Yoke-Type Elasto-Magnetic Sensor-Based Tension Force Monitoring Method for Enhancement of Field Applicability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Principle of Elasto-Magnetic Sensor

2.1. Reverse Magnetostrictive Effect for Detecting Tension Force Changes

2.2. Faraday’s Law of Electromagnetic Induction for Flux Density Measurement

2.3. Principle of Solenoid-Type E/M Sensor

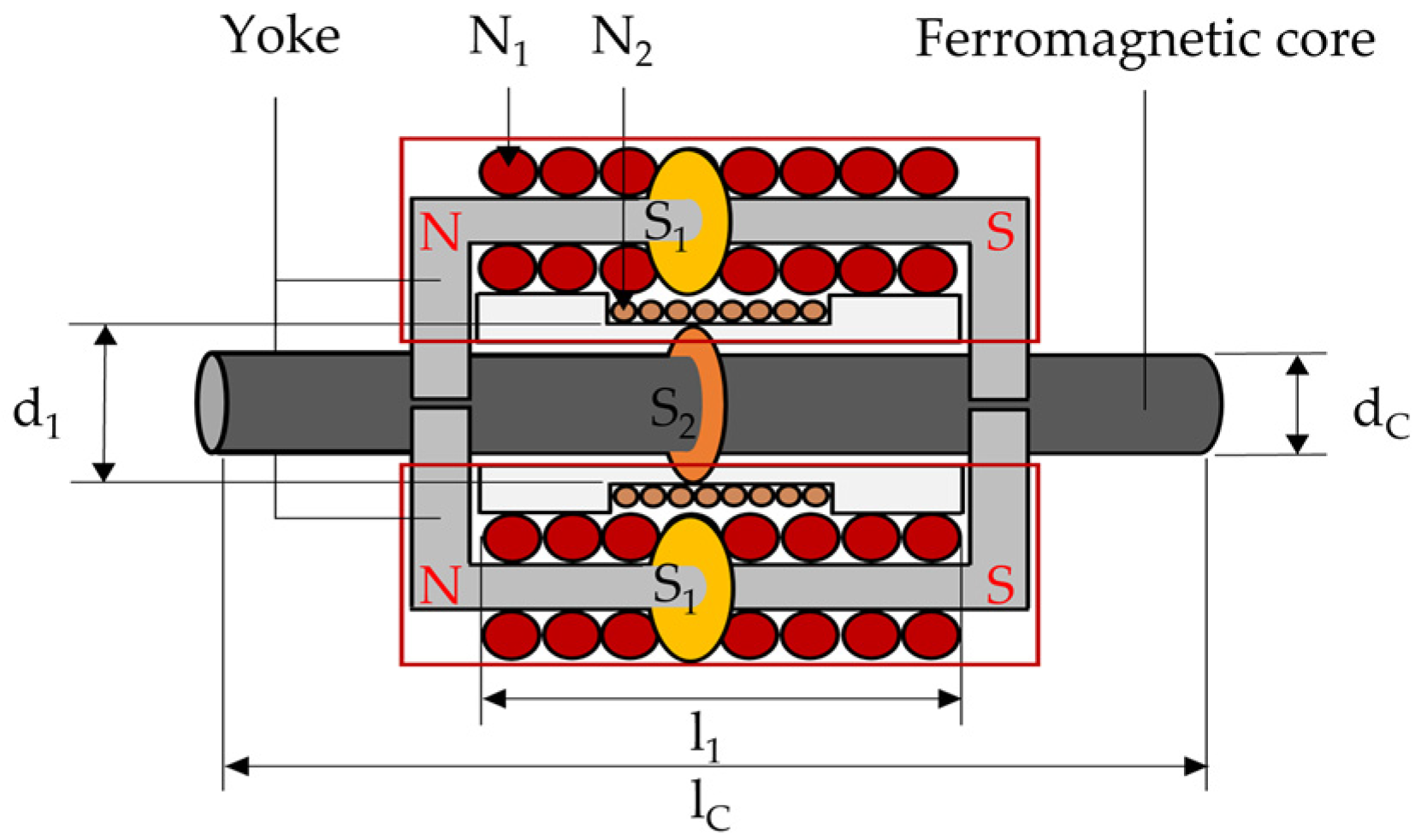

2.4. Principle of Yoke-Type E/M Sensor

2.5. Wireless Communication Data Collection Equipment for E/M Sensor Signal Acquisition

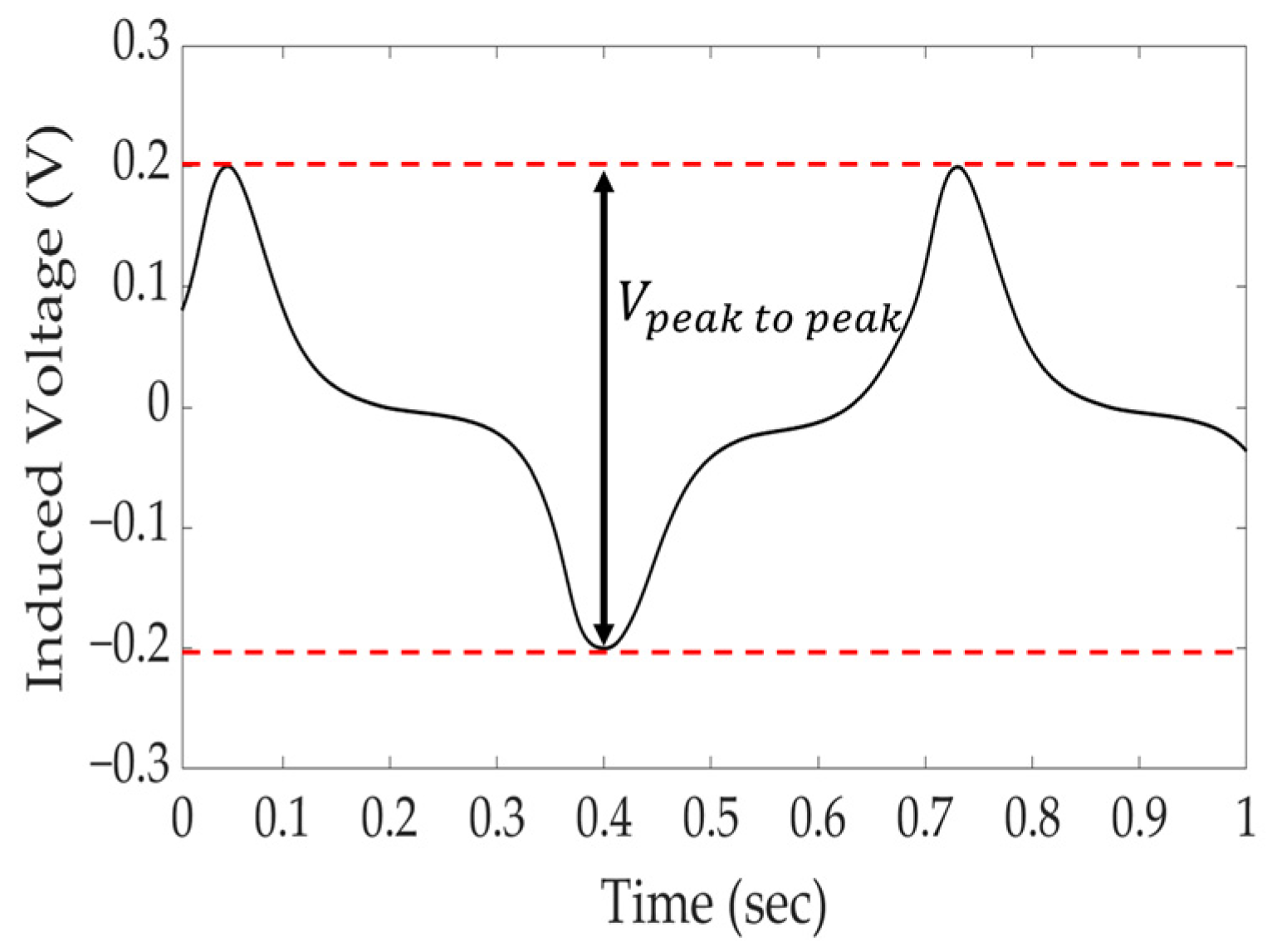

2.6. Derivation of Peak-to-Peak Value for Quantification of Induced Voltage Signal

3. Development of Yoke-Type E/M Sensor

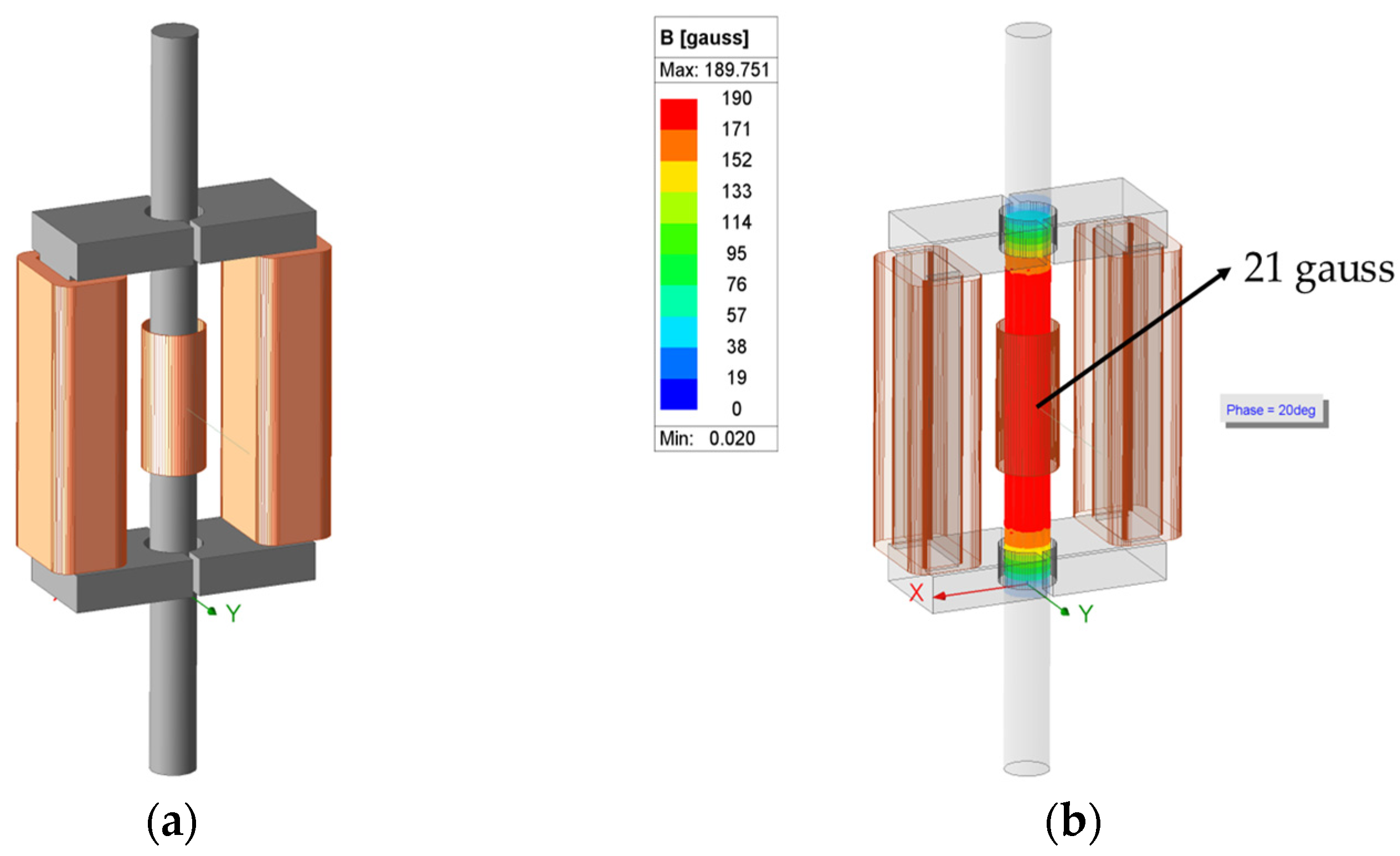

