Abstract

Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum spp., Pedaliaceae) is one of the best-documented phytomedicines. Its mode of action is largely elucidated, and its efficacy and excellent safety profile have been demonstrated in a long list of clinical investigations. The author conducted a bibliographic review which not only included peer-reviewed papers published in scientific journals but also a vast amount of grey literature, such as theses and reports initiated by governmental as well as non-governmental organizations, thus allowing for a more holistic presentation of the available evidence. Close to 700 sources published over the course of two centuries were identified, confirmed, and cataloged. The purpose of the review is three-fold: to trace the historical milestones in devil’s claw becoming a modern herbal medicine, to point out gaps in the seemingly all-encompassing body of research, and to provide the reader with a reliable and comprehensive bibliography. The review covers aspects of ethnobotany, taxonomy, history of product development and commercialization, chemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, as well as clinical efficacy and safety. It is concluded that three areas stand out in need of further investigation. The taxonomical assessment of the genus is outdated and lacking. A revision is needed to account for intra- and inter-specific, geographical, and chemo-taxonomical variation, including variation in composition. Further research is needed to conclusively elucidate the active compound(s). Confounded by early substitution, intermixture, and blending, it has yet to be demonstrated beyond a reasonable doubt that both (or all) Harpagophytum spp. are equally (and interchangeably) safe and efficacious in clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Devil’s claw is the collective name of plants from the genus Harpagophytum (Pedaliaceae). The latter includes two species, H. procumbens (Burch.) DC. ex Meisn. and H. zeyheri Decne., currently divided into five subspecies with introgression reported from overlapping habitats [1,2]. The secondary root tubers of devil’s claw are used in botanical drugs and supplements and are exported from Southern Africa, mainly Namibia. Entrepreneurial spirit, colonialism, and the absence of regulatory barriers drove the commercialization of devil’s claw in a fashion similar to that of other medicinal plants from Southern Africa, such as Umckaloabo (Pelargonium sidoides) [3], rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) and honeybush (Cyclopia spp.) [4], buchu (Agathosma betulina) [5], cape aloe (Aloe ferox) [6], uzara (Xysmalobium undulatum) [7], and to some extent, hoodia (Hoodia gordonii) [8], among others [9]. From the 1960s onward, products quickly gained popularity, initially in Germany, then France, and by the mid-1980s, all over the developed world. This led to an increase in demand and consequently harvesting pressure in the countries of origin, to the point that devil’s claw was briefly considered to be listed on CITES appendix II [10]. However, ongoing efforts to introduce good harvesting practices and cultivation attempts helped supply to become more sustainable.

Once harvested, botanical differentiation between species and subspecies is virtually impossible, and it can safely be assumed that since the 1970s, the product of commerce is one or the other and often of mixed origin [11,12,13,14]. Thus, current official compendia do not distinguish between the two botanical sources of devil’s claw but require compliance in terms of contents of the marker compound harpagoside, a cinnamoylated iridoid glucoside. The primary medicinal uses of devil’s claw are the management of arthritis, pain, and dyspepsia [15,16]. An impressive number of clinical trials, the earlier being mostly observational, the more recent randomized, placebo-controlled studies—albeit being of variable quality—indicate clinical efficacy and safety [17]. However, whether harpagoside is more than a just marker, but also the (only) active compound, remains to be demonstrated. Consequently, superiority of H. procumbens over H. zeyheri cannot be derived merely from harpagoside content [18]. Lower levels of harpagoside do not necessarily translate to lower levels of total iridoids, and phytochemically distinct extracts from H. procumbens and H. zeyheri have shown similar in vivo analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties [19].

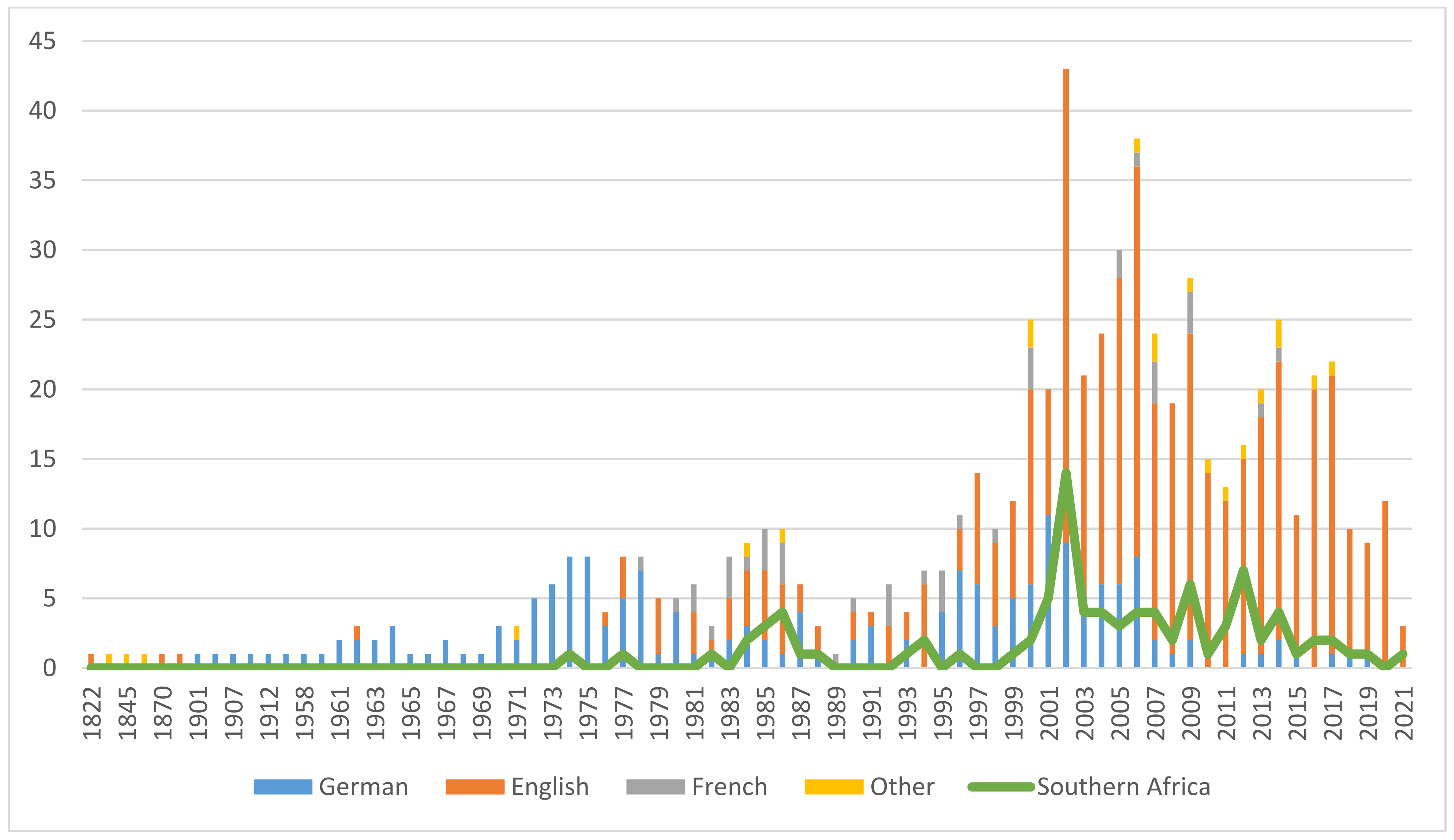

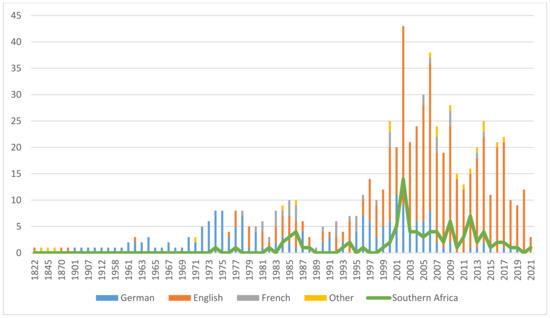

The vast body of evidence presented here—over a period of 55 years, about one general review per year was published in the scientific literature [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80], not counting reviews specific to clinical efficacy (see Section 12.1.)—makes devil’s claw one of the best-researched botanicals. Figure 1 illustrates the growing and sustained research interest. The 694 included publications were grouped by language, which yielded a perspective on how research interest spread geographically over time. Despite English becoming the lingua franca of science toward the end of the 20th century, a trend is clearly noticeable—from Germany to France to the rest of the world—and confirmed by research, trade, and availability and popularity of pharmaceutical products. An interesting discrepancy reveals itself when comparing the total with the research output of the region of origin. Nonetheless, knowledge gaps concerning species interchangeability remain to be closed, the elucidation of which is one purpose of this review. It is hoped that the assembly of this extensive bibliography will stimulate further research of this interesting genus of medicinal plants.

Figure 1.

Publications on Harpagophytum spp., 1822–2021 (colors indicate publication language/origin of research).

2. Materials and Methods

Multiple searches were conducted in the PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases with the following keywords and combinations thereof: “Harpagophytum, harpagophyton, devil(’)s claw, Teufelskralle, grapple plant, sengaparile, garra-do-diabo, griffe du diable, (h)arpagoside, taxonomy, nomenclature, ethnobotany, traditional use, ecology, cultivation, sustainability, economy, trade, CITES, chemistry, biochemistry, compounds, pre-clinical, pharmacology, clinical, RCT, safety, toxicology, veterinary, review”. Union catalogues were also searched. The search was limited to scientific literature, and popular magazines and compendia were excluded. Also excluded were articles which only mentioned Harpagophytum without elaboration. Further excluded were reports on compounds present in Harpagophytum, that were derived from other sources (e.g., harpagoside from Scrophularia spp.).

Reference sections of selected publications were searched manually. Academic theses were retrieved primarily via the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE). Patents were retrieved from the European, US, and international (WIPO) patent office databases.

