Klatskin Tumor: A Survival Analysis According to Tumor Characteristics and Inflammatory Ratios

Abstract

:1. Introduction

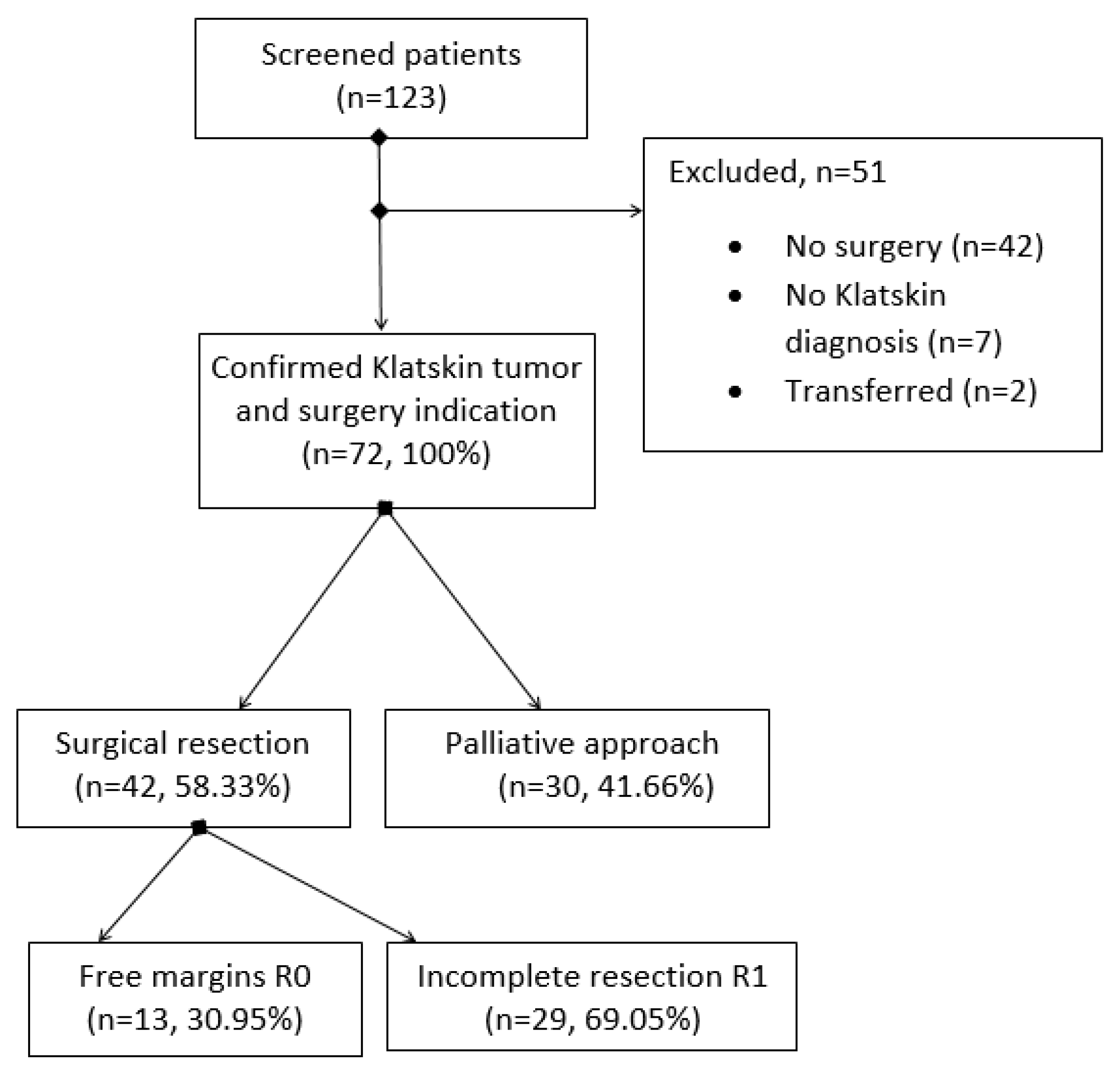

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables, Data Collection, and Follow-Up

