Metagenomic Analysis: Alterations of Soil Microbial Community and Function due to the Disturbance of Collecting Cordyceps sinensis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

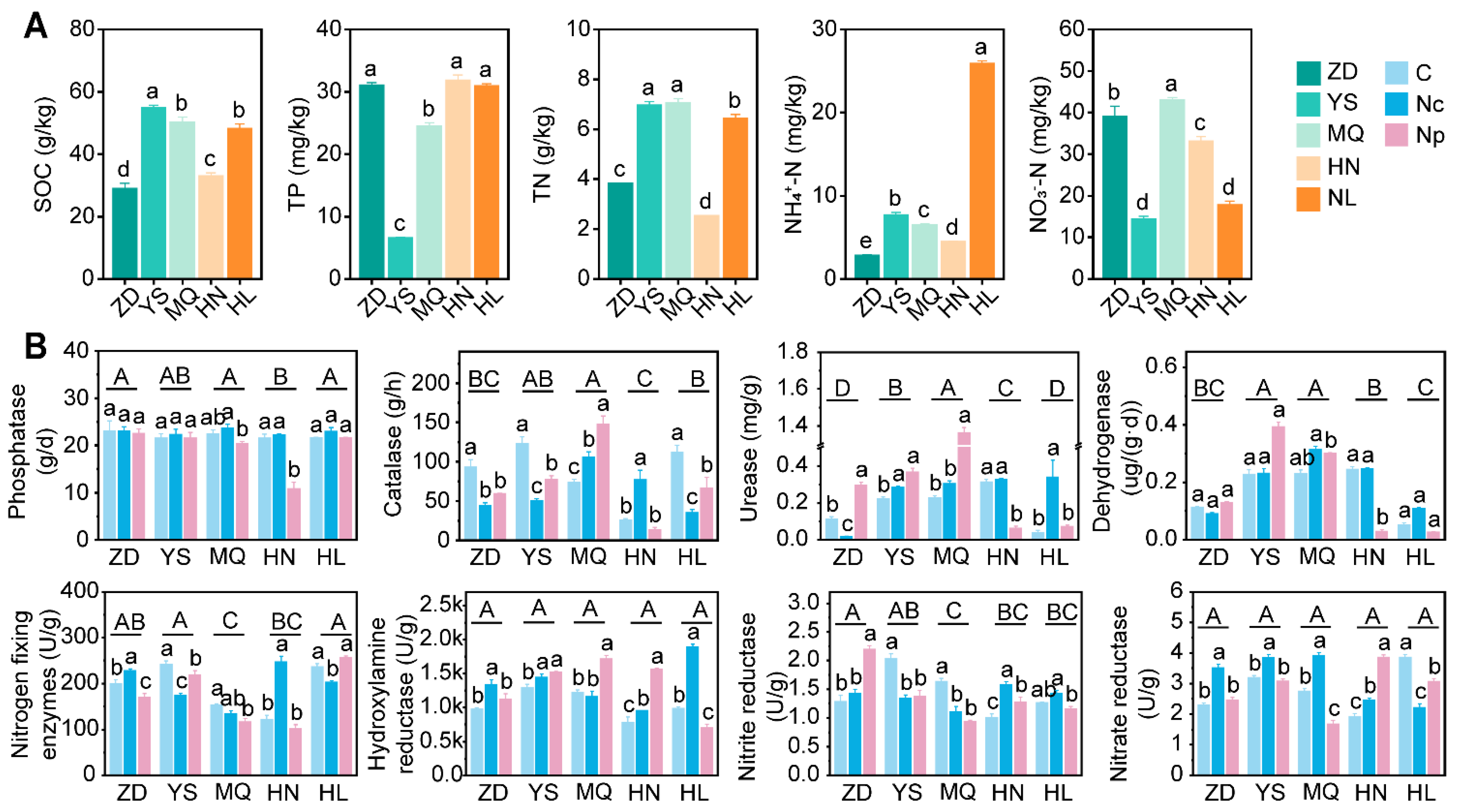

2.1. Soil Nutrients and Enzyme Activity

2.1.1. Soil Nutrients

2.1.2. Soil Enzyme Activity

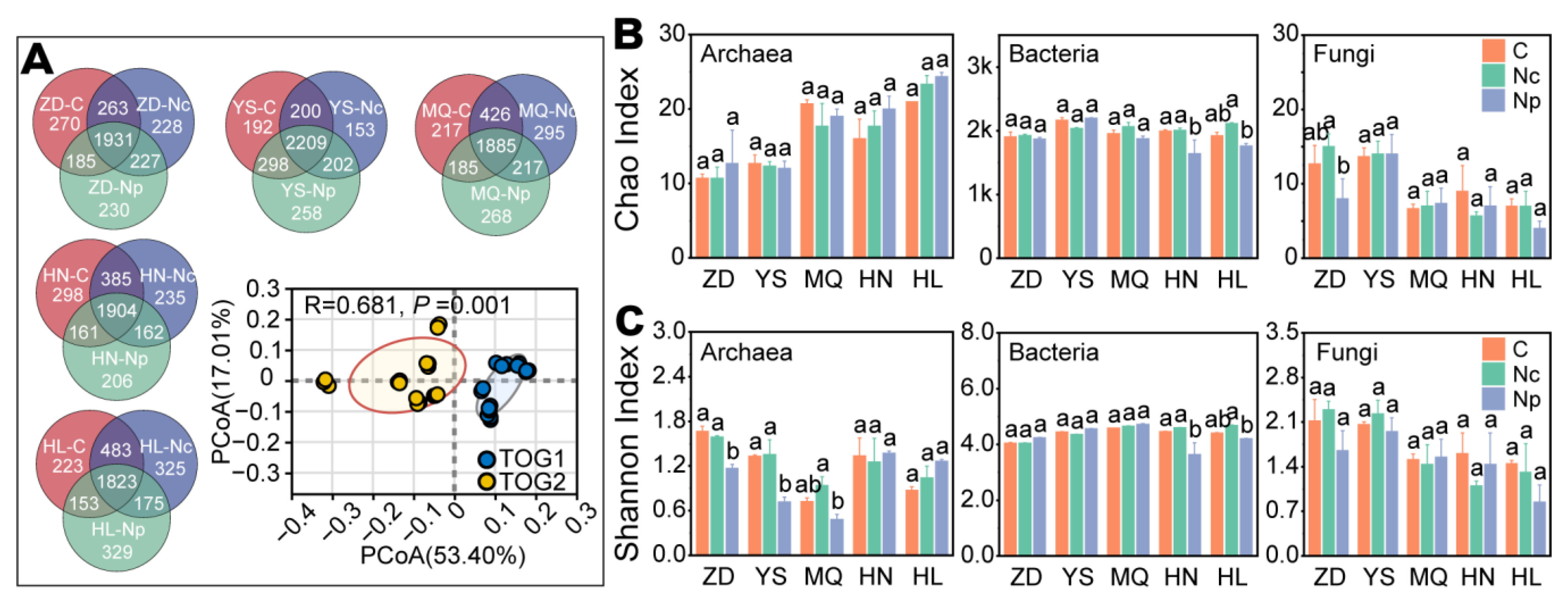

2.2. Soil Microbial Diversity and Community Structure

2.2.1. Sequencing Results and Microbial Diversity

2.2.2. Microbial Community Composition and Structure

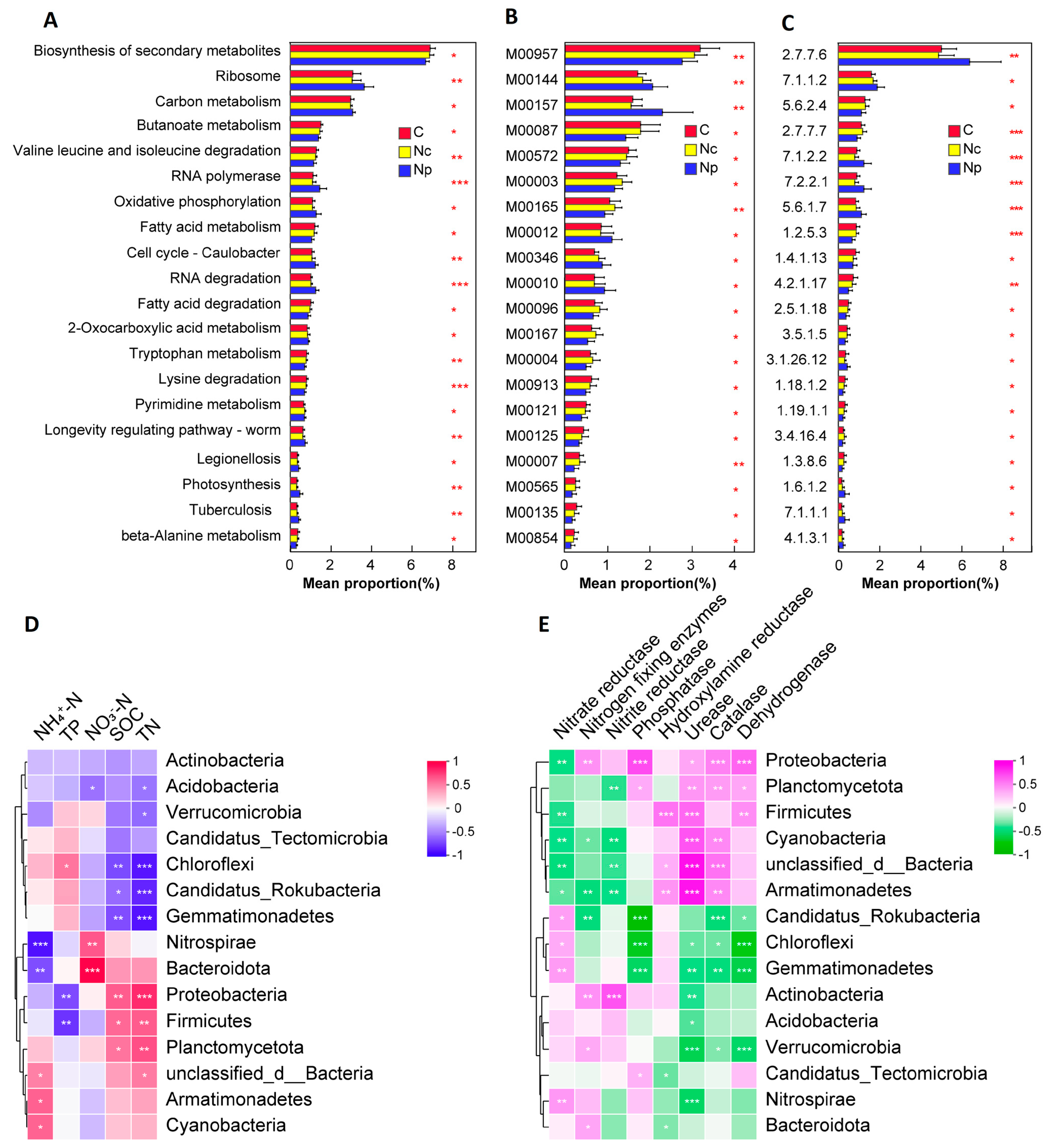

2.3. KEGG Functional Analysis

2.4. Relationships Between Microbial Communities and Environmental Factors

3. Discussion

3.1. Collection of Chinese Cordyceps Altered Soil Nutrients and Enzyme Activity

3.2. Chinese Cordyceps Collection Alters Microbial Composition

3.3. Chinese Cordyceps Collection Affects Microbial Community Functions

3.4. Microorganisms Alter Soil Nutrients and Enzyme Activities

3.5. Patterns of Microbiological Effects of Cordyceps Collection

4. Materials and Methods

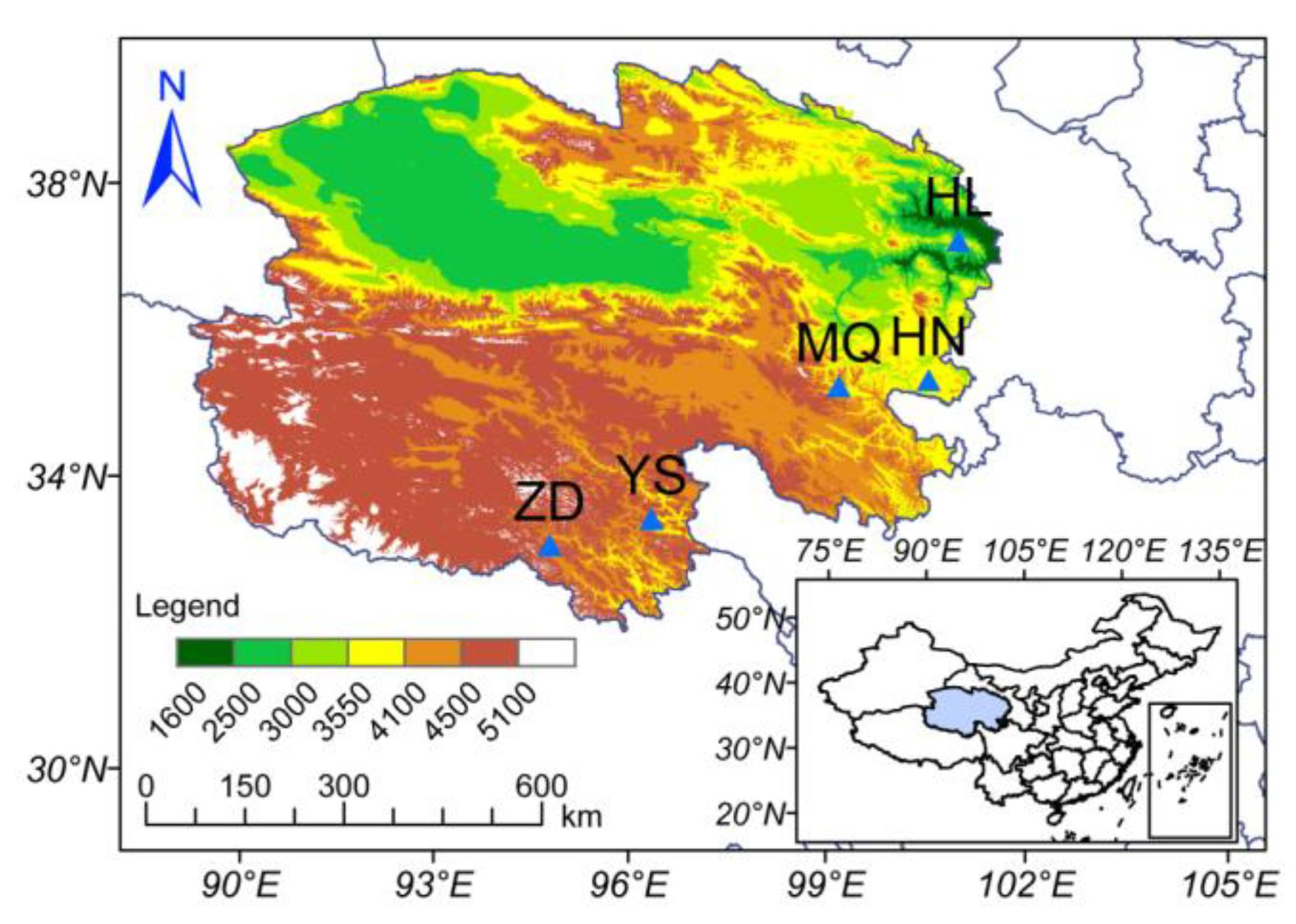

4.1. Field Sites and Sampling

4.1.1. Field Sites

4.1.2. Soil Sample Collection

4.2. Soil Nutrient and Enzyme

4.2.1. Soil Nutrient Measurement

4.2.2. Enzyme Activity Assay

4.3. DNA Extraction and Metagenomic Sequencing

4.4. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Mara, F.P. The role of grasslands in food security and climate change. Ann. Bot. 2012, 110, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, A.B.; Borer, E.T.; Collins, S.L.; DeLancey, L.C.; Fay, P.A.; Hofmockel, K.S.; Leakey, A.D.B.; Mayes, M.A.; Seabloom, E.W.; Walter, C.A.; et al. Soil carbon stocks in temperate grasslands differ strongly across sites but are insensitive to decade-long fertilization. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 28, 1659–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastogeer, K.M.G.; Tumpa, F.H.; Sultana, A.; Akter, M.A.; Chakraborty, A. Plant microbiome–an account of the factors that shape community composition and diversity. Curr. Plant Biol. 2020, 23, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Luo, Q.; Chen, Y.; He, M.; Zhou, L.; Frank, D.; He, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, X. Effects of livestock grazing on grassland carbon storage and release override impacts associated with global climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 25, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, A.; Xu, H.; Su, D.; Han, X. Spatiotemporal variation indicators for vegetation landscape stability and processes monitoring of semiarid grassland coal mine areas. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 33, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqeel, M.; Ran, J.; Hu, W.; Irshad, M.K.; Dong, L.; Akram, M.A.; Eldesoky, G.E.; Aljuwayid, A.M.; Chuah, L.F.; Deng, J. Plant-soil-microbe interactions in maintaining ecosystem stability and coordinated turnover under changing environmental conditions. Chemosphere 2023, 318, 137924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Yan, C.; Wei, W. Grassland Dynamics and the Driving Factors Based on Net Primary Productivity in Qinghai Province, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, W.; Yao, Y.; Pereira, P. The rising human footprint in the Tibetan Plateau threatens the effectiveness of ecological restoration on vegetation growth. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yu, G.; Yang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Han, L. Ecosystem carbon use efficiency in ecologically vulnerable areas in China: Variation and influencing factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1062055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F. Beneficial biofilms for land rehabilitation and fertilization. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2020, 367, fnaa184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frąc, M.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Sitarek, M. Changes in the Mineral Content of Soil following the Application of Different Organic Matter Sources. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Ros, G.H.; Furtak, K.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Soil carbon sequestration—An interplay between soil microbial community and soil organic matter dynamics. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Hu, W.; Zheng, J.; Du, F.; Zhang, X. Estimating soil organic carbon storage and distribution in a catchment of Loess Plateau, China. Geoderma 2010, 154, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Z. Soil physicochemical properties and microorganisms jointly regulate the variations of soil carbon and nitrogen cycles along vegetation restoration on the Loess Plateau, China. Plant Soil 2023, 494, 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macray, J.E.; Montgomery, D.R. Trends in soil organic matter and topsoil thickness under regenerative practices at the University of Washington student farm. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, S.; Yang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, L.; Yan, B.; Yang, X.; Chen, T. Geochemical properties, heavy metals and soil microbial community during revegetation process in a production Pb-Zn tailings. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Qin, F.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, X.; Chen, W.; Huang, Q. Long-term chemical fertilization-driving changes in soil autotrophic microbial community depresses soil CO2 fixation in a Mollisol. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Ji, W.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Kang, Y.; Yao, B. Effects of different management practices on soil microbial community structure and function in alpine grassland. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 327, 116859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.-X.; Yang, L.-H.; Wang, C.-J.; Zhang, C.-H.; Wan, J.-Z. Distribution and Conservation of Plants in the Northeastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau under Climate Change. Diversity 2022, 14, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lü, X.; Li, Y.; Jin, K.; van der Putten, W.H. Soil aggregate microbiomes steer plant community overyielding in ungrazed and intensively grazed grassland soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.X.; Zhang, W.J.; Lang, D.Y.; Zhang, X.J.; Cui, G.C.; Zhang, X.H. Interactions between Endophytes and Plants Beneficial Effect of Endophytes to Ameliorate Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Plants. J. Plant Biol. 2019, 62, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Long, C.; Zhang, H. An authentic assessment method for Cordyceps sinensis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 239, 115879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wu, Z.; Sui, X. Biotransformation of ginsenoside Rb1 with wild Cordyceps sinensis and Ascomycota sp. and its antihyperlipidemic effects on the diet-induced cholesterol of zebrafish. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Niyati, N.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X. Chinese caterpillar fungus (Ophiocordyceps sinensis) in China: Current distribution, trading, and futures under climate change and overexploitation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, C.; Liao, H.; Li, R. Research Progress of Cordyceps sinensis and Its Fermented Mycelium Products on Ameliorating Renal Fibrosis by Reducing Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 2817–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Yang, B.; Leng, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Olatunji, O.J.; Tang, J. Alleviation of Liver Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation Underlines the Protective Effects of Polysaccharides from Cordyceps cicadae on High Sugar/High Fat Diet-Induced Metabolic Syndrome in Rats. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Tan, C.; Ren, J.; Liu, J.; Zou, W.; Liu, G.; Sheng, Y. Cordyceps militaris acidic polysaccharides improve learning and memory impairment in mice with exercise fatigue through the PI3K/NRF2/HO-1 signalling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 227, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Jia, Q.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Preparation of the sphingolipid fraction from mycelia of Cordyceps sinensis and its immunosuppressive activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 291, 115126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenz, E.J.; Bauer, B.A.; Osmundson, T.W.; Motley, T.J. The traditional Chinese medicine Cordyceps sinensis and its effects on apoptotic homeostasis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.