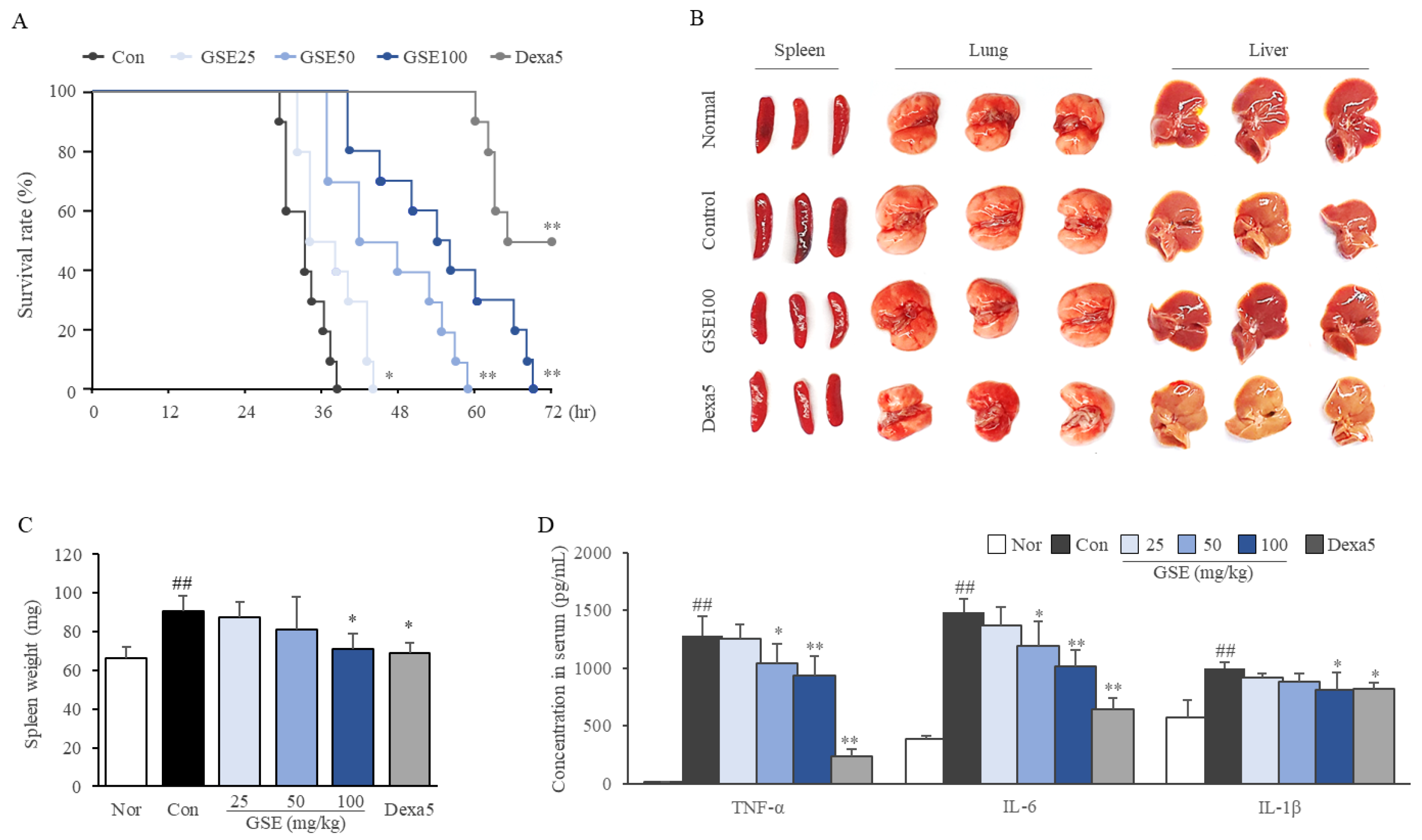

2.2. GSE Delayed the Time to Septic Death

2.3. GSE Ameliorated Systemic Inflammation

