Abstract

Background and objectives: Improved quality of life (QoL) and life expectancy of elderly diabetic patients revolves around optimal glycemic control. Inadequate glycemic control may lead to the development of diabetes-associated complications (DAC), which not only complicate the disease, but also affect morbidity and mortality. Based on the available literature, the aim was to elucidate the vicious cycle underpinning the relationship between diabetes complications and glycemic control. Materials and Methods: A comprehensive literature search was performed to find eligible studies published between 1 January 2000 and 22 September 2018 pertaining to diabetes complications and glycemic control. Results: Initially, 261 studies were retrieved. Out of these, 67 were duplicates and therefore were excluded. From the 194 remaining articles, 85 were removed based on irrelevant titles and/or abstracts. Subsequently, the texts of 109 articles were read in full and 71 studies were removed at this stage for failing to provide relevant information. Finally, 38 articles were selected for this review. Depression, impaired cognition, poor physical functioning, frailty, malnutrition, chronic pain, and poor self-care behavior were identified as the major diabetes-associated complications that were associated with poor glycemic control in elderly diabetic patients. Conclusions: This paper proposes that diabetes-associated complications are interrelated, and that impaired glycemic control aggravates diabetes complications; as a result, patient’s self-care abilities are compromised. A schema is generated to reflect a synthesis of the literature found through the systematic review process. This not only affects patients’ therapeutic goals, but may also hamper their health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and financial status.

1. Introduction

Diabetes is a leading cause of multiple morbidities in the elderly population, which reduces their quality of life and life expectancy. With an estimated global prevalence of 9% among adults, diabetes is expected to be the seventh preeminent cause of death by 2030 [1]. The elderly are the major victims of diabetes specifically, type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Around 30% of people in the world aged between 65 and 85 years are afflicted by T2DM; including 11.2 million Americans [2]. Similarly, the high prevalence of the disease is found among older people (70 to 79 years) living in Europe, North America and Australia [3].

The elderly are prone to various physical and mental problems due to the natural aging process, and multiple ailments associated with diabetes make the aging process even more difficult and cumbersome [4]. Depression, impaired cognition, poor physical functioning (PF), frailty, malnutrition, chronic pain, and poor self-care behaviors are the major issues associated with diabetes in the elderly [5,6,7,8]. These diabetes-associated complications (DAC) may directly affect a patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL), posing severe economic burden on the patient and society at large. It is a grim reality that despite having strong negative associations with clinical outcomes and patient’s HRQoL, DAC are overlooked by healthcare professionals when managing patients with T2DM. Clinicians appear to focus more on providing conventional treatment regimens, ignoring patient’s additional needs that are related to DAC.

Recent guidelines [9] for the management of diabetes in the elderly, provided by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), have stressed that thorough patient examination is required in-order to evaluate the presence of ailments considered to be DAC. It has been further emphasized that, in addition to providing conventional clinical care to elderly diabetic patients, these DAC should be adequately managed to improve patients’ overall health [9]. The purpose of this systematic literature review is to describe the association between DAC and glycemic control among elderly patients with diabetes and highlight the implications for patient health outcomes. Based on the available literature, a vicious cycle describing the relationship between DAC and glycemic control is proposed, and healthcare professionals are urged to optimize the management of elderly with diabetes the consideration of this cycle.

2. Methods

We systematically identified studies related to diabetes and DAC, published in the scientific literature during the period from 1 January 2000 to 22 September 2018. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies are outlined in Table 1. We followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) guidelines [10] in the preparation of this review. We have developed a protocol of methods, which can be assessed at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016030172.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.1. Search Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using Google Scholar, Medline, PubMed, Scopus, SpringerLink, and ScienceDirect databases. “Diabetes”, “Diabetes mellitus”, “Type 1 diabetes mellitus”, “Type 2 diabetes mellitus”, “Glycemic control”, “Depression”, “Cognition”, “Frailty”, “Malnutrition”, “Physical functioning”, “Pain”, “Self-care”, and “Healthcare professionals” were used as keywords in diverse combinations with Boolean and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) searches to identify all relevant studies.

Further publications were identified by manual searching of the references of related papers and review articles. Various journals in the diabetes and endocrinology domain were searched to identify further relevant articles.

2.2. Data Extraction (Selection and Coding)

A data extraction form was developed. The items on the data extraction form were finalized after discussion amongst members of the research team. The extracted data included the first author’s name, year of data (the midpoint of the study’s time period), study design, study setting, data collection method, characteristics of the patients (sample size and age), and major outcomes.

Retrieved articles were imported into Endnote X7 to remove duplicates, and they were included or excluded according to the predefined criteria. QS and MA independently assessed the titles and abstracts to select the studies. After preliminary screening, a full-text assessment was made to determine the final inclusion of articles for this review. Disagreement amongst the research team regarding the eligibility of any study was resolved through discussion and mutual agreement in the research team meetings. All authors agreed with the final studies selected for the review. Two independent reviewers checked all studies to verify the validity of the screening procedure.

