Daily Life in the Limesgebiet: Archaeozoological Evidence on Animal Resource Exploitation in Lower Danubian Sites of 2nd–6th Centuries AD

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Study Area: The Roman Limes in Dobrudja

1.2. Settlements under Archaeozoological Study: Archaeological Context

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

| Sample | Taxonomic Group | Mollusca (Molluscs) | Pisces (Fish) | Reptilia (Reptiles) | Aves (Birds) | Mammalia (Mammals) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halmyris 4th–7th centuries AD [24,25] | NISP | 9 | 0 | 0 | 87 | 3457 | 3553 |

| % | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 2.45 | 97.3 | 100 | |

| Halmyris 4th–6th centuries AD (Stanc, unpublished data) | NISP | 12 | 169 | 3 | 9 | 2014 | 2207 |

| % | 0.54 | 7.66 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 91.26 | 100 | |

| Sacidava 4th–6th centuries AD (Stanc, unpublished data) | NISP | 0 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 438 | 447 |

| % | 0 | 1.57 | 0 | 0.45 | 97.99 | 100 | |

| Capidava 4th–6th centuries AD [26] | NISP | 0 | 14 | 0 | 3 | 161 | 178 |

| % | 0 | 7.86 | 0 | 1.69 | 90.45 | 100 | |

| Dinogetia 4th–6th centuries AD [27] | NISP | 16 | 28 | 0 | 7 | 129 | 180 |

| % | 8.89 | 15.55 | 0 | 3.89 | 71.67 | 100 | |

| Aegyssus 3rd–5th centuries AD (Stanc, unpublished data) | NISP | 2 | 107 | 0 | 7 | 1113 | 1229 |

| % | 0.16 | 8.71 | 0 | 0.57 | 90.6 | 100 | |

| Noviodunum 2nd–4th centuries AD [28] | NISP | 0 | 66 | 0 | 36 | 1132 | 1234 |

| % | 0 | 5.35 | 0 | 2.92 | 91.73 | 100 | |

| Noviodunum 2nd–3rd centuries AD [29,30] | NISP | 0 | 12 | 0 | 10 | 350 | 372 |

| % | 0 | 2.69 | 0 | 3.23 | 94.08 | 100 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fündling, J. Kommentar zur Vita Hadriani der Historia Augusta. Antiquitas 2006, 4, 609–612. [Google Scholar]

- Țentea, O. About the Roman frontier on the Lower Danube under Trajan. In Moesica et Christiana. Studies in Honour of Professor Alexandru Barnea; Panaite, A., Cîrjan, R., Carol Căpiță, C., Eds.; Editura Istros: Brăila, Romania, 2016; pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Liușnea, M.D. Considerații privind limes-ul roman în perioada Principatului, la Dunărea de Jos. Carpica 2000, 29, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Aricescu, A. Armata în Dobrogea romană; Editura Militară: București, Romania, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Condurachi, E. Classis Flavia Moesica au Ier siècle de n.è. In Actes du IX-e Congrès International D’études sur les Frontières Romaines, Mamaia, Romania, 6–13 Septembre 1972; Editura Academiei RSR: București, Romania, 1974; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnowski, T. Ti. Plautius Silvanus, Tauric Chersonesos and Classis Moesica. Dacia 2006, 50, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, M. Towards a Military Geography of Moesia Inferior. In Bulletin of the National Archaeological Institute XLII. LIMES XXII: Proceedings of the 22nd International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies, Ruse, Bulgaria, September 2012; Vagalinski, L., Sharankov, N., Eds.; National Archaeological Institute with Museum: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2015; pp. 845–852. [Google Scholar]

- Suceveanu, A. În legătură cu data anexării Dobrogei de către romani. Pontica 1971, 4, 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Teodor, E.S. The Border area between Moesia Secunda and Scythia Minor in a topographical approach. In Identități Culturale Locale și Regionale în Context European. Studii de Arheologie și Antropologie Istorică. In Memoriam Alexandri V. Matei; Bacuet, C.D., Pop, H., Bejinariu, I., Eds.; Editura Mega: Cluj Napoca, Romania, 2010; pp. 421–438. [Google Scholar]

- Stoian, I.; Suceveanu, A. (Eds.) Inscripţiile din Scythia Minor, Greceşti şi Latine. II. Tomis şi Teritoriul Său; Editura Academiei RSR: Bucureşti, Romania, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zahariade, M. Moesia Secunda, Scythia și Notitia Dignitatum; Editura Academiei: București, Romania, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, A. Organizarea administrativă. Orașe și târguri. In Istoria Românilor. Daco-Romani, Romanici, Alogeni; Protase, D., Suceveanu, A., Eds.; Editura Enciclopedică: București, Romania, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 485–492. [Google Scholar]

