Wolves, Crows, Spiders, and People: A Qualitative Study Yielding a Three-Layer Framework for Understanding Human–Wildlife Relations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Extant Synopses of the Human Dimensions in Wildlife Conservation and Management

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Interview Procedure

2.3. Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

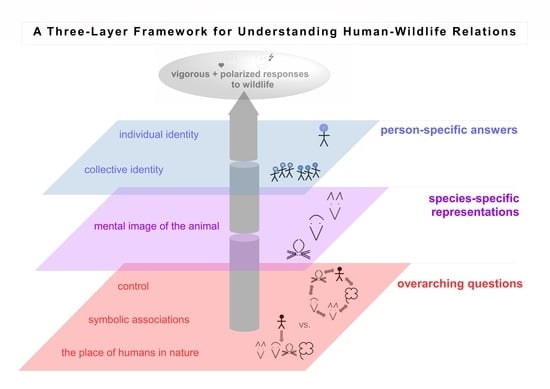

3.1. Person-Specific Factors

3.2. Species-Specific Factors

3.2.1. Wolves

3.2.2. Corvids

3.2.3. Spiders

3.2.4. An Overlap of Species-Specific Mental Images

3.3. Overarching Factors

3.3.1. The Question of Humans’ Place in Nature

3.3.2. The Question of Control

3.3.3. Further Questions and the Interlocking of Layers: Future Research

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Three Layers | Factors Found to Impact Human–Wildlife Relations in This Study | König et al., 2020 [26] | Manfredo and Dayer, 2004 [27] | Dickmann, 2010 [20] | Bathia et al., 2020: 5 Ultimate Factors [17] | Kansky and Knight, 2014 [19] | Kansky, Kidd and Knight, 2016: Wildlife Tolerance Model [28] | Pertinent Concepts in the Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-specific factors - individual identity | micro-level | Sociodemographic variables | ||||||

| personal affectedness and acuteness of being affected | micro-level | perception of risk: actual and perceived costs | perception of risk | tangible and intangible costs tangible and intangible benefits | tangible and intangible costs tangible and intangible benefits | |||

| social risk factor: vulnerability and wealth environmental risk factor: land use management | resource dependence, e.g., wealth, occupation, education | land use and dependence, e.g., wealth | ||||||

| context adaptation on the local level | social risk factor | exposure and experience | exposure and positive/negative meaningful experiences with species | closeness to established wildlife populations [12] | ||||

| Interpretation patterns [29] life themes and visions originating in a person’s biography personality traits | micro-level: behavior | social risk factor | personal habit | |||||

| micro-level: norms and attitudes | social risk factor: beliefs and values | attitudes towards species | general values personal and social norms | sociocultural value concept [81] | ||||

| micro-level: cognition and affect | salience of animal knowledge | interest in animals empathy | ||||||

| person-specific factors - collective identity | ascriptions to the opposing party:

| social risk factor: distrust and animosity | social interactions | cohort and demographic group | membership in stakeholder group | |||

| macro-level: cultural character | social risk factors: religious beliefs | religion animism [128] | ||||||

| Species-specific factors | capacity building and damage prevention on the regional and local levels | level of wildlife damage environmental risk factor: behavior and management of species; physical features of environment | nature of interaction with the animal, e.g., frequency and magnitude of conflict | (perceived) species characteristics, e.g., abundance and population density mitigation measures | a species’ ecology | |||

| mental image of the animal: perceived features of, as well as beliefs and stereotypes about a specific animal species that are shared between participants (features including, but transcending the species’ ecology) | micro-level: affect and cognition | taxonomic bias anthropomorphism | factors shaping species preference [97,98] stereotype content model [129] Big Bad Wolf stereotype [4] Anthropomorphism [130,131] mind perception [132] species’ belonging to a landscape [6,81,82] | |||||

| micro-level: affect | affective dimension of risk perception | intangible costs: psychological costs of danger or risk intangible benefits: positive emotions | intangible costs: negative emotions, fear, danger, nuisance and stress intangible benefits: positive emotions positive and negative meaningful events | affect for the species [133] species-specific patterns of fear [115,134,135,136] | ||||

| Overarching, fundamental questions raised by all human–wildlife interactions | A competition for resources exists between humans and wildlife—how should it be resolved? What is a “fair” balance between humans’ and animals’ needs? | governance and legal frameworks on international to regional to local level | macro-level | social risk factors: human–human conflicts; inequality and power | perception of risk: media, and law and policy | legal status of land landscape characteristics property characteristics | trust in institutions | political geographies politicization of conflict [137] urban–rural divide NIMBY-effect [138] |

| The place of humans in nature: Are humans… -… the centerpiece of the world (anthropocentrism) or a curse for the remainder of creation (anti-anthropocentrism) or individual beings amongst individual beings (biocentrism) or one species in a web of species (ecocentrism)? -… connected with nature or distinct from nature? - … endowed with a responsibility to care for their fellow animals or endowed with the right to manage nature? Are wild animals to be viewed as - collections of individuals or - as the whole of a species? | macro level: Wildlife value orientations “mutualism and domination“ | value orientations | wildlife value orientations | Kellert’s [121] ten types of value orientations and two fundamental dimensions “utility“ and “affect“ anthropocentrism vs. biocentrism vs. ecocentrism, and pluralism [102,107] biophilia [90,139] value basis for environmental concern [103] new environmental paradigm [104] separation vs. coexistence model in conservation [109] perspectives of hyper-separation vs. collaboration [140] dualistic vs. biocultural view of wilderness [141] | ||||

| Control: Dealing with wildlife agency: - allowing free reign or - restricting wildlife behavior? Reacting to acute affectedness: - helplessness and/or - reactive aggression? | micro-level: perceptions of control | self-efficacy behavioral control | control one’s own response [115] desirability of control [119] locus of control [142] control in terror management Theory [143] autonomy of nature [118] | |||||