2.3. Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

Two independent reviewers evaluated the data. The data were analyzed based on the quality of the data [11]. Any disagreements raised among the reviewers were resolved through discussion in the research team meeting.

2.4. Strategy for Data Synthesis

A systematic review was undertaken to ensure that synthesis produced was sourced from the maximum possible complete collection of relevant literature.

3. Results

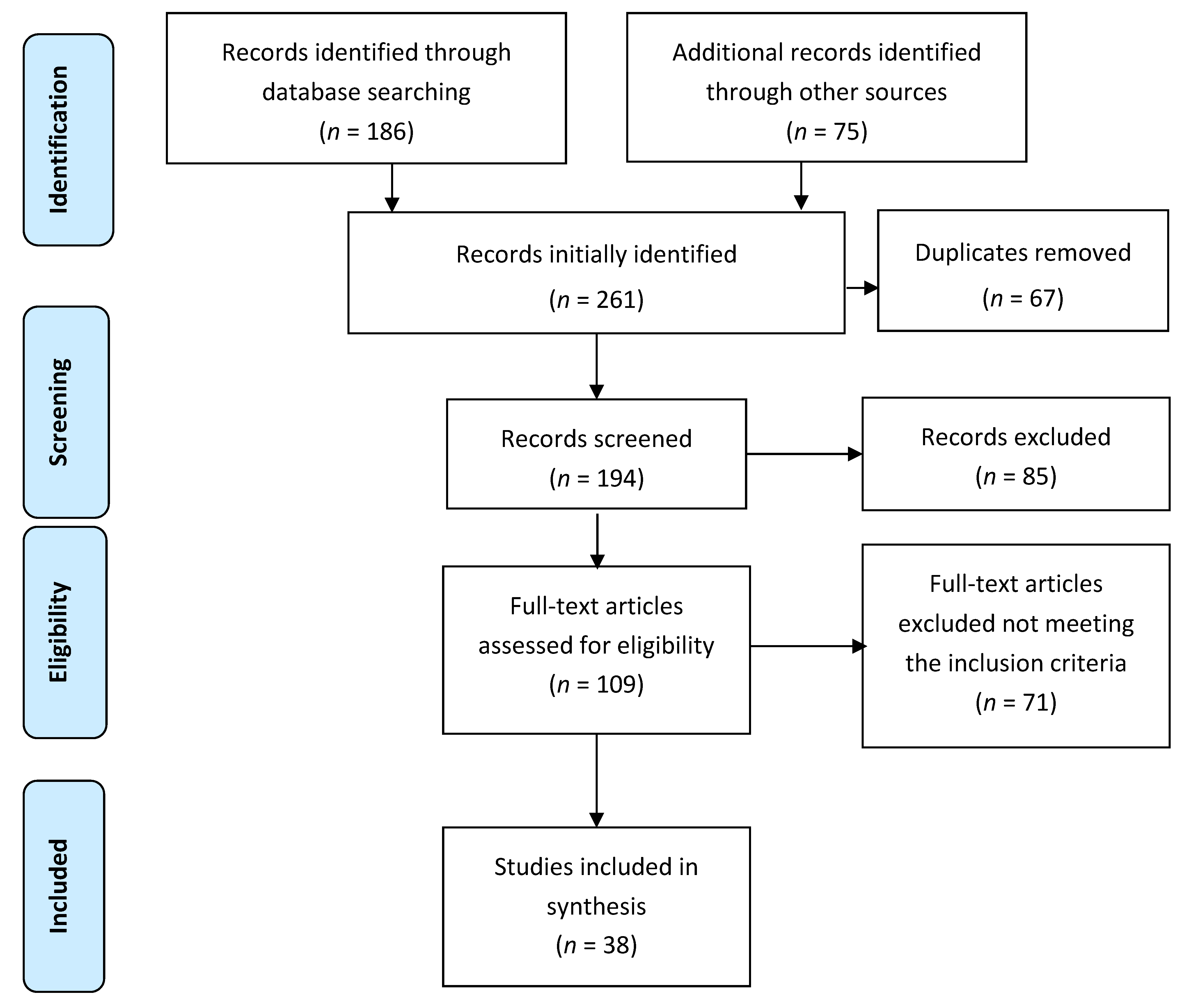

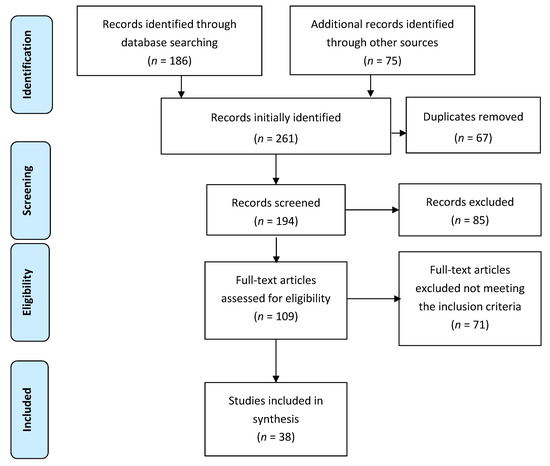

Initially, 261 studies were retrieved. Out of these, 67 were duplicates, and therefore they were excluded. From the 194 remaining articles, 85 were removed based as irrelevant titles and/or abstracts. Subsequently, the texts of 109 articles were read in full, and 71 studies were removed at this stage for failing to provide relevant information. Finally, 38 articles were selected for this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram explaining the assortment of studies/reports (2009 PRISMA flow diagram).

3.1. Characteristics of Selected Studies

The major characteristics of the 38 studies meeting the criteria for review are described in Table 2. Nineteen studies were conducted in the United States (US) [6,8,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] four in the United Kingdom (UK) [29,30,31,32], three in China [7,33,34], three in Canada [35,36,37], two in Turkey [38,39], and one in each of the Netherlands [40], Switzerland [41], Taiwan [42], Mauritius [43], Malaysia [44], Finland [45], and Pakistan [46]. Sixteen studies utilized cross-sectional [7,8,13,23,24,26,32,33,34,37,38,39,43,44,45,46] study designs, three were case-control studies [29,30,31] and 15 were longitudinal or prospective studies [6,14,15,16,17,20,22,25,27,28,35,36,40,41,42]. The remaining studies adopted mixed study designs (cross-sectional and longitudinal) [12,18,19,20,21]. There was significant variation in the sample size of the included studies, ranging from 60 [13] to 9249 participants [25]. In one case-control study, only 35 cases and 35 controls were included [29]. Only one study specifically dealt with both type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and T2DM patients [8]. Fourteen studies were related specifically to T2DM [6,21,23,28,32,33,34,36,37,39,42,43,44,46]. Only one study described the association between hyperglycemia and cognitive decline [14]. The remainder of the studies did not specify the type of diabetes. In most of the studies, all of the participants were elderly people with diabetes. In a few studies however, the participants were aged greater than 18 years, but included elderly patients (>60 years) as a sub-group. Therefore, the mean age was utilized for the analysis of these studies [8,21,23,28,32,36,39,43,44].

