Existential Suffering in Palliative Care: An Existential Positive Psychology Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

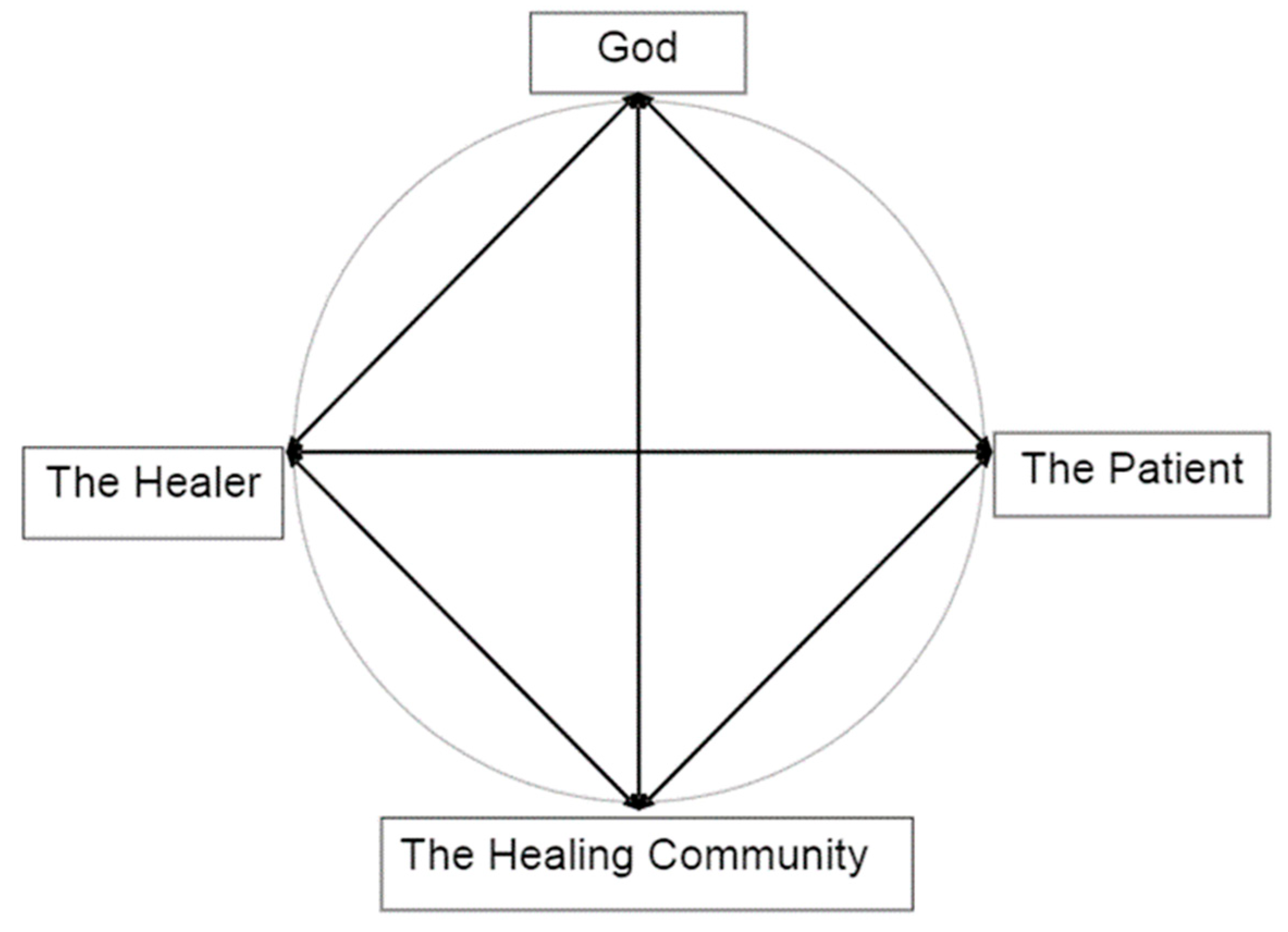

1.1. A Holistic Model of Compassionate Care

1.2. Why Is Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0) Important for Palliative Care

2. Existential Suffering and Palliative Care

2.1. A Developmental Perspective

“Living well and dying well involve enhancing one’s sense of self, one’s relationships with others, and one’s understanding of the transcendent, the spiritual, the supernatural…And only in confronting the inevitability of death does one truly embrace life.”

2.2. Existential Suffering and the Quest for Meaning

- (1)

- “Negatively oriented search for meaning—the Why and How questions that increase our ability to understand the cause and reason of unpleasant and unexpected events in order to meet our needs to predict, control and justify them. It represents the lay scientist and lay philosopher in each of us [42,43].