- Băjenaru, C. Minor Fortifications in the Balkan–Danubian Area from Diocletian to Justinian; Editura Mega: Cluj Napoca, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Madgearu, A. The end of the Lower Danube limes: A violent or a peaceful process? Studia Antiq. Et Archaeol. 2006, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Colesniuc, S.; Potârniche, T.; Mototolea, A.; Cliante, T.; Stanc, S. Intramuros archaeological research at Sacidava. Preliminary information. In ArheoVest VIII. Interdisciplinaritate în Arheologie. In Honorem Alexandru Rădulescu; Forțiu, S., Micle, D., Eds.; JATE-Press Kiadó: Szeged, Hungary, 2020; pp. 375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Petculescu, L. The Roman Army as a Factor of Romanisation in the North-Eastern Part of Moesia Inferior. In Rome and the Black Sea Region: Domination, Romanisation, Resistance; Bekker-Nielsen, T., Ed.; Aarhus University Press: Aarhus, Denmark, 2006; pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Scorpan, C. Sacidava și unele probleme stratigrafice și cronologice ale limes-ului Dobrogei romane. (Secolul V e.n. în arheologia dobrogeană). Pontica 1972, 5, 301–327. [Google Scholar]

- Vagalinski, L. The Problem of Destruction by Warfare in Late Antiquity: Archaeological Evidence from the Danube limes. In The Lower Danube Roman Limes (1st–6th C. AD); Vagalinski, L., Sharankov, N., Torbatov, S., Eds.; National Archaeological Institute with Museum: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2012; pp. 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- Doruţiu-Boilă, E. (Ed.) Inscripţiile din Scythia Minor, Greceşti şi Latine. V. Capidava-Troesmis-Noviodunum; Editura Academiei RSR: Bucureşti, Romania, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Țentea, O.; Opriș, I.C.; Matei-Popescu, F.; Rațiu, A.; Băjenaru, C.; Călina, V. Frontiera romană din Dobrogea. O trecere în revistă și o actualizare. Cercet. Arheol. 2019, 26, 9–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorpan, C. Limes Scyhiae. Topographical and Stratigraphical Research on the Late Roman Fortifications on the Lower Danube; BAR International Series 88; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Suceveanu, A.; Zahariade, M. Un nouveau vicus sur le territoire de la Dobroudja romaine. Dacia 1986, 30, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Udrescu, M.; Bejenaru, L.; Hriscu, C. Introducere în Arheozoologie; Editura Corson: Iași, Romania, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- El Susi, G. Data about hunting practices by Halmiris (Murighiol, Tulcea County) inhabitants in 4th–7th centuries AD. Cult. Şi Civ. La Dunărea De Jos 2008, 24, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- El Susi, G. Animal breedind in late Roman settlements from Dobrudja, in the light of research at Murighiol (Halmyris, Tulcea county). Cult. Şi Civ. La Dunărea De Jos 2011, 28, 170–189. [Google Scholar]

- Haimovici, S.; Cărpuş, L.; Cărpuş, C. Studiul arheozoologic al unui lot de faună provenit din situl romano-bizantin de la Capidava–sec. IV-VI p.Chr. Pontica 2006, 39, 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Haimovici, S. Studiul arheozoologic al resturilor de la Dinogetia (Garvăn), aparţinând epocii romane târzii. Peuce 1991, 10, 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Stanc, S.; Stănică, A.D.; Bejenaru, L.; Danu, M. Archaeological animal remains from Noviodunum fortress. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 12, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Stanc, S.; Bejenaru, L. Archaeozoological analysis of a sample of Roman period in the Isaccea site. An. Ştiințifice Ale Univ. Al.I. Cuza Iaşi 2009, 55, 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Stanc, S.; Bejenaru, L. Animal resources exploited in settlements of the 2nd–7th centuries in the area between Danube and Black Sea: Archaeozoological data. Istros 2013, 19, 389–409. [Google Scholar]

- Ervynck, A.; Vanderhoeven, A. Tongeren (Belgium): Changing patterns of meat consumption in a roman civitas capital. Anthropozoologica 1997, 25–26, 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Deschler-Erb, S. Animal Husbandry in Roman Switzerland: State of Research and New Perspectives. Eur. J. Archaeol. 2017, 20, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović, M.; Pop-Lazić, S. Animal Management in the Fortified Palace Felix Romuliana–Gamzigrad (Serbia) Throughout the Late Antique and the Early Byzantine Periods. In ICAZ-Zooarchaeology of the Roman Period–3rd Working Group Meeting: Animals in the Roman Economy: Production, Supply, and Trade within and beyond the Empire’s Frontiers; University College Dublin: Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Makowiecki, D. Animal economy in the microregion of Novae in the light of its archaeozoological data. In Der Limes an der Unteren Donau von Diokletian bis Heraklios; Internationalen Konferenz Svistov, Bulgaria, 1–5 September 1998; von Bulow, G., Mulceva, A., Eds.; Nous Publishers: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1999; pp. 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, A.B.; Klenina, E. The Roman legionary camp and Early-Byzantine town of Novae (Moesia Inferior/Moesia Secunda) after six years of research. Novae. Stud. Mater. 2022, VIII, 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Makowiecki, D.; Makowiecka, M. Animal remains from the 1989, 1990, 1993 excavations of Novae (Bulgaria). In The Roman and Late Roman City. The International Conference (Veliko Tarnovo, 26-30 July 2000); Prof. Marin Drinov Academic Publishing House: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2012; pp. 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Beech, M. The economy and environment of a Roman, Late-Roman and Early Byzantine town in North-Central Bulgaria: The mammalian fauna from Nicopolis-ad-Istrum. Anthropozoologica 1997, 25–26, 619–630. [Google Scholar]