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

3.2. Study Evaluation Criteria

The studies were evaluated using a standard quality testing protocol developed by Kamet et al. [11]. The studies included in the review were tested and scored on the basis of 14 items (each item with a maximum score of 2). Three types of scores may be assigned to each item. The item was scored as 2 if the standard criteria were met, and 1 or 0 if the quality criteria were either partially met or not met at all. If a specific item did not match the nature of the study, it was not scored, and the item(s) were excluded from the summary scores. The percentage of scores for each study was calculated which indicated the quality of the study in numerical form. The quality scores of the majority of studies ranged between 80% and 100%, and nine studies had a maximum score of 100% [7,12,24,25,27,32,34,36,43]. Four studies scored between 70% and 80% [23,28,29,39], and one study scored below 70%, but it was above the inclusion criteria requirement of 66% [41]. Detailed quality scoring of the studies is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quality evaluation of the included studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interrelationship between Diabetes-Associated Complications and Clinical Outcomes

4.1.1. Depression

Diabetes directly affects mood levels, and depression is the basic clinical manifestation of significantly altered mood. Diabetes-related hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia are the primary causes of depression in elderly diabetic patients [8,46]. Studies have illustrated that there is a high prevalence of depression among elderly diabetic patients [12,27]. Depressed diabetic patients are more prone to other health-related problems, for instance: malnutrition, poor cognition, disability, and tendency for falls [4]. Similarly, diabetic patients can demonstrate low self-esteem as well as motivational problems for achieving good glycemic control. Consequently, they show poor adherence to therapy [5,6,8]. Studies have also revealed that depressed elderly patients show minimum interest in self-care behavior [23,47] and thus, their glycemic targets remain hard to achieve [38]. Supportive behavior of healthcare professionals and family members can play a vital role in tackling depression in elderly diabetic patients. Prescribing antidepressants and efficient management of glycemic levels can also help to ameliorate depression in these patients.