- (2)

2.3. The Desire to Hasten Death and Physician-Assisted Suicide

“Even with all my suffering I am still opposed to Kevorkian, who takes people’s lives prematurely simply because they are in pain or are uncomfortable. He does not understand that he deprives people of whatever last lessons they have to learn before they can graduate. Right now I am learning patience and submission. As difficult as those lessons are, I know that the Highest of the High has a plan. I know that He has a time that will be right for me to leave my body the way a butterfly leaves its cocoon. Our only purpose in life is growth.”(p. 281)

3. Recent Research on Existential Anxieties and Wellbeing in Palliative Patients

3.1. Death-Related Anxieties

3.2. Grief

3.3. Isolation and Loneliness

3.4. Dignity Related Existential Distress (DR-ED)

3.5. Regrets

4. Integrative Meaning Therapy (IMT) in Palliative Care

4.1. Meaning-Centered Approach to End-of-Life Care

- Session 1—Concepts of meaning and sources of meaning

- Session 2—Cancer and meaning

- Sessions 3 and 4—Meaning derived from the historical context of life

- Session 5—Meaning derived from attitudinal values

- Session 6—Meaning derived from creative values and responsibility

- Session 7—Meaning derived through experiential values

- Session 8—Termination and feedback.

4.2. Wong’s Pioneering Work on Death Acceptance

4.3. Meaning Management and Death Acceptance

4.4. Some Key Concepts of IMT in Palliative Care

- Wong’s Definition of Meaning. Meaning has been defined by different researchers differently. Wong [39] proposes that a comprehensive way to clarify the concept of meaning is PURE (purpose, understanding, responsibility, and enjoyment):

- (a)

- A meaningful life is purposeful. We all have the desire to be significant, we all want our lives to matter. The intrinsic motivation of striving to improve ourselves to achieve a worth goal is a source of meaning (as in the movie Ikiru). That is why purpose is the cornerstone of a meaningful life. Even if you want to live an ordinary life, you can still do your best to improve yourself as a good parent, spouse, neighbor, or a decent human being.

- (b)

- A meaningful life is understandable or coherent. We need to know who we are, the reasons for our existence, or the reason or objective of our actions [100]. Having a cognitive understanding or a sense of coherence is equally important for meaning.

- (c)

- A meaningful life is a responsible one. We must assume full responsibility for our life or for choosing our life goal. Self-determination is based on the responsible use of our freedom. This involves the volition aspect of personality. That is why for both Frankl [44] and Peterson [37] have noted that responsibility equals meaning.

- (d)

- A meaningful life is enjoyable and fulfilling. It is the deep life satisfaction that comes from having lived a good life and made some difference in the world. This is a natural by-product of self-evaluation that “my life matters”.

- 2.

- The Golden Triangle of Faith, Hope, and Love: We have a serious mental health crisis because we are like fish out of water, living in a materialistic consumer society and a digital world without paying much attention to our spiritual needs. Technological progress contributes to our physical wellbeing, but it also destroys the soul if we do not make an intentional effort to care for our soul. IMT aims to help people get back into the water—to meet people’s basic psychological needs for loving relationships, a meaningful life, and faith in God and some transcendental values, as shown in the symbol of the Golden Triangle (Figure 5).

- (a)

- The power of IMT is derived from faith—faith in a better future, in the self, in others, in God, and in a happy afterlife. It does not matter whether you have faith in Jesus, Buddha, or in your medical doctors. If you have faith in someone or something greater than yourself, you will have a better chance of overcoming seemingly insurmountable problems. Faith, nothing but faith, can counteract the horrors of life and death. For Frankl, faith is the key to healing:“The prisoner who had lost faith in the future—his future—was doomed. With his loss of belief in the future he also lost his spiritual hold; he let himself decline and become subject to mental and physical decay.”([44], p. 95)

- (b)

- Hope represents one’s role as an agent to discover one’s true calling and work towards a better future. Even palliative care patients can work towards a better tomorrow. The saddest thing my (the first author) father said to me during my last visit to Hong Kong was “I have no hope. I’m going to die soon, and none of my children are interested in taking over my business”. This was because he had no hope beyond his own personal interest. Tragic optimism [103,104] enables one to transcend such hopelessness.

- (c)

- Love for others and developing connections indicate that we are always part of a larger whole, and relationships are a major source of meaning of life [105]. By withholding love, people perish due to loneliness and meaninglessness. Do we realize that love is the most powerful force on earth? Do we know that love can give us the strength to endure anything, the courage to face any danger, and the joy to make sacrifices for others?

