Comparison of Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer in Uzbekistan and Korea: The First Report of The Uzbekistan–Korea Oncology Consortium

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Cancer Statistics of Uzbekistan from Global Perspective

2. Breast Cancer

2.1. Incidence and Mortality

2.2. Benefits of Screening

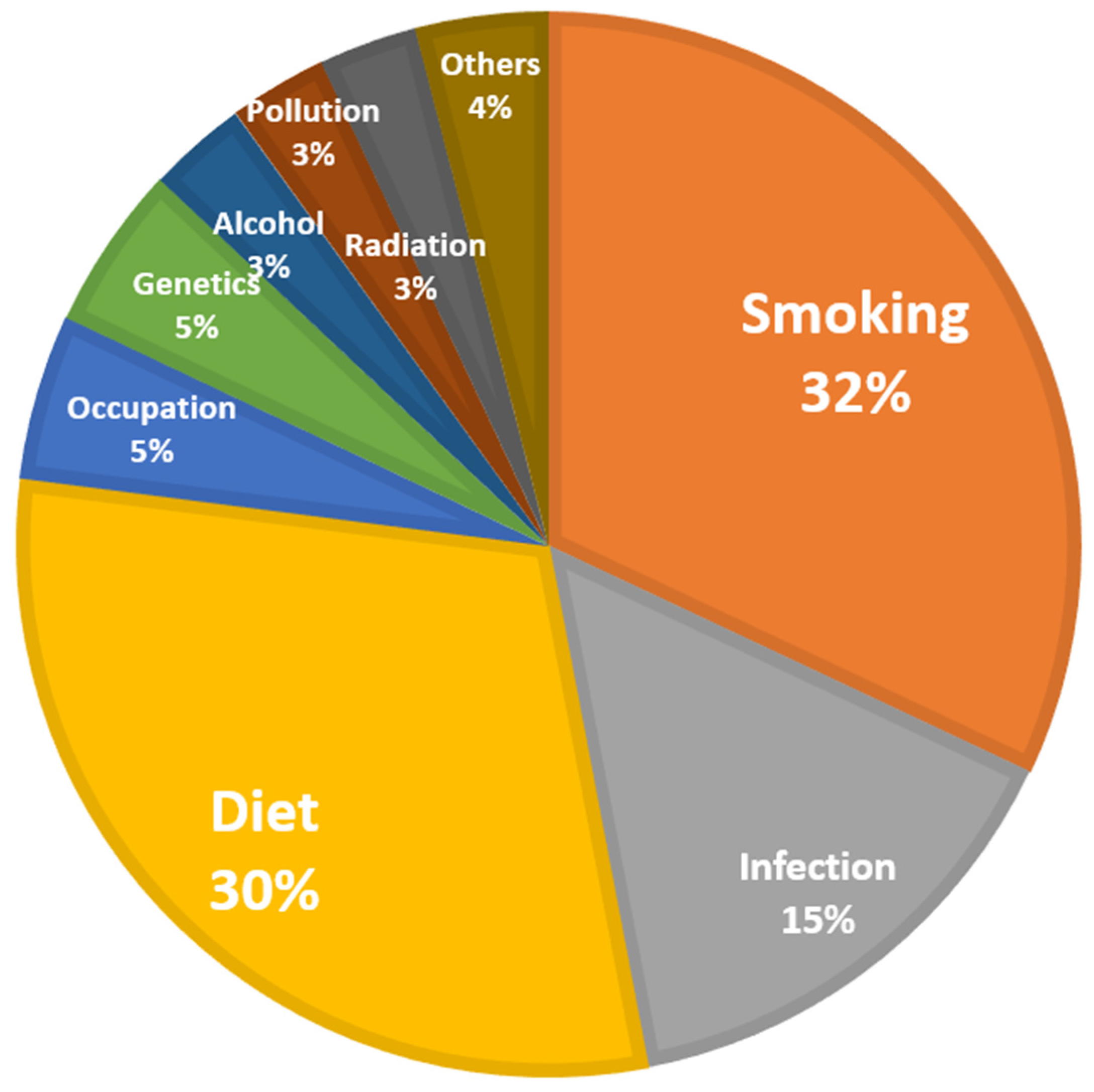

2.3. Identify the Cause of Breast Cancer

2.4. Advice on Treatment

2.5. Summary and Suggestions

3. Cervical Cancer

3.1. Incidence and Mortality

3.2. Cause of Cervical Cancer

3.3. HPV and Vaccination

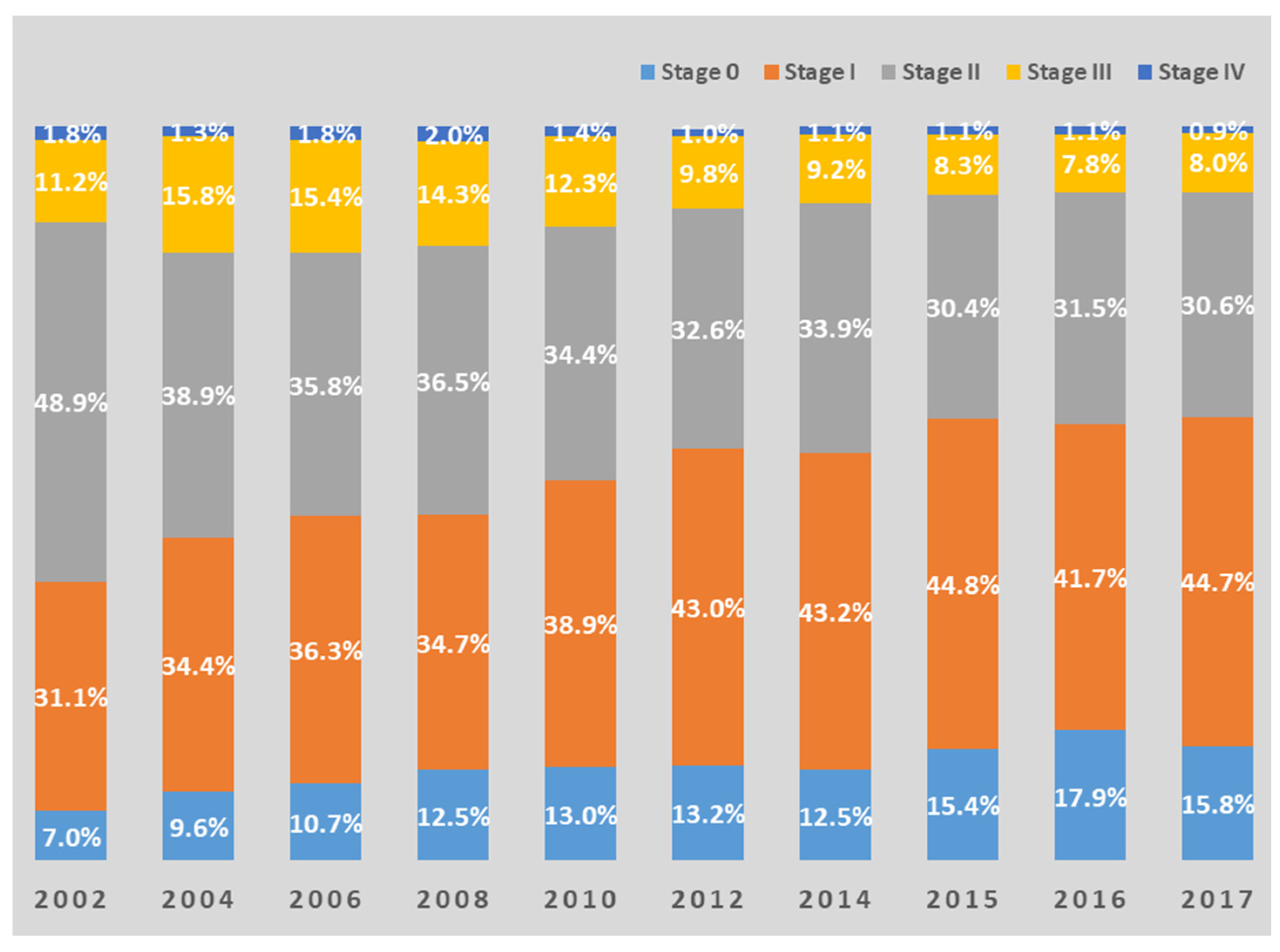

3.4. Benefits of Early Screening and Examples in Korea

3.5. Advice on Treatment

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stanton, E.A. The Human Development Index: A History; PERI Working Papers: Amherst, MA, USA, 2007; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, C.; Pompei, F.; Wilson, R. Peak and decline in cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence at old ages. Cancer 2012, 118, 1371–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillyashaykhov, M.; Djanklich, S.; Ibragimov, S.N.; Imamov, O. Analysis of cancer incidence structure in the Republic of Uzbekistan. Oнкoлoгия И Paдиoлoгия Kaзaxcтaнa 2021, 61, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Information Center of Korea. Available online: https://Cancer.go.kr (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Ob-servatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IARC; WHO. GLOBOCAN 2020, Cancer Today-Estimated Number of Death in 2020, Global Cancer Observatory. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Cancer Uzbekistan 2020 Country Profile. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cancer-uzb-2020 (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- WHO. Cancer Republic of Korea 2020 Country Profile. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cancer-kor-2020 (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- IAEAI; WHO. Cancer Control Capacity and Needs Assessment Report (imPACT Review Report); Ministry of Health and Population: Ramshah Path, Kathmandu, 2022.

