Revalidation of the Arboreal Asian Snake Genera Gonyophis Boulenger, 1891; Rhynchophis Mocquard, 1897; and Rhadinophis Vogt, 1922, with Description of a New Genus and Tribe (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae) †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

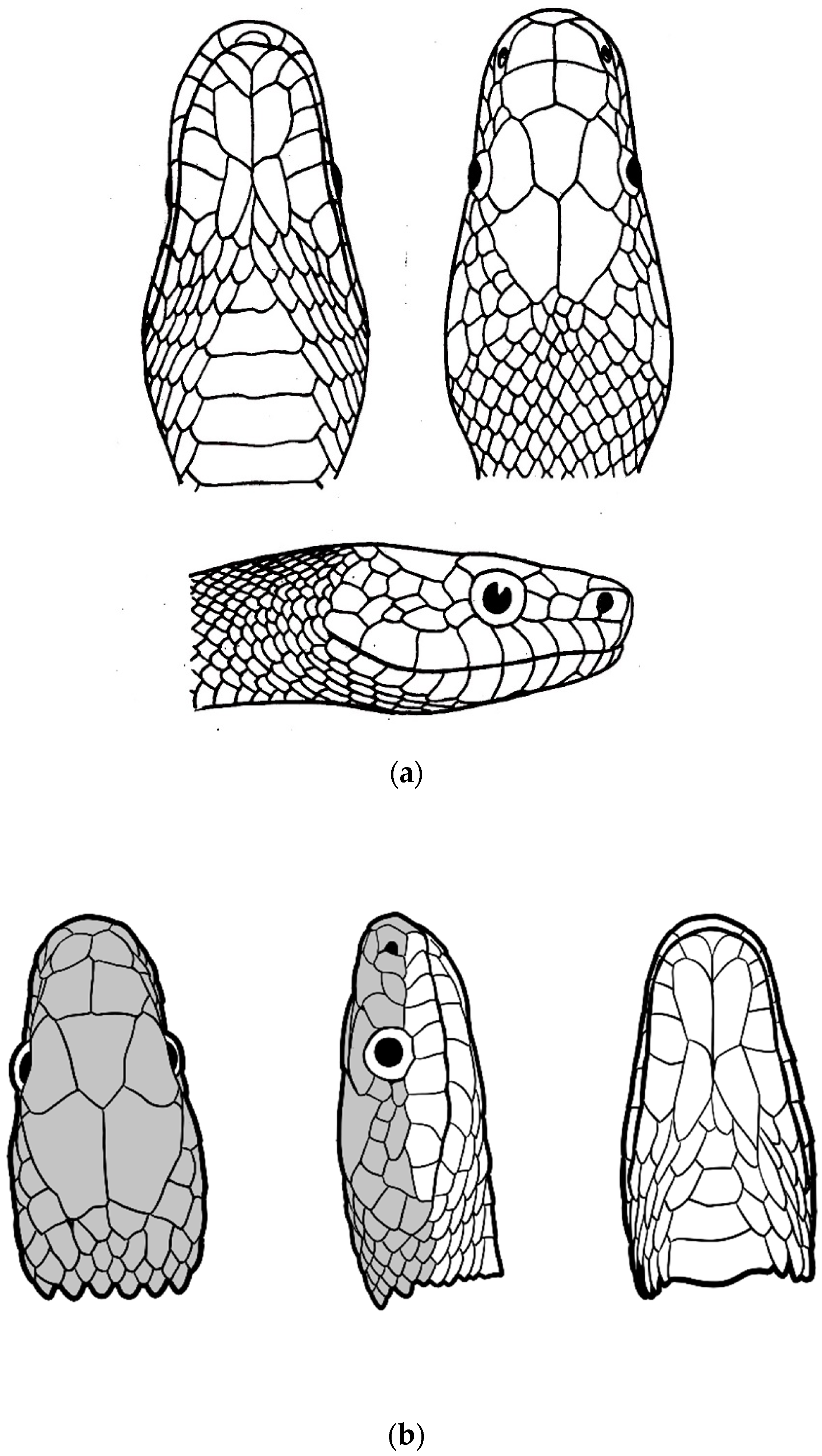

3.1. Gonyophis

Gonyophis margaritatus

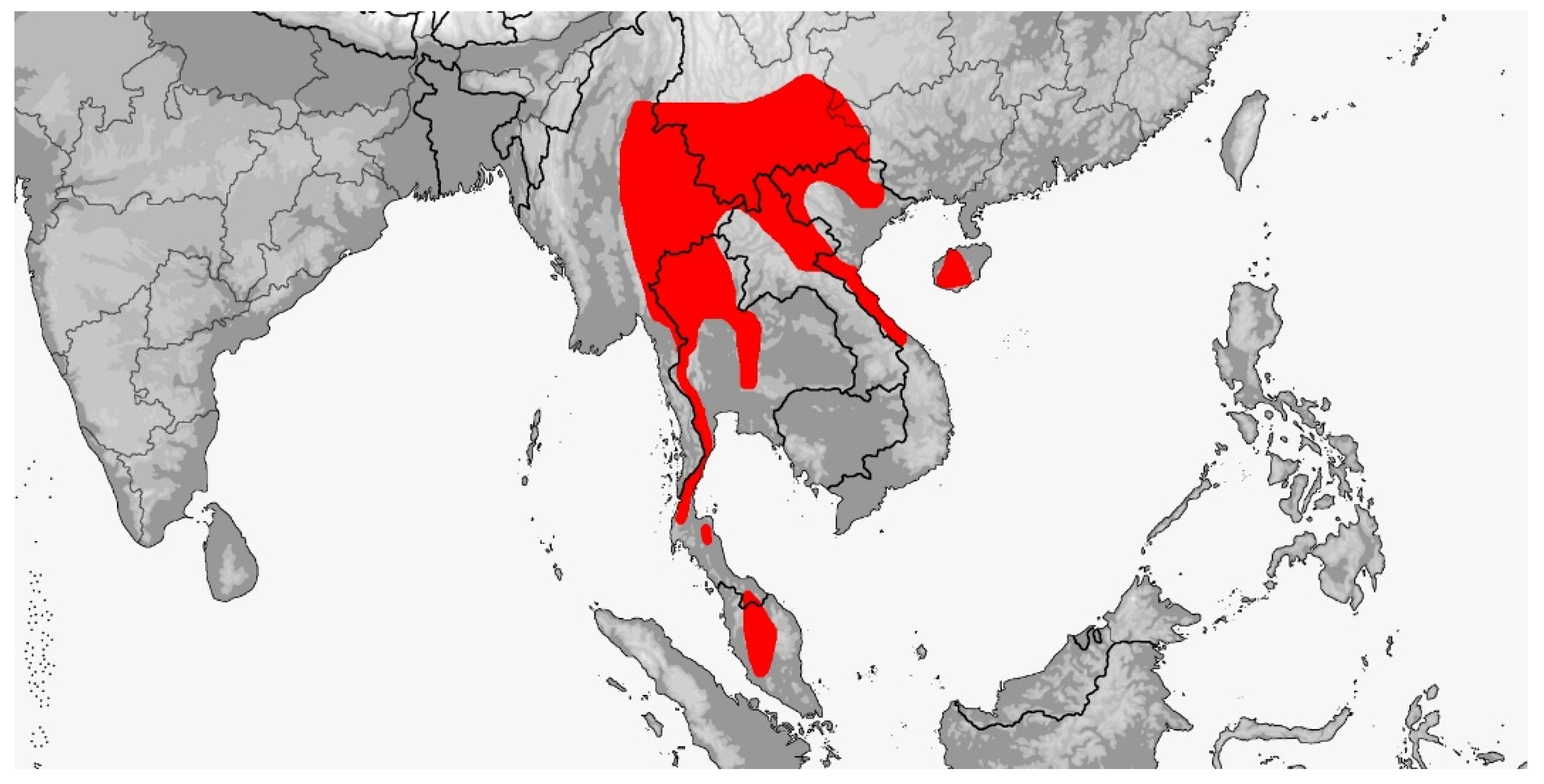

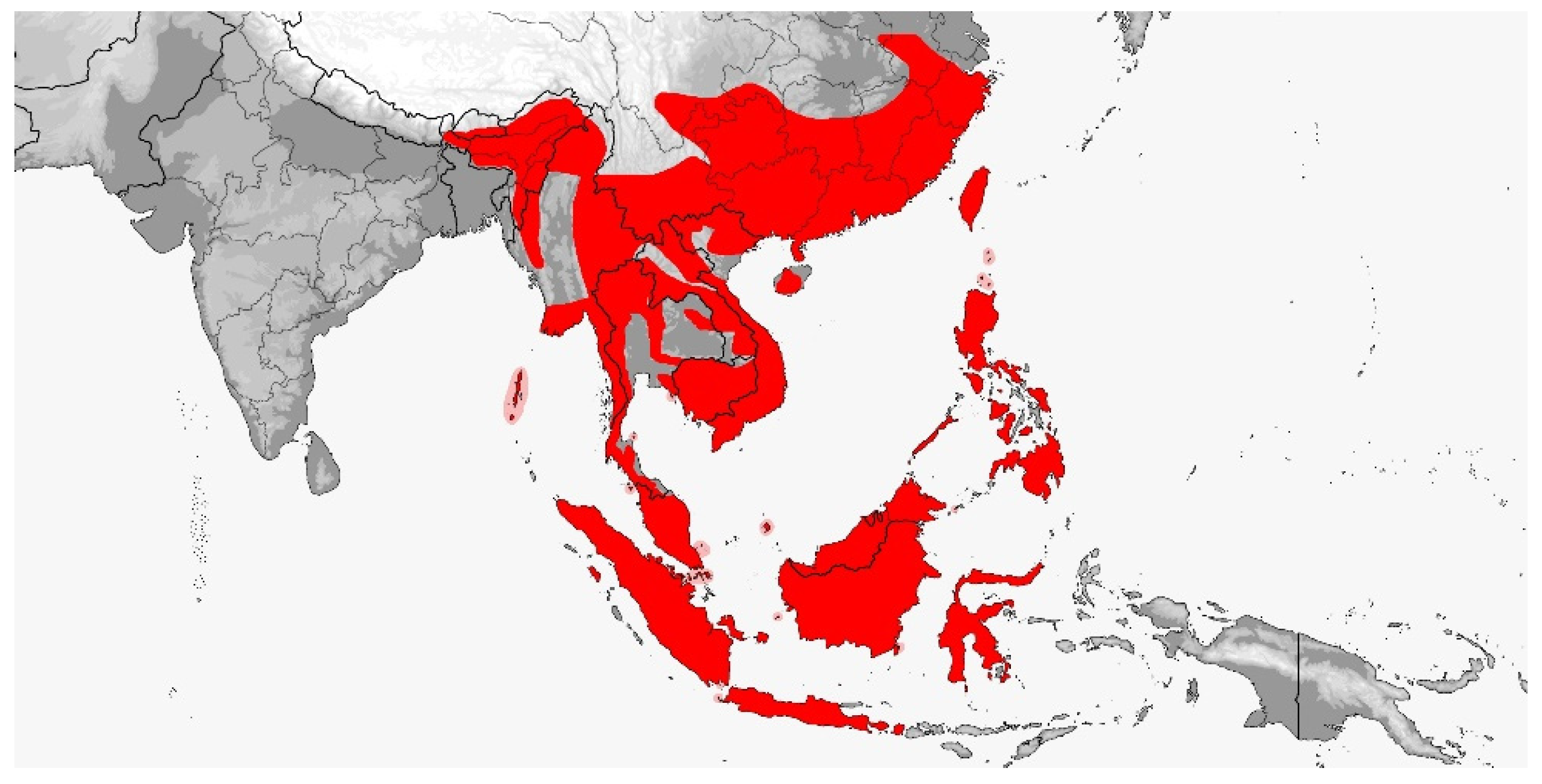

3.2. Gonyosoma

3.2.1. Gonyosoma jansenii

3.2.2. Gonyosoma oxycephalum

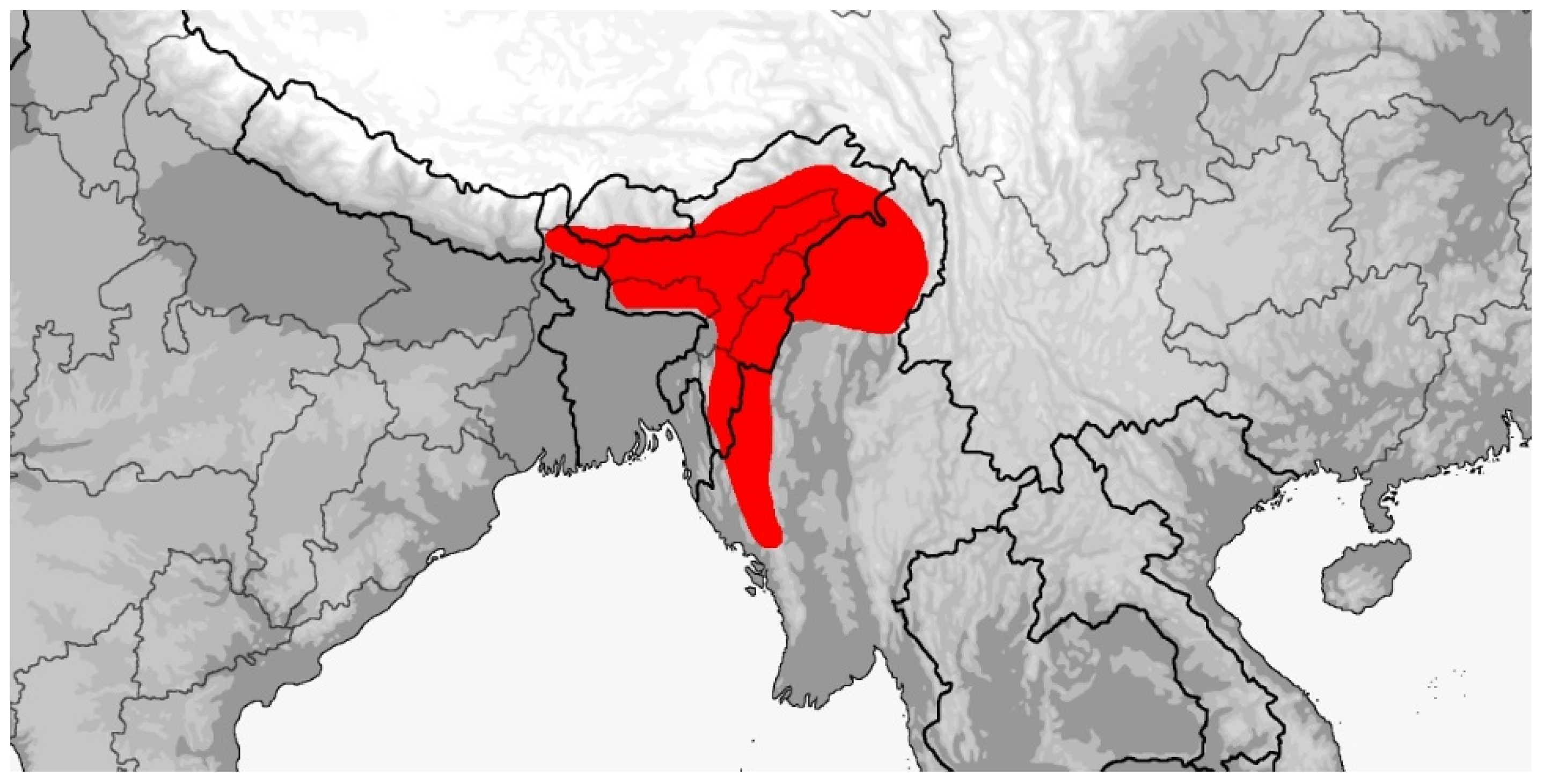

3.3. Rhadinophis

Rhadinophis frenatus

3.4. Rhynchophis

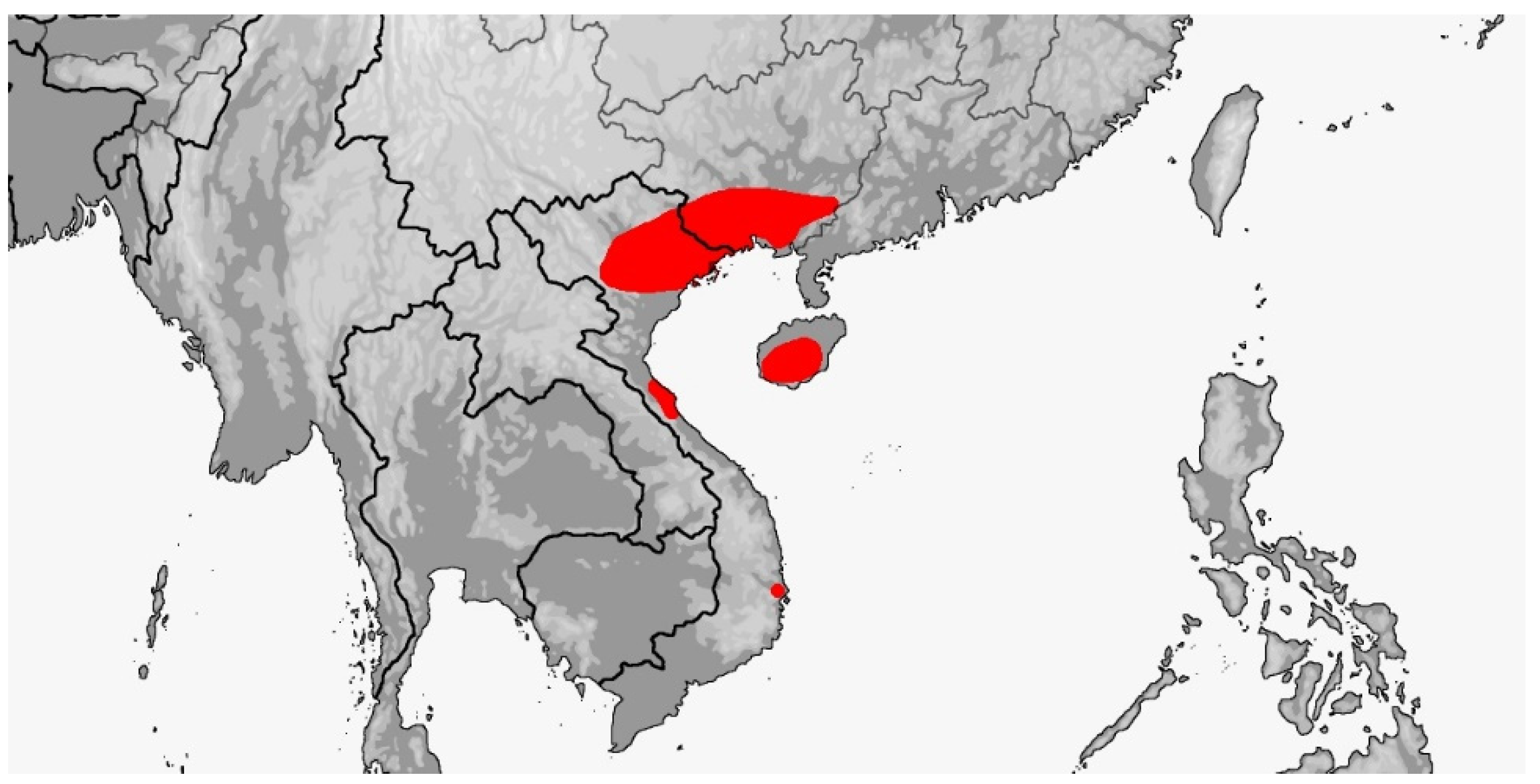

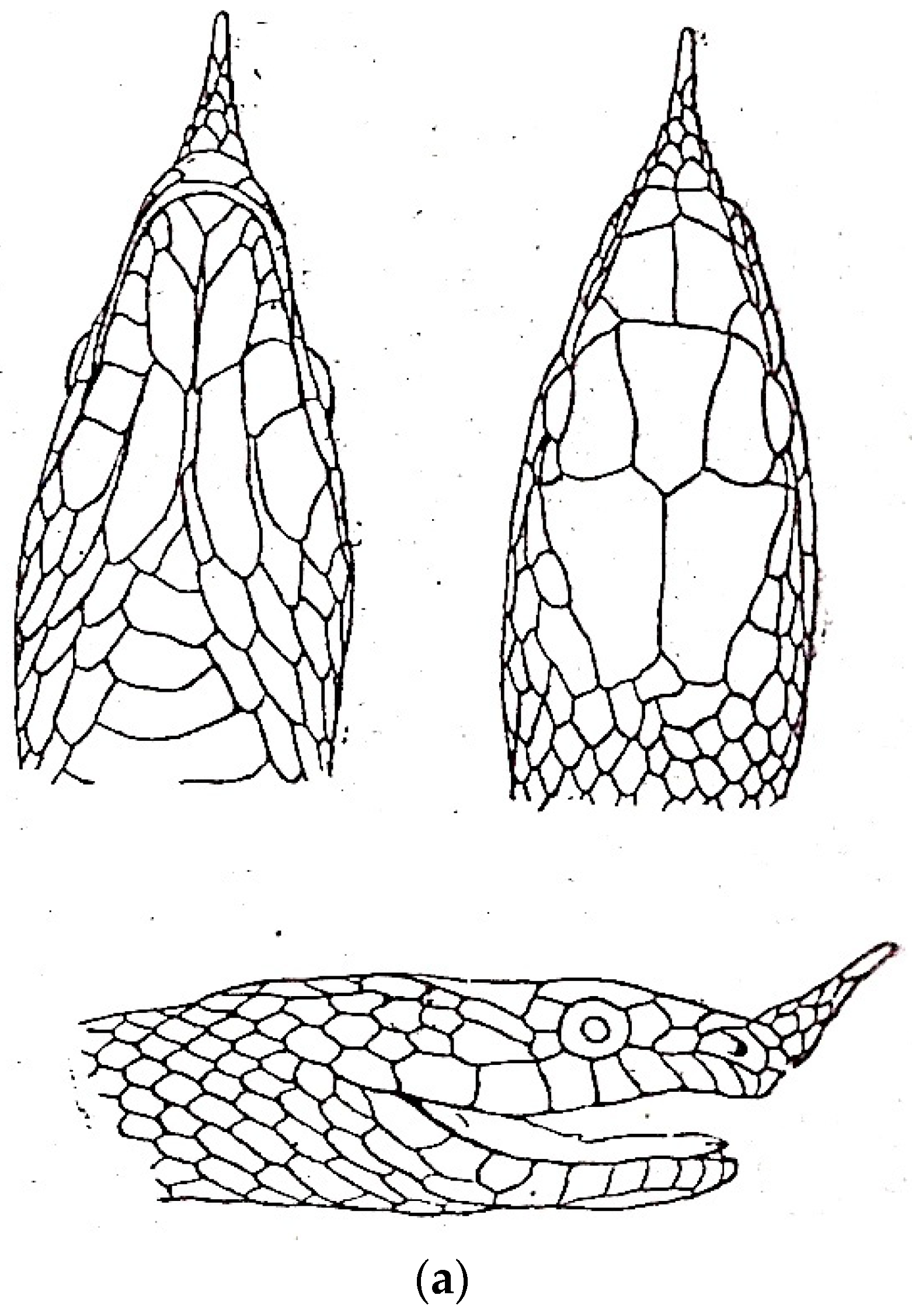

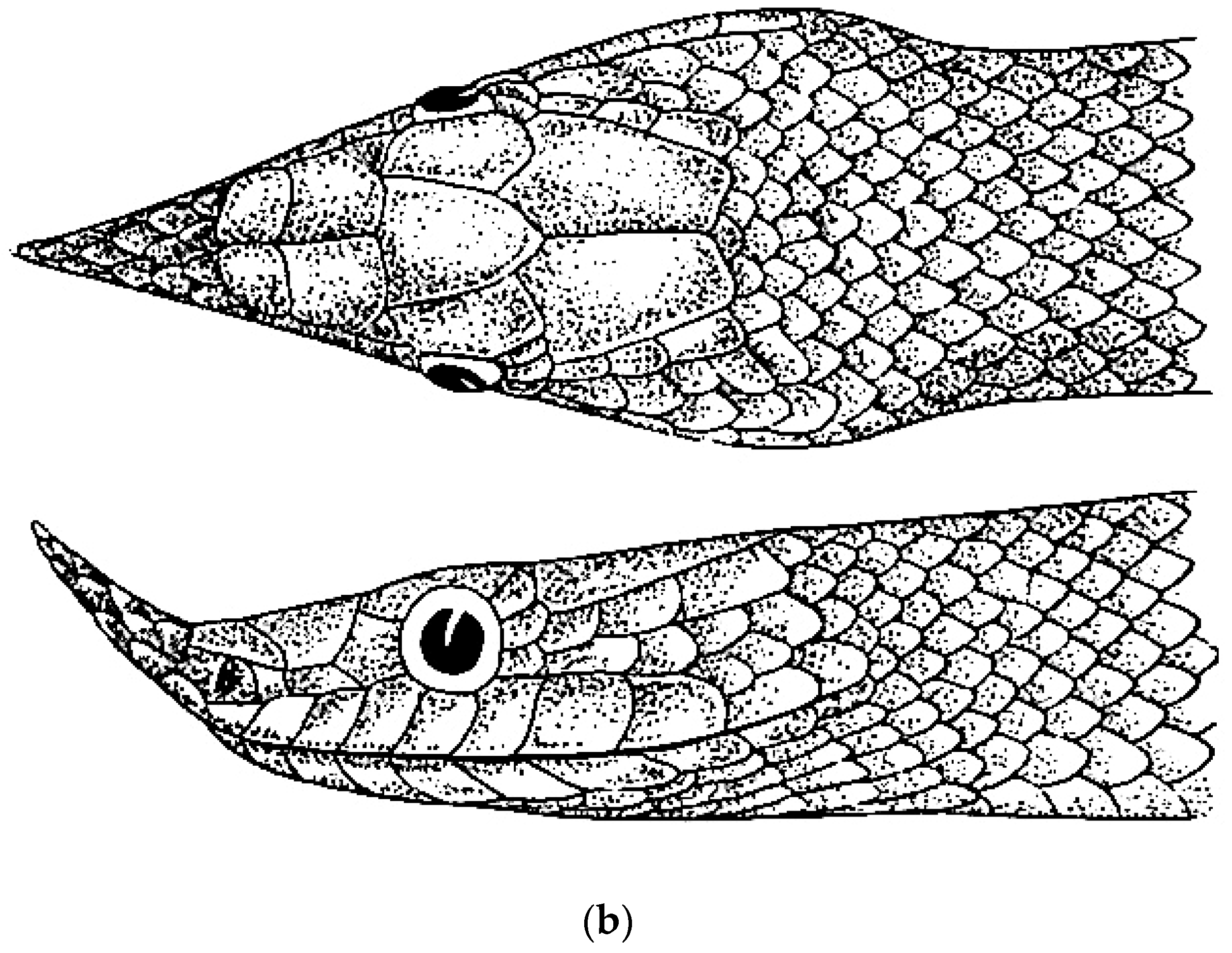

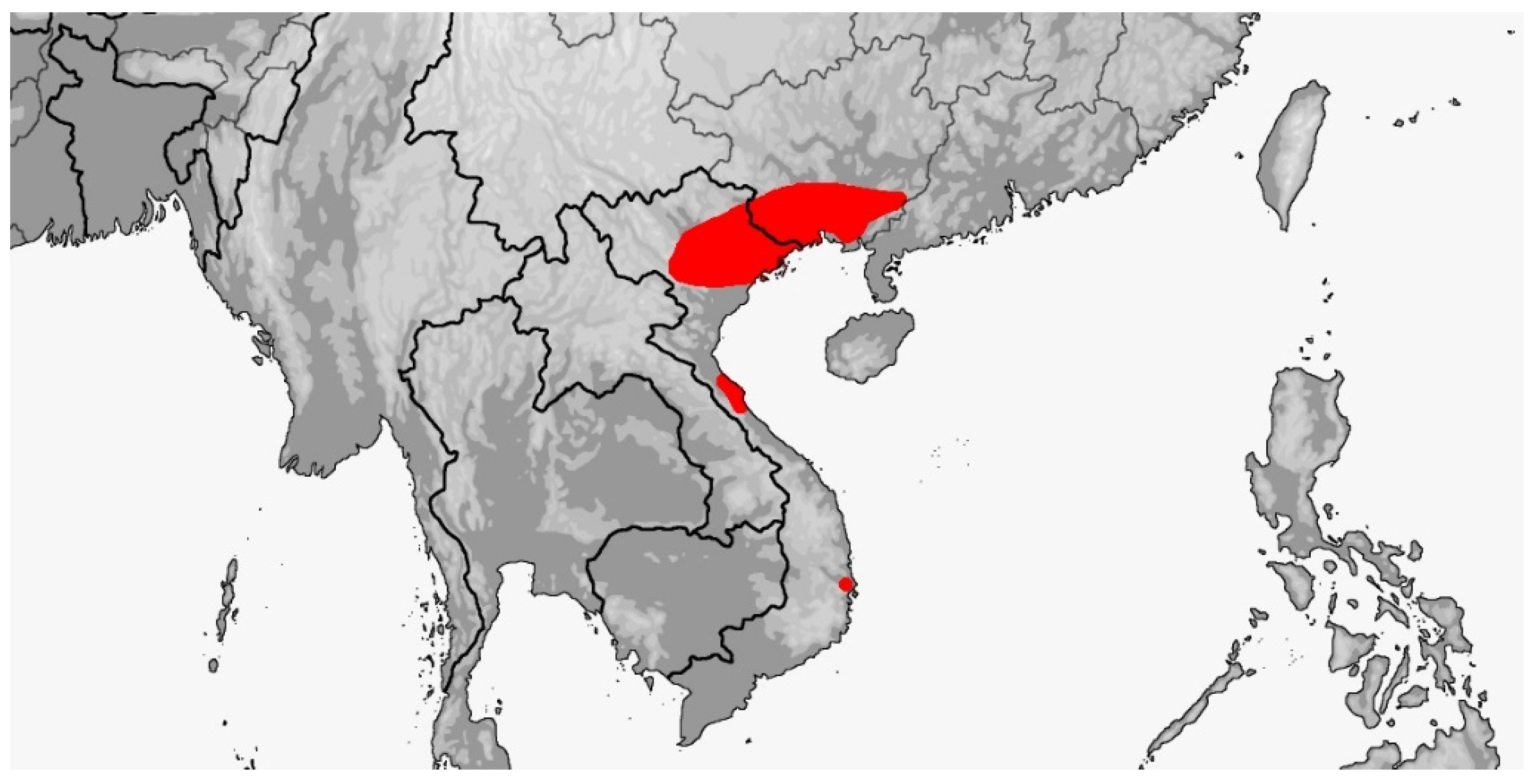

3.4.1. Rhynchophis boulengeri

3.4.2. Rhynchophis hainanensis

3.5. Verdigrophis gen. nov.

3.5.1. Verdigrophis coeruleus Comb. nov.

3.5.2. Verdigrophis prasinus Comb. nov.

3.6. Gonyosomini Tribe nov.

3.7. Gonyosomini Key

- 1a.

- Rostral appendage present, subtriangular frontal, and internasal length equals width 2 (Rhynchophis).

- 1b.

- Rostral appendage absent, frontal not subtriangular, and internasal length not equal to width 3.

- 2a.

