Abstract

Anthocyanin synthetase (ANS), a key enzyme in the final step of the anthocyanin synthesis pathway, catalyzes the conversion of leucoanthocyanidins to anthocyanins. In this study, an ANS structural protein (TRINITY_DN18024_c0_g1) was found to be associated with anthocyanin accumulation in Acer pseudosieboldianum leaves, named ApsANS. Real-time quantitative fluorescence PCR analysis revealed that the expression of ApsANS was significantly higher in red-leaved (variant) than green-leaved (wild-type) strains, which was consistent with the transcriptome data. The UPLC results showed that the cyanidin metabolites may be the key substance influencing the final color formation of Acer pseudosieboldianum. The ApsANS gene was cloned and analyzed through bioinformatics analysis. ApsANS has a total length of 1371 bp, and it encodes 360 amino acids. Analysis of the structural domain of the ApsANS protein revealed that ApsANS contains a PcbC functional domain. Protein secondary structure predictions indicate that α-helix, irregularly coiled, and extended chains are the major building blocks. Subcellular localization predicted that ApsANS might be localized in the nucleus. The phylogenetic tree revealed that ApsANS is relatively closely related to ApANS in Acer palmatum. The prediction of miRNA showed that the ApsANS gene is regulated by miR6200. This study provides a theoretical reference for further analyzing the regulatory mechanism of leaf color formation in Acer pseudosieboldianum.

1. Introduction

Anthocyanidins are important products in the flavonoid metabolic pathway that determine the color of most angiosperm tissues, such as flowers, leaves, fruits, and episperm [,]. Anthocyanins are natural water-soluble plant pigments that not only enhance the color of plants but also show many bioactive properties, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer activities [,]. The precursor of anthocyanin biosynthesis is phenylalanine, which is catalyzed by a series of enzymes to produce anthocyanins [], and the key enzymes involved in this process include phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (C4H), chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone-3-hydroxylase (F3H), dihydroflavonol-4-reductase (DFR), and anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) [,,]. ANS is one of the important downstream enzymes, and it catalyzes the conversion of leucoanthocyanidins into colored anthocyanins. It was first isolated from a Zea mays mutant by using transposon tagging and subsequently isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana [,], Malus pumila [], Vitis vinifera [], Litchi chinensis [], Mangifera indica [], Camellia sinensis [], Hosta plantaginea (Lam.) [], Dioscorea opposite, and Punica granatum L. [,]. It has been shown that overexpression of the anthocyanin synthase gene StANS can promote anthocyanin accumulation in potato tubers []. It was reported that the anthocyanin and chlorophyll contents in Arabidopsis lines with the lowest ANS expression levels were lower []. It has been found that the expression of ANS iso-structural genes correlates well with fruit coloration and anthocyanin accumulation []. Previous studies on ANS have focused more on the flower or fruit color of horticultural plants but less on woody foliage plants; consequently, the characteristics and expression of ANS in foliage plants remain unclear [,].

Ornamental plants are an important part of agriculture and horticulture []. Among them, leaf color is one of the most important ornamental features []. Some studies have shown that the change in leaf color of colorful ornamental plants is related to the synthesis and accumulation of anthocyanin in the leaves [,]. Acer refers to the genus Acer in the family Aceraceae, and, as an important ornamental tree species, it is found in Asia, Europe, North America, and the northern edge of Africa [,,]. China is the main distribution area of Acer species, with more than 150 species of germplasm resources, accounting for more than half of the world’s Acer resources []. Acer species are mostly arbors, which are widely used in the timber industry due to their tall, straight trunks []. Acer also has medicinal value, and the extracts from different tissues of the Acer tree contain a wealth of nutrients, such as amino acids, fatty acids, and minerals, and some key physiological active substances, such as triterpenes, chlorogenic acid, and neuronic acid []. In addition, many Acer species exhibit different types of leaf color changes during growth and development, which play an important role in enriching the color of native forests []. Acer pseudosieboldianum is a genus of Acer in the family Aceraceae, which includes mostly deciduous trees or shrubs that are mainly distributed in eastern Heilongjiang, eastern Liaoning, and southeastern Jilin []. Its tree posture and leaf shape, and especially its red leaves in autumn, are of great ornamental value; therefore, it is an important landscape tree species. Research on Acer pseudosieboldianum has focused on resource evaluation, physiological characteristics, tissue culture, and environmental factors; however, few studies have been conducted on the mechanism of leaf coloration, which has seriously impeded the progress of research on molecular breeding for relevant leaf color []. In our previous study, we found a mutant with green and red leaves in spring and summer, respectively. Transcriptome sequencing revealed that the differential gene ANS is one of the key factors that affects variations in leaf color [].

Therefore, in the present study, we obtained the candidate ANS gene by screening the transcriptome database, analyzed the expression level of the ANS gene in variant and wild-type strains through real-time PCR (RT-PCR), analyzed its structural characteristics and physicochemical properties, and predicted its binding to miRNAs through bioinformatics analysis. The present study aimed to establish the molecular foundation for further understanding ApsANS gene regulation of leaf color and to provide a theoretical reference for leaf color formation mechanisms, expression regulation, and ornamental enhancement of Acer pseudosieboldianum.