3.1. Simulation for Numerical Design of E/M Sensor

3.2. Fabrication of Yoke-Type E/M Sensor for Measuring Tension Force

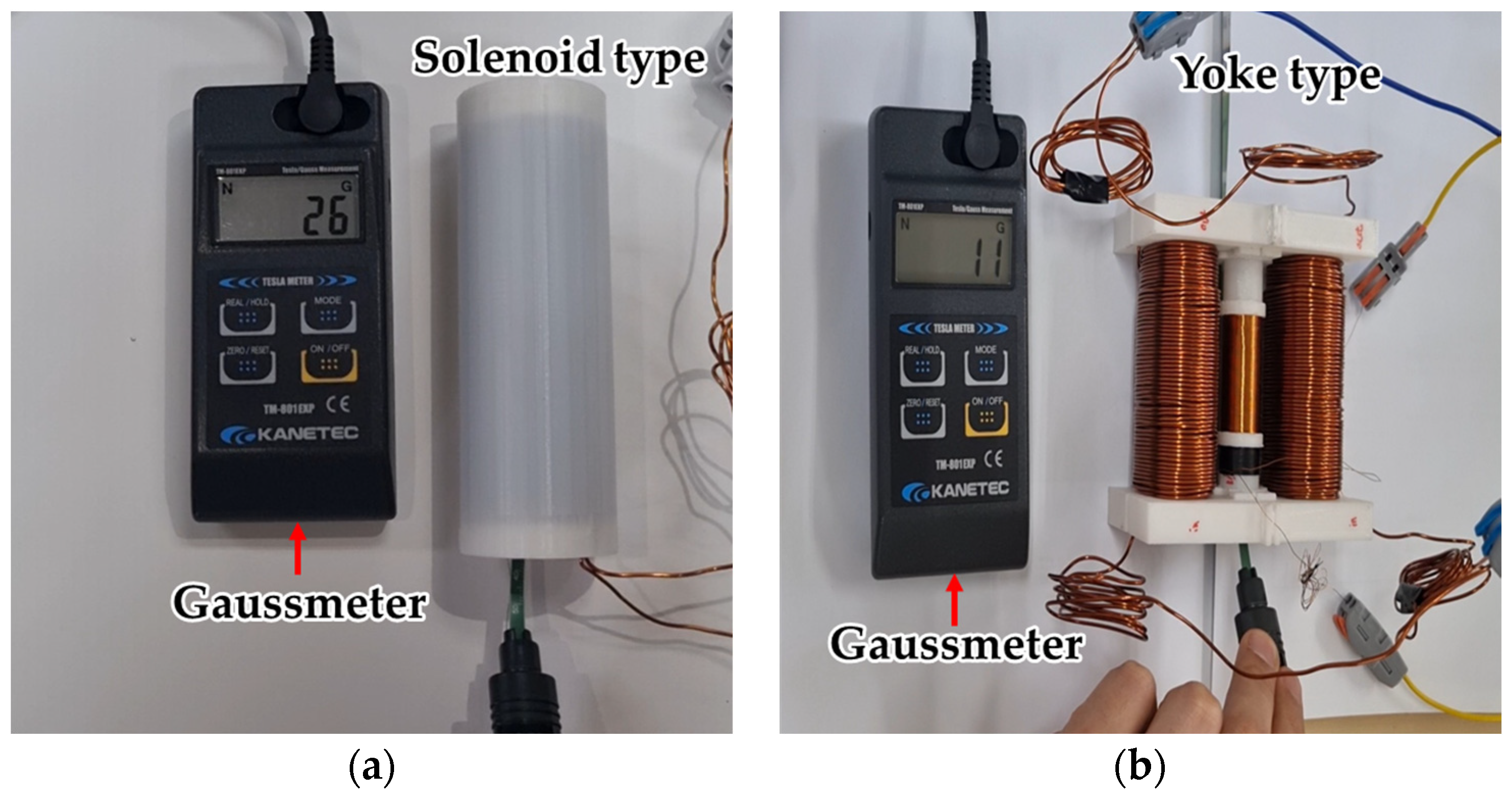

3.3. Magnetic Field Measurement of Solenoid-Type and Yoke-Type Sensors Using a Gaussmeter

4. Experimental Studies for Tension Force Estimation Using E/M Sensor

Experimental Setup and Progress for Tension Force Measurement

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

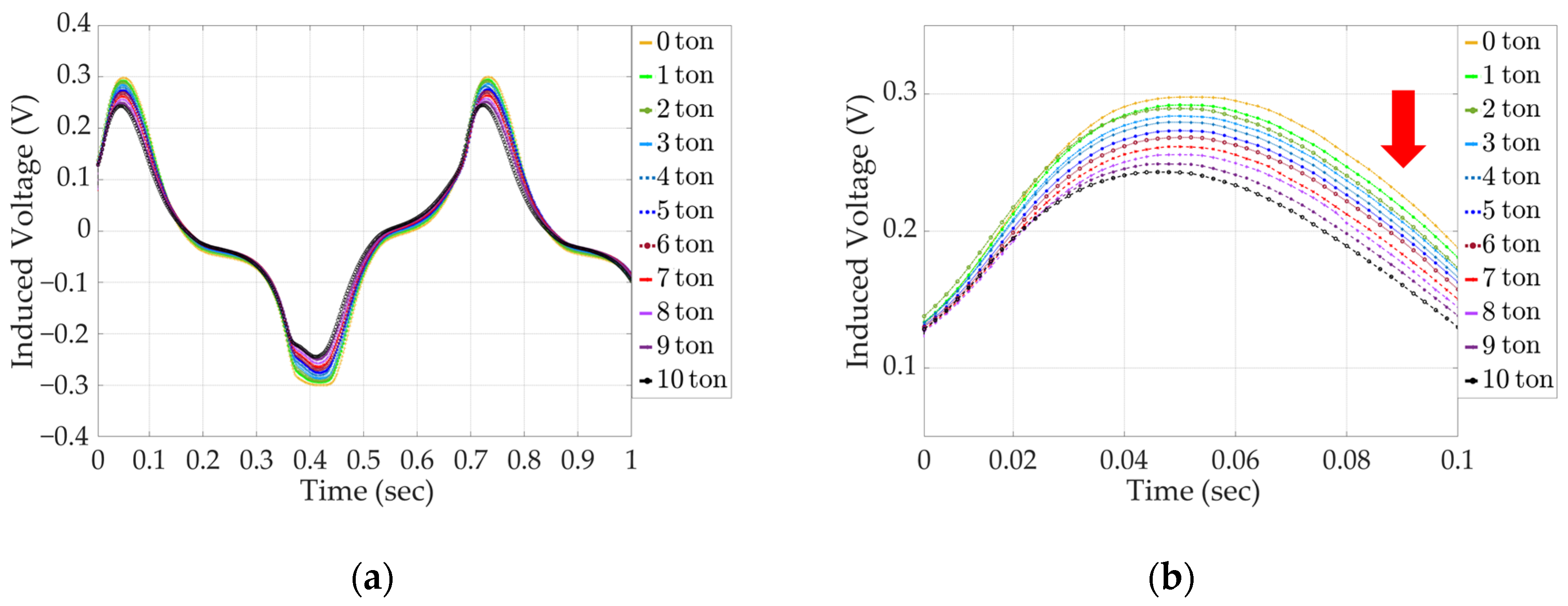

5.1. The Induced Voltage Signal of the Secondary Coil with Increasing Tension Results (Solenoid-Type E/M Sensor)

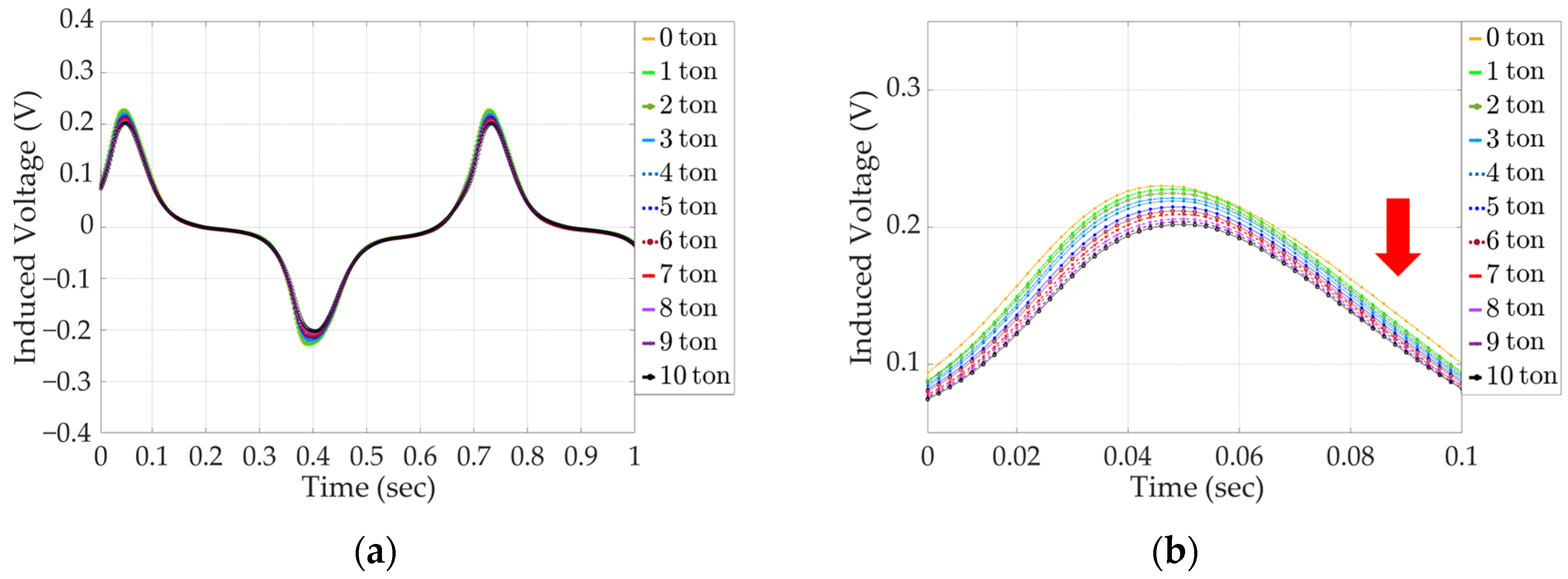

5.2. The Induced Voltage Signal of the Secondary Coil with Increasing Tension Results (Yoke-Type E/M Sensor)

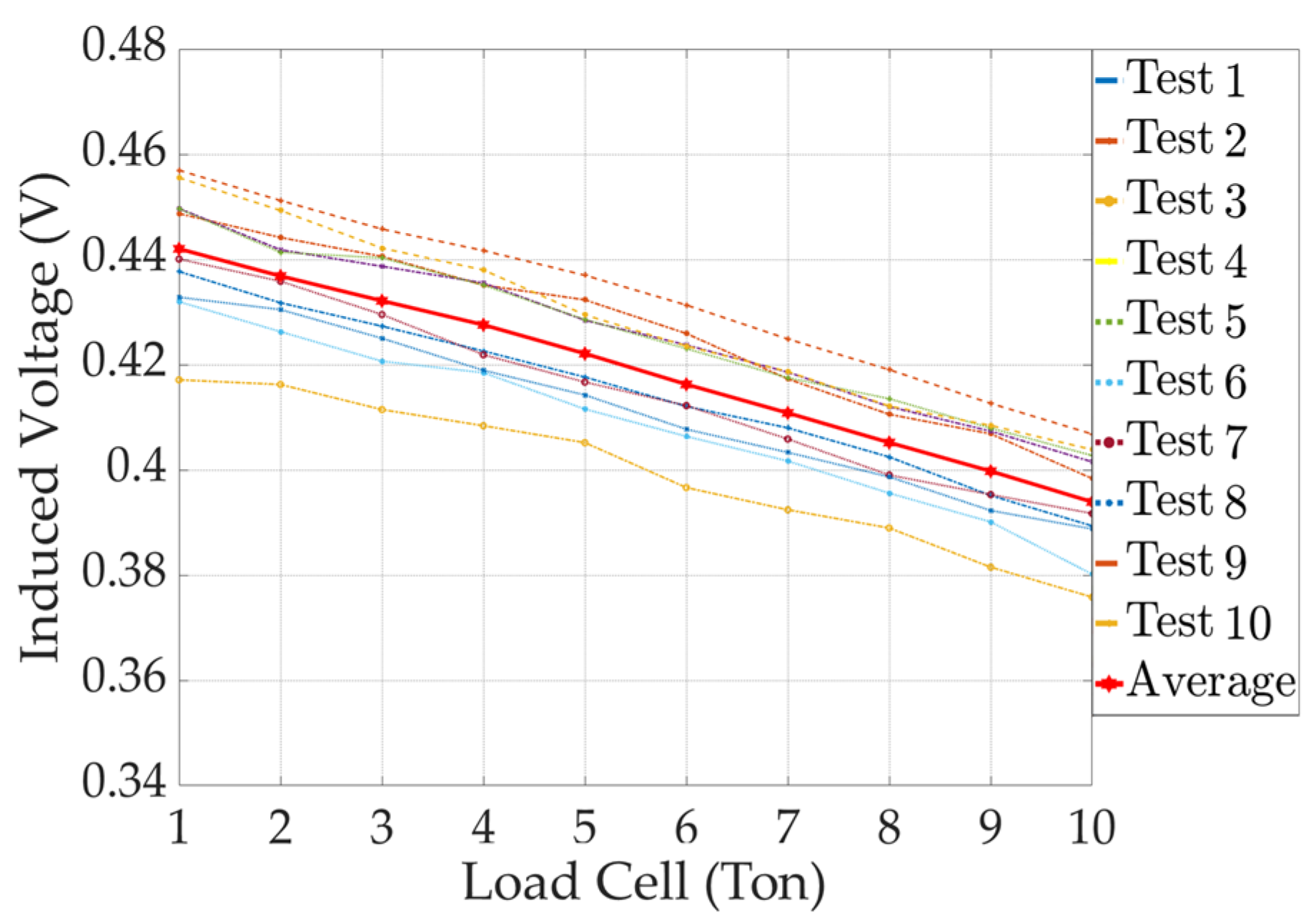