| symbolic meaning associated to wild animals e.g., associations to “darkness” (evil, mortality); expressed through a prototypical dark exterior | symbolism | landscape as symbolic environment [100] deeper levels of conflict [101] terror management theory [144,145] |

| Code | Collective Identity—Stakeholder Group | Nationality | Gender | Age | Degree and Manner of Being Affected | Attitude to Model Wildlife | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | O | Animals owned | P | L | E | A | S | |||||||

| W1 | L | A | S | G | M | 59 | no wolf area, urban resident | positive | ||||||

| W2 | H | G | M | 73 | lives in area of dispersing wolves | ambivalent | ||||||||

| W3 | H | G | M | 70 | lives in area of dispersing wolves | ambivalent | ||||||||

| W4 | H | G | M | 73 | lives in area of dispersing wolves | negative | ||||||||

| W5 | H | G | M | 70 | lives in area of dispersing wolves | neutral | ||||||||

| W6 | O | Horses | E | G | M | 83 | lives in wolf area; unconfirmed wolf attack on horses | negative | ||||||

| W7 | H | P | L | G | M | 50+ | lives in wolf area; lobbies for affected farmers | ambivalent | ||||||

| C1 | E | S | CH | F | 33 | no corvid populations nearby | neutral | |||||||

| C2 | H | G | M | 43 | lives close to rookery | positive | ||||||||

| C3 | H | L | G | M | 47 | avid hunter of crows | positive | |||||||

| C4 | O | Sheep | E | G | F | 60 | alleged attack on lambs | ambivalent | ||||||

| C5 | A | G | F | 59 | lives close to rookery | positive | ||||||||

| C6 | G | M + F | 70 | live close to rookery | negative | |||||||||

| S1 | A | G | M | 27 | phobic | negative | ||||||||

| S2 | A | G | F | 33 | normal level of affectedness | neutral | ||||||||

| S3 | Pet spiders | G | M | 27 | owns tarantulas | positive | ||||||||

| S4 | G | F | 29 | phobic | negative | |||||||||

| S5 | Pet spiders | G | M | 30 | owns tarantulas | positive | ||||||||

| S6 | A | G | M | 30 | previously phobic | ambivalent | ||||||||

| S7 | Pet spiders | S | G | M | 36 | researches spiders | positive | |||||||

| total | 7 | 2 | - | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 19 G 1 CH | 14 M 5 F 1 Couple | Md: 47 Mn: 50 | - | - | |

Appendix B

- Have you had any personal experiences with wolves/crows/spiders?

- Which feelings arise when you think about wolves/crows/spiders?

- What is it about wolves/crows/spiders that evokes these thoughts and feelings?

- (Arrangement of figures:) How would you describe your personal relation to wolves/crows/spiders? Can you illustrate your relation to wolves/crows/spiders with these figures?

- Could wolves/crows/spiders stand as symbols for something? If so, for what?

- Other people might see wolves/crows/spiders in a different light. What distinguishes you from these people? Why do you like/dislike wolves/crows/spiders while others dislike/like them?

- (Arrangement of figures:) How do you think would these people that like/dislike wolves/crows/spiders arrange these figures to depict their view of wolves/crows/spiders?

- There are many different opinions about whether humans should restrict their freedom in order to be considerate of wildlife. What do you think?

- What enrages you about other people’s behavior towards wolves/crows/spiders?

- How would you explain to a child what is key in human-wolf/crow/spider relations?

- If you were granted three wishes with regard to wolves/crows/spiders—what would they be?

- Imagine you were a god/goddess who could arrange the world in any possible way. You could change and create everything: Humans, animals, landscapes—just everything. How would you arrange the world in a way that human–wildlife conflicts are eliminated?

- Ideally, what ought to be the role of humans in nature?

- What constitutes the biggest challenge in human coexistence with wolves/crows/spiders?

- What is the biggest possibility inherent in human coexistence with wolves/crows/spiders?

- If you had the power to decide: What would be a realistic solution to the conflict between humans and wolves/crows/spiders?