2. Results

2.1. Screening and Expression Analysis of the ANS Gene in Acer pseudosieboldianum

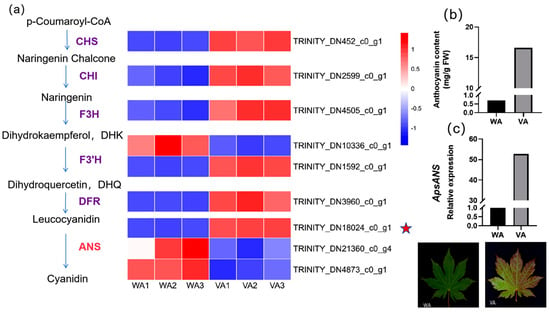

In this study, we screened the transcriptome to identify nine structural genes that were differentially expressed in the wild-type (WA) and variant (VA) leaves of Acer pseudosieboldianum during anthocyanin biosynthesis, and we plotted heatmaps based on their FPKM values, in which the expression of ANS, a key enzyme at the end of the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway, plays an important role in the coloration of Acer pseudosieboldianum leaves. Among the three ANS genes screened, only the ApsANS (TRINITY_DN18024_c0_g1) gene had very low expression in the green leaves (WA) and high expression in the red leaves (VA); the expression was consistent with leaf color (Figure 1a). Afterwards, the relative expression of the ApsANS gene in the leaves of wild-type and variant strains of Acer pseudosieboldianum was detected through real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR (Figure 1c), and the expression of the ApsANS gene was significantly lower in the wild strain than in the variegated strain. The anthocyanin content in the mature leaves of Acer pseudosieboldianum was determined spectrophotometrically, and the total anthocyanin content detected in the variegated strain was 16.63 mg/g, while the wild type of Acer pseudosieboldianum contained only a small amount of anthocyanin (0.7 mg/g), with the anthocyanin content of the variegated strain being about 23.76 times higher than that of the wild type (Figure 1b), and the trend of anthocyanin content was consistent with the trend of ApsANS gene expression, suggesting that the ApsANS gene may be a key gene for leaf pigmentation in Acer pseudosieboldianum.

Figure 1.

Determination of anthocyanin content and gene expression analysis. (a) Expression profiles of structural genes in wild-type Acer pseudosieboldianum and variants. The heatmap on the right is based on the RPKM values of the corresponding transcripts in the transcriptome database. (b) Comparison of anthocyanin content between wild type and variant of Acer pseudosieboldianum. ‘WA’ represents the wild-type strain, and ‘VA’ represents the variant strain. (c) Relative expression of ApsANS in wild type and variants.

2.2. Screening and Quantitative Analysis of Differential Metabolites

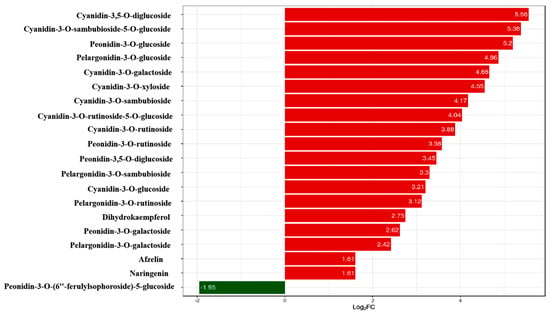

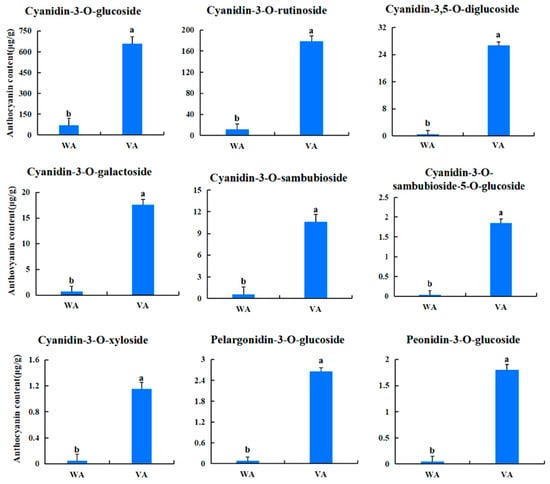

In order investigate the pigment composition affecting the coloration of Acer pseudosieboldianum leaves, we screened and quantified differential metabolites in wild-type and variant Acer pseudosieboldianum leaves through UPLC. We selected metabolites with a multiplicity of difference greater than 1.5 to plot a bar graph, as shown in Figure 2, which contained eight cyanidin types (cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside, cyanidin-3-O-sambubioside-5-O-glucoside, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, cyanidin-3-O-xyloside, cyanidin-3-O-sambubioside, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside-5-O-glucoside, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside), five peonidin types (peonidin-3-O-glucoside, peonidin-3-O-rutinoside, peonidin-3,5-O-diglucoside, peonidin-3-O-galactoside, peonidin-3-O-(6″-ferulylsophoroside)-5-glucoside), four pelargonidin types (pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-O-sambubioside, pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside, pelargonidin-3-O-galactoside) and three flavonoid metabolites (dihydrokaempferol, afzelin, naringenin). Among these, cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside showed the largest difference between the wild type and the variant. After that, we quantitatively analyzed the differential metabolites (Figure 3), and the results showed that the cyanidin metabolites were the highest in the leaves of Acer pseudosieboldianum, and the content of the wild type was significantly lower than that of the variant strain. In particular, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside was the highest in the leaves of Acer pseudosieboldianum, which indicated that it might be one of the important pigments affecting the coloration of the leaves of Acer pseudosieboldianum.

Figure 2.

Differential metabolites in wild type and variants. The horizontal coordinate is the log2FC of the differential metabolites; vertical coordinates are differentially expressed metabolites. The red color represents up-regulation of differentially expressed metabolites, and the green color represents down-regulation of differentially expressed metabolites.

Figure 3.