- Gudea, A. Soldatul Roman în Dacia (106-275 p.Chr.). Studiu de Arheozoologie Privind Creşterea Animalelor şi Regimul Alimentar în Armata Romană; Editura Mega: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Groot, M.; Albarella, U.; Eger, J.; Evans, J. Cattle management in an Iron Age/Roman settlement in the Netherlands: Archaeozoological and stable isotope analisys. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, M. Animals in Ritual and Economy in a Roman Frontier Community. Excavations in Tiel-Passewaaij; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Sturgeon Fish | Teleost Fish |

|---|---|---|

| Halmyris [24,25] | Unidentified Fish | |

| Halmyris (Stanc, unpublished data) | Acipenser sp. | Cyprinus carpio (carp) |

| Silurus glanis (catfish) | ||

| Esox lucius (pike) | ||

| Sacidava (Stanc, unpublished data) | - | Cyprinus carpio (carp) |

| Silurus glanis (catfish) | ||

| Esox lucius (pike) | ||

| Capidava [26] | - | Unidentified Teleosts |

| Dinogetia [27] | - | Cyprinus carpio (carp) |

| Silurus glanis (catfish) | ||

| Esox lucius (pike) | ||

| Aegyssus (Stanc, unpublished data) | Acipenser sp. | Cyprinus carpio (carp) |

| Silurus glanis (catfish) | ||

| Esox lucius (pike) | ||

| Unidentified Teleosts | ||

| Noviodunum [28] | Acipenser sp. | Cyprinus carpio (carp) |

| Silurus glanis (catfish) | ||

| Esox lucius (pike) | ||

| Sander lucioperca (sander) | ||

| Unidentified Teleosts | ||

| Noviodunum [29,30] | Acipenser sp. | Cyprinus carpio (carp) |

| Silurus glanis (catfish) | ||

| Unidentified Teleosts | ||

| Sample | Birds | |

|---|---|---|

| Taxon | NISP | |

| Halmyris [24,25] | Gallus domesticus (chicken) | 50 |

| Anser domesticus (goose) | 5 | |

| Anas plathyrinchos (duck) | 4 | |

| Unidentified birds | 28 | |

| Halmyris (Stanc, unpublished data) | Gallus domesticus (chicken) | 4 |

| Large unidentified bird | 5 | |

| Sacidava (Stanc, unpublished data) | Gallus domesticus (chicken) | 1 |

| Large unidentified bird | 1 | |

| Capidava [26] | Gallus domesticus (chicken) | 2 |

| Large unidentified bird | 1 | |

| Dinogetia [27] | Gallus domesticus (chicken) | 5 |

| Anatidae? (water birds) | 2 | |

| Aegyssus (Stanc, unpublished data) | Gallus domesticus (chicken) | 6 |

| Unidentified bird | 1 | |

| Noviodunum [28] | Gallus domesticus (chicken) | 12 |

| Large unidentified bird | 10 | |

| Unidentified birds | 14 | |

| Noviodunum [29,30] | Gallus domesticus (chicken) | 1 |

| Unidentified birds | 9 | |

| Taxon | Halmyris [24,25] | Halmyris (Unpublished Data) | Sacidava (Unpublished Data) | Capidava [26] | Dinogetia [27] | Aegyssus (Unpublished Data) | Noviodunum [29,30] | Noviodunum [28] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NISP | % | NISP | % | NISP | % | NISP | % | NISP | % | NISP | % | NISP | % | NISP | % | |