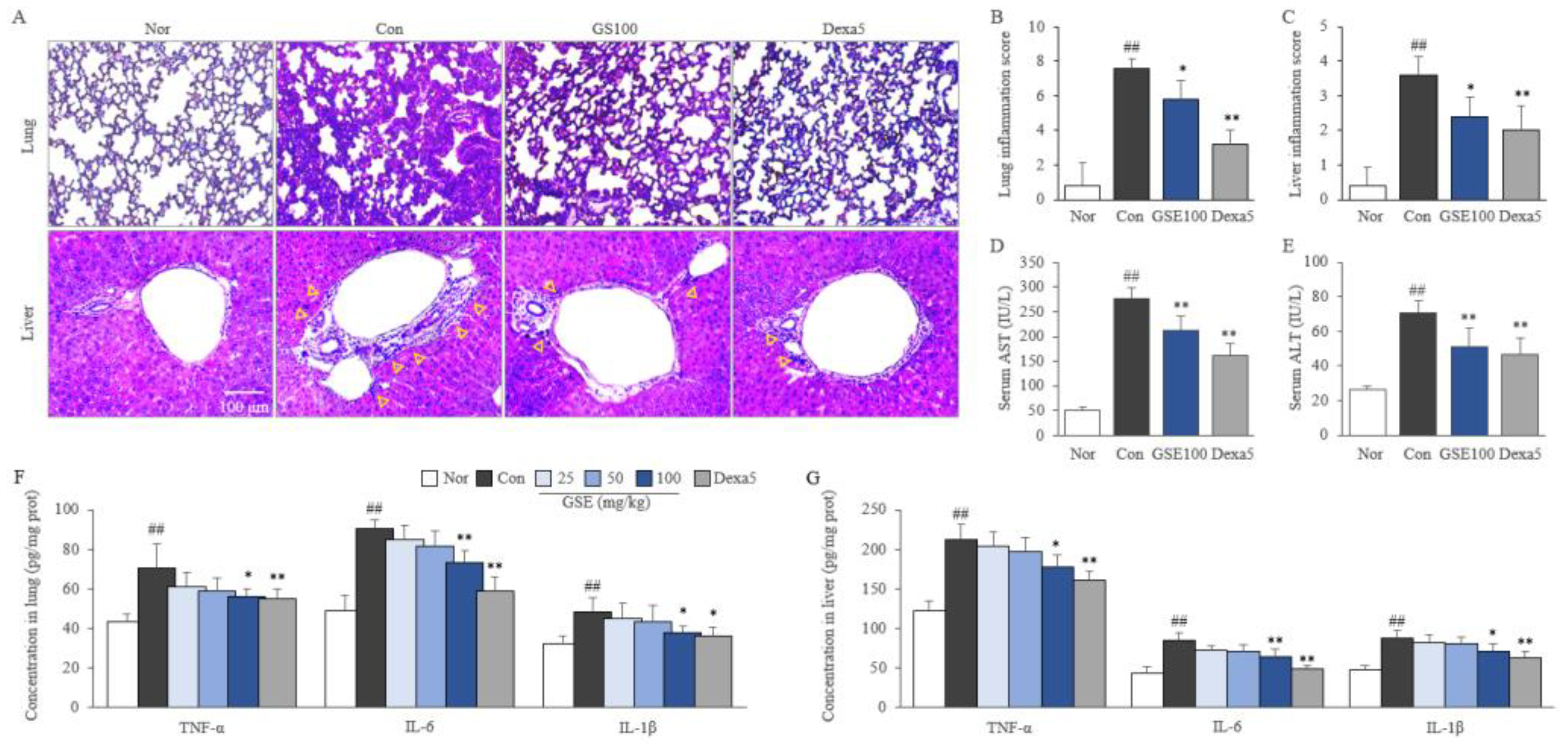

2.4. GSE Attenuated Pulmonary and Hepatic Inflammation

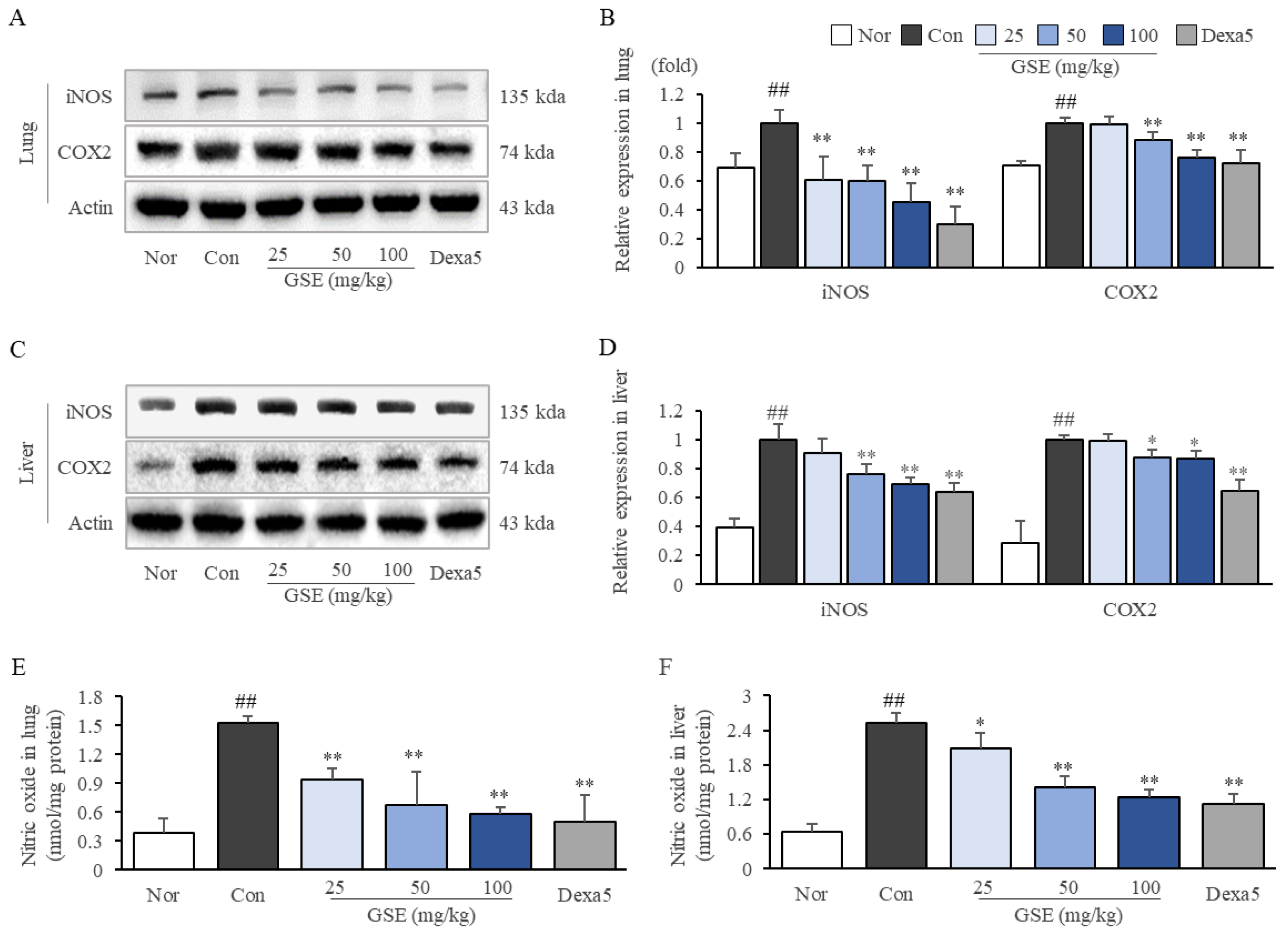

2.5. GSE Suppressed