4.1.2. Impaired Cognition

Cognitive decline is a component of the normal aging process, but diabetes accelerates cognitive decline in the elderly [14,16]. This is due to a reduction of extracellular glucose levels in the hippocampus, which limits activity in memory processing [5]. Studies have supported the fact that the risk of vascular dementia (1.3–3.4 folds) and Alzheimer’s disease increases with diabetes [2,4]. Prolonged and intensive insulin therapy in elderly diabetes patients has been shown to increase the risk of hypoglycemia, which has a direct association with impaired cognitive function [15]. Compromised cognition further aggravates hypoglycemia by making the patient less aware of hypoglycemic symptoms [15]. A forgetful patient also becomes unable to recognize the importance of glycemic control and self-management of their diabetes. The result is that patients suffer from poor glycemic condition which continues to afflict them as the disease progresses [13,31].

A timely diagnosis and prescribing medicines which decrease the risk of developing cerebrovascular anomalies may help prevent the expected cognitive dysfunction over time in these patients. Moreover, improving the glycemic control with pharmacotherapy may also help avert the transformation from mild cognitive decline to severe dementia in this cohort [48,49]. Healthcare professionals need to devise ways to increase concordance with prescribed medication regimens. Patients’ families and caregivers can also play a major role in supporting the diabetic patient to be more adherent of their treatment regimen, and thereby achieving positive disease outcomes.

4.2. Poor Physical Functioning

Low levels of physical functioning (LPF) and mobility are associated with the aging process because of reduced bone strength, muscle tone, and elasticity [50]. An association between LPF and diabetes has been established [7,22]. Functional decline is seen in most elderly people with diabetes who have elevated HbA1c levels [19]. Such patients show impaired activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) [7]. Poor PF may reduce self-care in patients which can adversely affect the self-management of diabetes and may result in poorer health outcomes [4,22]. Providing physiotherapy and functional aids to patients can improve their self-management by enabling them to adhere to a healthy diet plan, regular blood glucose monitoring, exercising, and foot care with ongoing monitoring [33].

4.2.1. Frailty

Hypoglycemia-induced falls are very common in elderly diabetic patients [18]. Studies have shown that the elderly diabetic patient has a greater risk of falling than any other group of older adults [17,25]. Correlation between frailty and glycemic control has been shown in a study where 77% of patients with HbA1c levels ≤7 had a fall [18]. This reveals that poor glycemic control not only increases the chances of falls in frail diabetic patients but also in non-frail elderly diabetic patients [40]. Frailty in diabetes patients is also associated with reduced ADL. Moreover, impaired cognition and depression that are associated with poor glycemic control also contribute to frailty in these patients [47]. Similarly, a direct association between frailty, poor self-efficacy, and inadequate self-care has also been established in elderly diabetes patients [51]. These associations can further aggravate the disease, and the patients suffer in terms of morbidity and mortality. Improving self-care activities and managing hypoglycemia can prevent the probability of falls occurring in these patients [35]. These patients must be counseled about keeping immediate-acting sugar substitutes on-hand in order to treat hypoglycemia in an emergency situation.

4.2.2. Pain

The prevalence of pain is high in elderly diabetic patients [24]. Diabetes is a major determinant of axonal and sensory neuropathy, which is expected to develop in half of diabetic patients who have suffered from the disease for two decades or more [26]. Neuropathy causes intense pain in some patients in the peripheral areas of the body [52,53]. A study has revealed a 26.4% prevalence of painful diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy, affecting their quality of life in many ways [32]. Another study has shown the significant impact of pain associated with diabetes-related neuropathy, affecting patients’ physical and mental wellbeing [26]. Consistent hyperglycemia associated with diabetes is the major reason for the development of neuropathy, which has been evidenced by studies that have shown that hyperglycemia and increased levels of HbA1c are observed in patients with neuropathy [18,26]. Additionally, diabetic patients also feel pain due to skin and soft tissue infections [54]. Pain reduces PF and self-care activities [55], such that patients who feel persistent pain are unable to perform much needed tasks, for example, glucose monitoring or following a diet plan. Prescribing analgesics and educating patients that they need to keep blood glucose levels within the normal range can be beneficial in preventing development of painful neuropathy and skin infections [52]. Adopting self-care activities relating to foot care is also important in this regard.

4.3. Malnutrition

Malnutrition is another significant and debilitating issue that elderly people are faced with. About 5–10% of independently living and 30–60% of hospitalized elderly patients are malnourished [38]. Malnutrition diminishes the health and well-being of diabetic patients, and affects their PF as well. The association between diabetes and the high prevalence of malnutrition in elderly diabetes patients is well established [29,41]. In a study it was found that nearly one quarter (23.7%) of diabetic patients were malnourished, despite having elevated plasma glucose levels, probably because of being in a hypermetabolic state [38]. Besides, protein catabolism and weight loss seen in elderly patients with diabetes is another reason for being malnourished. Depression and poor IADL also result in malnutrition in a way that depressed patients lack appetite, which consequently leads to poor nutritional status [29]. Irrespective of the reason, malnutrition is a risk factor for hypoglycemia that may further worsen physical and mental wellbeing [3], and thereby negatively affect levels of self-care. Consequently, poor self-care may lead to poor glycemic control and poor clinical outcomes [33]. A balanced diet containing optimum levels of essential nutrients is necessary for elderly diabetic patients. Healthcare practitioners can prescribe supplements and provide a balanced diet plan to help prevent malnutrition. Improving physical and mental health and self-care activities can also improve the diabetic patient’s nutritional status by assisting the patient to plan, prepare, and eat a balanced diet.

