Abstract

Habitat fragmentation is often assumed to negatively impact species diversity because smaller, more isolated populations on smaller habitat patches are at a higher extinction risk. However, some empirical and theoretical studies suggest that landscapes with numerous small habitat patches may support higher species richness, although the circumstances remain elusive. We used an agent-based metacommunity model to investigate this and simulate landscapes of the same total area but diverse patch sizes. Our model, as generic and unbiased by specific assumptions as possible, aimed to explore which circumstances may be more conducive to supporting higher biodiversity. To this end, most parameters and behaviors were random. The model included generalized species traits, dispersal, and interactions to explore species richness dynamics in fragmented landscapes of distinct patch sizes. Our results show that landscapes with many small patches maintain higher species richness than those with fewer large patches. Moreover, the relationship between patch connectivity and species richness is more pronounced in landscapes with smaller patches. High connectivity in these landscapes may support species diversity by preventing local extinctions and facilitating recolonization. In contrast, connectivity is less significant in large-patch landscapes, where generalist species dominate. The findings highlight the complex interplay between patch size quality, connectivity, species traits, and diverse interactions among species in determining species richness. We suggest the patterns produced by the model represent null predictions and may be useful as a reference for a diversity of more specialized questions and predictions. These insights may also have specific implications for conservation strategies, suggesting that maintaining a mosaic of small, well-connected patches could enhance biodiversity in fragmented landscapes.

1. Introduction

Ecologists often assume that habitat fragmentation negatively correlates with species diversity, as small populations and patch isolation reduce population survival probability [1,2]. At the same time, observations that many small patches can harbor higher species richness than large patches in the same total habitat area were quite frequent [3]. Recently, more comprehensive empirical research [4] makes a compelling case that landscapes support more species when the patches are many and small, given the same area and sampling effort. At the same time, a review by Riva et al. [5] identified five studies (between 2017 and 2022) where habitat fragmentation per se affected species richness, with one suggesting a positive effect. Some other theoretical studies suggest that increased fragmentation and a decline in concomitant patch size may lead to higher landscape diversity under some circumstances. Possible mechanisms for higher species richness in small-patch landscapes include (a) higher heterogeneity, e.g., [6], combined with (b) a lower number of species on small patches, (c) opportunities for specialization, (d) higher turnover, e.g., Chase et al. [2], and (d) metapopulation dynamics leading to differential tracking of different spatial resources (this aspect complements “d”). For example, Campos et al. [7] concluded that smaller, more numerous habitat patches support greater species diversity due to increased species dispersal and colonization opportunities, which involves several earlier processes. Others noted the edge effect increases with the patch size decline [8] and likely offers additional habitat heterogeneity for some species to exploit. These findings provide a reasonable argument for a possible positive effect of small habitat size and landscape fragmentation on species richness, at least in a portion of examined landscapes. However, the trend distilled from the extensive data set reveals high noise and frequent departures associated with specific landscapes and taxa. It also leaves the conditions under which these departures occur and possible factors responsible for the departures largely unexplored, primarily due to a lack of relevant data. Because the discovered trend is superficially counterintuitive [5], explanations inevitably grapple with substantial variability among individual studies and, possibly, circular logic, such as defining generalists as species not declining or increasing in abundance. The most recent theoretical study by Zhang et al. [9] attempts to explain the diversity of patterns. It finds conditional evidence for a positive effect of habitat size reduction on biodiversity. This effect is not straightforward, however. In their model, it depends on the total amount of habitat.

Furthermore, the results do not appear definitive, as they rely on one type of interaction—competition—and a rather specific set of traits arising from adopting the competition–colonization model. Simulated landscapes do not include other interactions and several essential features of the landscape, such as inter-habitat differences and species specialization. In short, the recent studies inspire further questions and suggest a need for a broader look. To answer some of these questions, we used an object-based metacommunity model. The model design attempted to include a broader set of general processes to avoid outcomes arising from specific model features.

To explore the effect of patch size, we created small-, medium-, and large-patch landscapes and monitored the patch connectivity. The dependent variables included species richness and population density. We used an agent-based, spatially explicit metacommunity model where species gain energy on ‘suitable’ patches, with dispersal and reproduction costing energy and species interactions involving costs and rewards on the gradient from negative to positive interactions. To examine the effect of patch size on species richness, we have focused on specific landscape features (see Methods: Model, Species, and Data Collection sections). Applying a metacommunity model allows for examining interactions of processes such as dispersal, various species interactions, level of heterogeneity, and population rescue on species diversity as a function of patch size—the variable of considerable theoretical and practical interest. By modeling landscapes of the same total area regardless of the size and number of habitat patches, the exercise suggests definitive answers to other hypotheses, such as the habitat amount or multi-dimensional hypotheses, cf. [10]. We focused on the hypothesis that the species richness will be higher in landscapes with smaller patches than in landscapes with larger patches as long as they feature similar spatial patterns, total habitat area, species movement probability, habitat heterogeneity, species interactions, dispersal networks, and reproduction rules.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Model

We used a generalized metacommunity model [11] to examine the effects of habitat size in three fragmented landscapes (please see Supplementary Materials for more details). A recent study concerned with the effects of habitat fragmentation and habitat patch size [9] also uses a metacommunity model, although it differs in various aspects. Our model’s major features are as follows:

2.1.1. Landscape

The landscapes always maintained the same total area regardless of the patch size. Each run of the model used a new landscape (25, 81, or 121 patches) of patches with randomly assigned suitability values and correspondingly smaller fractions of the total landscape area. We diversified patches by randomly assigning a habitat suitability value to create inter-habitat differences (heterogeneity) to which species could respond. Ref. [12] advocated this feature as crucial to understanding the consequences of habitat fragmentation. Suitability values define a range of patches a species can use without a penalty. A match of a species specialization and the patch suitability value jointly define the species access to that and similar patches. Each patch regenerates energy (resources that any species can use) at a predefined rate and loses it depending on the number of individuals that can use its resources. Individuals of species arriving on a patch incompatible with their requirements cannot use its resources—such species lose energy until they find a suitable patch. In contrast, the Zhang et al. model [9] uses mean patch size in virtual landscapes comprising a mix of patch sizes.

2.1.2. Species Specialization

Specialization is a function of habitat use. Generalists can use a broad range of habitat suitability values. Specialists use a smaller range of habitats. The specialization gradient is continuous and tracked in increments of 0.2 on the scale from 0 to 1. Each species receives a separate random specialization value for each replicate run.

