The Relationship between Population Density and Body Size of the Giant Mountain Crab Indochinamon bhumibol (Naiyanetr, 2001), an Endangered Species of Freshwater Crab from Northeastern Thailand (Potamoidea: Potamidae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

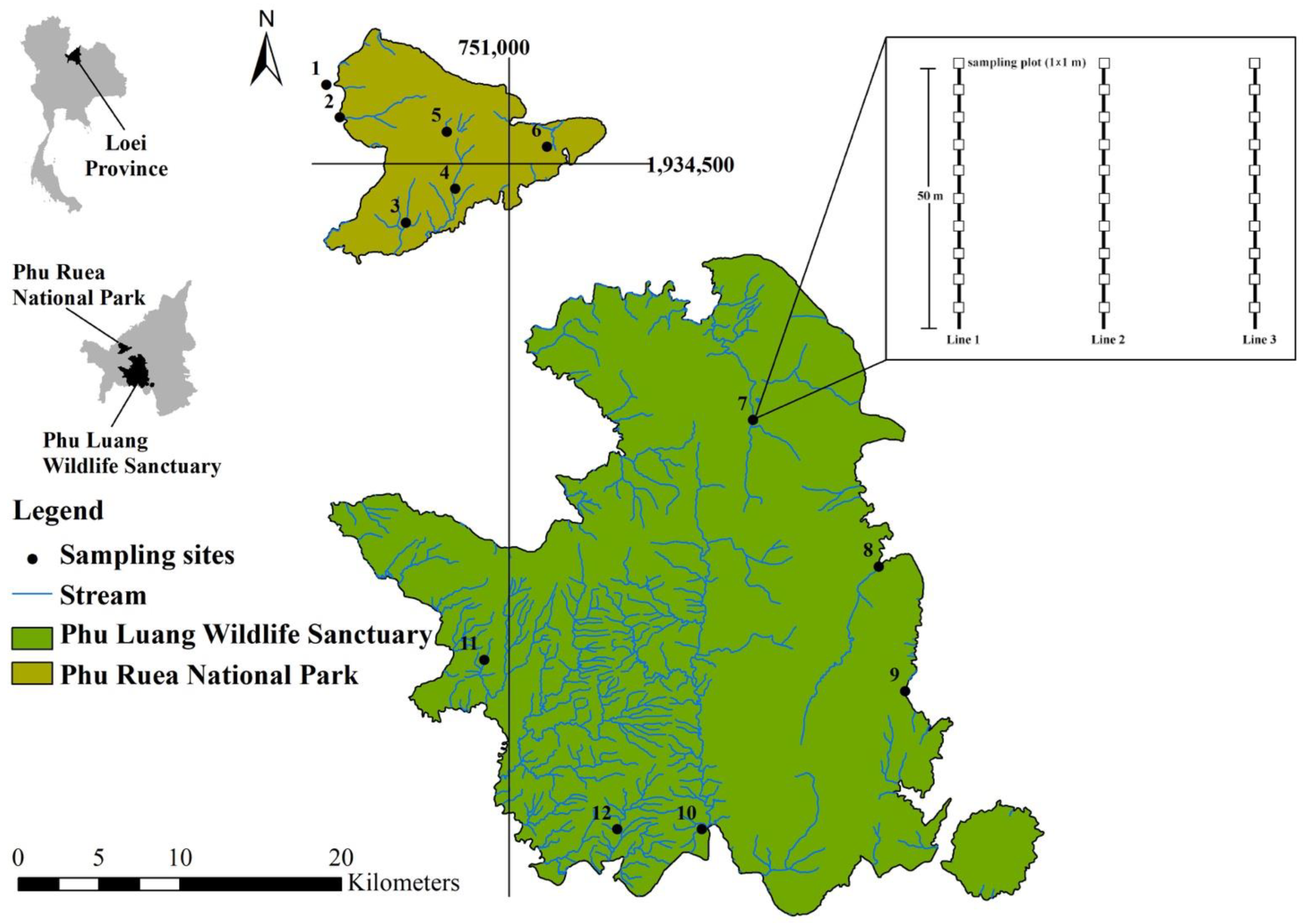

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Sampling and Body Size Measurement

