Tumor-Associated Macrophage Subsets: Shaping Polarization and Targeting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. M2-like Macrophages

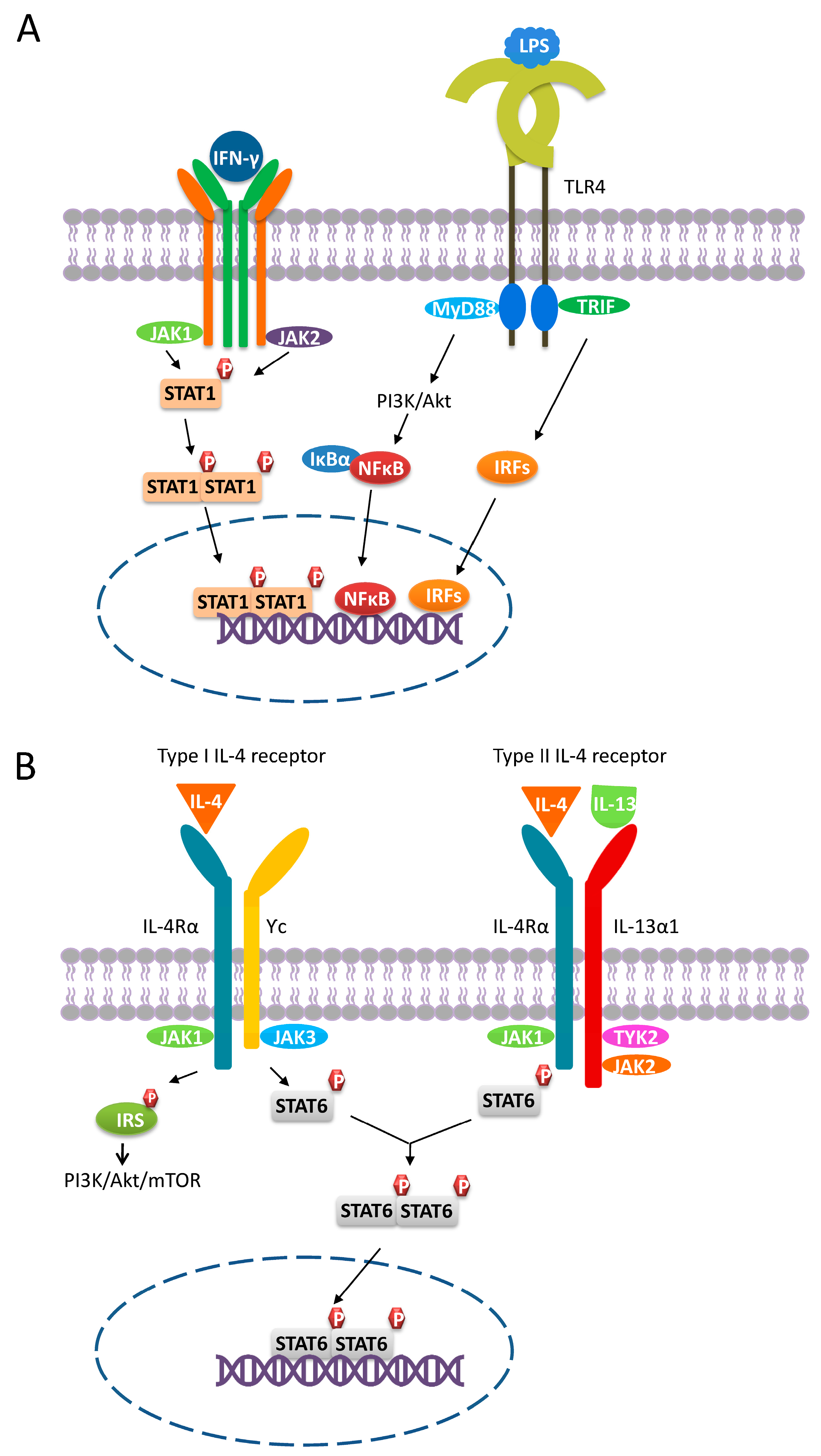

2.1. M2a Macrophages

Pro-Tumoral Effects of M2a Macrophages

2.2. M2b Macrophages

Pro-Tumoral Effects of M2b Macrophages

2.3. M2c Macrophages

Pro-Tumoral Effects of M2c Macrophages

2.4. M2d Macrophages

Pro-Tumoral Effects of M2d Macrophages

3. TAMs as a Target for Cancer Therapy

3.1. Blocking Monocyte/Macrophage Recruitment to Tumors

3.2. Restoring Macrophage Intrinsic Functions

3.2.1. Enhancement of Phagocytosis by Blocking the CD47/SIRPα Axis

| Strategy | Examples | Benefits | Side Effects | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of monocyte/ macrophage recruitment | M-CSF/CSF1R blockade | Small molecules: PLX3397, PLX7486, JNJ-40346527, ARRY-382, BLZ945, CS2164 | Eliminate circulating monocytes/TAMs and restore T cell infiltration | Systemic symptoms including Anemia; neutropenia; hepatotoxicity; hypertension | [11,13,15] |

| Monoclonal antibodies: RG7155, IMC-CS4, R05509554, RG7155, FPA008, AMG820, LY3022855, PD-0360324 | |||||

| CCL2/CCR2 blockade | CCL2 inhibitor (Carlumab) CCR2 inhibitor (PF-04136309) | Eliminate circulating monocytes/TAMs | No effect on resident TAMs; relapse; pulmonary toxicity | [23] | |

| Depletion of monocytes/ macrophages | Inorganic compounds: Bisphosphonates and its derivatives | Useful in killing monocytes, macrophages, and tumor cells in bone metastases | Short plasma half-life, rapid kidney clearance | [11,15,105] | |

| Chemical agents: Trabectedin, lurbinectedin | Cytotoxic to tumor cells, monocytes, TAMs, and MDSCs | Anaphylaxis, neutropenic sepsis, rhabdomyolysis, hepatotoxicity, cardiomyopathy, capillary leak syndrome, and tissue necrosis | [11,13,15,106] | ||