Oxidative-Stress-Related Molecules in Lung and Liver Tissues

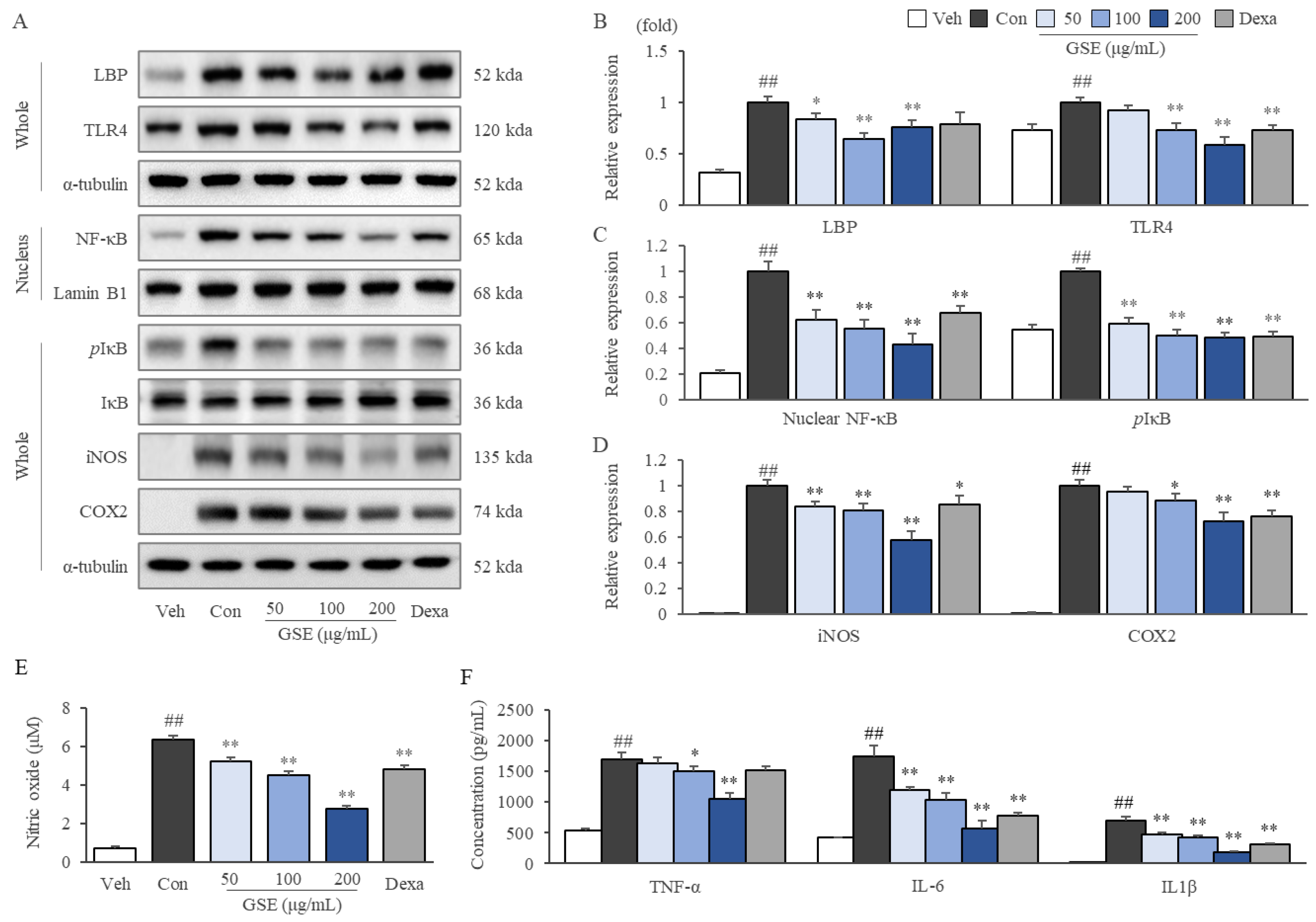

2.6. GSE Modulated the TLR4/NF-κB Pathway in LPS-Stimulated RAW264.7 Cells