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

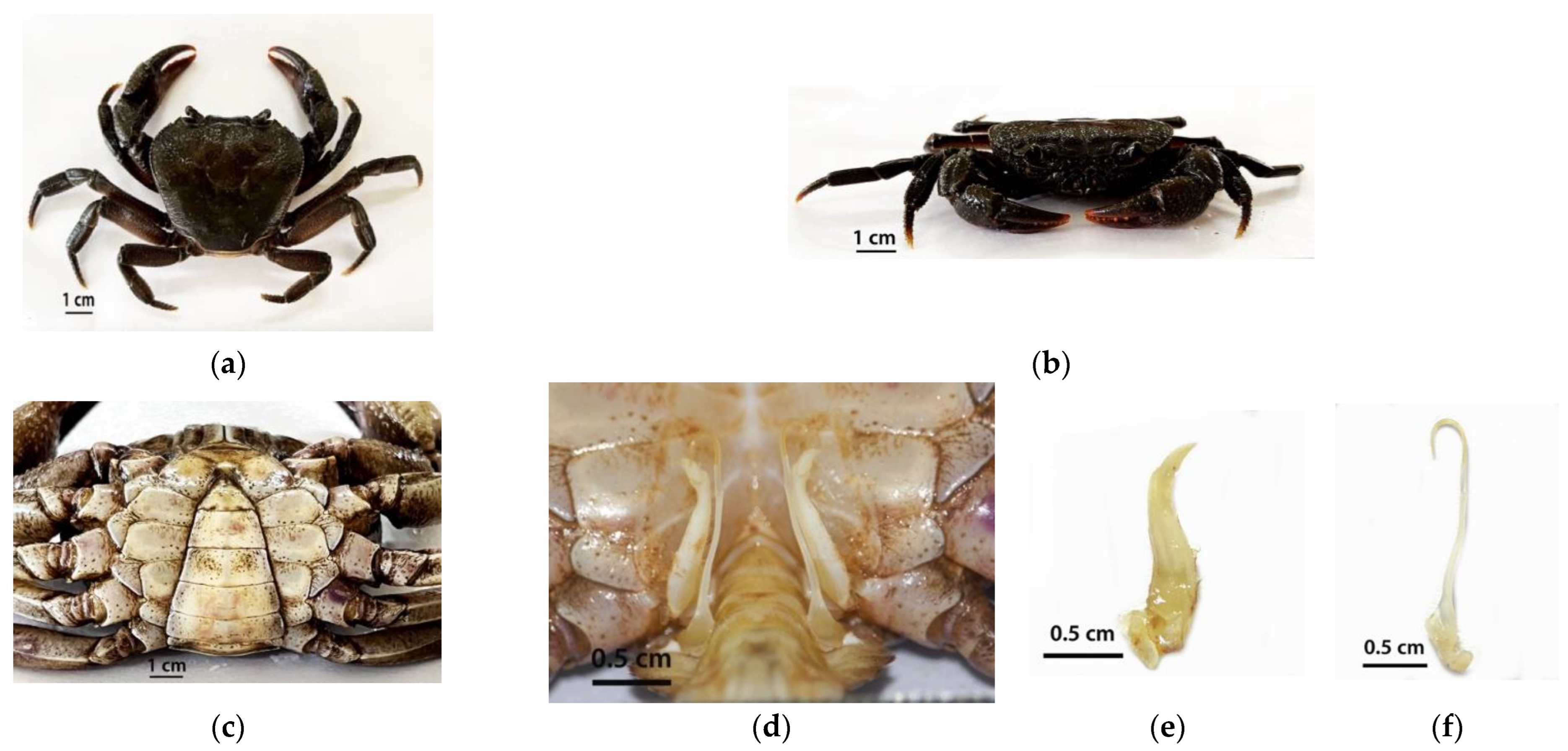

3.1. Morphology

3.2. Abundance, Body Size and Sex Ratio

3.3. Population Size and Density

3.4. Relationship between Population Density and Body Size

4. Discussion

4.1. Abundance and Body Size

4.2. Population Size and Density

4.3. Relationship between Population Density and Body Size

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cumberlidge, N.; Ng, P.K.L.; Yeo, D.C.J.; Magalhaes, C.; Campos, M.R.; Alvarez, F.; Naruse, T.; Daniels, S.R.; Esser, L.J.; Attipoe, F.Y.K.; et al. Freshwater crabs and the biodiversity crisis: Importance, threats, status, and conservation challenges. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lheknim, V.; Leelawathanagoon, P. A new record freshwater crab Phricotelphusa callianira (De Man, 1887) (Decapoda: Brachyura: Gecarcinucidae) from Thailand. J. Threat. Taxa 2009, 1, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.K.L.; Naiyanetr, P. New and recently described freshwater crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamidae, Gecarcinucidae and Parathelphusidae) from Thailand. Zool. Verhandelingen 1993, 284, 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- Naiyanetr, P. Potamon bhumibol N. Sp., A new giant Freshwater crab from Thailand (Decapoda, Brachyura, Potamidae). Crustaceana 2001, 74, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthamrit, W.; Thaewnon-ngiw, B. Morphometry of mountain crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamidae) from Phetchabun Mountains Thailand. Interdiscip. Res. Rev. 2020, 15, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, L.; Cumberlidge, N. Indochinamon bhumibol. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008; IUCN UK Office: Cambridge, UK, 2008; e.T135035A4058369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, D.C.J.; Ng, P.K.L.; Cumberlidge, N.; Magalhaes, C.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Campos, M.R. Global diversity of crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 2008, 595, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, D.C.J.; Naiyanetr, P. A new genus of freshwater crab (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamidae) from Thailand, with a description of a new species. J. Nat. Hist. 2000, 34, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supajantra, S. Taxonomy of Freshwater Crabs in The North-Eastern Thailand; Chulalongkorn University: Bangkok, Thailand, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Thawarorit, K.; Sangpradub, N.; Morse, J.C. Five new species of the genus Cheumatopsyche (Trichoptera: Hydropsychidae) from the Phetchabun Mountains, Thailand. Zootaxa 2013, 3613, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buatip, S.; Yeesin, P.; Samaae, S. Some aspects of the biology of 5 freshwater crabs in lower Southern Part of Thailand. Burapha Sci. J. 2018, 23, 431–447. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, K.W.J.; Ng, D.J.J.; Zeng, Y.; Yeo, D.C.J. Habitat characteristics of tropical rainforest freshwater crabs (Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamidae, Gecarcinucidae) in Singapore. J. Crust. Biol. 2015, 35, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuensri, C. Freshwater Crabs of Thailand. J. Fish. Environ. 1974, 7, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Naruse, T.; Chia, J.E.; Zhou, X. Biodiversity surveys reveal eight new species of freshwater crabs (Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamidae) from Yunnan Province, China. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinang, J.; Das, I.; Ng, P. Ecological Characteristics of the Freshwater Crab, Isolapotamon bauense in One of Wallace’s Collecting Sites. In Naturalists, Explorers and Field Scientists in South-East Asia and Australasia; Das, I., Tuen, A., Eds.; Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo Carvalho, D.; Collins, P.A.; de Bonis, C.J. Predation ability of freshwater crabs: Age and prey-specific differences in Trichodactylus borellianus (Brachyura: Trichodactylidae). J. Freshw. Ecol. 2013, 28, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilada, R.; Driscoll, J.G. Age determination in crustaceans: A review. Hydrobiologia 2017, 799, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pal, N. Estimation of a population size through capture-mark-recapture method: A comparison of various point and interval estimators. J. Stat. Comput Simul. 2010, 80, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, J.J.P.R.d.; Silva, J.R.F.; Rezende, C.F.; Martins, R.P.; Ferreira, T.O.; Souza, L.P. Population biology of the crab Goniopsis cruentata: Variation in body size, sexual maturity, and population density. Ani. Biol. 2014, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, G.L.; Souza, L.S.; Silva, S.L.R.; Alves, D.F.R.; Negreiros-Fransozo, L.M. Population structure of the red mangrove crab, Goniopsis cruentata (Decapoda: Grapsidae) under different fishery impacts: Implications for resource management. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2015, 63, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dalu, T.; Sachikoney, M.T.B.; Alexander, M.E.; Dube, T.; Froneman, W.P.; Manungo, K.I.; Bepe, O.; Wasserman, R.J. Ecological assessment of two species of Potamonautid freshwater crabs from the eastern highlands of Zimbabwe with implications for their conservation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macia, A.; Quincardete, I.; Paula, J. A comparison of alternative methods for estimating population density of the fiddler crab Uca annulipes at Saco Mangrove, Inhaca Island (Mozambique). Hydrobiologia 2001, 449, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, G.; Bagarinao, T.; Yong, A.S.K.; Chen, C.Y.; Noor, S.N.M.; Lim, L.S. Low pH affects survival, growth, size distribution, and carapace quality of the postlarvae and early juveniles of the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii de Man. Ocean Sci. J. 2015, 50, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davanso, T.M.; Taddei, F.G.; Simões, S.M.; Fransozo, A.; Costa, R.C.D. Population dynamics of the freshwater crab Dilocarcinus pagei in tropical waters in Southeastern Brazil. J. Crust. Biol. 2013, 33, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, Z.S.; Neri, J.B.; Cañete, R.M.P.; Metillo, E.B. Body Size, Habitat, and Diet of Freshwater Crabs Isolapotamon mindanaoense and Sundathelphusa miguelito (Crustacea: Brachyura) in the Municipality of Lake Sebu, South Cotabato, Philippines. Sci. Diliman 2020, 32, 68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, D.E.C.; Arce, U.E.; Viveros-Guardado, D.A. Population density, microhabitat use, and size characteristics of Pseudothelphusa dugesi, a threatened species of freshwater crab from Mexico (Brachyura: Pseudothelphusidae). Invertebr. Biol. 2020, 139, e12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, F.; Micheli, F. Relative growth and population structure of the freshwater crab, Potamon potamios palestinensis in the Dead Sea area (Israel). Israel J. Zool. 1989, 36, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, M.; Magana, A.M.; Lancaster, J.; Mathooko, J.M. Aseasonality in the abundance and life history of an ecologically dominant freshwater crab in the Rift Valley, Kenya. Freshw. Biol. 2007, 52, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumberlidge, N.; Ng, P.K.L.; Yeo, D.C.J.; Naruse, T.; Meyer, K.S.; Esser, L.J. Diversity, endemism and conservation of the freshwater crabs of China (Brachyura: Potamidae and Gecarcinucidae). Integrat. Zool. 2011, 6, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environmental Variables | Study Site | Sand | Silt | Clay | Mean ± Sd | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil texture (%) | PL | 50–70 | 0 | 15–20 | ||||