References

- Treves, A.; Karanth, K.U. Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, U.M.; Hackett, P.M. Wolves, Crows, and Spiders: An eclectic Literature Review inspires a Model explaining Humans’ similar Reactions to ecologically different Wildlife. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, W. Ökologie der Wirbeltiere: Vögel und Säugetiere; UTB: Bayern, Germany, 2017; Volume 8675. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens, U.M.; Hackett, P.M. The Big Bad Wolf: The Formation of a Stereotype. Ecopsychology 2017, 9, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lescureux, N.; Linnell, J.D.C. Knowledge and Perceptions of Macedonian Hunters and Herders: The Influence of Species Specific Ecology of Bears, Wolves, and Lynx. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, S.; Skogen, K.; Krishnan, S. Locating Human-Wildlife Interactions: Landscape Constructions and Responses to Large Carnivore Conservation in India and Norway. Conserv. Soc. 2015, 13, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Latour, B. Das Parlament der Dinge, 2nd ed.; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Margulies, J.D.; Karanth, K.K. The production of human-wildlife conflict: A political animal geography of encounter. Geoforum 2018, 95, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, A.; Rikoon, S. Political Ecology Revisited: Integration of Politics and Ecology Does Matter. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, S.; Barua, M.; Beinart, W.; Dickman, A.; Holmes, G.; Lorimer, J.; Loveridge, A.; Macdonald, D.; Marvin, G.; Redpath, S.; et al. An interdisciplinary review of current and future approaches to improving human-predator relations. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 31, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schröder, V.; Steiner, C. Pragmatist Animal Geographies: Mensch-Wolf-Transaktionen in der schweizerischen Calanda-Region. Geographische Zeitschrift 2020, 108, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressel, S.; Sandström, C.; Ericsson, G. A meta-analysis of studies on attitudes toward bears and wolves across Europe 1976–2012. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 29, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.C.; Lambert, J.E.; Lawhon, L.A.; Salerno, J.; Hartter, J. Wolves are back: Sociopolitical identity and opinions on management of Canis lupus. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C.; Wagner, A.; Rögele, A.; Hummel, E.; Tomažič, I. Attitudes toward and Knowledge about Wolves in SW German Secondary School Pupils from within and outside an Area Occupied by Wolves (Canis lupus). Animals 2020, 10, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van Eeden, L.M.; Rabotyagov, S.S.; Kather, M.; Bogezi, C.; Wirsing, A.J.; Marzluff, J. Political affiliation predicts public attitudes toward gray wolf (Canis lupus) conservation and management. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.K.; Ericsson, G.; Heberlein, T.A. A quantitative summary of attitudes toward wolves and their reintroduction. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2002, 30, 575–584. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, S.; Redpath, S.M.; Suryawanshi, K.; Mishra, C. Beyond conflict: Exploring the spectrum of human–wildlife interactions and their underlying mechanisms. Oryx 2019, 54, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, P.M. Conservation and the Consumer: Understanding Environmental Concern; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kansky, R.; Knight, A.T. Key factors driving attitudes towards large mammals in conflict with humans. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 179, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dickman, A.J. Complexities of conflict: The importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human-wildlife conflict. Anim. Conserv. 2010, 13, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinko, M.; Ertl, T.; Aal, K.; Wulf, V. Transitions by Methodology in Human-Wildlife Conflict-Reflections on Tech-based Reorganization of Social Practices. In Proceedings of the LIMITS’ 21: Workshop on Computing within Limits, Siegen, Germany, 14–15 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, R.; Dhee; Patil, O.; Surve, N.; Andheria, A.; Linnell, J.D.C.; Athreya, V. Sharing spaces and entanglements with big cats: The warli and their Waghoba in Maharashtra, India. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, G. The Wolf, the Saami and the Urban Shaman. In Natural Enemies—People-Wildlife Conflicts in Anthropological Perspective; Knight, J., Ed.; Routlege: London, UK, 2000; pp. 170–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pates, R.; Leser, J. The Wolves are Coming Back: The Politics of Fear in Eastern Germany; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siemer, W.F.; Jonker, S.A.; Decker, D.J.; Organ, J.F. Toward an understanding of beaver management as human and beaver densities increase. Hum. Wildl. Interact. 2013, 7, 114–131. [Google Scholar]

- König, H.J.; Kiffner, C.; Kramer-Schadt, S.; Fürst, C.; Keuling, O.; Ford, A.T. Human-Wildlife Coexistence in a Changing World. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredo, M.J.; Dayer, A.A. Concepts for exploring the social aspects of human–wildlife conflict in a global context. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2004, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansky, R.; Kidd, M.; Knight, A.T. A wildlife tolerance model and case study for understanding human wildlife conflicts. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 201, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bjerke, T.; Kaltenborn, B.P. The relationship of ecocentric and anthropocentric motives to attitudes toward large carnivores. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lute, M.L.; Carter, N.H.; López-Bao, J.V.; Linnell, J.D. Conservation professionals agree on challenges to coexisting with large carnivores but not on solutions. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 218, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondini, M.; Hunziker, M. Psychological Factors Influencing Human Attitudes towards Brown Bears: A Case Study in the Swiss Alps. Umweltpsychologie 2018, 22, 8–29. [Google Scholar]

- Skogen, K. Who’s Afraid of the Big, Bad Wolf? Young People’s Responses to the Conflicts Over Large Carnivores in Eastern Norway. Rural. Sociol. 2001, 66, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagle, K.M.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Wilson, R.S. The role of affect in public support and opposition to wolf management. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2012, 17, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oevermann, U. Zur Analyse der Struktur von sozialen Deutungsmustern. Sozialer Sinn 2001, 2, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomssen, W. Deutungsmuster-eine Kategorie der Analyse von Gesellschaftlichem Bewußtsein. In Gesellschaftliche Voraussetzungen der Erwachsenenbildung; Tietgens, H., Ed.; Studienbibliothek für Erwachsenenbildung: Frankfurt, Germany, 1991; Volume 1, pp. 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Soeffner, H.-G. Interaktion und Interpretation—Überlegungen zu den Prämissen des Interpretierens in Sozial- und Literaturwissenschaft. In Interpretative Verfahren der Sozial—Und Textwissenschaften; Soeffner, H.-G., Ed.; J.B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung: Stuttgart, Germany, 1979; pp. 328–351. [Google Scholar]

- Lamnek, S. Qualitative Sozialforschung; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, F. Biographieforschung und narratives Interview. Sozialwissenschaftliche Prozessanalyse. Grundl. Der Qual. Soz. 2016, 55–73. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvdf09cn (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Low, J. A pragmatic definition of the concept of theoretical saturation. Sociol. Focus 2019, 52, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linneberg, M.S.; Korsgaard, S. Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qual. Res. J. 2019, 19, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, P.M. Qualitative Research Methods in Consumer Psychology: Ethnography and Culture; Routledge Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, P.M.; Schwarzenbach, J.B.; Jürgens, U.M. Consumer Psychology: A Study Guide to Qualitative Research Methods; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Selting, M.; Auer, P.; Barth-Weingarten, D.; Bergmann, J.; Bergmann, P.; Birkner, K.; Couper-Kuhlen, E.; Deppermann, A.; Gilles, P.; Günthner, S.; et al. Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2 (GAT 2). Gesprächsforschung 2009, 10, 353–402. [Google Scholar]