- 3.

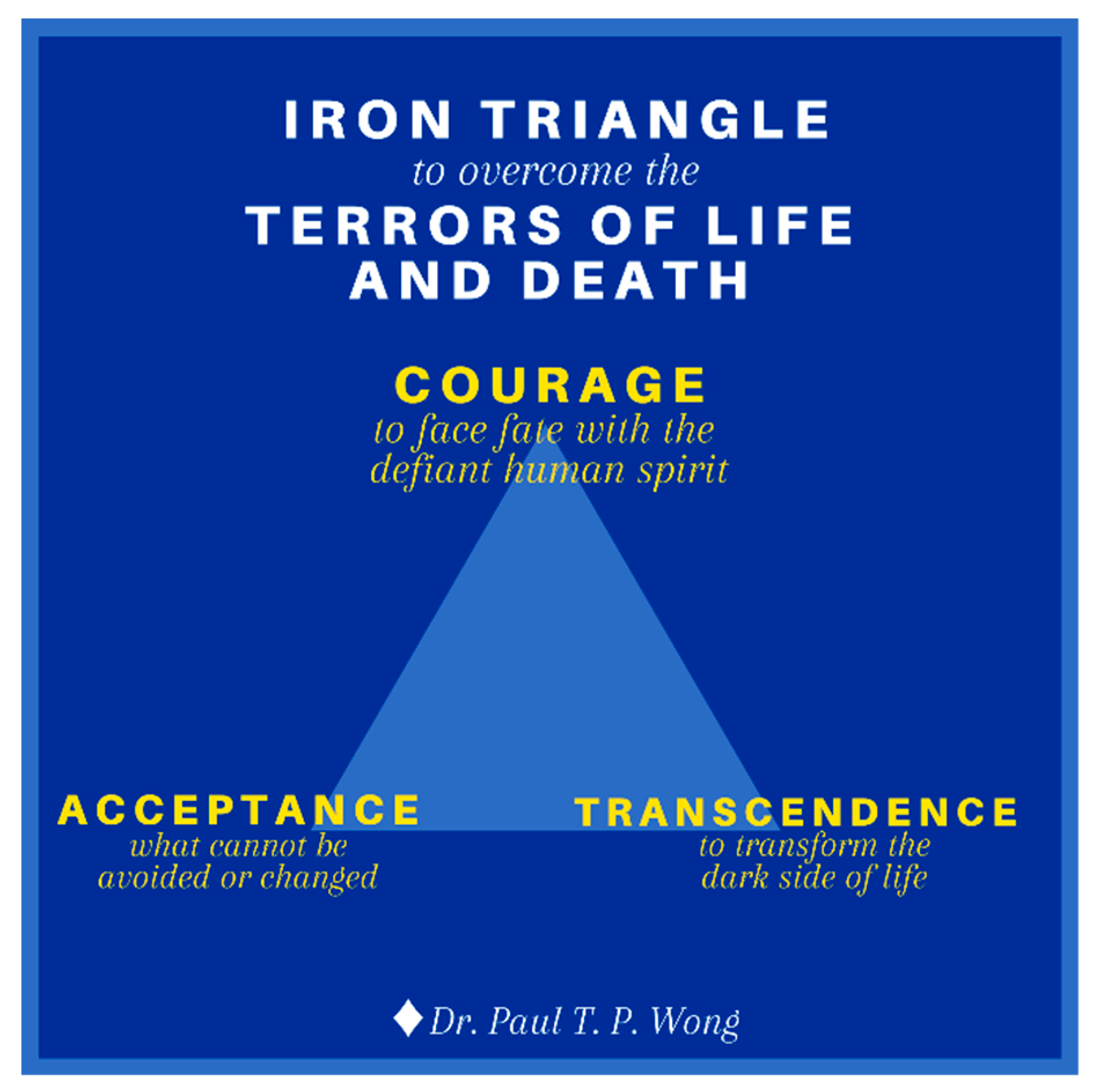

- The Iron Triangle of Courage, Acceptance, and Transformation. Life is tough, especially during old age with all the inevitable losses. During the end-of-life stage, one needs a lot of courage to face all the challenges associated with death and dying [106]. One needs courage to cope with the distress of sickness and dying, to accept all the losses, and for the final exit. One also needs courage to connect with their own inner resources, family, and community in order to enhance their dignity and well-being. The main thrust of my (the first author) recent book [107] is that we are wired in such a way that our genes and brain have the necessary capacities to survive and thrive in any adverse situations, provided that we are awakened to our spiritual nature and cultivate our psychological resources. In addition to the golden triangle, our other resources come from the iron triangle of courage, acceptance, and transcendence as shown in Figure 6.

