OsOFP6 Overexpression Alters Plant Architecture, Grain Shape, and Seed Fertility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. T-DNA Insertion Co-Segregates with the Osofp6-D Mutant

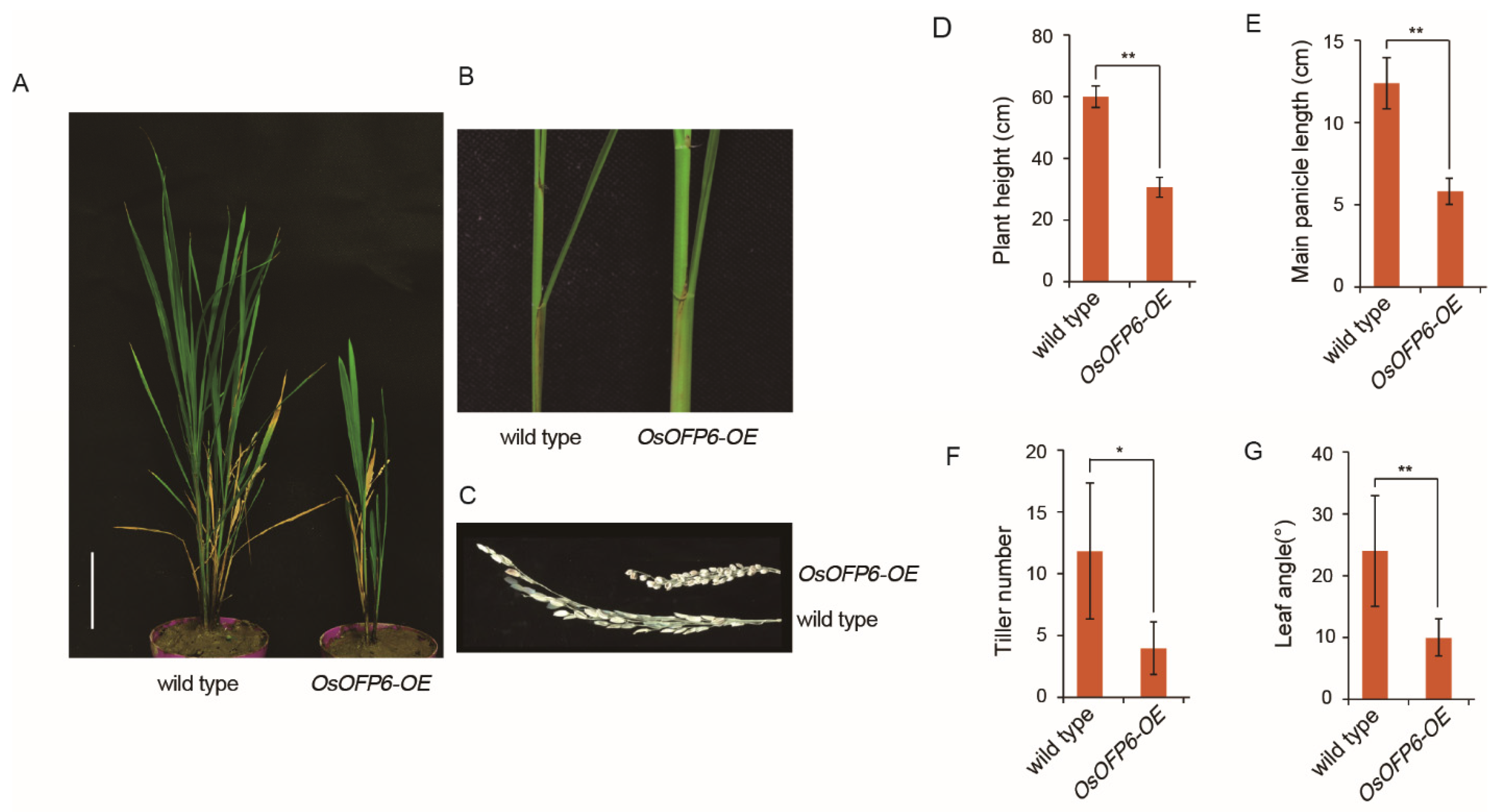

2.2. Overexpression of OsOFP6 Alters Plant Architecture and Grain Shape

2.3. Overexpression of OsOFP6 Affects the Seed Setting Rate and Seed Germination

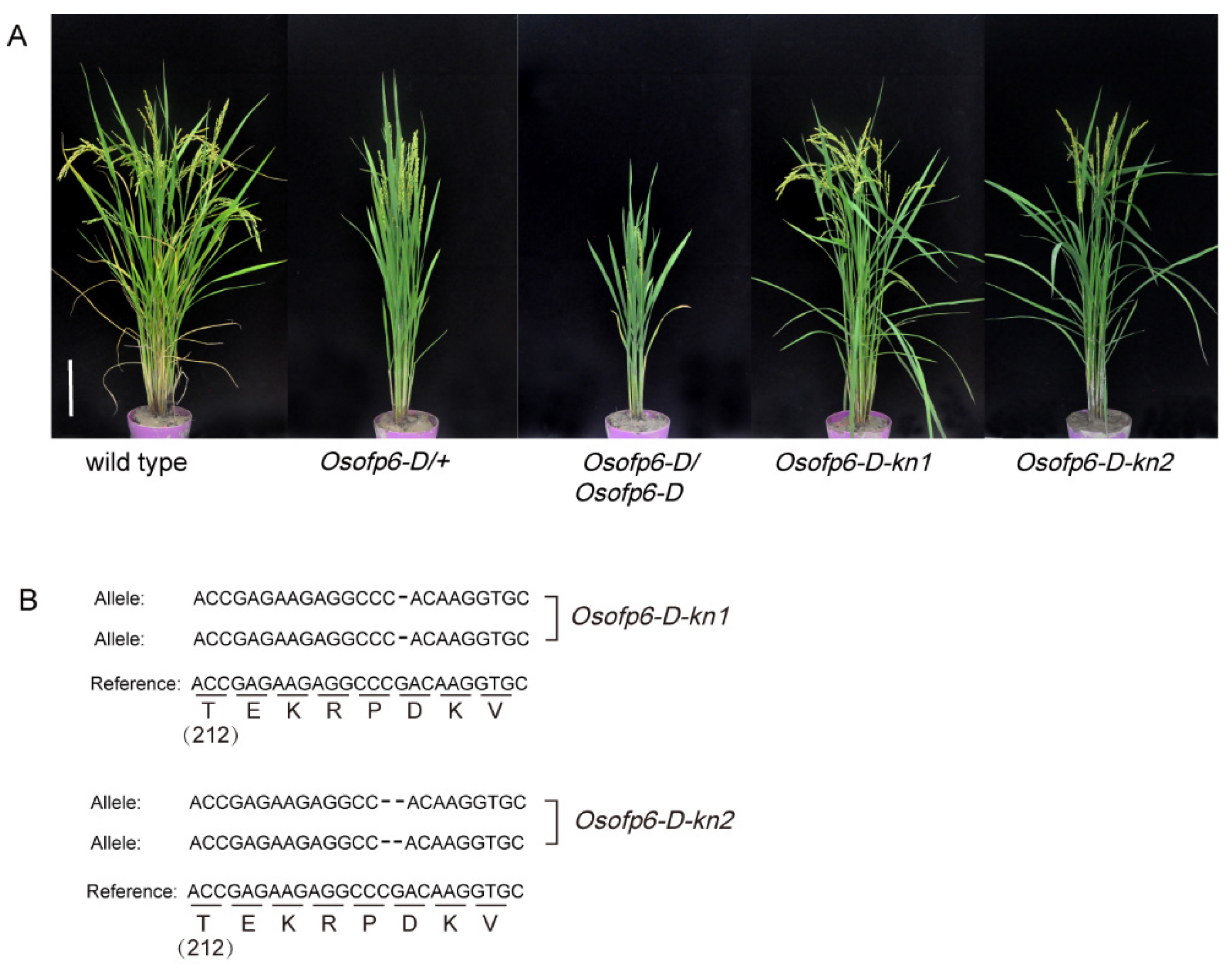

2.4. Functional Verification of OsOFP6

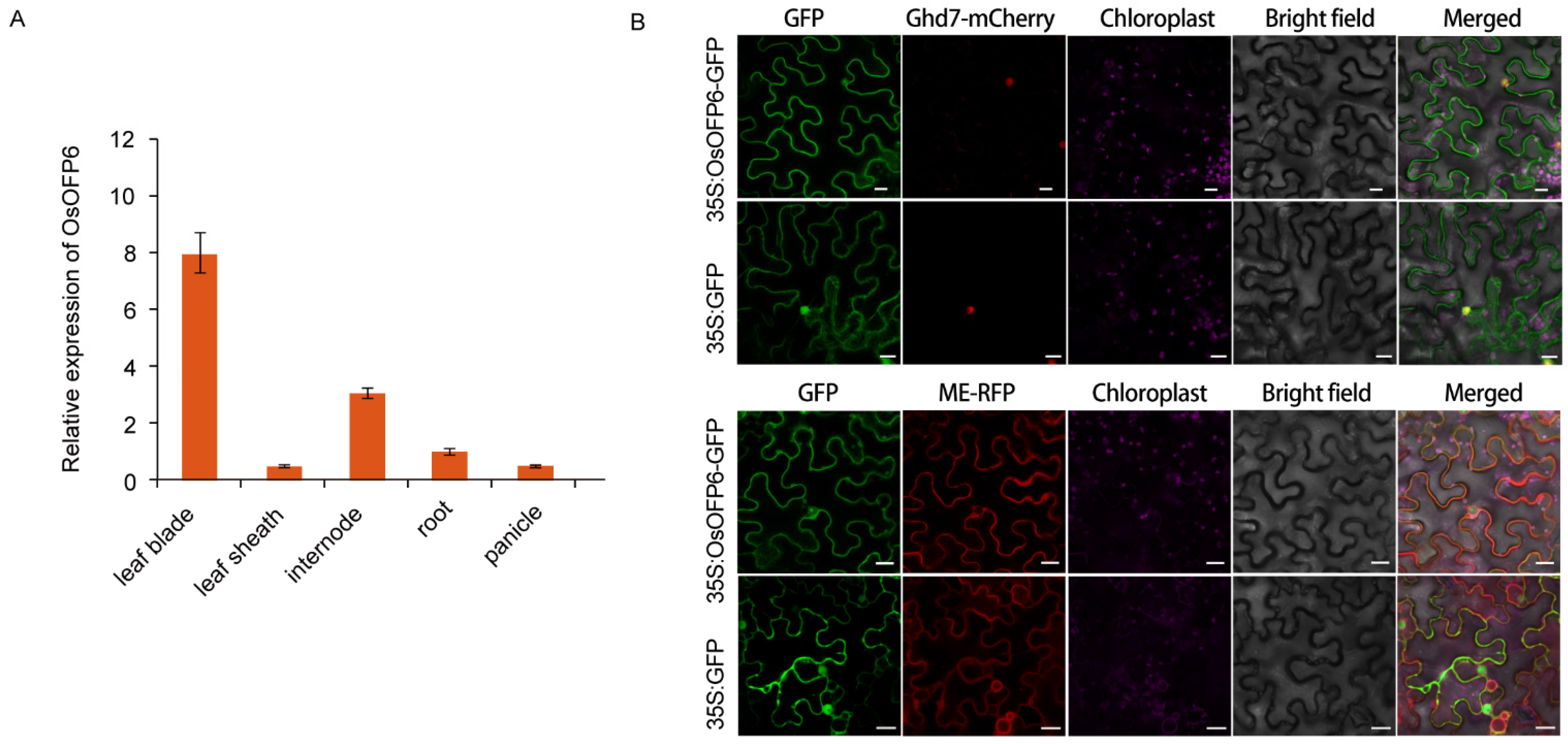

2.5. Expression Pattern of OsOFP6 and Subcellular Localization of OsOFP6

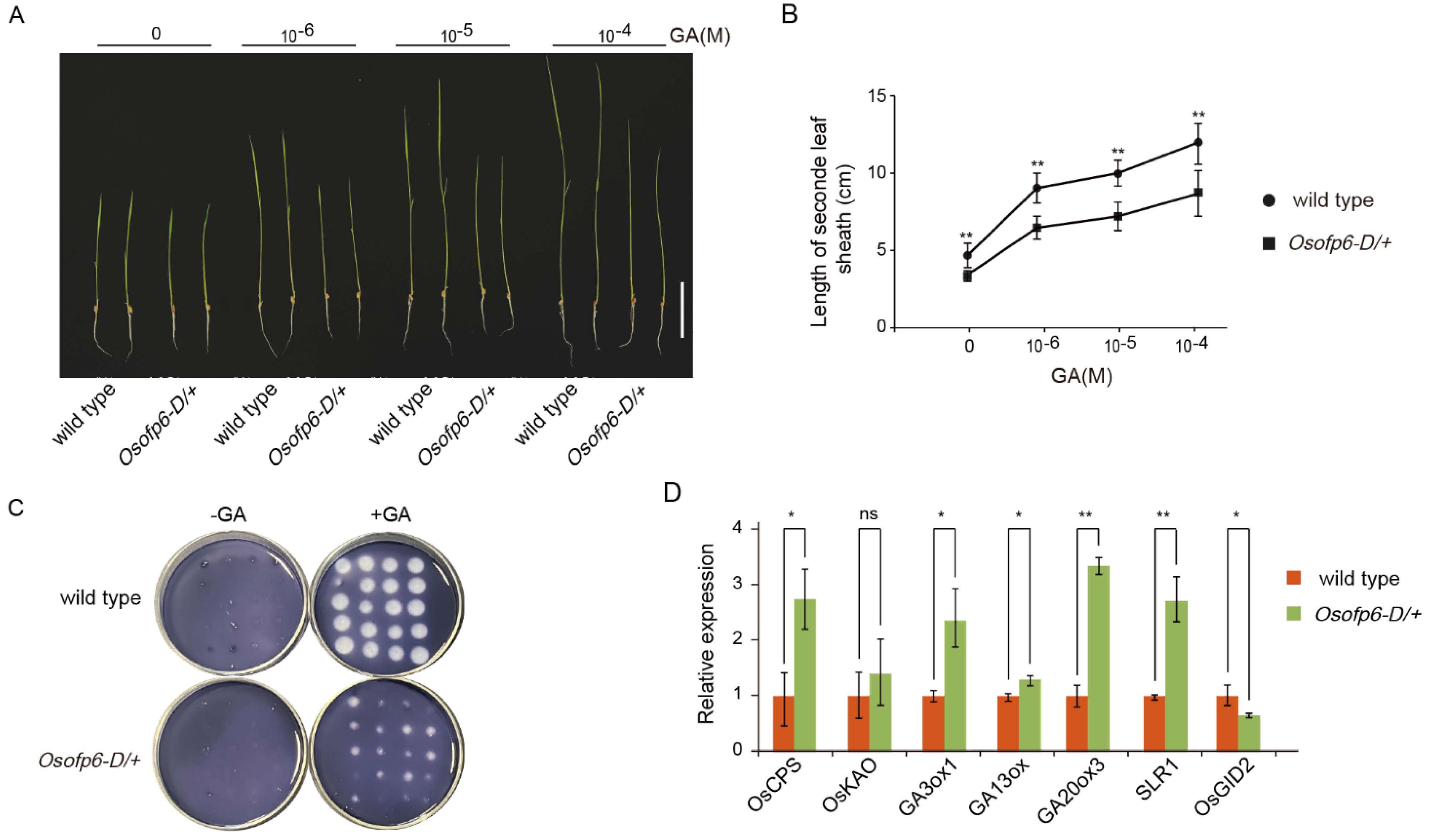

2.6. Plants Overexpressing OsOFP6 Display Less Sensitivity to GA

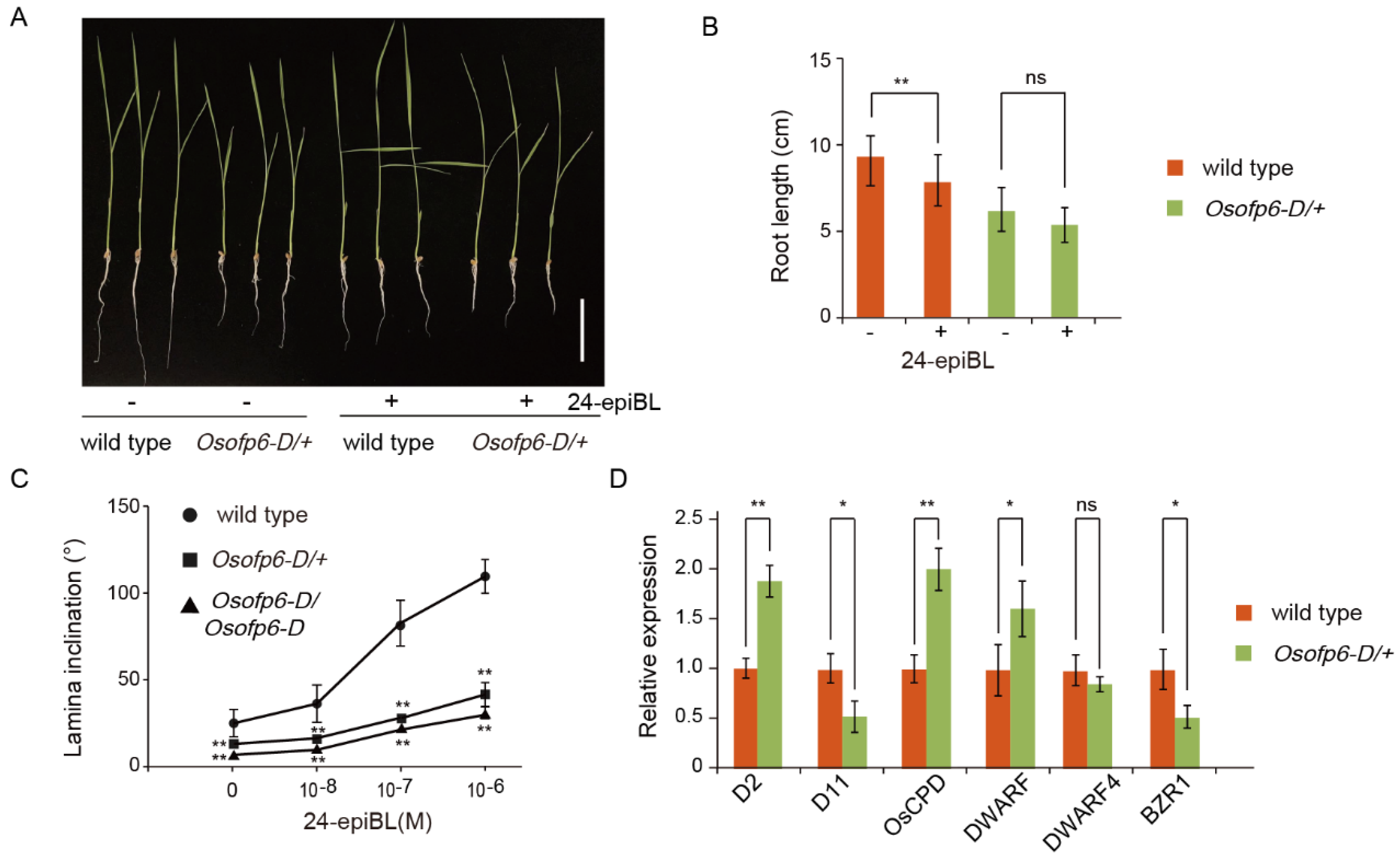

2.7. Plants Overexpressing OsOFP6 Display Less Sensitivity to BR

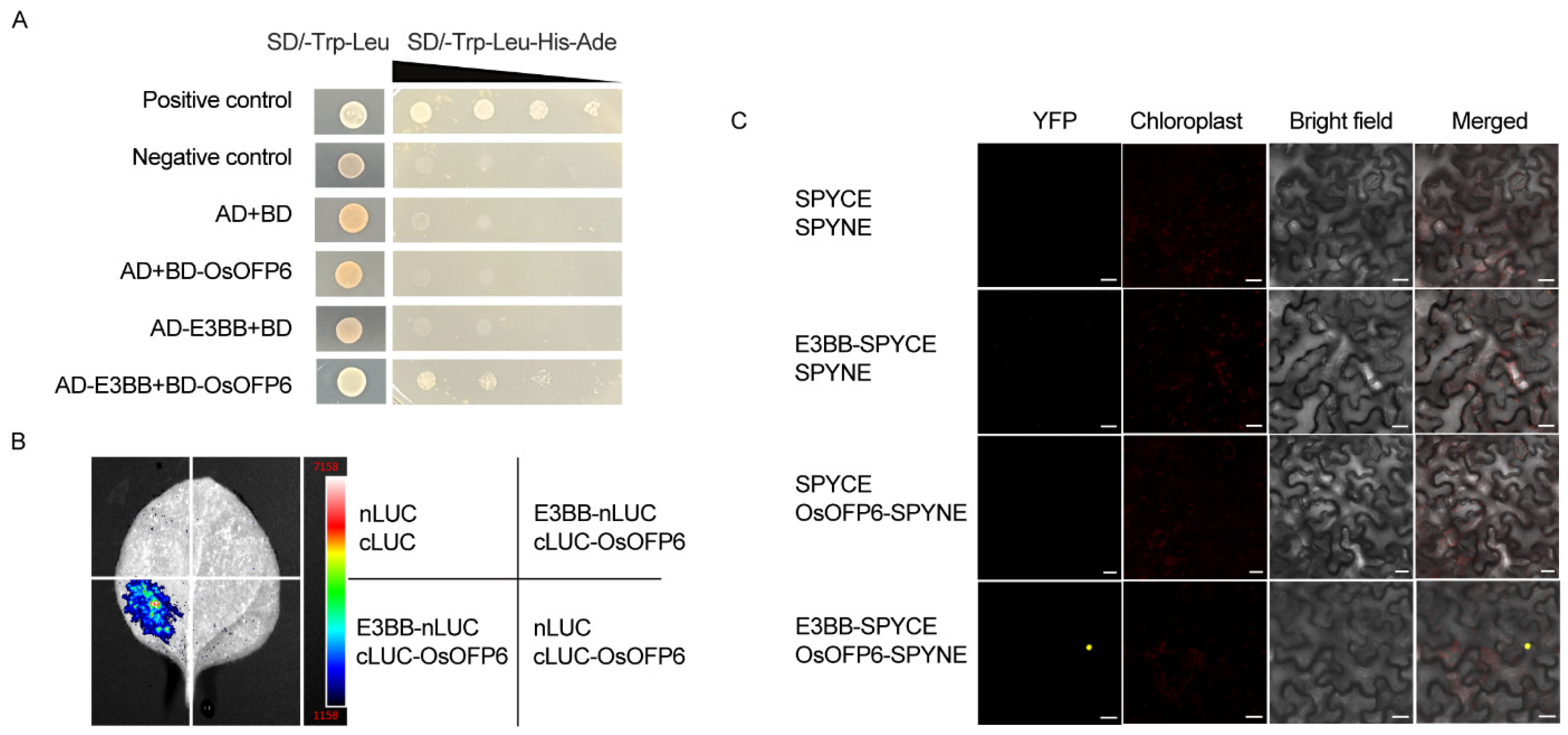

2.8. OsOFP6 Physically Interacts with E3BB

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Phenotypic Analysis

4.2. TAIL-PCR

4.3. Vector Construction and Rice Transformation

4.4. DNA Extraction and PCR

4.5. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

4.6. Phenotypic Evaluation and Cellular Analysis

4.7. Pollen Vitality Staining Experiments

4.8. Subcellular Localization

4.9. Seed Germination Trials

4.10. GA3 Treatment

4.11. BR Treatment

4.12. Protein Interaction Experiments