2.1.3. Species Interactions

Species interactions can be positive and negative, with values of −1, 0, and +1 assigned randomly and separately for each of the ten runs of the model. When individuals of two species meet, they generate additional or lose available energy units depending on their assigned interaction value (two positive values mimic mutualism, two negative competition, and other combinations of positive and zero or negative values mimic other types of interspecific interactions). Indirect interactions are implicit. They occur in different configurations depending on the mix of species in a patch. Interaction cascades are possible with more species in a patch (e.g., if species A hurts B, B’s negative impact on C is reduced, or if A has a positive impact on B, and B has a negative impact on C, it amplifies C’s loss). Competition occurs by default because all individuals dispersing into a patch require energy. The energy supply fluctuates (consumption and regeneration) on a single patch as a function of its size to equalize its availability among landscapes but is limited for the landscape as a unit through the carrying capacity of the combined populations. Predation is not explicit because its outcome cannot be qualitatively distinguished from other interactions, i.e., an individual can lose energy by encountering a competitor or a predator and gain energy when it encounters a mutualist (or abundant resource on a landscape patch). Crucially, our choices reflect a degree of indeterminacy afflicting interaction outcomes in multi-species matrices [13]. It is reasonable to assume that meta-habitat settings compound this indeterminacy.

2.1.4. Dispersal

When they have enough energy, individuals of any species can move/disperse or reproduce once in each step of the model run. The choice to move or reproduce is random. They move one habitat patch at a time. If they land on a patch that is not suitable, they lose energy. They die when their energy is limited, so they can neither move nor reproduce. This happens when the patch is unsuitable, or other species depleted its energy. The direction of movement is random. However, due to landscape connectivity differing among separate runs of the model, the dispersal network heterogeneity would also differ and may have contributed to the species richness variance as postulated by Savary et al. [14]. We used a proxy measure of mean patch connectivity to keep track of this contribution. We scored the latter by counting connected patches in each new landscape configuration and obtaining the ratio of those patches to all the patches (the connectivity index). In preliminary analyses, we confirmed that the mean connectivity did not differ among the three landscape types.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

We ran the model for 500 generations and concurrent dispersal steps (an agent can reproduce or move in each step). We analyzed the steady-state landscape richness represented by the terminal state of the virtual metacommunity model and thus skirted the issue of successional change [15]. Each landscape patch size treatment had ten replicated runs, with all of the data used in the analyses. The degree of connectivity generated in a landscape involved assessing the fraction of patches that were immediate neighbors to at least one patch of the same suitability. This is a simplified analog of ‘clustering’ used by [16] and a coarse indicator of the dispersal network heterogeneity [14]. When the metric attains the value of 1, then no patch is alone. This, however, does not imply complete landscape connectivity because various configurations of connected patches still present differential dispersal impediments that we did not quantify. This residual isolation of patch clusters does contribute to connectivity variance. We used the General Linear Model analyses (Statistica, version 13.5 (2022) from TBCO) to examine the main treatment effect and their interactions among treatments.

A recent study concerned with the effects of habitat fragmentation and habitat patch size [9] also uses a metacommunity model, although our model differs from the model used by Zhang et al. [9] in several aspects:

- ○

- Dispersal from patches is a function of the patch state (i.e., the number of individuals, instantaneous positive and negative interactions arising from attributes of specific species present at the time, resources available to individuals—a function of combined N of all species).

- ○

- Interactions range from negative to positive.

- ○

- All simulated landscapes had the same level of inter-habitat differences, i.e., each patch has the same probability of being in contact with four other patches with one of the five suitability classes.

- ○

- Landscape connectivity was a function of the proximity of suitable patches. Specifically, a patch of similar suitability class did not tax the disperser’s condition (available energy) when an individual immigrated to it, but unsuitable patches did. Locations of patches of different suitability in each landscape were random. Overall, higher patch connectivity implies an easier dispersal for a given configuration of patches, as suggested by Savary et al. [14].

- ○

- Patch suitability was random and carried costs to species, which depended on the mismatch between species specialization and habitat suitability.

