1. Introduction

Recently, reported incidence of the common bile duct (CBD) stones varies between 8–20% in patients with gallstone disease [

1]. However, concomitant CBD stones are found in 11% to 21% of cases during cholecystectomy [

2]. Choledocholithiasis requires a complex approach for the restoration of the biliary drainage function due to the potentially life-threating biliary complications. There is a wide range of diagnostic options which are useful at the peri-operative and intra-operative stage, however, recommendations regarding the timing and method of bile duct imaging vary. MRCP is still recommended as the method of choice at the pre-operative stage [

3] followed by therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) in the case of biliary stones as a first step and surgery afterward as a second step. Despite the significant value of MRCP, there are some limitations. MRCP may be less available in high patient flow hospitals, and it has a lower diagnostic accuracy if stones in the bile duct are smaller than 5 mm, especially in the case of biliary pancreatitis. The individual restrictions such as claustrophobia and metallic implants are significant [

2].

However, ERCP is an invasive procedure and associated with a 5–10% complication rate (post-ERCP pancreatitis, bleeding, duodenal or bile duct perforation, cholecystitis, etc.). It is associated with a 0.1–1% mortality rate mainly due to papillotomy during the procedure; thereby, ERCP is more suitable for patients with a proven diagnosis and precisely selected indications [

4,

5]. On the other hand, therapeutic ERCP may be supplemented by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), which has high sensitivity and specificity rates—93% and 96%, respectively [

2].

Due to the increased use of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) which is an effective and safe alternative to ERCP, even with some advantages in comparison with the two-step approach [

6,

7], LUS has been increasingly applied as the primary imaging to screen CBD stones and it is comparable with intraoperative cholangiography (IOC). Despite the significant diagnostic accuracy of IOC (59–100% sensitivity and 93–100% specificity) [

2], it is linked to ionizing radiation, increased operative time and a lower diagnostic accuracy than LUS. However, the advantages of LUS include high quality real-time intra-operative diagnostic of choledocholithiasis, no invasiveness, short time for imaging, possibility to repeat imaging at any stage of operation and no ionizing radiation. The aim of the study was an assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of LUS in detecting choledocholithiasis and comparison with pre-operative MRCP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