- One elongated loreal, pre- and postocular bars present, ventrolateral light stripe present on tail, and temporals usually 2 + 3 + 3: Rhynchophis boulengeri.

- 2b.

- Two normal loreals, pre- and postocular bars absent, ventrolateral light stripe absent on tail, and temporals usually 2 + 2+ 3: Rhynchophis hainanensis.

- 3a.

- Midbody scale rows 23–27; scales entirely smooth; preocular contacts frontal; umbilicus–vent interval >14% total ventrals; tail uniformly black, red, or brown; and tracheal lung present 4 (Gonyosoma).

- 3b.

- Midbody scale rows 17–19, scales partly/feebly keeled, preocular not contacting frontal, umbilicus–vent interval < 14% total ventrals, tail uniformly green or black with orange rings, and tracheal lung absent 5.

- 4a.

- Tail red to brown; ventrolateral light stripe broad; iris green, blue, or gray; subcaudals light with median zigzag line; and usually two anterior temporals: Gonyosoma oxycephalum.

- 4b.

- Tail black, ventrolateral light stripe absent or narrow, iris yellow or orange, subcaudals uniformly black, and usually one anterior temporal: Gonyosoma janseni.

- 5a.

- Loreal shield absent, supralabials eight, internasal length greater than width, posterior genials longer than anterior genials, iris yellow, ontogenetic color change from juveniles to adult, and frontal narrow with parallel sides: Rhadinophis frenatus.