3. Results

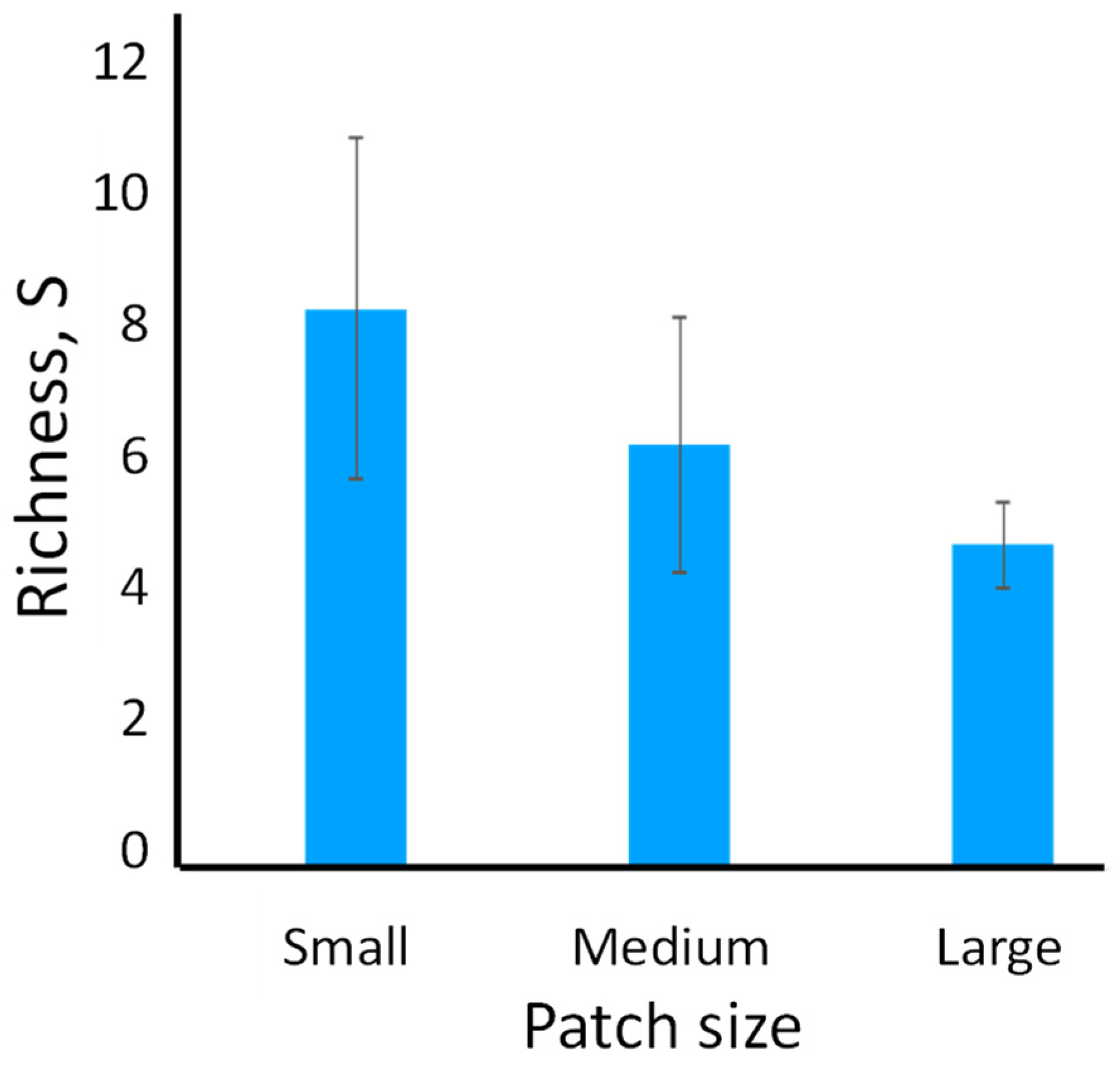

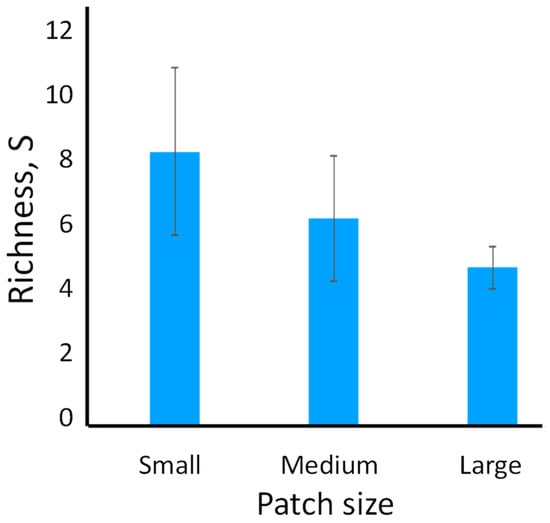

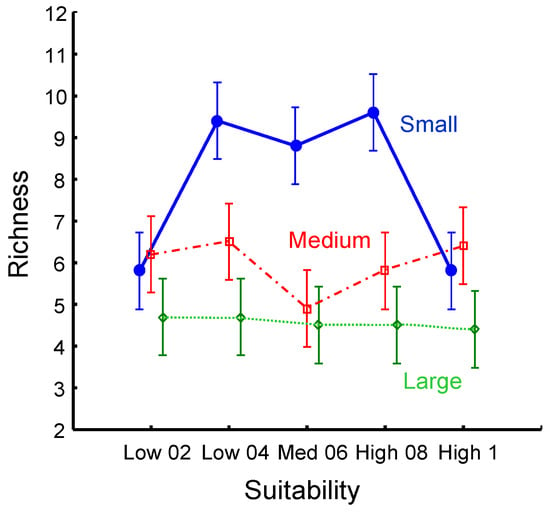

We found that landscapes with many small patches maintained twice as many species as landscapes with patches about twice as large in area (Figure 1). The question arises regarding the mechanisms supporting higher richness in smaller patches. Riva and Fahrig [4] reported a bewildering range of responses along the patch size axis. Interpreting the relationship between species richness and habitat size is likely to interact with other ecological factors. Some such factors may include habitat connectivity, depth of inter-habitat differences, and species specialization to habitat types.

Figure 1.

Mean richness in landscapes containing large, medium, and small patches. Error bars are standard deviations.