- (a)

- Existential courage is the courage “necessary to make being and becoming possible” ([108], p. 4). As discussed earlier, existential courage is needed in all stages of human development: The courage to embrace the dark side of human existence makes it possible for us make positive changes, to face what cannot be changed or is beyond our control, and to transform all the setbacks and obstacles. The most comprehensive treatment of courage can be found in Yang et al. [109]. They treat courage as a spiritual concept “similar to the existential thoughts of the will to power.” (p. 13). In their words, “To Adler, the will to power is a process of creative energy or psychological force desiring to exert one’s will in overcoming life problems.” (p. 12). Courage is also similar to Frankl’s [44] defiant power of the human spirit.

- (b)

- Death acceptance is the other side of life acceptance. David Kuhl [111] writes:

- (c)

- There are different pathways in transforming negative events and emotions into wellbeing [112,113]. Transformative coping takes on different forms, such as reframing, re-authoring, or recounting one’s life event in terms of a larger narrative or meta-story. For palliative care patients, life review or reminiscence [42] and small self-transcendental acts, as shown in Ikiru, seems most helpful. In life review, we ask patients to reflect on the following questions: What are your happiest moments (with someone special in your life)? What is your best early memory? What are your proudest moments (for your achievement and contribution)? What are your most meaningful moments?

- 4.

- Some Practical Tips in Palliative Counselling. Here are some practical tips to help transform a victim’s journey into a hero’s adventure and discover meaning and hope in boundary situations. IMT seeks to awaken the client’s sense of responsibility and meaning, and guide them to (a) achieve a deeper understanding of the problems from a larger perspective and (b) discover their true identity and place in the world.

- The healing silence—listening to the inner voice.

- The healing touch—touching the heart and soul.

- The healing connection—establishing an I–You relationship.

- The healing presence—providing a caring, compassionate presence.

- The healing process—nurturing spiritual growth.

- (1)

- Do some random acts of kindness to others.

- (2)

- Engage in creative or worthwhile work as a gift to the community or family.

- (3)

- Reach out to get reconciled with estranged loved ones.

- (4)

- Make a useful contribution to society.

- (5)

- Be true to oneself and do something one has always wanted to do.

- (6)

- Construct a coherent life story with photos as a legacy to one’s family.

- I believe that life has meaning until my last breath.

- I am grateful that the reality of suffering and death has showed me what I was meant to be.

- I can live a happy and meaningful life until my last breath.

- Life has been very tough but I am grateful that I have overcome its obstacles.

- I have my regrets but I have found forgiveness.

- Show compassion through gentle touch (e.g., holding hand) and smile.

- Ask them if there is anything you can do for them.

- Ask them about any concerns (e.g., someone they want to see).

- Help them see that they have lived a life of meaning and purpose.

- Assure them their life stories are worth telling and remembering.

- Assure them they have made a difference in the lives of others.

- Assure them they can still have hope beyond death through faith.

- Assure them that they can accept death with inner peace.

- Offer a prayer if it seems appropriate.

5. Conclusions

“Every society can be best judged by how it treats its vulnerable citizens. The progress of a civilization can be measured not only by technological advancements, but also by progress in the humane treatment of those who cannot help themselves. Therefore, hospice and palliative care represents one of the highest achievements of Christian civilization.”[106]