- 5b.

- Loreal shield present, supralabials nine, internasal width greater than length, posterior genials not longer than anterior genials, iris not yellow, no ontogenetic color change from juveniles to adult, and frontal broad with tapered sides 6.

- 6a.

- Head orange, dorsum multicolored with orange and black rings posteriorly, ventrals > 230, ventrolateral light stripe absent on body and tail, and anterior genials longer than posterior genials: Gonyophis margaritatus.

- 6b.

- Head green or blue, ventrals < 225, spotted ventrolateral stripe present on body, and anterior genials equal in length to posterior genials 7 (Verdigrophis).

- 7a.

- Cloacal shield entire, ventrolateral stripe yellow, iris greenish yellow or olive, mouth pink, and tongue reddish brown: Verdigrophis prasinus.

- 7b.

- Cloacal shield divided, ventrolateral stripe white, iris blue or greenish blue, mouth grey, and tongue brownish yellow: Verdigrophis coeruleus.

4. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Material Examined

References

- Schulz, K.-D. A Monograph of the Colubrid Snakes of the Genus Elaphe Fitzinger; Koeltz Scientific Books: Prague, Czech Republic, 1996; pp. 1–439. [Google Scholar]

- Midtgaard, R. RepFocus—A Survey of the Reptiles of the World. 2023. Available online: www.repfocus.dk (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Günther, A.C.L.G. The Reptiles of British India; Robert Hardwicke: London, UK, 1864; pp. 1–452. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, C.H. The Reptiles of China; American Museum of Natural History: New York, NY, USA, 1935; pp. 1–604. [Google Scholar]

- Boulenger, G.A. Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum (Natural History); Volume II, Containing the Conclusion of the Colubridae Aglyphae; British Museum (Natural History): London, UK, 1894; pp. 1–382. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, H.G. A taxonomic study of the ratsnakes. VI. Validation of the genera Gonyosoma Wagler and Elaphe Fitzinger. Copeia 1958, 1958, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A. Fauna of British India. Reptilia and Amphibia; Volume Ophidia; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1943; pp. 1–583. [Google Scholar]

- Staszko, R.; Walls, J.G. Rat Snakes: A Hobbyist’s Guide to Elaphe and Kin; T.F.H. Publications: Neptune City, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; McKelvy, A.D.; Grismer, L.L.; Matsui, M.; Nishikawa, K.; Burbrink, F.T. The phylogenetic position and taxonomic status of the rainbow tree snake Gonyophis margaritatus (Peters, 1871) (Squamata: Colubridae). Zootaxa 2014, 3881, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocquard, F. Notes herpetologiques. Bull. Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat. 1897, 3, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.E. Descriptions of some undescribed species of reptiles collected by Dr. Joseph Hooker, in the Khasia Mountains, E Bengal and Sikkim, Himalaya. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1853, 12, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, W.C.H. Über neue Reptilien aus Ostafrica und Sarawak (Borneo), vorzüglich aus der Sammlung des Hrn. Marquis, J. Doria zu Genua. Monats. König. Akad. Wissen. 1871, 1871, 566–581. [Google Scholar]

- Boie, F. Bemerkungen über Merrem’s Versuch eines Systems der Amphibien. 1te Lieferung: Ophidier. Isis v. Oken 1827, 20, 508–566. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth, E. Notices and descriptions of various reptiles, new or little known. J. Asiatic Soc. Bengal (Nat. Hist.) 1858, 23, 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- de Bleeker, P. Gonyosoma jansenii Blkr., eene nieuwe slang van Manado. Natuurk. Tijds. Nederl. Indië 1858, 16, 242. [Google Scholar]