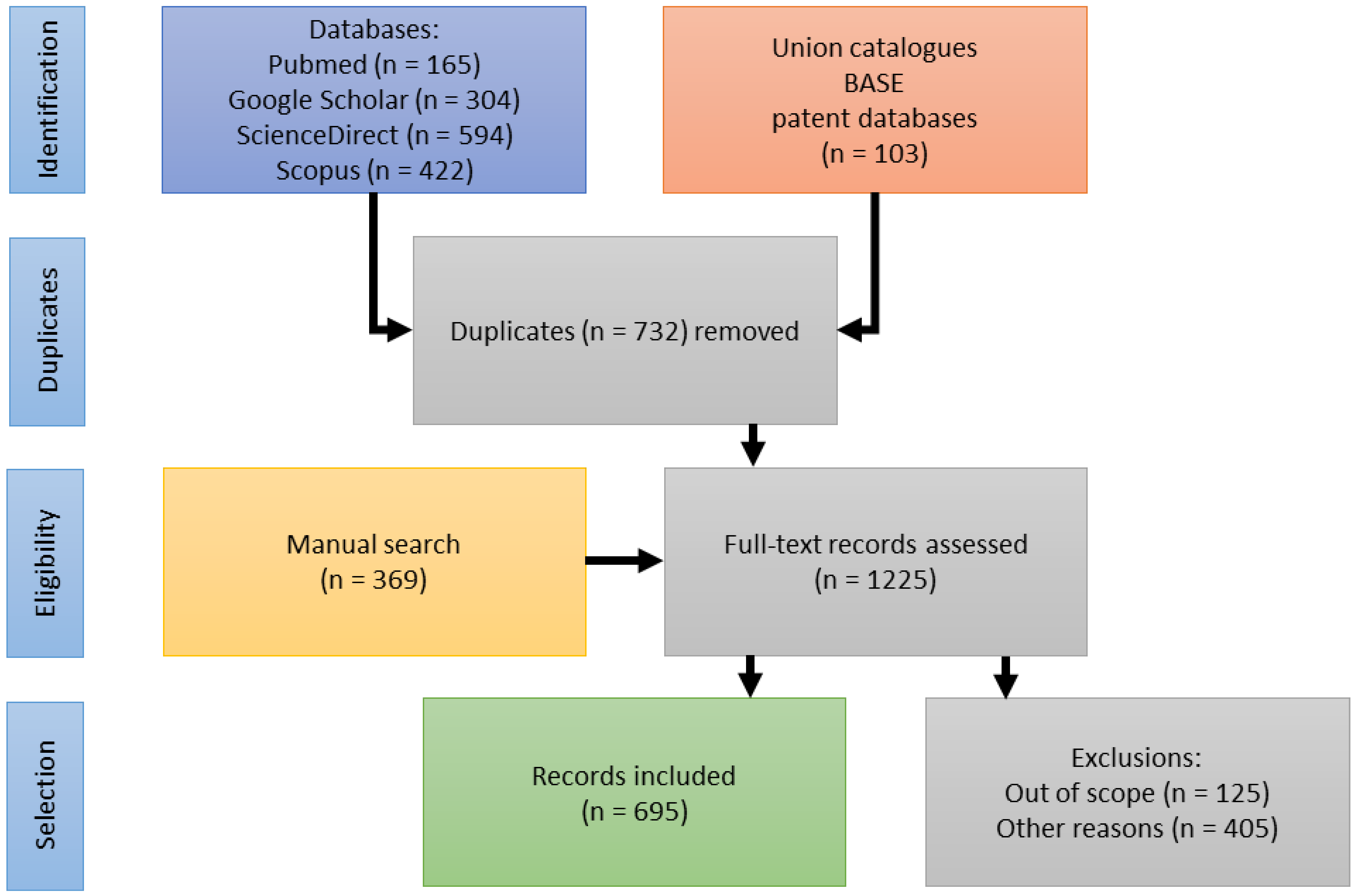

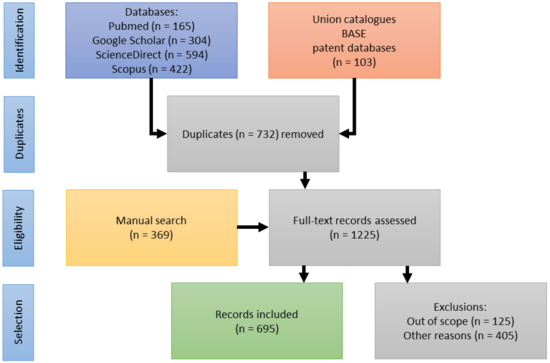

A substantial body of publications (125) was identified addressing aspects of ecology, stakeholders’ livelihoods, efforts in capacity building, as well as access-benefit-sharing (ABS) and its legislation. They are included in the publication statistics (see Figure 1). In reviewing the pharmaceutical history of devil’s claw, however, these topics appear out of scope and will be reviewed in a separate publication. Figure 2 illustrates the selection process.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the reference identification, screening and inclusion.

3. Nomenclature

3.1. Taxonomy

The genus Harpagophytum was first described as Uncaria Burch. by Burchell in his Travels in the interior of southern Africa (1822) [81]. However, he was apparently unaware that Uncaria had already been used by Schreber for a genus in the Rubiaceae in 1789. Purportedly, de Candolle first noted this oversight, leading Meisner to describe the species as Harpagophytum procumbens DC [82]. However, de Candolle’s section of the Prodomus was only published in 1845 [83], making Meisner the author of the genus and creating the following complete citation as:

Harpagophytum DC. ex Meisner, PI. Vas. Gen. 1: 298 and 2: 206 (1840), syn.: Uncaria Burch., Trav. Int. S. Afr. 1:536 (1822), nom. illegit., non Schreb. 1789; type specimen: Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC. ex Meisner, PI. Vas. Gen. 2:206 (1840); basionym: Uncaria procumbens Burch., Trav. Int. S. Afr. 1: 536 (1822).

Decaisne, in his review of the Pedalineae, attributed four distinct species to the genus: H. procumbens DC., H. burchellii Decne. (= H. procumbens), and for the first time, H. zeyheri and H. leptocarpum [Uncaria leptocarpa (Decne.) Ihlenf. & Straka] [84]. The genus was last reviewed by Ihlenfeldt and Hartmann (1970) [1], who differentiated two species and five subspecies primarily based on the shape of the fruit correlated with the number of seeds. They also provide the most recent botanical descriptions for all subspecies.

Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC. ex Meisn.:

- H. procumbens (Burch.) DC. ex Meisn. ssp. procumbens—(1).

- H. procumbens (Burch.) DC. ex Meisn. ssp. transvaalense Ihlenf. & H. Hartm.—(2).

Harpagophytum zeyheri Decne.:

- H. zeyheri Decne. ssp. zeyheri—(3).

- H. zeyheri Decne. ssp. schijffii Ihlenf. & H. Hartm.—(4).

- H. zeyheri Decne. ssp. sublobatum (Engler) Ihlenf. & H. Hartm.—(5).

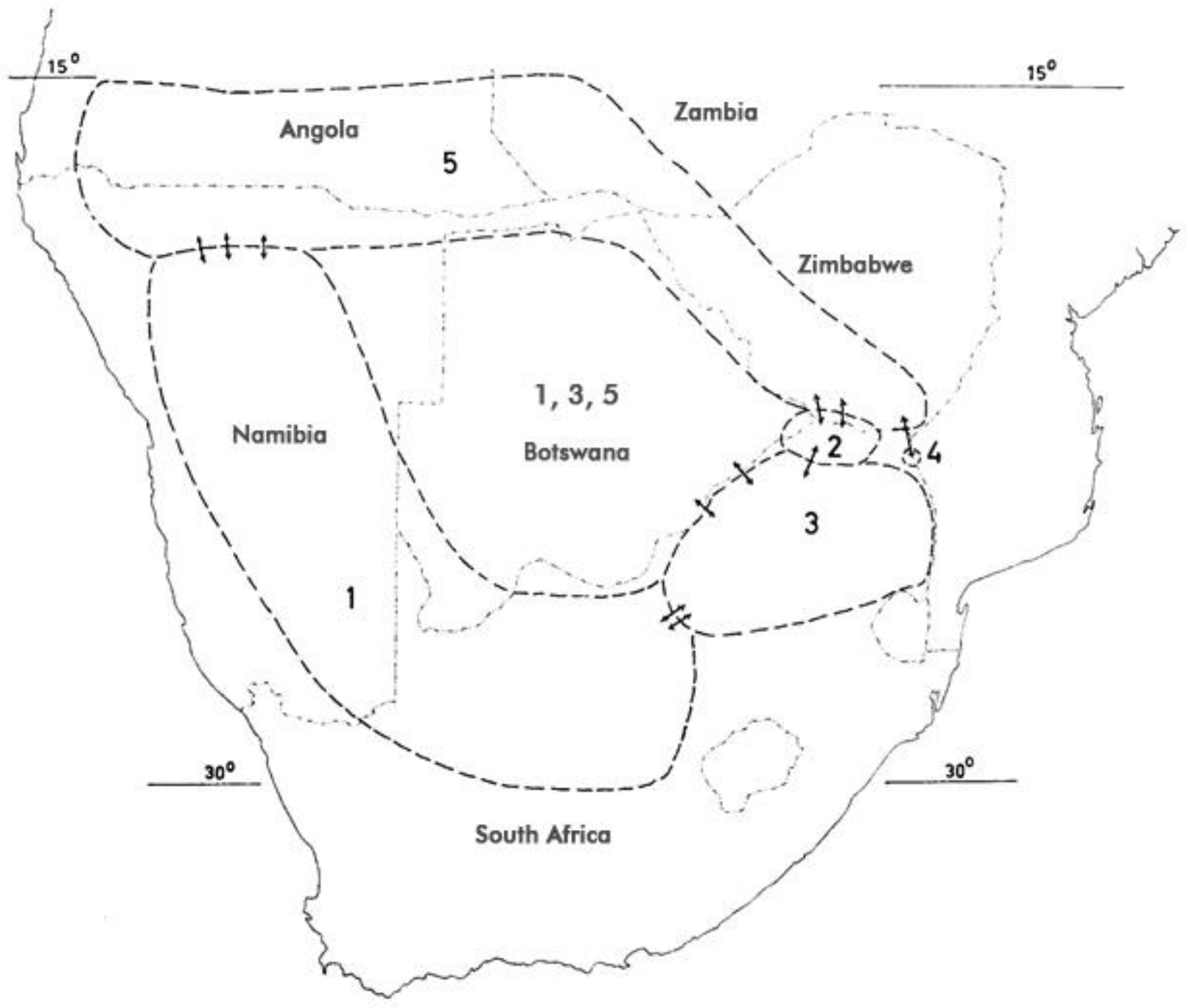

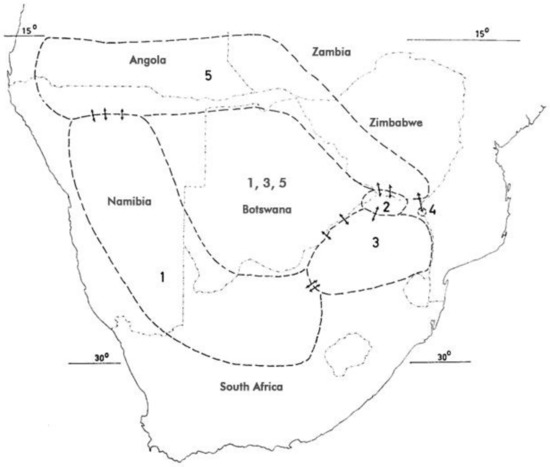

The numbers in parentheses represent the respective species in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Distribution of H. procumbens and H. zeyheri (after [1,64,91]). For numerical attribution of species, see Section 3.1. Arrows indicate introgression.

Synonymy:

- H. burchellii Decne. = H. procumbens ssp. procumbens DC. ex Meisn.

- H. zeyheri f. sublobatum Engl. = H. zeyheri ssp. sublobatum (Engl.) Ihlenf. & H. Hartm.

- H. procumbens var. sublobatum (Engl.) Stapf = H. zeyheri ssp. sublobatum (Engl.) Ihlenf. & H. Hartm.

- H. peglerae Stapf = H. zeyheri ssp. zeyheri Decne.

Interspecific introgression has been described [85] and shown to be reflected in morphometric measurements, and DNA profiles. Both species and all their putative hybrids also showed geographical variation in biochemical composition [2,85,86,87,88,89,90].

3.2. Vernacular Names

Teufelskralle, Trampelkette (Ger.); devil’s claw, grapple plant (Eng.); garra-do-diabo (Port.); garra del diablo (Esp.); artiglio del diavolo (It.); griffe du diable (Fr.); sengaparile (Tswana), duiwelsklou, kloudoring, duiwelsdoring, sanddoring, beesdubbeltjie, wolspinnekop (Afr.); otjihangatene (Oshiherero);//khuripe//khams, gamagu (Nama/Damara); elyata, omalyata (Oshikwanyama); ekatata, makakata (Oshindonga/Kwangali); likakata (Gciriku/Shambyu); !ao!ao,//xsamsa-//oro,//xemta≠’eisa (Kung); ||am-si-||q’oa-ka (West !Xoon), malamatwa (Silozi) [92,93,94].

4. Distribution

In the context of species interchangeability in commerce, it is noteworthy that the long-time assumption that only H. procumbens occurs in Namibia was disproved as early as the late 19th century. Ihlenfeldt discussed collections from the Etosha pan and later from the Kaokoveld and the Caprivi strip holding specimen of H. zeyheri [95]. Baum (1903) reported H. procumbens (Burch.) DC. var. sublobatum Engl. [= H. zeyheri Decne. ssp. sublobatum (Engler) Ihlenf. & H. Hartm.] from near lake Camelungo in southern Angola [96]. Cultivation has been experimented with in northern South Africa and, more recently, in Namibia, however, it has thus far neither proven very successful nor commercially viable [97,98,99].