- Oevermann, U.; Allert, T.; Konau, E.; Krambeck, J. Die Methodologie einer ‘objektiven Hermeneutik’ und ihre allgemeine Forschungslogische Bedeutung in den Sozialwissenschaften. In Interpretative Verfahren in den Sozial—Und Textwissenschaften; Soeffner, H.-G., Ed.; J.B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung: Stuttgart, Germany, 1979; pp. 352–433. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, H.L. The second step in data analysis: Coding qualitative research data. J. Soc. Health Diabetes 2015, 3, 007–010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mey, G.; Mruck, K. Grounded Theory Reader; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Benoot, C.; Hannes, K.; Bilsen, J. The use of purposeful sampling in a qualitative evidence synthesis: A worked example on sexual adjustment to a cancer trajectory. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fischer, C.T. Bracketing in qualitative research: Conceptual and practical matters. Psychother. Res. 2009, 19, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufford, L.; Newman, P. Bracketing in qualitative research. Qual. Soc. Work. 2012, 11, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc. Probl. 1965, 12, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, P.M. A Reflexive and Adaptable Framework for Ethnographicand Qualitative Research: The Declarative MappingSentences Approach. Acad. Lett. 2021, 999. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429320927-11/declarative-mapping-sentence-framework-conducting-ethnographic-health-research-paul-hackett (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Blekesaune, A.; Rønningen, K. Bears and fears: Cultural capital, geography and attitudes towards large carnivores in Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift Nor. J. Geogr. 2010, 64, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wallner, A.; Hunziker, M. Die Kontroverse um den Wolf–Experteninterviews zur gesellschaftlichen Akzeptanz des Wolfes in der Schweiz. For. Snow Landsc. Res. 2001, 76, 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Slagle, K.M.; Wilson, R.S.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Toman, E. The symbolic wolf: A construal level theory analysis of the perceptions of wolves in the United States. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 32, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, O.I. Der Wolf und das Waldviertel: Sozial-ökologische Betrachtung der Mensch-Wolf-Interaktion. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Natural Resources & Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arbieu, U.; Albrecht, J.; Mehring, M.; Bunnefeld, N.; Reinhardt, I.; Mueller, T. The positive experience of encountering wolves in the wild. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisi, J.; Liukkonen, T.; Mykrä, S.; Pohja-Mykrä, M.; Kurki, S. The good bad wolf—wolf evaluation reveals the roots of the Finnish wolf conflict. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres, R.T.; Lopes, D.; Fonseca, C.; Rosalino, L.M. One rule does not fit it all: Patterns and drivers of stakeholders perspectives of the endangered Iberian wolf. J. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 55, 125822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogen, K.; Krange, O. The Political dimensions of illegal wolf hunting: Anti-elitism, lack of trust in institutions and acceptance of illegal wolf killing among Norwegian hunters. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 60, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.C.; Radke, H.R.; Kutlaca, M. Stopping wolves in the wild and legitimizing meat consumption: Effects of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance on animal-related behaviors. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2019, 22, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S.C.; Dietsch, A.M.; Slagle, K.M.; Bruskotter, J.T. The VIPs of wolf conservation: How values, identity, and place shape attitudes toward wolves in the United States. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunziker, M.; Hoffmann, C.W.; Wild-Eck, S. Die Akzeptanz von Wolf, Luchs und Stadtfuchs—Ergebnisse einer gesamtschweizerisch-repräsentativen Umfrage. For. Snow Landsc. Res. 2001, 76, 301–326. [Google Scholar]