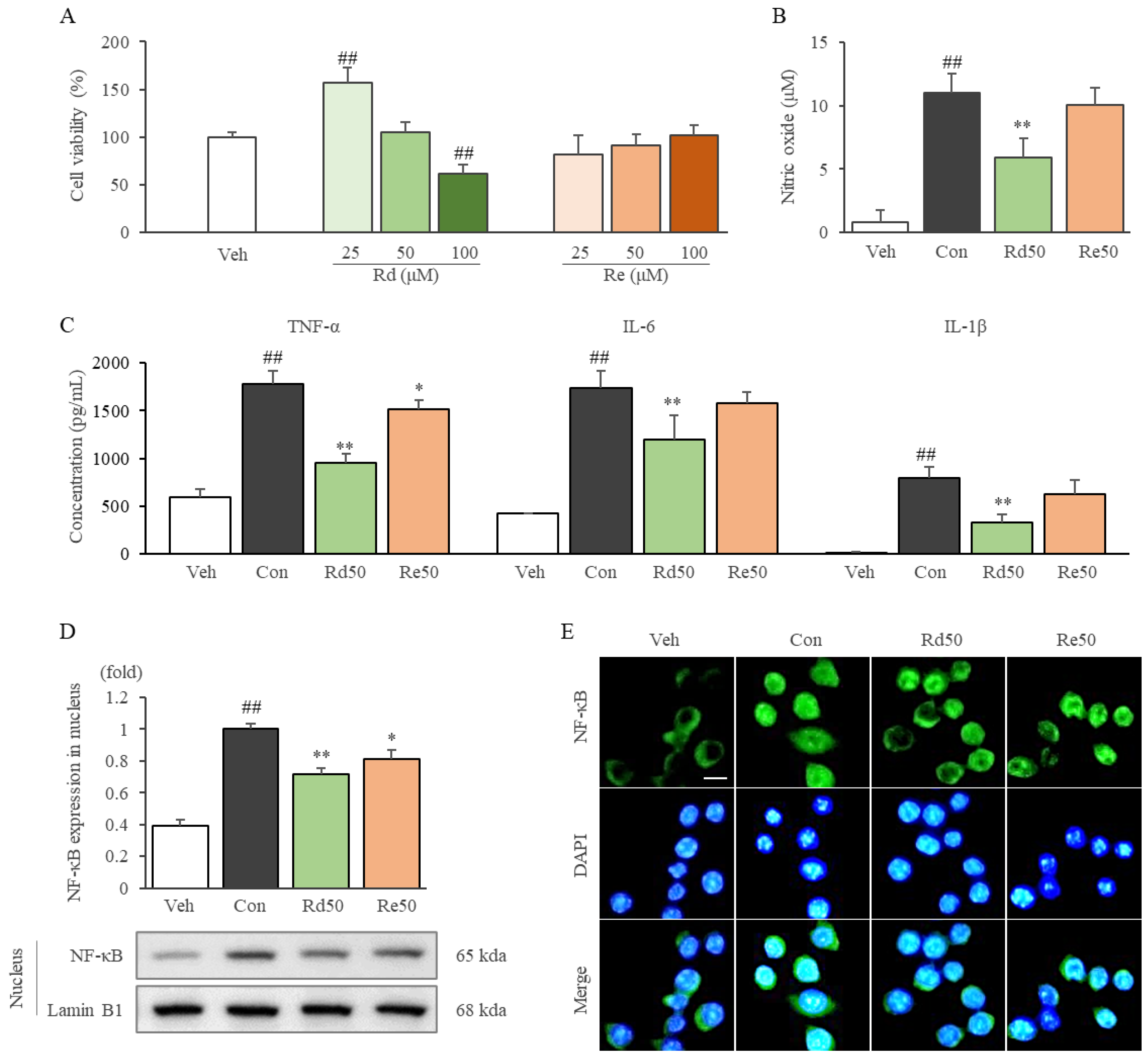

2.7. Ginsenoside Rd Inhibited Inflammatory Cytokines and Mediators by Suppressing the Nuclear Translocation of NF-κB in LPS-Stimulated RAW264.7 Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Preparation of Ginseng Sprout Extract