5. Ethnobotany

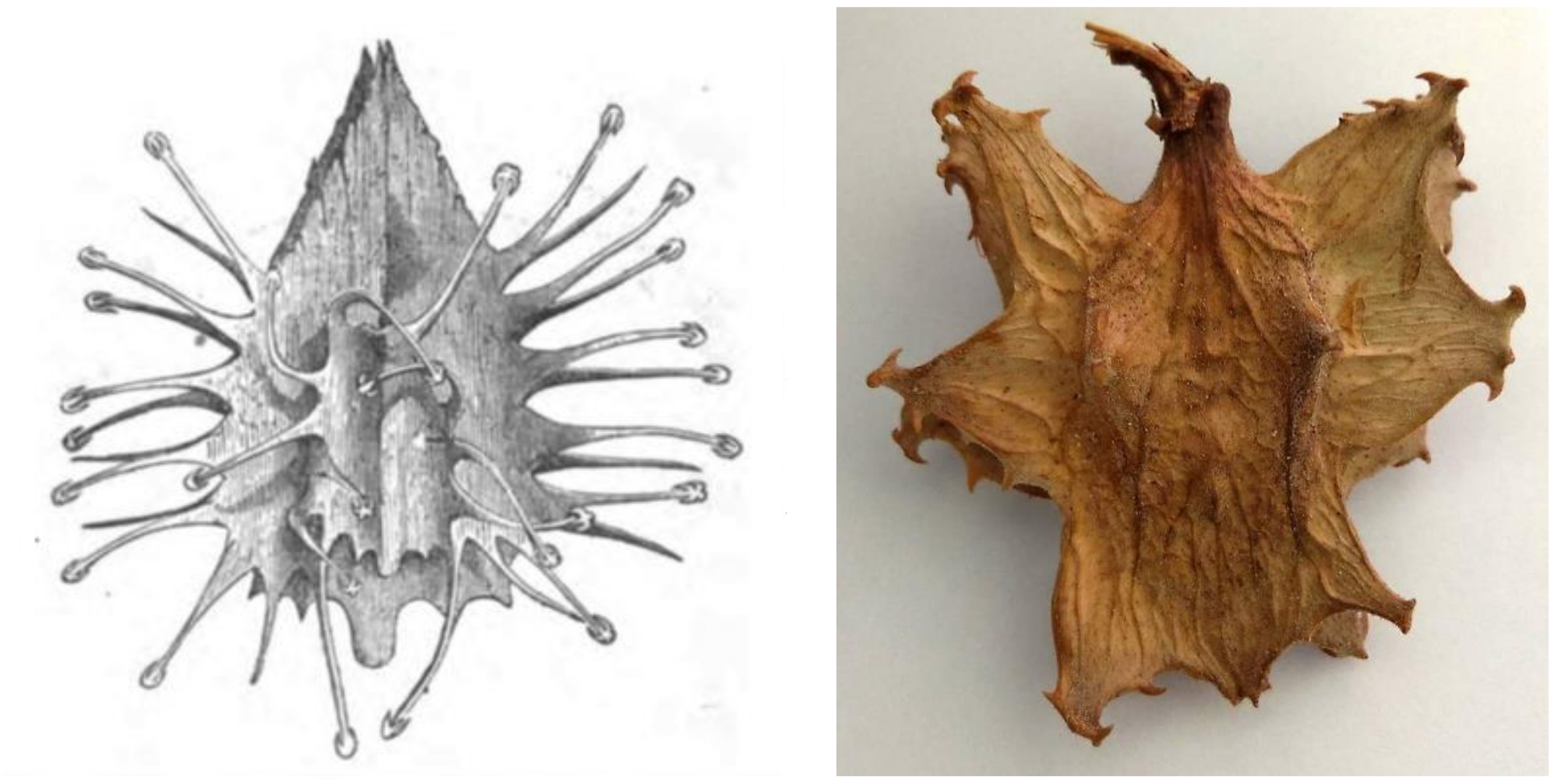

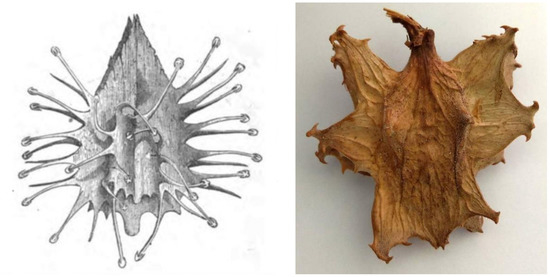

Interestingly, there are no records for indigenous use of devil’s claw until the beginning of the 20th century. Two accounts from the 19th century by Wood [100] and Cooke [101] (Figure 4) were the only ones that could be found making reference to devil’s claw (as grapple plant—Uncaria procumbens) but focus on its “devilish nature”: “The reader may easily imagine the horrors of a bush which is beset with such weapons. No one who wears clothes has a chance of escape from them. If only one hooked thorn catches but his coat-sleeve, be is a prisoner at once. […] If the reader would like to form an idea of the power of these thorns, he can do so by thrusting his arm into the middle of a thick rose-bush, and mentally multiplying the number of thorns by a hundred, and their size by fifty” [100].

Figure 4.

Fruit of the “Grapnel” (note the misspelling!) plant from [101] vs. an actual fruit (photograph by the author).

Lübbert, in 1901, provided the first unambiguous account for the use of “Kuri-Khamiknollen” (= tubers of //khuripe//khams = Harpagophytum) in wound healing [102]. In 1907, Hellwig, medical officer of the imperial protection forces in German South-West Africa (Namibia), compiled a report on medicinal plant uses of the indigenous population, including an account of the Herero Samuel Kariko of the use of “otjihangatene” (=Harpagophytum) to treat cough, diarrhea, constipation, and venereal diseases [103]. Dinter, in 1909 and 1912 [104,105], utilized this report for his account of local food plants, but unfortunately omitted to include medicinal uses because he considered them unverified [106]. The fact that Hellwig provided an explicit source renders the colorful story of how the use of devil’s claw was “discovered” by Mehnert implausible and more likely part of a marketing strategy (see below) [107].

Later accounts corroborated these early records of traditional use of devil’s claw tubers primarily in the form of infusions and decoctions for digestive purposes, midwifery, pain relief, fever, diabetes, as a general tonic, for infectious diseases, and the dry powder topically as a wound dressing [40,92,108,109,110,111,112]. Ethnoveterinary uses in poultry have also been reported from Botswana [113]. It must be noted, however, that none of the early records clearly differentiate between species. It can only be speculated based on the origin of the records that Nama/Herero may have referred to H. procumbens, whereas reports from Botswana would concern mostly H. zeyheri.

6. Economy

6.1. History of Commercialization

The story around how a soldier of the Kaiserliche Schutztruppe (German “imperial protection forces”) and later a farmer in Mariental (Namibia) Gottreich Hubertus Mehnert came across devil’s claw is firmly anchored in the scientific literature. Sometime during the so-called Hottentot uprising from 1904 to 1908 (in fact, a brutal war and genocide of the German troops primarily against the Herero and Nama tribes, which has most recently been recognized by the German government [114]), after observing a local healer successfully improving the condition of a gravely wounded local, he questioned the healer about the magic remedy, but the healer refused to disclose the place from where he had collected it. Purportedly, access to one of the most successful botanical drugs of modern times can be attributed to Mehnert’s pointer dog [107].

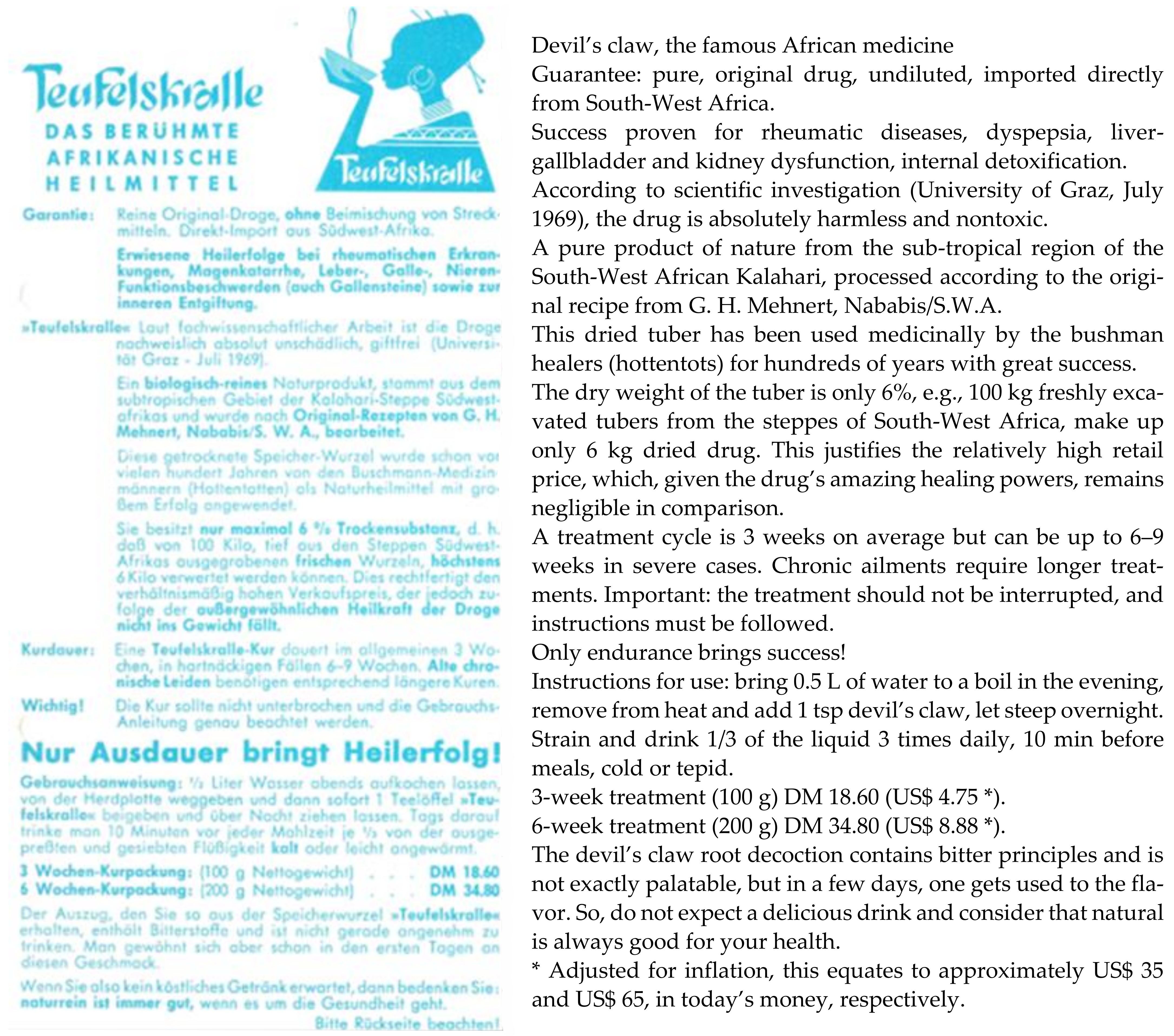

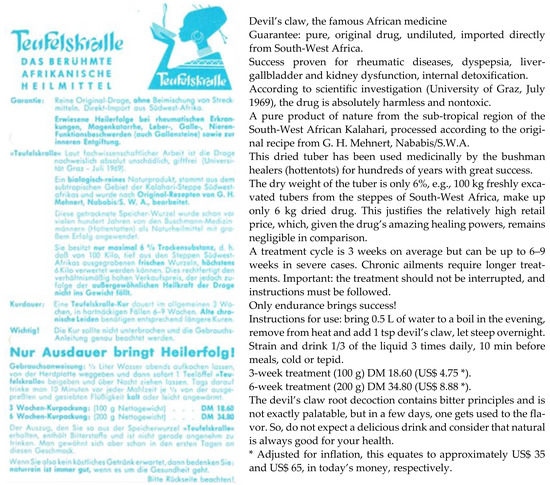

This version, however, must be relegated to the world of “romance” and seen as part of an elaborate marketing campaign—it is repeated in many slightly altered versions by multiple authors. Mehnert doubtlessly experimented with the root and found it effective in a variety of ailments, but the discovery of its medicinal powers ought to be attributed first and foremost to the native tribes and secondarily to Lübbert and Hellwig (see above) with whom they shared their knowledge. It was sheer luck that nobody else developed an interest, allowing Mehnert to consolidate his “research” and to commence commercialization. He eventually shared it, while being interned at camp Andalusia during the 2nd World War, with another “collateral” prisoner, German scientist O. H. Volk, who had visited German South-West Africa at the wrong time [115]. In the camp’s botanical society, knowledge was freely exchanged, which allowed Volk to return home to Germany with likely an entire laundry list of interesting plants. The introduction of devil’s claw (and probably also rooibos) to Germany can be attributed to him [58]. He shared his knowledge with Zorn who conducted some initial pharmacological research [116] and then initiated himself a flurry of investigations elucidating devil’s claw’s basic chemistry [117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128]. Meanwhile, in the early 1950s, Mehnert trademarked “Harpago” and started exporting to Germany. Erwin Hagen trademarked “Harpago” in Germany in the early 1960s and began to market it as an infusion and later in homoeopathic preparations [129] (Figure 5). “Harpagosan” tea was registered as a botanical drug in Germany in 1977 [130].