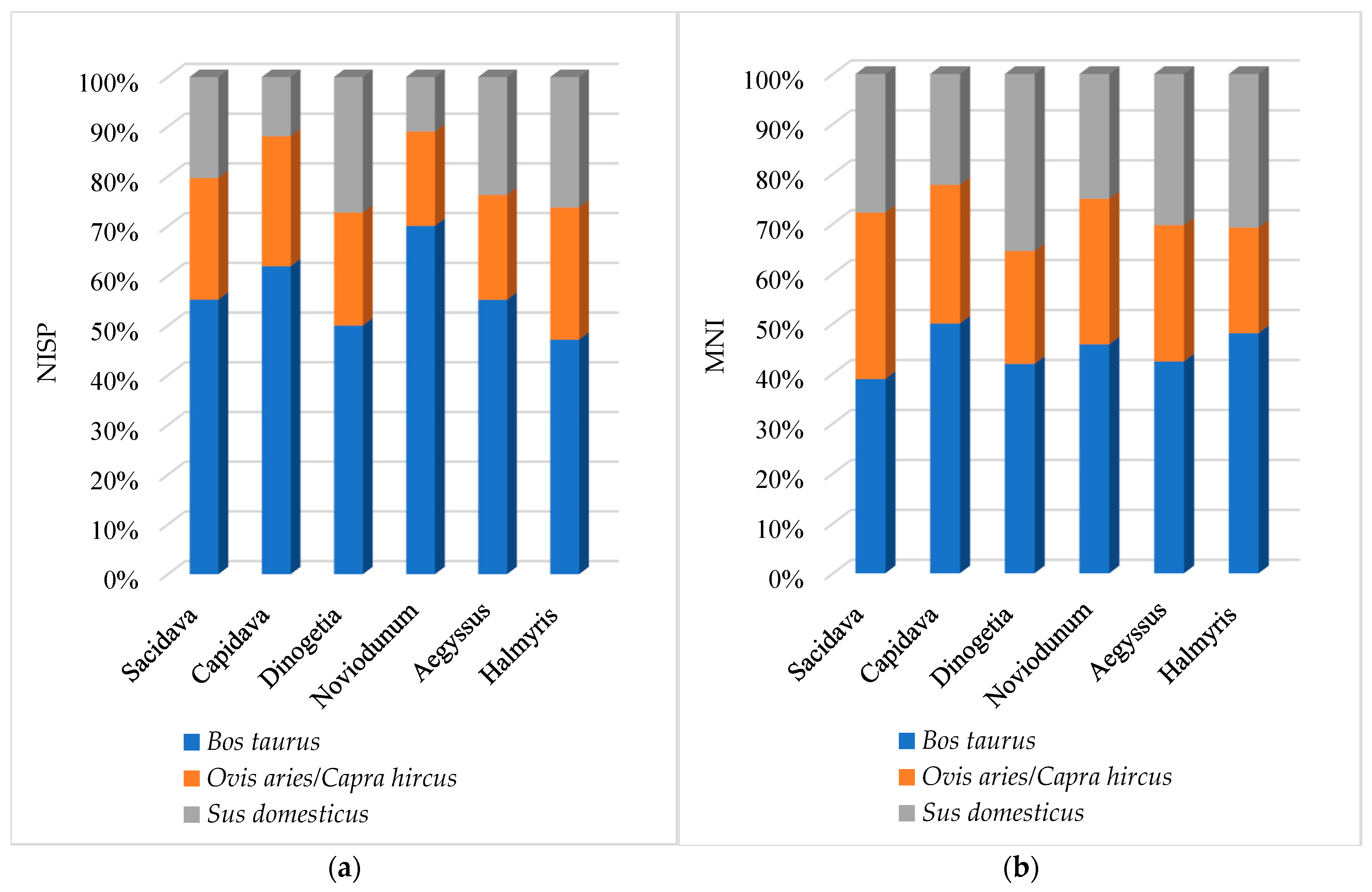

| Bos taurus (cattle) | 685 | 24.0 | 929 | 54.1 | 174 | 46.7 | 83 | 51.6 | 44 | 41.5 | 435 | 47.5 | 132 | 56.9 | 474 | 60.2 |

| Ovis aries/Capra hircus (sheep/goat) | 642 | 22.5 | 268 | 15.6 | 77 | 20.6 | 35 | 21.7 | 20 | 18.9 | 166 | 18.1 | 52 | 22.4 | 112 | 14.2 |

| Sus domesticus (pig) | 708 | 24.9 | 190 | 11.1 | 64 | 17.2 | 16 | 9.9 | 24 | 22.7 | 187 | 20.4 | 38 | 16.4 | 57 | 7.2 |

| Equus caballus (horse) | 127 | 4.5 | 63 | 3.7 | 10 | 2.7 | 5 | 3.1 | 3 | 2.8 | 28 | 3.1 | 1 | 0.4 | 56 | 7.1 |

| Equus asinus (donkey) | 16 | 0.6 | 10 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Canis familiaris (dog) | 58 | 2.0 | 46 | 2.7 | 6 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.2 | 4 | 3.8 | 6 | 0.7 | 4 | 1.7 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Felis domesticus (cat) | 8 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