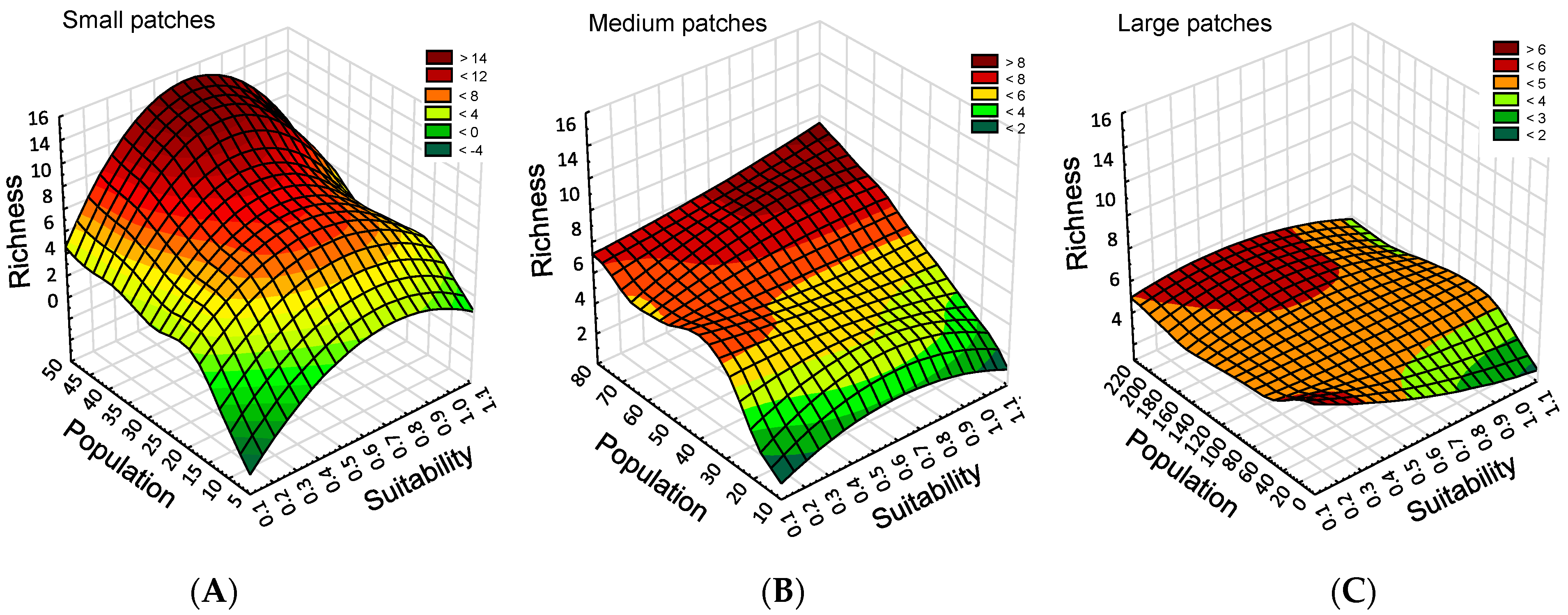

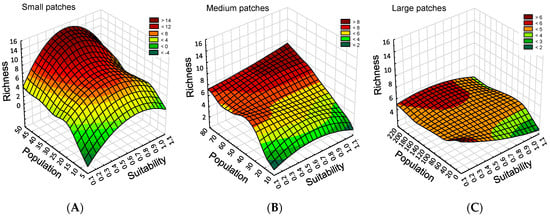

First, we notice that when the combined population of all species increases, the species richness declines (Figure 2). As the total landscape population increases with the patch size, a new question arises about the causes. Do larger patches allow for greater total populations, a factor that could leave a few more successful species to dominate the landscape? Alternatively, does increasing fragmentation (and an ensuing patch size reduction) promote a tradeoff between colonization and extinction, cf. [17], such that no species can monopolize most patches? The latter process might also interact with inter-habitat differences, where habitat specialists might succeed in only some locations.

Figure 2.

A partial visual summary of results (distance weighted least squares fit): Richness patterns as a function of patch size, habitat suitability, and mean combined population of all species per patch suitability class surviving in the landscape at the end of a simulation run. Each suitability class comprised, on average, 5, ~13, and ~24 patches in small- (A), medium- (B), and large-patch landscapes (C), respectively. All charts are scaled to a richness of 16, but use separate scales for population density per suitability class (five classes) due to substantial differences emerging among the three landscape types.

The responses (Figure 2) suggest that the most likely culprits are local patch processes rather than the landscape population size of combined species. Here, whether the population is low or high, species richness remains similar. Small-patch landscapes offer more spatial patch diversity and support more specialists (Figure 2A; the majority of species seeded in the model), while large-patch landscapes appear to represent functional homogenization [18], with a few generalists dominating (Figure 2C).