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Statement

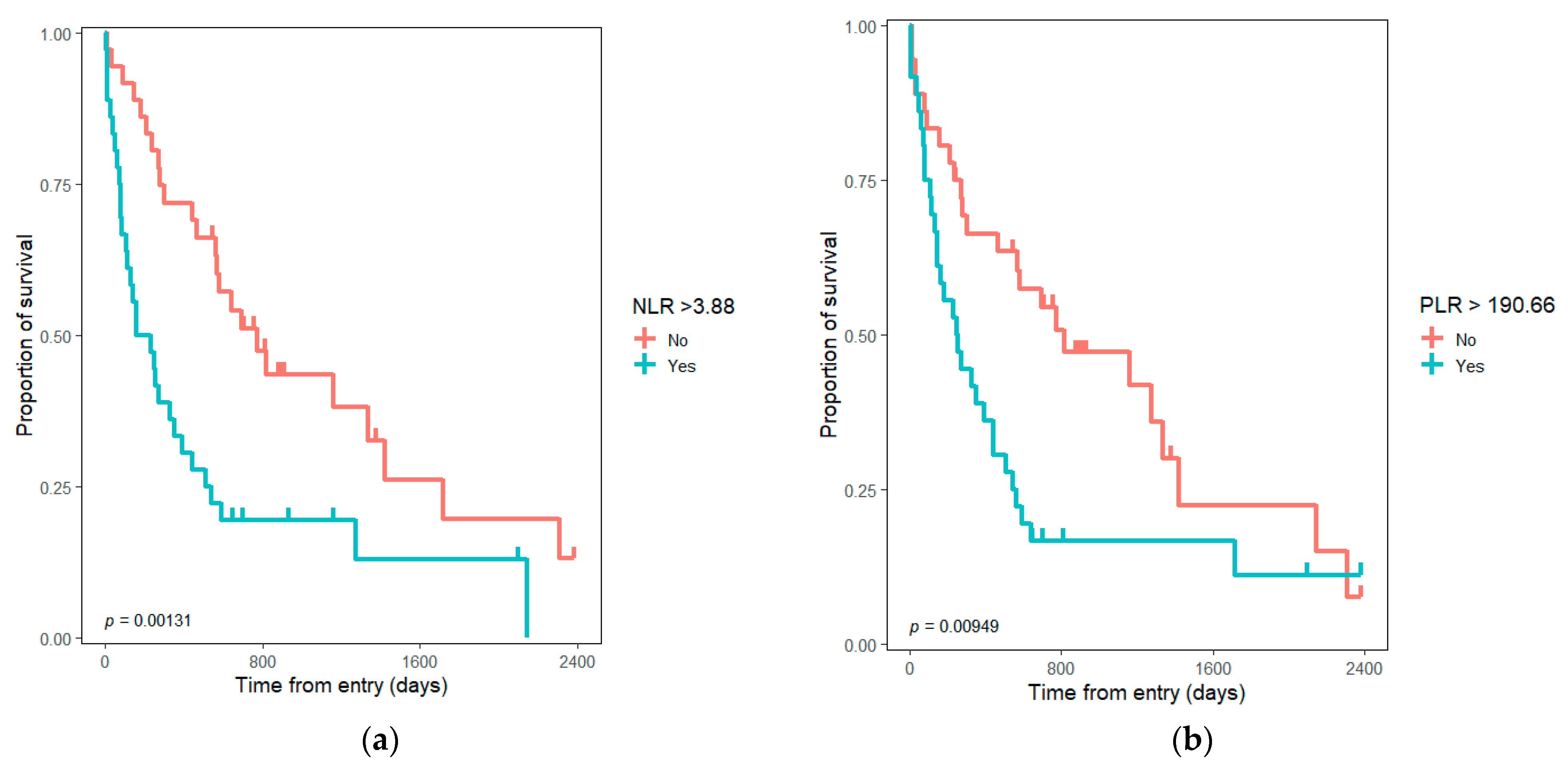

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, P.; Yadav, S. Demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment, and survival of patients with Klatskin tumors. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2018, 31, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blechacz, B.R.; Gores, G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma. Clin. Liver Dis. 2008, 12, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, T.; Park, S.-J.; Han, S.-S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.D.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, S.-A.; Woo, S.M.; Lee, W.J.; Hong, E.K. Proximal Resection Margins: More Prognostic than Distal Resection Margins in Patients Undergoing Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma Resection. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 50, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Klatskin Tumor: A Population-Based Study of Incidence and Survival. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 25, 4503–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarnagin, W.R.; Fong, Y.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Gonen, M.; Burke, E.C.; Bodniewicz, B.J.; Youssef, B.M.; Klimstra, D.; Blumgart, L.H. Staging, Resectability, and Outcome in 225 Patients With Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. 2001, 234, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, A.; Androck, S.; Stangl, J.S.M.; Neu, B.; Born, P.; Classen, M.; Rosch, T.; Schmid, R.M.; Prinz, C. Long-term outcome and prognostic factors of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 1422–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ruys, A.T.; Van Haelst, S.; Busch, O.R.; Rauws, E.A.; Gouma, D.J.; Van Gulik, T.M. Long-term Survival in Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma also Possible in Unresectable Patients. World J. Surg. 2012, 36, 2179–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beckurts, K.T.E.; Hölscher, A.H.; Bauer, T.H.; Siewert, J.R. Maligne Tumoren der Hepaticusgabel—Ergebnisse der chirurgischen Therapie und Prognosefaktoren. Der Chir. 1997, 68, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumanto, Y.H.; Dam, W.A.; Hospers, G.A.; Meijer, C.; Mulder, N.H. Platelets and Granulocytes, in Particular the Neutrophils, Form Important Compartments for Circulating Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Angiogenesis 2003, 6, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagni, F.; Ferroni, P.; Palmirotta, R.; Portarena, I.; Formica, V.; Roselli, M. Review. TNF/VEGF cross-talk in chronic inflammation-related cancer initiation and progression: An early target in anticancer therapeutic strategy. Vivo 2007, 21, 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Scapini, P.; Calzetti, F.; Cassatella, M.A. On the detection of neutrophil-derived vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). J. Immunol. Methods 1999, 232, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.-W.; Fu, Y.; Su, Q.; Guan, M.-J.; Kong, P.; Wang, S.-Q.; Wang, H.-L. Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio in Oncologic Outcomes of Cholangiocarcinoma: A Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kabarriti, R.; Zhang, Y.; Savage, T.; Baliga, S.; Brodin, P.; Kalnicki, S.; Garg, M.K.; Guha, C. NLR as a prognostic factor in solid tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018, 102, e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, S.; Cook, E.; Goulder, F.; Justin, T.; Keeling, N. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2005, 91, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciocan, A.; Bolboacă, S.D.; Drugan, C.; Ciocan, R.A.; Graur, F.; AL Hajjar, N. The Pattern of Calculated Inflammation Ratios as Prognostic Values in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2021, 24, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, D.; Farid, S.; Malik, H.Z.; Young, A.L.; Toogood, G.; Lodge, J.P.A.; Prasad, K.R. Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Prognostic Predictor after Curative Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. World J. Surg. 2008, 32, 1757–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, K.M.; Belcher, E.; Raevsky, E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Goldstraw, P.; Lim, E. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and its association with survival after complete resection in non–small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009, 137, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Y.-T.; Jiang, J.-H.; Yang, H.-J.; Wu, Z.-J.; Xiao, Z.-M.; Xiang, B.-D. The lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio is a superior predictor of overall survival compared to established biomarkers in HCC patients undergoing liver resection. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toda, M.; Tsukioka, T.; Izumi, N.; Komatsu, H.; Okada, S.; Hara, K.; Miyamoto, H.; Ito, R.; Shibata, T.; Nishiyama, N. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with surgery and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Thorac. Cancer 2017, 9, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rossi, S.; Basso, M.; Strippoli, A.; Schinzari, G.; D’Argento, E.; Larocca, M.; Cassano, A.; Barone, C. Are Markers of Systemic Inflammation Good Prognostic Indicators in Colorectal Cancer? Clin. Color. Cancer 2017, 16, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Lee, J.H.; Hwang, D.W.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, K.-M.; Lee, Y.-J. The Proximal Margin of Resected Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: The Effect of Microscopic Positive Margin on Long-Term Survival. Am. Surg. 2012, 78, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matull, W.-R.; Dhar, D.K.; Ayaru, L.; Sandanayake, N.S.; Chapman, M.H.; Dias, A.; Bridgewater, J.; Webster, G.J.M.; Bong, J.J.; Davidson, B.R.; et al. R0 but not R1/R2 resection is associated with better survival than palliative photodynamic therapy in biliary tract cancer. Liver Int. 2010, 31, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seyama, Y.; Kubota, K.; Sano, K.; Noie, T.; Takayama, T.; Kosuge, T.; Makuuchi, M. Long-Term Outcome of Extended Hemihepatectomy for Hilar Bile Duct Cancer With No Mortality and High Survival Rate. Ann. Surg. 2003, 238, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, G.; Hoppe-Lotichius, M.; Bittinger, F.; Schuchmann, M.; Düber, C. Klatskin Tumour: Meticulous Preoperative Work-Up and Resection Rate. Z. Für Gastroenterol. 2011, 49, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillemoe, K.D. Klatskin Tumors. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6906/ (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Stavrou, G.; Donati, M.; Faiss, S.; Jenner, R.M.; Niehaus, K.; Oldhafer, K. Zentrales Gallengangskarzinom (Klatskin-Tumor). Der Chir. 2014, 85, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, K.; Vasiliadis, K.; Kalpakidis, V.; Christoforidis, E.; Avgerinos, A.; Botsios, D.; Megalopoulos, A.; Haidich, A.B.; Betsis, D. A single-center experience in the management of Altemeier-Klatskin tumors. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2007, 16, 383–389. [Google Scholar]