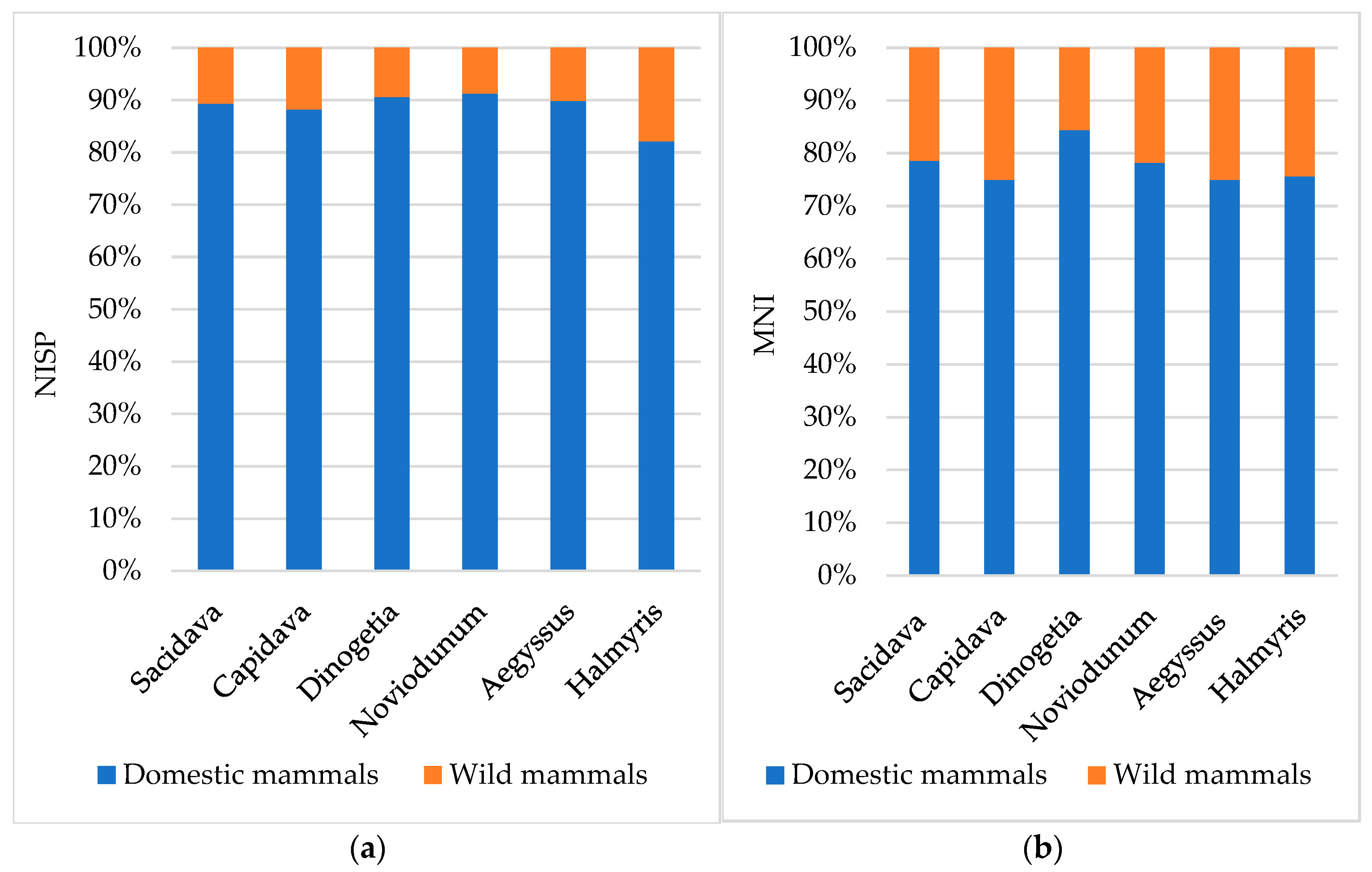

| Total domestic mammals | 2244 | 78.8 | 1506 | 87.7 | 333 | 89.3 | 142 | 88.2 | 96 | 90.6 | 823 | 89.9 | 227 | 97.8 | 704 | 89.3 |