- Boyle, P.; Levin, B. International Agency for Research on Cancer. In World Cancer Report 2008; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Health Observatory; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/database/en/ (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Yalaza, M.; İnan, A.; Bozer, M. Male breast cancer. J. Breast Health 2016, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, B.A.; Sherman, R.L.; Howlader, N.; Jemal, A.; Ryerson, A.B.; Henry, K.A.; Boscoe, F.P.; Cronin, K.A.; Lake, A.; Noone, A.M.; et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2011, Featuring Incidence of Breast Cancer Subtypes by Race/Ethnicity, Poverty, and State. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskaran, S.P.; Huang, T.; Rajendran, B.K.; Guo, M.; Luo, J.; Qin, Z.; Zhao, B.; Chian, J.; Li, S.; Wang, S.M. Ethnic-specific BRCA1/2 variation within Asia population: Evidence from over 78,000 cancer and 40,000 non-cancer cases of Indian, Chinese, Korean and Japanese populations. J. Med. Genet. 2021, 58, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2019 Breast Cancer White Paper Summary. Available online: http://webzine.kbcs.or.kr/rang_board/list.html?num=124&code=news (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Kang, S.Y.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, Z.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.; Bae, S.Y.; Yoon, K.; Lee, S.K.; et al. Breast Cancer Statistics in Korea, 2018. J. Breast Cancer 2021, 24, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jørgensen, K.J. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD001877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalager, M.; Haldorsen, T.; Bretthauer, M.; Hoff, G.; Thoresen, S.O.; Adami, H.O. Improved breast cancer survival following introduction of an organized mammography screening program among both screened and unscreened women: A population-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2009, 11, R44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.B.; Baines, C.J. The role of clinical breast examination and breast self-examination. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashidi, A.; Rajaram, S.S. Middle Eastern Asian Islamic women and breast self-examination: Needs assessment. Cancer Nurs. 2000, 23, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azaiza, F.; Cohen, M. Between traditional and modern perceptions of breast and cervical cancer screenings: A qualitative study of Arab women in Israel. Psycho-Oncology 2008, 17, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudet, M.M.; Gapstur, S.M.; Sun, J.; Diver, W.R.; Hannan, L.M.; Thun, M.J. Active Smoking and Breast Cancer Risk: Original Cohort Data and Meta-Analysis. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Washbrook, E. Risk factors and epidemiology of breast cancer. Women’s Health Med. 2006, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Tobacco Control Fact Sheet 2017. Uzbekistan. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/337447/Tobacco-Control-Fact-Sheet-Uzbekistan.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.; Huang, W.; Lan, H.; Jiang, H. Association between breastfeeding and breast cancer risk: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Breastfeed. Med. 2015, 10, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective; AICR: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Waks, A.G.; Winer, E.P. Breast cancer treatment: A review. JAMA 2019, 321, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradishar, W.J.; Moran, M.S.; Abraham, J.; Aft, R.; Agnese, D.; Allison, K.H.; Blair, S.L.; Burstein, H.J.; Dang, C.; Elias, A.D.; et al. NCCN guidelines® insights: Breast cancer, version 4.2021: Featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ziftawi, N.H.; Shafie, A.A.; Mohamed Ibrahim, M.I. Cost-effectiveness analyses of breast cancer medications use in developing countries: A systematic review. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2021, 21, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatyeva, V.; Derkach, E.V.; Avxentyeva, M.; Omelyanovskiy, V. The Economic Burden of Breast Cancer in Russia. Value Health 2017, 20, A428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrami, R.; Taghipour, A.; Ebrahimipour, H. Personal and socio-cultural barriers to cervical cancer screening in Iran, patient and provider perceptions: A qualitative study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 3729–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Djanklich, S.; Tillyshaykhov, M.; Zakhirova, N.; Berkinov, A. EPV150/#195 Dynamics of the incidence rates for gynecologic cancer in Uzbekistan. BMJ Spec. J. 2021, 31, A89. [Google Scholar]