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hannon, B.; Mak, E.; Al Awamer, A.; Banerjee, S.; Blake, C.; Kaya, E.; Lau, J.; Lewin, W.; O’Connor, B.; Saltman, A.; et al. Palliative care provision at a tertiary cancer center during a global pandemic. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2501–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oluyase, A.O.; Hocaoglu, M.; Cripps, R.L.; Maddocks, M.; Walshe, C.; Fraser, L.K.; Preston, N.; Dunleavy, L.; Bradshaw, A.; Murtagh, F.E.; et al. The Challenges of Caring for People Dying from COVID-19: A Multinational, Observational Study (CovPall). J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrana, T.; De Lima, L.; Pettus, K.; Ramsey, A.; Napier, G.; Wenk, R.; Radbruch, L. The impact of COVID-19 on palliative care workers across the world: A qualitative analysis of responses to open-ended questions. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 19, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentlandt, K.; Cook, R.; Morgan, M.; Nowell, A.; Kaya, E.; Zimmermann, C. Palliative Care in Toronto During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.; Ribeiro, O.; Teixeira, L.; Paúl, M.C. Successful aging at 100 years: The relevance of subjectivity and psychological resources. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T. Personal meaning and successful aging. Can. Psychol. Can. 1989, 30, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.-C.P.; Lau, H.-P.B.; Kwok, C.-F.N.; Leung, Y.-M.A.; Chan, M.-Y.G.; Chan, W.-M.; Cheung, S.-L.K. The well-being of community-dwelling near-centenarians and centenarians in Hong Kong a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.M. The Role of Spirituality in Health Care. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2001, 14, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byock, I. The Best Care Possible: A Physician’s Quest to Transform Care through the End of Life; Avery: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Compassionate and Spiritual Care: A Vision of Positive Holistic Medicine. International Network on Personal Meaning. 2004. Available online: http://www.meaning.ca/archives/archive/pdfs/wong-spiritual-care.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Newman, K.M. Eight Acts of Goodness Amid the COVID-19 Outbreak. Greater Good Magazine. Available online: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/eight_acts_of_goodness_amid_the_covid_19_outbreak (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Sweet, J. How Random Acts of Kindness Can Boost Your Health during the Pandemic. VeryWell Mind. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/how-random-acts-of-kindness-can-boost-your-health-5105301 (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Wong, P.T.P. Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Can. Psychol. Can. 2011, 52, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. The president’s address. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 559–562. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Second wave positive psychology’s (PP 2.0) contribution to counselling psychology. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2019, 32, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P. The maturing of positive psychology and the emergence of PP 2.0: A book review of Positive Psychology (3rd ed.) by William Compton and Edward Hoffman. Int. J. Wellbeing 2020, 10, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P. Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0) and global wellbeing: Why it is Necessary during the Age of COVID-19. Int. J. Existent. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Mayer, C.-H.; Arslan, G. Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0) and the new science of flourishing through suffering [editorial]. Frontiers 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Beyond Happiness and Success: The New Science of self-Transcendence [Keynote]. In Proceedings of the International Network on Personal Meaning 11th Biennial International Meaning Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–8 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Toward a Dual-Systems Model of What Makes Life Worth Living. In The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Wong, P.T.P., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, S. Sources of Suffering: Fear, Greed, Guilt, Deception, Betrayal, and Revenge; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tomer, A.; Eliason, G.T.; Wong, P.T.P. (Eds.) Existential and Spiritual Issues in Death Attitudes; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yalom, I.D. Staring at the sun: Overcoming the terror of death. Humanist. Psychol. 2008, 36, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Bowers, V. Mature Happiness and Global Wellbeing in Difficult Times. In Scientific Concepts behind Happiness, Kindness, and Empathy in Contemporary Society; Silton, N.R., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 112–134. [Google Scholar]

