The MIR 2018 Exam: Psychometric Study and Comparison with the Previous Nine Years

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Examination Under Study

2.2. Database

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Reliability

2.3.2. Difficulty Index

2.3.3. Difficulty Index with Correction of Random Effects

2.3.4. Discrimination Index

2.3.5. Point Biserial Correlation Index

2.3.6. The Two Parameter Model of IRT

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Exam Questions

3.2. Analysis of Exam Questions Grouped by Subject

3.3. Analysis of the Exam Questions Grouped by Logs or Blocks

3.4. Analysis by Question Type

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto 2015/1978, de 15 de Julio Por el Que se Regula la Obtención de Títulos de Especialidades Médicas; BOE Number 206; Ministry of the Presidency, Relations with the Courts and Equality: Madrid, Spain, 1978; pp. 20172–20174.

- Curbelo, J.; Romeo, J.M.; Galván-Román, J.M.; Vega-Villar, J.; Martinez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Jiménez-Fonseca, P.; Villacampa, T.; Sánchez-Lasheras, F.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Baladrón, J. The popularity of neurology in Spain: An analysis of specialty selection. Neurología 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curbelo, J.; Romeo, J.M.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Sánchez Lasheras, F.; Baladrón, J. Endocrinology and nutrition: Evolution of the choice of specialty in the last years. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curbelo, J.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Romero, J.M.; Villacampa, T.; Sánchez-Lasheras, F.; Baladrón, J. Choice of critical care medicine: Analysis of the last 10 years. Med. Intensiva 2018, 42, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curbelo, J.; Galván-Román, J.M.; Sánchez-Lasheras, F.; Romeo, J.M.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Villacampa, T.; Baladrón, J. Aparato Digestivo: Evolución de la elección de la especialidad en los últimos años. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2018, 109, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murias Quintana, E.; Sánchez Lasheras, F.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Romeo Ladrero, J.M.; Costilla García, S.M.; Cadenas Rodríguez, M.; Baladrón Romero, J.B. Choice of the specialty of diagnostic radiology by results of the competitive examination to assign residency positions from 2006 to 2015. Radiología 2017, 59, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñiz, J. Teoría Clásica de Los Test, 2nd ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, F.M. Applications of Item Response Theory to Practical Testing Problems; Erlbaum: Hillside, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Baladrón, J.; Curbelo, J.; Sánchez-Lasheras, F.; Romeo-Ladrero, J.M.; Villacampa, T.; Fernández-Somoano, A. El examen al examen MIR 2015: Aproximación a la validez estructural a través de la teoría clásica de los tests. FEM: Revista de la Fundación Educación Médica 2016, 19, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruebas Selectivas Para el Acceso a Plazas de Formación de Médicos Especialistas (1982–1992); Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo: Madrid, Spain, 1993.

- Baladrón, J.; Sánchez-Lasheras, F.; Villacampa, T.; Romeo-Ladrero, J.M.; Jiménez-Fonseca, P.; Curbelo, J.; Fernández-Somoano, A. El examen MIR 2015 desde el punto de vista de la teoría de respuesta al ítem. FEM: Revista de la Fundación Educación Médica 2017, 20, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Baladrón, J.; Sánchez-Lasheras, F.; Romeo-Ladrero, J.M.; Curbelo, J.; Villacampa-Menéndez, P.; Jiménez-Fonseca, P. Evolución de los parámetros dificultad y discriminación en el ejercicio de examen MIR. Análisis de las convocatorias de 2009 a 2017. FEM: Revista de la Fundación Educación Médica 2018, 21, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez Galán, C.; Sánchez Lasheras, F.; de Cos Juez, F.J.; Bernardo Sánchez, A. Missing data imputation of questionnaires by means of genetic algorithms with different fitness functions. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2017, 311, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baladrón Romero, J.; Sánchez Lasheras, F.; Villacampa Castro, T.; Romeo Ladrero, J.M.; Jiménez Fonseca, P.; Curbelo, J.; Fernández Somoano, A. Propuesta metodológica para la detección de preguntas susceptibles de anulación en la prueba MIR. Aplicación a las convocatorias 2010 a 2015. FEM: Revista de la Fundación Educación Médica 2017, 20, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Díez, M.C.; Alegre, M.; Díez, N.; Arbea, L.; Ferrer, M. Technical flaws in multiple-choice questions in the access exam to specialties (examen MIR). BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 3, 16–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonillo, A. Pruebas de acceso a la formación sanitaria especializada para médicos y otros profesionales sanitarios en España: Examinando el examen y los examinados. Gac. Sanit. 2012, 26, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Difficulty Index | Difficulty Index with Random Effects Correction | Discrimination Index | Correlation Index Point Biserial | Discrimination Index IRT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | Categories | Values | Categories | Values | Categories | Values | Categories | Values | Categories |