- Seol, H.-J.; Ki, K.-D.; Lee, J.-M. Epidemiologic characteristics of cervical cancer in Korean women. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 25, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aggarwal, P. Cervical cancer: Can it be prevented? World J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 5, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICO/IARC. Uzbekistan, Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers, Fact Sheet 2021. Available online: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/UZB_FS.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Walboomers, J.M.; Jacobs, M.V.; Manos, M.M.; Bosch, F.X.; Kummer, J.A.; Shah, K.V.; Snijders, P.J.; Peto, J.; Meijer, C.J.; Muñoz, N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 1999, 189, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Human Pappiloma Virus. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/about-hpv.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fhpv%2Fparents%2Fwhatishpv.html (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Di Saia, P.J.; Creasman, W.T. Invasive cervical cancer. In Clinical Gynecologic Oncology, 7th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Braaten, K.P.; Laufer, M.R. Human Papillomavirus (HPV), HPV-Related Disease, and the HPV Vaccine. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 1, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen, M.; Paavonen, J.; Wheeler, C.M.; Jaisamrarn, U.; Garland, S.M.; Castellsagué, X.; Skinner, S.R.; Apter, D.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; et al. Overall efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against grade 3 or greater cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joura, E.A.; Giuliano, A.R.; Iversen, O.-E.; Bouchard, C.; Mao, C.; Mehlsen, E.D., Jr.; Ngan, Y.; Petersen, L.K.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.; Pitisuttithum, P.; et al. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group FIS. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1915–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, S.M.; Hernandez-Avila, M.; Wheeler, C.M.; Perez, G.; Harper, D.M.; Leodolter, S.; Tang, G.W.; Ferris, D.G.; Steben, M.; Bryan, J.; et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1928–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety Statement on the Continued Safety of HPV Vaccination. 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/committee/topics/hpv/GACVS_Statement_HPV_12_Mar_2014.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2014).

- Min, K.-J.; Lee, Y.J.; Suh, M.; Yoo, C.W.; Lim, M.C.; Choi, J.; Ki, M.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.H.; et al. The Korean guideline for cervical cancer screening. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 58, 398–407. [Google Scholar]

- Siebers, A.G.; Klinkhamer, P.J.; Grefte, J.M.; Massuger, L.F.; Vedder, J.E.; Beijers-Broos, A.; Bulten, J.; Arbyn, M. Comparison of liquid-based cytology with conventional cytology for detection of cervical cancer precursors: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronco, G.; Cuzick, J.; Pierotti, P.; Cariaggi, M.P.; Dalla Palma, P.; Naldoni, C.; Ghiringhello, B.; Giorgi-Rossi, P.; Minucci, D.; Parisio, F.; et al. Accuracy of liquid based versus conventional cytology: Overall results of new technologies for cervical cancer screening: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007, 335, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronco, G.; Giorgi-Rossi, P.; Carozzi, F.; Confortini, M.; Dalla Palma, P.; Del Mistro, A.; Gillio-Tos, A.; Minucci, D.; Naldoni, C.; Rizzolo, R.; et al. Results at recruitment from a randomized controlled trial comparing human papillomavirus testing alone with conventional cytology as the primary cervical cancer screening test. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schiffman, M.; de Sanjose, S. False Positive Cervical HPV Screening Test Results; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 184–187. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, B.R. Feasibility evaluation of the overall current national health screening program and suggestions for system improvement. In Academic Research Service Project Research Project 2012-01; Seoul National University College of Medicine: Seoul, Korea, 2013; (현행 국가건강검진 프로그램 전반에 대한 타당성 평가 및 제도개선 방안 제시. 학술연구용역사업연구과제 2012-01. 서울대학교 의과대학). 2013 . [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, A.; Stein, K.; Bryant, T.N.; Breen, C.; Old, P. Relation between the incidence of invasive cervical cancer and the screening interval: Is a five year interval too long? J. Med. Screen. 1996, 3, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sankaranarayanan, R.; Esmy, P.O.; Rajkumar, R.; Muwonge, R.; Swaminathan, R.; Shanthakumari, S.; Fayette, J.M.; Cherian, J. Effect of visual screening on cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Tamil Nadu, India: A cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoni, F.; Maneo, A.; Colombo, A.; Placa, F.; Milani, R.; Perego, P.; Favini, G.; Ferri, L.; Mangioni, C. Randomised study of radical surgery versus radiotherapy for stage Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Lancet 1997, 350, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN Guidelines, Version 1.2022. Cervical Cancer. Available online: http://nccn.org (accessed on 3 May 2022).