| PR | 50–70 | 0 | 15–20 | |||||

| Depth of water (m) | PL | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 47 | 1.78 | 0.085 | |||

| PR | 0.5 ± 0.3 | |||||||

| Stream width (m) | PL | 9.7 ± 6.7 | 47 | 1.81 | 0.076 | |||

| PR | 6.8 ± 3.8 | |||||||

| Water temperature (°C) | PL | 17.9 ± 3.6 | 47 | −0.09 | 0.932 | |||

| PR | 18.0 ± 3.1 | |||||||

| pH | PL | 7.6 ± 1.0 | 47 | 3.16 | 0.003 | |||

| PR | 6.8 ± 0.6 | |||||||

| Air temperature (°C) | PL | 26.7 ± 1.4 | 47 | −0.5 | 0.623 | |||

| PR | 26.9 ± 1.5 |

| Month | PL | PR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Unk | Sex Ratio | Male | Female | Unk | Sex Ratio | |

| Feb 2018 | 43 | 25 | 5 | 1:0.6 | 19 | 10 | 1 | 1:0.7 |

| Mar 2018 | 31 | 0 | 11 | N/A | 19 | 8 | 8 | 1:0.7 |

| Apr 2018 | 24 | 15 | 3 | 1:0.6 | 11 | 8 | 0 | 1:0.6 |

| May 2018 | 9 | 14 | 3 | 1:0.4 | 8 | 17 | 16 | 1:0.3 |

| Jun 2018 | 38 | 30 | 11 | 1:0.6 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 1:0.6 |