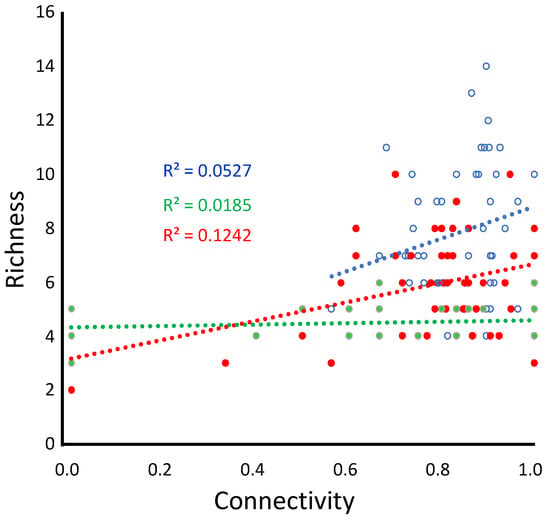

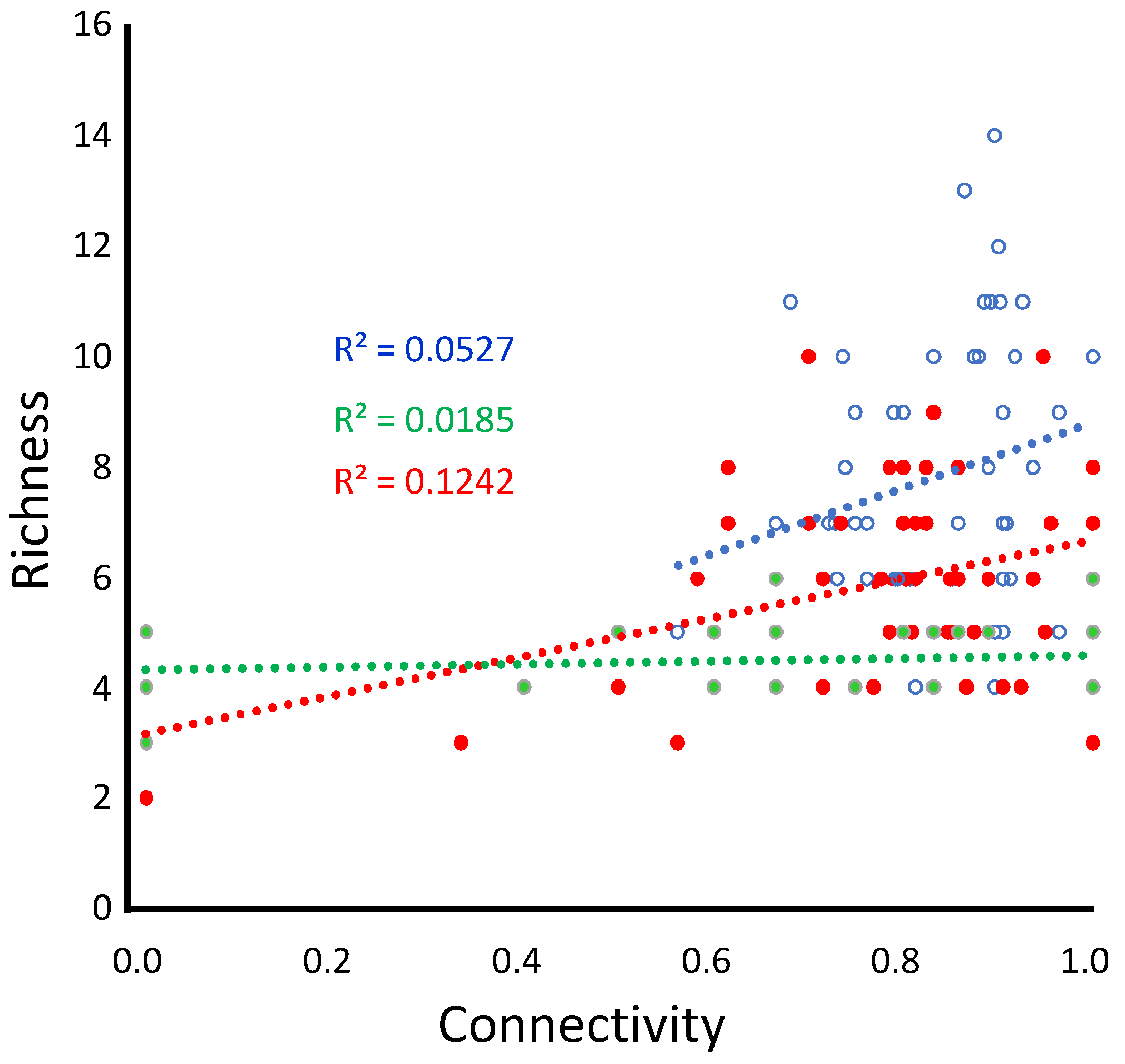

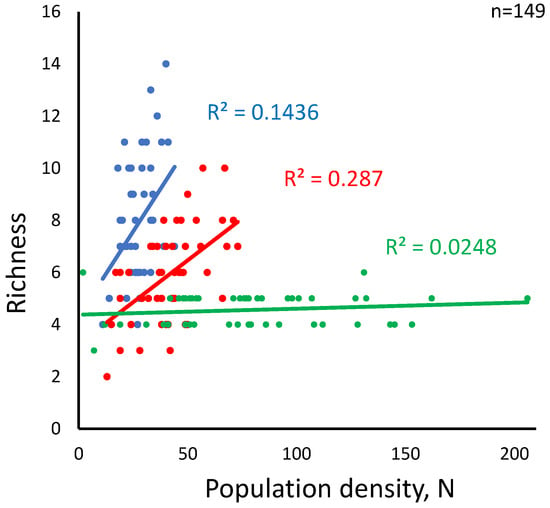

The relationship between habitat connectivity, a proxy metric for higher effective dispersal, and richness reveals no response in large-patch landscapes (Figure 2C), 12% of variance explained in medium-patch landscapes (Figure 2B), and 5% in small-patch landscapes. This is not to say that connectivity does not play a role. More likely, there is a shift in importance from small-patch landscapes (limited resources, increased variability in dispersal success) (Figure 2A and Figure 3) to larger patch sizes (Figure 2C) where generalist species appear to flood the landscape.

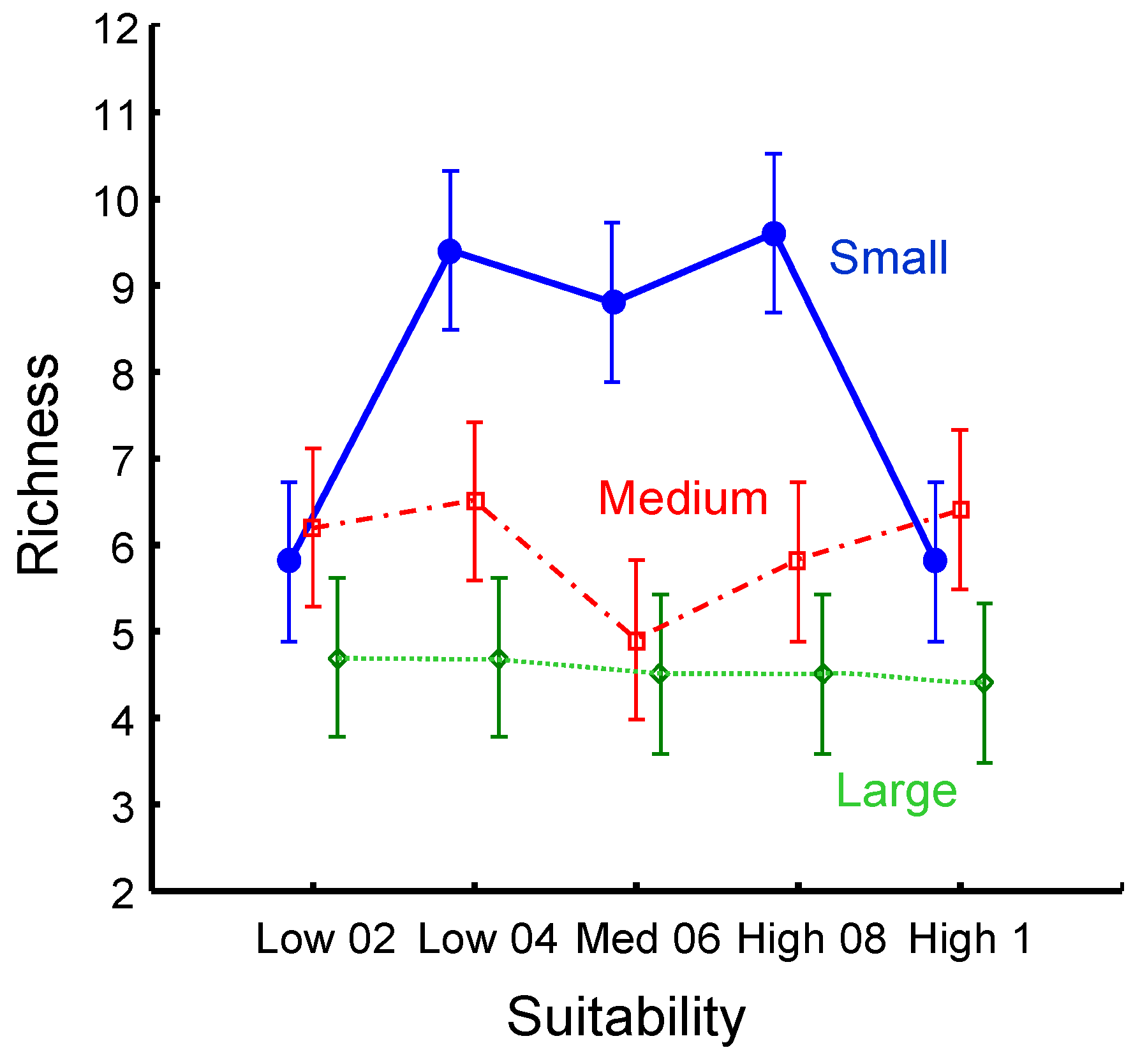

Figure 3.

Effect of connectivity (measured as mean patch adjacency), for small- (blue open circles), medium- (red), and large- (green) patch landscapes (details in Table 1). Regression slopes are 0.230 (not significant), 0.352 *, and 0.136 (not significant), respectively. Significant regressions and effects are marked with an asterisk.

Table 1.

Effects of all tracked variables on species richness, GLM. Note that patch size, population size, and habitat suitability have the strongest explanatory value, respectively, while connectivity has a low predictive value. Standard error of estimate: 1.66. Significant relationships are denoted by an asterisk in the probability, p, column.

Figure 3.

Effect of connectivity (measured as mean patch adjacency), for small- (blue open circles), medium- (red), and large- (green) patch landscapes (details in Table 1). Regression slopes are 0.230 (not significant), 0.352 *, and 0.136 (not significant), respectively. Significant regressions and effects are marked with an asterisk.

While the patterns associated with connectivity are weak, they are statistically significant (Figure 3, Table 2) and likely relevant in nature.

Table 2.