- Burbrink, F.T.; Lawson, R. How and when did Old World ratsnakes disperse into the New World? Mol. Phylo. Evol. 2007, 43, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, D.; Ribeiro-Júnior, M.A.; Simonov, E.; Soltys, K.; Meiri, S. A new, rare, small-ranged, and endangered mountain snake of the genus Elaphe from the southern Levant. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.-X.; Yang, S.-J.; Savitzky, A.H.; Cheng, Y.-Q.; Mori, A.; Ding, L.; Rao, D.-Q.; Wang, Q. Cryptic diversity and phylogeography of the Rhabdophis nuchalis group (Squamata: Colubridae). Mol. Phylo. Evol. 2022, 166, 107325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratakis, M.; Koutmanis, I.; Ilgaz, C.; Jablonski, D.; Kukushkin, O.V.; Crnobrnja-Isailovic, J.; Carretero, M.A.; Liuzzi, C.; Kumlutas, Y.; Lymberakis, P.; et al. Evolutionary divergence of the smooth snake (Serpentes, Colubridae): The role of the Balkans and Anatolia. Zool. Scripta 2022, 51, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, D.; Mendes, J.; Carranza, S.; Harris, D.J. Evolution, biogeography and systematics of the western Palearctic Zamenis snakes. Zool. Scripta 2018, 47, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, M.E.; Karns, D.R.; Voris, H.K.; Brock, C.D.; Stuart, B.L. Phylogeny, evolutionary history, and biogeography of Oriental-Australian rear-fanged water snakes (Colubroidea: Homalopsidae) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Mol. Phylo. Evol. 2008, 46, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McVay, J.D.; Flores-Villela, O.; Carstens, B. Diversification of North American natricine snakes. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 2015, 116, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guicking, D.; Lawson, R.; Joger, U.; Wink, M. Evolution and phylogeny of the genus Natrix (Serpentes: Colubridae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2006, 87, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, H.M.; Branch, W.R.; Tolley, K.A. Snakes on an African plain: The radiation of Crotaphopeltis and Philothamnus into open habitat (Serpentes: Colubridae). Peer J. 2021, 9, e11728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadollahvandmiandoab, R.; Koroiva, R.; Bashirichelkasari, N.; Mesquita, D.O. Phylogenetic relationships and divergence times of the poorly known genus Spalerosophis (Serpentes: Colubridae). Organ. Diver. Evol. 2023, 23, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hou, M.; Lwin, Y.H.; Wang, Q.; Rao, D. A new species of Gonyosoma Wagler, 1828 (Serpentes, Colubridae), previously confused with G. prasinum (Blyth, 1854). Evol. Syst. 2021, 5, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Burbrink, F.T.; Chen, J.-M.; Hou, M.; Zhu, Y.-W.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.-C. A new snake species of the genus Gonyosoma Wagler, 1828 (Serpentes: Colubridae) from Hainan Island, China. Zool. Res. 2021, 42, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalremsanga, H.T.; Decemson, H.; Vabeiryureilai, M.; Muansanga, L.; Biakzuala, L. Contributions to the morphology and molecular phylogenetics of Gonyosoma prasinum (Blyth, 1854) (Reptilia: Squamata: Colubridae) from Mizoram, India. Hamadryad 2022, 39, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Boulenger, G.A. On new or little-known Indian and Malayan reptiles and batrachians. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1891, 8, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vogt, T. Beiträge zur Fauna Sinica. Zur Reptilien- und Amphibienfauna Südchinas. Archiv Natur. 1922, 88, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Vences, M.; Guayasamin, J.M.; Miralles, A.; de la Riva, I. To name or not to name: Criteria to promote economy of chance in Linnean classification schemes. Zootaxa 2013, 3636, 201–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.; Teynié, A.; Vogel, G. The snakes of Laos; Edition Chimaira; NHBS GmbH: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–960. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, W.C.H. Über eine neue von Hrn. Dr. A.B. Meyer auf Luzon entdeckte Art von Eidechsen (Lygosoma (Hinulia) leucospilos) und eine von demselben in Nordcelebes gefundene neue Schlangengattung (Allophis nigricaudus). Monats. König. Akad. 1872, 1872, 684–687. [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij, N. The Reptiles of the Indo-Australian Archipelago. II. Ophidia; E.J. Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1917; pp. 1–334. [Google Scholar]

- Tweedie, M.W.F. The Snakes of Malaya, 3rd ed.; Singapore National Printers: Singapore, 1983; pp. 1–167. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, K.-D.; Gumprecht, A. Undercover in the rainforest canopy: The rainbow tree snake Gonyophis margaritatus. In Old World Ratsnakes; Schulz, K.-D., Ed.; Bushmaster Publications: Berg, Germany, 2013; pp. 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Stuebing, R.B.; Inger, R.F.; Lardner, B. A Field Guide to the Snakes of Borneo, 2nd ed.; Natural History Publications: Borneo, Malaysia, 2014; pp. 1–310. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, T. A Guide to Snakes of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore; Natural History Publications: Borneo, Malaysia, 2020; pp. 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Das, I. A Field Guide to the Reptiles of South-East Asia; New Holland Publishers: London, UK, 2010; pp. 1–376. [Google Scholar]

- Malkmus, R.; Manthey, U.; Vogel, G.; Hoffmann, P.; Kosuch, J. Amphibians & Reptiles of Mount Kinabalu (North Borneo); A.R.G. Gantner Verlag: Ruggell, Liechtenstein, 2002; pp. 1–424. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, D.; Jenkins, H.; Das, I.; Auliya, M.; Inger, R.F.; Lilley, R. Gonyophis margaritatus; E.T192044A2032534; IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E.H. The serpents of Thailand and adjacent waters. Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull. 1965, 45, 609–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Tepedelen, K.; Smith, H.M. Natural history notes: Serpentes: Elaphe janseni (Celebes black-tailed ratsnake). Maximum size. Herp. Rev. 1998, 29, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Fesser, R. Forty years of husbandry and breeding of Old World ratsnakes—A summary. In Old World Ratsnakes; Schulz, K.-D., Ed.; Bushmaster Publications: Berg, Germany, 2013; pp. 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- de Lang, R.; Vogel, G. The Snakes of Sulawesi; Edition Chimaira; NHBS GmbH: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2005; pp. 1–312. [Google Scholar]