| M2 targeting peptides: NW, M2pep, UNO, Melittin, RP182, LyP-1 | Highly specific; drug delivery and imaging; less immunogenic; cheap and easy to synthesize; high penetration rate | Unstable bio-stability | [11,89,90,91,92,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131] | ||

| Restoring macrophage intrinsic functions | Enhance phagocytosis | CD47 targeting peptides: Anti-CD47 antibodies: Hu5F9-G4, CC-90002, SRF231, IBI188, ZL1201, TTI-621, ALX148 | Enhance macrophage functions (phagocytosis, antigen presentation, ADCC); induce tumor cell apoptosis; repolarize TAMs towards M1 | Anemia; nausea; headache; isolated neutropenia | [11,13,15] |

| pep-20, pep20-D12, TAX2 | [100,101,102] | ||||

| Anti-SIRPα antibodies: Velcro-CD47, KWAR23, ADU-1805 | [98] | ||||

| Enhance antigen presentation | Anti-CD40 antibodies: CP-870,893, ChiLob7/4, RO7009789 | Prime T cell activation; promote anti-tumoral factors secretion; alter M2 cytokine profile | Cytokine release syndrome; liver toxicity | [11,13,15,105,132,133] | |

3.2.2. Enhancement of Antigen Presentation via Enhancing CD40/CD40L Interaction

3.2.3. CAR-Macrophages

3.3. Reprogramming of TAMs

3.4. Depletion of Monocytes/TAMs

3.4.1. Biophosphonate

3.4.2. Trabectedin

3.4.3. Targeting Peptides

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADCC | Antigen-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| ADCP | Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis |

| ALD-DNA | Activated lymphocyte derived DNA |

| APC | Antigen presenting cell |

| Arg1 | Arginase 1 |

| BMDM | Bone marrow-derived macrophages |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EPR | Enhanced permeability and retention |

| FAM | 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein |

| FcγR | Fcγ receptor |

| GAS | Growth arrest specific |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| IC | Immunocomplex |

| IDO | Indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL-10R | IL-10 receptor |

| IL-6R | IL-6 receptor |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IRS | Insulin receptor substrate |

| ITAM | Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| LIF | leukemia inhibitory factor |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony stimulating factor |

| MerTK | Mer tyrosine kinase |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| mUNO | Minimal functional motif derived from UNO peptide |

| PE | Phycoerythrin |

| PHB1 | Prohibitin 1 |

| PITPNM3 | Phosphatidylinositol transfer membrane-associated protein |

| PRR | Pattern recognition receptor |

| RBC | Red blood cell |

| SIRPα | Signal regulatory protein-α |

| SPHK1 | Sphingosine kinase 1 |

| STAT6 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophage |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TRAILR | TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptors |

| TSP-1 | Thrombospondin-1 |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Vitale, I.; Manic, G.; Coussens, L.M.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Macrophages and Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, A.; Hsiao, Y.J.; Chen, H.Y.; Chen, H.W.; Ho, C.C.; Chen, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Hong, T.H.; Yu, S.L.; Chen, J.J.; et al. Opposite Effects of M1 and M2 Macrophage Subtypes on Lung Cancer Progression. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Jiang, L.; Hao, S.; Liu, Z.; Ding, S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Li, S. Activation of the IL-4/STAT6 Signaling Pathway Promotes Lung Cancer Progression by Increasing M2 Myeloid Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, C.H.; Chen, F.M.; Lin, Y.C.; Tsai, M.L.; Wang, S.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.T.; Hou, M.F. Altered monocyte differentiation and macrophage polarization patterns in patients with breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ji, X.; Kang, N.; Zhou, J.; Liang, X.; Li, J.; Han, T.; Zhao, C.; Yang, T. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibition overcomes immunosuppressive M2b macrophage-induced bevacizumab resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chen, Y.S.; Yao, Y.D.; Chen, J.Q.; Chen, J.N.; Huang, S.Y.; Zeng, Y.J.; Yao, H.R.; Zeng, S.H.; Fu, Y.S.; et al. CCL18 from tumor-associated macrophages promotes angiogenesis in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 34758–34773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, A.C.; Pathanjeli, P.; Wu, Z.; Bao, L.; Goo, L.E.; Yates, J.A.; Oliver, C.R.; Soellner, M.B.; Merajver, S.D. IL-4/IL-13 Stimulated Macrophages Enhance Breast Cancer Invasion Via Rho-GTPase Regulation of Synergistic VEGF/CCL-18 Signaling. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, A.; Tsuchimoto, Y.; Ohama, H.; Fukunishi, S.; Tsuda, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Higuchi, K.; Suzuki, F. Host antitumor resistance improved by the macrophage polarization in a chimera model of patients with HCC. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1299301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.L.; Duan, W.; Su, C.Y.; Mao, F.Y.; Lv, Y.P.; Teng, Y.S.; Yu, P.W.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhao, Y.L. Interleukin 6 induces M2 macrophage differentiation by STAT3 activation that correlates with gastric cancer progression. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Koh, J.; Ko, J.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, H.; Chung, D.H. Ubiquitin E3 Ligase Pellino-1 Inhibits IL-10-mediated M2c Polarization of Macrophages, Thereby Suppressing Tumor Growth. Immune Netw. 2019, 19, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourani, T.; Holden, J.A.; Li, W.; Lenzo, J.C.; Hadjigol, S.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M. Tumor Associated Macrophages: Origin, Recruitment, Phenotypic Diversity, and Targeting. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 788365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugel, S.; De Sanctis, F.; Mandruzzato, S.; Bronte, V. Tumor-induced myeloid deviation: When myeloid-derived suppressor cells meet tumor-associated macrophages. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 3365–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anfray, C.; Ummarino, A.; Andón, F.T.; Allavena, P. Current Strategies to Target Tumor-Associated-Macrophages to Improve Anti-Tumor Immune Responses. Cells 2019, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.E.; Pollard, J.W. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassetta, L.; Pollard, J.W. Targeting macrophages: Therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, A.J.; Elsawa, S.F. Macrophage Polarization States in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlsson, S.M.; Linge, C.P.; Gullstrand, B.; Lood, C.; Johansson, Å.; Ohlsson, S.; Lundqvist, A.; Bengtsson, A.A.; Carlsson, F.; Hellmark, T. Serum from patients with systemic vasculitis induces alternatively activated macrophage M2c polarization. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 152, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sudan, K.; Schmoeckel, E.; Kost, B.P.; Kuhn, C.; Vattai, A.; Vilsmaier, T.; Mahner, S.; Jeschke, U.; Heidegger, H.H. CCL22-Polarized TAMs to M2a Macrophages in Cervical Cancer In Vitro Model. Cells 2022, 11, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, I.; Asai, A.; Suzuki, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Suzuki, F. M2b macrophage polarization accompanied with reduction of long noncoding RNA GAS5. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 493, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizzo, G.; Hilliard, B.A.; Monestier, M.; Cohen, P.L. Efficient clearance of early apoptotic cells by human macrophages requires M2c polarization and MerTK induction. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 3508–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.P.; Zhang, X.; Frauwirth, K.A.; Mosser, D.M. Biochemical and functional characterization of three activated macrophage populations. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 80, 1298–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahmar, Q.; Keirsse, J.; Laoui, D.; Movahedi, K.; Van Overmeire, E.; Van Ginderachter, J.A. Tissue-resident versus monocyte-derived macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1865, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNardo, D.G.; Ruffell, B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ailuno, G.; Baldassari, S.; Zuccari, G.; Schlich, M.; Caviglioli, G. Peptide-based nanosystems for vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 targeting: A real opportunity for therapeutic and diagnostic agents in inflammation associated disorders. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 101461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettschureck, N.; Strilic, B.; Offermanns, S. Passing the Vascular Barrier: Endothelial Signaling Processes Controlling Extravasation. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1467–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riabov, V.; Gudima, A.; Wang, N.; Mickley, A.; Orekhov, A.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Role of tumor associated macrophages in tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.S.; Lee, J.; Ferrara, N. Targeting the tumour vasculature: Insights from physiological angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, R.; Kassner, P.D.; Carr, M.W.; Finger, E.B.; Hemler, M.E.; Springer, T.A. The integrin VLA-4 supports tethering and rolling in flow on VCAM-1. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 128, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.D.; Kincaid, K.; Alt, J.M.; Heilman, M.J.; Hill, A.M. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 6166–6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skytthe, M.K.; Graversen, J.H.; Moestrup, S.K. Targeting of CD163(+) Macrophages in Inflammatory and Malignant Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: Time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orecchioni, M.; Ghosheh, Y.; Pramod, A.B.; Ley, K. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS-) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneemann, M.; Schoeden, G. Macrophage biology and immunology: Man is not a mouse. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007, 81, 579; discussion 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosser, D.M.; Edwards, J.P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.K.; Mantovani, A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: Cancer as a paradigm. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, M.; Keshav, S.; Harris, N.; Gordon, S. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: A marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J. Exp. Med. 1992, 176, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyken, S.J.; Locksley, R.M. Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated alternatively activated macrophages: Roles in homeostasis and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 31, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Villarino, G.; Troegeler, A.; Balboa, L.; Lastrucci, C.; Duval, C.; Mercier, I.; Bénard, A.; Capilla, F.; Al Saati, T.; Poincloux, R.; et al. The C-Type Lectin Receptor DC-SIGN Has an Anti-Inflammatory Role in Human M(IL-4) Macrophages in Response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa Santos, M.A.R.; Dos Reis, J.S.; do Nascimento Santos, C.A.; da Costa, K.M.; Barcelos, P.M.; de Oliveira Francisco, K.Q.; Barbosa, P.; da Silva, E.D.S.; Freire-de-Lima, C.G.; Morrot, A.; et al. Expression of O-glycosylated oncofetal fibronectin in alternatively activated human macrophages. Immunol. Res. 2023, 71, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S.; Locati, M.; Mantovani, A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: New molecules and patterns of gene expression. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 7303–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratchev, A.; Guillot, P.; Hakiy, N.; Politz, O.; Orfanos, C.E.; Schledzewski, K.; Goerdt, S. Alternatively activated macrophages differentially express fibronectin and its splice variants and the extracellular matrix protein betaIG-H3. Scand. J. Immunol. 2001, 53, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.H.; Du, W.D.; Li, Y.F.; Al-Aroomi, M.A.; Yan, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Liu, F.Y.; Sun, C.F. The Overexpression of Fibronectin 1 Promotes Cancer Progression and Associated with M2 Macrophages Polarization in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 5027–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xing, Z.; Lou, C.; Fang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; He, H.; Bai, H. Fibronectin 1 derived from tumor-associated macrophages and fibroblasts promotes metastasis through the JUN pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 113, 109420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, S.; Tocci, A.; Di Modugno, F.; Nisticò, P. Fibronectin as a multiregulatory molecule crucial in tumor matrisome: From structural and functional features to clinical practice in oncology. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Otal, C.; Lasarte-Cia, A.; Serrano, D.; Casares, N.; Conde, E.; Navarro, F.; Sánchez-Moreno, I.; Gorraiz, M.; Sarrión, P.; Calvo, A.; et al. Targeting the extra domain A of fibronectin for cancer therapy with CAR-T cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junttila, I.S. Tuning the Cytokine Responses: An Update on Interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 Receptor Complexes. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirey, K.A.; Cole, L.E.; Keegan, A.D.; Vogel, S.N. Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain induces macrophage alternative activation as a survival mechanism. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 4159–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, N.M.; Qi, X.; Junttila, I.S.; Shirey, K.A.; Vogel, S.N.; Paul, W.E.; Keegan, A.D. Type I IL-4Rs selectively activate IRS-2 to induce target gene expression in macrophages. Sci. Signal. 2008, 1, ra17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiratori, H.; Feinweber, C.; Luckhardt, S.; Linke, B.; Resch, E.; Geisslinger, G.; Weigert, A.; Parnham, M.J. THP-1 and human peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived macrophages differ in their capacity to polarize in vitro. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 88, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, S.; De Majo, F.; Kim, J.; Trenti, A.; Trevisi, L.; Fadini, G.P.; Bolego, C.; Zandstra, P.W.; Cignarella, A.; Vitiello, L. Convenience versus Biological Significance: Are PMA-Differentiated THP-1 Cells a Reliable Substitute for Blood-Derived Macrophages When Studying in Vitro Polarization? Front. Pharm. 2018, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, E.W.; Graham, A.E.; Re, N.A.; Carr, I.M.; Robinson, J.I.; Mackie, S.L.; Morgan, A.W. Standardized protocols for differentiation of THP-1 cells to macrophages with distinct M(IFNγ+LPS), M(IL-4) and M(IL-10) phenotypes. J. Immunol. Methods 2020, 478, 112721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rückerl, D.; Jenkins, S.J.; Laqtom, N.N.; Gallagher, I.J.; Sutherland, T.E.; Duncan, S.; Buck, A.H.; Allen, J.E. Induction of IL-4Rα-dependent microRNAs identifies PI3K/Akt signaling as essential for IL-4-driven murine macrophage proliferation in vivo. Blood 2012, 120, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.F.; Mosser, D.M. A novel phenotype for an activated macrophage: The type 2 activated macrophage. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002, 72, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Zhang, S.X.; Wu, H.J.; Rong, X.L.; Guo, J. M2b macrophage polarization and its roles in diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 106, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Bailey, W.M.; Braun, K.J.; Gensel, J.C. Age decreases macrophage IL-10 expression: Implications for functional recovery and tissue repair in spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 2015, 273, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, A.; Nakamura, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Herndon, D.N.; Suzuki, F. CCL1 released from M2b macrophages is essentially required for the maintenance of their properties. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012, 92, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sironi, M.; Martinez, F.O.; D’Ambrosio, D.; Gattorno, M.; Polentarutti, N.; Locati, M.; Gregorio, A.; Iellem, A.; Cassatella, M.A.; Van Damme, J.; et al. Differential regulation of chemokine production by Fcgamma receptor engagement in human monocytes: Association of CCL1 with a distinct form of M2 monocyte activation (M2b, Type 2). J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 80, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wen, Z.; Xu, W.; Xiong, S. Granulin exacerbates lupus nephritis via enhancing macrophage M2b polarization. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravetch, J.V.; Kinet, J.P. Fc Receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1991, 9, 457–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Fc-receptors as regulators of immunity. Adv. Immunol. 2007, 96, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duluc, D.; Delneste, Y.; Tan, F.; Moles, M.-P.; Grimaud, L.; Lenoir, J.; Preisser, L.; Anegon, I.; Catala, L.; Ifrah, N.; et al. Tumor-associated leukemia inhibitory factor and IL-6 skew monocyte differentiation into tumor-associated macrophage-like cells. Blood 2007, 110, 4319–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, I.; Bhopale, K.K.; Nishiguchi, T.; Lee, J.O.; Herndon, D.N.; Suzuki, S.; Sowers, L.C.; Suzuki, F.; Kobayashi, M. The Polarization of M2b Monocytes in Cultures of Burn Patient Peripheral CD14+ Cells Treated with a Selected Human CCL1 Antisense Oligodeoxynucleotide. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2016, 26, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Wang, N.; Qi, J.; Gu, Z.; Shen, H. Long non-coding RNA-GAS5 acts as a tumor suppressor in bladder transitional cell carcinoma via regulation of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 1 expression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sarrou, E.; Podgrabinska, S.; Cassella, M.; Mungamuri, S.K.; Feirt, N.; Gordon, R.; Nagi, C.S.; Wang, Y.; Entenberg, D.; et al. Tumor cell entry into the lymph node is controlled by CCL1 chemokine expressed by lymph node lymphatic sinuses. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 1509–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.X.; Wei, Y.; Zeng, Q.H.; Chan, K.W.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, X.Y.; Chen, M.M.; Ouyang, F.Z.; Chen, D.P.; Zheng, L.; et al. Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 3-positive B cells link interleukin-17 inflammation to protumorigenic macrophage polarization in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2015, 62, 1779–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duluc, D.; Corvaisier, M.; Blanchard, S.; Catala, L.; Descamps, P.; Gamelin, E.; Ponsoda, S.; Delneste, Y.; Hebbar, M.; Jeannin, P. Interferon-γ reverses the immunosuppressive and protumoral properties and prevents the generation of human tumor-associated macrophages. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, Q.; Cao, D.; Ai, J. Crosstalk between Tumor-Associated Macrophages and MicroRNAs: A Key Role in Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Dong, F.; Lu, J.; Wei, L.; Tian, L.; Ge, H.; Zou, Y.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. Polarized M2c macrophages have a promoting effect on the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of human renal tubular epithelial cells. Immunobiology 2018, 223, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Sica, A.; Sozzani, S.; Allavena, P.; Vecchi, A.; Locati, M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Giraud, F.; Hafner, M.; Ries, C.H. In vitro generation of monocyte-derived macrophages under serum-free conditions improves their tumor promoting functions. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Sica, A.; Mantovani, A.; Locati, M. Macrophage activation and polarization. FBL 2008, 13, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouval, D.S.; Ouahed, J.; Biswas, A.; Goettel, J.A.; Horwitz, B.H.; Klein, C.; Muise, A.M.; Snapper, S.B. Chapter Five-Interleukin 10 Receptor Signaling: Master Regulator of Intestinal Mucosal Homeostasis in Mice and Humans. In Advances in Immunology; Alt, F.W., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 122, pp. 177–210. [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister, A.R.; Marriott, I. The Interleukin-10 Family of Cytokines and Their Role in the CNS. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park-Min, K.H.; Antoniv, T.T.; Ivashkiv, L.B. Regulation of macrophage phenotype by long-term exposure to IL-10. Immunobiology 2005, 210, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koscsó, B.; Csóka, B.; Kókai, E.; Németh, Z.H.; Pacher, P.; Virág, L.; Leibovich, S.J.; Haskó, G. Adenosine augments IL-10-induced STAT3 signaling in M2c macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 94, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Sozzani, S.; Locati, M.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A. Macrophage polarization: Tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002, 23, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Jia, T.; Gong, W.; Ning, B.; Wooley, P.H.; Yang, S.Y. Macrophage Polarization in IL-10 Treatment of Particle-Induced Inflammation and Osteolysis. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patik, I.; Redhu, N.S.; Eran, A.; Bao, B.; Nandy, A.; Tang, Y.; El Sayed, S.; Shen, Z.; Glickman, J.; Fox, J.G.; et al. IL-10 inhibits STAT1-dependent macrophage accumulation during microbiota-induced colitis. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.N.; Etzerodt, A.; Graversen, J.H.; Holthof, L.C.; Moestrup, S.K.; Hokland, M.; Møller, H.J. STAT3 inhibition specifically in human monocytes and macrophages by CD163-targeted corosolic acid-containing liposomes. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2019, 68, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurier, E.B.; Dalton, D.; Dampier, W.; Raman, P.; Nassiri, S.; Ferraro, N.M.; Rajagopalan, R.; Sarmady, M.; Spiller, K.L. Transcriptome analysis of IL-10-stimulated (M2c) macrophages by next-generation sequencing. Immunobiology 2017, 222, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szondy, Z.; Sarang, Z.; Kiss, B.; Garabuczi, É.; Köröskényi, K. Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms Triggered by Apoptotic Cells during Their Clearance. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, N.; Verbruggen, S.; Gijbels, M.J.; Post, M.J.; De Winther, M.P.; Donners, M.M. Anti-inflammatory M2, but not pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages promote angiogenesis in vivo. Angiogenesis 2014, 17, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, K.L.; Anfang, R.R.; Spiller, K.J.; Ng, J.; Nakazawa, K.R.; Daulton, J.W.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. The role of macrophage phenotype in vascularization of tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 4477–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Lin, H.; Wu, G.; Zhu, M.; Li, M. IL-6/STAT3 Is a Promising Therapeutic Target for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 760971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, Y.S.; Tseng, H.Y.; Chen, Y.A.; Shen, P.C.; Al Haq, A.T.; Chen, L.M.; Tung, Y.C.; Hsu, H.L. MCT-1/miR-34a/IL-6/IL-6R signaling axis promotes EMT progression, cancer stemness and M2 macrophage polarization in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ma, K.; Hu, C.; Zhu, H.; Liang, S.; Liu, M.; Xu, N. IL-6 influences the polarization of macrophages and the formation and growth of colorectal tumor. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 17443–17454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, J.; Chalaris, A.; Schmidt-Arras, D.; Rose-John, S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1813, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, U.; Kim, B.; Kim, S.; Han, Y.; Song, Y.S. Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage enhances metastatic potential of ovarian cancer cells through NF-κB activation. Mol. Carcinog. 2018, 57, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, I.H.; Jeong, C.; Yang, J.; Park, S.H.; Hwang, D.S.; Bae, H. Therapeutic Effect of Melittin-dKLA Targeting Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepland, A.; Asciutto, E.K.; Malfanti, A.; Simón-Gracia, L.; Sidorenko, V.; Vicent, M.J.; Teesalu, T.; Scodeller, P. Targeting Pro-Tumoral Macrophages in Early Primary and Metastatic Breast Tumors with the CD206-Binding mUNO Peptide. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 2518–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scodeller, P.; Simón-Gracia, L.; Kopanchuk, S.; Tobi, A.; Kilk, K.; Säälik, P.; Kurm, K.; Squadrito, M.L.; Kotamraju, V.R.; Rinken, A.; et al. Precision Targeting of Tumor Macrophages with a CD206 Binding Peptide. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, P.; Lepland, A.; Scodeller, P.; Fontana, F.; Torrieri, G.; Tiboni, M.; Shahbazi, M.A.; Casettari, L.; Kostiainen, M.A.; Hirvonen, J.; et al. Peptide-guided resiquimod-loaded lignin nanoparticles convert tumor-associated macrophages from M2 to M1 phenotype for enhanced chemotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2021, 133, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, A.; Liu, F.; Chen, K.; Tang, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, K.; Yu, C.; Bian, G.; Guo, H.; Zheng, J.; et al. Programmed death 1 deficiency induces the polarization of macrophages/microglia to the M1 phenotype after spinal cord injury in mice. Neurother. J. Am. Soc. Exp. Neuro Ther. 2014, 11, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowski, R.; Sharma, N.; Reebel, L.; Rodal, M.B.; Peck, A.; West, B.L.; Marimuthu, A.; Severson, P.; Karlin, D.A.; Dowlati, A.; et al. Phase Ib study of the combination of pexidartinib (PLX3397), a CSF-1R inhibitor, and paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2019, 11, 1758835919854238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, D.; Zins, K.; Sioud, M.; Lucas, T.; Schäfer, R.; Stanley, E.R.; Aharinejad, S. Stromal cell-derived CSF-1 blockade prolongs xenograft survival of CSF-1-negative neuroblastoma. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharinejad, S.; Paulus, P.; Sioud, M.; Hofmann, M.; Zins, K.; Schäfer, R.; Stanley, E.R.; Abraham, D. Colony-stimulating factor-1 blockade by antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNAs suppresses growth of human mammary tumor xenografts in mice. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5378–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zins, K.; Sioud, M.; Aharinejad, S.; Lucas, T.; Abraham, D. Modulating the tumor microenvironment with RNA interference as a cancer treatment strategy. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton N. J.) 2015, 1218, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Rao, L.; Yao, H.; Wang, Z.; Ning, P.; Chen, X. Engineering Macrophages for Cancer Immunotherapy and Drug Delivery. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2002054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willingham, S.B.; Volkmer, J.-P.; Gentles, A.J.; Sahoo, D.; Dalerba, P.; Mitra, S.S.; Wang, J.; Contreras-Trujillo, H.; Martin, R.; Cohen, J.D.; et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6662–6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, C.; Jiao, L.; Li, W.; Gou, S.; Li, Y.; Du, J.; Chen, G.; et al. CD47/SIRPα blocking peptide identification and synergistic effect with irradiation for cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanne, A.; Sarazin, T.; Charlé, M.; Moali, C.; Fichel, C.; Boulagnon-Rombi, C.; Callewaert, M.; Andry, M.C.; Diesis, E.; Delolme, F.; et al. Targeting Ovarian Carcinoma with TSP-1:CD47 Antagonist TAX2 Activates Anti-Tumor Immunity. Cancers 2021, 13, 5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanne, A.; Sick, E.; Devy, J.; Floquet, N.; Belloy, N.; Theret, L.; Boulagnon-Rombi, C.; Diebold, M.D.; Dauchez, M.; Martiny, L.; et al. Identification of TAX2 peptide as a new unpredicted anti-cancer agent. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 17981–18000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimbert, P.; Bouguermouh, S.; Baba, N.; Nakajima, T.; Allakhverdi, Z.; Braun, D.; Saito, H.; Rubio, M.; Delespesse, G.; Sarfati, M. Thrombospondin/CD47 interaction: A pathway to generate regulatory T cells from human CD4+ CD25- T cells in response to inflammation. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 3534–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazerounian, S.; Yee, K.O.; Lawler, J. Thrombospondins in cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Bai, X.; Shu, Y.; Ahmad, O.; Shen, P. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages as an antitumor strategy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 183, 114354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabectedin Injection, Powder, Lyophilized, for Solutio-DailyMed. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=472bd78e-be17-4b9d-90f4-9482c3aec9ff (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Asciutto, E.K.; Kopanchuk, S.; Lepland, A.; Simón-Gracia, L.; Aleman, C.; Teesalu, T.; Scodeller, P. Phage-Display-Derived Peptide Binds to Human CD206 and Modeling Reveals a New Binding Site on the Receptor. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioud, M.; Skorstad, G.; Mobergslien, A.; Sæbøe-Larssen, S. A novel peptide carrier for efficient targeting of antigens and nucleic acids to dendritic cells. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2013, 27, 3272–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sioud, M.; Pettersen, S.; Ailte, I.; Fløisand, Y. Targeted Killing of Monocytes/Macrophages and Myeloid Leukemia Cells with Pro-Apoptotic Peptides. Cancers 2019, 11, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Olberg, A.; Sioud, M. Structural Requirements for the Binding of a Peptide to Prohibitins on the Cell Surface of Monocytes/Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieslewicz, M.; Tang, J.; Yu, J.L.; Cao, H.; Zavaljevski, M.; Motoyama, K.; Lieber, A.; Raines, E.W.; Pun, S.H. Targeted delivery of proapoptotic peptides to tumor-associated macrophages improves survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 15919–15924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngambenjawong, C.; Gustafson, H.H.; Pineda, J.M.; Kacherovsky, N.A.; Cieslewicz, M.; Pun, S.H. Serum Stability and Affinity Optimization of an M2 Macrophage-Targeting Peptide (M2pep). Theranostics 2016, 6, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngambenjawong, C.; Pineda, J.M.; Pun, S.H. Engineering an Affinity-Enhanced Peptide through Optimization of Cyclization Chemistry. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016, 27, 2854–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Bae, S.S.; Joo, H.; Bae, H. Melittin suppresses tumor progression by regulating tumor-associated macrophages in a Lewis lung carcinoma mouse model. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 54951–54965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Jeong, H.; Bae, Y.; Shin, K.; Kang, S.; Kim, H.; Oh, J.; Bae, H. Targeting of M2-like tumor-associated macrophages with a melittin-based pro-apoptotic peptide. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaynes, J.M.; Sable, R.; Ronzetti, M.; Bautista, W.; Knotts, Z.; Abisoye-Ogunniyan, A.; Li, D.; Calvo, R.; Dashnyam, M.; Singh, A.; et al. Mannose receptor (CD206) activation in tumor-associated macrophages enhances adaptive and innate antitumor immune responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaax6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes., J.M.; Lopez., H.W.; Martin, G.R.; Yate, C.; Garvin., C.E. Peptides Having Anti-inflammatory Properties. U.S. Patent 2016/0101150, 20 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Song, N.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, J. Recent progress in LyP-1-based strategies for targeted imaging and therapy. Drug Deliv. 2019, 26, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakkonen, P.; Porkka, K.; Hoffman, J.A.; Ruoslahti, E. A tumor-homing peptide with a targeting specificity related to lymphatic vessels. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogal, V.; Zhang, L.; Krajewski, S.; Ruoslahti, E. Mitochondrial/cell-surface protein p32/gC1qR as a molecular target in tumor cells and tumor stroma. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 7210–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakkonen, P.; Akerman, M.E.; Biliran, H.; Yang, M.; Ferrer, F.; Karpanen, T.; Hoffman, R.M.; Ruoslahti, E. Antitumor activity of a homing peptide that targets tumor lymphatics and tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9381–9386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, J.; Kotamraju, V.R.; Seo, J.W.; Agemy, L.; Fogal, V.; Mahakian, L.M.; Peters, D.; Roth, L.; Gagnon, M.K.; Ferrara, K.W.; et al. Specific penetration and accumulation of a homing peptide within atherosclerotic plaques of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7154–7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, L.; Agemy, L.; Kotamraju, V.R.; Braun, G.; Teesalu, T.; Sugahara, K.N.; Hamzah, J.; Ruoslahti, E. Transtumoral targeting enabled by a novel neuropilin-binding peptide. Oncogene 2012, 31, 3754–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Deng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z. Tumor-targeted liposomal drug delivery mediated by a diseleno bond-stabilized cyclic peptide. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, Z.G.; Hamzah, J.; Kotamraju, V.R.; Pang, H.B.; Jansen, S.; Ruoslahti, E. Plaque-penetrating peptide inhibits development of hypoxic atherosclerotic plaque. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2016, 238, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournaire, R.; Simon, M.P.; le Noble, F.; Eichmann, A.; England, P.; Pouysségur, J. A short synthetic peptide inhibits signal transduction, migration and angiogenesis mediated by Tie2 receptor. EMBO Rep. 2004, 5, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Qi, Y.; Min, H.; Ni, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, B.; Qin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Qin, Y.; et al. Cooperatively Responsive Peptide Nanotherapeutic that Regulates Angiopoietin Receptor Tie2 Activity in Tumor Microenvironment To Prevent Breast Tumor Relapse after Chemotherapy. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 5091–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadevoo, S.M.P.; Kim, J.E.; Gunassekaran, G.R.; Jung, H.K.; Chi, L.; Kim, D.E.; Lee, S.H.; Im, S.H.; Lee, B. IL4 Receptor-Targeted Proapoptotic Peptide Blocks Tumor Growth and Metastasis by Enhancing Antitumor Immunity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 2803–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Kwak, W.; Yoo, J.; Na, M.H.; So, I.S.; Kwon, T.H.; Park, H.S.; Huh, S.; Oh, G.T.; et al. Phage display selection of peptides that home to atherosclerotic plaques: IL-4 receptor as a candidate target in atherosclerosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008, 12, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Wei, Y.; Kang, J.; She, Z.G.; Kim, D.; Sailor, M.J.; Ruoslahti, E.; Pang, H.B. Tumor-specific macrophage targeting through recognition of retinoid X receptor beta. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2019, 301, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Pang, H.B.; Kang, J.; Park, J.H.; Ruoslahti, E.; Sailor, M.J. Immunogene therapy with fusogenic nanoparticles modulates macrophage response to Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allavena, P.; Anfray, C.; Ummarino, A.; Andón, F.T. Therapeutic Manipulation of Tumor-associated Macrophages: Facts and Hopes from a Clinical and Translational Perspective. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 3291–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, H.D.; Buhtoiarov, I.N.; Schmidt, B.E.; Berke, G.; Paulnock, D.M.; Sondel, P.M.; Rakhmilevich, A.L. In vivo CD40 ligation can induce T-cell-independent antitumor effects that involve macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 79, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloas, C.; Gill, S.; Klichinsky, M. Engineered CAR-Macrophages as Adoptive Immunotherapies for Solid Tumors. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 783305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Farrukh, H.; Chittepu, V.; Xu, H.; Pan, C.X.; Zhu, Z. CAR race to cancer immunotherapy: From CAR T, CAR NK to CAR macrophage therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepisi, G.; Gianni, C.; Palleschi, M.; Bleve, S.; Casadei, C.; Lolli, C.; Ridolfi, L.; Martinelli, G.; De Giorgi, U. The New Frontier of Immunotherapy: Chimeric Antigen Receptor T (CAR-T) Cell and Macrophage (CAR-M) Therapy against Breast Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klichinsky, M.; Ruella, M.; Shestova, O.; Lu, X.M.; Best, A.; Zeeman, M.; Schmierer, M.; Gabrusiewicz, K.; Anderson, N.R.; Petty, N.E.; et al. Human chimeric antigen receptor macrophages for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.C.; Park, J.M.; Zhang, K.; Luo, J.L.; Maeda, S.; Kaufman, R.J.; Eckmann, L.; Guiney, D.G.; Karin, M. The protein kinase PKR is required for macrophage apoptosis after activation of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature 2004, 428, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jing, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, G.; Abdalla, M.; Gao, L.; Han, M.; Shi, C.; Li, A.; Sun, P.; et al. Intracavity generation of glioma stem cell-specific CAR macrophages primes locoregional immunity for postoperative glioblastoma therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabn1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodell, C.B.; Arlauckas, S.P.; Cuccarese, M.F.; Garris, C.S.; Li, R.; Ahmed, M.S.; Kohler, R.H.; Pittet, M.J.; Weissleder, R. TLR7/8-agonist-loaded nanoparticles promote the polarization of tumour-associated macrophages to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, A.; Digifico, E.; Andon, F.T.; Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P. Poly(I:C) stimulation is superior than Imiquimod to induce the antitumoral functional profile of tumor-conditioned macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 2019, 49, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefèvre, L.; Galès, A.; Olagnier, D.; Bernad, J.; Perez, L.; Burcelin, R.; Valentin, A.; Auwerx, J.; Pipy, B.; Coste, A. PPARγ ligands switched high fat diet-induced macrophage M2b polarization toward M2a thereby improving intestinal Candida elimination. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeannin, P.; Duluc, D.; Delneste, Y. IL-6 and leukemia-inhibitory factor are involved in the generation of tumor-associated macrophage: Regulation by IFN-γ. Immunotherapy 2011, 3 (Suppl. S4), 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tap, W.D.; Gelderblom, H.; Palmerini, E.; Desai, J.; Bauer, S.; Blay, J.Y.; Alcindor, T.; Ganjoo, K.; Martín-Broto, J.; Ryan, C.W.; et al. Pexidartinib versus placebo for advanced tenosynovial giant cell tumour (ENLIVEN): A randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNardo, D.G.; Brennan, D.J.; Rexhepaj, E.; Ruffell, B.; Shiao, S.L.; Madden, S.F.; Gallagher, W.M.; Wadhwani, N.; Keil, S.D.; Junaid, S.A.; et al. Leukocyte complexity predicts breast cancer survival and functionally regulates response to chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2011, 1, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelderblom, H.; Wagner, A.J.; Tap, W.D.; Palmerini, E.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Desai, J.; Healey, J.H.; van de Sande, M.A.J.; Bernthal, N.M.; Staals, E.L.; et al. Long-term outcomes of pexidartinib in tenosynovial giant cell tumors. Cancer 2021, 127, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, L.; Pei, Y.; Uzunalli, G.; Hyun, H.; Lyle, L.T.; Yeo, Y. Surface Modification of Polymeric Nanoparticles with M2pep Peptide for Drug Delivery to Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingasamy, P.; Teesalu, T. Homing Peptides for Cancer Therapy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1295, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoschky, B.; Pleli, T.; Schmithals, C.; Zeuzem, S.; Brüne, B.; Vogl, T.J.; Korf, H.W.; Weigert, A.; Piiper, A. Selective targeting of tumor associated macrophages in different tumor models. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.M.; Haratipour, P.; Lingeman, R.G.; Perry, J.J.P.; Gu, L.; Hickey, R.J.; Malkas, L.H. Novel Peptide Therapeutic Approaches for Cancer Treatment. Cells 2021, 10, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioud, M.; Westby, P.; Olsen, J.K.; Mobergslien, A. Generation of new peptide-Fc fusion proteins that mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against different types of cancer cells. Mol. Therapy. Methods Clin. Dev. 2015, 2, 15043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, K.; Sun, B.; Gao, Z.; Wang, L. Macrophages and Metabolic Reprograming in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 795159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, S.; Baldassari, S.; Ailuno, G.; Zuccari, G.; Drava, G.; Petretto, A.; Cossu, V.; Marini, C.; Alfei, S.; Florio, T.; et al. Two Novel PET Radiopharmaceuticals for Endothelial Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) Targeting. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, I.; Martinet, W.; De Meyer, G.R. Therapeutic strategies to deplete macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 74, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthel, S.R.; Gavino, J.D.; Descheny, L.; Dimitroff, C.J. Targeting selectins and selectin ligands in inflammation and cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2007, 11, 1473–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Macrophage Subset | Stimulators | Phenotypic Markers | Secreted Molecules | Produced Enzymes | Other Molecules | Functions in Cancer | Associated Cancer Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (classical activated macrophages) | LPS and IFN-Ƴ | CD80/86high, MHCIIhigh, TLR2, TLR4, CCR7high | IL-12, TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-23, CXCL9, CXCL10 | iNOS | GAS5 | Inhibit cancer growth and progression (in general) | Ovarian cancer (M1 promoted cancer cell invasion ability via NFκB-mediated signaling [88]) |