Figure 5.

Advertisement Fa. Hagen (early 1970s).

What follows is a story of extensive biochemical, pharmacological, toxicological, and clinical investigation, and the development of multiple standardized pharmaceuticals, initially in Germany (the German drug information system AMIce alone lists a total of 434 products, most of which, however, are no longer active, see, e.g., [131]), and since the 1980s, also in France and elsewhere [132]. Demand quickly started to grow exponentially, and concerns were raised over the sustainability of harvesting practices [133,134,135]. In response to unsustainable harvesting and poor processing practices, the Namibian Devil’s Claw Exporter’s Association Trust became part of a Good Agricultural and Collection Practice (GACP) project in which it intends to ensure that Namibian devil’s claw is sustainably harvested and processed according to GACP guidelines.

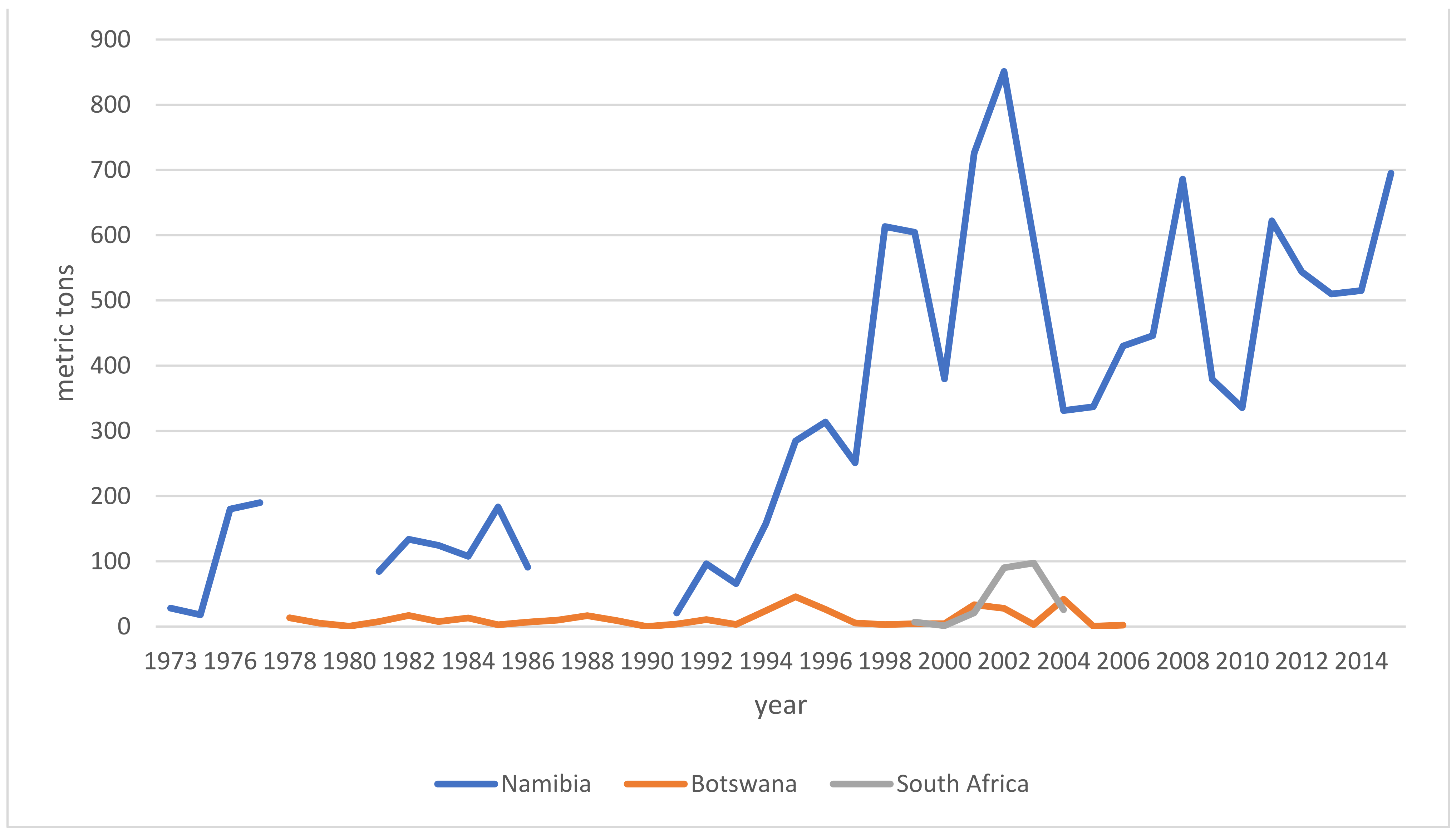

6.2. Trade

Market demands impact livelihoods and policymakers alike. Trends indicate the health of an industry and inform resource assessments as well as regulatory interventions. With the following breakdown of trade and export data, I intend to address a controversy around species interchangeability, namely how the ingredient is regulated in the finished product markets. Hagen and others created a demand which local suppliers struggled to meet [133,134,135]. Sustainable collection and harvesting practices and governmental oversight were largely absent until ~1975. When originally only H. procumbens had been collected, driven by the economic boom, the collection and admixture of H. zeyheri commenced as early as the 1970s [11,12,13,14]. Furthermore, albeit on a much smaller scale than Namibia, both South Africa and Botswana [136,137,138] began to participate in the export market, also adding H. zeyheri into the supply chain (for distribution see above). Nott [14] and Taylor and Moss [138] broke down data specific to importing countries and explicitly listed importers, respectively. It is therefore safe to state that all importing markets have received either both species or mixtures thereof as early as the late 1970s. European regulators acknowledged the commercial reality by adding H. zeyheri to pharmacopeial monographs (see Section 6), while the US, for instance, remained oblivious to this practice, which stirred a controversy over the regulatory compliance and legitimacy of products containing H. zeyheri in 2015 [139]. The following overview of export volumes (Figure 6) is compiled from multiple sources [10,14,18,136,137,138,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151] and further informed by the Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET). The MET stopped sharing its data—based on export permits—with the public in 2015. According to one of the most prominent Namibian exporters of devil’s claw, the years 2015–2020 saw a slight increase in demand, peaking in 2019 at around 1000 metric tons, otherwise averaging around 700 metric tons annually. Materials in trade (both species) fall into four categories: conventional (lowest) quality makes up about 80% of the trade volume, GACP quality currently contributes about 10–15% to the total, though efforts are underway to dramatically increase this proportion, certified organic quality adds organic certification to GACP-compliant material and makes up about 5–10% of the total trade volume, and finally, organic and Fair for Life certified material (H. procumbens only) contributes ~1% to the trade total. Prices per kg (for full container loads, cost and freight) range from €4.00 (H. zeyheri) and €6.70 (H. procumbens) for conventional quality, via €5.40 (H. zeyheri) and €8.20 (H. procumbens) for GACP quality, and €7.20 (H. zeyheri) and €8.50 (H. procumbens) for organic quality, to €9.00 for Fair for Life certified material (pers. comm. G. Diekmann, EcoSo Dynamics cc, Namibia). While these prices and volumes make this a sizeable industry, it must be noted that most of the value is of course added during the manufacture of pharmaceuticals in the target markets. It is also noteworthy that over all this time, Namibian exports may have been bolstered by (illegal) imports from Angola and Zambia, for which—naturally—no records exist [152].

Figure 6.

Devil’s claw exports by country—gaps reflect years in which no data was reported.

7. Representation in Pharmacopeias and Authoritative Compendia

Given its presence in the European marketplace since the 1950s and in the US at least since the late 1970s, pharmacopeial standards for devil’s claw were set surprisingly late, likely due to suitable analytical methods not being available. While a qualitative assessment for the bitterness value according to the German Pharmacopoeia 7 (DAB 7) was suggested as early as 1977 [11], no specific monograph for devil’s claw was included in DAB until 1993, which, in fact, required testing for harpagoside content (see Table 1 below). The first monograph in Europe appeared in the British Herbal Pharmacopoeia in 1981. Devil’s claw first appeared in the European Pharmacopoeia in 1995, H. zeyheri, however, was not included as an allowable source species until 2003. The US Pharmacopeia, on the other hand, does not have a monograph for devil’s claw other than a draft proposal published in the Herbal Medicines Compendium in 2013 [153].

Table 1.

Representation of devil’s claw in pharmacopeias and authoritative compendia.

8. Biochemistry

After Volk’s return to Germany (see Section 6.1) and following Zorn’s first pharmacological study of devil’s claw in 1958 [116], the university of Würzburg (Germany) became a research hotspot for the elucidation of active and suitable marker compounds in devil’s claw for decades to come. The effort was largely concluded by the end of the 1980s and comparatively little has been added to this effort since. Table 2 lists all publications focused on the biochemical composition. For analytical methods and quality control, see Section 9.

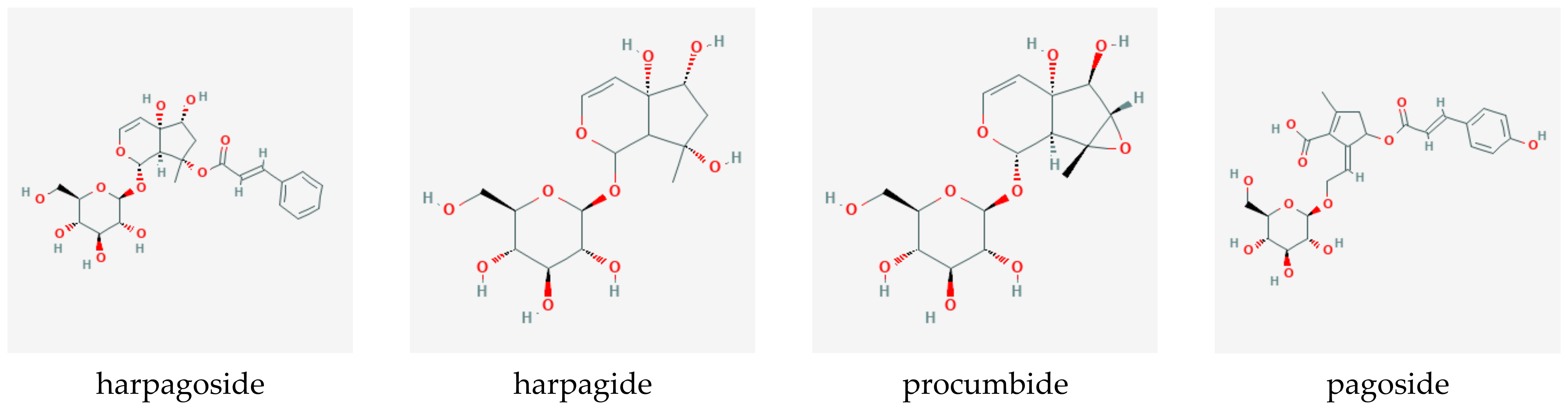

Iridoid-glycosides, primarily harpagoside, harpagide, and procumbide; phytosterols; phenylpropanoids such as verbascoside; triterpenes, such as oleanolic acid, 3β-acetyloleanolic acid, and ursolic acid; flavonoids, such as kaempferol and luteolin; unsaturated fatty acids, cinnamomic acid, chlorogenic acid, and stachyose were identified as the most prominent compounds present in the root. Figure 7 shows the chemical structures of the primary iridoid glucosides present in Harpagophytum root.

Figure 7.

Iridoid glucosides present in devil’s claw root (source PubChem).

Interestingly, the biosynthetic pathway for harpagoside is not yet well-elucidated. The first step resulting in geranyl diphosphate is still considered to be under debate [17], since while the principal steps are known, some intermediates remain hypothetical and dependent on the “chosen” pathway. Georgiev and colleagues [30] propose two different routes to the formation of geranyl diphosphate from the condensation of dimethylallyl diphosphate and isopentenyl diphosphate, the latter being supplied through either the mevalonate or the mevalonate-independent pathways. Geraniol is synthesized by geraniol diphosphate synthase and hydroxylated to form 8-hydroxygeraniol, followed by two oxidation steps and isomerization into 8-epi-iridodial. Carboxylation and glycosylation form its glycoside, which, in turn, is transformed into harpagide through decarboxylation and oxidations. Finally, harpagoside emerges as the product of cinnamoyl esterification at the 3-hydroxyl position.