- Kitano, Y.; Yamashita, Y.-I.; Yamamura, K.; Arima, K.; Kaida, T.; Miyata, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Mima, K.; Imai, K.; Hashimoto, D.; et al. Effects of Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratios on Survival in Patients with Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 3229–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.J.; Jang, J.-Y.; Chang, J.; Shin, Y.C.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, S.-W. Actual Long-Term Survival Outcome of 403 Consecutive Patients with Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma. World J. Surg. 2016, 40, 2451–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F. Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma (Staging). Reference Article. Available online: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/perihilar-cholangiocarcinoma-staging?lang=us (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Hau, H.-M.; Meyer, F.; Jahn, N.; Rademacher, S.; Sucher, R.; Seehofer, D. Prognostic Relevance of the Eighth Edition of TNM Classification for Resected Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, D.J.; Gwon, D.I.; Han, K.; Kim, Y.; Ko, G.-Y.; Shin, J.H.; Ko, H.K.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.W.; Yoon, H.-K.; et al. Percutaneous Metallic Stent Placement for Palliative Management of Malignant Biliary Hilar Obstruction. Korean J. Radiol. 2018, 19, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romania Population (2022)—Worldometer. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/romania-population/ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Nechita, V.I.; Bolboacă, S.D.; Graur, F.; Moiş, E.; Al-Hajjar, N. Evaluation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte, platelet-to-lymphocyte, and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratios in patients with Klatskin tumors. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2021, 92, 162–171. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Lachapelle, J.; Leung, S.; Gao, D.; Foulkes, W.D.; Nielsen, T.O. CD8+ lymphocyte infiltration is an independent favorable prognostic indicator in basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, W.J.; Cleghorn, M.C.; Jiang, H.; Jackson, T.; Okrainec, A.; Quereshy, F.A. Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio is a Better Prognostic Serum Biomarker than Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients Undergoing Resection for Nonmetastatic Colorectal Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Yoo, H.M.; Park, C.H.; Song, K.Y. The Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Versus Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio: Which is Better as a Prognostic Factor in Gastric Cancer? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 4363–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, S.-M.; Yang, H.; Yang, L.-X.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.-D.; Yin, D.; Shi, Y.-H.; Cao, Y.; Dai, Z.; et al. Systemic inflammation score predicts survival in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma undergoing curative resection. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, G.; Liu, Q.; Ma, J.-Y.; Liu, C.-Y. Prognostic Significance of Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Cholangiocarcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7375169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H.; Wan, X.; Bai, Y.; Bian, J.; Xiong, J.; Xu, Y.; Sang, X.; Zhao, H. Preoperative neutrophil–lymphocyte and platelet–lymphocyte ratios as independent predictors of T stages in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 5157–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, H.-J.; Jin, Y.-W.; Zhou, R.-X.; Ma, W.-J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.-K.; Liu, F.; Cheng, N.-S.; Li, F.-Y. Clinical Value of Inflammation-Based Prognostic Scores to Predict the Resectability of Hyperbilirubinemia Patients with Potentially Resectable Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2018, 23, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Lu, W.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Dong, J. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in biliary tract cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36857–36868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okuno, M.; Ebata, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Igami, T.; Sugawara, G.; Mizuno, T.; Yamaguchi, J.; Nagino, M. Appraisal of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with unresectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2016, 23, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All Subjects (n = 72) | Tumor Resection (n = 42) | Unresectable Cases (n = 30) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) a | 64.91 ± 9.15 | 65.54 ± 8.87 | 64.03 ± 9.62 |