4.4. Poor Self-Care

Self-care is described as all the activities performed by a diabetic patient to adhere to a prescribed diet plan, and a drug therapy regime to achieve standard glycemic targets to effectively manage diabetes [56]. The extent to which patients undertake self-care has a direct relationship with glycemic control. Studies demonstrate that effective self-care translates into better glycemic control, leading to improved health outcomes and vice versa [23,33]. DAC also has links with self-care, as depression, impaired cognition, poor PF, frailty, malnutrition, and pain may hamper the ability to undertake self-care in diabetic patients, due to the associated physical and mental discomfort. Consequently, the patient cannot keep pace with self-management of the disease because of poor self-care, and may suffer from worse clinical outcomes [8,13,24,41]. The best way to improve self-care abilities and to achieve adequate glycemic control is through the prevention of DAC in the first place. In this regard, there is a need for the early detection and management of DAC to boost the level of self-care among elderly diabetic patients.

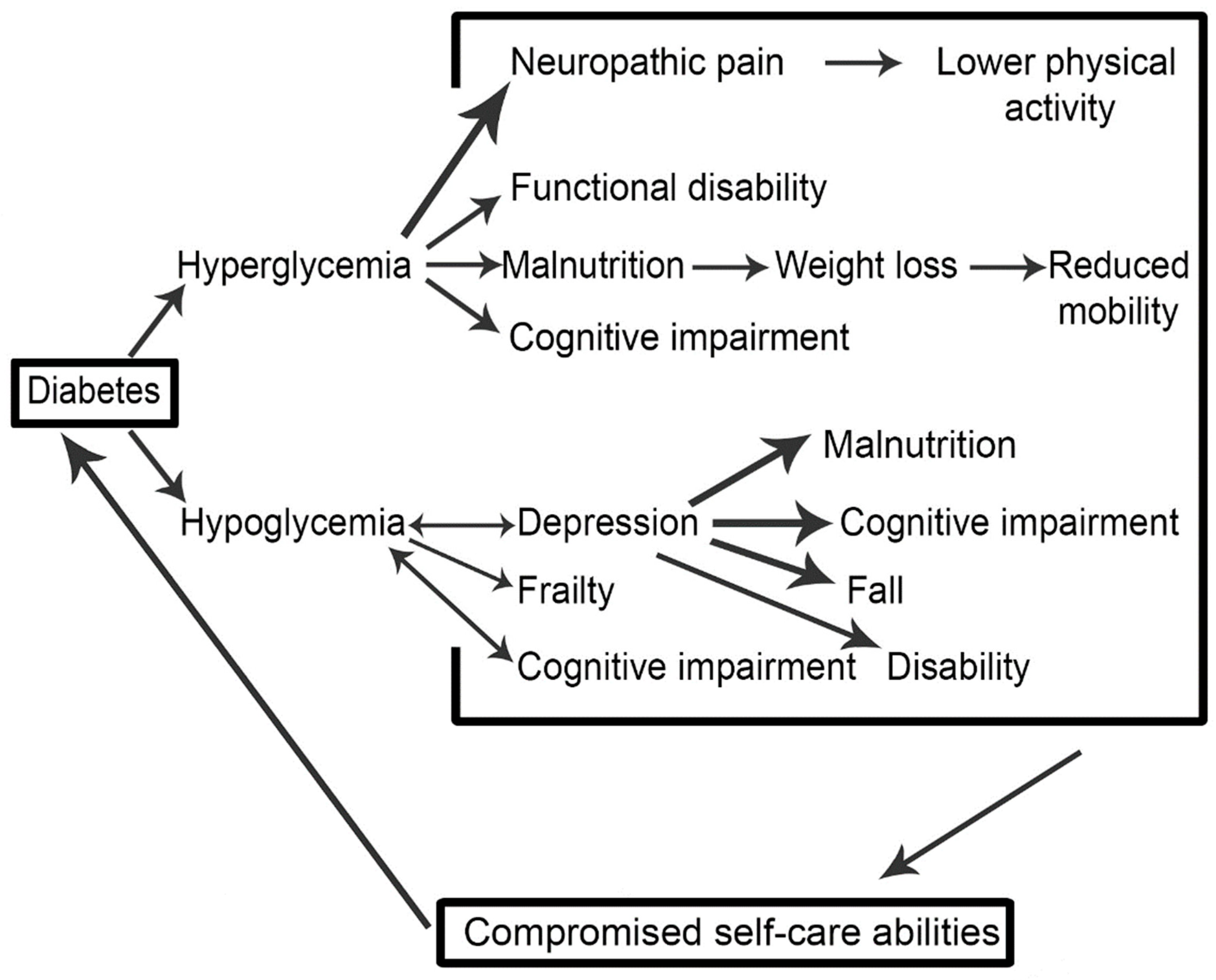

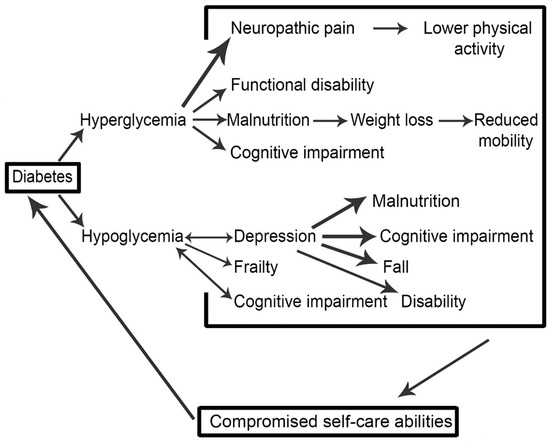

4.5. A Schema of the Vicious Cycle of Diabetes-Associated Complications (DAC) and Their Outcomes

Figure 2 is a schematic interpretation of our synthesis of the literature associated with diabetes-related complications in the older adult. The schema demonstrates in a visual form the association of DAC with glycemic control, and how these linkages are connected to self-care abilities, potentially forming a vicious cycle. Impaired glycemic control (hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia) leads to the development of DAC that again results in poor glycemic control. If it continues, such a mechanism may result in worse health outcomes, and subsequent high societal burden. The aim of developing this schema is to pictorially represent the complexity associated with diabetes management, and to draw the literature together around diabetes-associated complications (DAC) whilst thinking about how the relationships between the various complications might manifest. Of course, outcomes for patients and wider society are ultimately thought about and implicated.

Figure 2.

A vicious cycle explaining the relationship between of diabetes associated complications and glycemic control.

Diabetes complications (microvascular and macrovascular) are not considered in the proposed vicious cycle, despite the fact that these complications can also affect glycemic control. It is suggested that future studies should attempt to address this complex paradigm. Another limitation of this systematic review is that only the elderly group of diabetic patients was considered. We included this subgroup of diabetes patients because this is the most vulnerable group for the development of DAC, as compared to other age groups. The association between DAC and glycemic control needs to be better understood through modelling the literature within this context. Future studies should also investigate this relationship empirically, based on patient characteristics such as gender, education level etc.

5. Conclusions