| Jul 2018 | 27 | 44 | 14 | 1:0.4 | 15 | 10 | 12 | 1:0.6 |

| Aug 2018 | 39 | 26 | 16 | 1:0.6 | 18 | 13 | 6 | 1:0.6 |

| Sep 2018 | 37 | 14 | 4 | 1:0.7 | 22 | 19 | 16 | 1:0.5 |

| Oct 2018 | 89 | 125 | 26 | 1:0.4 | 11 | 16 | 4 | 1:0.4 |

| Nov 2018 | 19 | 11 | 0 | 1:0.6 | 29 | 24 | 29 | 1:0.6 |

| Dec 2018 | 20 | 9 | 6 | 1:0.7 | 61 | 53 | 32 | 1:0.5 |

| Jan 2019 | 50 | 41 | 0 | 1:0.6 | 22 | 16 | 4 | 1:0.6 |

| PA | Sub-Sites | N | Mean ± Sd | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | Carapace (mm) | ||||||||||||

| Width | Length | ||||||||||||

| Total | Ad | Ju | Total | Ad | Ju | Total | Ad | Ju | Total | Ad | Ju | ||

| PL | HNS | 125 | 120 | 5 | 49.4 ± 19.6 de | 50.9 ± 18.5 cd | 13 ± 9.7 a | 46.9 ± 7.7 d | 47.7 ± 6.8 de | 28.8 ± 7.1 a | 37.4 ± 6.5 cd | 38.0 ± 5.8 cd | 23.2 ± 5.7 a |

| HNT | 81 | 73 | 8 | 37.9 ± 17.5 bc | 40.8 ± 15.9 bc | 11.8 ± 5.3 a | 43.3 ± 7.1 cd | 44.6 ± 6.1 cd | 31.1 ± 2.7 ab | 34.6 ± 5.8 bc | 35.7 ± 5 bc | 24.4 ± 2 ab | |

| HNK2 | 243 | 214 | 29 | 31.7 ± 15.4 ab | 34.5 ± 14.1 ab | 10.5 ± 3.6 a | 39 ± 7.9 bc | 40.7 ± 6.7 bc | 27.3 ± 5.7 a | 31.5 ± 5.9 b | 32.8 ± 4.8 b | 22.1 ± 4.5 a | |

| HNL | 51 | 43 | 8 | 47.6 ± 29.4 cde | 54.8 ± 26.2 de | 8.7 ± 2.3 a | 44 ± 12.6 cd | 47.6 ± 10.2 de | 24.7 ± 2.3 a | 35.7 ± 10.2 cd | 38.5 ± 8.5 cd | 20.4 ± 1.5 a | |

| HS | 92 | 92 | 0 | 51.3 ± 24.5 e | 51.3 ± 24.5 cd | 0 N/A | 47.3 ± 8.6 d | 47.3 ± 8.6 d | 0 N/A | 38.7 ± 7.4 d | 38.7 ± 7.4 cd | 0 N/A | |

| HPB | 152 | 136 | 16 | 31.6 ± 20.4 ab | 33.3 ± 20.7 ab | 17.5 ± 10.6 ab | 36.6 ± 10 ab | 38.1 ± 9.2 ab | 24.4 ± 9.5 a | 30.9 ± 8.5 b | 32.1 ± 8 ab | 21 ± 6.9 a | |

| PR | HTi | 137 | 105 | 32 | 21.4 ± 10.5 a | 24.8 ± 9.4 a | 10.4 ± 5.5 a | 33 ± 7.4 a | 35.4 ± 5.8 a | 24.9 ± 6.5 a | 26.8 ± 5.2 a | 28.5 ± 3.9 a | 21.1 ± 4.9 a |

| HK | 55 | 35 | 20 | 49.9 ± 27.9 de | 65.2 ± 22.9 e | 22.9 ± 8.5 b | 47 ± 10.6 d | 52.1 ± 8.6 e | 38 ± 7.5 b | 38.4 ± 8.6 cd | 42.8 ± 6.8 e | 30.8 ± 5.8 b | |

| HSK | 72 | 59 | 13 | 44.7 ± 26 cde | 52.3 ± 22.3 d | 10 a | 44.8 ± 12.8 d | 49.1 ± 9.7 de | 25.1 ± 2.8 a | 36.5 ± 11.9 cd | 40.1 ± 10 de | 20.2 ± 1.6 a | |