4.3. HPLC Fingerprinting Analysis

4.4. Animal Experiments and Ethics Approval

4.5. Cell Culture and Chemical Treatment

4.6. Cell Viability

4.7. Determination of NO

4.8. Determination of Proinflammatory Cytokines

4.9. Histopathological Analysis

4.10. Western Blot Analysis

4.11. Nuclear Translocation of NF-κB

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M. Definizioni di Sepsis e Septic Shock. JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, K.E.; Johnson, S.C.; Agesa, K.M.; Shackelford, K.A.; Tsoi, D.; Kievlan, D.R.; Colombara, D.V.; Ikuta, K.S.; Kissoon, N.; Finfer, S. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 395, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Jones, G.; David, S.; Olariu, E.; Cadwell, K.K. Frequency and mortality of septic shock in Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coopersmith, C.M.; Wunsch, H.; Fink, M.P.; Linde-Zwirble, W.T.; Olsen, K.M.; Sommers, M.S.; Anand, K.J.; Tchorz, K.M.; Angus, D.C.; Deutschman, C.S. A comparison of critical care research funding and the financial burden of critical illness in the United States. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delano, M.J.; Ward, P.A. The immune system’s role in sepsis progression, resolution, and long-term outcome. Immunol. Rev. 2016, 274, 330–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J. Natural killer cells in sepsis: Detrimental role for final outcome. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 1579–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. the role and mechanisms of macrophage autophagy in sepsis. Inflammation 2019, 42, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Guo, H.; Wang, T. Schizandrin B protects LPS-induced sepsis via TLR4/NF-κB/MyD88 signaling pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 1155. [Google Scholar]

- Mullarkey, M.; Rose, J.R.; Bristol, J.; Kawata, T.; Kimura, A.; Kobayashi, S.; Przetak, M.; Chow, J.; Gusovsky, F.; Christ, W.J. Inhibition of endotoxin response by e5564, a novel Toll-like receptor 4-directed endotoxin antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 304, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sha, T.; Sunamoto, M.; Kitazaki, T.; Sato, J.; Ii, M.; Iizawa, Y. Therapeutic effects of TAK-242, a novel selective Toll-like receptor 4 signal transduction inhibitor, in mouse endotoxin shock model. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 571, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, T.W.; Wheeler, A.P.; Bernard, G.R.; Vincent, J.-L.; Angus, D.C.; Aikawa, N.; Demeyer, I.; Sainati, S.; Amlot, N.; Cao, C. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of TAK-242 for the treatment of severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 38, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidswell, M.; Tillis, W.; LaRosa, S.P.; Lynn, M.; Wittek, A.E.; Kao, R.; Wheeler, J.; Gogate, J.; Opal, S.M.; Group, E.S.S. Phase 2 trial of eritoran tetrasodium (E5564), a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, in patients with severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 38, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, D.S.; Pantuso, T. Panax ginseng. Am. Fam. Physician 2003, 68, 1539–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.-M.; Yao, Q.; Chen, C. Ginseng compounds: An update on their molecular mechanisms and medical applications. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2009, 7, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kang, J.-Y.; Kim, D.-Y.; Lee, J.-S.; Hwang, S.-J.; Kim, G.-H.; Hyun, S.-H.; Son, C.-G. Korean red ginseng ameliorates fatigue via modulation of 5-HT and corticosterone in a sleep-deprived mouse model. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.-D.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, S.H.; Chung, S.H. Ginseng and diabetes: The evidences from in vitro, animal and human studies. J. Ginseng Res. 2012, 36, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, M.-X.; Wei, Q.-Q.; Lu, H.-J. Progress on the Elucidation of the Antinociceptive Effect of Ginseng and Ginsenosides in Chronic Pain. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 821940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, S.; Choe, J.H.; Choi, G.-E.; Kim, J.-E.; Kim, J.-M.; Song, G.Y.; Jo, E.-K. Rg6, a rare ginsenoside, inhibits systemic inflammation through the induction of interleukin-10 and microRNA-146a. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baik, I.-H.; Kim, K.-H.; Lee, K. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Antithrombotic Effects of Ginsenoside Compound K Enriched Extract Derived from Ginseng Sprouts. Molecules 2021, 26, 4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-S.; Jung, S.; Jee, S.; Yoon, J.W.; Byeon, Y.S.; Park, S.; Kim, S.B. Growth and bioactive phytochemicals of Panax ginseng sprouts grown in an aeroponic system using plasma-treated water as the nitrogen source. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Chung, J.H.; Yoon, J.S.; Ha, Y.M.; Bae, S.; Lee, E.K.; Jung, K.J.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, M.K. Ginsenoside Rd inhibits the expressions of iNOS and COX-2 by suppressing NF-κB in LPS-stimulated RAW264. 7 cells and mouse liver. J. Ginseng Res. 2013, 37, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bian, Y.; Dong, Y.; Sun, J.; Sun, M.; Hou, Q.; Lai, Y.; Zhang, B. Protective effect of kaempferol on LPS-induced inflammation and barrier dysfunction in a coculture model of intestinal epithelial cells and intestinal microvascular endothelial cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 68, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Lu, K.; Ye, T.; Zhang, Z. MicroRNA-223 attenuates LPS-induced inflammation in an acute lung injury model via the NLRP3 inflammasome and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway via RHOB. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 43, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deitch, E.A. Rodent models of intra-abdominal infection. Shock 2005, 24, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgescu, A.M.; Banescu, C.; Azamfirei, R.; Hutanu, A.; Moldovan, V.; Badea, I.; Voidazan, S.; Dobreanu, M.; Chirtes, I.R.; Azamfirei, L. Evaluation of TNF-α genetic polymorphisms as predictors for sepsis susceptibility and progression. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remick, D.G.; Bolgos, G.R.; Siddiqui, J.; Shin, J.; Nemzek, J.A. Six at six: Interleukin-6 measured 6 h after the initiation of sepsis predicts mortality over 3 days. Shock 2002, 17, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, A.A.A.-M.; Suliman, G.A. The predictive prognostic values of serum TNF-α in comparison to SOFA score monitoring in critically ill patients. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 258029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, J.; Park, D.W.; Moon, S.; Cho, H.-J.; Park, J.H.; Seok, H.; Choi, W.S. Diagnostic and prognostic value of interleukin-6, pentraxin 3, and procalcitonin levels among sepsis and septic shock patients: A prospective controlled study according to the Sepsis-3 definitions. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panacek, E.A.; Marshall, J.C.; Albertson, T.E.; Johnson, D.H.; Johnson, S.; MacArthur, R.D.; Miller, M.; Barchuk, W.T.; Fischkoff, S.; Kaul, M. Efficacy and safety of the monoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody F (ab’)2 fragment afelimomab in patients with severe sepsis and elevated interleukin-6 levels. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, D.; Li, J. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19: A single center experience. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavaillon, J.-M.; Adib-Conquy, M. Monocytes/macrophages and sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 33, S506–S509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.S. Sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock: Changes in incidence, pathogens and outcomes. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2012, 10, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Sakr, Y.; Sprung, C.L.; Ranieri, V.M.; Reinhart, K.; Gerlach, H.; Moreno, R.; Carlet, J.; Le Gall, J.-R.; Payen, D. Sepsis in European intensive care units: Results of the SOAP study. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haj, L.; Bestle, M.H. Nitric oxide and sepsis. Ugeskr. Laeg. 2017, 179, V01170086. [Google Scholar]