Several studies have investigated differences in the quantitative composition of different Harpagophytum species, subspecies, and hybrids [19,181,182,183,184], and found the composition to be highly variable, depending on the material used, collection location, natural variation within the taxa, environmental influences, processing, and analytical methods. Content of the marker compound harpagoside is generally lower in H. zeyheri and has been found to be between 0%, 1%, and 4% in H. procumbens and between 0% and 3% in H. zeyheri. Verbascoside and isoverbascoside contents in H. procumbens varied between 0.2% and 0.4% and 0.2% and 1%, respectively. Pagoside content in H. procumbens varied between 0.06% and 0.16%. Hybrids showed the highest contents for most key compounds except harpagoside. 8-p-Coumaroylharpagide content in H. zeyheri varies between 0.7% and 1.4%, while being effectively absent in H. procumbens. The lower harpagoside content in H. zeyheri has in the past driven controversies over species equivalence in terms of clinical efficacy, however, this debate seems futile as a marker compound is not necessarily the (only) active one. Indeed, the pre-clinical research (outlined in Section 10) indicates that activities of multiple rather than single compounds may contribute to the overall effect.

Table 2.

Elucidation of the biochemical composition of devil’s claw root.

Table 2.

Elucidation of the biochemical composition of devil’s claw root.

| Topic | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Isolation and characterization of harpagoside | 1960 | [117] |

| Stachyose, raffinose, and a further glucoside in the aqueous phase | 1961 | [118] |

| Characterization of harpagoside | 1961 | [119] |

| Isolation and characterization of harpagoside and harpagide | 1962 | [120] |

| Characterization of harpagoside | 1962 | [121] |

| Characterization of harpagide | 1963 | [122] |

| Isolation of stachyose and a further glucoside | 1963 | [123] |

| Characterization of harpagoside | 1964 | [124] |

| Isolation of procumbide | 1964 | [125] |

| Structural characterization of harpagoside | 1966 | [126] |

| Characterization of procumbide and further constituents | 1967 | [127] |

| Characterization of procumbide | 1968 | [128] |

| Characterization of a chinone and other constituents | 1970 | [185] |

| Characterization of procumbide | 1971 | [186] |

| Further constituents | 1974 | [187] |

| Elucidation of triterpene esters | 1975 | [188] |

| Overview of known mono-, di-, and sesquiterpenoids with pharmacological activity | 1977 | [189] |

| Elucidation of a resin, an essential oil, and a mucilaginous fraction | 1978 | [190] |

| Structural characterization of procumbide | 1979 | [191] |

| Glucose, galactose, fructose, myo-inositol, sucrose, raffinose, and stachyose identified | 1979 | [192] |

| Preparation and structure of harpagogenine | 1981 | [193] |

| Carbohydrates and harpagoside in tissue cultures and roots of devil’s claw | 1982 | [194] |

| New iridoids: 8-O-(p-coumaryl)-harpagide and procumboside | 1983 | [195] |

| Novel iridoid and phenolic compounds | 1987 | [196] |

| Three pyridine monoterpene alkaloids from harpagoside and commercial extract | 1999 | [197] |

| Review of iridoids | 2000 | [198] |

| Review of composition (both species) | 2002 | [199] |

| Two diterpenes, (+)-8,11,13-totaratriene-12,13-diol and ferruginol | 2002 | [200] |

| New iridoid- and phenylethanoid glycosides | 2003 | [201] |

| Acetylated phenolic glycosides | 2003 | [202] |

| Pharmacological characterization of harpagoside | 2004 | [203] |

| Chinane-type tricyclic diterpenes and other minor compounds | 2006 | [204,205] |

| Review of iridoids and other compounds | 2006 | [206,207] |

| Review of chemical constituents | 2007 | [208] |

| Elucidation and characterization of compounds with specific pharmacologic profiles | 2008 | [209,210] |

| New triterpenoid glycoside, harproside, and new iridoid glycoside, pagide | 2010 | [211] |

| Kynurenic acid content | 2013 | [212] |

| New iridoid diglucoside | 2016 | [213] |

9. Analytical Methods and Quality Control

The quickly increasing popularity of devil’s claw products required an ongoing effort to develop and refine tools to identify and quantify devil’s claw in its raw, processed, and finished product states. Initially, the primary aims were identification and contaminants [214,215], later, standardization [11] and quality control [216,217], and finally identification and quantification methods to support pharmacological and clinical research. Early methods, however, did not account for species differentiation, i.e., simple pharmacy-proof methods of the 1970s would likely not have been able to differentiate between H. procumbens and H. zeyheri. In fact, methods and equipment refined enough to do so, regardless of the extent of processing, only became available in the 1990s. Analysis of retention samples retrospectively determined the presence of both species in commercial products. Table 3 provides a quick reference to publications of methods of quality control in chronological order. In current practice, the most commonly used methods for identification and assaying devil’s claw raw materials and products include TLC, HPLC, HTPLC, and LC/MS, for instance, the current edition of the European Pharmacopoeia employs microscopy and TLC for identification and LC for harpagoside quantification; more recently, chemometric modeling and hyperspectral imaging have emerged as promising methods for species differentiation.

Table 3.

Analytical methods and methods of quality control.

10. Processing, Products, Applications

The majority of data on processing and delivery systems is provided in the list of patents compiled in Section 14. EMA’s HMPC assessment report on H. procumbens and/or H. zeyheri, radix, provides an overview of extracts that are most commonly used in commercial products [167]:

- Liquid extract (1:1; 30% v/v ethanol)

- Soft extract (2.5–4.0:1; 70% v/v ethanol)

- Dry extract (1.5–2.5:1; water)

- Dry extract (5–10:1; water)

- Dry extract (2.6–4:1; 30% v/v ethanol)

- Dry extract (1.5–2.1:1; 40% v/v ethanol)

- Dry extract (3–5:1; 60% v/v ethanol)

- Dry extract (3–6:1; 80% v/v ethanol)

- Dry extract (6–12:1; 90% v/v ethanol)

- Tincture (1:5), extraction solvent ethanol 25% (v/v)

Figure 8 shows the processing from harvest to the raw material in commerce. Historically, teas [67,274], e.g., Harpagosan (see above), fluidextracts [42,67], spray-dried aqueous extract [26,67], homeopathic preparations for both oral (p.o.) and intraperitoneal (i.p.) application [26,27,67], and powder in capsules [26,67,93] were also common galenic forms. The European Pharmacopoeia stipulates a minimum of 1.2% of harpagoside in the raw material [169]. Dry extracts were standardized to contain a minimum of 1.5% m/m of harpagoside [167].

Figure 8.

Clockwise: H. procumbens, secondary tubers, drying of the sliced tubers, article of commerce (photographs by the author). The article of commerce shown here is conventional quality (see Section 6). Note the difference in color of the slices shown on the bottom right, which were harvested and processed in compliance with GACP.

More recently, Plaizier-Vercammen and Bruwier evaluated the impact of excipients on friability and hygroscopicity of direct compression of a spray-dried Harpagophytum extract [275]. Günther et al. analyzed the parameters affecting supercritical fluid extraction with CO2 of harpagoside [276]. Performance of a topical preparation with devil’s claw extract on acrylic acid polymers base compared to ketoprofen was assessed by Piechota-Urbanska and colleagues [277]. Both formulations demonstrated rheological stability and high pharmaceutical availability. Almajdoub described a freeze-dried aqueous extract of H. procumbens encapsulated in lipid vesicles by using a dry film hydration technique with and without further alginate coating for optimal (delayed) release and small intestine absorption [278]. Development of a gastro-resistant coated tablet prepared from a standardized hydroethanolic root extract for the purpose of more effective delivery and consequent dose reduction was reported by Lopes et al. [279].

11. Pre-Clinical Research

11.1. Pharmacology

Studies mainly investigated anti-inflammatory activities and were conducted with various extracts, extract fractions, or isolated compounds. Harpagophytum iridoid compounds are considered the primary actives, to which anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, analgesic, antimicrobial, chemopreventive, hepatoprotective, neuroprotective, and immunomodulatory effects are commonly attributed [189,198,209,280,281]. As cyclooxygenase (COX)-1/2 inhibitors have emerged as important targets for treating rheumatoid arthritis, the influence on the arachidonic acid pathway has been a research focus. The most commonly used methods for measuring peripheral analgesic activity were the various forms of the writhing tests, hot-plate test, and the Randall–Selitto test in rats and mice. To demonstrate anti-inflammatory effects, different animal models of inflammation were commonly used, e.g., the carrageenan-induced mouse/rat paw edema, the 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced mouse edema, the granuloma pouch test, zymosan-induced arthritis, albumin-induced rat paw edema, adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats (M. tuberculosis; Freund adjuvant), and Adriamycin-induced rat paw edema. More advanced in vivo and a variety of in vitro and ex vivo models were developed and employed over time (see Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 below).

Table 4.

In Vitro experiments regarding analgesic/antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of devil’s claw preparations and compounds.

Table 5.

In Vivo experiments regarding analgesic/antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of devil’s claw preparations and compounds.

Table 6.

Ex vivo experiments regarding analgesic/antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of devil’s claw preparations and compounds.

Table 7.

Mixed experiments regarding analgesic/antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of devil’s claw preparations and compounds.

Investigated targets for anti-inflammatory effects and their respective IC50 (significant inhibitions, primary sources only) are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Anti-inflammatory targets of Harpagophytum preparations and compounds.

Table 9 summarizes the results of pre-clinical experiments which studied other effects of Harpagophytum and its compounds.

Table 9.

Experiments regarding other effects of devil’s claw preparations and compounds.

Primary—anti-inflammatory, analgesic/antinociceptive, and antioxidant—effects have been demonstrated in multiple in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo assays with crude extracts, fractions, and isolated compounds of Harpagophytum. However, experiments show some inconsistencies, likely caused by deviations in experimental models and insufficient characterization of the purportedly active compounds, as well as variation in solvent systems [394,395,396]. Further, the consolidated data show that efficacy cannot be clearly attributed to any one of the compounds present in Harpagophytum. Focus on harpagoside—albeit serving as a convenient marker—cannot be substantiated in an efficacy context. On the other hand, the presence and effect of verbascoside in Harpagophytum, a compound with well-documented anti-inflammatory properties, has not been adequately studied.

11.2. Pharmacokinetics

Most of the available pharmacokinetics data were created as a byproduct or in the context of pharmacological experiments with Harpagophytum preparations or its compounds. Vanhaelen [52] experimented with harpagoside and harpagide under conditions mimicking those found in the stomach and concluded by suggesting enteric-coated preparations for harpagoside to slow down acid hydrolysis. Chrubasik [217] investigated release and stability of harpagoside in gastric and intestinal fluids and stability for 3 and 6 h, respectively. The author also found harpagoside to be of low bioavailability, a daily dose of 100 mg could not be detected in serum or urine. Chrubasik et al. (2000) [238] established an octanol–water distribution coefficient of approximately 4 that is not dependent on pH or temperature.

Neither Harpagophytum ethanolic extract nor harpagoside had a relevant effect on cytochrome P (CYP) 450 3A4 in vitro [397]. An investigation of different Harpagophytum extracts elucidated maximum levels of plasma harpagoside after 1.3 to 2.5 h and suggested a correlation between serum harpagoside levels and inhibition of leukotriene biosynthesis in vitro and ex vivo [285,398]. In human liver microsomes and subtype-specific CYP substrates, Harpagophytum at a dose derived from [157] activated CYP 2E1 and inhibited CYP 2C19 [399]. Inhibition of CYP 450 was shown for methanolic extracts of H. procumbens, and while inhibition of CYP 1A2 and 2D6 was relatively low, moderate inhibition of CYP 2C8/9/19 and 3A4 was noted (IC50 between 100 and 350 μg/mL) [400]. However, the impact on drugs metabolized via those enzymes is merely theoretical. Romiti et al. [401] found Harpagophytum to interact with the multidrug transporter ABCB1/P-glycoprotein, unrelated to relative harpagoside content. Modarai et al. [402] found Harpagophytum preparations, but not harpagoside or harpagide, to weakly inhibit CYP 3A4, but deemed clinical relevance unlikely.