| Uzbekistan | South Korea | South-Central Asia | Sub-Saharan African Regions | East Asia | Western Europe | Northern America | Australia and New Zealand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 108.1 | 242.7 | 102.5 | 111.1–130.2 | 217.2 | 325 | 360.7 | 447.6 |

| Mortality | 72.4 | 75.5 | 67 | 78.4–90.1 | 123.2 | 103.3 | 87.1 | 85.8 |

| Incidence per mortality | 67.0% | 31.1% | 65.4% | 69.2–70.6% | 56.7% | 31.8% | 24.1% | 19.2% |

| Uzbekistan | South Korea | South-Central Asia | Sub-Saharan African Regions | Eastern Asia | Western Europe | Northern America | Australia and New Zealand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 26.4 | 64.2 | 26 | 32.7–39.5 | 43.3 | 90.7 | 89.4 | 95.5 |

| Mortality | 12.8 | 6.4 | 13 | 10.4–18 | 9.8 | 15.6 | 12.5 | 12.1 |

| Incidence per mortality | 48.5% | 10.0% | 50.0% | 31.8–45.6% | 22.6% | 17.2% | 14.0% | 12.7% |

| Uzbekistan | South Korea | South-Central Asia | Sub-Saharan African Regions | Eastern Asia | Western Europe | Northern America | Australia and New Zealand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 11 | 8.1 | 15.3 | 22.9–40.1 | 10.8 | 7 | 6.1 | 5.6 |

| Mortality | 6.7 | 1.8 | 9.6 | 16.6–28.6 | 4.9 | 2 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| Incidence per mortality | 60.9% | 22.2% | 62.7% | 71.3–72.5% | 45.4% | 28.6% | 34.4% | 28.6% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rim, C.H.; Lee, W.J.; Musaev, B.; Volichevich, T.Y.; Pazlitdinovich, Z.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Nigmatovich, T.M.; Rim, J.S., on behalf of the Consortium of Republican Specialized Scientific Practical-Medical Center of Oncology and Radiology and South Korean Oncology Advisory Group. Comparison of Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer in Uzbekistan and Korea: The First Report of The Uzbekistan–Korea Oncology Consortium. Medicina 2022, 58, 1428. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58101428

Rim CH, Lee WJ, Musaev B, Volichevich TY, Pazlitdinovich ZY, Lee HY, Nigmatovich TM, Rim JS on behalf of the Consortium of Republican Specialized Scientific Practical-Medical Center of Oncology and Radiology and South Korean Oncology Advisory Group. Comparison of Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer in Uzbekistan and Korea: The First Report of The Uzbekistan–Korea Oncology Consortium. Medicina. 2022; 58(10):1428. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58101428

Chicago/Turabian StyleRim, Chai Hong, Won Jae Lee, Bekhzood Musaev, Ten Yakov Volichevich, Ziyayev Yakhyo Pazlitdinovich, Hye Yoon Lee, Tillysshaykhov Mirzagaleb Nigmatovich, and Jae Suk Rim on behalf of the Consortium of Republican Specialized Scientific Practical-Medical Center of Oncology and Radiology and South Korean Oncology Advisory Group. 2022. "Comparison of Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer in Uzbekistan and Korea: The First Report of The Uzbekistan–Korea Oncology Consortium" Medicina 58, no. 10: 1428. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58101428

APA StyleRim, C. H., Lee, W. J., Musaev, B., Volichevich, T. Y., Pazlitdinovich, Z. Y., Lee, H. Y., Nigmatovich, T. M., & Rim, J. S., on behalf of the Consortium of Republican Specialized Scientific Practical-Medical Center of Oncology and Radiology and South Korean Oncology Advisory Group. (2022). Comparison of Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer in Uzbekistan and Korea: The First Report of The Uzbekistan–Korea Oncology Consortium. Medicina, 58(10), 1428. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58101428