- Lambden, S. Bench to bedside review: Therapeutic modulation of nitric oxide in sepsis—An update. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2019, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, J.; Grover, R.; McLuckie, A.; Holzapfel, L.; Andersson, J.; Lodato, R.; Watson, D.; Grossman, S.; Donaldson, J.; Takala, J. Administration of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-methyl-L-arginine hydrochloride (546C88) by intravenous infusion for up to 72 hours can promote the resolution of shock in patients with severe sepsis: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study (study no. 144-002). Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- López, A.; Lorente, J.A.; Steingrub, J.; Bakker, J.; McLuckie, A.; Willatts, S.; Brockway, M.; Anzueto, A.; Holzapfel, L.; Breen, D. Multiple-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor 546C88: Effect on survival in patients with septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belok, S.H.; Bosch, N.A.; Klings, E.S.; Walkey, A.J. Evaluation of leukopenia during sepsis as a marker of sepsis-defining organ dysfunction. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnello, L.; Giglio, R.V.; Bivona, G.; Scazzone, C.; Gambino, C.M.; Iacona, A.; Ciaccio, A.M.; Lo Sasso, B.; Ciaccio, M. The value of a complete blood count (CBC) for sepsis diagnosis and prognosis. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzmich, N.N.; Sivak, K.V.; Chubarev, V.N.; Porozov, Y.B.; Savateeva-Lyubimova, T.N.; Peri, F. TLR4 signaling pathway modulators as potential therapeutics in inflammation and sepsis. Vaccines 2017, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ciesielska, A.; Matyjek, M.; Kwiatkowska, K. TLR4 and CD14 trafficking and its influence on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 1233–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhu, Y.; Ouyang, M.Z.; Zhang, M.; Tang, K.; Niu, C.C.; Li, L. Knockout of Toll-like receptor 4 improves survival and cardiac function in a murine model of severe sepsis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 5368–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jang, I.B.; Yu, J.; Suh, S.J.; Jang, I.B.; Kwon, K.B. Growth and ginsenoside content in different parts of ginseng sprouts depending on harvest time. Korean J. Med. Crop Sci. 2018, 26, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, B.J.; Kim, S.I.; Jee, M.G.; Lee, H.C.; Kwon, A.R.; Kim, H.H.; Won, J.Y.; Lee, K.S. Changes in growth, active ingredients, and rheological properties of greenhouse-cultivated ginseng sprout during its growth period. Korean J. Med. Crop Sci. 2019, 27, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ren, K.; Jin, C.; Ma, P.; Ren, Q.; Jia, Z.; Zhu, D. Ginsenoside Rd alleviates mouse acute renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by modulating macrophage phenotype. J. Ginseng Res. 2016, 40, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Yan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Rausch, W.-D. Ginsenoside Rd and ginsenoside Re offer neuroprotection in a novel model of Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2016, 5, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Du, P.; Jiang, D. Berberine functions as a negative regulator in lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis by suppressing NF-κB and IL-6 mediated STAT3 activation. Pathog. Dis. 2020, 78, ftaa047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wan, H.; Yi, L.; Chen, W.; Luo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X. Berberine administrated with different routes attenuates inhaled LPS-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome through TLR4/NF-κB and JAK2/STAT3 inhibition. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 908, 174349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Gu, P.; Shen, H. Protective effects of berberine hydrochloride on DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 68, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hematology Index (109 Cell/L) | Normal | Control | GSE25 | GSE50 | GSE100 | Dexa5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell | 9.98 ± 1.47 | 4.88 ± 0.29 ## | 4.30 ± 0.94 | 5.58 ± 2.19 | 6.82 ± 1.45 * | 5.98 ± 0.77 * |