| M2a (wound-healing macrophages) | IL-4 and/or IL-13 | CD206high, CD209high, Dectin-1high, CD163low–medium, CD86low, CD14low–medium, IL-1R | IL-10, TGF-β, CCL17, CCL18, CCL22, CCL24, IGF, EPGF, IL-4 | Arg1 | GAS5, GAS6 | Tissue repair, metastasis [7], invasion [7,89], promote tumor cell proliferation [3,89] | Lung cancer [2,3], breast cancer [4,7,90,91,92], melanoma [89,91], glioma [91], gastric carcinoma [91], cervical cancer [18] |

| M2b (regulatory macrophages) | IC and TLR agonists (i.e., LPS)/IC and IL-1R agonists (i.e., IL-1β) | CD163low, CD86medium–high, MHCIIhigh, CD14medium | IL-10, SPHK1, CCL1, TNF-α, IL-6, LIGHT, IL-1 | iNOS, SPHK1 | No GAS5 expression | Promote tumor growth [8], metastasis [5] | Hepatocellular carcinoma [8,93], bevacizumab resistant triple-negative breast cancer [5], breast cancer [4] |

| M2c (acquired deactivation macrophages) | IL-10, glucocorticoids, TGF-β | CD163high, CD14medium, CD206low–medium, CD86medium, MerTKmedium–high, CD16, TLR1, TLR8 | IL-10, TGF-β, CCL16, CCL18, CCL13 | Arg1 | GAS6 | Phagocyte apoptotic cells [20] | Lung cancer [2], breast cancer [4], mouse melanoma, and lymphoma [10] |