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, D.; Sun, W.; Yuan, Y.W.; Zhang, N.; Hayward, A.; Liu, Y.L.; Wang, Y. Phylogenetic analyses provide the first insights into the evolution of OVATE family proteins in land plants. Ann. Bot.-Lond. 2014, 113, 1219–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.P.; Van Eck, J.; Cong, B.; Tanksley, S.D. A new class of regulatory genes underlying the cause of pear-shaped tomato fruit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13302–13306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chang, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, J.G. Arabidopsis Ovate Family Protein 1 is a transcriptional repressor that suppresses cell elongation. Plant J. 2007, 50, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.C.; Chang, Y.; Guo, J.J.; Zeng, Q.N.; Ellis, B.E.; Chen, J.G. Arabidopsis Ovate Family Proteins, a Novel Transcriptional Repressor Family, Control Multiple Aspects of Plant Growth and Development. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shen, W.J.; He, Y.; Tian, Z.H.; Li, J.X. OVATE Family Protein 8 Positively Mediates Brassinosteroid Signaling through Interacting with the GSK3-like Kinase in Rice. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.H.; Liu, D.P.; Zhang, G.X.; Tong, H.N.; Chu, C.C. Brassinosteroids Regulate OFP1, a DLT Interacting Protein, to Modulate Plant Architecture and Grain Morphology in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Ma, Y.M.; He, Y.; Tian, Z.H.; Li, J.X. OsOFP19 modulates plant architecture by integrating the cell division pattern and brassinosteroid signaling. Plant J. 2018, 93, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.H.; Zhang, G.X.; Liu, D.P.; Niu, M.; Tong, H.N.; Chu, C.C. GSK2 stabilizes OFP3 to suppress brassinosteroid responses in rice. Plant J. 2020, 102, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Y.; Yu, H.; Jiang, W.Z.; Li, H.Y.; Wu, T.; Chu, J.F.; Xin, P.Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, R.; Zhou, T.; et al. Overexpression of ovate family protein 22 confers multiple morphological changes and represses gibberellin and brassinosteroid signalings in transgenic rice. Plant Sci. 2021, 304, 110734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.J.; Begcy, K.; Sarath, G.; Walia, H. Rice Ovate Family Protein 2 (OFP2) alters hormonal homeostasis and vasculature development. Plant Sci. 2015, 241, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.G.; Sun, L.L.; Zhang, X.F.; Zhang, S.Q.; Xie, D.W.; Liang, C.B.; Huang, W.G.; Fan, L.J.; Fang, Y.Y.; Chang, Y. OFP1 Interaction with ATH1 Regulates Stem Growth, Flowering Time and Flower Basal Boundary Formation in Arabidopsis. Genes 2018, 9, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.M.; Yang, C.; He, Y.; Tian, Z.H.; Li, J.X. Rice OVATE family protein 6 regulates plant development and confers resistance to drought and cold stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 4885–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.G.; Cheng, X.; Li, F.F.; Feng, P.P.; Hu, G.L.; Chen, G.P.; Xie, Q.L.; Hu, Z.L. Overexpression of SlOFP20 in Tomato Affects Plant Growth, Chlorophyll Accumulation, and Leaf Senescence. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.G.; Hu, Z.L.; Li, F.F.; Tian, S.B.; Zhu, Z.G.; Li, A.Z.; Chen, G.P. Overexpression of SlOFP20 affects floral organ and pollen development. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.X.; Ma, Y.M.; Yang, C.; Li, J.X. Rice OVATE family protein 6 regulates leaf angle by modulating secondary cell wall biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 104, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Shen, L.; Fu, Y.P.; Yan, C.J.; Wang, K.J. A Simple CRISPR/Cas9 System for Multiplex Genome Editing in Rice. J. Genet. Genom. 2015, 42, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disch, S.; Anastasiou, E.; Sharma, V.K.; Laux, T.; Fletcher, J.C.; Lenhard, M. The E3 ubiquitin ligase BIG BROTHER controls Arabidopsis organ size in a dosage-dependent manner. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Jiang, W.Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Piao, M.X.; Chen, Z.D.; Bian, M.D. Expression Pattern and Subcellular Localization of the Ovate Protein Family in Rice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, H.N.; Xiao, Y.H.; Liu, D.P.; Gao, S.P.; Liu, L.C.; Yin, Y.H.; Jin, Y.; Qian, Q.; Chu, C.C. Brassinosteroid Regulates Cell Elongation by Modulating Gibberellin Metabolism in Rice. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 4376–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, M.Y.; Shang, J.X.; Oh, E.; Fan, M.; Bai, Y.; Zentella, R.; Sun, T.P.; Wang, Z.Y. Brassinosteroid, gibberellin and phytochrome impinge on a common transcription module in Arabidopsis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Bartolome, J.; Minguet, E.G.; Grau-Enguix, F.; Abbas, M.; Locascio, A.; Thomas, S.G.; Alabadi, D.; Blazquez, M.A. Molecular