- Carreno, D.F.; Eisenbeck, N.; Pérez-Escobar, J.A.; García-Montes, J.M. Inner Harmony as an Essential Facet of Well-Being: A Multinational Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, B.D. The Joyful Life: An Existential-Humanistic Approach to Positive Psychology in the Time of a Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Arslan, G.; Bowers, V.L.; Peacock, E.J.; Kjell, O.N.E.; Ivtzan, I.; Lomas, T. Self-transcendence as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering: The development and validation of the self-transcendence measure-B. Frontiers 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, C.; Hales, S.; Jung, J.; Chiu, A.; Panday, T.; Rydall, A.; Nissim, R.; Malfitano, C.; Petricone-Westwood, D.; Zimmermann, C.; et al. Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM): Phase 2 trial of a brief individual psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Palliat. Med. 2013, 28, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissim, R.; Freeman, E.; Lo, C.; Zimmermann, C.; Gagliese, L.; Rydall, A.; Hales, S.; Rodin, G. Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM): A qualitative study of a brief individual psychotherapy for individuals with advanced cancer. Palliat. Med. 2011, 26, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Khait, A.; Sabo, K.; Shellman, J. Analysis and Evaluation of Reed’s Theory of Self-Transcendence. Res. Theory Nurs. Pr. 2020, 34, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psych-Mental Health NP. (n.d.). Pamela Reed’s Theory of Self-Transcendence. Pmhealthnp.com. Available online: https://pmhealthnp.com/pamela-reeds-theory-of-self-transcendence/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E.H. The Life Cycle Completed; Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, P.G.; Pamela, G. Reed: Self-transcendence theory. In Nursing Theorists and Their Work, 9th ed.; Alligood, M.R., Ed.; Mosby Elsevier: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 463–476. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Currier, J.M.; Coleman, R.; Tomer, A.; Samuel, E. Confronting Suffering and Death at the End of Life: The Impact of Religiosity, Psychosocial Factors, and Life Regret Among Hospice Patients. Death Stud. 2011, 35, 777–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, B. The Top Five Regrets of the Dying: A Life Transformed by the Dearly Departing; Hay House: Carlsbad, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.B. 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos; Random House Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; ISBN 978-0-345-81602-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tolstoy, L. The Death of Ivan Ilych. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998, 128, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Gingras, D. Finding Meaning and Happiness While Dying of Cancer: Lessons on Existential Positive Psychology. PsycCritiques 2010, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V. The Doctor and the Soul: From Psychotherapy to Logotherapy; Second Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Meaning and evil and a two-factor model of search for meaning [Review of the essay Meaning and Evolution, by R. Baumeister & W. von Hippel]. Evol. Stud. Imaginative Cult. 2020, 4, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.; Watt, L.M. What types of reminiscence are associated with successful aging? Psychol. Aging 1991, 6, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Weiner, B. When people ask “Why” questions and the heuristic of attributional search. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 40, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V.E. Man’s Search for Meaning; Washington Square Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Self-Transcendence: A Paradoxical Way to Become Your Best. Int. J. Existent. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 6, 9. Available online: http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Wong, P.T.P. Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In Clinical Perspectives on Meaning: Positive and Existential Psychotherapy; Russo-Netzer, P., Schulenberg, S.E., Batthyány, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 323–342. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, C.; Hales, S.; Zimmermann, C.; Gagliese, L.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G. Measuring Death-related Anxiety in Advanced Cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. 2011, 33, S140–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chochinov, H.M.; Hassard, T.; McClement, S.; Hack, T.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Harlos, M.; Sinclair, S.; Murray, A. The Patient Dignity Inventory: A Novel Way of Measuring Dignity-Related Distress in Palliative Care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 36, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterman, A.H.; Fitchett, G.; Brady, M.J.; Hernandez, L.; Cella, D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, L.; Teixeira, L.; Afonso, R.M.; Ribeiro, O. To live or die: What to wish at 100 years and older. Frontiers 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lemmens, T. Should assisted dying for psychiatric disorders be legalized in Canada? Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2016, 188, E337–E339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bikenbach, J.E. Disability and Life-Ending Decisions; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P.; Moss, M.; Hoffman, C.; Kleban, M.H.; Ruckdeschel, K.; Winter, L. Valuation of Life. J. Aging Health 2001, 13, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.; Guenther, M. Restoration and re-creation: Spirituality in the lives of healthcare professionals. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2012, 6, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Stiller, C. Living with dignity and palliative counselling. In End of Life Issues: Interdisciplinary and Multidimensional Perspectives; de Vries, B., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 1999; pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Byock, I.R. When Suffering Persists …. J. Palliat. Care 1994, 10, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, J.E. When Is It Right to Die? Suicide, Euthanasia, Suffering, Mercy; Zondervan Pub: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kübler-Ross, E. On Death and Dying; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gaignard, M.-E.; Hurst, S. A qualitative study on existential suffering and assisted suicide in Switzerland. BMC Med. Ethics 2019, 20, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrie, D. Tackling Existential Distress in Palliative Care. News GP. Available online: https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/tackling-existential-distress-in-palliative-care (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Tarbi, E.; Gramling, R.; Bradway, C.; Meghani, S. “If It’s the Time, It’s the Time”: Existential Communication in Naturally Occurring Palliative Care Conversations with Individuals with Advanced Cancer, Their Families, and Clinicians (RP307). J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.; Lin, J.; Gagliese, L.; Zimmermann, C.; Mikulincer, M.; Rodin, G. Age and depression in patients with metastatic cancer: The protective effects of attachment security and spiritual wellbeing. Ageing Soc. 2009, 30, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, M.; Strasser, F.; Gamondi, C.; Braunschweig, G.; Forster, M.; Kaspers-Elekes, K.; Veri, S.W.; Borasio, G.D.; Pralong, G.; Pralong, J.; et al. Relationship Between Spirituality, Meaning in Life, Psychological Distress, Wish for Hastened Death, and Their Influence on Quality of Life in Palliative Care Patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.; Walsh, A.; Mikulincer, M.; Gagliese, L.; Zimmermann, C.; Rodin, G. Measuring attachment security in patients with advanced cancer: Psychometric properties of a modified and brief Experiences in Close Relationships scale. Psycho-Oncology 2009, 18, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehling, S.; Tian, Y.; Malfitano, C.; Shnall, J.; Watt, S.; Mehnert, A.; Rydall, A.; Zimmermann, C.; Hales, S.; Lo, C.; et al. Attachment security and existential distress among patients with advanced cancer. J. Psychosom. Res. 2019, 116, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, L.; Strang, P. Existential Concerns of Families of Late-Stage Dementia Patients: Questions of Freedom, Choices, Isolation, Death, and Meaning. J. Palliat. Med. 2003, 6, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.D.; Moore, J.M.; Garza, C.J. Meaning in life and self-esteem help hospice nurses withstand prolonged exposure to death. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 27, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehling, S.; Malfitano, C.; Shnall, J.; Watt, S.; Panday, T.; Chiu, A.; Rydall, A.; Zimmermann, C.; Hales, S.; Rodin, G.; et al. A concept map of death-related anxieties in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2017, 7, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, S.; Rydall, A.; Hales, S.; Rodin, G.; Lo, C. Initial Validation of the Death and Dying Distress Scale for the Assessment of Death Anxiety in Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 49, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, E.; Lo, C.; Hales, S.; Zimmermann, C.; Rodin, G. Demoralization and death anxiety in advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 2566–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, P.J. Article Commentary: Grief and Palliative Care: Mutuality. Palliat. Care Res. Treat. 