5.3. Peak-to-Peak Results with Increasing Tension (Solenoid-Type E/M Sensor)

5.4. Peak-to-Peak Results with Increasing Tension (Yoke-Type E/M Sensor)

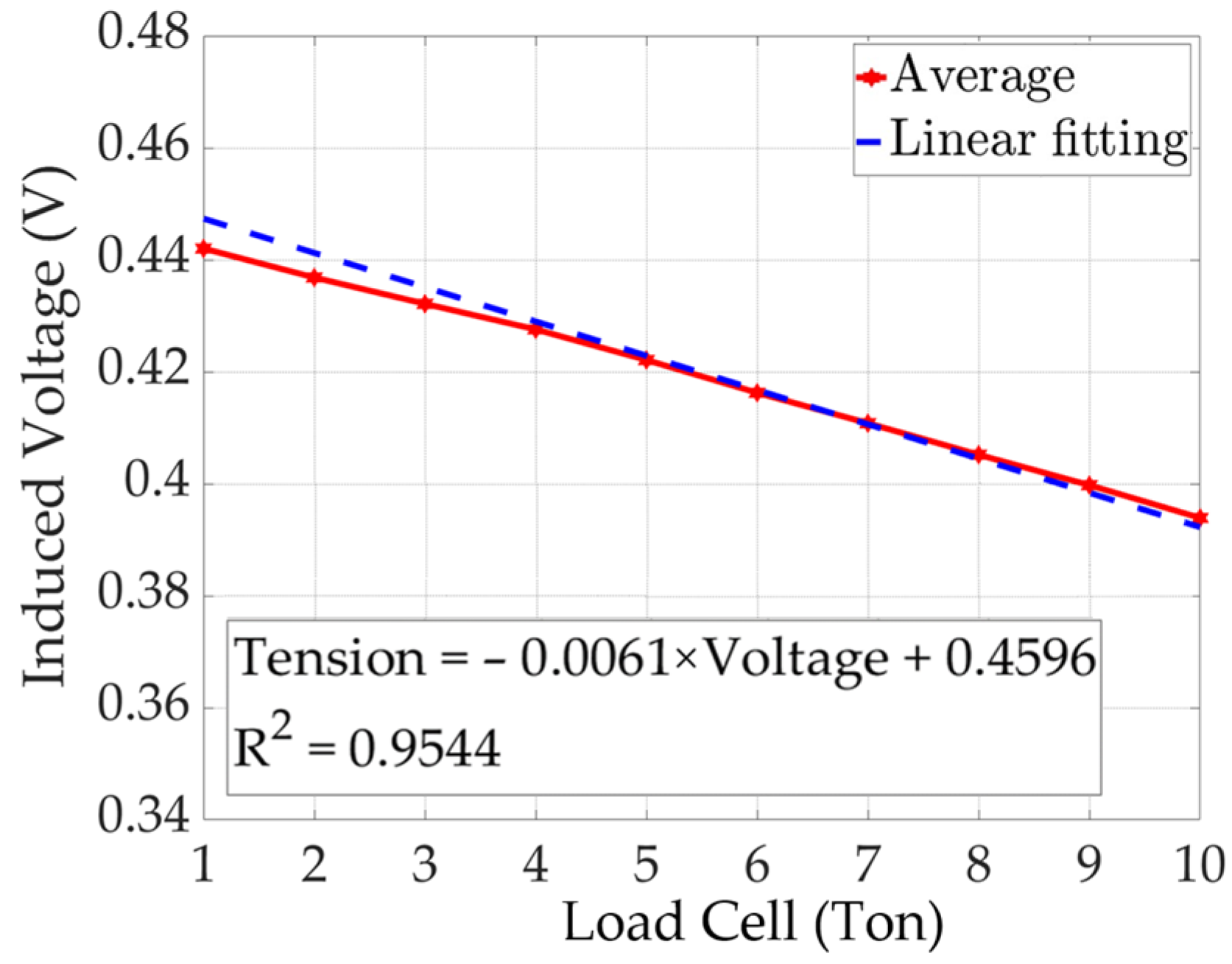

5.5. The Linear Regression Analysis Results of Peak-to-Peak Value of Induced Voltages (Solenoid-Type E/M Sensor)

5.6. The Linear Regression Analysis Results of Peak-to-Peak Value of Induced Voltages (Yoke-Type E/M Sensor)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations & Nomenclature

| PSC | Prestressed Concrete |

| MFL | Magnetic Flux Leakage |

| FBG | Fiber Bragg Grating |

| E/M | Elasto Magnetic |

| SFT | Suspended Floating Tunnel |

| DAQ | Data Acquisition |

| FE | Finite Element |

| B | Magnetic flux density [T] |

| H | Magnetic field intensity [A/m] |

| λ | Strain |

| N | Number of turns in the coil [Turn] |