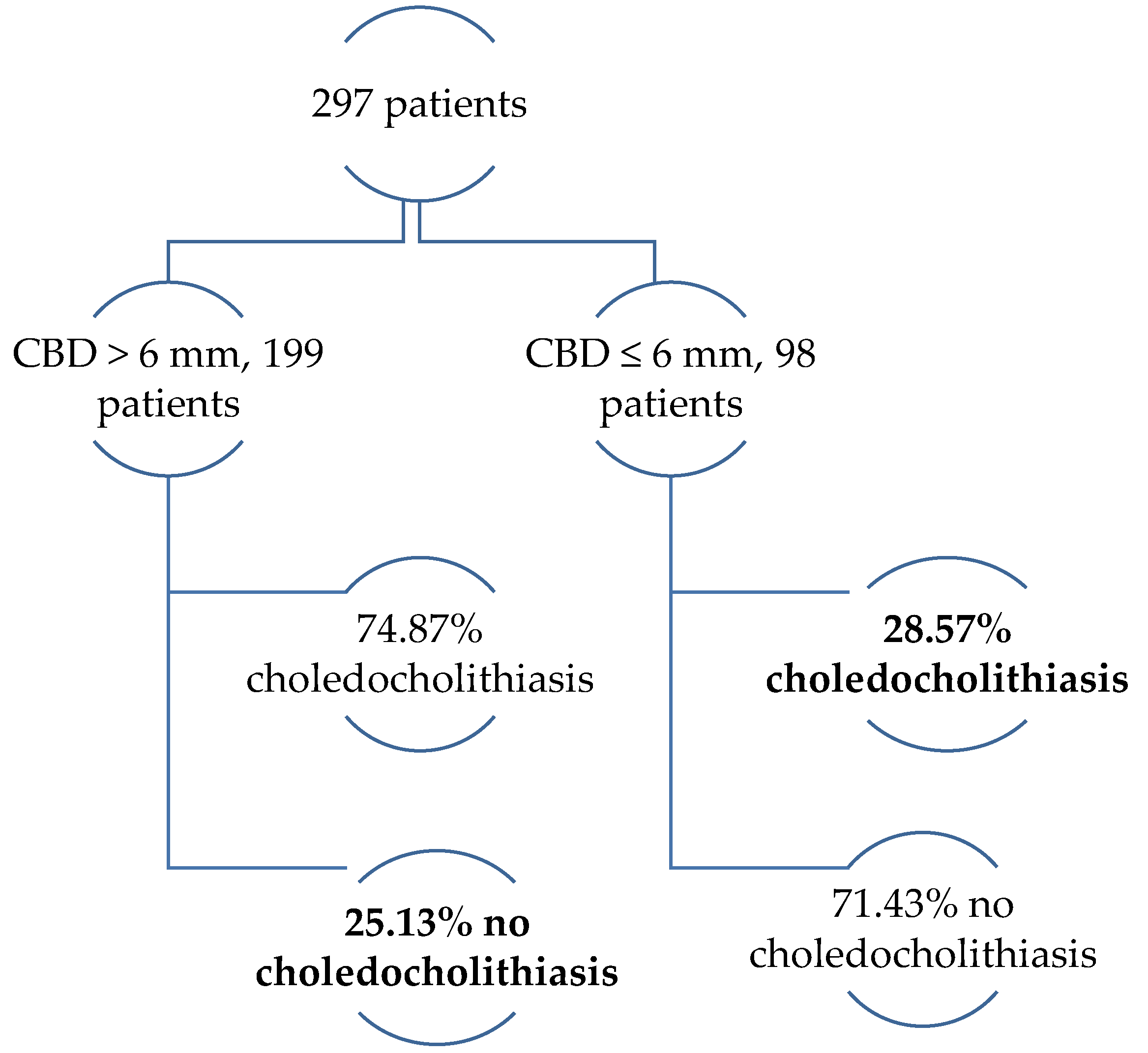

The study covers the period from 2012 to 2017; patients who were urgently admitted with signs and symptoms of complicated gallstone disease and a risk of choledocholithiasis were included prospectively [

8]. All patients were selected for laparoscopic cholecystectomy and laparoscopic ultrasonography (LUS) to prove or rule out choledocholithiasis. Complicated gallstone disease was suspected based on evidence of acute biliary pancreatitis, acute cholangitis or characteristic biliary colic, frequently accompanied by pale stools, dark urine and jaundice. Pre-operative diagnosis of cholangitis was based on the criteria recommended in the Tokyo Guidelines 2018. The evidence of systemic inflammatory response (increased WBC > 10 × 1000/µL or CRP more than 10 mg/L), cholestatic pattern, presented by abnormal liver function tests (alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ≥ 1.5 standard deviation) or bilirubin ≥ 34.2 µmol/L and gallstones in the gallbladder and/or dilation of the common bile duct >6 mm confirmed by trans-abdominal US, were the criteria for inclusion [

9,

10]. Biliary pancreatitis and cholangitis were diagnosed according to the revised Atlanta 2012 criteria (abdominal pain consistent with acute pancreatitis, serum lipase activity more than three times over the upper limit of normal) and characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on radiological investigations [

11]. The patient’s pre-operative overall physical condition was assessed using the adopted American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status classification system (ASA score) [

12,

13]. Patients with severe acute biliary pancreatitis or cholangitis who were not candidates for laparoscopic surgery and cases with converted operation to open surgery were excluded.