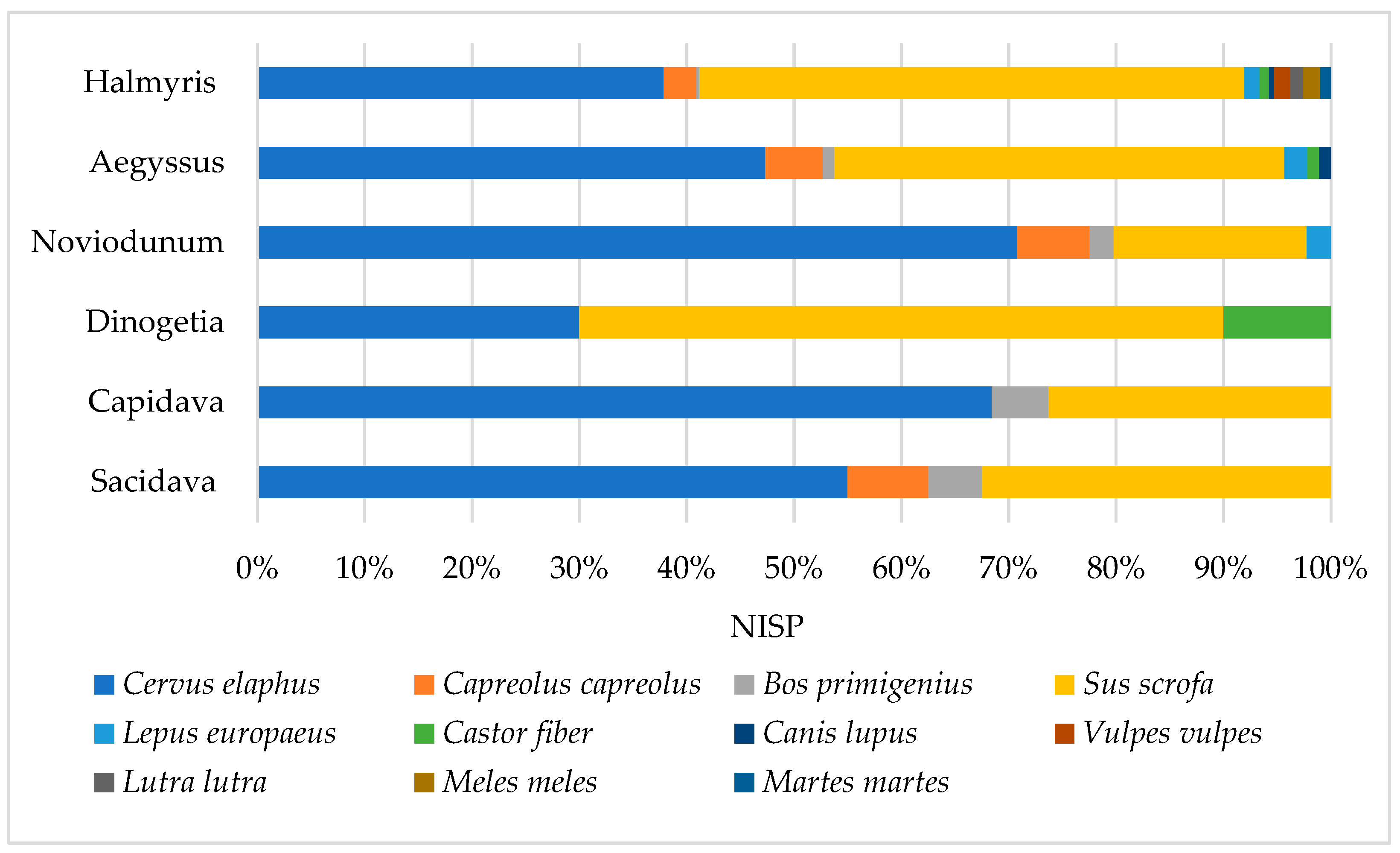

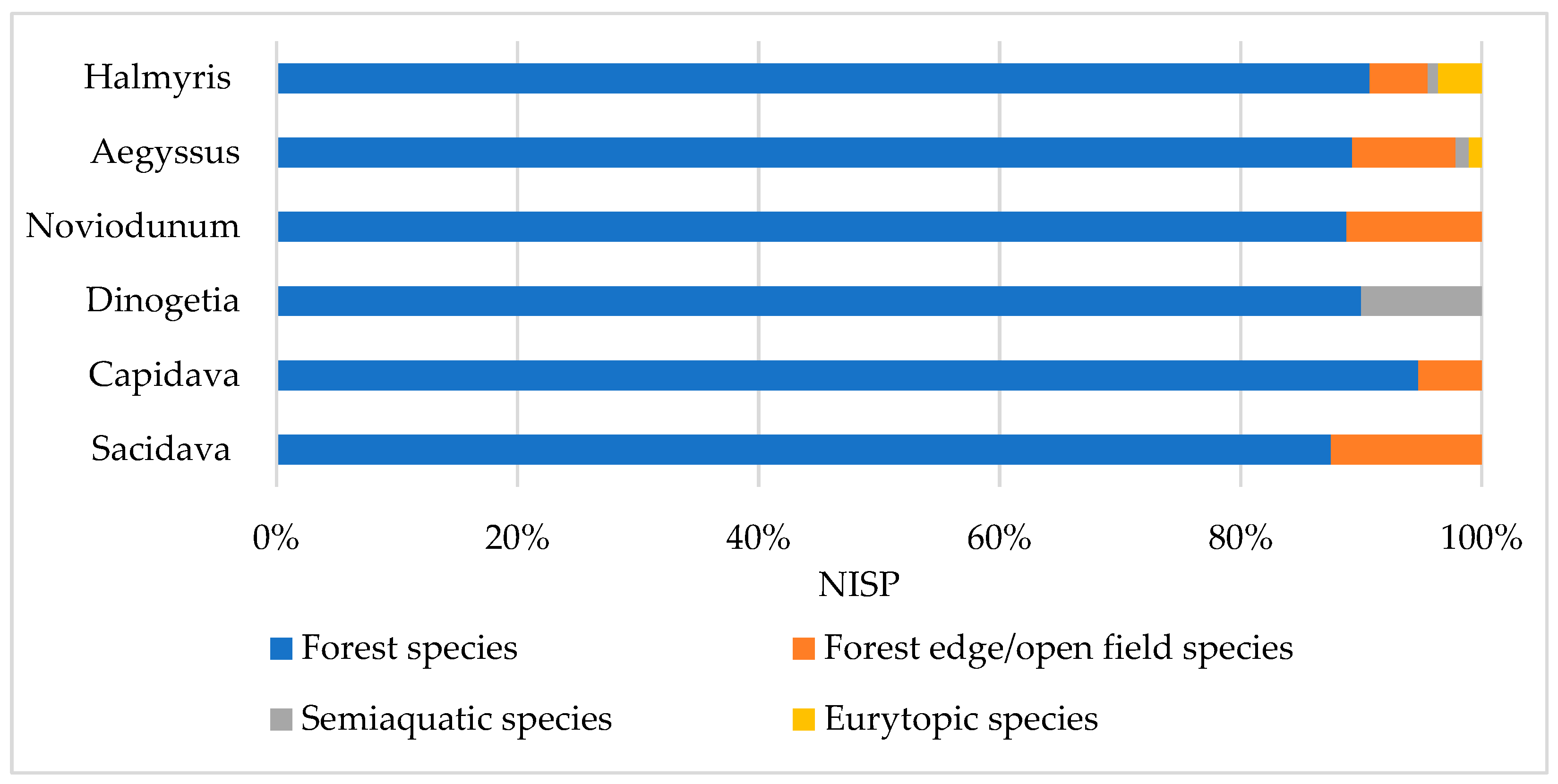

| Cervus elaphus (red deer) | 209 | 7.3 | 100 | 5.8 | 22 | 5.9 | 13 | 8.1 | 3 | 2.8 | 44 | 4.8 | 2 | 0.9 | 61 | 7.7 |