- Grima, N.; Brainard, J.; Fisher, B. Are wolves welcome? Hunters’ attitudes towards wolves in Vermont, USA. Oryx 2021, 55, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. Hierarchy, Intrusion, and the Anthropomorphism of Nature: Hunter and Rancher Discourse on North American Wolves. In A Fairytale in Question: Historical Interactions between Humans and Wolves; Masius, P., Sprenge, J., Eds.; The White Horse Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 282–303. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Bjerke, T. The relationship of general life values to attitudes toward large carnivores. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2002, 9, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens, U.M. How human-animal relations are realized: From respective Realities to merging minds. Ethics Environ. 2017, 22, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestel, D. What capabilities for the animal? Biosemiotics 2011, 4, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, U.M. “I am Wolf, I Rule!”-Attributing Intentions to Animals in Human-Wildlife Interactions. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2022, 3, 803074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevillano, V.; Fiske, S.T. Stereotypes, emotions, and behaviors associated with animals: A causal test of the Stereotype Content Model and BIAS Map. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2019, 22, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, U.M.; Grinko, M.; Szameitat; Hieber, L.; Fischbach, R.; Hunziker, M. Managing Wolves is managing Narratives: Views of Wolves and Nature spawn People’s Proposals for navigating Human-Wolf Relations. Hum. Ecol. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Figari, H.; Skogen, K. Social representations of the wolf. Acta Sociol. 2011, 54, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, M.; Hiedanpää, J.; Luoma, M.; Pellikka, J. Nudging the impasse? Lessons from the nationwide online wolf management forum in Finland. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2017, 30, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruskotter, J.T.; Fulton, D.C. Will hunters steward wolves? A comment on Treves and Martin. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 25, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tønnessen, M. Historicising the Cultural Semiotics of Wolf and Sheep. Pak. J. Hist. Stud. 2016, 1, 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, A. Human Dimensions in Wolf Management in Savoie and Des Alpes Maritimes, France; France LIFE-Nature Project, Le retour du loup dans les Alpes Françaises, & the Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe (LCIE); Memorial University of Newfoundland, Dep. Of Geography: St. John’s, NL, Canada, 2000; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238096165_Human_Dimensions_in_Wolf_Management_in_Savoie_and_Des_Alpes_Maritimes_France (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Dingwall, S. Ravenous wolves and cuddly bears: Predators in everyday. For. Snow Landsc. Res. 2001, 76, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, B. Raubtiere, Mythologisch und Tiefenpsychologisch Betrachtet. In Humans and Predators in Europe—Research on How Society Is Coping with the Return of Wild Predators. Forest Snow and Landscape Research; Hunziker, M., Landolt, R., Eds.; Forest Snow and Landscape Research: Birmensdorf, Switzerland, 2001; Volume 76, pp. 53–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sevillano, V.; Fiske, S.T. Warmth and competence in animals. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyne, J.; Abildtrup, J.; Maréchal, K. The wolves are coming: Understanding human controversies on the return of the wolf through the use of socio-cultural values. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2021, 67, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Essen, E.; Allen, M. ‘Not the Wolf Itself’: Distinguishing Hunters’ Criticisms of Wolves from Procedures for Making Wolf Management Decisions. Ethics Policy Environ. 2020, 23, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meurer, H.; Richarz, K. Von Werwölfen und Vampiren; Kosmos: Stuttgart, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Würdinger, I. Raben und Krähen als Sinnbilder, Proceedings of the Artenschutzsymposium Saatkrähe, Fachhochschule Nürtingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, 15–16 March 1986; Landesanstalt für Umweltschutz Baden-Württemberg, Institut für Ökologie und Naturschutz, Eds.; Beihefte zu den Veröffentlichungen für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege in Baden-Württemberg; Fachhochschule Nürtingen: Baden-Württemberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Riechelmann, C. Krähen; Matthes & Seiz: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hereth, A. Das Bild der Rabenvögel (Corvidae) in der heutigen Gesellschaft. Eine Erhebung von Wissen und Einstellungen zu den Rabenvögeln am Rande einer öffentlichen Diskussion. Ph.D. Thesis, Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, Giessen, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, M. Are animals persons? Anim. Sentience Interdiscip. J. Anim. Feel. 2016, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despret, V. The Enigma of the Raven. Angelaki J. Theor. Humanit. 2015, 20, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Kinship to Mastery: Biophilia in Human Evolution and Development; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, H.M.; Gray, K.; Wegner, D.M. Dimensions of mind perception. Science 2007, 315, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waytz, A.; Morewedge, C.K.; Epley, N.; Monteleone, G.; Gao, J.-H.; Cacioppo, J.T. Making sense by making sentient: Effectance motivation increases anthropomorphism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 99, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegel, B. Tiere in der Stadt: Eine Naturgeschichte; DuMont Buchverag: Cologne, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Felthous, A.R.; Kellert, S.R. Psychosocial aspects of selecting animal species for physical abuse. J. Forensic Sci. 1987, 32, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, K.Z.; Stefan, R. Lauter schwarze Spinnen—Spinnenmotive in der deutschen Literatur—Eine Sammlung; Bouvier Verlag: Bonn, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, S.; Radhakrishna, S. Investigating trends in human-wildlife conflict: Is conflict escalation real or imagined? J. Asia-Pac. Biodivers. 2017, 10, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Public Perceptions of Predators, Particularly the Wolf and Coyote. Biol. Conserv. 1985, 31, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A. Factors influencing human attitudes to animals and their welfare. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverri, A.; Karp, D.S.; Naidoo, R.; Zhao, J.; Chan, K.M. Approaching human-animal relationships from multiple angles: A synthetic perspective. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 224, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greider, T.; Garkovich, L. Landscapes: The Social Construction of Nature and the Environment. Rural. Sociol. 1994, 59, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.A. The wolf in Yellowstone: Science, symbol, or politics? Deconstructing the conflict between environmentalism and wise use. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1997, 10, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callicott, J.B. Environmental Ethics: I. Overview. In Encyclopedia of Bioethics; Post, S., Ed.; Macmillan Reference USA: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 757–769. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. The value basis of environmental concern. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.C.G.; Barton, M.A. Ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes toward the environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1994, 14, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietsch, A.; Manfredo, M.; Teel, T. Wildlife Value Orientations As an Approach to Understanding the Social Context of Human–Wildlife Conflict. In Understanding Conflicts about Wildlife: A Biosocial Approach; Hill, C.M., Webber, A.D., Priston, N.E.C., Eds.; Berghan: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 174–204. [Google Scholar]

- Teel, T.L.; Manfredo, M.J. Understanding the diversity of public interests in wildlife conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaver, I.; Keulartz, J.; Van Den Belt, H. Born to be Wild: A Pluralistic Ethics Concerning Introduced Large Herbivores in the Netherlands. Environ. Ethics 2002, 24, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callicott, J.B. Animal liberation and environmental ethics: Back together again. Between Species 1988, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapron, G.; Kaczensky, P.; Linnell, J.D.C.; von Arx, M.; Huber, D.; Andrén, H.; López-Bao, J.V.; Adamec, M.; Álvares, F.; Anders, O.; et al. Recovery of large carnivores in Europe’s modern human-dominated landscapes. Science 2014, 346, 1517–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mace, G.M. Whose conservation? Science 2014, 345, 1558–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietsch, A.M.; Teel, T.L.; Manfredo, M.J. Social values and biodiversity conservation in a dynamic world. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.C.; Dhont, K.; Hodson, G. Longitudinal effects of human supremacy beliefs andvegetarianism threat on moral exclusion (vs. inclusion) of animals. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ingold, T. From the master’s point of view: Hunting is sacrifice. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2015, 21, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMotts, R.; Hoon, P. Whose elephants? Conserving, compensating, and competing in northern Botswana. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 25, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Karlsson, J. Subjective Experience of Fear and the Cognitive Interpretation of Large Carnivores. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2011, 16, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Karlsson, J.; Pedersen, E.; Flykt, A. Factors governing human fear of brown bear and wolf. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2012, 17, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.H.; Barrett, J. The role of control in attributing intentional agency to inanimate objects. J. Cogn. Cult. 2003, 3, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunziker, M.; Egli, E.; Wallner, A. Return of predators: Reasons for existence or lack of public acceptance. KORA Bericht 1998, 3, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, J.M.; Cooper, H.M. The desirability of control. Motiv. Emot. 1979, 3, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. First World political ecology: Lessons from the Wise Use movement. Environ. Plan. A 2002, 34, 1281–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Contemporary Values of Wildlife in American Society. In Wildlife Values; Shaw, W.W., Zube, E.H., Eds.; U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mt Forest and Range Experiment Station, Center for Assessment of Noncommodity Natural Resource Values, Fort Collins: Colorado, CO, USA, 1980; pp. 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith, N.; Kerley, G.I.H.; Page, B.; Slotow, R.; van Aarde, R.J. A scientific perspective on the management of elephants in the Kruger National Park and elsewhere. South Afr. J. Sci. 2006, 102, 389–394. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, M.N.; Birckhead, J.L.; Leong, K.; Peterson, M.J.; Peterson, T.R. Rearticulatingthe myth of human–wildlife conflict. Conserv. Lett. 2010, 3, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotulski, Y.; König, A. Conflicts, crises and challenges: Wild boar in the Berlin City–a social empirical and statistical survey. Nat. Croat. Period. Musei Hist. Croat. 2008, 17, 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerke, T.; Østdahl, T. Animal-related attitudes and activities in an urban population. Anthrozoös 2004, 17, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, A.; Flykt, A.; Esteves, F. Emotion drives attention: Detecting the snake in the grass. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2001, 130, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.J. “Bats, snakes and spiders, Oh my!” How aesthetic and negativistic attitudes, and other concepts predict support for species protection. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G. The Handbook of Contemporary Animism; Harvey, G., Ed.; Acumen: Durham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sevillano, V.; Fiske, S. Animals as Social Groups: An Intergroup Relations Analysis of Human-Animal Conflicts. In Why We Love and Exploit Animals: Bridging Insights from Academia and Advocacy; Dhont, K., Hodson, G., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 254–276. [Google Scholar]

