DNA Methylation Profiling for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Patients with Nontuberculous Mycobacterium Lung Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. DNA Extraction and Methylation Microarray

2.3. Merged Public Data Set

2.4. Bioinformatic Analysis and Visualization

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics

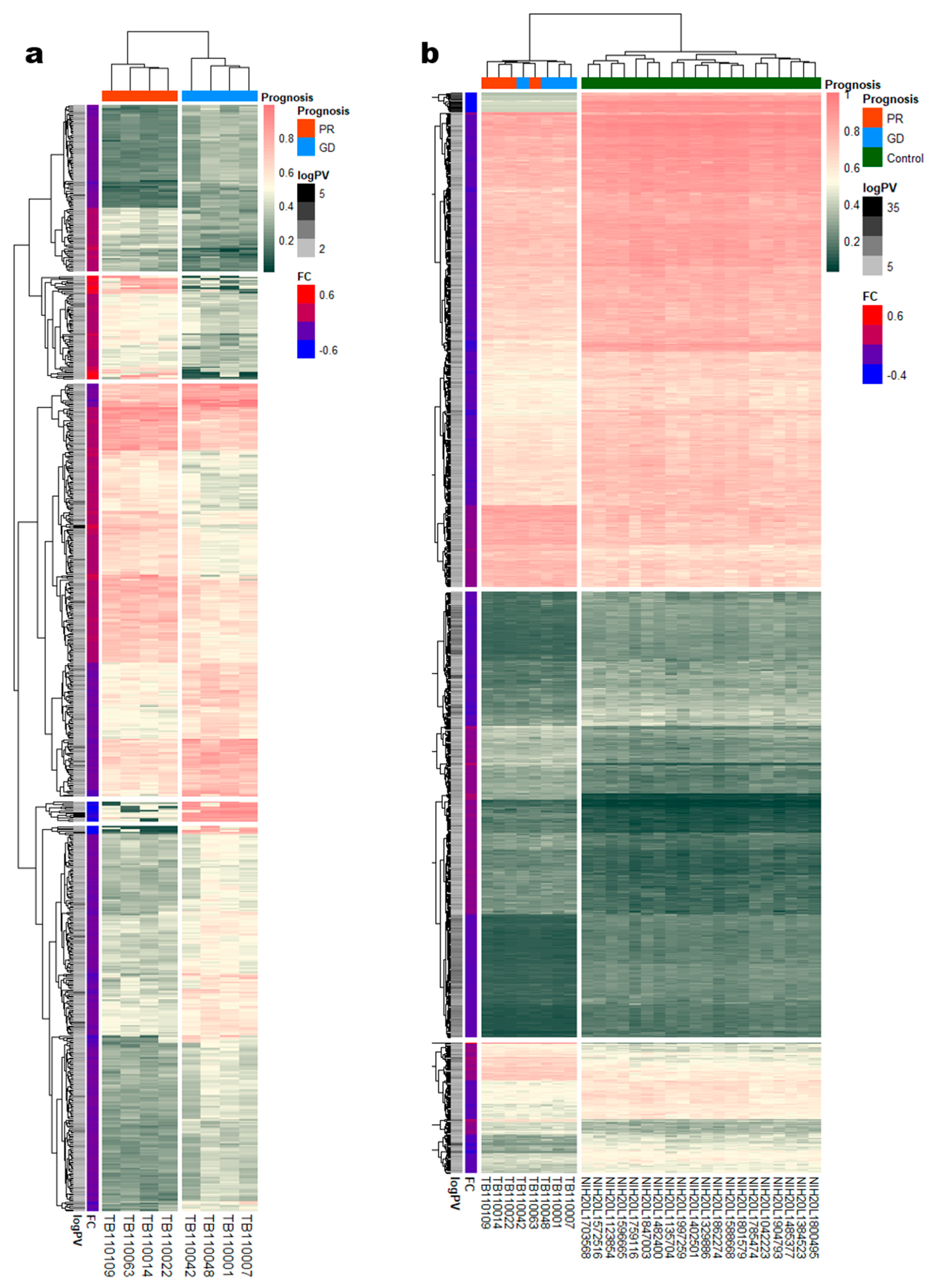

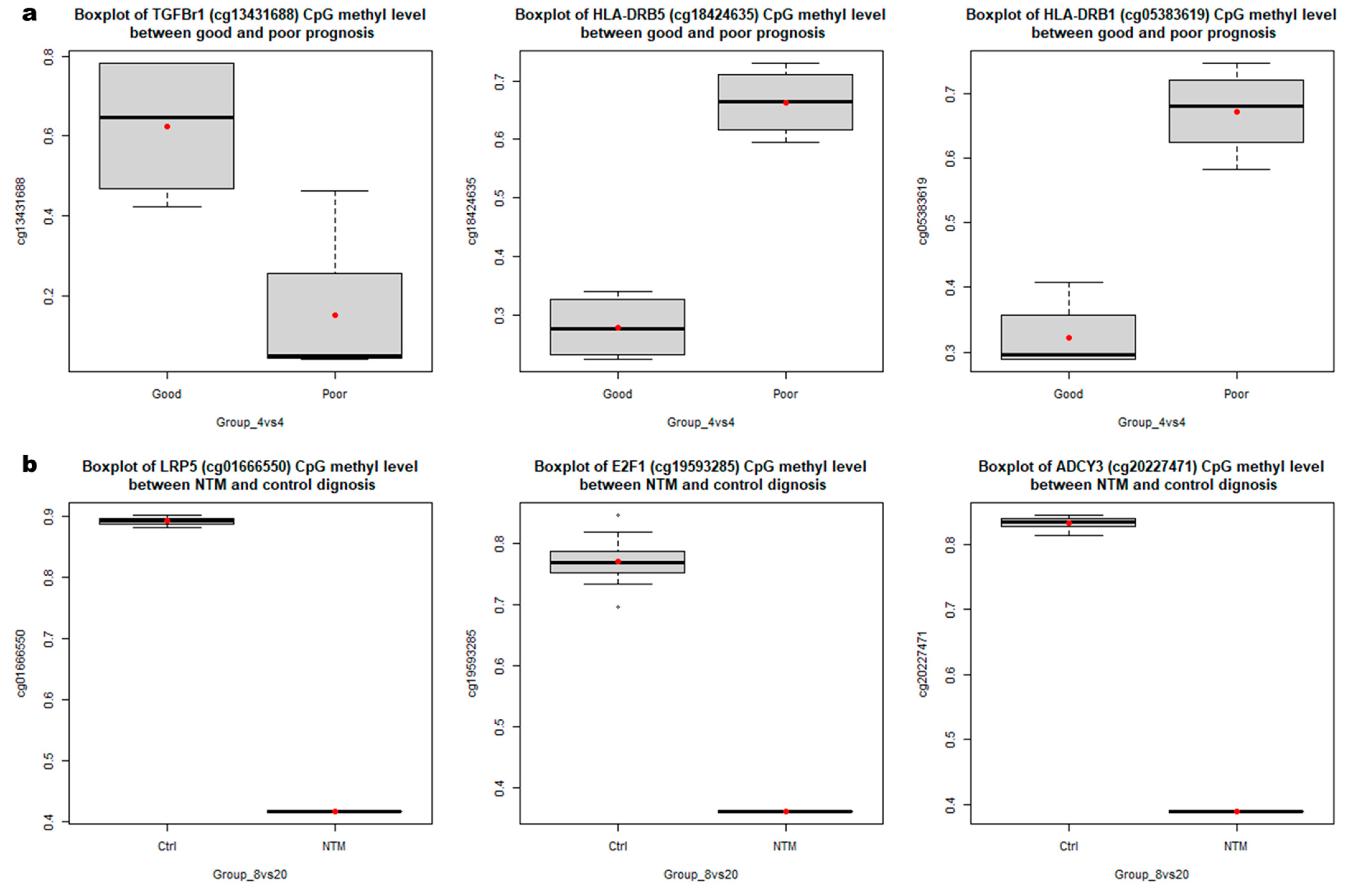

3.2. Identification of DMRs According to NTM Prognoses and between Patients and Healthy Controls

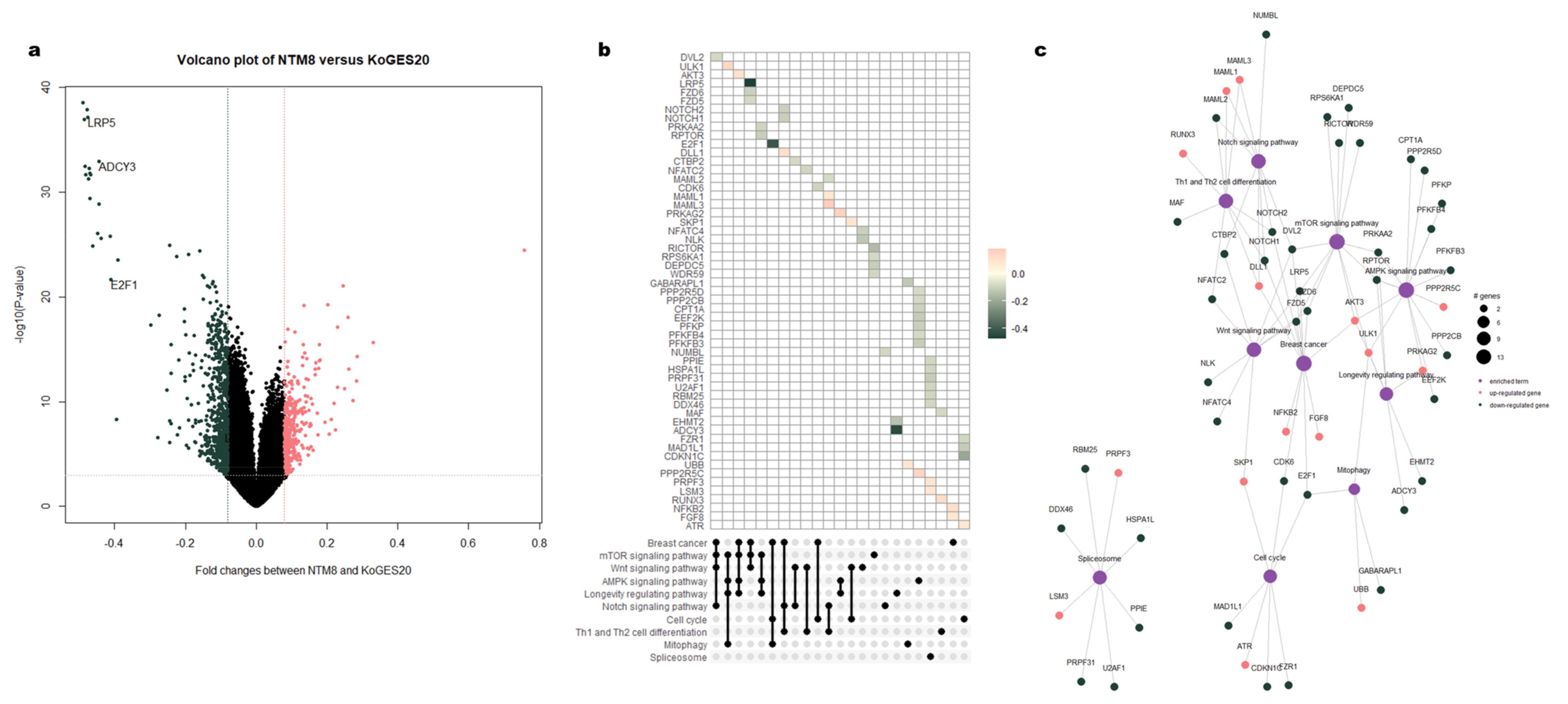

3.3. Functional Enrichment Analysis of DMRs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haworth, C.S.; Banks, J.; Capstick, T.; Fisher, A.J.; Gorsuch, T.; Laurenson, I.F.; Leitch, A.; Loebinger, M.R.; Milburn, H.J.; Nightingale, M.; et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmo-nary disease (NTM-PD). Thorax 2017, 72, ii1–ii64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeon, D. Infection Source and Epidemiology of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Lung Disease. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2019, 82, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, C.M.; Gomes, M.S.; Silva, T. Looking beyond Typical Treatments for Atypical Mycobacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- To, K.; Cao, R.; Yegiazaryan, A.; Owens, J.; Venketaraman, V. General overview of nontuberculous mycobacteria opportunistic pathogens: Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium abscessus. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.-C.; The TAMI Group; Lee, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-L.; Wang, J.-Y.; Yu, C.-J.; Lee, L.-N. Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Lung Disease with Different Radiographic Patterns. Lung 2011, 189, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ingen, J.; Aksamit, T.; Andrejak, C.; Böttger, E.C.; Cambau, E.; Daley, C.L.; Griffith, D.E.; Guglielmetti, L.; Holland, S.M.; Huitt, G.A.; et al. Treatment outcome definitions in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: An NTM-NET con-sensus statement. Eur. Respir. Soc. 2018, 51, 1800170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griffith, D.E.; Aksamit, T.R. Therapy of refractory nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 25, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.-S.; Koh, W.-J.; Daley, C.L. Treatment ofMycobacterium aviumComplex Pulmonary Disease. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2019, 82, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, C.L.; Iaccarino, J.M.; Lange, C.; Cambau, E.; Wallace, R.J., Jr.; Andrejak, C.; Böttger, E.C.; Brozek, J.; Griffith, D.E.; Guglielmetti, L.; et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: An official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, e1–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidsley, R.; Zotenko, E.; Peters, T.J.; Lawrence, M.G.; Risbridger, G.P.; Molloy, P.; Van Djik, S.; Muhlhausler, B.; Stirzaker, C.; Clark, S.J. Critical evaluation of the Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip microarray for whole-genome DNA methylation profiling. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dinardo, A.R.; Rajapakshe, K.; Nishiguchi, T.; Grimm, S.L.; Mtetwa, G.; Dlamini, Q.; Kahari, J.; Mahapatra, S.; Kay, A.W.; Maphalala, G.; et al. DNA hypermethylation during tuberculosis dampens host immune responsiveness. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 3113–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shell, S.S.; Prestwich, E.G.; Baek, S.-H.; Shah, R.R.; Sassetti, C.M.; Dedon, P.; Fortune, S.M. DNA Methylation Impacts Gene Expression and Ensures Hypoxic Survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heyn, H.; Esteller, M. DNA methylation profiling in the clinic: Applications and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansell, G.; Gorrie-Stone, T.J.; Bao, Y.; Kumari, M.; Schalkwyk, L.S.; Mill, J.; Hannon, E. Guidance for DNA methylation studies: Statistical insights from the Illumina EPIC array. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bansal, A.; Pinney, S.E. DNA methylation and its role in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2017, 18, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samblas, M.; Milagro, F.I.; Martínez, A. DNA methylation markers in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and weight loss. Epigenetics 2019, 14, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovenden, E.S.; McGregor, N.W.; Emsley, R.A.; Warnich, L. DNA methylation and antipsychotic treatment mechanisms in schizophrenia: Progress and future directions. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 81, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montrose, L.; Ward, T.J.; Semmens, E.O.; Cho, Y.H.; Brown, B.; Noonan, C.W. Dietary intake is associated with respiratory health outcomes and DNA methylation in children with asthma. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2017, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, M.; Wang, L.; Wu, T.; Xi, J.; Han, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, D.; Fang, Q.; Tang, B. NLRP3 Activation Was Regulated by DNA Methylation Modification duringMycobacterium tuberculosisInfection. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shu, C.-C.; Pan, S.-W.; Feng, J.-Y.; Wang, J.-Y.; Chan, Y.-J.; Yu, C.-J.; Su, W.-J. The Clinical Significance of Programmed Death-1, Regulatory T Cells and Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells in Patients with Nontuberculous Mycobacteria-Lung Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iwata, K.; Oka, S.; Tsuno, H.; Furukawa, H.; Shimada, K.; Hashimoto, A.; Komiya, A.; Tsuchiya, N.; Katayama, M.; Tohma, S. Biomarker for nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Anti-glycopeptidolipid core antigen immunoglobulin A antibodies. Mod. Rheumatol. 2018, 28, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.E.; Aksamit, T.; Brown-Elliott, B.A.; Catanzaro, A.; Daley, C.; Gordin, F.; Holland, S.M.; Horsburgh, R.; Huitt, G.; Iademarco, M.F.; et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 367–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Han, B.G.; KoGES Group. Cohort profile: The Korean genome and epidemiology study (KoGES) consortium. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulgen, E.; Ozisik, O.; Sezerman, O.U. pathfindR: An R Package for Comprehensive Identification of Enriched Pathways in Omics Data Through Active Subnetworks. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Chen, Z.W. The crucial roles of Th17-related cytokines/signal pathways in M. tuberculosis infection. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jo, E.-K.; Silwal, P.; Yuk, J.-M. AMPK-Targeted Effector Networks in Mycobacterial Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmandas, E.; Beigier-Bompadre, M.; Cheng, S.C.; Kumar, V.; van Laarhoven, A.; Wang, X.; Ammerdorffer, A.; Boutens, L.; de Jong, D.; Kanneganti, T.D.; et al. Rewiring cellular metabolism via the AKT/mTOR pathway contributes to host de-fence against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human and murine cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016, 46, 2574–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, M.; Sun, J.; Ma, Y.; Ren, Z.; Tian, Z.; et al. Transcription factor E2F1 sup-presses dendritic cell maturation. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 6084–6091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villaseñor, T.; Madrid-Paulino, E.; Maldonado-Bravo, R.; Urbán-Aragón, A.; Pérez-Martínez, L.; Pedraza-Alva, G. Activation of the Wnt Pathway by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A Wnt–Wnt Situation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, J.; Reiling, N. The Wnt Blows: On the functional role of Wnt signaling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and beyond. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lam, A.P.; Herazo-Maya, J.D.; Sennello, J.A.; Flozak, A.S.; Russell, S.; Mutlu, G.M.; Budinger, G.R.S.; DasGupta, R.; Varga, J.; Kaminski, N.; et al. Wnt CoreceptorLrp5Is a Driver of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.W.; Wu, L.S.H.; Huang, G.M.; Huang, K.Y.; Lee, T.Y.; Weng, J.T.Y. Gene expression profiling identifies candidate bi-omarkers for active and latent tuberculosis. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, S.A.; Jhun, B.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Moon, S.M.; Yang, B.; Kwon, O.J.; Daley, C.L.; Shin, S.J.; Koh, W.J. miRNA expression pro-files and potential as biomarkers in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jati, S.; Sarraf, T.R.; Naskar, D.; Sen, M. Wnt Signaling: Pathogen Incursion and Immune Defense. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, H.; Sherman, J.; Tary-Lehman, M.; Toossi, Z. Analysis of transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) expression in human monocytes infected with Mycobacterium avium at a single cell level by ELISPOT assay. J. Immunol. Methods 2002, 259, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D. Transforming growth factor β: A central modulator of pulmonary and airway inflammation and fibrosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2006, 3, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermudez, L.E. Production of transforming growth factor-beta by Mycobacterium avium-infected human macrophages is as-sociated with unresponsiveness to IFN-gamma. J. Immunol. 1993, 150, 1838–1845. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yao, Y.; Xiong, J.; Wu, J.; Tang, X.; Li, G. Evaluation of the Inflammatory Response in Macrophages Stimulated with Exosomes Secreted byMycobacterium avium-Infected Macrophages. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuyama, M.; Ishii, Y.; Yageta, Y.; Ohtsuka, S.; Ano, S.; Matsuno, Y.; Morishima, Y.; Yoh, K.; Takahashi, S.; Ogawa, K.; et al. Role of Th1/Th17 Balance Regulated by T-bet in a Mouse Model of Mycobacterium avium Complex Disease. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 1707–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuyama, M.; Ishii, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Ano, S.; Morishima, Y.; Yoh, K.; Takahashi, S.; Ogawa, K.; Hizawa, N. Overexpression of RORγt Enhances Pulmonary Inflammation after Infection with Mycobacterium Avium. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Koh, W.J.; Park, H.; Jeon, K.; Kwon, O.; Cho, S.N.; Shin, S.J. Changes in serum immunomolecules during antibiotic therapy for Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 176, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philley, J.V.; Hertweck, K.L.; Kannan, A.; Brown-Elliott, B.A.; Wallace, R.J.; Kurdowska, A.; Ndetan, H.; Singh, K.P.; Miller, E.J.; Griffith, D.E.; et al. Sputum Detection of Predisposing Genetic Mutations in Women with Pulmonary Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| NTM n = 8 | HC n = 20 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.1 ± 11.2 | 65.5 ± 5.4 |

| Sex, male | 5 (62.5) | 13 (65) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.7 ± 3.7 | 20.5 ± 1.0 |

| Smoker | 2 (25) | 8 (40) |

| Alcohol | 2 (25) | 3 (15) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| HTN | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| DM | 2 (25) | 0 (0) |

| COPD/Asthma | 2 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Heart failure | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, J.Y.; Ko, Y.K.; Gim, J.-A. DNA Methylation Profiling for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Patients with Nontuberculous Mycobacterium Lung Disease. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 43, 501-512. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb43020038

Oh JY, Ko YK, Gim J-A. DNA Methylation Profiling for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Patients with Nontuberculous Mycobacterium Lung Disease. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2021; 43(2):501-512. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb43020038

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Jee Youn, Young Kyung Ko, and Jeong-An Gim. 2021. "DNA Methylation Profiling for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Patients with Nontuberculous Mycobacterium Lung Disease" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 43, no. 2: 501-512. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb43020038