A thorough review of literature has revealed that DACs that are associated with diabetes is a complex area, and in the elderly the literature can be formulated into a schema demonstrating its interconnectedness. Impaired glycemic control aggravates DAC, and as a result, patients’ self-care abilities are compromised. This not only affects patients’ therapeutic goals, but also their HRQoL.

Improved HRQoL and increased life expectancy are major health intentions for elderly diabetic patients, which can be achieved by setting glycemic targets and maintaining good glycemic control. This calls for a collaborative effort by healthcare professionals (physicians, nurses, and pharmacists), patients’ families and caregivers, and the patients themselves. All efforts performed by the caregivers and the healthcare professionals may fail if patients show a reluctance to perform self-care activities to manage the disease. Healthcare professionals should consider the management of DAC while making treatment decisions, rather than simply following conventional drug therapy strategies. Prioritizing DAC can not only help to break the vicious cycle, but it can also help to improve patients’ HRQoL.

Author Contributions

Q.S. and M.A. conceived the idea. Q.S. was involved in original draft preparation. M.A., S.S. and Z.u.D.B critically revised and amended the draft. Final version of manuscript was approved by all authors.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Diabetes (Key Facts). Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/ (accessed on 30 June 2016).

- Samaras, K.; Sachdev, P.S. Diabetes and the elderly brain: Sweet memories? Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 3, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdel Marchasson, I.; Doucet, J.; Bauduceau, B.; Berrut, G.; Blickle, J.F.; Brocker, P.; Constans, T.; Fagot Campagna, A.; Kaloustian, E.; Lassmann Vague, V.; et al. Key priorities in managing glucose control in older people with diabetes. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, A.; Ito, H. Diabetes mellitus and geriatric syndromes. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2009, 9, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, N.; Gagnon, M.; Messier, C. The relationship between impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes, and cognitive function. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2004, 26, 1044–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, S.A.; Markides, K.S.; Ray, L.A. Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 2822–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, K.L.; Chi, I. Functional disability related to diabetes mellitus in older Hong Kong Chinese adults. Gerontology 2005, 51, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciechanowski, P.S.; Katon, W.J.; Russo, J.E.; Hirsch, I.B. The relationship of depressive symptoms to symptom reporting, self-care and glucose control in diabetes. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2003, 25, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. International Diabetes Federation Managing Older People with Type 2 Diabetes Global Guidelines; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmet, L.M.; Lee, R.C.; Cook, L.S. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/supplementary/1471-2393-14-52-s2.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2016).