| Capreolus capreolus (roe deer) | 16 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Bos primigenius (auroch) | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 |

| Sus scrofa (wild boar) | 330 | 11.6 | 84 | 4.9 | 13 | 3.5 | 5 | 3.1 | 6 | 5.7 | 39 | 4.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 15 | 1.9 |

| Lepus europaeus (hare) | 10 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Castor fiber (beaver) | 5 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Canis lupus (wolf) | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Vulpes vulpes (fox) | 11 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Lutra lutra (Eurasian otter) | 10 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Meles meles (badger) | 5 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Martes martes (pine marten) | 8 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total wild mammals | 605 | 21.2 | 211 | 12.3 | 40 | 10.7 | 19 | 11.8 | 10 | 9.4 | 93 | 10.2 | 5 | 2.2 | 84 | 10.7 |

| Total identified mammals | 2849 | 100.0 | 1717 | 100.0 | 373 | 100.0 | 161 | 100.0 | 106 | 100.0 | 916 | 100.0 | 232 | 100.0 | 788 | 100.0 |

| Unidentified mammals | 608 | 297 | 65 | 0 | 23 | 197 | 118 | 344 | ||||||||

| Total mammals | 3457 | - | 2014 | - | 438 | - | 161 | - | 129 | - | 1113 | - | 350 | - | 1132 | - |

| Taxon | Halmyris * (Unpublished Data) | Sacidava (Unpublished Data) | Capidava [26] | Dinogetia [27] | Aegyssus (Unpublished Data) | Noviodunum [29,30] | Noviodunum [28] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNI | % | MNI | % | MNI | % | MNI | % | MNI | % | MNI | % | MNI | % | |

| Bos taurus (cattle) | 25 | 30.5 | 7 | 25.0 | 9 | 28.1 | 13 | 28.9 | 14 | 26.9 | 7 | 33.3 | 15 | 31.3 |

| Ovis aries/Capra hircus (sheep/goat) | 11 | 13.4 | 6 | 21.4 | 5 | 15.6 | 7 | 15.6 | 9 | 17.3 | 4 | 19.1 | 10 | 20.8 |

| Sus domesticus (pig) | 16 | 19.5 | 5 | 17.9 | 4 | 12.5 | 11 | 24.4 | 10 | 19.2 | 4 | 19.1 | 8 | 16.7 |

| Equus caballus (horse) | 4 | 4.9 | 2 | 7.1 | 3 | 9.4 | 3 | 6.7 | 3 | 5.8 | 1 | 4.8 | 3 | 6.3 |

| Equus asinus (donkey) | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 3.6 | 1 | 3.1 | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Canis familiaris (dog) | 4 | 4.9 | 1 | 3.6 | 2 | 6.3 | 3 | 6.7 | 2 | 3.9 | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 2.1 |

| Total domestic mammals | 62 | 75.6 | 22 | 78.6 | 24 | 75.0 | 38 | 84.4 | 39 | 75.0 | 17 | 81.0 | 37 | 77.1 |

| Cervus elaphus (red deer) | 6 | 7.3 | 2 | 7.1 | 4 | 12.5 | 2 | 4.4 | 4 | 7.7 | 1 | 4.8 | 4 | 8.3 |

| Capreolus capreolus (roe deer) | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 4.8 | 2 | 4.2 |

| Bos primigenius (auroch) | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 3.6 | 1 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.1 |

| Sus scrofa (wild boar) | 5 | 6.1 | 2 | 7.1 | 3 | 9.4 | 4 | 8.9 | 4 | 7.7 | 1 | 4.8 | 3 | 6.3 |

| Lepus europaeus (hare) | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 2.1 |

| Castor fiber (beaver) | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Canis lupus (wolf) | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Vulpes vulpes (fox) | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Meles meles (badger) | 2 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total wild mammals | 20 | 24.4 | 6 | 21.4 | 8 | 25.0 | 7 | 15.6 | 13 | 25.0 | 4 | 19.1 | 11 | 22.9 |

| Total identified mammals | 82 | 100.0 | 28 | 100.0 | 32 | 100.0 | 45 | 100.0 | 52 | 100.0 | 21 | 100.0 | 48 | 100.0 |