11.3. Toxicology

Acute and chronic toxicity have been investigated for the herbal substance, its preparations, and compounds isolated from Harpagophytum. Multiple publications cite an unpublished experiment by Albus (1958) in which an LD50 in mice was established for a liquid extract (not specified) at 34 mL/kg i.v. and 220 mL/kg p.o. [22,42,51,120]. An LD50 in rats was given at 10 g/kg for a spray extract and in mice at 1 g/kg for harpagoside [403]. Vollmann [379] established an LD50 of 23 and 10 mL/kg for an infusion and a chloroform/butanolic extract (4:1), respectively. Möse [404], in an unpublished report (cited in [27,44,67,405]) conducted toxicity tests with a Harpagophytum infusion in primate and chicken tissue cultures, and no effect on cell development was found, nor did the infusion promote growth of Ehrlich ascites carcinoma in mice. Eichler and Koch referenced toxicity at above 0.5 g/kg without citation [305]. Erdös and colleagues [308] demonstrated Harpagophytum aqueous, methanolic, and butanolic extracts to be effectively non-toxic (LD0 at 4640 mg/kg p.o. and >1000 mg/kg i.v.), and for harpagoside, a LD0 of 395 mg/kg and a LD50 of 511 mg/kg. Marzin (1978, cited in [67]) confirmed these results. The same author investigated the toxicity of an extract (2.7% total iridoids), p.o. or i.p., in rats and mice. Administration p.o. was effectively non-toxic, while i.p., some toxicity was observed with a calculated LD50 of 10 g/kg (Marzin, 1981, cited in [274]). Vanhalen and colleagues tested toxicity of harpagoside and harpagide in mice and established an LD50 of 1 and 3.2 g/kg, respectively [224]. Schmidt [44] elaborated unpublished toxicological investigations with Harpagophytum D2 and Harpagosan (DER 2:1) [406,407], establishing an LD50 of 20 mL/kg and >30 mg/kg, respectively. Whitehouse et al. [341] established an LD50 at 13.5 g/kg p.o. for a Harpagophytum root extract (not specified) in mice and no toxicity at 7.5 g/kg over three weeks in rats, while 2 g/kg over one week showed no impact on liver parameters. Ibrahim et al. [408] conducted a battery of toxicity studies in mice (acute, sub-acute, and chronic) with a commercial product (Boiron, France—composition not declared) and found no clinically relevant changes in any of the tested outcomes, attributing a slight increase in liver enzymes to the anti-inflammatory effect. Al-Harbi and colleagues [409] found no oral acute toxicity in mice at 1 and 3 g/kg Harpagophytum powder. In a 90-day chronic toxicity study (test substance not characterized), no clinically relevant changes in tested parameters were established, except for a significant decrease in blood sugar and uric acid levels. Both chronic assessments, however, must be considered inadequate due to the insufficiently characterized test material. Allard et al. [410] discussed herb-induced nephrotoxicity, and in that context, called for further investigation of whether a theoretical impact of Harpagophytum on major renal transport processes is of clinical relevance. Joshi et al. [411] investigated the toxicology of a H. procumbens aqueous-ethanolic extract (1 g/kg/day, equivalent to 7.5–10× the human recommended dose) in male and female Sprague Dawley rats over 4 and 12 weeks. While no significant histopathological effects were found, the study yielded significant—albeit not clinically relevant—sex-related differences in blood chemistry. All these results stand in stark contrast to those of Zorn [116], casting considerable doubt over the authenticity of the plant material used in his experiments.

Mahomed and Ojewole [412,413] conducted experiments in vitro suggesting spasmogenic and uterotonic actions for an H. procumbens aqueous extract (10–1000 µg/mL). Whether these results are of clinical relevance in vivo remains to be established (see Section 11.2). Pearson [414] studied the reproductive toxicity of a combination product containing Harpagophytum (exact composition not disclosed) for veterinary use in pregnant female Sprague Dawley rats and showed no signs of toxicity. The study, however, is poorly reported and of limited relevance given the unknown composition of the test substance. Contrarily, Davari and colleagues [415] reported teratogenic effects and histopathological changes in fetal tissues (but no significant structural malformations or abnormalities) from an experiment with H. procumbens (200, 400, 600 mg/kg) in pregnant Balb/C mice.

12. Clinical Research

12.1. Efficacy

The efficacy of devil’s claw has been investigated in more than 50 human studies, and case reports and observational studies are summarized in Table 10, while randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) are summarized in Table 11. Indications were primarily degenerative joint diseases as well as low back pain. Trials utilized a variety of methodological designs, with different preparations of devil’s claw and daily doses of harpagoside, varying from <30 to >100 mg. While harpagoside is considered to contribute to the overall activity of devil’s claw preparations, it is not yet fully understood which other compounds may also be of relevance. Furthermore, an investigation into the harpagoside content of commercially available devil’s claw preparations revealed substantial variation, with contents often below the recommended daily dose of 4.5–9 g crude drug (equivalent >50 mg harpagoside) [173,232,233,234,237,416].

Trials have been reviewed systematically with regards to their quality and results concerning safety and efficacy of Harpagophytum preparations in publications between 1973 and 2019 [17,23,139,156,417,418,419,420,421,422,423,424,425,426,427,428,429,430,431,432,433]. Another set of reviews considered the efficacy of devil’s claw preparations or its active compounds in specific need states [23,130,434,435,436,437,438,439,440,441,442,443,444,445,446,447,448,449,450,451,452,453,454,455,456,457,458,459,460,461,462,463,464,465,466,467,468,469,470,471,472,473,474,475,476,477,478,479,480,481,482,483,484,485,486,487,488]. All trials observed improvement of the outcome criteria under treatment (some significant), however, significant superiority of the Harpagophytum preparations vs. conventional NSAIDs was not reported. This is partly because most trials were observational and/or comparative, while the outcomes of placebo-controlled trials were often inconclusive or overshadowed by methodological deficiencies. Many trials allowed for conventional emergency or co-medication, which further limits the value of the data collected. Despite some studies providing evidence for the effectiveness of certain preparations, the overall quality of evidence is not sufficient. Furthermore, the relevance of early studies with homeopathic dilutions—while included here for completeness’ sake—is limited from a perspective of rational phytotherapy.

Table 10.

Case reports and observational studies conducted between 1971 and 2021.

Table 10.

Case reports and observational studies conducted between 1971 and 2021.

| Indication | Trial Type, Size | Results | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemosis | CR 1 | Initial treatment with multiple preparations that did not lead to improvement, then with 300 mg Harpagophytum extract (not specified) 3 times daily, orally, for 6 months, leading to drastic improvement. | 1983 | Belaiche [489] |

| Familial Mediterranean fever | CR 17 | Harpagophytum extracts characterized as aqueous (DER 1:2.4, 2.5% harpagoside)—this characterization may also apply to previous trials by Belaiche and Dahout (see above)—6–9 g single dose, duration not provided; significantly decreased recurrence in 80% of patients. | 1983 | Belaiche [490] |

| Cancer | CR 2 | Tumor regression after taking Harpagophytum extract (500 mg daily) and/or Essiac respectively, without cytotoxic therapy. | 2009 | Wilson [491] |

| DJD | O ~120 | Harpagophytum D4–D6, IA, and D1 orally; 1–6 months; substantial improvement of symptoms in most cases. | 1971 | Beham [492] |

| CP | O 60 | Harpagophytum D2, IA, plus tea (2–3 tsp per 1 L water) or 3 × 2 tablets orally, duration not provided; dose-dependent response; 60% substantial improvement of symptoms, 20% improvement, 20% no change. | 1972 | Schmidt [43] |

| CP, DJD | O 146 | Harpagophytum D2, IA, duration not provided; improvement in 134 patients. | 1972 | Zimmermann, cited in [130] |

| DJD | O 25 | Harpagophytum D2–D3, IA, and SC, 1–2 mL, pain-free after 6 injections, or tea (1 tsp per 300 mL) daily for 3–6 weeks. | 1972 | Brantner [493] |

| DJD | O 70 | Harpagophytum D2, IA, some + tea, some + indometacin, duration not provided; improvement in 90% of patients. | 1976 | Wilhelmer, cited in [44] |

| CP, DJD | O 21+ | Harpagophytum D1–D3, IA, SC, and i.v., tea, orally, duration not provided; significant improvement in 30% of patients. | 1977 | Zimmermann [494] |

| DJD | O 84 | 250 or 500 mg Harpagophytum extract (not specified) 3 times daily orally for 2–6 months, improvement in 72% of patients. | 1979 | Dahout, cited in [495] |

| CP, DJD | O 600 | Harpagosan tea (2 tea bags in 500 mL water daily) plus D2 SC for up to 6 months. Symptoms disappeared in 200 patients; 400 patients improved after having received additional conventional medication for the first 3–4 weeks. | 1983 | Warning cited in Schmidt [44] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | O 1 | Improvement after treatment with low-potency Harpagophytum i.v. and orally, duration not provided. | 1987 | Stübler [496,497] |

| DJD | O 553 | Patients treated with 2–6 capsules of 400 mg Harpagophytum extract (1.5–2.5:1) for 8 to 180 days. Outcomes confirmed RCT results in terms of efficacy and safety. | 2000 | Müller et al. [498] |

| DJD | O 255 | Post-marketing surveillance study of biopsychosocial determinants and treatment response. Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (60 mg harpagoside/day) for 2 months. Outcome parameters were significantly worse in non-responders. | 2009 | Thanner et al. [499] |

| CP, DJD, dyspepsia, hypercholesterolemia, detoxication | O, CR 700+ | Harpagophytum tea, up to 12 weeks, D2, SC, 20 injections, further improvement with additional D2 i.v. and tea. | 1978 | Schmidt [130] |

| Diabetes mellitus with lipometabolic disorder | OT 10 | 4 patients 3 weeks, 6 patients 4 and 3 weeks, over a total of 6 months; Harpagophytum tea, amount not specified; cholesterol, lipid, and blood sugar levels normalized. | 1974 | Hoppe [500] |

| Hypercholesterolemia and hyperuricemia | OT 100 | Harpagophytum tea, 2 tea bags per ½ L water, 3× daily before meals 1/3 of the tea; 20–21 days; lowered cholesterol levels in 80%, normal levels in 45%, 66% improvement in hyperuricemia. | 1978 | Grünewald [405] |

| DJD | OT 13 | Harpagophytum extract (<30 mg harpagoside/day), for 6 weeks, followed up for another six weeks; no overall statistically significant improvements in the conditions. | 1981 | Grahame and Robinson [501] |

| DJD | OT 630 | 42% to 85% of the patients (depending on grouping) showed improvements after 6 months with Harpagophytum extract (>90 mg harpagoside/day). | 1982 | Belaiche [502] |

| DJD | OT 38 | Comparison of Formica rufa D6 with Harpagophytum D4, for 3 months; improvement in pain severity and mobility with both, Formica rufa slightly superior. | 1991 | Kröner [503] |

| Effect on eicosanoid biosynthesis | OT 34 (25/8) healthy volunteers | Harpagophytum, 4 capsules (500 mg powder, 3% of total glucoiridoids) daily for 21 days. No effect vs. control. | 1992 | Moussard et al. [504] |

| MSD | OT 102 (51,51) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (30 mg harpagoside/day) or conventional therapy (mainly oral NSAIDs). Number of pain-free patients and changes in Arhus scores after 4 and 6 weeks of treatment was comparable between the groups. | 1997 | Chrubasik et al. [505] |

| DJD | OT 43 | Harpagophytum powder 3 g daily for 60 days. Reduction of pain intensity in 89%, increased mobility in 83%. | 1997 | Pinget and Lecomte [506] |

| MSD | OT 2053 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (30 mg harpagoside/day) for 6 weeks. Symptoms improved over time. | 1999 | Schwarz et al. [507] |

| DJD | OT 45 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (30 mg harpagoside/day) for two weeks plus NSAID treatment, and devil’s claw alone, for four weeks. No worsening of scores was observed during treatment with devil’s claw alone. | 2000 | Szczepanski et al. [508] |

| MSD | OT 1026 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (30 mg harpagoside/day) for 6 weeks. Symptoms improved. | 2000 | Usbeck [509,510] |

| MSD | OT 130 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (~30 mg harpagoside/day) for 8 weeks. Arhus back pain index decreased significantly during treatment. Other measures also improved significantly. | 2001 | Laudahn et al. [511,512,513] |

