Coexistence of Retinitis Pigmentosa and Ataxia in Patients with PHARC, PCARP, and Oliver–McFarlane Syndromes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

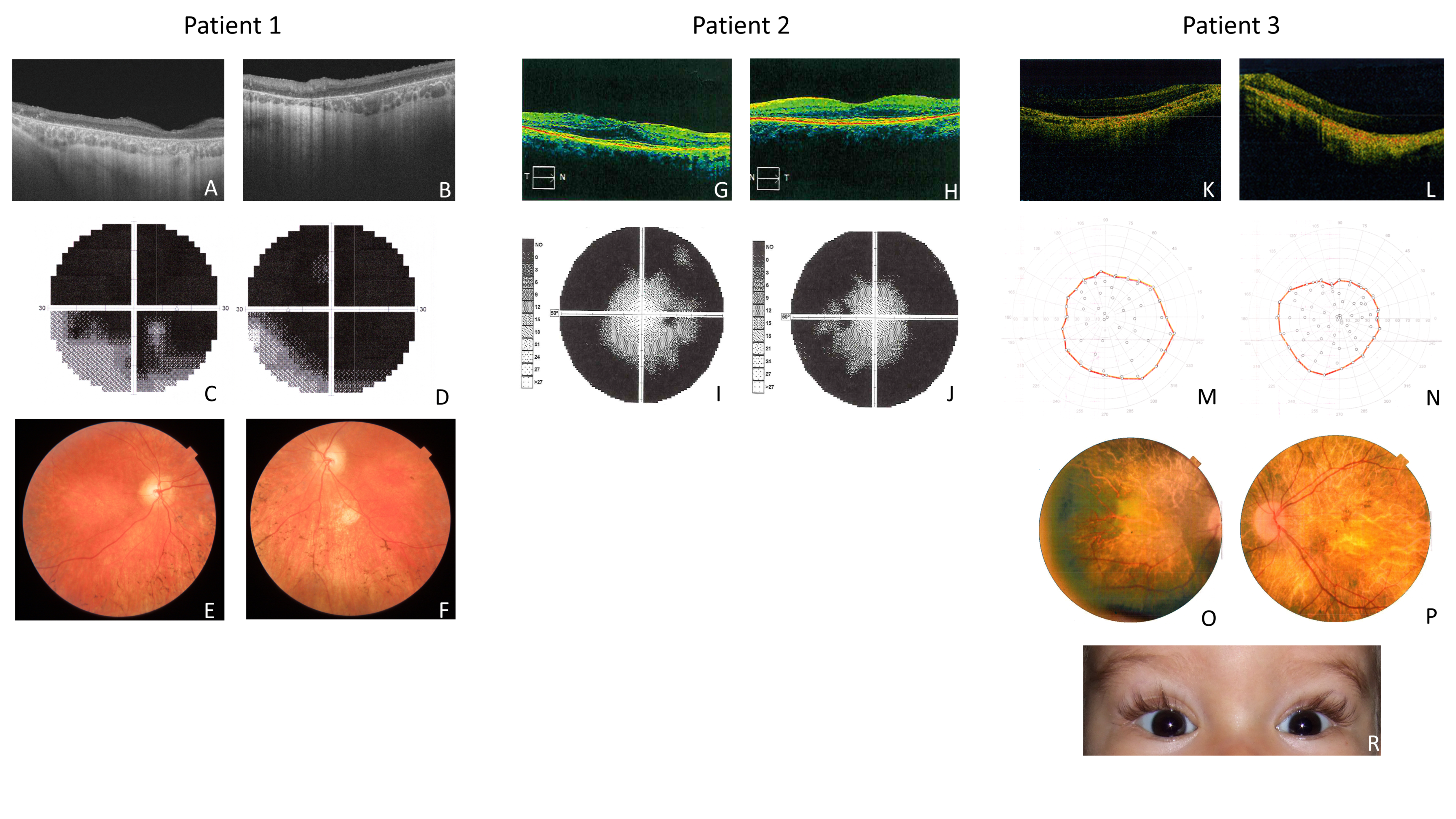

2.1. Clinical Features of Patient 1 (P1)

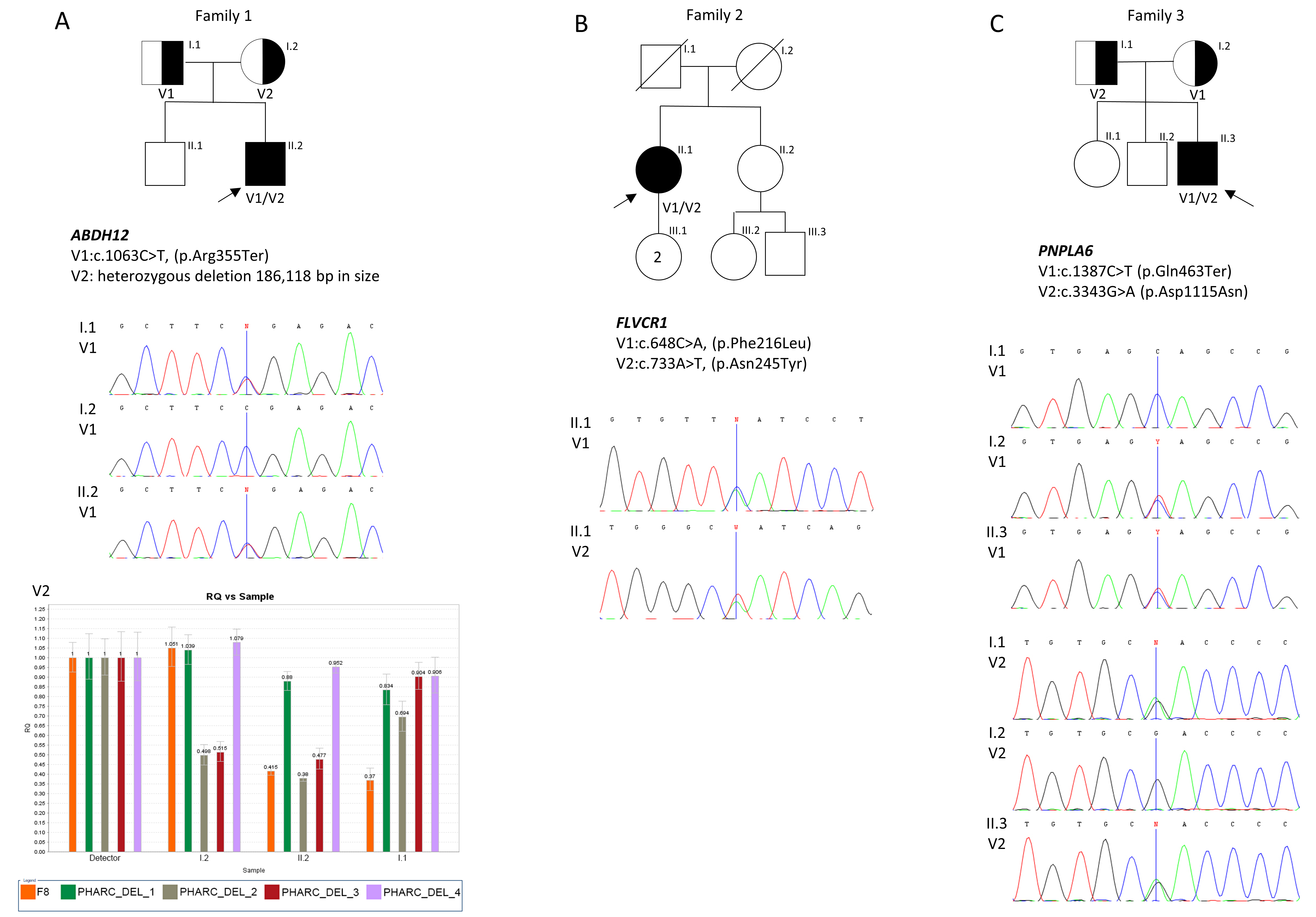

Molecular Results of Patient 1 (P1)