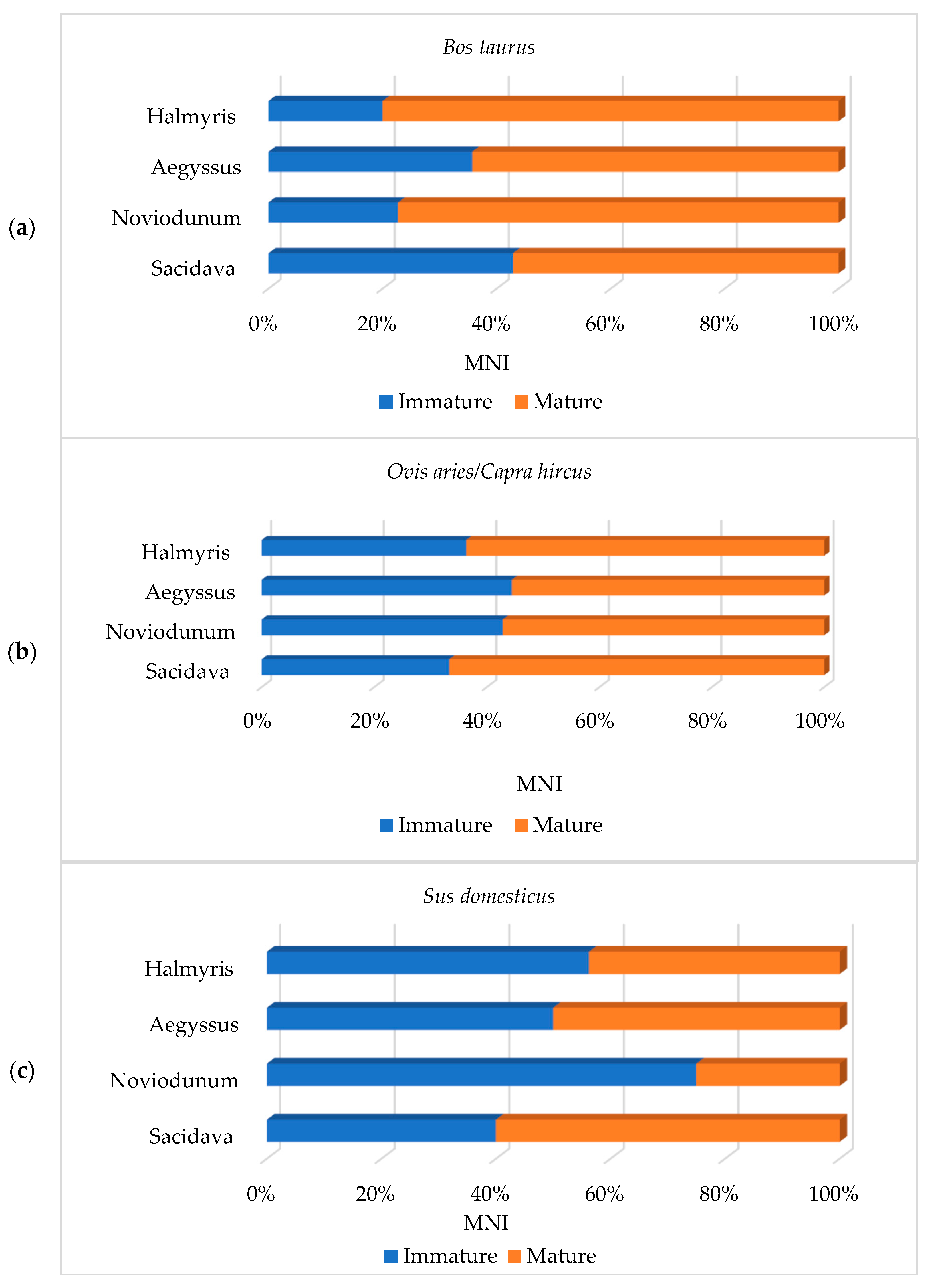

| Samples | Bos taurus | Ovis aries/Capra hircus | Sus domesticus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immature (under 2.5 Years Old) MNI | Mature (over 2.5 Years Old) MNI | Immature (under 2 Years Old) MNI | Mature (over 2 Years Old) MNI | Immature (under 2 Years Old) MNI | Mature (over 2 Years Old) MNI | |

| Aegyssus (unpublished) | 5 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Noviodunum [28,29] | 5 | 17 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 3 |

| Sacidava (unpublished) | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Halmyris (unpublished) | 5 | 20 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stanc, S.M.; Nuțu, G.; Mototolea, A.C.; Bejenaru, L. Daily Life in the Limesgebiet: Archaeozoological Evidence on Animal Resource Exploitation in Lower Danubian Sites of 2nd–6th Centuries AD. Diversity 2022, 14, 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080640

Stanc SM, Nuțu G, Mototolea AC, Bejenaru L. Daily Life in the Limesgebiet: Archaeozoological Evidence on Animal Resource Exploitation in Lower Danubian Sites of 2nd–6th Centuries AD. Diversity. 2022; 14(8):640. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080640

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanc, Simina Margareta, George Nuțu, Aurel Constantin Mototolea, and Luminița Bejenaru. 2022. "Daily Life in the Limesgebiet: Archaeozoological Evidence on Animal Resource Exploitation in Lower Danubian Sites of 2nd–6th Centuries AD" Diversity 14, no. 8: 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080640

APA StyleStanc, S. M., Nuțu, G., Mototolea, A. C., & Bejenaru, L. (2022). Daily Life in the Limesgebiet: Archaeozoological Evidence on Animal Resource Exploitation in Lower Danubian Sites of 2nd–6th Centuries AD. Diversity, 14(8), 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080640