| HP | 66 | 46 | 20 | 40.3 ± 26 bcd | 51.3 ± 23.9 cd | 15 ± 5.1 ab | 42.7 ± 10.5 cd | 47.8 ± 8.2 de | 31 ± 2.9 ab | 34.6 ± 8.4 bc | 38.6 ± 6.9 cd | 25.5 ± 2.4 ab | |

| HTo | 45 | 41 | 4 | 49.7 ± 29 de | 53.6 ± 27.5 d | 10 a | 46.8 ± 11.9 d | 48.4 ± 11.3 de | 30.7 ± 1.4 ab | 37.9 ± 9.8 cd | 39.3 ± 9.2 cde | 24.1 ± 1.1 ab | |

| HNK1 | 61 | 54 | 7 | 50.8 ± 19 de | 55.1 ± 15.4 de | 17.1 ± 4.8 ab | 45.8 ± 9.7 d | 48.2 ± 7.3 de | 27.5 ± 4.7 a | 39.1 ± 7.2 d | 40.9 ± 5.4 de | 25.8 ± 5.1 ab | |

| df | 1179 | 1017 | 161 | 1179 | 1017 | 161 | 1179 | 1017 | 161 | ||||

| F | 24.8 | 30.1 | 8.3 | 28.3 | 34.8 | 8.2 | 27.5 | 33.5 | 8.2 | ||||

| p | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | ||||

| PA | Sub-Sites | N | Mean ± Sd | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | Carapace (mm) | ||||||||||||

| Width | Length | ||||||||||||

| Total | Ad | Ju | Total | Ad | Ju | Total | Ad | Ju | Total | Ad | Ju | ||

| PL | HNS | 78 | 74 | 4 | 50.8 ± 22 cde | 52.8 ± 20.7 cd | 13.7 ± 11 ab | 47.1 ± 8.5 cd | 48.1 ± 7.3 cde | 28.2 ± 8.1 ab | 37.4 ± 7.1 cde | 38.2 ± 6.2 cde | 22.8 ± 6.5 ab |

| HNT | 67 | 60 | 7 | 39.1 ± 18.2 bcd | 42.3 ± 16.5 bc | 12.1 ± 5.6 ab | 43.8 ± 7.3 cd | 45.2 ± 6.3 cd | 31.5 ± 2.6 ab | 35 ± 6.0 bcde | 36.2 ± 5.1 bcd | 24.8 ± 1.9 ab | |

| HNK2 | 111 | 93 | 18 | 34.5 ± 17.9 ab | 39.1 ± 15.9 abc | 11.1 ± 4.3 ab | 40.2 ± 9.3 bc | 42.6 ± 7.6 bc | 27.7 ± 6.7 ab | 32.1 ± 6.9 abc | 34 ± 5.5 abc | 22.5 ± 5.3 ab | |

| HNL | 26 | 21 | 5 | 55.9 ± 33.8 e | 67.1 ± 27.4 de | 9 ± 2.2 a | 46.8 ± 14.2 cd | 52 ± 10.2 de | 24.9 ± 2.1 a | 38.1 ± 10.9 de | 42.2 ± 7.5 ef | 20.8 ± 1.4 a | |

| HS | 55 | 55 | 0 | 54.5 ± 27.3 de | 54.5 ± 27.3 cd | 0 N/A | 48.2 ± 9.8 d | 48.2 ± 9.8 cde | 0 N/A | 39.1 ± 7.4 e | 39.1 ± 7.4 cde | 0 N/A | |

| HPB | 75 | 65 | 10 | 32.3 ± 22.4 ab | 34.7 ± 22.7 ab | 16.5 ± 10.8 ab | 36.2 ± 11.5 ab | 38.3 ± 10.2 ab | 22.6 ± 10.5 a | 29.7 ± 8.9 ab | 31.3 ± 8.1 ab | 19.6 ± 7.5 a | |