| >0.8 | Easy | >0.8 | Very easy | >0.34 | Excellent | >0.39 | Excellent | >1 | Excellent |

| >0.6 to 0.8 | Acceptable | >0.66 to 0.80 | Easy | >0.24 to 0.34 | Good | >0.30 to 0.39 | Good | >0.70 to 1 | Good |

| >0.5 to 0.6 | Excellent | >0.33 to 0.66 | Excellent | >0.14 to 0.24 | Revisable | >0.20 to 0.30 | Regular | >0.40 to 0.70 | Regular |

| >0.3 to 0.5 | Acceptable | >0 to 0.33 | Difficult | 0 to 0.14 | Bad | 0–0.20 | Poor | 0–0.40 | Poor |

| 0–0.3 | Difficult | –0.33 to 0 | Very difficult | <0 | Very bad | <0 | Lousy | <0 | Lousy |

| Block | Subject | Number of Questions | Difficulty Index | Difficulty Index with Random Effects Correction | Discrimination Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systems | Digestive | 16 | 0.679 (0.276) | 0.577 (0.366) | 0.209 (0.098) |

| Cardiology | 15 | 0.732 (0.155) | 0.648 (0.206) | 0.170 (0.127) | |

| Infectious Diseases | 14 | 0.514 (0.294) | 0.360 (0.394) | 0.238 (0.118) | |

| Nephrology | 13 | 0.671 (0.226) | 0.566 (0.298) | 0.309 (0.008) | |

| Endocrinology | 12 | 0.643 (0.253) | 0.535 (0.326) | 0.229 (0.107) | |

| Pneumology | 11 | 0.706 (0.182) | 0.614 (0.239) | 0.289 (0.084) | |

| Neurology | 10 | 0.722 (0.143) | 0.641 (0.191) | 0.320 (0.129) | |

| Haematology | 10 | 0.652 (0.209) | 0.545 (0.268) | 0.255 (0.004) | |

| Rheumatology | 6 | 0.656 (0.168) | 0.545 (0.225) | 0.398 (0.003) | |

| Basic | Genetics | 6 | 0.816 (0.072) | 0.766 (0.088) | 0.169 (0.016) |

| Immunology | 5 | 0.528 (0.177) | 0.388 (0.225) | 0.182 (0.001) | |

| Anatomy | 5 | 0.482 (0.279) | 0.319 (0.373) | 0.021 (0.120) | |

| Pharmacology | 5 | 0.529 (0.173) | 0.380 (0.232) | 0.157 (0.003) | |

| Pathological Anatomy | 4 | 0.376 (0.204) | 0.197 (0.238) | 0.075 (0.086) | |

| Biochemistry | 1 | 0.486 | 0.369 | 0.162 | |

| Other | Preventive | 17 | 0.588 (0.235) | 0.466 (0.311) | 0.309 (0.079) |

| Gynaecology and Obstetrics | 12 | 0.613 (0.198) | 0.492 (0.265) | 0.328 (0.110) | |

| Paediatrics | 10 | 0.581 (0.271) | 0.452 (0.357) | 0.378 (0.063) | |

| Psychiatry | 7 | 0.725 (0.134) | 0.642 (0.181) | 0.409 (0.072) | |

| Traumatology | 7 | 0.628 (0.144) | 0.514 (0.192) | 0.376 (0.102) | |

| Clinical Management | 5 | 0.524 (0.321) | 0.378 (0.422) | 0.290 (0.136) | |

| Emergency | 5 | 0.602 (0.222) | 0.475 (0.295) | 0.480 (0.032) | |

| Ophthalmology | 4 | 0.751 (0.099) | 0.673 (0.130) | 0.296 (0.108) | |

| Dermatology | 4 | 0.407 (0.034) | 0.221 (0.046) | 0.130 (0.087) | |

| Physiology | 3 | 0.682 (0.067) | 0.597 (0.082) | 0.169 (0.001) | |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 3 | 0.709 (0.275) | 0.621 (0.358) | 0.229 (0.080) | |