Details for the effect of habitat size and its connectivity on richness (ANOVA). Univariate tests of significance, standard error of estimate: 1.74. Significant effects are marked by an asterisk.

As we suspected, the ability to disperse appears to have contributed to higher landscape richness in small- and medium-patch landscapes. In large-patch landscapes, dispersal may play a lesser role as movement among patches is less important for obtaining resources and reducing dispersal costs. This change in the playing field may allow habitat generalists to dominate numerically; see also [19] for compatible results.

Connectivity did not contribute to the explanation of richness differences among landscapes, although it should not be dismissed (Table 1). Low connectivity negatively impacted richness, particularly in small-patch landscapes where no species survived below the 0.5 value of the connectivity metric. Meta-analyses of empirical patterns likely include both situations, and depending on their mix, we should expect to see either type of effect.

A plausible interpretation is that a meta-habitat comprising many small and different patches (high heterogeneity) is conducive to the coexistence of many different species, e.g., [20], but see also [21]. Here, higher patch connectivity supports significantly higher richness by either protecting small populations from local extinction or successfully restoring locally extinct species such that in the long run (of the model) species seeded at the beginning of the simulations survived in the landscape. The effect of connectivity among large patches on richness is statistically insignificant. This dual effect of patch size and connectivity may create a stage for high richness and dispersal by more specialized species. While connectivity effects differ among landscapes of different patch sizes, they become marginally significant when evaluated in the combined context of more important factors such as patch size, suitability, and aggregated population of all species (Table 1).

Maintaining a sufficient population size to track suitable habitats, especially when a species is a habitat specialist, can also provide insights into richness-promoting factors (Figure 4). The suitability effect is unimodal-like and prominent when the patches are small. The effect disappears in medium and large patches. The low species richness in low-suitability habitats concurs with the low density of the aggregate population.

Figure 4.

Habitat suitability has a non-linear effect on richness only in small-patch but not in medium- and large-patch landscapes. Lines show species richness in respective patch-size landscapes (details in Table 3).

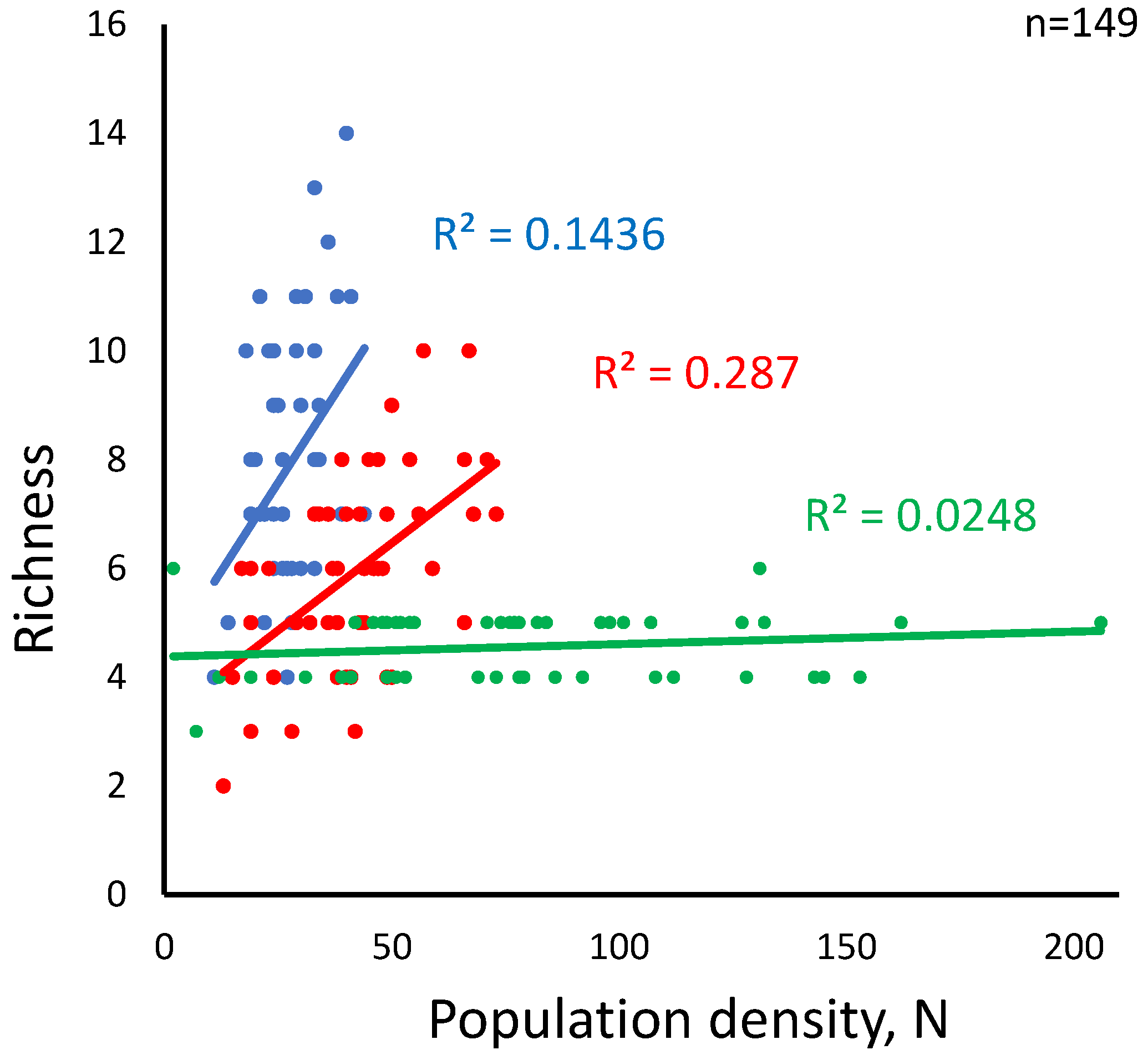

While differences among the three landscape types are clear (p < 0.0000), the aggregate population size is unrelated to habitat suitability (ANCOVA, p = 0.764). However, within treatments, the population size positively correlates with richness in medium- and small-patch landscapes but shows no correlation in large-patch landscapes (Figure 5). As high total population correlates negatively with richness in large-patch landscapes, a plausible explanation might be that in such landscapes, a decline in spatial habitat turnover per unit distance reduces dispersal costs for a limited number of species at the expense of other, less competitive species. Another related interpretation might involve dispersal network heterogeneity if it varied as a function of the patch size. We cannot determine this directly at this stage, but we saw neither effect of patch size on mean connectivity among the landscape type (One-way ANOVA F(2, 147) = 0.606, p = 0.547) nor any interaction effect of habitat suitability category and the patch size.