2.2. Pre-Operative Diagnosis of Choledocholithiasis

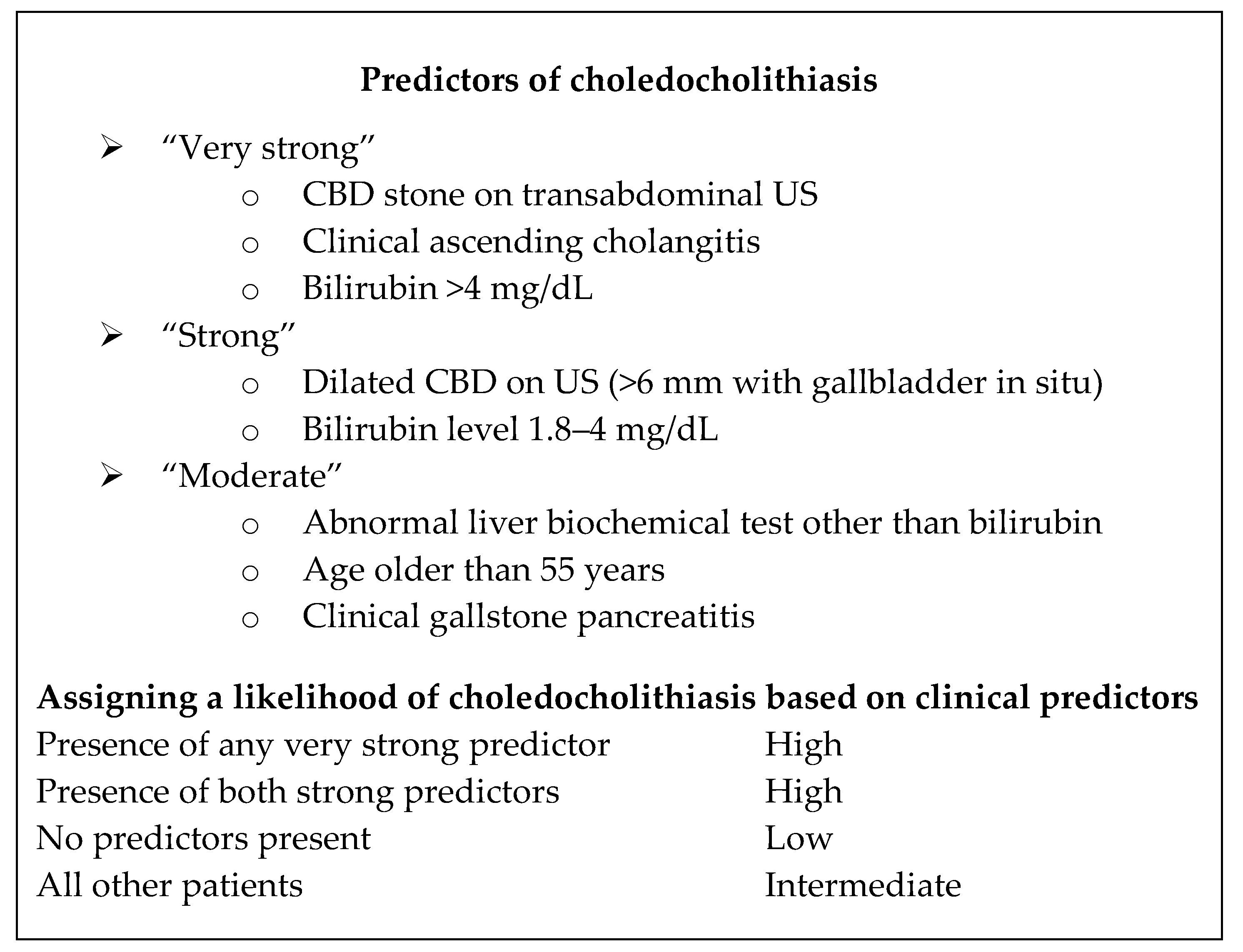

At the time of admission all patients underwent trans-abdominal ultrasound (TAUS). All TAUS examinations were performed by senior residents supervised by a certified radiologist. Gallstone disease was identified and possible choledocholithiasis or indirect signs of CBD stones, especially the dilation of the CBD more than 6 mm or the dilation of intrahepatic bile ducts were evaluated. According to availability, part of patients had pre-operative MRCP. Risk groups of choledocholithiasis were evaluated according to the ASGE guidelines (

Figure A1 in

Appendix A) [

14].

2.3. Laparoscopy and Laparoscopic Ultrasonography

Operations were performed by certified HPB surgeons of our department with a classic four-trocar approach. After the formation of pneumoperitoneum, trocars were positioned in the following way—10 mm through the umbilical ring for the camera and three for the manipulation—one of them 10 mm at the epigastrium proprium and two, 5 mm to the right side. Then the cystic duct was identified and clipped proximally close to the neck of the gallbladder. All LUS were done by a mobile ultrasound machine and a special, flexible probe for laparoscopic ultrasonography.

An ultrasound probe was inserted in the abdominal cavity through the epigastric trocar. Once the fundus part of the gallbladder was lifted over the liver, scanning began with a gallbladder examination. The common hepatic duct and common bile duct were scanned when the LUS probe was placed on the superior edge of the hepato-duodenal ligament and slid inferiorly to the distal end of the bile duct (

Figure 1).

The distal part of the common bile duct (retro-duodenal and intra-pancreatic) and the area of the papilla Vateri were scanned through the duodenum. The left and right hepatic ducts and their junction were investigated through the right hepatic lobe. The main metrics examined in the study were the maximum width of the bile duct, its content (gallstones), the maximum size and the quantity of the stones. Stones were considered as a positive finding on LUS or choledocholithiasis (

Figure 2), as well as biliary sludge in the lumen of the bile duct.