| Male gender b | 47 (65.27%) | 28 (66.66%) | 19 (63.33%) |

| Urban setting b | 39 (54.16%) | 26 (61.90%) | 13 (43.33%) |

| Bismuth class b | |||

| I | 16 (22.22%) | 9 (21.42%) | 7 (23.33%) |

| II | 10 (13.88%) | 7 (16.66%) | 3 (10%) |

| III | 25 (34.72%) | 17 (40.47%) | 8 (26.66%) |

| IV | 21 (29.16%) | 9 (21.42%) | 12 (40%) |

| Tumor stage (T) b | |||

| I | 7 (9.72%) | 7 (16.6%) | na |

| II | 24 (33.33%) | 24 (57.14%) | na |

| III | 11 (15.27%) | 8 (19.04%) | 3 (10%) |

| IV | 30 (41.66%) | 3 (7.14%) | 27 (90%) |

| Node stage (N) c | |||

| 0 | 28 (66.66%) | 28 (66.66%) | na |

| 1 (1–3 regional lymph nodes) | 13 (31.66%) | 13 (30.95%) | na |

| 2 (≥4 regional lymph nodes) | 1 (2.38%) | 1 (2.38%) | na |

| Metastasis (M) b | 12 (16.66%) | 0 | 12 (40%) |

| TNM d | |||

| I | 7/54 (12.96%) | 7/42 (16.66%) | na |

| II | 16/54 (29.62%) | 16/42 (38.09%) | na |

| III | 18/54 (33.33%) | 18/42 (42.85%) | na |

| IV | 13/54 (24.072%) | 1/42 (2.38%) | na |

| Event (death) b | 55 (76.38%) | 26 (61.9%) | 26 (86.66%) |

| Negative resection margin (R0) b | 13 (18.05%) | 13 (30.95%) | na |

| Median survival time (days) | 442 (273–641) | 774 (563–1716) | 147 (91–301) |

| NLR at admission | 3.88 (2.86–5.18) | 3.26 (2.56–4.19) | 4.84 (3.92–7.10) |

| PLR at admission | 190.66 (133.15–317.68) | 152.52 (124.81–249.96) | 238.15 (182.92–352.21) |

| LMR at admission | 2.96 (1.91–4.18) | 3.48 (2.52–4.38) | 1.92 (1.5–3.03) |

| SII at admission | 1118.11 (717.94–1973.42) | 850.55 (579.75–1331.35) | 1673.64 (927.21–2489.5) |

| WBC at admission (103/μL) | 8.49 (6.84–10.67) | 7.82 (6.03–9.93) | 8.9 (7.41–11.66) |

| CRP at admission (mg/dL) | 0.62 (0.4–2.44) | 0.64 (0.39–2.9) | 0.57 (0.44–1.55) |