Content of each anthocyanoside metabolite in wild-type and variant Acer pseudosieboldianum. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

2.3. Cloning and Characterization of ApsANS cDNA

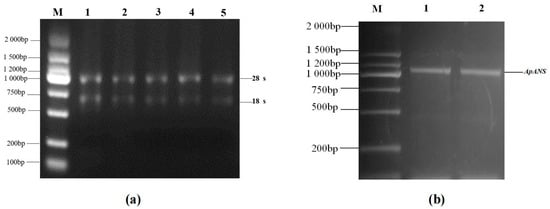

The RNA was extracted from Acer pseudosieboldianum leaves using the TIANGEN RNA Easy Fast Plant Tissue kit. The 28S, 18S, and 5S bands were clearly visible (Figure 4a), which were used for gene cloning. The TIANGEN Fast King cDNA First-Strand Synthesis kit was used for reverse transcription of the mRNA into cDNA. On the basis of the ApsANS fragment sequence obtained from the Acer pseudosieboldianum genomic data, a conserved fragment primer was designed for PCR amplification, and gel electrophoresis showed a clear bright band at approximately 1000 bp (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

cDNA amplification of the ApsANS gene in Acer pseudosieboldianum. (a) Lane 1–5: total RNA. (b) Lane 1–2: PCR product band based on Acer pseudosieboldianum cDNA template. (Lane M: DL2000 DNA marker).

2.4. Physicochemical Properties of the ApsANS Protein

The basic physicochemical properties of the ApsANS protein were analyzed through ExPASy. The results are shown in Table 1. The ApsANS gene has a full length of 1371 bp and a maximum open reading frame (ORF) of 1083 bp; it encodes a 360-amino-acid protein with a molecular weight of 40.684 kDa, a theoretical isoelectric point of 5.84, an instability coefficient of 49.75, an average hydrophilicity of −0.413, and a lipid coefficient of 89.58.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the ApsANS protein.

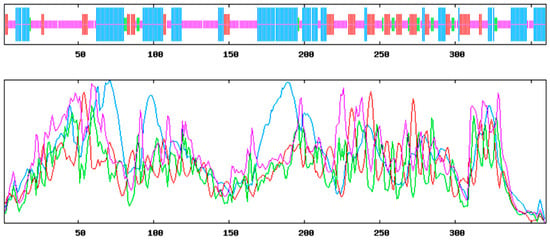

The prediction of the conserved structural domains of the ApsANS protein using the CD-search function on the NCBI website revealed that it contains the pcbC functional domain (Figure 5), with a conserved α-ketoglutarate and a divalent iron ion-dependent double oxygenase superfamily domain [2OG-Fe(II)_Oxy] at position 650–935 of the peptide chain. The results of secondary and tertiary structure prediction of the ApsANS protein showed that the structures mainly consisted of α-helix, irregular coils, and extended chains, which accounted for 35.56%, 17.50%, and 41.94% of the total structure, respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Prediction of conserved domain of the ApsANS protein.

Figure 6.

Secondary structure prediction of ApsANS. Alpha helix (blue); Random coil (purple); Extended strand (red); Beta turn (green).

2.5. Structural Analysis of the ApsANS Protein

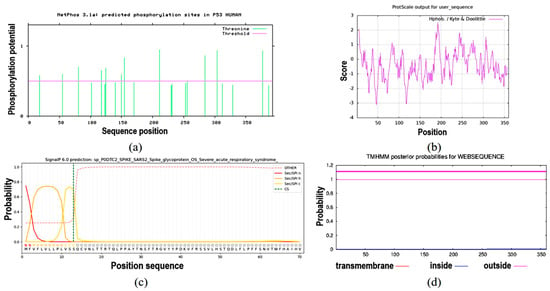

NetPhos 3.1 prediction analysis revealed that the protein contained 22 Thr phosphorylation sites (Figure 7a). The ProtScale online tool was used to predict the hydrophobic domain of the ApsANS protein from Acer pseudosieboldianum. The results showed that the ApsANS protein has one hydrophobic domain in the regions 20–36, 186–195, and 235–249 of its amino acid sequence (Figure 7b), which contains a mitochondrial targeting peptide, no chloroplast transport peptide, and a secretory pathway signaling peptide (Figure 7c). TMHMM predictions show that the protein does not have a transmembrane helix (Figure 7d). Subcellular localization prediction showed that the ApsANS protein was localized in the cytoplasm. The 3D structure of the ApsANS protein was further predicted using SWISS-MODEL. The ApsANS protein belongs to the α-ketoglutarate dioxygenase family, and the spatial structure is dominated by α-helix and random coiling; these findings are consistent with the predicted results of the secondary structure (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Prediction of hydrophobicity, transmembrane helix, signal peptide, and phosphorylation of the ApsANS protein. (a) Phosphorylation site prediction. (b) Prediction of hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity. (c) Signal peptides and their site prediction on proteins. (d) Prediction of transmembrane structural domains.

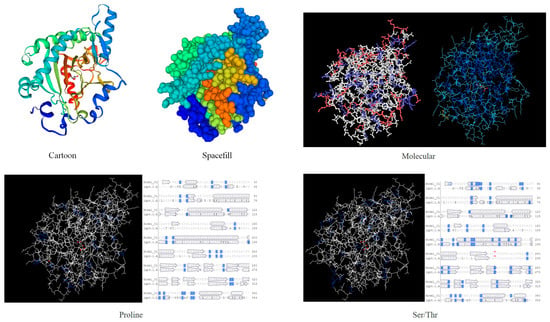

Figure 8.

3D structure prediction of the ApsANS protein.

2.6. miRNA Prediction of ApsANS in Acer pseudosieboldianum

The miRNA prediction of ApsANS was performed using the psRNATarget database (Table 2). The prediction results showed that the ApsANS gene might be regulated by miR6200, with the following sequence: UUUGGCCAACUAGAUCUAUGA.

Table 2.

ApsANS miRNA prediction.