Figure 5.

Richness increases significantly with the mean population density per habitat suitability class in small- and medium-patch landscapes and does not change in large-patch landscapes. Population density is a mean combined species populations within a habitat suitability class. Regression slopes are 0.379 (significant at p = 0.05), 0.536 (significant at p = 0.05), and 0.158 (not significant). The regression line slopes visually mismatch the slope values because they scale differently with N.

Nevertheless, the above result challenges a straightforward interpretation in ecological terms. This is because simulated data and natural systems allow additional factors to modulate the effects of the factors of interest. These range from static spatial configurations to dynamic biological interactions and generate many reasonable expectations. In our model, habitat suitability sheds some light on the unfolding relationships.

Habitat suitability strongly promotes species richness in the small-patch landscapes, although only in the middle of the suitability range. Its effect in other landscapes declines sharply, although it may have some influence in medium-sized patch landscapes when the population is relatively high (Figure 4, Table 1).

The pattern of declining effect of habitat suitability and population size is consistent with the idea that habitat fragmentation and diversity of habitat types form a combination of conditions that imposes sufficient limitations on the success of habitat generalists. This limitation may allow local yet highly uneven persistence of habitat specialists in small-patch landscapes. As the species number declines on a gradient from small to large patches, the ratio of specialists to generalists shrinks from 2.9, 1.3, and 1.1, respectively. The pattern supports expectations that generalists perform better where the spectrum of different and isolated conditions does not protect specialists from negative interactions. Additionally, much higher landscape population density may exacerbate the negative interactions through resource competition.

4. Discussion

The most significant finding is a confirmation that, in an unbiased model, small-patch landscapes can support higher species richness than other landscapes (in the model, this support is expressed as the most modest species losses over 500 generations in the simulated community). This support correlates with the lowest combined density of all species over the landscape. Empirical research shows that among many different factors, uneven dispersal of species (uneven spatial isolation, heterogeneity) may significantly influence species richness due to differential species abilities and uneven accessibility of patches [22]. Our simulations allow for such effects implicitly, but we do not know how the habitat size affects them because the overall connectivity and habitat suitability distributions did not differ between the landscape types (Section 3).

The patterns exhibited by generalist species appear in line with the observations in nature, underscoring the generalists as being more abundant, less variable, and present in a broader range of habitat types (here defined by differences in suitability). However, the generalists’ contribution does not support the hypothesis suggesting they boost increasing biodiversity in small-patch landscapes, cf. [4]. This result could arise from the model choice of allowing only 10% of species to have the broadest ranges of habitat use. The generalists’ impact may, however, materialize differently. Specifically, the species diversity exhibits a unimodal relationship with habitat suitability in the small-patch landscapes. The unimodal response may suggest that the highest habitat suitability (in nature, it could be an abundance of resources) may increase extinction risks for unknown reasons, possibly translating into the high density of a few successful generalist species.

Our results support the recent empirical findings [4] that local reduction of biodiversity in small habitats may allow an opposite trend for higher biodiversity at the landscape level. Recent models, e.g., [9], support some features of our simulation, but others, e.g., ref. [23] show contradictory results. These similarities and differences may reflect variation based on observed data from natural systems. In contrast, different conclusions among simulated metacommunities are more likely due to specific assumptions and the choice of variables in the models. For example, Guo et al. [23] examined food webs with competition–colonization tradeoffs among basal species, omnivores, and other secondary consumers, and found a broad range of outcomes. Importantly, they show habitat loss would lead to topology oscillations and changes in species number dependent on the spread of omnivory, habitat loss, and basal species colonization success. By being more general in treating species interactions, our model may be missing some of the more specific processes they identified, e.g., the role of basal species. The differences among conclusions and underlying model premises strongly suggest a need for a general framework that is simple, integrated, and comprehensive. Without such a framework, the diversity of findings may end up more confusing than illuminating.

Our approach and data differ in some respects from those presented in the recent study of natural data sets [4]. Some disparity is not surprising given the differing research questions in each study. Our model simulation focused on contrasts arising solely from habitat patch size. All patches in a landscape had the same size and shape, and all the remaining landscape/patches/species settings were the same across landscape size types, which is not the case in natural systems.

Although the initial settings other than patch size were identical, this does not mean our simulated landscapes are identical. Differences emerge from random variation and may have some effect on landscape patch structure (connectivity), local and global species composition, interactions, specialization, and dispersal. The Riva and Fahrig study [4] included a variable mix of small and large patches. We examined the performance of identically constructed species sets across those three landscape times, while the empirical study [4] compared one species set on small and one on large patches in many different landscapes where species specialization, interaction intensity, and dispersal rates were largely unknown.

The trends observed in individual data sets examined by Riva and Fahrig contribute to noise that may add to a significant scatter of correlations and mask the relationship between the species richness and patch size. This inevitable feature of the inductive approach generates uncertainty and vague answers because of many possible causes. One possibility stands out. Unless the patches analyzed by Riva and Fahrig [4] had the same size structure distribution across the data sets, which they certainly could not, the patterns they found might be artefactual to some degree, i.e., biased by mechanisms prevailing in large or small patches in a particular landscape. Furthermore, the individual data sets may have had different species–habitat relationships, contingent on the species–habitat specialization relative to habitat mosaic attributes, including the suitability of individual patches. In this context, a lack of support for the habitat amount hypothesis (cf. [24]) in our results is relevant to establishing null expectations and providing a universal reference for past and future comparisons.

In our simulations, all patches were of the same size within the landscape type. While this is a software limitation, size homogeneity offers some advantages because size differences may exaggerate differences in species performance and mask the patch size effects. We will keep this potentially influential difference in mind when highlighting putative lessons from our analyses.

Earlier empirical studies also occasionally found that smaller patches, when representing more heterogeneity (habitat type diversity), can support more species than other patches [25]. While our model had the same settings of habitat suitability for all three landscape types, the landscape with the smallest patches may exhibit the most significant heterogeneity for at least one reason. Smaller patches show a higher temporal variability of local richness and species identity, enhancing the heterogeneity of resources and unpredictability of interactions on individual patches of the same suitability level. An experimental study associated this variability with the variability of species interactions in fragmented landscapes [26]. Another coexistence mechanism may possibly involve a local competitive advantage of good dispersers [27].