mechanism for the interaction between gibberellin and brassinosteroid signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13446–13451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Nakano, T.; Gendron, J.; He, J.X.; Chen, M.; Vafeados, D.; Yang, Y.L.; Fujioka, S.; Yoshida, S.; Asami, T.; et al. Nuclear-localized BZR1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced growth and feedback suppression of brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Dev. Cell 2002, 2, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.Y.; Li, J. Regulation of Brassinosteroid Homeostasis in Higher Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 583622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xie, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, J. Regulatory networks of the F-box protein FBX206 and OVATE family proteins modulate brassinosteroid pathway to regulate grain size and yield in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 75, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Wang, H.R.; Yin, W.C.; Meng, W.J.; Xiao, Y.H.; Liu, D.P.; Zhang, X.X.; Dong, N.N.; Liu, J.H.; Yang, Y.Z.; et al. Rice DWARF AND LOW-TILLERING and the homeodomain protein OSH15 interact to regulate internode elongation via orchestrating brassinosteroid signaling and metabolism. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3754–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, M.; Yu, J.W.; Wang, J.D.; Gao, Q.; Huang, L.C.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.Q.; Fan, X.L.; Zhao, D.S.; Liu, Q.Q.; et al. Brassinosteroids regulate rice seed germination through the BZR1-RAmy3D transcriptional module. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuninger, H.; Lenhard, M. Expression of the central growth regulator BIG BROTHER is regulated by multiple cis-elements. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhaeren, H.; Chen, Y.; Vermeersch, M.; De Milde, L.; De Vleeschhauwer, V.; Natran, A.; Persiau, G.; Eeckhout, D.; De Jaeger, G.; Gevaert, K.; et al. UBP12 and UBP13 negatively regulate the activity of the ubiquitin-dependent peptidases DA1, DAR1 and DAR2. Elife 2020, 9, e52276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.Z.; Fu, Y.P.; Hu, G.C.; Si, H.M.; Zhu, L.; Wu, C.; Sun, Z.X. Identification and fine mapping of a thermo-sensitive chlorophyll deficient mutant in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Planta 2007, 226, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.G.; Mitsukawa, N.; Oosumi, T.; Whittier, R.F. Efficient Isolation and Mapping of Arabidopsis-Thaliana T-DNA Insert Junctions by Thermal Asymmetric Interlaced Pcr. Plant J. 1995, 8, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Fu, Y.P.; Hu, G.C.; Si, H.M.; Cheng, S.H.; Liu, W.Z. Isolation and characterization of a rice mutant with narrow and rolled leaves. Planta 2010, 232, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, M.K.; Aravindan, S.; Ngangkham, U.; Shubudhi, H.N.; Bag, M.K.; Adak, T.; Munda, S.; Samantaray, S.; Jena, M. Use of molecular markers in identification and characterization of resistance to rice blast in India. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176236. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.G.; Park, S.; Matsuoka, M.; An, G.H. White-core endosperm in rice is generated by knockout mutations in the C-type pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase gene (OsPPDKB). Plant J. 2005, 42, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.C.; Yang, L.; Deng, Q.M.; Wang, S.Q.; Wu, F.Q.; Li, P. Phenotypic characterization of a female sterile mutant in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2006, 48, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.L.; Ishak, A.; Yu, J.; Zhao, R.Y.; Zhao, L.J. Identification and Functional Analysis of Three MAX2 Orthologs in Chrysanthemum. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2013, 55, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Xue, H.W. Rice early flowering1, a CKI, phosphorylates DELLA protein SLR1 to negatively regulate gibberellin signalling. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 1916–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka, M.; Fujisawa, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Ashikari, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Kitano, H.; Matsuoka, M. Rice dwarf mutant d1, which is defective in the alpha subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein, affects gibberellin signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 11638–11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Mei, E.Y.; Tian, X.J.; He, M.L.; Tang, J.Q.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.L.; Song, L.; Li, X.F.; Wang, Z.Y.; et al. regulates grain size and leaf angle in rice through the OsMKK4-OsMAPK6-OsWRKY53 signaling pathway. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 2043–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waadt, R.; Kudla, J. In Planta Visualization of Protein Interactions Using Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC). CSH Protoc. 2008, pdb.prot4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Feng, Y.; Bao, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, F. OsOFP6 Overexpression Alters Plant Architecture, Grain Shape, and Seed Fertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25052889

Zhu X, Li Y, Zhao X, Feng Y, Bao Z, Liu W, Li F. OsOFP6 Overexpression Alters Plant Architecture, Grain Shape, and Seed Fertility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(5):2889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25052889

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Xuting, Yuan Li, Xiangqian Zhao, Yukai Feng, Zhengkai Bao, Wenzhen Liu, and Feifei Li. 2024. "OsOFP6 Overexpression Alters Plant Architecture, Grain Shape, and Seed Fertility" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 5: 2889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25052889

APA StyleZhu, X., Li, Y., Zhao, X., Feng, Y., Bao, Z., Liu, W., & Li, F. (2024). OsOFP6 Overexpression Alters Plant Architecture, Grain Shape, and Seed Fertility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(5), 2889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25052889