2.7. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Evolutionary Tree Construction for the ApsANS Protein

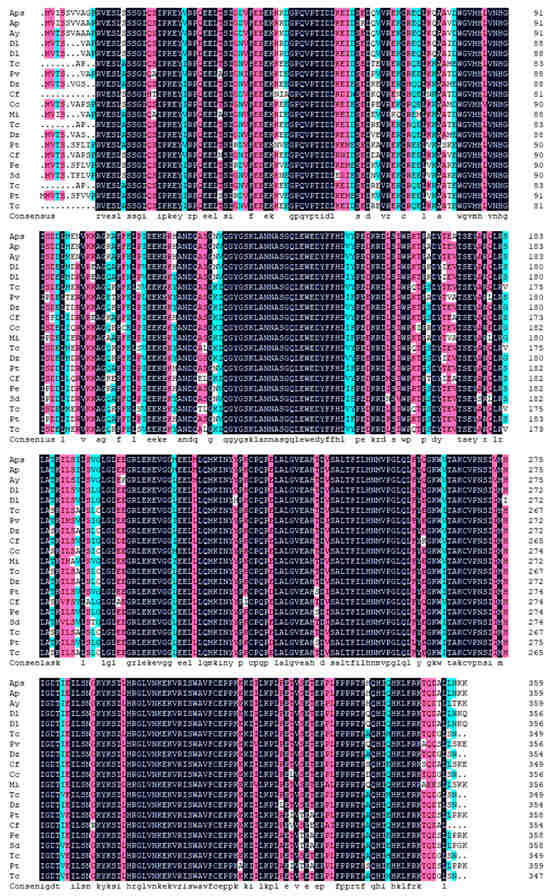

Multiple sequence comparison and phylogenetic tree construction of Acer pseudosieboldianum ApsANS with ANS protein sequences from other species are shown in Table A1. The amino acid sequences of species with high homology to the ApsANS protein were downloaded through the BLAST program in the NCBI database. Multiple comparisons of the homologous sequences were performed using DNAMAN software version 9.0, and the sequences of Acer palmatum (AWN08246.1), Dimocarpus longan (QRV61372.1), Dimocarpus longan (ACK76231.1), Pistacia vera (XM_031428804.1), and Mangifera indica (XM_044630098.1) were observed to be highly homologous to the ApsANS protein (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Multiple sequence alignment of the predicted amino acid sequence of ApsANS with other ANS proteins. (The species names corresponding to the abbreviated sections can be found in Abbreviations).

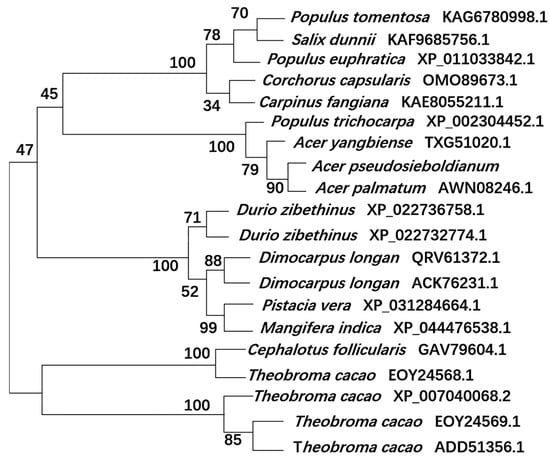

To further understand the evolutionary relationships between ApsANS and other plant ANS proteins, the NJ method using MEGA7.0 software was used to construct a phylogenetic tree, and all of the species were divided into four major taxa (Figure 10). The evolutionary relationship between ApsANS from Acer pseudosieboldianum, Acer palmatum, Acer yangbiense, and Populus trichocarpa, the family and genus rank of ApsANS, are distinguished from each other, and the evolution is basically in accordance with the plant’s taxonomic classification. Acer pseudosieboldianum and Ace palmatum share the closest evolutionary relationship. This may be because both Acer pseudosieboldianum and Ace palmatum are maple plants, and the ANS may have the same functions; hence, they share close evolutionary relationships. In general, the plant’s evolutionary relationships remained largely consistent with the results of the amino acid comparison.

Figure 10.

Evolutionary analysis of the ApsANS system.

3. Discussion

Anthocyanins and other flavonoids are the main pigments that determine the coloration of many plant tissues and organs []. Color changes in a variety of plants have been associated with anthocyanin biosynthesis, such as those reported for lichee (Litchi chinensis Sonn) [], mango (Mangifera indica Linn) [], strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) [], alfalfa (Medicago sativa) [], white clover (Trifolium repens) [], white primrose (Primula vulgaris) [], and other plants. Anthocyanin biosynthesis is one of the most deeply studied plant secondary metabolic pathways, and its synthesis is highly conserved []. In most plant species, anthocyanins are generated through a branch of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway with a group of catalytic enzymes [,]. Anthocyanin synthase (ANS) is a key enzyme gene expressed at the final step of the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway, which belongs to the dioxygenase gene family in the flavonoid pathway and relies on the α-ketoglutarate ion and the Fe2+ ion to catalyze the conversion of colorless anthocyanins into colored anthocyanins [,,], which plays an important role in regulating flower color, leaf color formation, and fruit coloration [,,].