| S | Internal cross-sectional area of the coil [] |

| d | Diameter of the coil [m] |

| l | Length of the coil [m] |

| Φ | Magnetic flux [T·] |

| Vacuum permeability [kg·m·s/] | |

| I | Current applied to the coil [A] |

References

- Wang, J.H.-C. Mechanobiology of tendon. J. Biomech. 2006, 39, 1563–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniele, M.; Nicola, S.; Andrea, O.; Rui, P.; Matteo, M.; Gian, M. Numerical study on the collapse of the Morandi bridge. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2020, 34, 04020044. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Chiew, Y.; Lu, J.; Lai, J.; Lin, Y. Houfeng bridge failure in Taiwan. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2012, 138, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jung, H.; Yoon, S.; Park, J. Dynamic Response Measurement and Cable Tension Estimation Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, J.; Lee, E.; Park, S. Field Application of a Cable NDT System for Cable-Stayed Bridge Using MFL Sensors Integrated Climbing Robot. J. Korean Soc. Nondestruct. Test. 2014, 34, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.; Li, J.; Park, J.; Cho, S.; Spencer, J.R.; Jung, H. A wireless smart sensor network for automated monitoring of cable tension. Smart Mater. Struct. 2014, 23, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Bao, Y. Measurement of cable forces for automated monitoring of engineering structures using fiber optic sensors: A review. Autom. Constr. 2021, 126, 103687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Park, Y.; Yang, I.; Kim, Y. FBG sensors encapsulated into 7-wire steel strand for tension monitoring of a prestressing tendon. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2012, 15, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zeng, J.; Chen, B.; Lu, R.; Zhu, Y.; Qi, L.; Chen, X. Spacecraft Segment Damage Identification Method Based on Fiber Optic Strain Difference Field Reconstruction and Norm Calculation. Sensors 2023, 23, 8822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thies, P.; Johanning, L.; Harnois, V.; Smith, H.; Parish, D. Mooring line fatigue damage evaluation for floating marine energy converters: Field measurements and prediction. Renew. Energy 2014, 63, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawski, L.; Ostachowicz, W.; Opoka, S.; Mieloszyk, M.; Majewska, K. Practical application of monitoring system based on optical sensors for marine constructions. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 518, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, J.; Joung, Y. Long-term reliability evaluation of nuclear containments with tendon force degradation. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2013, 265, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosevic, A. Magnetoelastic Method of Stress Measurement in Steel. Smart Struct. 1999, 65, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Koontz, S.; Lloyd, G. Magnetoelastic permeability measurement for stress monitoring in steel tendons and cables. Proc. SPIE-Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2000, 3995, 492–500. [Google Scholar]