- Rusli, N.; Gillespie, G. Gonyosoma jansenii; E.T104839453A104853990; IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty, R.; Saw, I. Beobachtungen an Gonyosoma oxycephalum (Boie, 1827) beim erbeuten von Höhlenfledertieren auf den Andamanen, Indien. Sauria 2014, 36, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nutaphand, W. Snakes in Thailand; Amarin Printing & Publishing Company: Bangkok, Thailand, 2001; pp. 1–320. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Wagler, J.G. Auszüge aus seinem Systema Amphibiorum. Isis Von Oken 1828, 21, 740–744. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, H. Essai sur la Physionomie des Serpens; I. Partie Générale. II. Partie Descriptive. Atlas; Arnz & Comp.: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1837; pp. 1–251+606. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.E. Description of three new genera and species of snakes. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1849, 4, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, E. Report upon the Reptilia of the North Pacific Exploring Expedition, under the command of Capt. John Rogers, U.S.N. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. USA 1861, 12, 480–510. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, F. Neue Schlangen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien. Ann. Naturhist. Mus. 1923, 36, 160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, F. Neue oder wenig bekannte Schlangen aus dem Wiener naturhistorischen Staatsmuseum (Teil.). Sitz. Akad. Wiss. (Math. Nat.) 1925, 134, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, F. Neue oder wenig bekannte Schlangen aus dem Wiener naturhistorischen Staatsmuseum (III. Teil). Sitz. Akad. Wiss. (Math. Nat.) 1926, 135, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E.H. The Snakes of the Philippine Islands; Bureau of Printing: Manila, Philippines, 1922; pp. 1–312. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, D.T. A new color variation of Gonyosoma oxycephalum from central Java. The Snake 1987, 19, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lillywhite, H.B.; Ellis, T.M. Extrapulmonary air sacs in an arboreal snake (abstract). Amer. Zool. 1991, 31, 38A. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, V. The lungs of snakes. In Biology of the Reptilia; Gans, C., Gaunt, A.S., Eds.; Volume 19 (Morphology G); Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles: Athens, GA, USA, 1998; pp. 93–295. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, J.L. A Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Bali; Krieger Publishing Company: Malabar, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 1–138. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, R.; Captain, A. Snakes of India: The Field Guide; Draco Books: Chennai, India, 2004; pp. 1–479. [Google Scholar]

- Pickersgill, S.; Meek, R. Husbandry notes on the Asian rat snake Gonyosoma oxycephala. Brit. Herp. Soc. Bull. 1988, 23, 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Grismer, L.L. Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of the Seribuat Archipelago (Peninsular Malaysia): A Field Guide; Edition Chimaira; NHBS GmbH: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–239. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M.J.; Hoover, M.F.; Chanhome, L.; Thirakhupt, K. The Snakes of Thailand; Chulalongkorn University Museum of Natural History: Bangkok, Thailand, 2012; pp. 1–845. [Google Scholar]

- Wogan, G.; Vogel, G.; Neang, T.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Demegillo, A.; Diesmos, A.C.; Gonzalez, J.C. Gonyosoma oxycephalum; E.T183196A1732988; IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann, S.; Norval, G.; Mao, J.J. A gravid Indonesian Red-tailed Green Ratsnake (Gonyosoma oxycephalum [Boie 1827]) in the pet trade. IRCF Rept. Amph. 2015, 22, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lang, R. The Snakes of Java, Bali and Surrounding Islands; Edition Chimaira; NHBS GmbH: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–435. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, E.-M.; Huang, M.-H.; Zong, Y. Fauna Sinica. Reptilia Vol. 3, Squamata: Serpentes; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1998; pp. 1–522. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K.P. New reptiles and a new salamander from China. Amer. Mus. Novit. 1925, 157, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.-C.; Huang, M.-H.; Ho, S.-S.; Wei, K.-C. New records of snakes from Chekiang. Acta Zool. Sin. 1958, 10, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.C. Fauna of India and Adjacent Countries. Reptilia. Volume-III (Serpentes); Zoological Survey of India: Kolkata, India, 2007; pp. 1–410. [Google Scholar]

- You, C.-W.; Li, S.-W.; Lau, A. Ratsnakes of Taiwan: An annotated photographic review. In Old World Ratsnakes; Schulz, K.-D., Ed.; Bushmaster Publications: Berg, Germany, 2013; pp. 369–384. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, V.; Williams, K.L.; Boundy, J. Snakes of the World: A Catalogue of Living and Extinct Snakes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 1–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Wangyal, J.T.; Das, I. A Guide to the Reptiles of Bhutan; Bhutan Ecological Society: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2021; pp. 1–109. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Lau, M. Gonyosoma frenatum; E.T191929A2016603; IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Messenger, K.R. The Asian Ratsnakes and Kin of Greater China; KDP Publishing: Nanjing, China, 2021; pp. 1–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bourret, R. Notes herpétologiques sur l’Indochine française. Bull. Gén. Instr. Publ. 1934, 14, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Obst, F.J.; Richter, K.; Jacob, U. The Completely Illustrated Atlas of Reptiles and Amphibians for the Terrarium; T.F.H. Publications: Neptune City, FL, USA, 1988; pp. 1–831. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, T.H. Preliminary report of reptiles from Yaoshan, Kwangsi, China. Bull. Depart. Biol. Sun Yatsen Univ. 1931, 11, 1–154. [Google Scholar]

- Brachtel, N. Das Portrait: Rhynchophis boulengeri Mocquard. Sauria 1998, 20, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, K.-D.; Ryabov, S.; Wang, X. Contribution to the knowledge of the Oriental rhino ratsnake, Rhynchophis boulengeri Mocquard. In Old World Ratsnakes; Schulz, K.-D., Ed.; Bushmaster Publications: Berg, Germany, 2013; pp. 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Kane, D.; Le, M.V.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hoang, H.V.; McCormack, T.E.M.; Tapley, B.; Nguyen, S.N. The southernmost distribution of the rhinocercos snake, Gonyosoma boulengeri (Mocquard, 1897) (Reptilia, Squamata, Colubridae), in Vietnam. Check List 2020, 16, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, D.; Gill, I.; Harding, L.; Capon, J.; Franklin, M.; Servini, F.; Tapley, B.; Michaels, C.J. Captive husbandry and breeding of Gonyosoma boulengeri. Herp. Bull. 2017, 139, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Orlov, N.L. Rare snakes of the mountainous forests on northern Indochina. Russ. J. Herp. 1995, 2, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Orlov, N.L.; Ryabov, S.A.; Schulz, K.D. Eine seltene Natter aus Nordvietnam, Rhynchophis boulengeri Mocquard, 1897 (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae). Sauria 1999, 21, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Devisch, F. Rhynchophis boulengeri. Vietnamese long-nosed snake, rhino rat snake. Litt. Serpent. 2010, 30, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.T.; Stenke, R.; Nguyen, H.X.; Ziegler, T. The terrestrial reptile fauna of the Biosphere Reserve Cat Ba Archipelago, Hai Phong, Vietnam. Bonn. Zool. Monogr. 2011, 57, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, D.Q.; Lau, M. Rhynchophis boulengeri; E.T190628A1955324; IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, G. Ein Fall von Kannibalismus bei Gonyosoma boulengeri (Mocquard, 1897), mit Anmerkungen zur Inkubation im Terrarium. Sauria 2015, 37, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schleich, H.H.; Kästle, W. Amphibians and Reptiles of Nepal: Biology, Systematics, Field Guide; A.R.G. Gantner Verlag: Ruggell, Liechtenstein, 2002; pp. 1–1201. [Google Scholar]

- David, P.; Campbell, P.D.; Deuti, K.; Hauser, S.; Luu, V.Q.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Orlov, N.; Pauwels, O.S.G.; Scheinberg, L.; Sethy, P.G.S.; et al. On the distribution of Gonyosoma prasinum (Blyth, 1854) and Gonyosoma coeruleum Liu, Hou, Ye Htet Lwin, Wang & Rao, 2021, with a note on the status of Gonyosoma gramineum Günther, 1864 (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae). Zootaxa 2022, 5154, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grossmann, W. Elaphe prasina (Blyth). Sauria 2002, 24, 573–576. [Google Scholar]