In this study, we analyzed the expression pattern of the ApsANS gene in the mature leaves of Acer pseudosieboldianum wild-type and variant strains, and we found that the expression of the ApsANS gene was higher in the red variant leaf and lower in the green leaf, which was consistent with the transcriptome data and the anthocyanin content (Figure 1), suggesting that ApsANS may be related to the pigmentation of Acer pseudosieboldianum leaves. The UPLC results showed that the cyanidin metabolites may be the key substance influencing the final color formation of Acer pseudosieboldianum (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The ApsANS gene was successfully isolated from the leaves of Acer pseudosieboldianum through PCR (Figure 4). Analysis of the structural domains of the ApsANS protein revealed that the protein contains a pcbC functional domain and a conserved α-ketoglutarate and divalent iron ion-dependent dioxygenase superfamily region [2OG-Fe (II)_Oxy] at position 650–935 in the peptide chain (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The predicted secondary and tertiary structures of the ApsANS protein showed that the structures mainly included α-helix, irregular coils, and extended chains, which accounted for 35.56%, 17.50%, and 41.94% of the total structures, respectively (Figure 6). The ApsANS protein has a hydrophobic structural domain that contains a mitochondrial targeting peptide, no chloroplast transit peptide, and no secretory pathway signaling peptide, but the protein has no transmembrane structural domains. The 3D structure prediction revealed that the spatial structure of the ApsANS protein is dominated by α-helices and random coiling and that it belongs to the α-ketoglutarate dioxygenase family, and these findings are consistent with the predictions of the secondary structure (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Subcellular localization predicted that the ApsANS protein might be localized in the nucleus. BLAST comparison and phylogenetic tree construction showed that the ApsANS protein is relatively closely related to the ApANS protein (Figure 9 and Figure 10). miRNA molecules bind to the target miRNA through base pairing, which causes translation inhibition of the target miRNA after transcription, thus affecting the expression of protein [,]. In plants, miRNA can participate in gene expression during the synthesis of flavonoids, thus affecting the accumulation of flavonoids in leaves [,,]. The present study predicted that miR6200 may regulate the expression of the ApsANS gene and affect the synthesis of flavonoids (Table 2). Specific mechanisms of action need to be further investigated. In the next step, we will construct an overexpression vector for the ApsANS gene, and because the genetic transformation of Acer pseudosieboldianum is relatively difficult, we will choose to carry out stable transformation in Nicotiana benthamiana and analyze the role of MYB, bHLH, and WD40 regulatory factors on the ApsANS gene in order to further verify the function and clarify the molecular regulation mechanism of the ApsANS gene in the leaf color formation of Acer pseudosieboldianum. Our research findings are expected to provide a theoretical basis for future trait improvement of Acer pseudosieboldianum.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material, Strains, and Vectors

Acer pseudosieboldianum was used as the test material and grown in the nursery of Yanbian University in Jilin Province, China. Three-year old Acer pseudosieboldianum variant leaves were collected for ANS gene cloning. The red leaf variant was instantly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for gene cloning. Mature leaves of the variant (VA) and wild-type (WA) strains were also collected for leaf color expression analysis. The RNA extraction kit, high-fidelity enzymes and other reagents, and the reverse transcription kit were purchased from TIANGEN (Beijing, China). Escherichia coli DH5-α strains were obtained from TaKaRa (Dalian, China), and primer synthesis and sequencing were performed by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

4.2. Isolation of Total RNA and Synthesis of First-Strand cDNA

RNA was extracted from the leaves of Acer pseudosieboldianum using the RNA Easy Fast Plant Tissue kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), and the quality was checked using 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis. After its concentration was measured using a spectrophotometer and its integrity was validated through gel electrophoresis, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized through reverse transcription with the total RNA as the template in accordance with the instructions of the Fast King cDNA First-Strand Synthesis kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). The cDNA synthesized through reverse transcription was used as the template, and Primer 5.0 software was used to design specific primers as follows: ApsANS-F: ATGGTGATTTCATCGGTAGTAGCA; ApsANS-R: TTAGACTTTTTTGTTG AGGAGAGAGCA. The corresponding upstream and downstream primers were used for PCR amplification to clone ApsANS. The PCR was performed as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 32 cycles of amplification, each consisting of a denaturing step at 94 °C for 30 s, followed by annealing at 57 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 2 min. The last cycle was followed by a 5 min extension at 72 °C; subsequently, the PCR products were stored at 4 °C and examined through gel electrophoresis. The target gene fragments with the correct band size were recovered and purified using the agarose gel DNA recovery kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). In accordance with the instructions of the pMD19-T vector kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), the gel recovery product was ligated overnight with the pMD19-T vector. The ligation product was transformed into E. coli DH5α (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) receptor cells, after which the cells were shaken uniformly in LB solid medium containing ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C until white single colonies appeared on the medium. PCR amplification was performed to detect the presence or absence of target bands. The PCR reaction procedure was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, 32 cycles of amplification, each consisting of a denaturing step at 95 °C for 15 s, followed by annealing at 56 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 2 min. The last cycle was followed by a 5 min extension at 72 °C.

4.3. Determination of Anthocyanin Content

The anthocyanin extraction of Acer pseudosieboldianum followed the previous method, with some modifications [,]. We weighed 0.1 g of leaf samples in a 50 mL centrifuge tube, added 1% HCl–methanol solution to 20 mL, shook it gently and mixed it well, and then immersed it in 25 °C for 5–6 h, shaking every 2 h. The filtrate was filtered, and the supernatant was collected after centrifugation. The standard buffer was used as a blank control, and the absorbance values were detected at 530 nm and 600 nm with a ultraviolet spectrophotometer (INESA, Shanghai, China). Three biological replicates were performed, and the anthocyanin content was calculated as D530nm − D600nm = 0.01 (U).

4.4. Quantification of Anthocyanin Metabolites Through UPLC-ESI-MS/MS

Quantification of Anthocyanin Metabolites were detected by MetWare (Hubei, China) based on the AB Sciex QTRAP 6500 LC-MS/MS platform. The sample was freeze-dried, ground into powder (30 Hz, 1.5 min), and stored at −80 °C until needed. Then, 50 mg of powder was weighted and extracted with 0.5 mL of methanol/water/hydrochloric acid (500:500:1, v/v/v). Then, the extract was vortexed for 5 min, followed by ultrasound for 5 min, and then it was centrifuged at 12,000× g under 4 °C for 3 min. The residue was re-extracted by repeating the above steps again under the same conditions. The supernatants were collected and filtrated through a membrane filter (0.22 μm, Anpel, Shanghai, China) before LC-MS/MS analysis. The sample extracts were analyzed using an UPLC-ESI-MS/MS system (UPLC, ExionLC™ AD, SCIEX, The Netherlands; MS, Applied Biosystems 6500 Triple Quadrupole, SCIEX, The Netherlands). The analytical conditions were as follows. UPLC: column, WatersACQUITY BEH C18 (1.7 µm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm); solvent system, water (0.1% formic acid):methanol (0.1% formic acid); gradient program, 95:5 v/v at 0min, 50:50 v/v at 6 min, 5:95 v/v at 12 min, hold for 2 min, 95:5 v/v at 14 min; hold for 2 min; flow rate, 0.35 mL/min; temperature, 40 °C; injection volume, 2 µL. Quantification of metabolites was performed using scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) through mass spectrometry.