- De Waal, F.B. Anthropomorphism and anthropodenial: Consistency in our thinking about humans and other animals. Philos. Top. 1999, 27, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.T. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waytz, A.; Gray, K.; Epley, N.; Wegner, D.M. Causes and consequences of mind perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruskotter, J.T.; Wilson, R.S. Determining Where the Wild Things will be: Using Psychological Theory to Find Tolerance for Large Carnivores. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 7, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flykt, A.; Johansson, M.; Karlsson, J.; Lindeberg, S.; Lipp, O.V. Fear of Wolves and Bears: Physiological Responses and Negative Associations in a Swedish Sample. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2013, 18, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.; Johansson, M.; Flykt, A. Public attitude towards the implementation of management actions aimed at reducing human fear of brown bears and wolves. Wildl. Biol. 2015, 21, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, A.; Mineka, S. Fears, phobias, and preparedness: Toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 108, 483–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adams, W.M. The Political Ecology of Conservation Conflicts. In Conflicts in Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, E.; Di Masso, A.; Castrechini, A.; Bonet, M.; Vidal, T. Psychological parameters to understand and manage the NIMBY effect. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 56, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, V. The concept of a cultural landscape: Nature, culture and agency of the land. Ethics Environ. 2006, 11, 115–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnell, J.D.C.; Kaczensky, P.; Wotschikowsky, U.; Lescureux, N.; Boitani, L. Framing the relationship between people and nature in the context of European conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bjerke, T.; Vitterso, J.; Kaltenborn, B.P. Locus of control and attitudes toward large carnivores. Psychol. Rep. 2000, 86, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, I.; Jonas, E.; Fankhänel, T. The role of control motivation in mortality salience effects on ingroup support and defense. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.; Pyszczynski, T.; Solomon, S.; Rosenblatt, A.; Veeder, M.; Kirkland, S.; Lyon, D. Evidence for terror management theory II: The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who threaten or bolster the cultural worldview. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, A.; Greenberg, J.; Solomon, S.; Pyszczynski, T.; Lyon, D. Evidence for terror management theory: I. The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who violate or uphold cultural values. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants’ Life Themes through the Lens of Which They View the Relation to the Wildlife Species | Utopian Visions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| An Extended Family Embracing Humankind, Wildlife, and Nature | A Traditional Human–Nature Relationship Based on Sustainable Use | A Cohesive Society Based on Tribal Structures, Solidarity, and Respect | ||

| The relation of humans to the wildlife species pinpoints the relationship between humans and nature more generally. | ||||

| W1 | His life theme, as an influential animal rights lobbyist, is fighting against a presumed annihilating intention that people direct towards animals in general which gets actualized specifically in anti-wolf sentiments. | The Kantian imperative acts as the ethical base for treating beings of all species as if they were family members. | ||

| C2 | He charges modern people’s allegedly ubiquitous unwillingness to accommodate inconveniences of all kinds, which also causes them to oppose the presence of corvids in their proximity. | The revival of traditional farming be a cure for environmental, social and health issues. | ||

| C5 | She reports to have suffered immensely from human hard-heartedness in her life and sees her suffering as being mirrored in the crows who are treated cruelly by people. | A Christian paradisiac ideal of harmony among all beings. | ~ | |

| S1 | ~ | All species be released from the metabolic cycle, so a cruelty-free interbeing may ensue. | ||

| S4 | Being a Christian deacon, her life is oriented towards worshiping the whole of creation. In her view, her arachnophobia and the controlling measures she takes starkly contradict her moral code. This quandary distresses her on a daily basis. | ~ | ||

| S6 | Perfused by epistemological striving, he considers fractality a building block of the universe. Perceiving it in a spider’s web struck him in an epiphany about the oneness of all beings, thus soothing his aching search for humanity’s place within nature. | ~ | ||

| S7 | As a scientist investigating spiders, he still regards them as only one link in the global ecosystem. However, he views the human–spider relationship as the epitome of human intrusiveness that needs to be obverted. | ~ | ||

| The wildlife species evidences the necessity for humans to manage nature, particularly to control wildlife population density. | ||||

| W2 | He claims that as a general rule of existence, organisms and technical developments will propagate boundlessly and must be regulated by humans—including wolves, who need to be controlled though hunting. | |||

| W6 | He shows the demeanor of a traditional patriarch towards his wife and horses whom he regards as extended family. He owns a large property whose ecological value he carefully maintains according to ecocentric values from which wolves and magpies are selectively exempted. He advocates for the eradication of all wolves from Germany and culling of magpies. | ~ | ||