| Oncology | 3 | 0.568 (0.134) | 0.433 (0.177) | 0.456 (0.003) | |

| Palliatives | 3 | 0.593 (0.318) | 0.461 (0.423) | 0.466 (0.006) | |

| Geriatrics | 3 | 0.348 (0.245) | 0.140 (0.333) | 0.442 (0.005) | |

| Maxilo-Facial Surgery | 2 | 0.658 (0.067) | 0.551 (0.092) | 0.269 (0.002) | |

| Plastic Surgery | 2 | 0.658 (0.084) | 0.573 (0.079) | 0.427 (0.005) | |

| Anaesthesiology | 2 | 0.844 (0.073) | 0.798 (0.095) | 0.420 (0.001) | |

| Vascular Surgery | 2 | 0.297 (0.231) | 0.075 (0.317) | 0.090 (0.066) | |

| Bioethics | 1 | 0.941 | 0.922 | 0.421 | |

| Communication Skills | 1 | 0.971 | 0.964 | 0.482 | |

| Legal Medicine | 1 | 0.667 | 0.568 | 0.481 | |

| Total | 230 | 0.629 (0.226) | 0.515 (0.297) | 0.277 (0.130) |

| Block | Subject | Number of Questions | Point Biserial Correlation | Difficulty IRT | IRT Discrimination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systems | Digestive | 16 | 0.246 (0.160) | −8.065 (23.309) | 0.629 (0.508) |

| Cardiology | 15 | 0.305 (0.130) | −1.860 (1.147) | 0.787 (0.482) | |

| Infectious Diseases | 14 | 0.249 (0.213) | −6.094 (23.097) | 0.642 (0.763) | |

| Nephrology | 13 | 0.267 (0.096) | −0.685 (3.268) | 0.655 (0.348) | |

| Endocrinology | 12 | 0.314 (0.121) | −0.959 (2.493) | 0.794 (0.357) | |

| Pneumology | 11 | 0.283 (0.132) | −3.974 (7.777) | 0.704 (0.416) | |

| Neurology | 10 | 0.311 (0.082) | −1.634 (1.233) | 0.758 (0.294) | |

| Haematology | 10 | 0.339 (0.121) | −0.739 (1.657) | 0.856 (0.459) | |

| Rheumatology | 6 | 0.281 (0.121) | −1.016 (0.945) | 0.686 (0.438) | |

| Basic | Genetics | 6 | 0.395 (0.080) | −1.892 (0.334) | 1.067 (0.374) |

| Immunology | 5 | 0.311 (0.117) | 0.194 (1.582) | 0.679 (0.321) | |

| Anatomy | 5 | 0.176 (0.078) | 1.291 (4.446) | 0.368 (0.125) | |

| Pharmacology | 5 | 0.257 (0.067) | −0.188 (1.719) | 0.539 (0.143) | |

| Pathological Anatomy | 4 | 0.145 (0.156) | 6.849 (13.448) | 0.315 (0.337) | |

| Biochemistry | 1 | 0.257 | 0.066 | 0.536 | |

| Other | Preventive | 17 | 0.271 (0.099) | −0.329 (2.449) | 0.635 (0.259) |

| Gynaecology and Obstetrics | 12 | 0.236 (0.106) | 0.83 (6.826) | 0.515 (0.273) | |