- Blazer, D.G.; Moody-Ayers, S.; Craft-Morgan, J.; Burchett, B. Depression in diabetes and obesity: Racial/ethnic/gender issues in older adults. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, M.; Grande, L.; Hayes, M.; Ayres, D.; Suhl, E.; Capelson, R.; Lin, S.; Milberg, W.; Weinger, K. Cognitive dysfunction is associated with poor diabetes control in older adults. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1794–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaffe, K.; Haan, M.; Blackwell, T.; Cherkasova, E.; Whitmer, R.A.; West, N. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline in elderly Latinos: Findings from the Sacramento Area Latino Study of Aging study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaffe, K.; Falvey, C.M.; Hamilton, N.; Harris, T.B.; Simonsick, E.M.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; Shorr, R.I.; Metti, A.; Schwartz, A.V.; Health, A.B.C.S. Association between hypoglycemia and dementia in a biracial cohort of older adults with diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaffe, K.; Falvey, C.; Hamilton, N.; Schwartz, A.V.; Simonsick, E.M.; Satterfield, S.; Cauley, J.A.; Rosano, C.; Launer, L.J.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; et al. Diabetes, glucose control, and 9-year cognitive decline among older adults without dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, M.S.; Burcham, J.; Cheng, H. Diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased risk of falls in elderly residents of a long-rerm care facility. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2005, 60, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.M.; Dufraux, K.; Cook, P.F. The relationship between glycemic control and falls in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 2041–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyani, R.R.; Saudek, C.D.; Brancati, F.L.; Selvin, E. Association of diabetes, comorbidities, and A1C with functional disability in older adults: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999–2006. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.K.; Jones, R.N.; Milberg, W.P.; Tennstedt, S.; Talbot, L.; Morris, J.N.; Lipsitz, L.A. Effect of blood pressure and diabetes mellitus on cognitive and physical functions in older adults: A longitudinal analysis of the advanced cognitive training for independent and vital elderly cohort. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 1154–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, E.H.; Katon, W.; Von Korff, M.; Rutter, C.; Simon, G.E.; Oliver, M.; Ciechanowski, P.; Ludman, E.J.; Bush, T.; Young, B. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2154–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhamoon, M.S.; Moon, Y.P.; Paik, M.C.; Sacco, R.L.; Elkind, M.S. Diabetes predicts long-term disability in an elderly urban cohort: The Northern Manhattan Study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egede, L.E.; Osborn, C.Y. Role of motivation in the relationship between depression, self-care, and glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krein, S.L.; Heisler, M.; Piette, J.D.; Makki, F.; Kerr, E.A. The effect of chronic pain on diabetes patients’ self-management. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.V.; Hillier, T.A.; Sellmeyer, D.E.; Resnick, H.E.; Gregg, E.; Ensrud, K.E.; Schreiner, P.J.; Margolis, K.L.; Cauley, J.A.; Nevitt, M.C.; et al. Older women with diabetes have a higher risk of falls: A prospective study. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1749–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galer, B.S.; Gianas, A.; Jensen, M.P. Painful diabetic polyneuropathy: Epidemiology, pain description, and quality of life. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2000, 47, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraldi, C.; Volpato, S.; Penninx, B.W.; Yaffe, K.; Simonsick, E.M.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; Cesari, M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Perry, S.; Ayonayon, H.N.; et al. Diabetes mellitus, glycemic control, and incident depressive symptoms among 70- to 79-year-old persons: The health, aging, and body composition study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marden, J.R.; Mayeda, E.R.; Tchetgen, E.J.T.; Kawachi, I.; Glymour, M.M. High Hemoglobin A1c and Diabetes Predict Memory Decline in the Health and Retirement Study. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2017, 31, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, P.; Sinclair, A. Evaluation of nutritional status and its relationship with functional status in older citizens with diabetes mellitus using the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) tool. A preliminary investigation. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2002, 6, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Conroy, S.P.; Bayer, A.J. Impact of diabetes on physical function in older people. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Girling, A.J.; Bayer, A.J. Cognitive dysfunction in older subjects with diabetes mellitus: Impact on diabetes self-management and use of care services. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2000, 50, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Brophy, S.; Williams, R.; Taylor, A. The prevalence, severity, and impact of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1518–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Wang, J.; Zheng, P.; Haardorfer, R.; Kegler, M.C.