-L.; Lai, B.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J.-T.; Hong, Y.-H.; Chen, F.-B.; Tan, S.-Q.; Guo, L.-X. Diversity and Co-Occurrence Patterns of Soil Bacterial and Fungal Communities of Chinese Cordyceps Habitats at Shergyla Mountain, Tibet: Implications for the Occurrence. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, X.; Miao, Y.; Li, M.; Huang, L. Cordyceps cicadae and Cordyceps gunnii have closer species correlation with Cordyceps sinensis: From the perspective of metabonomic and MaxEnt models. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tang, D.; Yu, H. Genomic Comparison of Two Species of Samsoniella with Other Genera in the Family Cordycipitaceae. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Tang, D.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, C.; Yu, H. Microbial community composition and soil metabolism in the coexisting Cordyceps militaris and Ophiocordyceps highlandensis. J. Basic Microbiol. 2022, 62, 1254–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, A.; Xue, K. Cold and humid climates enrich soil carbon stock in the Third Pole grasslands. Innovation 2024, 5, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhan, Z.; Chen, L.; Yan, J.; Qu, R. Vegetation net primary productivity and its response to climate change during 2001–2008 in the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 444, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.L.; Han, Y.J.; Zhang, L.P.; Feng, C.; Wang, M.T. GIS-based ecological climate suitability regionalization for Cordyceps sinensis in Shiqu County, Sichuan Province, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 30, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.B.; Li, X.Z.; Xu, C.T.; Liang, J.; Tang, C.; Wang, T.; He, H.; Cao, Z.F.; Li, Y.L. Soil ecological stoichiometry in the excavated and non-excavated areas of Chinese Cordyceps in Qinghai Province. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2023, 31, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.Q.; Li, X.Z.; Li, Y.L.; Xue, S.Q. Design and implementation of analysis system fot Cordyceps sinensis reserves and suitable zoning of production areas in Qinghai Province. Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 25, 2065–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.-H.; Mai, Z.-H.; Li, C.-J.; Zheng, Q.-Y.; Guo, L.-X. Microbial Diversity Analyses of Fertilized Thitarodes Eggs and Soil Provide New Clues About the Occurrence of Chinese Cordyceps. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, F.; Xu, C.; Luo, S.; Chao, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L. Quantitative assessment of the ecological impact of Chinese cordyceps collection in the typical production areas. Écoscience 2016, 22, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.