| Lymphocyte | 7.84 ± 0.92 | 2.70 ± 0.39 ## | 2.55 ± 0.64 | 3.53 ± 0.64 | 5.02 ± 1.92 * | 1.95 ± 1.64 * |

| Monocyte | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 0.70 ± 0.07 ## | 0.60 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.16 | 0.54 ± 0.11 * | 0.83 ± 0.11 |

| Granulocyte | 1.60 ± 0.56 | 1.48 ± 0.36 | 1.15 ± 0.23 | 1.45 ± 0.48 | 1.26 ± 0.30 | 3.20 ± 0.39 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, S.-J.; Wang, J.-H.; Lee, J.-S.; Kang, J.-Y.; Baek, D.-C.; Kim, G.-H.; Ahn, Y.-C.; Son, C.-G. Ginseng Sprouts Attenuate Mortality and Systemic Inflammation by Modulating TLR4/NF-κB Signaling in an LPS-Induced Mouse Model of Sepsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021583

Hwang S-J, Wang J-H, Lee J-S, Kang J-Y, Baek D-C, Kim G-H, Ahn Y-C, Son C-G. Ginseng Sprouts Attenuate Mortality and Systemic Inflammation by Modulating TLR4/NF-κB Signaling in an LPS-Induced Mouse Model of Sepsis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(2):1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021583

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Seung-Ju, Jing-Hua Wang, Jin-Seok Lee, Ji-Yun Kang, Dong-Cheol Baek, Geon-Ho Kim, Yo-Chan Ahn, and Chang-Gue Son. 2023. "Ginseng Sprouts Attenuate Mortality and Systemic Inflammation by Modulating TLR4/NF-κB Signaling in an LPS-Induced Mouse Model of Sepsis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 2: 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021583