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, H. Effects of self-care, self-efficacy, social support on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, A.C.; Tse, G.; Cheng, H.L.; Lau, E.S.; Luk, A.; Osaki, R.; So, T.T.; Wong, R.Y.; Tsoh, J.; Chow, E. Depressive symptoms and glycemic control in Hong Kong Chinese elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, R.E.; Andrew, M.K.; Fallah, N.; Rockwood, K. Comparison of the prognostic importance of diagnosed diabetes, co-morbidity and frailty in older people. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, D.M.; Al Sayah, F.; Vallance, J.K.; Johnson, S.T.; Johnson, J.A. Association between physical activity and health-related quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 2017, 41, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneilly, G.S.; Berard, L.D.; Cheng, A.Y.; Lin, P.J.; MacCallum, L.; Tsuyuki, R.T.; Yale, J.-F.; Nasseri, N.; Richard, J.-F.; Goldin, L. Insights into the current management of older adults with type 2 diabetes in the Ontario primary care setting. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulger, Z.; Halil, M.; Kalan, I.; Yavuz, B.B.; Cankurtaran, M.; Gungor, E.; Ariogul, S. Comprehensive assessment of malnutrition risk and related factors in a large group of community-dwelling older adults. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 29, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, Z.G.; Uzunlulu, M.; Caklili, O.T.; Mutlu, H.H.; Oguz, A. Malnutrition rate among hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Prog. Nutr. 2018, 20, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pijpers, E.; Ferreira, I.; de Jongh, R.T.; Deeg, D.J.; Lips, P.; Stehouwer, C.D.; Nieuwenhuijzen Kruseman, A.C. Older individuals with diabetes have an increased risk of recurrent falls: Analysis of potential mediating factors: The Longitudinal Ageing Study Amsterdam. Age Ageing 2012, 41, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vischer, U.M.; Perrenoud, L.; Genet, C.; Ardigo, S.; Registe-Rameau, Y.; Herrmann, F.R. The high prevalence of malnutrition in elderly diabetic patients: Implications for anti-diabetic drug treatments. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, Y.-W.; Lin, C.-H.; Lee, I.-T.; Chang, M.-H. Variability of fasting plasma glucose and the risk of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2018, 44, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabesh, M.; Shaw, J.E.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Söderberg, S.; Koye, D.N.; Kowlessur, S.; Timol, M.; Joonas, N.; Sorefan, A.; Gayan, P. Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and disability: What is the contribution of diabetes risk factors and diabetes complications? J. Diabetes 2018, 10, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharek, Z.; Ramli, A.S.; Whitford, D.L.; Ismail, Z.; Zulkifli, M.M.; Sharoni, S.K.A.; Shafie, A.A.; Jayaraman, T. Relationship between self-efficacy, self-care behaviour and glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Malaysian primary care setting. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aro, A.-K.; Karjalainen, M.; Tiihonen, M.; Kautiainen, H.; Saltevo, J.; Haanpää, M.; Mäntyselkä, P. Glycemic control and health-related quality of life among older home-dwelling primary care patients with diabetes. Prim. Care Diabetes 2017, 11, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuberi, S.I.; Syed, E.U.; Bhatti, J.A. Association of depression with treatment outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A cross-sectional study from Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinger, K.; Beverly, E.A.; Smaldone, A. Diabetes self-care and the older adult. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2014, 36, 1272–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquier, F.; Boulogne, A.; Leys, D.; Fontaine, P. Diabetes mellitus and dementia. Diabetes Metab. 2006, 32, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.H.; Haan, M.N.; Liang, J.; Ghosh, D.; Gonzalez, H.M.; Herman, W.H. Impact of antidiabetic medications on physical and cognitive functioning of older Mexican Americans with diabetes mellitus: A population-based cohort study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2003, 13, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodpaster, B.H.; Park, S.W.; Harris, T.B.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Nevitt, M.; Schwartz, A.V.; Simonsick, E.M.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Visser, M.; Newman, A.B. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: The health, aging and body composition study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006, 61, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, S.; Zammitt, N.N.; Frier, B.M. Optimal glycaemic control in elderly people with type 2 diabetes: What does the evidence say? Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchettini, P.; Lacerenza, M.; Mauri, E.; Marangoni, C. Painful peripheral neuropathies. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2006, 4, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmader, K.E. Epidemiology and impact on quality of life of postherpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy. Clin. J. Pain 2002, 18, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Koirala, J.; Khardori, R.; Khardori, N. Infections in diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 21, 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.V.; Guralnik, J.M.; Dansie, E.J.; Turk, D.C. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: Findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. Pain 2013, 154, 2649–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinger, K.; Butler, H.A.; Welch, G.W.; La Greca, A.M. Measuring diabetes self-care: A psychometric analysis of the Self-Care Inventory-Revised with adults. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).