Implications. If our findings reflect null trends adequately, habitat suitability models aiming at biodiversity conservation should consider a specific species class—one including species particularly adept at using small habitats. This implication should not be surprising because habitat suitability models successfully couple the distribution of suitable patches and species requirements [28], while recognizing various sources of species/habitat mismatch and its consequences [27,29]. Other studies appear to emphasize the link and note that habitat quality may override the effect of habitat fragmentation (e.g., [30,31]). Both possibilities are relevant to biodiversity management and offer promising research pursuits.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d16110658/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. and J.M.; methodology, J.K.; software, J.M.; validation, J.K. and J.M.; formal analysis, J.K.; investigation, J.M.; resources, J.K. and J.M.; data curation, J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, J.K. and J.M.; visualization, J.K.; supervision, J.K.; project administration, J.K.; funding acquisition, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Grant number 10531314) and APC was funded by MDPI.

Data Availability Statement

The data file is available at Borealis Dataverse (McMaster University). URL accessed on 9 of October 2024. https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/PKZMKA.

Acknowledgments

Joyce Yan coded the basic metacommunity model, and Kevin Zheng inspired this study by identifying an unexpected pattern of metacommunity behavior). Two anonymous reviewers provided valuable suggestions for improving the manuscript, for which we are most grateful.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wintle, B.A.; Kujala, H.; Whitehead, A.; Cameron, A.; Veloz, S.; Kukkala, A.; Moilanen, A.; Gordon, A.; Lentini, P.E.; Cadenhead, N.C.; et al. Global synthesis of conservation studies reveals the importance of small habitat patches for biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, J.M.; Blowes, S.A.; Knight, T.M.; Gerstner, K.; May, F. Ecosystem decay exacerbates biodiversity loss with habitat loss. Nature 2020, 584, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L. Why do several small patches hold more species than few large patches? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020, 29, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Fahrig, L. Landscape-scale habitat fragmentation is positively related to biodiversity, despite patch-scale ecosystem decay. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Koper, N.; Fahrig, L. Overcoming confusion and stigma in habitat fragmentation research. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Hur, E.; Kadmon, R. An experimental test of the area-heterogeneity tradeoff. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 4815–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, P.R.A.; Rosas, A.; de Oliveira, V.M.; Gomes, M.A.F. Effect of Landscape Structure on Species Diversity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J.J.; Gannon, D.G.; Hightower, J.; Kim, H.; Leimberger, K.G.; Macedo, R.; Rousseau, J.S.; Weldy, M.J.; Zitomer, R.A.; Fahrig, L.; et al. Toward conciliation in the habitat fragmentation and biodiversity debate. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 2717–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Chase, J.M.; Liao, J.B. Habitat amount modulates biodiversity responses to fragmentation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklarczyk, C.A.; Evans, K.O.; Greene, D.U.; Morin, D.J.; Iglay, R.B. Effects of spatial patterning within working pine forests on priority avian species in Mississippi. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 2019–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasa, J.; Hammond, M.P.; Yan, J. Metacommunity Research and the Entanglement of its Core Terms. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortelliti, A.; Amori, G.; Boitani, L. The role of habitat quality in fragmented landscapes: A conceptual overview and prospectus for future research. Oecologia 2010, 163, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawatsu, K. Unraveling emergent network indeterminacy in complex A random matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2322939121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savary, P.; Lessard, J.-P.; Peres-Neto, P.R. Heterogeneous dispersal networks to improve biodiversity science. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2024, 39, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howeth, J.G.; Lozier, J.D.; Olinger, C.T.; Dedmon, M.L.; Matthews, J.M.; Cardoza, S.J. Crayfish communities converge over succession in beaver pond metacommunities. Freshw. Biol. 2024, 69, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevides, C.R.; Evans, D.M.; Gaglianone, M.C. Comparing the Structure and Robustness of Passifloraceae—Floral Visitor and True Pollinator Networks in a Lowland Atlantic Forest. Sociobiology 2013, 60, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeuille, N.; Leibold, M.A. Effects of local negative feedbacks on the evolution of species within metacommunities. Ecol. Lett. 2014, 17, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavel, J.; Julliard, R.; Devictor, V. Worldwide decline of specialist species: Toward a global functional homogenization? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.L.; Simmons, B.; Fortin, M.J.; Gonzalez, A. Generalism drives abundance: A computational causal discovery approach. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.R.; Bastos, D.A.; Sousa, L.M.; Giarrizzo, T.; Vieira, T.B.; Hepp, L.U. Metacommunity organisation of Amazonian stream fish assemblages: The importance of spatial and environmental factors. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2024, 33, e12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardanico, J.; Hovestadt, T. Effects of compositional heterogeneity and spatial autocorrelation on richness and diversity in simulated landscapes. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borthagaray, A.I.; Cunillera-Montcusí, D.; Bou, J.; Tornero, I.; Boix, D.; Anton-Pardo, M.; Ortiz, E.; Mehner, T.; Quintana, X.D.; Gascón, S.; et al. Heterogeneity in the isolation of patches may be essential for the action of metacommunity mechanisms. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1125607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.M.; Zhao, F.; Nijs, I.; Liao, J.B. Colonization-competition dynamics of basal species shape food web complexity in island metacommunities. Mar. Life Sci. Tech. 2023, 2, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, S. The Habitat Amount Hypothesis implies negative effects of habitat fragmentation on species richness. J. Biogeogr. 2021, 48, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzkämper, A.; Lausch, A.; Seppelt, R. Optimizing landscape configuration to enhance habitat suitability for species with contrasting habitat requirements. Ecol. Model. 2006, 198, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsch, M.; Guex, I.; Todorov, H.; Heiman, C.M.; Vacheron, J.; Vorholt, J.A.; Keel, C.; van der Meer, J.R. Fragmented micro-growth habitats present opportunities for alternative competitive outcomes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerch, B.A.; Rudrapatna, A.; Rabi, N.; Wickman, J.; Koffel, T.; Klausmeier, C.A. Connecting local and regional scales with stochastic metacommunity models: Competition, ecological drift, and dispersal. Ecol. Monogr. 2023, 93, e1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amici, V.; Geri, F.; Battisti, C. An integrated method to create habitat suitability models for fragmented landscapes. J. Nat. Conserv. 2010, 18, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinuma, J.; Pärtel, M. Decomposing dark diversity affinities of species and sites using Bayesian method: What accounts for absences of species at suitable sites? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 1796–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.; Díaz, J.A.; Pérez-Tris, J.; Carbonell, R.; Tellería, J.L. Habitat quality predicts the distribution of a lizard in fragmented woodlands better than habitat fragmentation. Anim. Conserv. 2008, 11, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozada, A.; Day, C.C.; Landguth, E.L.; Bertin, A. Simulation-based insights into community uniqueness within fragmented landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 2533–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).