| DJD | OT 583 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (~30 mg harpagoside/day) for 8 weeks. Symptoms improved and the dose of co-medication (NSAIDs) could be reduced. | 2001 | Schendel [514] |

| DJD | OT 675 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (~30 mg harpagoside/day) for 8 weeks. Efficacy rated good or very good in 82% of cases. The symptom scores decreased, and co-medication was successfully reduced or even discontinued. | 2001 | Ribbat and Schakau [515] |

| MSD | OT 250 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (60 mg harpagoside/day) for 8 weeks. Both generic and disease-specific outcome measures improved. | 2002 | Chrubasik et al. [516] |

| DJD | OT 614 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (480 mg twice daily) for 8 weeks. Symptoms improved in the majority of patients; treatment was well-tolerated. | 2003 | Kloker and Flammersfeld [517,518] |

| DJD | OT 75 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (50 mg harpagoside/day) for 12 weeks. WOMAC index and 10 cm VAS pain scale improved notably. | 2003 | Wegener and Lüpke [519,520] |

| MSD | OT 99 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (~30 mg harpagoside/day) for 6 weeks. Symptoms improved. | 2005 | Rütten and Kuhn [521] |

| MSD | OT 102 (29/22/51) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (~30 mg harpagoside/day) and/or conventional therapy for 6 weeks. Efficacy was found in all groups, advantages for devil’s claw were not statistically significant. | 2005 | Schmidt et al. [522,523] |

| DJD | OT 65 | Patients treated with combination of Harpagophytum procumbens, Zingiber officinale, and Urtica sp. (ratio not disclosed) for 8 weeks. Improvements in all efficacy parameters were observed. | 2005 | Sohail et al. [524] |

| Endometriosis | OT 6, 12 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (1600 mg daily) for 12 weeks. Reduction of symptoms in 4 (6) patients after 4 weeks, in all patients after 12 weeks. | 2005, 2006 | Arndt et al. [525,526] |

| DJD | OT 259 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (1.5–3:1, 960 mg daily) and NSAIDs for 8 weeks. At the end of the treatment, 44.8% could decrease NSAID dosage. All parameters improved significantly. | 2006 | Suter et al. [527,528] |

| MSD | OT 114 | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (60 mg harpagoside/day) for up to 54 weeks. Most outcome scores improved significantly over time. | 2007 | Chrubasik et al. [529] |

| DJD | OT 42 | Patients treated with combination of Harpagophytum (1800 mg), Curcuma longa (1200 mg), and bromelain (900 mg) daily, plus conventional therapies for 2 weeks. Clinically relevant improvement of joint pain scores in all patients. | 2014 | Conrozier et al. [530] |

| DJD | OT 20 | Patients treated with combination of 500 mg glucosamine sulfate, 400 mg chondroitin sulfate, 10 mg collagen type II, and 40 mg Harpagophytum per day for 12 months. Femoral hyaline cartilage thickness significantly improved and radiographic progression of knee osteoarthritis delayed. | 2019 | Vreju et al. [531] |

| MSD | OT 39/40/16 | Otherwise healthy subjects with mild/moderate neck/shoulder pain related to sport; cream containing a combination of ingredients, including H. procumbens root extract + standard treatment, standard treatment, diclofenac patch + standard treatment respectively, for 2 weeks; significant improvement in pain, stiffness, mobility, and working capacity, compared to non-cream groups. | 2021 | Hu et al. [532] |

CP = chronic polyarthritis; IA = intra-articular; SC = subcutaneous; DJD = degenerative joint diseases (osteoarthritis); MSD = musculo-skeletal disorders (low back pain); OT = observational trial; O = observation; CR = case report; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities.

Table 11.

RCTs conducted between 1980 and 2017.

Table 11.

RCTs conducted between 1980 and 2017.

| DJD | RCT 39 | 400 mg Harpagophytum extract (not specified), and 25 mg diclofenac, or placebo 3× daily for 6 months. Overall confirmation of anti-inflammatory effects without side effects. | ~1980 | Chaouat, cited in [66,67] |

| DJD | RCT 50 (25/25) | Harpagophytum extract (<30 mg harpagoside/day) and phenybutazone (300 mg per day for the first four days, then 200 mg) respectively, for 28 days. Devil’s claw found equally effective to phenybutazone. | 1980 | Schrüffler [533] |

| DJD | RCT 50 (25/25) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (<20 mg harpagoside/day) or placebo for three weeks showed a significant decrease in pain severity vs. placebo. | 1984 | Guyader [534] |

| DJD | RCT 100 (50/50) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (60 mg harpagoside/day) or placebo for 30 days. Only 6 patients in the verum group still experienced moderate pain vs. 32 in the placebo group. | 1990 | Pinget and Lecomte [535] |

| DJD | RCT 89 (45/44) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (60 mg harpagoside/day) or placebo for two months. Significant decrease in severity of pain and significant increase in spinal and cofexomoral mobility vs. placebo. | 1992 | Lecomte and Costa [536] |

| MSD | RCT 118 (59,59) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (50 mg harpagoside/day) or placebo for 4 weeks. Treatment group used less analgesics, had greater improvement in median Arhus scores (20% vs. 8%; p < 0.059), and had more patients pain-free at the end (9/51 vs. 1/54; p = 0.008). | 1996 | Chrubasik et al. [537,538,539] |

| MSD | RCT 109 (54/55) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (50 mg harpagoside/day) or placebo for 4 weeks. Rescue medication: tramadol. Significant improvement in Arhus index and pain index, and co-medication reduced vs. placebo. | 1997 | Chrubasik et al. [540] |

| DJD | RCT 100 (50/50) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (30 mg harpagoside/day) or placebo for 30 days. Favorable effects were evident after 10 days vs. placebo. | 1997 | Schmelz and Hämmerle [541] |

| MSD | RCT 197 (65/66/66) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (50 mg (1), 100 mg (2) harpagoside/day) or placebo (3) for four weeks. 6, 10, and 3 patients were pain-free in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Arhus index score decreased but not statistically significant. Dose-related effect not confirmed. | 1999 | Chrubasik et al. [542] |

| DJD | RCT 122 (62/60) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (57 mg harpagoside/day) or diacerhein at 100 mg daily for four months. Results showed significant improvement in both groups at a similar rate. | 2000 | Chantre et al. [543,544] |

| MSD | RCT 63 (31/32) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (~30 mg harpagoside/day) or placebo for 4 weeks. Significant efficacy for visual analogue scale, pressure algometer test, muscle stiffness test, and muscular ischemia test. No differences to placebo in anti-nociceptive muscular reflexes or electromyogram activity. | 2000 | Göbel et al. [512,513,545,546] |

| DJD | RCT 46 (24/22) | Patients treated with ibuprofen (800 mg) and Harpagophytum extract (~30 mg harpagoside/day) or placebo for 20 weeks. WOMAC scores decreased similarly, but during an ibuprofen-free period, symptoms worsened less than 20% for 71% of devil’s claw patients vs. 41% of placebo patients. | 2001 | Frerick et al. [547] |

| DJD | RCT 78 (39/39) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (~30 mg harpagoside/day) or placebo for 20 weeks. Co-medication ibuprofen. Symptoms improved similarly for both groups. | 2002 | Biller [548] |

| MSD | RCT 88 (44/44) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (60 mg harpagoside/day) for 6 weeks or 12.5 mg/day of rofecoxib. Outcome scores improved similarly for both groups. Follow-up confirmed the results of the pilot study. | 2003 | Chrubasik et al. [538,539,549,550,551,552] |

| MSD | RCT 97 (36/31/30) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (~30 mg harpagoside/day) or NSAID (Voltaren 150 mg or Vioxx 12.5 mg), duration not provided; outcomes show equality of treatment. | 2005 | Lienert et al. [553,554] |

| DJD | RCT 60 (30/30) | Patients treated with combination of Harpagophytum and Apium graveolens extract (cream, 1.5 cm, twice daily) or placebo for 2 weeks. Treatment group showed significant improvement in algometer, flexion, and extension readings. | 2006 | Pillay [555] |

| Sore throat after tracheal intubation | RCT 60 (30/30) | Patients treated with Harpagophytum extract (480 mg one hour before intubation) or placebo plus premedication (fentanyl, midazolam, propofol). No significant difference was observed between groups. | 2016 | Anvari et al. [556] |

| DJD | RCT 92 (46/46) | Patients treated with combination of Rosa canina, Urtica sp., Harpagophytum procumbens, and vitamin D (20.0 g puree and 4.0 g juice concentrate, 160 mg dry extract, 108 mg dry extract, 5 µg, respectively) or placebo for 12 weeks. WOMAC and quality of life scores significantly improved vs. placebo. | 2017 | Moré et al. [557] |

DJD = degenerative joint diseases (osteoarthritis); MSD = musculo-skeletal disorders (low back pain); RCT = randomized controlled trial; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities.

12.2. Safety

A broad spectrum of claims regarding the safety of Harpagophytum in clinical practice can be found in the literature, ranging from unsubstantiated cautioning against its use altogether [215,558] to overly optimistic perspectives in the lay press. The truth, as it often does, lies somewhere in between.

12.2.1. Clinical Safety

Short- and long-term use (on average 30–60 days, in several long-term studies up to 54 weeks) have been described as safe and well-tolerated, and the most reported adverse events in clinical investigations were of mild gastrointestinal nature [559]. These may be related to its anticholinesterase effect in vitro [318,366]. A review of the safety of Harpagophytum preparations [560] concluded that they are likely to be safe with only few and no serious adverse events observed, however, it was also established that further, more rigorous safety investigations are required [561], especially considering that the dosage in most studies was found at the lower limit, and for the recommended long-term use.

12.2.2. Interaction Potential

Harpagophytum was found to be a weak inhibitor of CYP 1A2 and CYP 2D6, and a moderate inhibitor of CYP 2C8, CYP 2C9, CYP 2C19, and CYP 3A4 in vitro [397,399,400,562], however, clinical relevance is unlikely [402]. Increased anticoagulant effects have been reported with concurrent anticoagulant use [563,564,565,566,567]. While an interaction is possible, evidence is inconclusive [568] and has only been demonstrated in vitro. Herb–drug interactions and interference with anticoagulants are hypothetical and have not been conclusively demonstrated.

12.2.3. Adverse Event Reports

A case of hyponatremia in a patient with systemic hypertension has been associated with Harpagophytum (co-medications were losartan, clonidine, omeprazole, and simvastatin) [569]. Another case report suggests development of grade 2 symptomatic hypertension in a normotensive woman during self-administration of Harpagophytum [570]. However, available data do not suggest interaction potential with conventional antihypertensives at recommended doses (animal studies demonstrating a hypotensive effect used much higher doses). A case-controlled surveillance study has associated Harpagophytum with a pancreatoxic potential [571]. One early case report points at a potential allergic reaction after professional exposure to Harpagophytum [572]. Rahman and colleagues [573] included Harpagophytum in a review of botanicals with drug-interaction potential in the elderly with inflammatory bowel disease, however, did not present any causality that would justify concern.

12.2.4. Side Effects

Considering the size of the total patient collective from all clinical investigations listed in Section 11.1. (>11,000), and the most common side effects being mild gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea), CNS disorders (dizziness, headache), and allergic skin reactions, the aforementioned case reports should be further investigated, but, until corroborated by new data, their clinical relevance can be deemed as limited.

12.2.5. Pregnancy and Lactation

In Vitro data suggest spasmogenic and uterotonic effects in mammalian uterine muscles [412,413]. In the absence of adequate in vivo data [408,409], use during pregnancy and lactation should be cautioned.

13. Veterinary Applications

Veterinary applications of devil’s claw have received increased attention and gained popularity over the last 15 years, with focus on equines and canines. Colas and colleagues [250,255,256,574] provided methods for detection and control of iridoid glucosides from Harpagophytum in horse urine. Torfs et al. [575] discussed the potential benefits of devil’s claw products in veterinary practice and cited one study conducted by Montavon [576] in which ten horses with tarsal osteoarthritis were treated with an herbal powder mix containing Harpagophytum (20 g total) and smaller quantities of Ribes nigrum, Equisetum arvense, and Salix alba for 10 days a month over three consecutive months. The control group received 2 g of phenylbutazone daily. Locomotor scores improved significantly with the test medication vs. conventional NSAID. However, study results are of limited reliability due to size, lack of blinding, and subjective assessment. Axmann and colleagues [577,578] investigated pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of a Harpagophytum extract in horses. They provided a method with which they were able to detect harpagoside in plasma for up to 9 h after administration. Efficacy was investigated in a RCT design with 40 horses (20/20), the study medication was 10 g daily of an aqueous Harpagophytum extract (25.3% harpagoside) or placebo for 8 weeks, and a follow-up after 16 weeks. Locomotor abnormalities were assessed on a treadmill with an optoelectronic motion capture system, and follow-up was conducted via questionnaires. While the objective motion assessment did not yield significant differences between baseline and the end of the study, evaluation of the questionnaires reflected significant improvements and a “lingering” effect in the subjective assessment.