| PR | HTi | 73 | 54 | 19 | 21.5 ± 10.5 a | 25.7 ± 8.3 a | 9.7 ± 5.8 ab | 32.8 ± 8.1 a | 35.7 ± 6.7 a | 24.4 ± 5.4 a | 26.5 ± 5.6 a | 28.9 ± 3.7 a | 19.9 ± 5 a |

| HK | 33 | 19 | 14 | 50.8 ± 32.2 cde | 72.6 ± 24.9 e | 21.3 ± 8.4 b | 46.8 ± 11.5 cd | 54.6 ± 8.7 e | 36.2 ± 3.2 b | 38.3 ± 9.5 e | 44.9 ± 6.9 f | 29.5 ± 3.1 b | |

| HSK | 34 | 26 | 8 | 43.2 ± 28.2 bcde | 53.5 ± 24.3 cd | 10 a b | 44.1 ± 14.4 cd | 50.1 ± 10.8 de | 24.9 ± 3.2 a | 36.6 ± 14.4 cde | 41.5 ± 12.8 def | 20.6 ± 1.7 a | |

| HP | 39 | 24 | 15 | 35.3 ± 23.6 abc | 47.5 ± 22.5 bc | 16 ± 5 ab | 40.3 ± 9.1 bc | 45.5 ± 7.7 cd | 31.8 ± 2.4 ab | 32.4 ± 7.2 bcd | 36.4 ± 6.2 bcd | 25.9 ± 2.2 ab | |

| HTo | 22 | 19 | 3 | 45.4 ± 32.9 bcde | 51 ± 31.9 bcd | 10 ab | 44.6 ± 13.3 cd | 46.9 ± 13 cd | 30.4 ± 1.6 ab | 35.5 ± 10.6 bcde | 37.3 ± 10.3 cde | 24 ± 1.3 ab | |

| HNK1 | 36 | 33 | 3 | 50.9 ± 18 cde | 54.4 ± 14.6 cd | 13.3 ± 5.7 ab | 46.7 ± 10 cd | 48.7 ± 7.4 cde | 23.8 ± 5.7 a | 39.7 ± 7.4 e | 41.1 ± 5.6 def | 23.5 ± 5.5 ab | |

| df | 648 | 542 | 105 | 648 | 542 | 105 | 648 | 542 | 105 | ||||

| F | 12.4 | 14.9 | 4 | 14.1 | 16.5 | 6.3 | 14.9 | 17.9 | 5.6 | ||||

| p | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | ||||

| PA | Sub-Sites | N | Mean ± Sd | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | Carapace (mm) | ||||||||||||

| Width | Length | ||||||||||||

| Total | Ad | Ju | Total | Ad | Ju | Total | Ad | Ju | Total | Ad | Ju | ||

| PL | HNS | 47 | 46 | 1 | 47 ± 14.8 cde | 47.8 ± 13.9 de | 10 N/A | 46.7 ± 6.4 de | 47 ± 6 cde | 31.1 N/A | 37.3 ± 5.4 cdef | 37.6 ± 5.1 cde | 24.8 N/A |

| HNT | 14 | 13 | 1 | 32.1 ± 12.5 abc | 33.8 ± 11.2 abcd | 10 N/A | 40.9 ± 5.8 bcd | 41.9 ± 4.7 bc | 27.9 N/A | 32.4 ± 4.6 abcd | 33.2 ± 3.6 abc | 21.9 N/A | |

| HNK2 | 132 | 121 | 11 | 29.2 ± 12.4 ab | 31 ± 11.3 ab | 9.5 ± 1.5 ab | 38.2 ± 6.4 abc | 39.3 ± 5.5 ab | 26.7 ± 3.7 a | 31 ± 4.9 ab | 31.8 ± 4 ab | 21.4 ± 2.9 a | |

| HNL | 25 | 22 | 3 | 39 ± 21.3 bcd | 43.1 ± 19.1 bcde | 8.3 ± 2.8 a | 41.1 ± 10.1 bcd | 43.3 ± 8.4 bcd | 24.5 ± 3.3 a | 33.2 ± 9 bcde | 35.1 ± 8 bcd | 19.8 ± 1.6 a | |

| HS | 37 | 37 | 0 | 46.4 ± 19.1 cde | 46.4 ± 19.1 cde | 0 N/A | 46.1 ± 6.2 de | 46 ± 6.2 cde | 0 N/A | 38 ± 7.4 def | 38 ± 7.4 cde | 0 N/A | |