| M2d (tumor-associated macrophages) | IL-6/TLR ligands and A2 adenosine receptor agonists (i.e., LIF) | CD163high, CD86low, CD14high | IL-10, IL-6, CCL18, M-CSF | iNOS | Angiogenesis and metastasis | Ovarian cancer [61], gastric cancer [9] |

| Category | Strategies | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| M1 to M2a | Promote STAT6 signaling: PD-1 exposure | [93] |

| M1 to M2b | Crosslinking Fcγ receptors by ICs | [21,53] |

| M1 to M2c | Deficiency in Pellino-1 with IL-10 induction | [10] |

| M2a to M1 | Inhibit STAT6 signaling: (1) PD-1 deficiency; (2) STAT6 deficiency); TLR agonists: (1) TLR7/8 agonist: R848 (resiquimod) (2) TLR3 agonist: poly(I:C); (3) TLR7 agonist: imiquimod | [3,92,93,140,141] |

| M2a to M2b | Exposure to LPS and ICs | [21] |

| M2b to M0/M1 | CCL1 depletion or inhibition | [8,54,56,62] |

| M2b to M2a | PPARƳ ligands | [142] |

| M2d to M1 | IFN-γ exposure | [66,143] |

| M2c to M1 | STAT3 inhibition: corosolic acid | [79] |

| Name | Peptide Sequence | Receptor | Targets | Methods | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NW | NWYLPWLGTNDW | PHB1 | Human DCs, monocytes, M1, M2 | In vitro phage display | [108,109,110] |

| M2pep | YEQDPWGVKWWY | Unknown | Murine bone marrow monocytes derived M1 and M2 | In vitro phage display | [111,112,113,147,149] |

| UNO | CSPGAKVRC | CD206 | Human and murine CD206+ M2 macrophages | In vivo phage display | [90,91,92,107] |

| Melittin | GIGAVLKVLTTGLPAL-ISWIKRKRQQ | Unknown | Human and murine CD206+ M2 macrophages, tumor cells, endothelial cell, red blood cells | Identified from honey bee venom | [89,114,115] |

| LyP-1 | CGNKRTRGC | p32, NRP 1/2 | Tumor lymphatics, tumor cells (i.e., MDA-MB-435), TAMs, atherosclerotic plaque macrophages | In vitro and in vivo phage display | [118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125] |

| RP182 | KFRKAFKRFF | CD206 | Human and murine CD206+ M2 macrophages | In silico biophysical homology screening | [116,117] |

| T4 | NLLMAAS | Tie2 receptor | Tie2 expressing human endothelial cells and TAMs | In vitro phage display | [126,127] |

| CRV | CRVLRSGSC | Retinoid X receptor beta | Murine and human macrophages | In vitro phage display | [130,131] |

| IL4RPep-1 | CRKRLDRNC | IL-4 receptor | IL-4 receptor expressing murine T4 breast cancer cells and TAMs | Ex vivo phage display | [128,129] |

| Pep-20 | AWSATWSNYWRH | CD47 | Myeloid cells (i.e., DCs, monocytes, macrophages) | In vitro phage display | [100] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Sioud, M. Tumor-Associated Macrophage Subsets: Shaping Polarization and Targeting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087493

Zhang Q, Sioud M. Tumor-Associated Macrophage Subsets: Shaping Polarization and Targeting. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(8):7493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087493

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qindong, and Mouldy Sioud. 2023. "Tumor-Associated Macrophage Subsets: Shaping Polarization and Targeting" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 8: 7493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087493

APA StyleZhang, Q., & Sioud, M. (2023). Tumor-Associated Macrophage Subsets: Shaping Polarization and Targeting. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(8), 7493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087493