| Paediatrics | 10 | 0.239 (0.139) | 6.311 (20.638) | 0.604 (0.447) | |

| Psychiatry | 7 | 0.279 (0.119) | −1.780 (0.97) | 0.661 (0.515) | |

| Traumatology | 7 | 0.294 (0.082) | −0.930 (1.043) | 0.617 (0.221) | |

| Clinical Management | 5 | 0.258 (0.134) | 0.726 (3.661) | 0.685 (0.407) | |

| Emergency | 5 | 0.197 (0.116) | 1.264 (7.176) | 0.391 (0.257) | |

| Ophthalmology | 4 | 0.375 (0.158) | −1.677 (0.372) | 0.991 (0.599) | |

| Dermatology | 4 | 0.198 (0.073) | 1.863 (2.38) | 0.374 (0.187) | |

| Physiology | 3 | 0.255 (0.034) | −1.755 (0.853) | 0.503 (0.061) | |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 3 | 0.313 (0.123) | −1.656 (1.883) | 1.107 (0.978) | |

| Oncology | 3 | 0.385 (0.099) | −0.320 (0.696) | 0.959 (0.386) | |

| Palliatives | 3 | 0.307 (0.096) | −0.453 (2.396) | 0.733 (0.227) | |

| Geriatrics | 3 | 0.152 (0.203) | 57.036 (51.707) | 0.304 (0.505) | |

| Maxilo-Facial Surgery | 2 | 0.289 (0.051) | −1.260 (0.281) | 0.5814 (0.157) | |