| C3 | Being a passionate hunter and hunting lobbyist, he is devout to the conviction that in the present landscape which has been significantly altered by humans, management though hunting is pivotal for establishing and maintaining a balance and diversity of species. He takes corvids, as hemerophiles, to be the epitome of this general principle. | Restoring a diversity of game that parallels those of traditional mid-European hunting grounds from “my granddad’s times” | ||

| The ways in which humans deal with the wildlife species allegorize general deficits in society and in the political arena. | ||||

| W3 | An independent-minded entrepreneur, he scornfully accuses politicians and authorities of incompetence and hypocrisy. The ways in which the responsible parties deal with wolves evidence the general issues of wasted taxpayers’ money, crookedness among his fellow hunters, and societal egocentrism. | ~ | ||

| W4 | Portraying himself as a responsible hunter, he loathes the legal framework restraining hunters from enacting their free will within their hunting ground. Wolves epitomize the encroachments on hunters’ sovereignty. | |||

| W7 | Based on his experience in the political arena as a member of parliament and wise-use lobbyist, he proposes that debates on wolves evidence fundamental problems in the German mindset and political system: an interest in power instead of in resolving practical challenges; putting ideology first and reality-checks second; an alienation of the societal majority from urban lifeways; and a failure to act on humans’ quasi-sacred responsibility for managing and thus maintaining the cultural landscape. | |||

| C4 | An ecologically minded shepherd providing environmental education for children, she meets many administrative hurdles and policy-induced economic challenges in addition to the natural imponderables such as predation by wolves and corvids on her sheep. She suffers from the system being profit-oriented rather than supportive of ecologically and socially meaningful vocations such as hers. | ~ | Human society being intimately connected with nature in a cultural landscape allowing unrestricted roaming for livestock and wildlife. | |

| S3 | He sees an allowing and respectful handling of spiders as an allegory for the appreciation and loyalty in human society that is to be aspired, but allegedly has deteriorated in modern times. | He extrapolates his childhood experience of growing up on his grandparents’ farm to a mythical past and to an envisioned future of humankind that are characterized by granting autonomy yet ensuring solidarity to all individual members of the social group. | ||

| S5 | Having grown up in North Rhine-Westphalia and worshiping the Viking culture, he holds strong views with regard to what qualifies a worthy person. He purports that a person’s nature is evidenced through the way in which they treat spiders, which also parallel the ways in which they will treat other animals and their fellow humans. | ~ | A vision for society based on assumptions about the character of the Westphalian “race” and Viking tribalism: loyalty, toughness, self-assertion, and respectful demeanor to all life forms. | |

| Themes | Wolves Critical | Wolves Favorable | Corvids Critical | Corvids Favorable | Spiders Critical | Spiders Favorable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| useful–not useful | Wolves cause damage, while their presence serves no purpose. (W2, W4, W5, W6, C2, C4) Being apex predators both, wolves and human hunters compete for game and potentially render hunting unnecessary and unfeasible. (W2, W3, W4, W5, C3) Wolves are not good managers of game populations. (W2, W6) | The presence of wolves may be beneficial for hunters as it enriches the ecosystem and renders the experience of the hunt more exciting. (W3, W7, C2, C3) | Corvids are vermin causing nuisances. (C3, W4) Corvids cause noise. (C1, C2, C5, C6, S4) Corvids empty trash cans. (C1, C6) Corvids befoul pavements and cars. (C2, C6) Corvid depredation endangers small game and other bird species. (C3, C6) | Rooks are potentially useful, e.g., when devouring crop pests. (C3) | Spiders are considered vermin and a potential “problem of hygiene”(S6) to get rid of as part of tending to one’s home. (S4, S5, S6) Spiders cannot be put to use by humans. (S4) | Spiders are useful and diligent, e.g., in devouring pests such as mosquitoes. (S1, S4, S5, S6) Spiders are quiet beings. (S4) |

| Wolves are a constant threat to livestock despite protection measures. Their presence impedes farmers from responsibly caring for their livestock. Given the emotional connection of farmers to livestock, they threaten farmers’ mental wellbeing. (W4, W6, W7, C4) | Wolves’ depredation on livestock is to be accepted as a natural phenomenon. (W1, W3, C4, S2) | Corvids kill newborn livestock. (C4) Corvids devour seedlings. (W4) | ||||

| dangerous–harmless | Wolves are dangerous to humans. (W2, W5, W6, C2, C3) | Wolves will only be dangerous to humans under exceptional circumstances, e.g., if injured. (W1, W3, W4, W7, S2) | Corvids could harm humans, e.g., with their strong beak. (C1, C4) | Spiders evoke fear due to their (seeming) ability to harm humans. (S1, S3, S4, S6) | Spiders are harmless. (S2, S4, S6, S7) | |

| Wolves emanate a sense of constant, omnipresent threat. (W6, C4) | The presence of corvids emanates a sense of threat. (C4, C6) Corvids’ presence is reminiscent of Hitchcock’s The Birds. (C4, C6) | Spiders can appear anywhere any time; they seem to be omnipresent—thus scaring arachnophobes even if not seen. (S1, S4, S6) | ||||

| (un)controllable | Wolves reproduce boundlessly if not controlled. (W2, W4, W5, W6) Wolf numbers must be capped. (W3, W7) | Corvid numbers have risen constantly and significantly. (C3, C4, C6) Corvid numbers must be reduced to keep a natural balance. (C3) | ||||

| Wolves’ behavior cannot be controlled. (W2) Wolves are impudent, must be “kept in check“. (W2, W6, C4) Wolves do not flee in human presence (W7) | Wolves cannot be domesticated. (W1) Wolves are nocturnal. (W2, W3) Wolves are shy and evade human presence. (W1, W2, W4) | By flying, corvids master the third dimension, making them even harder to control. (C4, C6) Corvids behave impudently in coming close to humans. (C4, C6) | The unpredictability and speed of spiders’ movement are unsettling; particularly their sudden appearance near to a person is fearsome. (S1, S2, S4, S6, S7) Killing spiders is an involuntary response for restoring control. (S1, S4, S6) | Spiders’ mastery the third dimension with their web-weaving is similar to a superpower. (S4, S6) | ||