2.2. Clinical Features of Patient 2 (P2)

Molecular Results of Patient 2 (P2)

2.3. Clinical Features of Patient 3 (P3)

Molecular Results of Patient 3 (P3)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Clinical Examination

4.2. Molecular Analyses

4.2.1. Patient 1 (P1)

4.2.2. Patient 2 (P2)

4.2.3. Patient 3 (P3)

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hartong, D.T.; Berson, E.L.; Dryja, T.P. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 2006, 368, 1795–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbakel, S.K.; van Huet, R.A.C.; Boon, C.J.F.; den Hollander, A.I.; Collin, R.W.J.; Klaver, C.C.W.; Hoyng, C.B.; Roepman, R.; Klevering, B.J. Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 66, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiskerstrand, T.; H’mida-Ben Brahim, D.; Johansson, S.; M’zahem, A.; Haukanes, B.I.; Drouot, N.; Zimmermann, J.; Cole, A.J.; Vedeler, C.; Bredrup, C.; et al. Mutations in ABHD12 cause the neurodegenerative disease PHARC: An inborn error of endocannabinoid metabolism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 87, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiguchi, K.M.; Avila-Fernandez, A.; van Huet, R.A.C.; Corton, M.; Pérez-Carro, R.; Martín-Garrido, E.; López-Molina, M.I.; Blanco-Kelly, F.; Hoefsloot, L.H.; van Zelst-Stams, W.A.; et al. Exome sequencing extends the phenotypic spectrum for ABHD12 mutations: From syndromic to nonsyndromic retinal degeneration. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1620–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimm, A.; Rahal, A.; Schoen, U.; Abicht, A.; Klebe, S.; Kleinschnitz, C.; Hagenacker, T.; Stettner, M. Genotype-phenotype correlation in a novel ABHD12 mutation underlying PHARC syndrome. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2020, 25, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiabrando, D.; Bertino, F.; Tolosano, E. Hereditary Ataxia: A Focus on Heme Metabolism and Fe-S Cluster Biogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajadhyaksha, A.M.; Elemento, O.; Puffenberger, E.G.; Schierberl, K.C.; Xiang, J.Z.; Putorti, M.L.; Berciano, J.; Poulin, C.; Brais, B.; Michaelides, M.; et al. Mutations in FLVCR1 cause posterior column ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 87, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiura, H.; Fukuda, Y.; Mitsui, J.; Nakahara, Y.; Ahsan, B.; Takahashi, Y.; Ichikawa, Y.; Goto, J.; Sakai, T.; Tsuji, S. Posterior column ataxia with retinitis pigmentosa in a Japanese family with a novel mutation in FLVCR1. Neurogenetics 2011, 12, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimi, M.; Gershoni-Baruch, R. Autosomal recessive Oliver-McFarlane syndrome: Retinitis pigmentosa, short stature (GH deficiency), trichomegaly, and hair anomalies or CPD syndrome (chorioretinopathy-pituitary dysfunction). Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2005, 138, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufnagel, R.B.; Arno, G.; Hein, N.D.; Hersheson, J.; Prasad, M.; Anderson, Y.; Krueger, L.A.; Gregory, L.C.; Stoetzel, C.; Jaworek, T.J.; et al. Neuropathy target esterase impairments cause Oliver-McFarlane and Laurence-Moon syndromes. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 52, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.-T.; Almushattat, H.; Strubbe, I.; Georgiou, M.; Li, C.H.Z.; van Schooneveld, M.J.; Joniau, I.; De Baere, E.; Florijn, R.J.; Bergen, A.A.; et al. The Phenotypic Spectrum of Patients with PHARC Syndrome Due to Variants in ABHD12: An Ophthalmic Perspective. Genes 2021, 12, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.-H.; Naydenov, A.; Blankman, J.L.; Mefford, H.C.; Davis, M.; Sul, Y.; Barloon, A.S.; Bonkowski, E.; Wolff, J.; Matsushita, M.; et al. Two novel mutations in ABHD12: Expansion of the mutation spectrum in PHARC and assessment of their functional effects. Hum. Mutat. 2013, 34, 1672–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann-Gagescu, R.; Dona, M.; Hetterschijt, L.; Tonnaer, E.; Peters, T.; de Vrieze, E.; Mans, D.A.; van Beersum, S.E.C.; Phelps, I.G.; Keunen, J.E.; et al. The Ciliopathy Protein CC2D2A Associates with NINL and Functions in RAB8-MICAL3-Regulated Vesicle Trafficking. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naharros, I.O.; Gesemann, M.; Mateos, J.M.; Barmettler, G.; Forbes, A.; Ziegler, U.; Neuhauss, S.C.F.; Bachmann-Gagescu, R. Loss-of-function of the ciliopathy protein Cc2d2a disorganizes the vesicle fusion machinery at the periciliary membrane and indirectly affects Rab8-trafficking in zebrafish photoreceptors. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1007150. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, T.; Slim, R.; Mansour, A.; Nauck, M.; Nürnberg, G.; Nürnberg, P.; Decker, C.; Dafinger, C.; Ebermann, I.; Bergmann, C.; et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing identifies a homozygous nonsense mutation in ABHD12, the gene underlying PHARC, in a family clinically diagnosed with Usher syndrome type 3. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2012, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanatori, I.; Yasui, Y.; Miura, K.; Kishi, F. Mutations of FLVCR1 in posterior column ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa result in the loss of heme export activity. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2012, 49, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiabrando, D.; Castori, M.; di Rocco, M.; Ungelenk, M.; Gießelmann, S.; Di Capua, M.; Madeo, A.; Grammatico, P.; Bartsch, S.; Hübner, C.A.; et al. Mutations in the Heme Exporter FLVCR1 Cause Sensory Neurodegeneration with Loss of Pain Perception. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castori, M.; Morlino, S.; Ungelenk, M.; Pareyson, D.; Salsano, E.; Grammatico, P.; Tolosano, E.; Kurth, I.; Chiabrando, D. Posterior column ataxia with retinitis pigmentosa coexisting with sensory-autonomic neuropathy and leukemia due to the homozygous p.Pro221Ser FLVCR1 mutation. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2017, 174, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’neil, E.; Serrano, L.; Scoles, D.; E Cunningham, K.; Han, G.; Chiang, J.; Bennett, J.; Aleman, T.S. Detailed retinal phenotype of Boucher-Neuhäuser syndrome associated with mutations in PNPLA6 mimicking choroideremia. Ophthalmic Genet. 2019, 40, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; De Jesus, O. Refsum Disease; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer, J. Neuropathy, Ataxia, and Retinitis Pigmentosa Syndrome. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2023, 24, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klockgether, T.; Mariotti, C.; Paulson, H.L. Spinocerebellar ataxia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M.; Okazaki, H.; Ohashi, K.; Ogura, M.; Ishibashi, S.; Okazaki, S.; Hirayama, S.; Hori, M.; Matsuki, K.; Yokoyama, S.; et al. Current Diagnosis and Management of Abetalipoproteinemia. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2021, 28, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graef, D.; Ligezka, A.N.; Rezents, J.; Mazza, G.L.; Preston, G.; Schwartz, K.; Krzysciak, W.; Lam, C.; Edmondson, A.C.; Johnsen, C.; et al. Coagulation abnormalities in a prospective cohort of 50 patients with PMM2-congenital disorder of glycosylation. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 139, 107606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, W.; Gil, L.; Hunt, S.E.; Riat, H.S.; Ritchie, G.R.S.; Thormann, A.; Flicek, P.; Cunningham, F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedley, D.; Jacobsen, J.O.B.; Jäger, M.; Köhler, S.; Holtgrewe, M.; Schubach, M.; Siragusa, E.; Zemojtel, T.; Buske, O.J.; Washington, N.L.; et al. Next-generation diagnostics and disease-gene discovery with the Exomiser. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 2004–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient ID/Family | Current Age/ Gender | Ophthalmic Symptoms | Polyneuropathy/Cerebellar Ataxia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Night Blindness/Age | Anterior Segment | Arteriolar Attenuation | Macula | Peripheral Retina | BCVA RE/LE | VF Restriction | ERG Results | Ataxia | Polyneuropathy | ||