4.5. Screening and Expression Analysis of ANS Genes

Heat mapping of related structural genes was conducted using the Hiplot online tool (https://hiplot.com.cn/cloud-tool, accessed on 27 November 2024). To verify the correctness of the expression pattern of the candidate genes, qRT-PCR was performed to validate the ApsANS gene, which is associated with anthocyanin synthesis. cDNAs from wild-type and variant leaves of Acer pseudosieboldianum were used as templates for quantitative analysis using a fluorescence quantification kit (SYBR® Premix Ex Taq, TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and a Gene9600 real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument (BIOER, Hangzhou, China) with the following primer sequences: ApsANS-F: GAAAAGGAAGTAGGTGGTATGG; ApsANS-R: CAATGGTGTCTCCGATGTGC. The reaction procedure was 95 °C for 3 min, 95 °C for 10 s, annealing temperature of 58 °C for 30 s, and 39 cycles; finally, the lysis curve program was added. The relative gene expression of each sample was calculated using the 2−△△Ct method [].

4.6. Analysis of Physicochemical Properties of the ApsANS Protein

The ProtParam tool in the ExPASY server (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 22 March 2022) was used to predict the molecular weight, isoelectric point, instability coefficient, lipid coefficient, and hydrophobicity of ApsANS []. Online software SOPMA 2.0 (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?Page=npsa_sopma.html, accessed on 24 March 2022) was used to predict the secondary structure of the protein.

4.7. Conservative Domain of the ApsANS Protein and miRNA Prediction

By using MEME program V5.3.2 (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme, accessed on 23 March 2022), the structure of the ApsANS protein was predicted under the assumption that it is a conserved sequence, with the following parameters: number of repetitions, nonspecific; width of the motif, 6–50; number of motifs, 6; other parameters, default values. All motifs recognized by the MEME program were searched using the InterProScan program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/search/sequence/, accessed on 23 March 2022) in the InterPro database []. The online tool psRNATarget (https://www.zhaolab.org/psRNATarget/, accessed on 7 April 2022) was used for target prediction of miRNA [].

4.8. Sequence Alignment Analysis and Construction of Phylogenetic Tree

Mega7.0 software was used to construct the system evolution tree and for sequence analysis. The amino acid sequences of the ApsANS protein of Acer pseudosieboldianum were compared and analyzed. The comparison results were used to construct the phylogenetic tree through the neighbor joining (NJ) method, with 1000 bootstrap replicates and default values for other parameters [].

5. Conclusions

In this study, the expression pattern, structural characteristics, and physicochemical properties of the anthocyanin synthase gene ApsANS in Acer pseudosieboldianum were analyzed. Gene expression analysis showed that the expression of the ApsANS gene in the variant was significantly higher than in the wild type, and the trend was consistent with the anthocyanin content. The cyanidin metabolites may be key substances in the formation of Acer pseudosieboldianum colors. The ApsANS gene belongs to the α-ketoglutarate dioxygenase family, and it has a pcbC functional domain, which may be regulated by miR6200 to affect flavonoid synthesis. This study further explored the expression pattern of the ApsANS gene in Acer pseudosieboldianum and provided some theoretical basis for breeding Acer pseudosieboldianum varieties rich in anthocyanins.

Author Contributions

Software, M.L. and J.Y.; methodology, Z.G. and X.L.; validation, M.L. and Z.W.; formal analysis, M.L. and Z.W.; data curation, M.L. and Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.; writing—review and editing, M.L. and L.R.; supervision, L.R and Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32060692), the Science and Technology Development Plan Project of Jilin Province (20250104322JC), the Science Foundation of Science and Technology of the Education Department of Jilin Province (JJKH20250420KJ), the Yanbian University Doctoral Initiation Fund (ydbq202407), and the Yanbian University School Enterprise Cooperation Project (ydxq202402).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The sequenced raw reads generated in this study have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), with BioProject ID PRJNA805289.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Aps | Acer pseudosieboldianum |

| Ap | Acer palmatum |

| Ay | Acer yangbiense |

| Dl | Dimocarpus longan |

| Tc | Theobroma cacao |

| Pv | Pistacia vera |

| Dz | Durio zibethinus |

| Cf | Cephalotus follicularis |

| Cc | Corchorus capsularis |

| Mi | Mangifera indica |

| Pt | Populus tomentosa |

| Cf | Carpinus fangiana |

| Pe | Populus euphratica |

| Sd | Salix dunnii |

| Pt | Populus trichocarpa |

Appendix A

Table A1.

The ANS protein sequence for constructing the phylogenetic tree.

Table A1.

The ANS protein sequence for constructing the phylogenetic tree.