Moreau and colleagues [579] investigated the efficacy of Harpagophytum (harpagoside > 2.7%) as part of a complex mixture of ingredients for improving symptoms of canine osteoarthritis in a RCT with 32 dogs (16 per group) over 8 weeks. The primary endpoint, peak vertical force, was significantly higher in treated dogs vs. placebo after 4 and 8 weeks, and clinical signs overall improved with treatment.

Ethnoveterinary uses of devil’s claw have also been recorded. Moreki [113] reports on ethnoveterinary practices in Botswana to include the use of a decoction of Harpagophytum in poultry.

A reliable body of clinical data confirming the efficacy of Harpagophytum in veterinary applications is clearly lacking but is needed to better exploit the potential benefits. In this context, it must be noted that the use of devil’s claw—just like other analgesics—is highly restricted in equestrian sport. Harpagoside is included in the “Equine Prohibited Substance List” of the Federation Equestre Internationale as a “controlled medication”, the use of which is prohibited during training and competitions. Curiously, harpagoside is not included in the very same organization’s “List of Detection Times”, leaving horse owners in the dark as to when to discontinue use prior to a tournament. This lack of clarity may further hamper more prolific use in veterinary practice.

14. Patents

As mentioned in Section 10, the majority of patents refer to processing methods, specifically extraction and dosage forms, which constitute the only legitimately patentable intellectual property for the pharmaceutical industry, except in cases where new effects or combinations, not previously described in ethnobotanical use accounts, were elucidated. It is noteworthy that most of the earlier patents listed below in Table 12 (pre-2000) have expired or been withdrawn. Pending patents have been excluded.

Table 12.

Patents pertaining to Harpagophytum and its preparations.

15. Discussion and Conclusions

Devil’s claw is a well-established phytopharmaceutical. A large body of data exists in which composition, pharmacological activities, and clinical effects are elucidated, and in turn support and affirm traditional use applications. Nonetheless, several aspects requiring further investigation were highlighted by this review.

Revision of the genus to account for introgression, geographical, and biochemical variation, and geo-authenticity is needed.

In view of the interchangeable use of both Harpagophytum species and mixtures thereof in clinical practice, further comparative examination of the composition of both species is needed. Verbascoside as an anti-inflammatory compound present in Harpagophytum could be an interesting target of future research.

Despite some inconsistent outcomes and contradictory results, pharmacological evidence appears to be overall sufficient to support clinical use. Sufficient pharmacological differentiation between Harpagophytum species, however, is lacking.

Toxicological evaluations of Harpagophytum indicate a low toxicity in animal models. While genotoxicity testing is part of the regulatory requirements for the market authorization of herbal medicinal products in Europe, results are proprietary (product-related) and have not been published. Adequate tests on reproductive toxicity, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity, performed according to currently valid OECD guidelines, need to be made publicly available.

While there may be strong clinical evidence that devil’s claw preparations are effective in the treatment of degenerative joint diseases and musculoskeletal disorders in principle, this conclusion cannot be extended to specific preparations, because of the varying pharmaceutical quality of individual preparations.

Further investigations are required (a) to identify the therapeutically active substances or fractions and thus enable tests which (b) use accordingly standardized and sufficiently dosed preparations with a carefully designed setup and methodology in order to obtain quantifiable results for the efficacy of devil’s claw preparations. These need to be conducted with both Harpagophytum spp. individually but prepared identically. Trial designs should be guided by the recommendations of the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Specifically, both species could be compared in a two-arm cross-over design. Conventional medication could be added as a third arm to assess comparative efficacy. Studies should be of adequate power, randomized, placebo-controlled, and double-blinded. Problematic in an ethical sense is the denial of “first aid” medication in placebo-controlled studies, permission of which would confound outcomes. Outcomes should be objective or at least a combination of objective and subjective measures.

Further research is also warranted in the area of clinical safety, specifically with regard to the drug interaction potential of devil’s claw preparations. Until then, safety considerations as expressed in current compendia, e.g., [15], should be considered appropriate.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data has been presented in the main text.

Acknowledgments

Ernst Schneider, Mathias Schmidt, Sigrun Chrubasik, Margret Moré, Dave Cole, Josef Brinckmann, Wolfram Hartmann, Cyril Lombard, Ben-Erik van Wyk, and Karen Nott kindly assisted with the procurement of some illusive publications.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ihlenfeldt, H.-D.; Hartmann, H. Die Gattung Harpagophytum (Burch.) DC. Ex Meissn. (Monographie der afrikanischen Pedaliaceae II). Hambg. Staatsinst. Allg. Bot. Mitt. 1970, 13, 15–69. [Google Scholar]

- Muzila, M.; Werlemark, G.; Ortiz, R.; Sehic, J.; Fatih, M.; Setshogo, M.; Mpoloka, W.; Nybom, H. Assessment of diversity in Harpagophytum with RAPD and ISSR markers provides evidence of introgression. Hereditas 2014, 151, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendler, T.; van Wyk, B.E. A historical, scientific and commercial perspective on the medicinal use of Pelargonium sidoides (Geraniaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stander, M.A.; Brendler, T.; Redelinghuys, H.; Van Wyk, B.E. The commercial history of Cape herbal teas and the analysis of phenolic compounds in historic teas from a depository of 1933. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 76, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C.H. Different histories of buchu: Euro-American appropriation of San and Khoekhoe knowledge of buchu plants. Environ. Hist. 2007, 13, 333–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendler, T.; Cock, I.E. A short history of Cape aloe bitters. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Helmstädter, A. Xysmalobium undulatum (Uzara) research—How everything began. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 164, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brendler, T. The rise and fall of Hoodia: A lesson on the art and science of natural product commercialization. In African Natural Plant Products, Volume III: Discoveries and Innovations in Chemistry, Bioactivity, and Applications; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 313–324. ISBN 1947-5918. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, B.E. A review of commercially important African medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 176, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CITES. Inclusion of Harpagophytum Procumbens in Appendix II in Accordance with Article II 2(a) and Inclusion of Harpagophytum Zeyheri in Appendix II in Accordance with Article II 2(b) for Reasons of Look-Alike Problems. 2000, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/cop/11/prop/60.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Czygan, F.-C.; Krüger, A.; Schier, W.; Volk, O.H. Pharmazeutisch-biologische Untersuchungen der Gattung Harpagophytum (Bruch.) DC ex Meissn. 1. Mitteilung: Phytochemische Standardisierung von Tubera Harpagophyti. Dtsch. Apoth. Ztg. 1977, 117, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Eich, J.; Schmidt, M.; Betti, G.J.R. HPLC analysis of iridoid compounds of Harpagophytum taxa: Quality control of pharmaceutical drug material. Pharm. Pharmacol. Lett. 1998, 8, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Feistel, B.; Gaedcke, F. Analytical identification of Radix Harpagophyti procumbentis and zeyheri. Z. Phytother. 2000, 21, 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Nott, K. A Survey of the Harvesting and Export of Harpagophytum procumbens and Harpagophytum Zeyheri in SWA/Namibia; Etosha Ecological Institute: Okaukuejo, Namibia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- EMA. European Union Herbal Monograph on Harpagophytum procumbens DC. and/or Harpagophytum zeyheri Decne., Radix. EMA/HMPC/627057/2015; Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC): London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy. Harpagophyti radix. In ESCOP Monographs, 2nd ed.; Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2003; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Menghini, L.; Recinella, L.; Leone, S.; Chiavaroli, A.; Cicala, C.; Brunetti, L.; Vladimir-Knezevic, S.; Orlando, G.; Ferrante, C. Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) and chronic inflammatory diseases: A concise overview on preclinical and clinical data. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2152–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, K.M.; Cole, D. The commercial harvest of devil’s claw (Harpagophytum spp.) in southern Africa: The devil’s in the details. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdikian, B.; Lanhers, M.C.; Fleurentin, J.; Ollivier, E.; Maillard, C.; Balansard, G.; Mortier, F. An analytical study, anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of Harpagophytum procumbens and Harpagophytum zeyheri. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Harpagophytum procumbens (devil’s claw). Altern. Med. Rev. 2008, 13, 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J. Charms & harms: Devil’s claw. J. Prim. Health Care 2009, 1, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprasse, M. Description, identification et usages thérapeutiques de la «griffe du diable»: Harpagophytum procumbens DC. J. Pharm. Belg. 1980, 35, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Chrubasik, S. Wirksamkeit pflanzlicher Schmerzmittel am Beispiel des Teufelskrallenwurzelextrakts. Orthopäde 2004, 33, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czygan, F.-C. Harpago- oder Teufelskrallentee, das Auf und Ab einer Modedroge. Z. Phytother. 1984, 5, 922–925. [Google Scholar]

- Czygan, F.-C. Nochmals Harpagophytum. Z. Phytother. 1984, 5, 972. [Google Scholar]

- Czygan, F.-C. Portrait einer Arzneipflanze: Harpagophytum—Teufelskralle. Z. Phytother. 1987, 8, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich, C. Harpagophytum procumbens DC. Österr. Apoth. Ztg. 1974, 28, 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Esdorn, I. Afrikanische Reiseeindrücke in pharmazeutischer und kultureller Hinsicht. Dtsch. Apoth. Ztg. 1963, 103, 785–789. [Google Scholar]

- Faivre, C.; Ghedira, K.; Goetz, P.; Lejeune, R. Harpagophytum procumbens (Pedaliaceae). Phytothérapie 2007, 5, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, M.; Ivanovska, N.; Alipieva, K.; Dimitrova, P.; Verpoorte, R. Harpagoside: From Kalahari Desert to pharmacy shelf. Phytochemistry 2013, 92, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C. Arzneistoff Porträt—Die Afrikanische Teufelskralle—Voodoo oder wirksames Arzneimittel? Dtsch. Apoth. Ztg. 2000, 140, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspersen-Schib, R. Harpagophyti radix—Wirklich eine Wunderdroge. Dtsch. Apoth. Ztg. 1990, 130, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Kampffmeyer, H. Teufelskralle—Gibt es eine therapeutische Wirkung? ZFA 1980, 56, 618. [Google Scholar]

- Kannacher, M. Harpagophytum procumbens—Die Teufelskralle. Tubera harpagophyti, die Speicherknollen. Volksheilkunde 1993, 45, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Lis, K. Diabelska moc czarciego pazura. Reumatologia 2010, 48, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, G.; Fiebich, B.; Wartenberg, A.; Brien, S.; Lewith, G.; Wegener, T. Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens): An anti-inflammatory herb with therapeutic potential. Phytochem. Rev. 2005, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, G.P. Harpagophytum procumbens—Traditional anti-inflammatory herbal drug with broad therapeutic potential. In Herbal Drugs: Ethnomedicine to Modern Medicine; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Miraldi, E.; Biagi, M.; Giachetti, D. A comprehensive systematic pharmacological review on Harpagophytum procumbens DC. (Devil’s claw). Biol. Sci. PJSIR 2008, 51, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Mncwangi, N.; Chen, W.; Vermaak, I.; Viljoen, A.; Gericke, N. Devil’s claw—A review of the ethnobotany, phytochemistry and biological activity of Harpagophytum procumbens. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 755–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, D.K. The Ethnobotany and Chemistry of South African Traditional Tonic Plants. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2012; p. 481. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, T. Gut beraten mit Teufelskralle? Z. Phytother. 2001, 22, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S. Die antiarthritische Wirkung der Harpagophytum-Wurzel. Österr. Apoth. Ztg. 1971, 25, 829. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S. Rheumatherapie mit Harpagophytum. Therapiewoche 1972, 22, 1072–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S. Teufelskralle und Rheuma. Österr. Apoth. Ztg. 1983, 37, 111–113. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, H. Die Wurzel aus dem roten Sand. Kosmos 1977, 73, 122–124. [Google Scholar]