2013, 7, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.L.; Wladkowski, S.; Gibson, A.; White, P. Grief during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Considerations for Palliative Care Providers. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, e70–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuelke, T.; Crawford, C.; Kentor, R.; Eppelheimer, H.; Chipriano, C.; Springmeyer, K.; Shukraft, A.; Hill, M. Current Grief Support in Pediatric Palliative Care. Children 2021, 8, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute on Aging (n.d.). Mourning the Death of A Spouse. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/mourning-death-spouse (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Mah, K. Existential loneliness and the importance of addressing sexual health in people with advanced cancer in palliative care. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 1354–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyatanga, B. Being lonely and isolated: Challenges for palliative care. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2017, 22, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B. Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: A global challenge. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2020, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedini, N.C.; Choi, H.; Wei, M.Y.; Langa, K.M.; Chopra, V. The Relationship of Loneliness to End-of-Life Experience in Older Americans: A Cohort Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, M.; Blomqvist, K.; Edberg, A.; Rämgård, M. The context of care matters: Older people’s existential loneliness from the perspective of healthcare professionals-A multiple case study. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2019, 14, e12234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, H.; Trivedi, N.; Trivedi, V.; Moorthy, A. COVID-19: The disease of loneliness and solitary demise. Futur. healthc. J. 2021, 8, e164–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovero, A.; Sedghi, N.A.; Opezzo, M.; Botto, R.; Pinto, M.; Ieraci, V.; Torta, R. Dignity-related existential distress in end-of-life cancer patients: Prevalence, underlying factors, and associated coping strategies. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 2631–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Complete Care Coordination. How the Death of A Spouse Can Affect the Elderly. 2021. Available online: https://www.completecare.ca/blog/death-spouse-can-affect-elderly/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Breitbart, W.; Poppito, S.; Rosenfeld, B.; Vickers, A.; Li, Y.; Abbey, J.; Olden, M.; Pessin, H.; Lichtenthal, W.; Sjoberg, D.; et al. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Individual Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbart, W.; Rosenfeld, B.; Gibson, C.; Pessin, H.; Poppito, S.; Nelson, C.; Tomarken, A.; Timm, A.K.; Berg, A.; Jacobson, C.; et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology 2009, 19, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chochinov, H.M.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Breitbart, W.; McClement, S.; Hack, T.; Hassard, T.; Harlos, M. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, T.F.; McClement, S.; Chochinov, H.M.; Cann, B.J.; Hassard, T.H.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Harlos, M. Learning from dying patients during their final days: Life reflections gleaned from dignity therapy. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbart, W.; Applebaum, A. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy. In Handbook of Psychotherapy in Cancer Care; Watson, M., Kissane, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart, W.; Poppito, S. Individual Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Treatment Manual; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart, W.; Gibson, C.; Poppito, S.R.; Berg, A. Psychotherapeutic Interventions at the End of Life: A Focus on Meaning and Spirituality. Can. J. Psychiatry 2004, 49, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesser, G.; Wong, P.T.P.; Reker, G.T. Death Attitudes across the Life-Span: The Development and Validation of the Death Attitude Profile (DAP). Omega J. Death Dying 1988, 18, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Reker, G.T.; Gesser, G. Death Attitude Profile–Revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death. In Death Anxiety Handbook: Research Instrumentation and Application; Neimeyer, R.A., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bethune, B. Why So Many People—Including Scientists—Suddenly Believe in an Afterlife: Heaven is Hot Again, and Hell is Colder Than Ever. Maclean’s. Available online: http://www.macleans.ca/society/life/the-heaven-boom/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Wong, P.T.P. Living with Cancer, Suffering, and Death: A Case for PP 2.0. (Autobiography, Ch. 27). DrPaulWong.com. Available online: http://www.drpaulwong.com/living-with-cancer-suffering-and-death-a-case-for-pp-2-0-autobiography-ch-27/ (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Wong, P.T.P. A meaning-centered approach to overcoming loneliness during hospitalization, old age, and dying. In Addressing Loneliness: Coping, Prevention and Clinical Interventions; Sha’ked, A., Rokach, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Meaning management theory and death acceptance. In Existential and Spiritual Issues in Death Attitudes; Tomer, A., Eliason, G.T., Wong, P.T.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Tomer, A. Beyond Terror and Denial: The Positive Psychology of Death Acceptance. Death Stud. 2011, 35, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.T.P. What is the meaning mindset? Int. J. Existent. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. (Ed.) The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Existential positive psychology and integrative meaning therapy. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 32, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. The Jossey-Bass Social and Behavioral Science Series and the Jossey-Bass Health Series. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- George, L.S.; Park, C.L. Meaning in Life as Comprehension, Purpose, and Mattering: Toward Integration and New Research Questions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2016, 20, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Steger, M.F. The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.M.; Arslan, G.; Wong, P.T.P. Tragic Optimism as a Buffer against COVID-19 Suffering and the Psychometric Properties of a Brief Version of the Life Attitudes Scale (LAS-B). Frontiers 2021, 12, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P. Compassion: The hospice movement. In The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization; Kurian, G., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile. In The Human Quest for Meaning: A Handbook of Psychological Research and Clinical Applications; Wong, P.T.P., Fry, P., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 111–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Meaning Therapy: An Integrative and Positive Existential Psychotherapy. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2009, 40, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P. Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19; INPM Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- May, R. The Courage to Create; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Milliren, A.; Blagen, M. The Psychology of Courage: An Adlerian Manual of Healthy Social Living; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Worth, P. The deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity. Psychol. Educ. 2017, 54, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl, D. What Dying People Want: Practical Wisdom for the End of Life; Anchor Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Wenzel, A. Coping and Stress. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Abnormal and Clinical Psychology; Wenzel, A., Ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 886–890. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Wong, L.C.J.; Scott, C. Beyond stress and coping: The positive psychology of transformation. In Handbook of Multicultural Perspectives on Stress and Coping; Wong, P.T.P., Wong, L.C.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, A.M. Introduction to The Disciplinefor Pastoral Care Giving. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2000, 10, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.; Pargament, K.; Faigin, C. Sustained by the sacred: Religious and spiritual factors for resilience in adulthood and aging. In Resilience in Aging; Resnick, B., Gwyther, L.P., Roberto, K.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 191–214. [Google Scholar]