| P1/F1 | 33/M | +/13 | - | - | Mild atrophic degenerative changes | Decreased RPE pigmentation | 0.2/0.4 | Mild central scotoma | From decreased (70%, at 19 years) to extinguished (at 30 years) | + | Sensorimotor |

| P2/F2 | 61/F | +/20 | Cataract | + | ERM | Bone-spicules | 0.1/0.4 | Concentric narrowing | ND | + | Severe sensorineural |

| P3/F3 | 15/M | +/2 | - | + | Maculopathy | Bone-spicules | 0.1/0.1 | Concentric narrowing | Extinguished | + | - |

| Patient/ Family | Gene | Transcript | Variant Classification | Pathogenicity Prediction in Protein Level | ACMG Classification |

Allele Frequency

(gnomAD) | Molecular Method of Searching the Variants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | Protein | SIFT | PolyPhen-2 | CADD | ||||||

| P1/F1 | ABHD12 | NM_001042472.3 | c.1063C˃T (rs200536497) NC_000020.11:g[(25317079_25319906)_ (25505369_?)del];[=] | p.Arg355Ter - | - - | - - | D - | Pathogenic - | 0.0000192 - | WES |

| P2/F2 | FLVCR1 | NM_014053.4 | c.648C˃A c.733A˃T | p.Phe216Leu p.Asn245Tyr | D D | LD U | U D | Likely pathogenic Likely pathogenic | - - | WES |

| P3/F3 | PNPLA6 | NM_001166114.2 | c.1387C˃T c.3343G˃A (rs372763461) | p.Gln463Ter p.Asp1115Asn | - D | - LD | D D | Likely pathogenic Likely pathogenic | - 0.0000093 | NGS panel |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wawrocka, A.; Walczak-Sztulpa, J.; Kuszel, L.; Niedziela-Schwartz, Z.; Skorczyk-Werner, A.; Bernardczyk-Meller, J.; Krawczynski, M.R. Coexistence of Retinitis Pigmentosa and Ataxia in Patients with PHARC, PCARP, and Oliver–McFarlane Syndromes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5759. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115759

Wawrocka A, Walczak-Sztulpa J, Kuszel L, Niedziela-Schwartz Z, Skorczyk-Werner A, Bernardczyk-Meller J, Krawczynski MR. Coexistence of Retinitis Pigmentosa and Ataxia in Patients with PHARC, PCARP, and Oliver–McFarlane Syndromes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):5759. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115759

Chicago/Turabian StyleWawrocka, Anna, Joanna Walczak-Sztulpa, Lukasz Kuszel, Zuzanna Niedziela-Schwartz, Anna Skorczyk-Werner, Jadwiga Bernardczyk-Meller, and Maciej R. Krawczynski. 2024. "Coexistence of Retinitis Pigmentosa and Ataxia in Patients with PHARC, PCARP, and Oliver–McFarlane Syndromes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 5759. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115759

APA StyleWawrocka, A., Walczak-Sztulpa, J., Kuszel, L., Niedziela-Schwartz, Z., Skorczyk-Werner, A., Bernardczyk-Meller, J., & Krawczynski, M. R. (2024). Coexistence of Retinitis Pigmentosa and Ataxia in Patients with PHARC, PCARP, and Oliver–McFarlane Syndromes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(11), 5759. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115759