-X.; Hong, Y.-H.; Zhou, Q.-Z.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, X.-M.; Wang, J.-H. Fungus-larva relation in the formation of Cordyceps sinensis as revealed by stable carbon isotope analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, D.D.; Che, L.L. Response of soil infiltration characteristics to human trampling in Karst Mountain Forests. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 35, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Ren, P. Coupled effect of climate change and human activities on the restoration/degradation of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau grassland. J. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 1299–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanderud, Z.T.; Saurey, S.; Ball, B.A.; Wall, D.H.; Barrett, J.E.; Muscarella, M.E.; Griffin, N.A.; Virginia, R.A.; Barberán, A.; Adams, B.J. Stoichiometric Shifts in Soil C: N: P Promote Bacterial Taxa Dominance, Maintain Biodiversity, and Deconstruct Community Assemblages. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Liu, X.; Xu, H.F.; Li, Y.L. Study on the correlation between soil extract and soil physical and chemical properties of Cordyceps sinensis. Chin. Qinghai J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2017, 47, 29–31+34. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Peng, X.N.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.T.; Dai, K.L.; Xu, H.B.; Dong, L.N.; Zhang, J.C. Seasonal variation characteristics of soil quality in Zijin Mountain under the disturbance of trample. J. Nanjing For. Univ. 2022, 46, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Fierer, N.; Leff, J.W.; Adams, B.J.; Nielsen, U.N.; Bates, S.T.; Lauber, C.L.; Owens, S.; Gilbert, J.A.; Wall, D.H.; Caporaso, J.G. Cross-biome metagenomic analyses of soil microbial communities and their functional attributes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21390–21395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, S.; Guo, J.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Sang, Y. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation on the phytoremediation of PAH-contaminated soil: A meta-analysis. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemanowicz, J.; Brzezińska, M.; Siwik-Ziomek, A.; Koper, J. Activity of selected enzymes and phosphorus content in soils of former sulphur mines. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 134545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.-y.; Wang, M.-w.; Zhu, H.-w.; Guo, Z.-h.; Han, X.-q.; Zeng, P. Response of soil microbial activities and microbial community structure to vanadium stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 142, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Luo, X.; Xiong, X.; Chen, W.; Hao, X.; Huang, Q. Soil Aggregate Stratification of Ureolytic Microbiota Affects Urease Activity in an Inceptisol. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11584–11590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Kong, X.; He, W.; Chen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, Q.; Luo, Y.; Tian, X. Spatiotemporal characteristics of enzymatic hotspots in subtropical forests: In situ evidence from 2D zymography images. Catena 2022, 216, 106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Xue, Y.; Yu, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Fang, J.; Wang, Y.; Adams, J.M.; Hu, Y.; Razavi, B.S. Toxic metal contamination effects mediated by hotspot intensity of soil enzymes and microbial community structure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipahutar, M.K.; Piapukiew, J.; Vangnai, A.S. Efficiency of the formulated plant-growth promoting Pseudomonas fluorescens MC46 inoculant on triclocarban treatment in soil and its effect on Vigna radiata growth and soil enzyme activities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.J.; Beman, J.M.; Eviner, V.T.; Malmstrom, C.M.; Hart, S.C. Soil microbial community structure is unaltered by plant invasion, vegetation clipping, and nitrogen fertilization in experimental semi-arid grasslands. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lee, P.; Lee, G.; Mariko, S.; Oikawa, T. Simulating root responses to grazing of a Mongolian grassland ecosystem. Plant Ecol. 2006, 183, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, N.; Sansupa, C.; Kongsurakan, P.; Sereenonchai, S.; Hatano, R. Soil Microbial Diversity and Community Composition in Rice–Fish Co-Culture and Rice Monoculture Farming System. Biology 2022, 11, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Anderson, I.C.; Singh, B.K. Microbial modulators of soil carbon storage: Integrating genomic and metabolic knowledge for global prediction. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cui, X.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Z.; Yu, Z.; Yao, Q.; Sui, Y.; Jin, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, G. The Diversity and Geographic Distribution of Cultivable Bacillus-Like Bacteria Across Black Soils of Northeast China. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusetti, L.; Aguirre-von-Wobeser, E.; Rocha-Estrada, J.; Shapiro, L.R.; de la Torre, M. Enrichment of Verrucomicrobia, Actinobacteria and Burkholderiales drives selection of bacterial community from soil by maize roots in a traditional milpa agroecosystem. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Chander, P.; George, S. Phylogenetic framework and molecular signatures for the class Chloroflexi and its different clades; proposal for division of the class Chloroflexi class. nov. into the suborder Chloroflexineae subord. nov., consisting of the emended family Oscillochloridaceae and the family Chloroflexaceae fam. nov., and the suborder Roseiflexineae subord. nov., containing the family Roseiflexaceae fam. nov. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2012, 103, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto Moreno, N.; Olthof, A.M.; Svejstrup, J.Q. Transcription-Coupled Nucleotide Excision Repair and the Transcriptional Response to UV-Induced DNA Damage. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2023, 92, 81–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, G.; Srinivasan, S. Involvement of Nucleotide Excision Repair and Rec-Dependent Pathway Genes for UV Radiation Resistance in Deinococcus irradiatisoli 17bor-2. Genes 2023, 14, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, B. Sphingomonas Relies on Chemotaxis to Degrade Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Maintain Dominance in Coking Sites. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fewer, D.P.; Holm, L.; Rouhiainen, L.; Sivonen, K. Atlas of nonribosomal peptide and polyketide biosynthetic pathways reveals common occurrence of nonmodular enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9259–9264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poehlsgaard, J.; Douthwaite, S. The bacterial ribosome as a target for antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Cronan, J.E. α-proteobacteria synthesize biotin precursor pimeloyl-ACP using BioZ 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase and lysine catabolism. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.-R.; Zuo, S.-Q.; Xiao, F.; Guo, F.-Z.; Chen, L.-Y.; Bi, K.; Cheng, D.-Y.; Xu, Z.-N. Advances in biotin biosynthesis and biotechnological production in microorganisms. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasigraf, O.; Kool, D.M.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Sinninghe Damsté, J.S.; Ettwig, K.F.; Parales, R.E. Autotrophic Carbon Dioxide Fixation via the Calvin-Benson-Bassham Cycle by the Denitrifying Methanotroph “Candidatus Methylomirabilis oxyfera”. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2451–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Lü, C.; Xia, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiao, N.; Xun, L.; Liu, J.; Bahn, Y.-S. Synechococcus sp. Strain PCC7002 Uses Sulfide:Quinone Oxidoreductase To Detoxify Exogenous Sulfide and To Convert Endogenous Sulfide to Cellular Sulfane Sulfur. mBio 2020, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, D.; Zeng, H.; Zhao, S.; Chen, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; et al. Diversity and Contributions to Nitrogen Cycling and Carbon Fixation of Soil Salinity Shaped Microbial Communities in Tarim Basin. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zheng, J.; Pan, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Rolf, T. Changes in microbial community structure and function within particle size fractions of a paddy soil under different long-term fertilization treatments from the Tai Lake region, China. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2007, 58, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Nie, C.; Liu, Y.; Du, W.; He, P. Soil microbial community composition closely associates with specific enzyme activities and soil carbon chemistry in a long-term nitrogen fertilized grassland. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z. Soil Enzyme and Its Research Method; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Cheng, X.; Xu, J.; Wu, J.; Chan, L.L.; Cai, Z.; Zhou, J. Dynamic patterns of carbohydrate metabolism genes in bacterioplankton during marine algal blooms. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 286, 127785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivian, D.; Jungbluth, S.P.; Dehal, P.S.; Wood-Charlson, E.M.; Canon, R.S.; Allen, B.H.; Clark, M.M.; Gu, T.; Land, M.L.; Price, G.A.; et al. Metagenome-assembled genome extraction and analysis from microbiomes using KBase. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 18, 208–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Yan, R.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, H.; Liu, G.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Z. Integrated microbiological and metabolomics analyses to understand the mechanism that allows modified biochar to affect the alkalinity of saline soil and winter wheat growth. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Malik, K.; Li, C. Metagenomic Analysis: Alterations of Soil Microbial Community and Function due to the Disturbance of Collecting Cordyceps sinensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252010961

Chen Y, Chen Z, Li X, Malik K, Li C. Metagenomic Analysis: Alterations of Soil Microbial Community and Function due to the Disturbance of Collecting Cordyceps sinensis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(20):10961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252010961

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yangyang, Zhenjiang Chen, Xiuzhang Li, Kamran Malik, and Chunjie Li. 2024. "Metagenomic Analysis: Alterations of Soil Microbial Community and Function due to the Disturbance of Collecting Cordyceps sinensis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 20: 10961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252010961

APA StyleChen, Y., Chen, Z., Li, X., Malik, K., & Li, C. (2024). Metagenomic Analysis: Alterations of Soil Microbial Community and Function due to the Disturbance of Collecting Cordyceps sinensis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(20), 10961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252010961