- Wogan, G.; Grismer, L.L.; Chan-Ard, T. Rhadinophis prasina; E.T192082A2037579; IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilieva, A.B.; Galoyan, E.A.; Poyarkov, N.A.; Geisssler, P. A Photographic Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of the Lowland Monsoon Forests of Southern Vietnam; Edition Chimaira; NHBS GmbH: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–324. [Google Scholar]

- Holman, J.A. Pleistocene Amphibians and Reptiles in Britain and Europe; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 1–284. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, M. Miocene snakes of Eurasia: A review of the evolution of snake communities. In The Origin and Early Evolutionary History of Snakes; Gower, D.J., Zaher, H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, A.; McKelvy, A.D.; Grismer, L.L.; Bell, C.D.; Lailvaux, S.P. A species-level phylogeny of extant snakes with description of a new colubrid subfamily and genus. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Elev | ASR | MSR | PSR | C | SR | KR | V | C.S. | SC | L | SL | SLO | Pst | ||

| margaritatus | 0–2000 | 19–21 | 19 | 15–17 | k + s | I–III/VI | IV/VII-Vert | 230–249 | D | 108–130 | 1S | 9 (8,10) | 3–5/4–6/5–7 (5–6) | 2 | ||

| jansenii | 100–1000 | 21–23 | 23–25 | (13) | S | All | None | 245–257 | D | 130–140 | 1E | 9–10 | 5–7 (6–7) | 2 | ||

| oxycephalum | 20–1400 | 23–27 | 23–25 (27) | 15–17 | S | All | None | 229–263 | D | 120–157 | 1E (0) | 9–11 (7,8) | 4–5/5–6/6–7/4–6 5–7/6–8 | 2 | ||

| frenatus | 170–2800 | 19 (21) | 19 (17) | 17 | k + s | I–VIII | PV + V | 198–235 | D | 108–149 | 0 | 8 (9) | 3–5/4–6 | 2 | ||

| boulengeri | 0–2000 | 19 | 19 (17,18) | 15 (13) | k + s | I–VI | VII-V | 207–227 | D | 101–133 | 1E | 9 (10) | 4–6/5–7 | 2 (3) | ||

| hainanenesis | 80–900 | 19 | 19 | 15 (13) | k + s | VL | MD | 216–221 | D | 122–133 | 2S | 9 | 4–6 | 2 | ||

| coeruleus | 250–1650 | 19 (20) | 19 (15,17) | 15 (13,17) | k + s | I–IV/VI | V/VII–Vert | 181–224 | D | 88–128 | 1S | 9 (8,10) | 4–6 (3–5) | 2 | ||

| prasinus | 75–2560 | 19 (17,21) | 19 (17) | 15 (13,17) | k + s | I–V/VI | VI/VII–Vert | 186–209 | E | 91–116 | 1S (0) | 9 (8) | 4–6 (4–5) | 2 | ||

| Species | AT | MT | PT | IL | AG | LOA | RTL | UVI | R.A. | P-F | Fr | IN | Max. | VLTS | J.C. | Eggs |

| margaritatus | 2 | 2–3 | 2–3 | 10–12 | 5 | 424–1943 | 22.6–33.3 | 11.8–13.3 | No | No | B/T | W = 1.5L | 20–23 | No | MC | ? |

| jansenii | 1 (2) | 2–3 | 3 | 11–13 | 1–5 | 120–2374 | 23.7–31.0 | 16.7 | No | Yes | M/T | L = W | ? | No | Gr | 2–9 |

| oxycephalum | 2 (1,3) | 2 (4,5) | 3 | 12–15 | 1–5 (6,7) | 170–2400 | 20.9–27.7 | 14.2–18.7 | No | Yes | M/T | L = 2W | 20–25 | No | Gr | 2–12 |

| frenatus | 2 (1,3) | 2–3 | 2–3 (4) | 9–11 | 1–5/6 | 120–1475 | 22.0–32.5 | 12.5–14.1 | No | No | N/P | L > W | 19–25 | Yes | Gy/O/B | 6–12 |

| boulengeri | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 3 | 10–11 | 1–5 (6) | 170–1630 | 20.6–30.2 | 13.1–13.7 | Yes | Yes | S | L = W | 16–22 | Yes | Gy/B | 5–17 |

| hainanenesis | 2 | 2 | 3 | 10–12 | 1–5 | 150–1229 | 22.0–32.5 | ? | Yes | Yes | S | L = W | ? | No | Gy | 6 |

| coeruleus | 1–2 | 2 (1,3) | 2–3 | 9–11 | 1–5 | 200–1192 | 19.4–27.5 | 13.7 | No | No | B/T | L = W | 20–21 | No | Gr | 3–11 |

| prasinus | 1–2 | 1–2 (3) | 2 (3) | 9–10 (12) | 1–5 (6) | 150–1355 | 19.4–27.7 | 14.4 | No | No | B/T | L = W | 19–23 | No | Gr | 3–14 |

| Genus | MSR | C | KR | Lor | SL | P/F | Fr | IN | Gen | RA | Head | GD | DP | Tail | Iris | T.L. | MI | O | L.L. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonyophis | 19 | k + s | 7–13 | 1 | 9 | 0 | B/T | W > L | A > P | 0 | O | 0 | R | B/O | B/R/Br | 0 | P | 0 | 1.9 |

| Gonyosoma | 23–25 | S | 0 | 1 | 9–11 | + | M/T | L > W | P > A | 0 | R/G/Gr/B | + | U | B/R/Br | Y/O/G/Bl | + | P | 0 | 5.6–7.5 |

| Rhadinophis | 19 | k + s | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0 | N/P | L > W | P > A | 0 | G | + | U | G | Y | 0 | P/Pu | + | 1.3 |

| Rhynchophis | 19 | k + s | 3 | 1–2 | 9 | + | S | L = W | P > A | + | G | + | U | G | Br | 0 | P | + | 0.8 |

| Verdigrophis | 19 | k + s | 5–11 | 1 | 9 | 0 | B/T | W > L | P = A | 0 | Bl/G | + | U | G | Bl/G | 0 | G/P | 0 | 1.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wallach, V.; Midtgaard, R.; Hsiao, E. Revalidation of the Arboreal Asian Snake Genera Gonyophis Boulenger, 1891; Rhynchophis Mocquard, 1897; and Rhadinophis Vogt, 1922, with Description of a New Genus and Tribe (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae). Diversity 2024, 16, 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16090576

Wallach V, Midtgaard R, Hsiao E. Revalidation of the Arboreal Asian Snake Genera Gonyophis Boulenger, 1891; Rhynchophis Mocquard, 1897; and Rhadinophis Vogt, 1922, with Description of a New Genus and Tribe (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae). Diversity. 2024; 16(9):576. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16090576

Chicago/Turabian StyleWallach, Van, Rune Midtgaard, and Emma Hsiao. 2024. "Revalidation of the Arboreal Asian Snake Genera Gonyophis Boulenger, 1891; Rhynchophis Mocquard, 1897; and Rhadinophis Vogt, 1922, with Description of a New Genus and Tribe (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae)" Diversity 16, no. 9: 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16090576

APA StyleWallach, V., Midtgaard, R., & Hsiao, E. (2024). Revalidation of the Arboreal Asian Snake Genera Gonyophis Boulenger, 1891; Rhynchophis Mocquard, 1897; and Rhadinophis Vogt, 1922, with Description of a New Genus and Tribe (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae). Diversity, 16(9), 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16090576