In case of choledocholithiasis, LCBDE was done following two main approaches—through the cystic duct and directly through the bile duct (ductotomy). The type of the bile duct clearance method was based on the LUS finding (size of the bile duct and stones, the number of stones). However, in cases with sludge in the bile duct, only rinsing without additional bile duct exploration was performed.

In all cases during surgery, biliary drainage function (main purpose) was completely restored. In cases of LCBDE failure or insufficient trans-papillary biliary drainage, choledochostoma (controlled biliary fistula) was left.

All patients with cholangiostomas had a fistulography (cholangiography) on the third day after surgery and only after the re-approval of choledocholithiasis or stenosis of the papilla, ERCP with endoscopic papillotomy was done. All choledochostomas were evacuated at the outpatient stage after the 10th postoperative day.

In cases with an extensive bile duct dilatation and stenosis of the papilla, choledocho-duodenostomies were performed only in patients over 60 years of age.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The interval data were expressed as a median (Me) with an interquartile range (IQR), because the breakdown of the data was asymmetric, confirmed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the interval data between the groups. Pearson χ2 and Fisher tests were used to compare the nominal data between the groups. The correlation between the pre-operative and total hospital stay and clinical data were calculated by the Spearman rho method. A logical regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with a longer hospital stay. The results were considered statistically significant at the p-value of <0.05 and a confidence interval of 95%. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS software (version 20) and MedCalc (version 15).

2.5. Ethics

The assessment and usage of all retrospective clinical data were approved and permitted before the study on the 15th of November 2018 by the Ethics Committee of Riga Stradins University (study No. 6–3/56). The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the “World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects” adopted by the 18th WMA General Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, June 1964 and amended by the 59th WMA General Assembly, Seoul, South Korea, October 2008 [

15].

4. Discussion

Choledocholithiasis is the main complication of gallstone disease and occurs in 11%–21% of patients during cholecystectomy [

2]. Recognition of choledocholithiasis requires an accurate and timely investigation due to the potentially serious and fatal complications of the disease. Despite the wide range of diagnostic possibilities, the detection of choledocholithiasis is still a major challenge for surgeons and radiologists. The bile duct stones may be predicted by the criteria of preoperative examination; however, the accuracy is not very high [

15,

16]. It is important to note that invasive diagnostic methods such as ERCP should not be routinely used in the visualization of choledocholithiasis. Due to the potentially severe complications of ERCP [

17] and costs, the indications for this method are very specific and can only be used for therapeutic purposes. MRCP is recommended as the main diagnostic method of complicated gallstone disease in many studies [

2]. The rationale for that recommendation is the non-invasiveness of the method, its high diagnostic accuracy and the ability to evaluate the biliary system and pancreas before surgery. On the other hand, some reports indicate an incomplete value of MRCP in patients with small stones in the bile duct. A recently published comparative study also points to the superiority of LUS over MRCP in the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis [

18]. Moreover, the availability of the MRCP is limited in many institutions and often is not available for all patients, as it was in our study where it was done in 29.3% of patients. The above-mentioned facts suggest that the optimal diagnostic management of choledocholithiasis is still to be clarified.

The incidence of choledocholithiasis increases with age and the overall risk is higher in elderly patients with severe comorbidities like in our study [

19,

20,

21].

Biochemical markers of the liver (ALT, AST, GGT, ALP) may be useful in predicting incomplete biliary drainage, including due to choledocholithiasis [

22], but there is no evidence of changes in these tests in all cases. Insignificant differences between liver transaminases in patients with and without choledocholithiasis were observed in this study. Reports from literature indicate that no specific imaging is required in cases with unchanged liver biochemical parameters and a non-dilated bile duct, because choledocholithiasis is not predictable [

16,

23]. However, the data of the current study suggest that a significant number of patients may also have stones in a non-dilated bile duct. The direct fraction of bilirubin and the total level of bilirubin were the only statistically significant biochemical indicators that increase in patients with choledocholithiasis. Other authors present similar data, suggesting that only the direct fraction of bilirubin is a very strong predictor of choledocholithiasis, and liver transaminases must be estimated very critically [

14].