| Corvids’ agency is salient since they appear to be always on the go, playful, and full of joie de vivre. (C1, C5) | Spiders exhibit deliberate and intentional behaviors. (S3, S6) | |||||

| (un) social | Wolves’ living in social groups makes their impact particularly problematic. (W2, W4) | Wolves are caring, social beings and have families, just as humans do. (W1) | Corvids wrangle with each other. (C6) | Corvids are social beings exhibiting loyalty, loving relationality, and caring towards their kin and other species, including humans, Thus, they are models for humankind. (C3, C5, S6) | Spiders are utterly alien to humans in their ways of being; no mutual understanding or communication is feasible. (S2, S4, S5, S6, S7, C1) | Humans and spiders may share a sense of mutual apperception that, at least on the part of the human, can be seen as relationality. (S3, S4, S5, S6) |

| (un)aesthetic | Wolves are unaesthetic. (W4) | Wolves are beautiful. (W2, W7) | Corvids’ blackness is a salient and potentially uncanny feature. (C1, C3, C4, C6, S4) | Corvids are beautiful, impressive beings, particularly because of their size. (C1, C5, C6) | Spiders are not seen as being cute by most people. (S2) Spiders are prototypically represented as being dark. (S4, S6) | Spiders are aesthetic beings. (S2, S7) |

| ambivalent fascination | Wolves are fascinating, numinous, awe-inspiring beings. (W1, W7, C2, C3) | Corvids are fascinating to watch. (C1, C3, C6) Corvids are numinous, awe-inspiring creatures. (C5, C6) | Spiders evoke a distancing response (a mild sense of disgust and fear) even in people not particularly opposed to them. (S2, S6, S7) | Spiders and their lifeways (e.g., web-weaving) are fascinating, numinous, awe-inspiring, and daunting. (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5 S6, S7) Spiders’ strangeness bestows a sense of specialness onto humans associated with them. (S2, S3, S4) | ||

| intelligent and capable | Wolves are capable of calculating, strategic moves. (W6, W7) | Wolves are intelligent and can learn quickly. (W1, C4) | Corvids are intelligent, knowledgeable and wise. (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, W4, S6) Corvids appear to have a perspective of their own. (C1, C3, C5’) Corvids have epistemological interests. (C1) | Spiders may be endowed with an ancient wisdom. (S1, S6) Spiders exhibit a great deal of creativity and deliberate artistry in web-weaving. (S4, S6) | ||

| Wolves are opportunists and adapt to different circumstances. (W3, W7) | Corvids are opportunistic profiteers of the human-made landscape and bohemians exhibiting a “toughness” in getting along. (C3) | Spiders are persevering in the face of adversity. (S4) | ||||

| morally condemnable | Wolves perform excessive surplus kills. (W4, W6) Wolves kill particularly cold-heartedly, cruelly, as “killers” (W2; W4, W6, W7) Wolves are akin to “criminals“. (W6, C4) Wolves are ever-hungry beasts. (W2) | Corvids are cold-blooded “killers” of lambs and small game. (C3, C4) Corvids are similar to “terrorists” and “rapists”. (C4) | Spiders evoke an amorphous impression of being evil creatures. (S1, S5, S7) Spiders pursue a predatory lifestyle. (S4) | |||

| disgusting | Corvids are associated with filth, e.g., waste dumps and decaying corpses. (C1, C3) | Spiders evoke disgust, particularly due to the shape and proportions of their bodies. (S1, S3, S4, S6, S7) The larger the spider, the greater feelings of disgust and fear. (S1, S2, S4, S6, S7) | ||||

| (not) belonging | Wolves do not belong to and should be kept out of Central Europe. (W6) Wolves have their place in nature, not in the cultural landscape. (W2, W3, W4, W7, C2) | Wolves are an integral part of the ecosystem and have been and are meant to be part of Central European landscapes. (W1) | As hemerophilic wild animals, corvids populate an intermediate realm between nature and the human sphere. (C1, C3, C5) Rooks’ presence is an indicator of a healthy ecosystem. (C2) | |||

| nature | Wolves epitomize the fact that nature can be cruel. (C4, C5) | Wolves are symbols for pristine nature, wilderness, and for the resilience of nature. (W1, W7) | Corvids can be brutal and thus evidence the fact that nature can be cruel. (C2, C3, C4, C5) | Spiders are primordial beings, and symbols for life, i.a., due to the evolutionary persistence of their class. (S3, S5, S6, S7) | ||

| poise | Wolves are symbols of strength and assertiveness. (W1, W7) | Corvids appear regal and self-conscious. (C1, C5) | Spiders have a lordly appearance. (S2, S2) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jürgens, U.M.; Hackett, P.M.W.; Hunziker, M.; Patt, A. Wolves, Crows, Spiders, and People: A Qualitative Study Yielding a Three-Layer Framework for Understanding Human–Wildlife Relations. Diversity 2022, 14, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080591

Jürgens UM, Hackett PMW, Hunziker M, Patt A. Wolves, Crows, Spiders, and People: A Qualitative Study Yielding a Three-Layer Framework for Understanding Human–Wildlife Relations. Diversity. 2022; 14(8):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080591

Chicago/Turabian StyleJürgens, Uta M., Paul M. W. Hackett, Marcel Hunziker, and Anthony Patt. 2022. "Wolves, Crows, Spiders, and People: A Qualitative Study Yielding a Three-Layer Framework for Understanding Human–Wildlife Relations" Diversity 14, no. 8: 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080591

APA StyleJürgens, U. M., Hackett, P. M. W., Hunziker, M., & Patt, A. (2022). Wolves, Crows, Spiders, and People: A Qualitative Study Yielding a Three-Layer Framework for Understanding Human–Wildlife Relations. Diversity, 14(8), 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080591