| HPB | 77 | 71 | 6 | 31 ± 18.4 ab | 32 ± 18.6 abc | 19.1 ± 11.1 bc | 37 ± 8.7 ab | 37.8 ± 8.3 ab | 27.5 ± 7.4 a | 32 ± 8.1 abc | 32.8 ± 8 abc | 23.4 ± 4.6 a | |

| PR | HTi | 64 | 51 | 13 | 21.4 ± 10.7 a | 23.9 ± 10.4 a | 11.5 ± 5.1 ab | 33.1 ± 6.6 a | 35 ± 4.7 a | 25.7 ± 8.1 a | 27 ± 4.7 a | 28.1 ± 4.1 a | 22.9 ± 4.5 a |

| HK | 22 | 16 | 6 | 48.6 ± 20.5 de | 56.8 ± 17.4 e | 26.6 ± 8.1 c | 47.2 ± 9.5 de | 49.2 ± 7.7 de | 42 ± 12.6 b | 38.6 ± 7.5 ef | 40.4 ± 5.9 de | 33.6 ± 9.4 a | |

| HSK | 38 | 33 | 5 | 46 ± 24.2 cde | 51.5 ± 21 e | 10 ab | 45.3 ± 11.4 de | 48.3 ± 8.9 de | 25.4 ± 2.3 a | 36.5 ± 9.3 bcdef | 39.1 ± 7 de | 19.6 ± 1.4 a | |

| HP | 27 | 22 | 5 | 47.4 ± 28.5 de | 55.4 ± 25.2 e | 12 ± 4.4 ab | 46.2 ± 11.5 de | 50.2 ± 8.3 e | 28.3 ± 2.8 a | 37.8 ± 9.2 cdef | 40.9 ± 7 e | 24 ± 2.9 a | |

| HTo | 23 | 22 | 1 | 53.9 ± 24.9 e | 55.9 ± 23.6 e | 10 N/A | 48.8 ± 10.3 e | 49.6 ± 9.8 e | 31.6 N/A | 40.2 ± 8.6 f | 41 ± 8.1 e | 24.4 N/A | |

| HNK1 | 25 | 11 | 4 | 50.6 ± 20.5 de | 56.4 ± 16.8 e | 20 bc | 44.6 ± 9.2 cde | 47.3 ± 7.3 cde | 30.2 ± 0.2 ab | 38.4 ± 7 ef | 40.5 ± 5.2 de | 27.5 ± 4.9 ab | |

| df | 530 | 474 | 55 | 530 | 474 | 55 | 530 | 474 | 55 | ||||

| F | 15.6 | 19.2 | 5.8 | 17.1 | 22 | 2.9 | 15.6 | 19.4 | 3.7 | ||||

| p | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sripho, S.; Chaiyarat, R. The Relationship between Population Density and Body Size of the Giant Mountain Crab Indochinamon bhumibol (Naiyanetr, 2001), an Endangered Species of Freshwater Crab from Northeastern Thailand (Potamoidea: Potamidae). Diversity 2022, 14, 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080682

Sripho S, Chaiyarat R. The Relationship between Population Density and Body Size of the Giant Mountain Crab Indochinamon bhumibol (Naiyanetr, 2001), an Endangered Species of Freshwater Crab from Northeastern Thailand (Potamoidea: Potamidae). Diversity. 2022; 14(8):682. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080682

Chicago/Turabian StyleSripho, Sirikorn, and Rattanawat Chaiyarat. 2022. "The Relationship between Population Density and Body Size of the Giant Mountain Crab Indochinamon bhumibol (Naiyanetr, 2001), an Endangered Species of Freshwater Crab from Northeastern Thailand (Potamoidea: Potamidae)" Diversity 14, no. 8: 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080682

APA StyleSripho, S., & Chaiyarat, R. (2022). The Relationship between Population Density and Body Size of the Giant Mountain Crab Indochinamon bhumibol (Naiyanetr, 2001), an Endangered Species of Freshwater Crab from Northeastern Thailand (Potamoidea: Potamidae). Diversity, 14(8), 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080682