Many authors suggest MRCP as a first-line diagnostic method of choledocholithiasis [

3,

24,

25,

26,

27]. In the existing guidelines (ASGE, 2010), MRCP is also recommended for patients with a medium (10%–50%) risk of choledocholithiasis [

14,

28]. MRCP was used in 23 (26.4%) patients of the medium-risk group in the present study. In other 64 (73.6%) patients who were at high risk for choledocholithiasis according to the criteria from the ASGE guidelines, choledocholithiasis was not found in 34. This finding does not comply with the ASGE recommendations to perform ERCP first in high-risk patients without any specific diagnostic modality before ERCP. A combined preoperative MRCP and LUS applied in the selected patient cohort allowed avoidance of unnecessary ERCP and possible complications related to that. There are similar observations published by other authors [

29,

30,

31].

According to the data from literature, MRCP has a high diagnostic value in the detection of choledocholithiasis [

32]; however, there are reports that indicate an insufficient diagnostic value of MRCP in cases with small stones and sludge in the common bile duct [

18]. The obtained data are similar—the size (median value) of the undiagnosed stones on preoperative MRCP was 3 mm, complying with the data from literature. However, the sensitivity and specificity of MRCP when the stone size was more than 1 mm reached 82.9% and 92%, respectively. Despite the discussions about the clinical relevance of bile sludge in the common bile duct, some authors have proven the role of sludge in the pathogenesis of biliary pancreatitis [

33] and cholangitis [

34], as well as a high risk of recidivism of biliary pancreatitis in case of undetected microlithiasis—33%–60%. Microlithiasis verified by LUS is important at the time of surgical intervention. It provides the possibility to flush the bile duct achieving duct clearance. However, there exists another opinion regarding microlithiasis, without any active treatment. This provides that in most of cases biliary sludge may pass through the papilla spontaneously. Several authors also report the significant value of LUS in the detection of sludge compared to other methods [

35]. In the current study, in 75.5% of patients choledocholithiasis was diagnosed by LUS considering all high-risk patients, according to the ASGE guidelines. The other 24.5% of patients had no stones in the bile duct. These patients also avoided unnecessary manipulations including ERCP. Unlike MRCP, the indications for possible postoperative ERCP are defined very clearly and precisely during surgery using LUS. If clearance of the bile duct fails, the operation is finished by the formation of cholangiostoma (controlled biliary fistula, mostly trans-cystic for biliary drainage). Postoperative cholangiography with a contrast agent is performed to clarify the condition of the biliary tree and possible evidence of stones for the clarification of the final indications for ERCP thereby minimizing unnecessary invasive procedures. According to the gained experience, the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis is reduced in patients with cholangiostoma due to the decompression of the biliary tree, the drainage of the bile and pancreatic juice. Other authors describe a similar experience [

36].

LUS is one of the newest intraoperative imaging methods of choledocholithiasis; it provides the operating surgeon with very precise information of the bile ducts with a very high diagnostic value. LUS is recommended in the ASGE guidelines in patients with a medium risk of choledocholithiasis (10%–50%) as one of the intraoperative imaging modalities without specific preoperative imaging [

14]. Similar to other authors, the diagnostic value of LUS in the current study was very high—99.4% sensitivity and 94.3% specificity. In the present study, the superiority of LUS over MRCP is related to the facts that MRCP may miss stones smaller than <5 mm, especially in patients with biliary pancreatitis [

2,

37]. In contrast, two cases of MRCP-verified choledocholithiasis were not confirmed by the LUS during laparoscopy. These two false-positive MRCP cases could be explained by the spontaneous trans-papillary migration of the gallstone to the duodenum in the time interval between MRCP and surgery. Other authors share a similar experience [

37]. There are reports presented that in up to a third of patients’ spontaneous migration of the gallstones to the duodenum before surgery may occur [

38], which is much more than in the present study. Therefore, by using LUS unnecessary LCBDE and complications related to it can be avoided. The diagnostic value of LUS in our study population was also superior to MRCP, similarly to the data presented by other authors [

18]. According to our experience, LUS provides the possibility to evaluate the permeability of the papilla Vateri, which was observed during the bile duct rinsing. It was also determined that turbulent movements of the fluid in the lumen of the descendent part of the duodenum can be observed. Good visualization is the cornerstone of surgery. LUS assists the surgeon, and at any time during the operation may quickly, accurately, safely help to control the anatomy so that patients are not exposed to the risk of an iatrogenic lesion of any structures [

39,

40]. The experience confirms the same; thus, there were no iatrogenic lesions of the bile ducts in patients of the selected study population.