| NLR > median | 36 (50%) | 13 (30.95%) | 23 (76.66%) |

| PLR > median | 35 (50%) | 14 (33.33%) | 22 (73.33%) |

| LMR > median | 35 (50%) | 27 (64.28%) | 9 (30%) |

| SII > median | 35 (50%) | 15(35.71%) | 21 (70%) |

| NLR > 3 | 51 (70.83) | 25 (59.52%) | 26 (86.66%) |

| NLR > 6 | 13 (18.05%) | 3 (7.14%) | 10 (33.33%) |

| PLR > 150 | 48 (66.66%) | 23 (54.76%) | 25 (83.33%) |

| PLR > 200 | 35 (48.61%) | 14 (33.33%) | 21 (70%) |

| LMR > 3 | 36 (50%) | 27 (64.28%) | 9 (30%) |

| HR Unadjusted | (95% CI) | p | HR Adjusted * | (95% CI) | p | HR Adjusted # | (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR | 1.13 | (1.07–1.19) | <0.001 | 1.09 | (1.02–1.15) | 0.0057 | 1.07 | (0.8032–1.427) | 0.6422 |

| PLR | 1.004 | (1.002–1.006) | <0.001 | 1.003 | (1.001–1.005) | 0.0017 | 1.002 | (0.9981–1.007) | 0.2726 |

| LMR | 0.84 | (0.69–1.014) | 0.069 | 0.9 | (0.75–1.09) | 0.31 | 1.26 | (0.9945–1.609) | 0.0555 |

| SII | 1.0003 | (1.0002–1.0004) | <0.001 | 1.0002 | (1.0001–1.0003) | 0.0037 | 1.000 | (0.9998–1.001) | 0.1577 |

| NLR ≥ median | 2.39 | (1.38–4.13) | 0.0018 | 2.01 | (1.06–3.83) | 0.03 | 1.05 | (0.4410–2.480) | 0.9189 |

| PLR ≥ median | 2.02 | (1.18–3.48) | 0.0109 | 1.33 | (0.73–2.4) | 0.35 | 0.89 | (0.3518–2.245) | 0.8029 |

| LMR ≥ median | 0.54 | (0.32–0.92) | 0.024 | 0.7 | (0.39–1.26) | 0.24 | 1.79 | (0.7201–4.434) | 0.2107 |

| SII ≥ median | 2.29 | (1.31–4.02) | 0.004 | 1.64 | (0.88–3.02) | 0.12 | 1.22 | (0.5012–2.953) | 0.6648 |

| NLR ≥ 3 (Yes vs. No) | 1.8 | (0.97–3.32) | 0.0587 | 1.82 | (0.94–3.55) | 0.08 | 0.73 | (0.3334–1.590) | 0.4261 |

| NLR ≥ 6 (Yes vs. No) | 3.45 | (1.81–6.58) | <0.001 | 2.85 | (1.426–5.68) | 0.003 | 2.19 | (0.5081–9.478) | 0.2924 |

| PLR ≥ 150 (Yes vs. No) | 1.98 | (1.09–3.57) | 0.024 | 1.54 | (0.82–2.89) | 0.17 | 0.79 | (0.3208–1.980) | 0.6250 |

| PLR ≥ 200 (Yes vs. No) | 1.89 | (1.11–3.26) | 0.02 | 1.238 | (0.68–2.23) | 0.49 | 0.89 | (0.3518–2.245) | 0.8029 |

| LMR ≥ 3 (Yes vs. No) | 0.53 | (0.32–0.92) | 0.024 | 0.71 | (0.39–1.26) | 0.24 | 1.79 | (0.7201–4.434) | 0.2107 |

| SII ≥ 1200 (Yes vs. No) | 2.1 | (1.21–3.65) | 0.007 | 1.73 | (0.93–3.23) | 0.08 | 0.96 | (0.39–2.34) | 0.93 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nechita, V.-I.; Moiş, E.; Furcea, L.; Nechita, M.-A.; Graur, F. Klatskin Tumor: A Survival Analysis According to Tumor Characteristics and Inflammatory Ratios. Medicina 2022, 58, 1788. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58121788

Nechita V-I, Moiş E, Furcea L, Nechita M-A, Graur F. Klatskin Tumor: A Survival Analysis According to Tumor Characteristics and Inflammatory Ratios. Medicina. 2022; 58(12):1788. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58121788

Chicago/Turabian StyleNechita, Vlad-Ionuţ, Emil Moiş, Luminiţa Furcea, Mihaela-Ancuţa Nechita, and Florin Graur. 2022. "Klatskin Tumor: A Survival Analysis According to Tumor Characteristics and Inflammatory Ratios" Medicina 58, no. 12: 1788. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58121788