| Species Names | GenBank ID |

|---|---|

| Acer palmatum | AWN08246.1 |

| Acer yangbiense | TXG51020.1 |

| Dimocarpus longan | QRV61372.1 |

| Dimocarpus longan | ACK76231.1 |

| Theobroma cacao | XP_007040068.2 |

| Pistacia vera | XP_031284664.1 |

| Durio zibethinus | XP_022736758.1 |

| Cephalotus follicularis | GAV79604.1 |

| Corchorus capsularis | OMO89673.1 |

| Mangifera indica | XP_044476538.1 |

| Theobroma cacao | EOY24569.1 |

| Durio zibethinus | XP_022732774.1 |

| Populus tomentosa | KAG6780998.1 |

| Carpinus fangiana | KAE8055211.1 |

| Populus euphratica | XP_011033842.1 |

| Salix dunnii | KAF9685756.1 |

| Theobroma cacao | ADD51356.1 |

| Populus trichocarpa | XP_002304452.1 |

| Theobroma cacao | EOY24568.1 |

References

- Li, H.; Liu, J.; Pei, T.; Bai, Z.; Han, R.; Liang, Z. Overexpression of SmANS Enhances Anthocyanin Accumulation and Alters Phenolic Acids Content in Salvia miltiorrhiza and Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge f. alba Plantlets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Tang, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, Y. A MYB/bHLH complex regulates tissue-specific anthocyanin biosynthesis in the inner pericarp of red-centered kiwifruit Actinidia chinensis cv. Hongyang. Plant J. 2019, 99, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberto, S.; Silva, S.; Meireles, M.; Faria, A.; Pintado, M.; Calhau, C. Blueberry anthocyanins in health promotion: A metabolic overview. J. Funct. Foods. 2013, 5, 1518–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Du, X.; Cui, D.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, G. Improvement of stability of blueberry anthocyanins by carboxymethyl starch/xanthan gum combinations microencapsulation. Food Hydrocolloid. 2019, 91, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, D.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. SmBICs Inhibit Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, M.; Wen, C.; Xie, X.; Liu, L. Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis of the anthocyanin regulatory networks in Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge. flowers. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuraini, L.; Tatsuzawa, F.; Ochiai, M.; Suzuki, K.; Nakatsuka, T. Two Independent Spontaneous Mutations Related to Anthocyanin-less Flower Coloration in Matthiola incana Cultivars. Hortic. J. 2021, 90, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Han, M.; Liu, Q.; Yang, C.; Li, H. Pigment profile and gene analysis revealed the reasons of petal color difference of crabapples. Braz. J. Bot. 2021, 44, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellaporta, S.L.; Greenblatt, I.; Kermicle, J.L.; Hicks, J.B.; Wessler, S.R. Molecular cloning of the maize R-nj allele by transposon tagging with Ac. In Chromosome Structure and Function; Impact New Concepts; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 263–282. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmouth, R.C.; Turnbull, J.J.; Welford, R.W.; Clifton, I.J.; Prescott, A.G.; Schofield, C.J. Structure and mechanism of anthocyanidin synthase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Structure 2002, 10, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.R.; Hong, S.T.; Yoo, Y.-K.; An, G.; Kim, S.-R. Molecular cloning and analysis of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes preferentially expressed in apple skin. Plant Sci. 2003, 165, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Pan, Q.; Zhan, J.; Huang, W. Gene transcript accumulation, tissue and subcellular localization of anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) in developing grape berries. Plant Sci. 2010, 179, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.Z.; Hu, F.C.; Hu, G.B.; Li, X.J.; Huang, X.M.; Wang, H.C. Differential expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in relation to anthocyanin accumulation in the pericarp of Litchi chinensis Sonn. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Gao, A.; Huang, J. Cloning and expression of anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) gene from peel of mango (Mangifera indica Linn). Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 8, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.F.; Chen, Z.D.; Sun, W.J.; Lin, F.M.; Xue, Z.H.; Huang, Y.; Tang, X.H. Cloning and bioinformatics analysis of tea tree CsANS gene and its promoter. Tea Sci. 2016, 36, 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Sui, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H. Transcriptome-Wide Analysis Reveals Key DEGs in Flower Color Regulation of Hosta plantaginea (Lam.) Aschers. Genes 2020, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhu, D.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Zeng, H. Metabonomic Profiling Analyses Reveal ANS Upregulation to Enhance the Flavonoid Pathway of Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato Storage Root in Response to Deep Shading. Agronomy 2021, 11, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Suo, H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, L.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the ANS Gene Family in Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Horticulturae. 2023, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, B.; Yu, Y.; Liu, T.; Song, B. Functional analysis of an anthocyanin synthase gene StANS in potato. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.T.; Chen, Y.L.; Zhang, X.H.; Cai, M.L.; Yu, Z.C.; Peng, C.L. ANS-deficient Arabidopsis is sensitive to high light due to impaired anthocyanin photoprotection. Funct. Plant Biol. 2019, 46, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattus-Araya, E.; Guajardo, J.; Herrera, R.; Moya-Leon, M.A. ABA Speeds Up the Progress of Color in Developing F. chiloensis Fruit through the Activation of PAL, CHS and ANS, Key Genes of the Phenylpropanoid/Flavonoid and Anthocyanin Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Sun, X.; Fang, B.; Sheng, X.; Yuan, D. The Cds.71 on TMS5 May Act as a Mutation Hotspot to Originate a TGMS Trait in Indica Rice Cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wei, Y.; Liang, C.; Guo, J.; Niu, T.; Zhang, P.; Wen, P. VvANR silencing promotes expression of VvANS and accumulation of anthocyanin in grape berries. Protoplasma 2022, 259, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, T.; Li, P.; Li, L.; Zhang, Q. Research advances in and prospects of ornamental plant genomics. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.L.; Huang, H.; Fu, J.X.; Hong, Y. Advances in molecular breeding of ornamental plants. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2013, 48, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Chen, Z.; Tang, F.; Xuan, Y.; Yang, F.; Lu, X.Y.; Fu, S.L. Study on leaf color related chemicals components based on comparing. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 2019, 46, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.K.; Fang, J.B.; Qi, X.J.; Lin, M.M.; Zhong, Y.P.; Sun, L.M.; Cui, W. Combined analysis of the fruit metabolome and transcriptome reveals candidate genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis in Actinidia arguta. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Muhammad, W.H.; Tao, L.; Zhang, R.; Yun, Q.; Peter, H.; Zhiling, D.; Luo, G.; Guo, H.; Ma, Y. De novo genome assembly of the endangered Acer yangbiense, a plant species with extremely small populations endemic to Yunnan Province, China. GigaScience 2019, 8, giz085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, J.J. Evidence of Constrained Divergence and Conservatism in Climatic Niches of the Temperate Maples (Acer L.). Forests 2021, 12, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderen, D.; Jong, P.; Oterdoom, H.J. Maples of the World; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Sun, T.; Li, S.; Wen, J.; Zhu, L.; Yin, T.; Yan, K.; Xu, X.; Li, S.; Mao, J.; et al. The Acer truncatum genome provides insights into nervonic acid biosynthesis. Plant J. 2020, 104, 662–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quambusch, M.; Bucker, C.; Haag, V.; Meier-Dinkel, A.; Liesebach, H. Growth performance and wood structure of wavy grain sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.) in a progeny trial. Ann. For. Sci. 2021, 78, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, D.Z.; Tian, B. Diversity in seed oil content and fatty acid composition in Acer species with potential as sources of nervonic acid. Plant Divers. 2021, 43, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, H.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X. Transcriptomics profiling of Acer pseudosieboldianum molecular mechanism against freezing stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.F.; Zhao, D.H.; Zhang, J.Q.; Chen, J.S.; Li, J.L.; Weng, Z.; Rong, L.P. De novo transcriptome sequencing and anthocyanin metabolite analysis reveals leaf color of Acer pseudosieboldianum in autumn. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Cai, K.; Han, Z.; Zhang, S.; Sun, A.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, X. Chromosome-level genome assembly for Acer pseudosieboldianum and highlights to mechanisms for leaf color and shape change. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 850054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Weng, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, B.; Gao, Y.; Rong, L. De novo transcriptome revealed genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis, transport, and regulation in a mutant of Acer pseudosieboldianum. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, H.F.; Wu, X.; Xian, C.; Lei, J. Study on cyanidin metabolism in petals of pink-flowered strawberry based on transcriptome sequencing and metabolite analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.R.; Wang, L.R.; Cui, G.X.; Zhou, X.H.; Duan, X.R.; Yang, H.S. Identification of the regulatory networks and hub genes controlling alfalfa floral pigmentation variation using RNA-sequencing analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 1205–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.S.; Tian, H.; Chen, M.X.; Xiong, J.B.; Cai, H.; Liu, Y. Transcriptome analysis reveals potential genes involved in flower pigmentation in a red-flowered mutant of white clover (Trifolium repens L.). Genomics 2018, 110, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhai, Y.H.; Luo, X.N.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Q.Q. Comparative transcriptome analyses reveal genes related to pigmentation in the petals of red and white Primula vulgaris cultivars. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2019, 25, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lu, N.; Liu, C.; Dixon, R.A.; Wu, Q.; Mao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; He, L.; Zhao, B.; et al. Mtgstf7, a tt19-like gst gene, is essential for accumulation of anthocyanins, but not proanthocyanins in medicago truncatula. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 4129–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koes, R.; Verweij, W.; Quattrocchio, F. Flavonoids: A colorful model for the regulation and evolution of biochemical pathways. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hichri, I.; Barrieu, F.; Bogs, J.; Kappel, C.; Delrot, S.; Lauvergeat, V. Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2465–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Gong, Z.; Tanaka, Y.; Yamazaki, M. Direct evidence for anthocyanidin synthase as a 2-oxoglutaratedependent oxygenase: Molecular cloning and functional expression of cDNA from a red forma of Perilla frutescens. Plant J. 1999, 17, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Duan, N.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, H. Spray treatment of leaves with Fe2+ promotes procyanidin biosynthesis by upregulating the expression of the F3H and ANS genes in red rice grains (Oryza sativa L.). J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 100, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, K.; Yang, D.; Liu, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, P. Roles of the 2-Oxoglutarate-Dependent Dioxygenase Superfamily in the Flavonoid Pathway: A Review of the Functional Diversity of F3H, FNS I, FLS, and LDOX/ANS. Molecules 2021, 26, 6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Song, L.; Yang, Z.; Qiu, M.; Wang, J.; Shi, S. Anthocyanins: Promising Natural Products with Diverse Pharmacological Activities. Molecules 2021, 26, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Meng, Z.; Ji, W.; Wang, C. Transcriptomic and Lipidomic Analysis of Lipids in Forsythia suspensa. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 758362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunil, L.; Shetty, N.P. Biosynthesis and regulation of anthocyanin pathway genes. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2022, 106, 1783–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirumalai, V.; Swetha, C.; Nair, A.; Pandit, A.; Shivaprasad, P.V. miR828 and miR858 regulate VvMYB114 to promote anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation in grapes. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 4775–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.F.; Zhou, Y.J.; Chen, Z.S.; Zeng, J.; Huang, H.; Jiang, Y.M.; Zhu, H. Involvement of miRNA-mediated anthocyanin and energy metabolism in the storability of litchi fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 165, 111200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, C.; Mu, G. Multi-Omics and miRNA Interaction Joint Analysis Highlight New Insights Into Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, M.; Rodrigues, J.; Badim, H.; Geros, H.; Conde, A. Exogenous Application of Non-mature miRNA-Encoded miPEP164c Inhibits Proanthocyanidin Synthesis and Stimulates Anthocyanin Accumulation in Grape Berry Cells. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 700679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Ma, H.; Duan, X.; Gao, S.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, Y. The R2R3-MYB gene PsMYB58 positively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in tree peony flowers. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 164, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabino, I.; Mancinelli, A.L. Light, temperature, and anthocyanin production. Plant Physiol. 1986, 81, 922–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Chen, M.; He, N.; Chen, X.; Wang, N.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, T.; Xu, H.; Fang, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. MdGSTF6, activated by MdMYB1, plays an essential role in anthocyanin accumulation in apple. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative pcr and the 2(T)(-delta delta c) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Humana: Louisville, KY, USA, 2005; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37 (Suppl. S2), W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Fan, J.; Lu, C.; Ren, J.; Qi, F.; Huang, H.; Dai, S. ScGST3 and multiple R2R3-MYB transcription factors function in anthocyanin accumulation in Senecio cruentus. Plant Sci. 2021, 313, 111094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).