| Plastic Surgery | 2 | 0.193 (0.005) | −1.936 (1.202) | 0.376 (0.035) | |

| Anaesthesiology | 2 | 0.369 (0.067) | −2.178 (0.143) | 0.997 (0.358) | |

| Vascular Surgery | 2 | 0.164 (0.162) | 11.891 (16.472) | 0.338 (0.366) | |

| Bioethics | 1 | 0.481 | −2.270 | 2.006 | |

| Communication Skills | 1 | 0.372 | −2.908 | 1.887 | |

| Legal Medicine | 1 | 0.270 | −1.482 | 0.518 | |

| Total | 230 | 0.275 (0.129) | −0.389 (13.143) | 0.677 (0.443) |

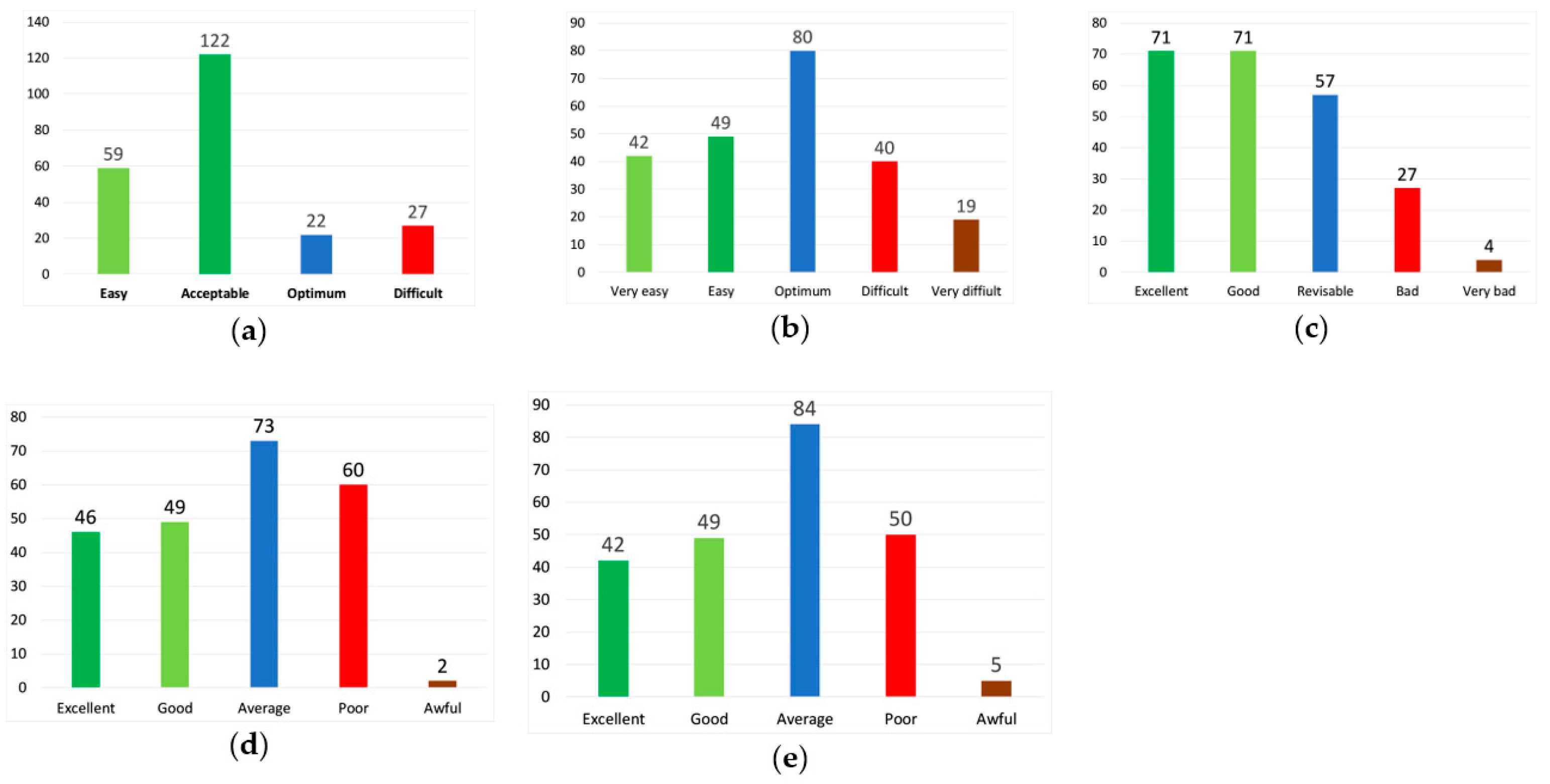

| Difficulty Index (Categories) | |||||||

| Difficulty Index | Easy | Acceptable | Optimal | Difficult | Total | ||

| Basic | 0.561 (0.227) | 3 | 16 | 4 | 3 | 26 | |

| Systems | 0.663 (0.226) | 37 | 49 | 9 | 12 | 107 | |

| Other | 0.609 (0.221) | 19 | 57 | 9 | 12 | 97 | |

| Total | 0.629 (0.226) | 59 | 122 | 22 | 27 | 230 | |

| Difficulty index with correction of random effects (categories) | |||||||

| Difficulty index with random effects correction | Very easy | Easy | Optimal | Difficult | Very difficult | Total | |

| Basic | 0.431 (0.295) | 3 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 26 |

| Systems | 0.558 (0.299) | 25 | 24 | 36 | 13 | 9 | 107 |

| Other | 0.489 (0.292) | 14 | 21 | 33 | 21 | 8 | 97 |

| Total | 0.515 (0.297) | 42 | 49 | 80 | 40 | 19 | 230 |

| Discrimination index (categories) | |||||||

| Discrimination Index | Excellent | Good | Revisable | Bad | Very bad | Total | |

| Basic | 0.126 (0.085) | 0 | 0 | 20 | 2 | 4 | 26 |

| Systems | 0.256 (0.109) | 11 | 49 | 31 | 16 | 0 | 107 |

| Other | 0.342 (0.118) | 60 | 22 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 97 |

| Total | 0.277 (0.129) | 71 | 71 | 57 | 27 | 4 | 230 |

| Point biserial correlation index (categories) | |||||||

| Point biserial correlation index | Excellent | Good | Regular | Poor | Too bad | Total | |

| Basic | 0.267 (0.129) | 5 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 26 |

| Systems | 0.286 (0.139) | 23 | 23 | 37 | 22 | 2 | 107 |

| Other | 0.267 (0.117) | 11 | 28 | 29 | 29 | 0 | 97 |

| Total | 0.275 (0.128) | 39 | 56 | 73 | 60 | 2 | 230 |

| Discrimination index IRT (categories) | |||||||

| Discrimination Index IRT | Excellent | Good | Regular | Poor | Too bad | Total | |

| Basic | 0.620 (0.377) | 27 | 18 | 42 | 15 | 5 | 107 |

| Systems | 0.719 (0.471) | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 26 |