| Stage | Age | Existential Crisis | Main Task | Gains | Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infancy | Birth–2 years | Separation anxiety | Necessary gradual separation from mother |

|

|

| Preschooler | 3–4 years | Safety anxiety (Fear of getting hurt) | Testing limits of autonomy |

|

|

| Kindergarten to primary school | 4–12 years | Social anxiety (Fear of not belonging) | School |

|

|

| Adolescence | 12–18 years | Identity crisis |

|

|

|

| Young adult or early career | 19–25 | Independence anxiety |

|

|

|

| Adult or mid-career | 25–40 | Achievement anxiety (Fear of failure in career and marriage) |

|

|

|

| Mature adult or late career | 40–60 | Mid-life crisis |

|

|

|

| Early old age | 60–75 | Ultimate concerns about boredom and meaninglessness | Retirement |

|

|

| Late old age | 76–death | Worrying about unfinished business | Completing the race gracefully |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, P.T.P.; Yu, T.T.F. Existential Suffering in Palliative Care: An Existential Positive Psychology Perspective. Medicina 2021, 57, 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57090924

Wong PTP, Yu TTF. Existential Suffering in Palliative Care: An Existential Positive Psychology Perspective. Medicina. 2021; 57(9):924. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57090924

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Paul T. P., and Timothy T. F. Yu. 2021. "Existential Suffering in Palliative Care: An Existential Positive Psychology Perspective" Medicina 57, no. 9: 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57090924

APA StyleWong, P. T. P., & Yu, T. T. F. (2021). Existential Suffering in Palliative Care: An Existential Positive Psychology Perspective. Medicina, 57(9), 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57090924