- Sumitro, S.; Kurokawa, S.; Shimano, K.; Wang, M. Monitoring based maintenance utilizing actual stress sensory technology. Smart Mater. Struct. 2005, 14, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Y. Application of EM stress sensors in large steel cables. In Sensing Issues Civil Struct Health Monitoring; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Kim, J.; Park, J.; Kim, W.; Park, S. Verification of tensile force estimation method for temporary steel rods of FCM bridges based on area of magnetic hysteresis curve using embedded elasto-magnetic sensor. Sensors 2022, 22, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.; Park, S. Development of embedded EM sensors for estimating tensile forces of PSC girder bridges. Sensors 2017, 17, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joule, J. On the electric origin of the heat of combustion. Philos. Mag. 1842, 20, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. Magnetostriction and magnetomechanical effects. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1955, 18, 184–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. Magnetostriction curves of polycrystalline ferromagnetics. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1958, 72, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belahcen, A.; Peusssa, T.; Singh, D.; Rasilo, P. Computation of the inverse magnetostriction and its application in mechanical stress sensing. In Proceedings of the 9th IET International Conference on Computation in Electromagnetics (CEM 2014), London, UK, 31 March–1 April 2014; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Davino, D.; Giustiniani, A.; Visone, C. Design and test of a stress-dependent compensator for magnetostrictive actuators. IEEE Trans. Magnet. 2010, 46, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiles, D. Introduction to Magnetism and Magnetic Materials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zuza, K.; Guisasola, J.; Michelini, M.; Santi, L. Rethinking Faraday’s law for teaching motional electromotive force. Eur. J. Phys. 2012, 33, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Park, S.; Lim, H.; Baek, S.; Kim, D.; Yoon, S. Analysis of the Optimal Location of Wearable Biosensor Arrays for Individual Combat System Considering Both Monitoring Accuracy and Operational Robustness. J. Korea Inst. Mil. Sci. Technol. 2019, 22, 287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Oh, J.; Kim, Y. Design and Control of Multi-Plate MR Clutch Featuring Friction and Magnetic Field Control Modes. Sensors 2022, 22, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, A.; Abudhahir, A.; Daniel, J. Development of magnetic flux leakage measuring system for detection of defect in small diameter steam generator tube. Measurement 2017, 95, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.; Park, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.; Yoon, H.; Park, S. Experimental Study for Nondestructive Evaluation of Embedded Tendons in Ground Anchors Using an Elasto-Magnetic Sensor: Verification Through Numerical Finite Element Simulations. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 26055–26066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaikhli, T.; Ahmad, B.; Al-Taweel, M. The implementations and applications of ampere’s law to the theory of electromagnetic fields. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 28, 515–525. [Google Scholar]

- Puaypung, W.; Rakkapao, S. A low-cost Arduino microcontroller for measuring magnetic fields in a solenoid. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1144, 012125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coil | Material | Diameter (mm) | Voltage (V) | Resistance (Ohm) | Inductance | Number of Turns | Winding Length (mm) | Number of Layers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Copper | 1.2 | 1.75 | 10 | 260 | 15.6 | 4 | |

| 2nd | 0.2 | 0 | 0.36 | 194 | 7.6 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.-J.; Kyung, S.-B.; Kim, J.-W. Yoke-Type Elasto-Magnetic Sensor-Based Tension Force Monitoring Method for Enhancement of Field Applicability. Sensors 2024, 24, 3369. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113369

Lee H-J, Kyung S-B, Kim J-W. Yoke-Type Elasto-Magnetic Sensor-Based Tension Force Monitoring Method for Enhancement of Field Applicability. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3369. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113369

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ho-Jun, Sae-Byeok Kyung, and Ju-Won Kim. 2024. "Yoke-Type Elasto-Magnetic Sensor-Based Tension Force Monitoring Method for Enhancement of Field Applicability" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3369. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113369