| Other | 0.646 (0.427) | 11 | 25 | 35 | 26 | 0 | 97 |

| Total | 0.677 (0.443) | 42 | 49 | 84 | 50 | 5 | 230 |

| Difficulty index (categories) | |||||||

| Difficulty index | Easy | Acceptable | Optimal | Difficult | Total | ||

| Clinical Cases | 0.662 (0.216) | 32 | 60 | 10 | 9 | 111 | |

| Clinical cases with image | 0.561 (0.244) | 7 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 32 | |

| Negative | 0.645 (0.224) | 15 | 26 | 3 | 6 | 50 | |

| Test | 0.568 (0.221) | 5 | 21 | 4 | 7 | 37 | |

| Total | 0.629 (0.226) | 59 | 122 | 22 | 27 | 230 | |

| Difficulty index with random effects correction (categories) | |||||||

| Difficulty index with random effects correction | Very easy | Easy | Optimal | Difficult | Very difficult | Total | |

| Clinical Cases | 0.557 (0.286) | 26 | 25 | 37 | 16 | 7 | 111 |

| Clinical cases with image | 0.426 (0.323) | 4 | 5 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 32 |

| Negative | 0.535 (0.294) | 10 | 12 | 15 | 10 | 3 | 50 |

| Test | 0.437 (0.293) | 2 | 7 | 17 | 6 | 5 | 37 |

| Total | 0.515 (0.297) | 42 | 49 | 80 | 40 | 19 | 230 |

| Discrimination index (categories) | |||||||

| Discrimination Index | Excellent | Good | Revisable | Bad | Very bad | Total | |

| Clinical Cases | 0.278 (0.127) | 34 | 34 | 30 | 10 | 3 | 111 |

| Clinical cases with image | 0.225 (0.117) | 6 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 32 |

| Negative | 0.289 (0.112) | 18 | 17 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 50 |

| Test | 0.302 (0.159) | 13 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 37 |

| Total | 0.277 (0.129) | 71 | 71 | 57 | 27 | 4 | 230 |

| Point biserial correlation index (categories) | |||||||

| Point biserial correlation index | Excellent | Good | Regular | Poor | Too bad | Total | |

| Clinical Cases | 0.291 (0.131) | 24 | 33 | 28 | 24 | 2 | 111 |

| Clinical cases with image | 0.188 (0.087) | 1 | 1 | 13 | 17 | 0 | 32 |

| Negative | 0.305 (0.126) | 14 | 8 | 18 | 10 | 0 | 50 |

| Test | 0.263 (0.122) | 7 | 7 | 14 | 9 | 0 | 37 |

| Total | 0.275 (0.128) | 46 | 49 | 73 | 60 | 2 | 230 |

| Discrimination index IRT (categories) | |||||||

| Discrimination Index IRT | Excellent | Good | Regular | Poor | Too bad | Total | |

| Clinical Cases | 0.729 (0.471) | 23 | 32 | 31 | 22 | 3 | 111 |

| Clinical cases with image | 0.416 (0.243) | 1 | 1 | 15 | 14 | 1 | 32 |

| Negative | 0.783 (0.483) | 14 | 7 | 22 | 7 | 0 | 50 |

| Test | 0.599 (0.335) | 4 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 1 | 37 |

| Total | 0.677 (0.443) | 42 | 49 | 84 | 50 | 5 | 230 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baladrón, J.; Sánchez Lasheras, F.; Romeo Ladrero, J.M.; Villacampa, T.; Curbelo, J.; Jiménez Fonseca, P.; García Guerrero, A. The MIR 2018 Exam: Psychometric Study and Comparison with the Previous Nine Years. Medicina 2019, 55, 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55120751

Baladrón J, Sánchez Lasheras F, Romeo Ladrero JM, Villacampa T, Curbelo J, Jiménez Fonseca P, García Guerrero A. The MIR 2018 Exam: Psychometric Study and Comparison with the Previous Nine Years. Medicina. 2019; 55(12):751. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55120751

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaladrón, Jaime, Fernando Sánchez Lasheras, José María Romeo Ladrero, Tomás Villacampa, José Curbelo, Paula Jiménez Fonseca, and Alberto García Guerrero. 2019. "The MIR 2018 Exam: Psychometric Study and Comparison with the Previous Nine Years" Medicina 55, no. 12: 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55120751